Solving the Interval-Valued Linear Fractional Programming Problem ()

1. Introduction

While modeling practical problems in real world, it is observed that some parameters of the problem may not be known certainly. Specially for an optimization problem it is possible that the parameters of the model be inexact. For example in a linear programming problem we may have inexact right hand side values or the coefficients in objective function may be fuzzy (e.g. [1]).

There are several approaches to model uncertainty in optimization problems such as stochastic optimization and fuzzy optimization. Here we consider an optimization problem with interval valued objective function. Stancu, Minasian and Tigan ([2,3]), investigated this kind of optimization problem. Hsien-Chung Wu ([4,5]) proved and derived the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) optimality conditions for an optimization problem with interval valued objective function.

A fractional programming problem is the optimizing one or several ratios of functions (e.g. [6]). Such these models arise naturally in decision making when several rates need to be optimized simultaneously such as production planning, financial and corporate planning, health care and hospital planning. Several methods were suggested for solving this problem such as the variable transformation method [7] and the updated objective function method [8]. Several new methods are proposed ( e.g. [9-11]). The first monograph [12] in fractional programming published by the first author in 1978 extensively covers applications, theoretical results and algorithms for single-ratio fractional programs (see [13,14]).

Here first we introduce a linear fractional programming problem with interval valued parameters. Then we try to convert it to an optimization problem with interval valued objective function.

In Section 2 we state some required preliminaries from interval arithmetic. In Section 3 the interval valued linear fractional programming problem is introduced. In Section 4 we solved numerical examples. Finally Section 5 contains some conclusions.

2. Preliminaries

We denote by  the set of all closed and bounded intervals in

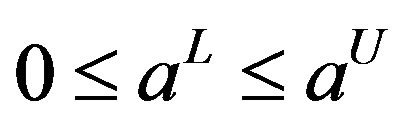

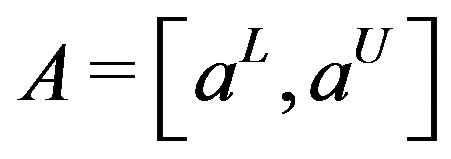

the set of all closed and bounded intervals in . Suppose

. Suppose , then we write

, then we write  and also

and also . We have the following operations on

. We have the following operations on  (note that throughout this paper our intervals considered to be bounded and closed):

(note that throughout this paper our intervals considered to be bounded and closed):

(i)

(ii)  ;

;

(iii)

where  is a real number and so we have

is a real number and so we have

Definition 2.1. If  and

and  are bounded, real intervals, we define the multiplication of

are bounded, real intervals, we define the multiplication of  and

and  as follows:

as follows:

where

where . For example if

. For example if  and

and  are positive intervals (i.e.

are positive intervals (i.e.  and

and ) then we have:

) then we have:

(1)

(1)

and if  and

and  then we have:

then we have:

(2)

(2)

There are several approaches to define interval division. Following Ratz (see [15]) we define the quotient of two intervals as follows:

Definition 2.2. Let  and

and  be two real intervals, then we define:

be two real intervals, then we define:

We observe that the quotient of two intervals is a set which may not itself be an interval. For example, . Given definition 2.2, The Ratz formula [15] is given by the following Theorem:

. Given definition 2.2, The Ratz formula [15] is given by the following Theorem:

Theorem 2.1. ([15]) Let  and

and

be two nonempty bounded real intervals.

be two nonempty bounded real intervals.

Then if  we have:

we have:

(3)

(3)

Theorem 2.2. (see [16]) If  and

and  are nonempty, bounded, real intervals, then so are

are nonempty, bounded, real intervals, then so are , and

, and . In addition, if

. In addition, if  does not contain zero, then

does not contain zero, then  is also a nonempty, bounded, real interval as well.

is also a nonempty, bounded, real interval as well.

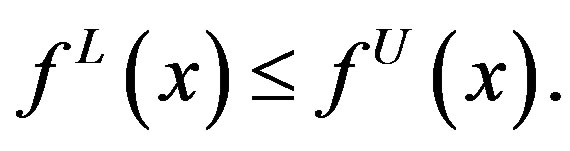

Definition 2.3. A function  is called an interval valued function (because

is called an interval valued function (because  for each

for each  is a closed interval in

is a closed interval in ). Similar to interval notation, we denote the interval valued function

). Similar to interval notation, we denote the interval valued function  with

with  where for every

where for every

are real valued functions and

are real valued functions and

Proposition 2.1. Let  be an interval valued function defined on

be an interval valued function defined on . Then

. Then  is continuous at

is continuous at  if and only if

if and only if  and

and  are continuous at c.

are continuous at c.

Now, here we introduce weakly differentiability.

Definition 2.4. Let  be an open set in

be an open set in . An interval valued function

. An interval valued function  with

with

is called weak differentiable at

is called weak differentiable at  if the real valued functions

if the real valued functions  and

and  are differentiable (usual differentiability) at

are differentiable (usual differentiability) at .

.

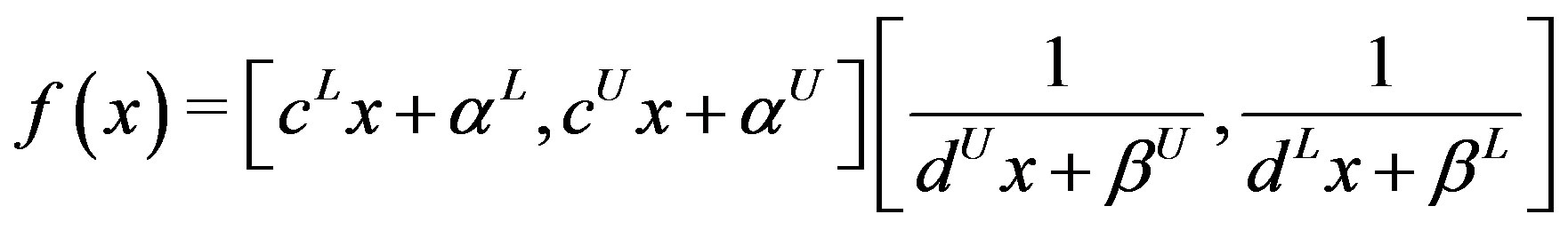

Definition 2.5. We define a linear fractional function  as follows:

as follows:

(4)

(4)

where

and

and  are real scalars.

are real scalars.

Remark 2.1. Note that every real number  can be considered as an interval

can be considered as an interval .

.

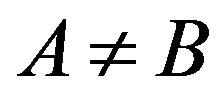

Definition 2.6. To interpret the meaning of optimization of interval valued functions, we introduce a partial ordering  over I. Let

over I. Let ,

,  be two closed, bounded, real intervals

be two closed, bounded, real intervals , then we say that

, then we say that , if and only if

, if and only if  and

and . Also we write

. Also we write , if and only if

, if and only if  and

and . In the other words, we say

. In the other words, we say  if and only if:

if and only if:

or

or  or

or

3. Interval-Valued Linear Fractional Programming (IVLFP)

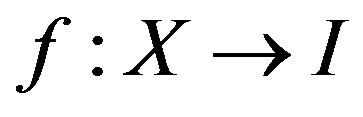

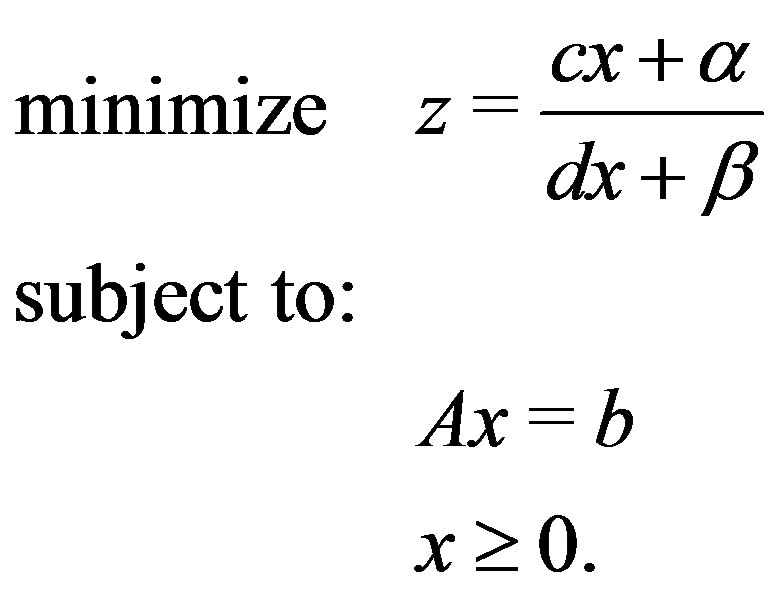

Consider the following linear fractional programming problem:

(5)

(5)

First consider the linear fractional programming problem (5). Suppose that

where , we denote

, we denote  and

and  the lower bounds of the intervals

the lower bounds of the intervals  and

and  respectively (i.e.

respectively (i.e.  and also

and also

where

where  and

and  are real scalars for

are real scalars for ) and

) and , similarly we can define

, similarly we can define  and

and . Also

. Also ,

, . So we can rewrite (5) as follows:

. So we can rewrite (5) as follows:

(6)

(6)

where  and

and  are interval-valued linear functions as

are interval-valued linear functions as

and . So for example we have:

. So for example we have:  and

and . Finally from (6) we have:

. Finally from (6) we have:

(7)

(7)

To introduce an interval-valued linear fractional programming problem, we can consider another kind of possible linear fractional programming problems as follows:

(8)

(8)

where  and

and  are linear fractional functions (as in definition 2.5). Also we may have interval-valued linear fractional programming in the form (7):

are linear fractional functions (as in definition 2.5). Also we may have interval-valued linear fractional programming in the form (7):

(9)

(9)

Theorem 3.1. Any IVLFP in the form IVLFP(2) (see Equation (9)) under some assumptions can be converted to an IVLFP in the form IVLFP(1) (see Equation (8)).

Proof. The objective function in (9) is a quotient of two interval valued functions ( and

and ). To convert (9) to the form (8), we suppose that

). To convert (9) to the form (8), we suppose that  for each feasible point

for each feasible point , so we should have:

, so we should have:

(10)

(10)

or

(11)

(11)

for each feasible point . Using theorem 2.1, because the denominator doesn’t contain zero we can rewrite the objective function in (9) as:

. Using theorem 2.1, because the denominator doesn’t contain zero we can rewrite the objective function in (9) as:

(12)

(12)

Now we can consider two possible states:

Case (1). When , we have two possibilities:

, we have two possibilities:

(i) When , using Definition 2.1, we have:

, using Definition 2.1, we have:

(13)

(13)

(ii) When , by Definition 2.1, we have:

, by Definition 2.1, we have:

(14)

(14)

Case (2). When , we have two possibilities:

, we have two possibilities:

(i) When , by Definition 2.1, we have:

, by Definition 2.1, we have:

(15)

(15)

(ii) When , by Definition 2.1, we have:

, by Definition 2.1, we have:

(16)

(16)

(Note that the subcase  easily can be derived from above cases, because in this state,

easily can be derived from above cases, because in this state,  implies that

implies that ). Now according to theorem 2.2, and considering above cases, the objective function in (7) can be rewritten as follows:

). Now according to theorem 2.2, and considering above cases, the objective function in (7) can be rewritten as follows:

(17)

(17)

where the objective function is an interval valued function and  and

and  are linear fractional functions (according to the corresponding case (13) - (16)), and this completes the proof.

are linear fractional functions (according to the corresponding case (13) - (16)), and this completes the proof.

Now following Wu [5], we interpret the meaning of minimization in (17):

Definition 3.1. (see [5]) Let  be a feasible solution of problem (17). We say that

be a feasible solution of problem (17). We say that  is a nondominated solution of problem (17), if there exist no feasible solution x such that

is a nondominated solution of problem (17), if there exist no feasible solution x such that . In this case we say that

. In this case we say that  is the nondominated objective value of

is the nondominated objective value of .

.

Now consider the following optimization problem (corresponding to problem (17)):

(18)

(18)

To solve problem (17), we use the following theorem from [5].

Theorem 3.2. If  is an optimal solution of problem (18), then

is an optimal solution of problem (18), then  is a nondominated solution of problem (17).

is a nondominated solution of problem (17).

Proof. See [5].

4. Numerical Examples

This section contains three numerical examples which are solved by the new proposed approach. Example 4.3 introduces an application of IVLFP.

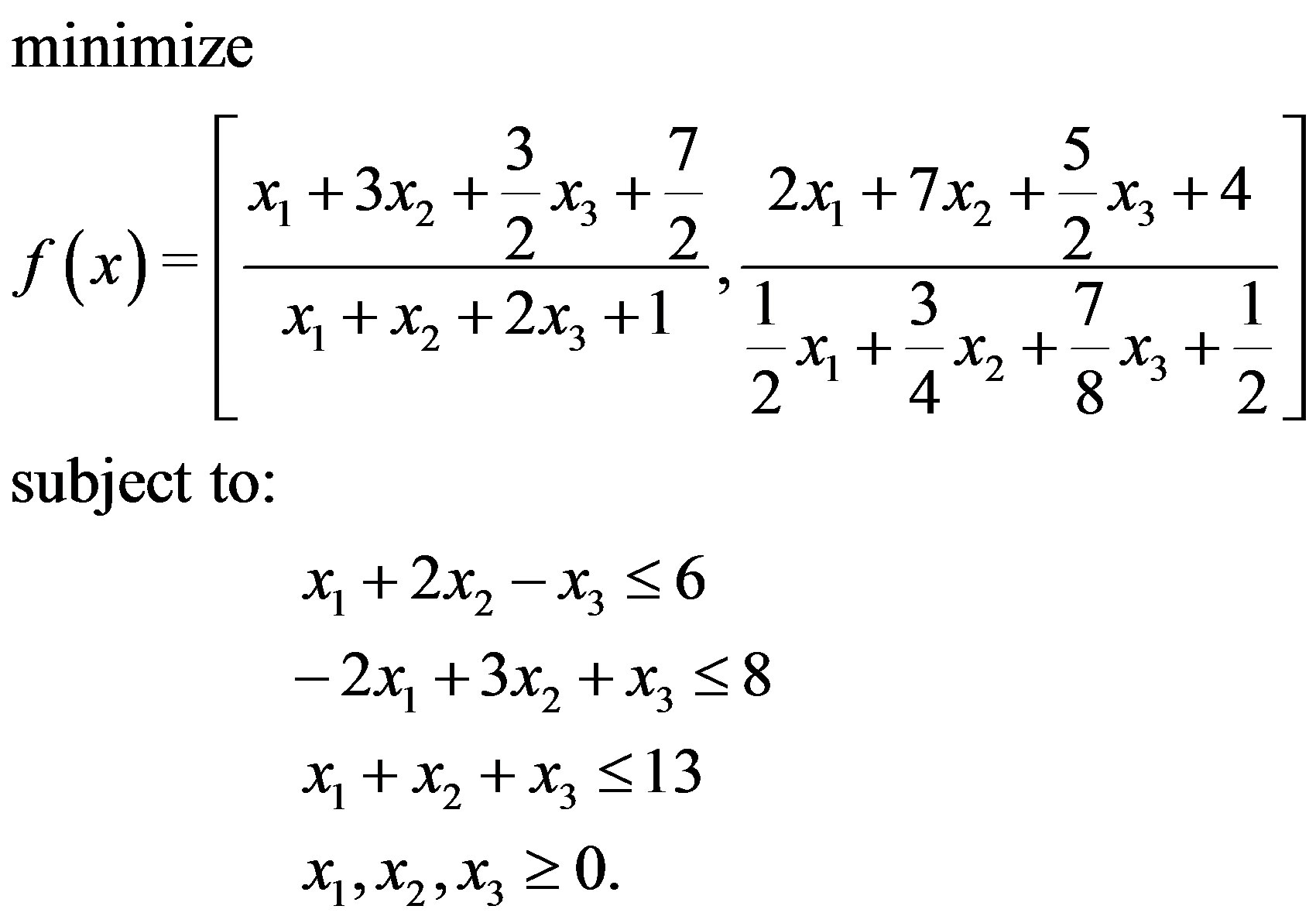

Example 4.1. Consider the following optimization problem:

(19)

(19)

We see that here

and

.

.

So because  we have

we have  and also

and also  so we should apply case (1)(i). Finally we will have the following optimization problem:

so we should apply case (1)(i). Finally we will have the following optimization problem:

(20)

(20)

Now to obtain a nondominated solution for (20), we use theorem 3.2. and solve the following optimization problem:

(21)

(21)

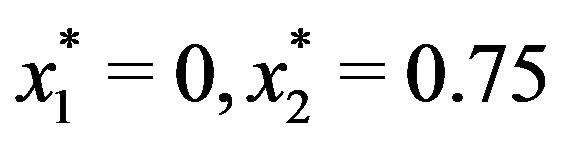

The optimal solution is  with optimal value

with optimal value .

.

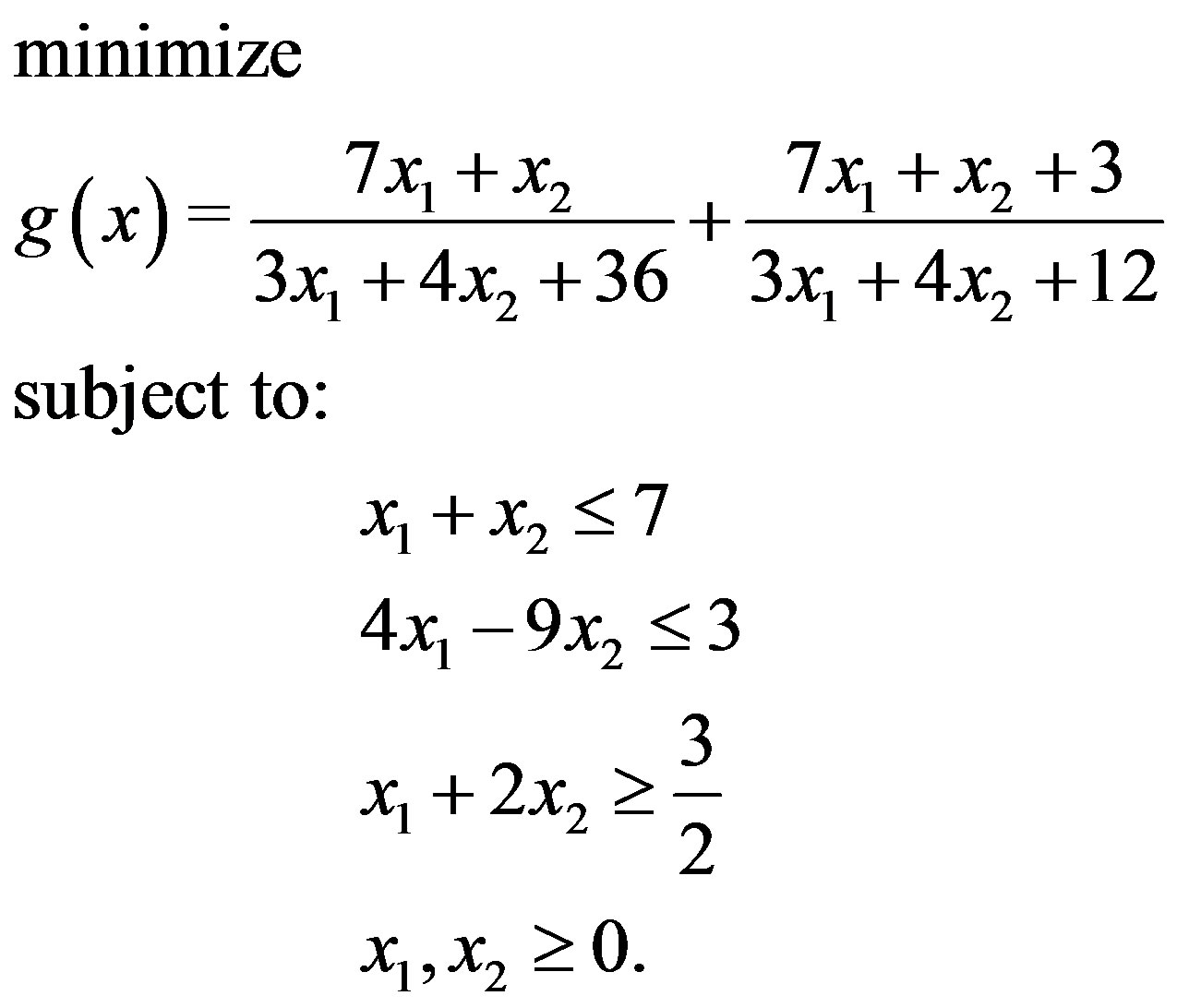

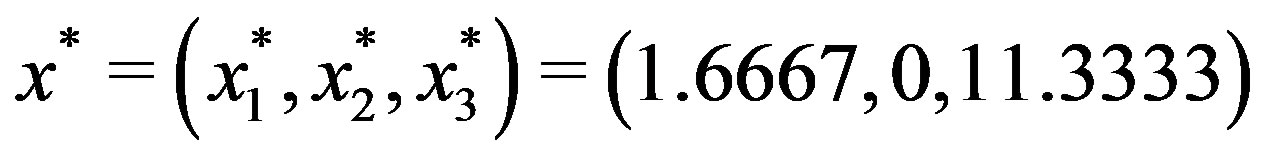

Example 4.2. Now consider the following optimization problem:

(22)

(22)

By Theorem 3.1, we can convert (22) to the following problem:

(23)

(23)

Now we can apply Theorem 3.2, and solve the optimization problem:

(24)

(24)

Finally a nondominated solution for (22) is

with

with

, which is the optimal solution of (24).

, which is the optimal solution of (24).

Example 4.3. Consider the following applied problem from [17]:

A company manufactures two kinds of products ,

,  with a uncertain profit of

with a uncertain profit of ,

,  dollar per unit respectively. .However the uncertain cost for each one unit of the above products is given by

dollar per unit respectively. .However the uncertain cost for each one unit of the above products is given by ,

,  dollar. It is assumed that a fixed cost of

dollar. It is assumed that a fixed cost of  dollars is added to the cost function due to expected duration through the process of production and also a fixed amount of

dollars is added to the cost function due to expected duration through the process of production and also a fixed amount of  dollar is added to the profit function. If the objectives of this company is to maximize the profit in return to the total cost, provided that the company has a raw materials for manufacturing and suppose the material needed per pounds are 1, 3 and the supply for this raw material is restricted to 30 pounds, it is also assumed that twice of production of

dollar is added to the profit function. If the objectives of this company is to maximize the profit in return to the total cost, provided that the company has a raw materials for manufacturing and suppose the material needed per pounds are 1, 3 and the supply for this raw material is restricted to 30 pounds, it is also assumed that twice of production of  is more than the production of

is more than the production of  at most by 5 units. In this case if we consider

at most by 5 units. In this case if we consider  and

and  to be the amount of units of

to be the amount of units of ,

,  to be produced then the above problem can be formulated as

to be produced then the above problem can be formulated as

(25)

(25)

The optimal solution is ,

,  with the objective value

with the objective value

5. Conclusion

In this paper, first we introduced two possible types (Equations (8), (9)) of linear fractional programming problems with interval valued objective functions. Then we proved that we can convert the problem of the form (9) to the form (8). By solving (8), we obtained a nondominated solution for original linear fractional programming problem with interval valued objective function. Work is in progress to apply and check the approach for solving nonlinear fractional programming problems as well as for quadratic fractional programming problems.