Emotional Reactions and Burnout of Instructors Teaching Wards with Exceptional Needs in Inclusive Schools in Offinso Municipality: Moderating Roles of Coping Mechanisms ()

1. Introduction

Inclusion is giving education to children with disabilities and special educational needs in regular schools. Inclusion is the most effective means of doing away with discrimination, creating welcoming communities, building an inclusive society and achieving education for all. Social justice is a central ingredient of inclusion since it opposes segregation. In addition, social justice is centered on the ideas of challenging the arrangements that promote the continuation of marginalization and exclusionary practices; and it supports a foundational process of respect, care, recognition, and empathy.

By this, all children including those with special educational needs are to be educated in the regular school where equal opportunities and access are to be assured. Children can only be educated in a special school when their needs cannot be provided in a regular school. Thus, all countries are encouraged including Ghana to support the ideology and formulate SEN policies to regulate its development and practice. The demand for inclusion has its roots in the campaigns for access to education and human rights for all. It is driven by the belief that all forms of segregation are morally wrong and are educationally inefficient. Those supporting this view like Stainback and Stainback (1992) have argued that it is necessary to avoid the negative effects of segregation and point out that separate is not equal. Mittler (2012) opines that the main argument driving the inclusion agenda has centered on the issue of human rights. He argues that it is a basic right for pupils to attend their mainstream school and test children. This suggests that segregation means treating children in a way which does not recognize their equality and dignity. According to a UN General comment published in 2001, explained that discrimination on the basis of disability offends human dignity of the child. Tilstone, Frorian and Rose (2002) emphasize that a growing sense of injustice about the idea of segregated special schooling for children with special educational needs has led to calls for more inclusive education opportunities as a right and equal opportunity.

Additionally, human rights perspective, which recognizes the rights of all students to inclusion, the existence of segregated special schools is a form of institutional discrimination. The human rights advocates therefore contend that, students’ rights to inclusive education are universal. Shakespeare (1994) agreed that no child should be denied inclusion in mainstream provision. Mainstream provision should offer the full range of support and specialist services necessary to give all children their full entitlement to a broad and balanced education. This statement has reaffirmed the burning desire and intentions of governments all over the world to fight for equal rights for all categories of children in terms of their education.

There is a disparity between the academic practices that Colleges of Education and Universities teach their students and the experiences students actually encounter as beginning teachers (Darling-Hamond, 2010) . Wasserman (2007) confirms that her college teacher training did not prepare her for the realities of the overwhelming and exhausting human interactions and dilemmas that make up life in the classrooms. All learners, regardless of their intrinsic abilities, are entitled to be educated as it is an essential human right and are deserving of receiving it. However, studies have revealed that the majority of wards in underdeveloped nations who have exceptional needs do not attend school because of the socio-cultural beliefs and practices that exist in those countries (Gyimah, 2006; Ozoji, 2020) . Because of this, education which is inclusive has gained support in the majority of nations in recent years. According to Lamture and Gathoo (2017) , equity and equality in education are critical components of today’s educational system. A movement in educational philosophy has also been influenced by equity and equality, which has led to the development of several different models, such as segregated, integrated, and inclusive education. The trend toward including wards who have special requirements in conventional classroom settings is becoming increasingly common around the world. Education is a fundamental right, and all wards, regardless of their innate aptitude, are deserving of receiving it. However, studies have revealed that the majority of wards in underdeveloped nations who have exceptional needs do not attend school because of the socio-cultural beliefs and practises that exist in those countries (Gyimah, 2006; Ozoji, 2020) . Because of this, education that is inclusive has gained support in the majority of nations in recent years. According to Lamture and Gathoo (2017) , equity and equality in education are critical components of today’s educational system. A movement in educational philosophy has also been influenced by equity and equality, which has led to the development of several different models, such as segregated, integrated, and inclusive education. The trend toward including wards who have special requirements in conventional classroom settings is becoming increasingly common around the world.

Per Ainscow (2011) , the bulk of education institutions all over the globe have made it one of their top priorities to ensure that students who have special needs are welcomed and included in public schools. This is the case not just in the United States but also everywhere in the world. As a result, the issue of academic inclusion is at the forefront of the conversation over educational policy in a plethora of varied nations. A touchier question is whether districts have been trying hard enough to meet special education students’ needs and fulfill their obligations under federal law during the pandemic (Zhang et al., 2008) . As a result, the inclusion of wards who have exceptional needs in conventional classroom settings is a core tenet of the universal concept of education for everyone or all. The fundamental right to be educated for all people, in addition to the rights to non-discrimination and participation, serves as the conceptual anchor for the inclusive education approach (Nolan, Schultz, Cialdini, Goldstein, & Griskevicius, 2011) . The significance of universal schooling is generally understood, and its advancement is advocated for not just by a select group of passionate folks and agencies, but also by organisations affiliated with the United Nations and state authorities.

Standards and binding arbitration clauses such as the 2006 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), that also was the initial global lawfully binding tool to explicitly inspire inclusive schooling as a right, have been of tremendous assistance in accomplishing the overall aim of inclusive schooling and placing it much nearer to becoming a real thing. This present document was made possible because to the foundation that was created by the World Programme of Action (1982), the Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action (1994) and the Standard Rules on Equalisation of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities (1993). This framework incorporates some of the most important tenets of inclusion, such as the idea that wards have a diverse set of qualities and requirements. Because of this, schools must accommodate learners despite their academic capacity, physical condition, social standing, or emotional state. Wards who have exceptional needs should be able to attend the schools in their local communities since these schools are better equipped to facilitate their education and recognise the importance of community involvement in the process of inclusion.

Integration has always been a core element of the reform initiative for improvement of the provision of guidelines to wards with special needs by focusing on the position of these learners in regular academic establishments. This movement for reform seeks to enhance the level of education that is made available to learners who have requirements beyond those of typical students. State academic establishments are supposed to offer instruction to all wards with peculiar circumstances in the least restrictive environment that is practical for them, and all wards who have been identified with peculiar problems are entitled to enrol in state academic establishment (UNESCO, 2005) . The government of Ghana recognised the importance of putting into practise a system of inclusive education and began testing out a pilot version of the initiative in the 2003-2004 school year. The program’s primary objectives were to train instructors to work with learners who have special demands in regular institutions or classes and to ensure that education is available to every learner.

Wards who have special educational requirements can participate in inclusive education by going to conventional schools and receiving instruction there, typically under supervision of some educator belonging to a regular institution (Lamture & Gathoo, 2017) . In resource units, each learner has an allocated resource teacher who acts in a supportive role in making sure that exceptional learners have their requirements fulfilled (Mastropieri et al., 2015) . When it comes to accomplishing the objectives of holistic learning in school settings, the contribution of both general and resource instructors is critical.

The advent of inclusion has been one factor that has contributed to the skyrocketing increase in the number of wards enrolling in mainstream educational settings in Ghana. Due to the fact that instructors are the single most significant human resource for the successful delivery of a syllabus, it is quite possible that a teacher may run into substantial challenges when working in inclusive schools to educate learners who have exceptional needs. They are the ones who modify the thoughts and expectations that the designer has and put them into action. The obstacles that need to be overcome in order to improve the instruction style of instructors in instruction modules in Ghana are significant, and there is an undoubted requirement for a trained teaching force for people who have extraordinary requirements. Teaching wards who have exceptional needs in an inclusive setting requires ordinary instructors to display a certain level of professionalism as they go about their work of supporting wards in acquiring the abilities of writing and reading. This is especially true in the context of the classroom. Regular instructors’ responsibilities in inclusive schools now include day-to-day tasks such as meticulous preparation and instruction, as well as the development of comprehensive methods, are what instructors do to help their learners overcome the obstacles that are placed in front of them (Nind & Wearmouth, 2016; Florian, 2013) . In addition, Instructors in standard classrooms are all now obligated to show their subjective responsiveness to the multi-faceted kind of the distinctive specialness of their learners (Bourke, 2011) , in addition to the manner in which they will be able to connect with their learners so that no learner is hurt by their procedures while presenting their tutorials. This is because regular instructors are supposed to understand tools for promoting progressive inclusion (Agbenyega, 2012) . This is to ensure that no learner is left behind (Jordan, Glenn, & McGhie, 2011) .

In addition, it is required of instructors that they increase the amount of assessment testing that they do and the reporting that they do to their supervisor and administrator (Bourke, 2011) . Inclusion requires using teaching that is centred on the child. Wards should be the focus of flexible educational programmes rather than the other way around. In order to cater to the need of wards who have special requirements, inclusive education requires adequate resources and support. They highlight that instructors play an important role by trying to tackle the variety of learners’ priorities and objectives via a huge repertoire of creative teaching and learning tactics that do not marginalise the learners within the context of the larger educational system. Additionally, Opertti and Brady (2011) mention a few additional new responsibilities of inclusive teachers. They point out that teachers play a crucial part in the process by trying to tackle the varied desires and requirements of learners (p. 470).

In order to fulfil the fundamental purpose of their position as educators in inclusive schools, they are required to make full use of peculiar competencies and resources. This is done in order to accommodate the various levels of capability possessed by learners as well as the ever-growing variety of their requirements. They need to dedicate a greater amount of time and money to the cause in order to make sure learners with special needs achieve their educational objectives (Jennett, Harris, & Mesibov, 2013) . In addition to being held accountable for the development and execution of special education programmes and strategies, instructors are required to continually expand their knowledge in areas such as finding answers to queries, interpersonal interaction amongst people, the preparation and development of curricula (Winzer, 2011; Klein, Cook, & Richardson-Gibbs, 2011) . Instructors have also been mandated to develop creative teaching ways or methodologies, join forces with other specialists both within and outside their campuses, and make a prolific output to the architecting of settings that allow learners to excel on campuses. This has been done in order to ensure that learners have the best possible opportunity to learn. This has been done in an effort to improve the educational experience for learners (Stainback, 2012) .

In addition, wards who have special needs face a different set of obstacles than other wards, which has been a factor in the lack of effectiveness of an all-inclusive schooling module. Also, because the number of learners who have exceptional requirements is rising at an exponential rate in today’s classrooms, educators who teach general education are confronted with a wide variety of difficulties when working in inclusive academic establishment (Busby, Ingram, Bowron, Oliver, & Lyons, 2012) . Particularly essential in general education classrooms is providing learners with opportunities to use their imaginations and think in ways that are more creative than taking a literal approach to their work. This presents a challenge for educators who work in environments that are inclusive (Harbinson & Alexander, 2011) . This has the potential to create problems with regard to school syllabus standards. Additionally, instructors require extra help in their classrooms, which, depending on the type of the assistance provided, may be quite beneficial to the learners.

Therefore, educators working in inclusive schools confront a significant challenge when it comes to assisting learners who have exceptional requirements. The significance of both their personalities and their emotional make-up cannot be overstated. Because teaching involves feeling, it is generally accepted that instructors’ natural feelings should be considered an essential component of the classroom environment (Hargreaves, 2011) . There is a correlation between the emotions that are natural to instructors and a number of different outcomes, including the healthiness and wellness of instructors (Chang, 2012; Keller, Chang, Becker, Goetz, & Frenzel, 2014) , the essentiality of the classroom (Sutton, 2013) , the feelings and learners’ drive (Becker, Goetz, Morger, & Ranellucci, 2014; Radel, Sarrazin, Legrain, & Wild, 2010) , as well as their accomplishments in studies (Beilock, Gunderson, Ramirez, & Levine, 2015) .

Per Cherry, Fletcher, O’Sullivan, and Doman (2014) , emotions is a multifaceted mental condition that is comprised of the following three distinct aspects: a subjective sensation, a bodily reaction, and a behavioural or verbal expression. In public education or academic establishments with all kinds of learners such as those with peculiar needs and those without, emotional responses relate to the display of teachers’ sensations, which may be either good or negative. However, it is crucial to highlight that emotions can occur in any circumstance.

Emotions are significant in the classroom because they have an effect that is counterproductive to the learning that takes place for the kids. Learners’ capacities to digest information and meaningfully comprehend what they encounter are impacted by their emotional experiences. For all of these reasons, it is absolutely essential for instructors to form an atmosphere in class which is both physically healthy and emotionally safe for the purpose of maximising the learning potential of their learners, who are wards. However, Gyimah (2006) showed that instructors feel negative emotional reactions when educating wards who have exceptional needs. This was discovered in an investigation that she conducted. In the opinion of Zembylas and Barker (2012) , instructors experience nervousness, unhappiness, indignation, shame, awkwardness, dread, feelings of isolation, and helplessness as a result of their poor experience in having a fruitful conversation with wards who have uncommon necessities. Hence, such sentiments are caused by the instructors’ lack of understanding of how to communicate with wards who have special requirements. These feelings are caused by the fact that instructors have limited knowledge of how to deal with wards who have exceptional needs.

Per Sarıçam and Sakz (2014) , instructors who work with wards who have exceptional needs report higher levels of burnout, and they feel wearier and more depersonalised in their work than instructors who work with learners who are part of the mainstream education system. Burnout can occur in teaching hinged on these feelings being exacerbated by the negative reactions. The terms tiredness, fatigue, and apathy collectively relate to the state of burnout, which can occur as a consequence of extended periods of overwork (Berry, 2011) . Instructors who work with learners who have special requirements have a greater risk of job burnout and are more likely to quit their employment than instructors who work with learners who do not have special requirements (Gersten, Keating, Yovanoff, & Harniss, 2011; Stempien & Loeb, 2002) .

It could be because instructors in inclusive schools are obliged to fill in for so many or plenty jobs and perform a chunk of activities. As per Tsouloupas, Carson, Matthews, Grawitch, and Barber (2011) , burnout is characterised by a decreased sense of personalized success along with feelings of depersonalization and mental and physical tiredness. Burnout is a response that occurs as a result of persistent engagement and can be caused by coping with negative feelings in a way that is both permanent and ineffective.

If an instructor’s anger and frustration and exhaustion are not adequately handled, there is a chance that the instructor’s feeling of self-efficacy would suffer as a result. Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk (2001) provide a definition of the notion of self-efficacy that educators hold as “a teacher’s judgement of his or her capacities to bring about anticipated results of learner engagement and learning, especially among those pupils who may be tough or uninspired”. When a teacher is dealing with wards who have extraordinary needs, unbeneficial sentiments and fatigue can seriously negatively have a bearing on learners’ vim and enthusiasm. This is especially true when the wards have special needs. Not only is an instructor’s personal belief a measure of their performance and how committed they are to their job, but it also has a direct bearing on how resilient and motivated they are (Goddard, Hoy, & Hoy, 2012; Labone, 2014; Wheatley, 2015) .

The degree toward which demographic characteristics like gender, maturity level, and years of teaching encounter impact instructors in mainstream schools can be affected by the instinctive responses, burnout, self-efficacy, and protective factors that those instructors undergo. Per Özokcu (2018) , they have been found to have a substantial relationship to the feelings, exhaustion, and self-efficacy of instructors. Despite the fundamental roles that emotions play in the lives of humans, in the realm of education for instructors, the investigation of feelings has received little attention (Spillane, Reiser, & Reimer, 2012; Zembylas, 2014) . This is in spite of the fact that emotional considerations have been ignored.

Understanding the impact that teaching can have on a person’s emotional state can help us better comprehend the factors that contribute to a sense of emotional depletion in a classroom setting (Day & Leitch, 2001) . A teacher who continues to work in the profession despite being emotionally spent out and having achieved burnout is less effective and also has more unfavourable opinions regarding the job (Gersten, Keating, Yovanoff, & Hamiss, 2011) . The investigation of emotional reactions, weariness, and emotions of self-efficacy has become an important problem as a direct consequence of these unfavourable outcomes.

It is common knowledge that having access to the appropriate resources is essential to ensuring that every stage of development is carried out in an effective and profitable manner (Sunderman, Tracey, Kim, & Orfield, 2014) . Hence, it is essential to emphasise the fact that instructors at all levels, but especially those in elementary and secondary schools, require access to certain resources in order to be able to conduct effective instruction and learning activities with their learners. Because in order for instructors to be able to offer their absolute best, they need to first be able to triumph over the problems that they face, it is vital to provide resources for wards who have unique needs (Wood & McCarty, 2012) .

In a few of these all-embracing institutions, pedagogical aids and specialised pieces of apparatus are all but non-existent (Sunderman, Tracey, Kim, & Orfield, 2014) . As a direct consequence of this, the youngsters may experience a great deal of difficulty in their academic pursuits. According to Gersten, Keating, Yovanoff, and Hamiss (2011) , the academic performance of wards who have unique needs is negatively impacted when the school does not provide adequate amenities such as specialised materials and equipment. As a result of having to solve the challenges, there is a high probability that the educator will get exhausted, suffer from burnout, and have a negative effect on their own feeling of personalised belief as a response. It has been demonstrated once more that the nature of the impairment and the type of disability can also affect the feelings that instructors have toward inclusion (Ryan, 2016) . These circumstances are likely to have an impact on the instructors’ ability to effectively and precisely convey knowledge to their learners, as well as the instructors’ own well-being.

In spite of these factors, it seems that only a limited number of research have been conducted on the emotional responses, burnout, personal belief in one’s self, and adjustment mechanisms of teachers who work in inclusive or embracing academic establishments with learners who have exceptional needs have been carried out in Ghana. For example, Gyimah (2006) discovered that instructors did not react favourably to educating people with severe and profound intellectual disabilities, as well as those who were hard of hearing, deaf, or blind, and as a result, they displayed negative feelings. Nketsia (2016) discovered that while pre-service teachers were happier connecting with wards who had peculiar or distinct requirements, their general sentiments were scarcely favourable, and some of them were inclined to cultural ideas about disability. They discovered that pre-service instructors were more at ease getting involved with wards with distinct needs, despite the fact that pre-service instructors were aware of disability in terms of the complicated interplay between genetic and factors from people’s surrounding. Per these findings, educators working in inclusive schools experience certain emotional issues. Both the investigation by Gyimah (2006) and the investigation by Nketsia (2016) focused solely on the attitudes of instructors who were instructing wards who had exceptional needs. Gyimah’s research was conducted in 2006 and Nketsia’s in 2016. The current investigation, on the other hand, concentrates on in-service teachers in inclusionary institutions, focusing special emphasis to the emotional responses, burnout, self-efficacy, and buffering strategies of these teachers in the context of educating students in inclusive educational institutions who have unique requirements in the Offinso municipality.

1.1. Conceptual Framework

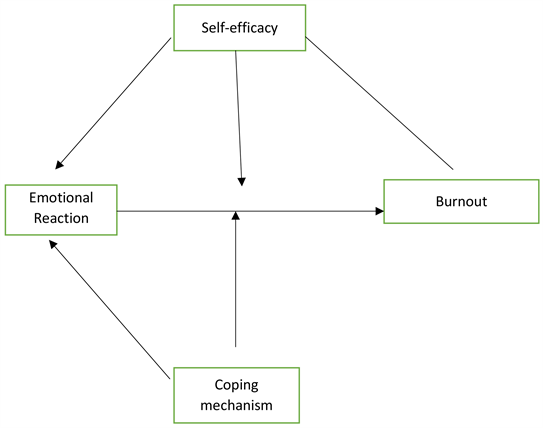

Emotional reaction has a direct impact on academic burnout of teachers teaching students with exceptional needs, notwithstanding teachers’ self-efficacy has influence on teachers’ emotional reaction, again teachers coping mechanism plays a great impact on teachers’ emotional reaction. Both teachers coping mechanism and teacher’s self-efficacy plays a mediating role between teachers’ emotional reaction and teachers’ burnout.

The following research questions and hypotheses were investigated throughout the course of this investigation:

1.2. Research Question

1) Find out instructors in inclusive institutions emotional responsiveness.

2) Ho: Coping mechanisms will not moderate emotional reactions and burnout of instructors.

H1: Coping mechanisms will moderate, emotional reactions and burnout of instructors.

3) Ho: There is no statistically significant link or correlation between instructors coping mechanism and their burnout.

H1: There is a statistically significant link or correlation between instructors coping mechanism and their burnout.

2. Method

The path that the investigation was going to take, as well as its goals, led to the decision to use descriptive survey research. The Offinso Municipality served as the location for the research project. During the course of the inquiry, a descriptive survey design and a cross-sectional investigation technique were utilised. In survey designs, the researcher will give a survey instrument to either a representative sample of the population or to the full population as a whole to get data on the behaviours or characteristics of the population as a whole. Creswell and Clark (2017) Plano’s research was cited. We employed a descriptive survey to perform a thorough investigation of the reactions of sentiments/feelings and burnout experienced by instructors working in inclusive schools in the Offinso municipality. These instructors are responsible for instructing learners who have special needs. This method was helpful in lowering the level of prejudice and providing an objective foundation for choosing (Curtis & Curtis, 2016) . According to the sample size determination table for descriptive research developed by Krejcie and Morgan (1970) , the optimal number of participants for the sample should have been 291 out of a total population of 1155 instructors working in inclusive schools across the three municipalities. In the course of the research, a multi-level sampling approach was utilised as the method of sampling. First, the approach of purposive sampling was utilised so that only inclusive schools within the Offinso municipality could be chosen. The number of schools that were chosen from each municipality was determined through the use of a method called a proportionate stratified sample. This is due to the fact that the proportionate stratified sampling method assures an increased proportion of the population represented in the sample as compared to the whole population, and that the sample also includes representation of the minority components of the population (Nworgu, 2013) . The respondents from each school were chosen using the same method of sampling, which was a straightforward random selection. The actual responders from each of the schools located within the municipality were chosen using a method known as simple random sampling, which is similar to a lottery.

3. Result and Discussion

The gender breakdown of the people that participated in the investigation is presented in the numbers presented in Table 1. Two hundred nineteen people participated in the data gathering and provided responses. Among this group, there were 134 men (61.2%), while there were 85 ladies (38.8%).

Research question 1: What are the emotional reactions of instructors who teach in inclusive schools?

In accordance with the data shown in Table 2, the respondents’ inclusive classrooms prompted negative or negative and terrible emotional emotions from them. This is because a bigger majority of them replied positively to practically all of the items that were put up to evaluate the emotional reactions of instructors. The reason for this is: in particular, the respondents concurred with the statement “I feel proud of myself after teaching wards with exceptional needs” (mean = 3.1370, standard deviation = 0.74775). The average number of respondents who agreed with the statement “I feel humiliated when teaching wards with special needs” was 1.6530, with a standard deviation of 0.74077 (mean vs. standard deviation). The majority of respondents (88.72% of them) were of the opinion that teaching exceptional wards was a challenging job. In addition, the majority of responders (84.87%) concurred that educating outstanding wards frequently left them feeling exhausted. In addition, 81.79 percent of respondents shared the opinion that they experienced a lack of appreciation when working with exceptional wards. The statement “I feel helpless while educating wards with exceptional needs” was the one to which the fewest number of respondents agreed; yet, even this statement was supported by more than half of the respondents. To be more specific, 50.51 percent of those who responded agreed with that assertion. It is abundantly obvious, as a general rule, that trained instructors do not possess the appropriate skills for dealing with pupils who have extraordinary needs.

Research Hypotheses 1: Coping mechanisms will not moderate emotional reactions and burnout of instructors.

As is evident from Table 3, the coping strategy that was used by the instructors was put into the first model so that its influence could be investigated. The

![]()

Table 1. Distribution of the respondents by gender.

Source: Field survey (2023).

![]()

Table 2. Means and standard deviation on the measure of emotional reactions of instructors who teach in inclusive schools.

Source: Field survey (2023).

![]()

Table 3. Model summary of moderator analysis of coping mechanism on emotional reactions on the burnout of instructors.

Source: Field survey (2023).

argument that is going to be made in this piece of writing is that the existence of the moderating variable may make it possible for the independent variable to exert a greater amount of influence on the variables that are being moderated. The observations that are presented in Table 3 show that the component of emotional reaction achieved statistical significance when the coping technique that was used by instructors was included in the first model. This is indicated by the fact that the component of emotional reaction achieved statistical significance. During the testing of the model, this was the situation. There was found to be a change in R2 equal to 4.1% (0.041 × 100 = 4.1%), which is a percentage increase in the variance that can be ascribed to the introduction of the interaction term. This change was proven to be 4.1% (0.041 × 100 = 4.1%). The data shown in the table reveals that there has been a growth in this variable that is statistically significant (p less than 0.00). As a consequence of this, one can arrive at the following conclusion: using coping methods will assist teachers in controlling their emotional responses and avoiding burnout. As a result, it is possible to draw the conclusion that the level of impact that emotional responses can have on the level of burnout (such as starting to feel as though they give more than they get back when they instruct unusual wards and becoming tensed about instructing in an inclusive setting) can have on the degree of burnout experienced by instructors and that this level of impact can be moderated by the coping mechanisms that are utilised by those instructors.

Research Hypotheses 2: There is no statistically significant relationship between instructors coping mechanism and their burnout.

As evident from Table 4, Pearson’s Product Moment correlation (r) was used in order to analyse the data in order to determine whether or not there is link between the coping strategy that teachers employ and the amount of burnout that they experience. The findings that are presented in the table indicate that there is a correlation that is statistically significant to a moderate degree between the choice of coping mechanism utilised by the teacher respondents and their level of burnout in the classroom (r = 0.552; n = 219; p-value = 0.00 is less than 0.05). This correlation is revealed by the fact that there is a modest degree of statistical significance. As a consequence of this, the null hypothesis has been shown to be incorrect, and there is a correlation that can be considered statistically significant between the coping techniques that are used by instructors and the degree of burnout that is experienced by those instructors. The existence of a positive correlation between the two variables shows that an increase in the coping strategy of choice among teachers would lead to an increase in the level of burnout experienced by those teachers (this is assuming, of course, that instructors are able to make suitable choices of coping mechanisms). For the coefficient of determination, the value of 0.30 was found to be appropriate (R2). This suggests that their choice of coping strategy for teaching accounted for thirty percent of the variance in the degree to which they suffer burnout when teaching in the classroom. [Citation needed] The data suggest, in general, that the choice of coping strategy for teaching has only a little link with the amount of burnout experienced by teachers who work in mainstream schools.

4. Discussion

4.1. Emotional Reactions of Instructors Who Teach in Inclusive Schools

The outcomes of the poll revealed that the vast majority of teachers who took part in the survey experience adverse or unfavourable emotional responses when

![]()

Table 4. Correlation (Pearson) of the coping mechanism of instructors on teaching and their classroom burnout in their inclusive classrooms.

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). Source: Field survey (2023).

they are in inclusive classrooms. This discovery offered assistance for the research results of Anaglooso (2018) , who investigated in Benin City, Nigeria, and discovered that educators working in public schools had poor sentimental responses when faced with the challenging attitudes in their schools. According to what he discovered, the bulk of teachers resort to physical aggression against their students by employing insults and other types of physical punishment, both of which he considered to be unacceptable. He said that it was discovered that a teacher had hit a student at one school because the student had refused to answer the teacher’s question while the class was in session. According to what he stated, the event took place at a single school. In an investigation that Onuwegbu and Enwuezor (2017) carried out in Jos, Nigeria, to investigate instructors’ responsiveness towards inclusive education, they found that 71% of the 270 instructors working in inclusive schools had adverse emotional responses towards their learners. This was the conclusion of their investigation. This was the finding that was most surprising to the researchers. Onuwegbu and Enwuezor came to the conclusion that some of the pupils may have had special cases that need for sensitivity when dealing with them. When teachers are forced to incorporate students with distinct requirements in their routinely planned courses due to pressure from administrators, inclusivity begins to take shape. Some of the instructors wind up becoming angry and disappointed as a result of the learners’ behaviour. According to research conducted by Smith (2016) , inclusive schools in Plymouth, England, elicited good emotional responses from the teaching staff. He claimed that the instructors felt that they could handle the issues which were presented by the pupils, and that this was one of the reasons that they displayed good feelings. Ninety-two percent (92%) of the 110 instructors that participated in the investigation revealed good emotional responses in inclusive classrooms. Per the social construction theory, the nature of reality is predetermined by society. This is only true in theory. Per Ruben (2017) , out of the 325-community people in Limbe, Cameroon, 310 of them anticipated that instructors would have greater emotional resilience than other government employees. Their rationale was that educators had access to a wealth of knowledge and the ability to overcome any obstacle that may stand in their path. This idea, which is held by members of the community, is socially built, according to the perspective of the social construction theory, even though it might not necessarily be the case in fact. According to the results of this investigation, educators demonstrated unfavourable or inadequate emotional reactions in their inclusive classes.

4.2. Coping Mechanisms Moderating Emotional Reactions and Burnout of Instructors

Per the result of the investigation, coping mechanisms help instructors manage their emotional reactions and prevent burnout. This investigation is in line with previous research conducted in Bukoba, Tanzania. Per the outcome of Smith and Smith (2000) ’s research, the effect of burnout on instructors is tempered by their sense of self-efficacy. He explained that the coping technique that a person uses in order to manage their burnouts can have a moderating effect on the symptoms of burnout that the person suffers. Demchack (2018) has a viewpoint that is somewhat dissimilar to this one. In an investigation that he carried out in Eger, Hungary, he observed that the influence of emotional responses on the burnout of pre-service teachers is not lessened by the coping methods that they utilise in order to control their burnouts and behavioural responses. This was one of the findings of his investigation. He stated that emotional reactions and burnout are distinct ideas that exist in isolation from one another; hence, the coping technique that an individual chooses to utilise will not necessarily have an effect on the way emotional reactions contribute to burnout. Because of the fact that an individual is free to choose how they would react emotionally in any given situation, it might be problematic to side with Demchack’s results. It is a choice that each individual must make; making the appropriate choice has the potential to lessen or eliminate part of the feelings of burnout that are experienced by each individual. The decision in this context refers to the method of coping that one chooses to employ. It is therefore possible to draw the conclusion that coping mechanisms help instructors manage their emotional responses and avoid burnout.

4.3. Relationship between Instructors’ Coping Mechanism and Their Burnout

Based on the outcomes of the inquiry, there is a good association that is relevant between the choice of coping technique that instructor respondents used and the amount of burnout they encountered while teaching. This investigation is consistent with the findings of Crovetto (2017) , who investigated in Menton, Monaco, and demonstrated that the magnitude of burnout encountered by instructors reduced when they employed suitable defence strategies to cope with their instinctive responses. This might be anticipated due to the fact that being in the thick of a burnout without understanding what to do might make a person’s situation even more difficult. This is due to the fact that burnout is considered as something that occurs when a person is unable to manage with the stress that is associated with their place of employment. Burnout is also associated with worsened social ties, long-term weariness, and a decreased enthusiasm in the job (Maslach, 1982; Ratliff, 1988; Sacco, 2011) . In the instance of instructors, if an instructor turns to alcoholism as a coping technique while he or she is experiencing burnout and has learners whose behaviours need to be modified (maladaptive behaviour), the teacher may find that they are unable to cause expected adjustments. The conclusion was in line with the result provided by Waldron et al. (2011) obtained at Buena Vista, Gibraltar. Torres (2017) discovered that there was a moderately negative association between the type of coping method that teacher respondents used and their level of burnout in the classroom. A value of 0.76 was obtained for the coefficient of determination (r2). This indicates that coping mechanism is responsible for explaining 76% of the variance in burnout among instructors.

5. Conclusion and Recommendation

In conclusion, the process of education may be seen as both an art and a science, with its success depending on a wide range of factors. These aspects included the type of training that the instructor has received, his or her feelings and reactions, the group of friends that the teacher maintains, the manner in which the instructor handles difficult situations, as well as the activities and happenings that rob the instructor of joy and effort. It is possible, on the basis of the findings of the inquiry, to reach the conclusion that educators who operate in situations that are emotionally inclusive are more prone to experience burnout and emotional responses. The investigation also found that the preference of means of coping is a critical factor in influencing the level of burnout encountered by educators who perform in inclusive schools in the Offinso municipality and educate learners with exceptionalities. The research has uncovered something new regarding the moderating effects of the coping mechanism on the level of burnout experienced by instructors who work in inclusive schools in the Offinso municipality and educate wards with unique and uncommon school needs. Such wards have disabilities.

The results of the research showed a direct connection between the emotional responses of instructors and the level of burnout experienced by instructors in the classroom. On the basis of these findings, the Ghana Education Service should engage clinical psychologists and counsellors. This can be achieved through the Guidance and Counselling Unit and Special Education Division, in partnering with other Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), to equip instructors with strategies available to such folks to combat symptoms of burnout. During these types of meetings/workshops, instructors need to have it driven home to them that burnouts are a natural part of being human, and that it is necessary for everyone, including instructors, to develop strategies for overcoming them.

Additionally, counsellors as well as clinical psychologists should urge instructors to really get to know more about themselves, particularly what they are capable of and what they are not capable of doing. This is extremely important since caring for and instructing exceptional wards requires the carer or instructor to cultivate a good attitude and be prepared to instruct the youngsters. In addition, all instructors, and particularly those who instruct exceptional learners to cultivate a love of lifelong learning, need to be educated by licenced counsellors and clinical psychologists. This will make it possible for the instructors to stay current with new techniques for working with the learners. This is crucial because when presented with stress, individuals do not always turn to the right coping mechanisms, and they need to be taught, counselled, and directed in their exercise in order to adopt these healthy attitudes.