The Class of Language: Examining Rhetoric, Children’s Social Education, and Pedagogy in Economically Distinct Classrooms ()

1. Introduction

In this paper, I examine the uses of language in a Rochester city public elementary school and in a Rochester suburban, accelerated after school program. I entered this research ethnographically, thinking of the following questions: how do teachers and students employ language in these dissimilar classrooms? Are rhetorical variations between the two indicative of their economic, social, and racial differences? If so, are uses of language that reflect sociopolitical identities and standings influential upon the way children behave and think? That this research suggests the answers to these questions are more affirmative than not, the issue of how rhetorical choices implicitly teach children certain values and ways of behaving becomes an urgent focus for anyone interacting with children, especially those interacting with children in an educational space.

I have changed the names of each location as well as the children you will hear about. The first facility, which I will call Leap Ahead (as this is a slogan the facility often uses in marketing) is an accelerated learning center in middle to upper class suburbia. Students there are mainly white and their families are typically economically privileged residing in the middle to upper class. Leap Ahead’s entire facility is founded upon the idea of children “getting ahead” and “becoming advanced.” In particular, the school-age program, which I am a teacher for, is marketed as extracurricular enrichment for school-agers that want to be challenged. Leap Ahead defines itself as a place in which children are learning in a way that will supposedly better prepare them for their futures. On the other hand, the classroom I assist at a Rochester city public school, which I’ll call School #10, is a “catch-up” room. These students are usually Latino whose families often live in economically depressed areas within the city of Rochester. Here, children of different ages are placed together based on a relatively similar aptitude for the English and Spanish languages. Usually, there are an overwhelming number of older children (eight to nine year olds) who have “fallen behind” in reading, writing, and math. In response to their lower grades and perceived aptitude, teachers and school administration place these children in this room with six and seven year olds. From my experience working in both places and from my observations―including visual, written, and auditory recordings over the course of three weeks―I have located salient differences in the way language operates in these two institutions: namely in relation to appropriate and forbidden words, disciplinary tactics, lesson plans, and social bonding within the classroom. In other words, teachers in different socioeconomic classrooms employ and thus provide students with different access to language, which in turn affects their relations with their peers, the curriculum, and their perceived potential in the present or future. This indicates that children are receiving starkly different structural education as well as social education due to their teacher’s rhetoric suggesting that a change in language use can result in a change in quality of education, regardless of the classroom’s class status.

2. Appropriateness and Taboos―Language That Is Forbidden

The first prominent difference I noticed between the two facilities related to what was considered appropriate at Leap Ahead versus School #10. School #10 has a wider allowance for words; they don’t consider as many words inappropriate and harmful as Leap Ahead does. For example, Leap Ahead disallows “potty words,” which includes anything that relates to the potty: poop, fart, pee, barf. What you are to say instead of “I have to pee” is “I have to go to the bathroom” or better yet, “May I excuse myself.” In fact, I myself have gotten in trouble with my director numerous times for saying fart instead of “toot”. Among a roomful of kids that have zero wish to control their gaseous desires it gets pretty annoying and feels pretty arbitrary to check myself before pleading, “Let’s all stop farting!” This need to consciously correct myself, especially since a lot of the inappropriate words seem strangely and arbitrarily deemed is not enforced at School #10. There, children can say whatever word they like as long as it doesn’t hurt themselves or other people. So, saying “I have to poop” is appropriate, but saying “You are poop” is unacceptable.

Beyond inappropriate words, there are forbidden words. Generally, these are the same at both places, namely being curse words. However, Leap Ahead, again, adds a couple more to their list. At Leap Ahead, it isn’t merely inappropriate to say “hate” or “stupid,” it is entirely forbidden. Those words are believed to have no positive or necessary quality whatsoever, meaning one should always be able to find a different more suitable word for how they’re feeling. At School #10, on the other hand, you can pretty much guarantee that on any given day you will hear one of the two teachers say to a child, “I hate that you did that” or “Are you serious? That was very stupid.” Sometimes it’s just a simple “Stop being stupid.” This is just the beginning of more signs that show how School #10 doesn’t edit itself: it reveals impatience, disapproval, ugly moods, excitement, or passion for different behaviors and subject materials, even if that revelation is somewhat off-putting.

Consequently, children adopt this language and apply it to their own behavior as students at School #10 tell each other to “Stop being stupid” throughout the day and at a much higher rate than at Leap Ahead. At the same time, School #10’s students adopt their teacher’s insensitive language to the detriment of harmony with their peers, they also adopt their teacher’s impassioned language to the betterment of effective pedagogy. Perhaps because their teachers don’t edit their language around their students, the children also don’t edit their language regarding subject material. In fact, one day a girl, Yajaira, stood up during a lesson on Abraham Lincoln and yelled, “I hate that we’re learning about another dead guy.” While lacking the finesse and censorship that Leap Ahead encourages in their students (“We don’t say hate”), Yajaira’s emotional and unedited reaction at School #10 was clear and honest. It was also effective as the next day, the teachers had prepared a lesson on then President Barack Obama much to Yajaira’s and the rest of the class’s delight. Instead of reprimanding her, Yajaira’s teachers responded to her raw and unfiltered comment seriously and edited their lesson plan, which ultimately captivated their students’ interest and highlighted their students’ perceived agency in school.

Meanwhile, Leap Ahead seems to value a different definition―not better or worse―of professionalism in which the teacher should always be a model for students to look up to: composed, compassionate, calm, and caring, even if that model is somewhat censored. If Yajaira were to stand up and voice the same complaint with the same words during a Leap Ahead lesson, the Leap Ahead teachers would reprimand her use of “hate” and “dead guy” and likely continue the lesson without appreciating the message behind her words, let alone the valid emotions to her words. Even when Mary, a young girl at Leap Ahead, raised her hand to make a relevant comment concerning the lesson on plant and animal cells, her use of the word “dumb” discredited her point. “So how is it,” Mary calmly questioned, “that animal cells and plant cells are so similar but plants are so much dumber than animals?” Essentially asking if cells influence the abilities and functions of an organism, a rather astute question for a seven-year-old, the maturity in Mary’s comment went unnoticed as her teachers quickly reprimanded her for saying “dumb” and continued their next lesson. According to the Leap Ahead teachers, one must relay their message “appropriately” and formally. A child’s inclusion of “inappropriate” or informal words supersedes the inquiry, suggestion, or critical thought behind their words. Yet, at School #10, teachers often ignore a child’s inappropriate language and even display their own “inappropriate language” (such as saying “stupid” or “hate”), which results in more germane conversations between students and teachers during lessons.

3. Discipline―Language When Reprimanding

This brings me to the second difference between Leap Ahead and School #10. This difference relates to the value disparities that the facilities’ policies on and reactions to appropriate and inappropriate words began to question: how much agency does our language inculcate in students? Do we give children the chance to reflect on their actions or do we just tell children what we want from them? Disciplinary methods at Leap Ahead revolve around the child’s agency by encouraging their reflective and autonomous growth. Looking back at recordings, whenever a child misbehaved by breaking one of the well-known rules (such as being rude, running inside, or not using “indoor voices”) a teacher would always reprimand them with, “Do you think that was a good choice?” or “What should you have done instead?” At School #10 (both establishments generally have the same rules regarding behavior), if a child runs inside, speaks out of turn, or is too loud, the common response from the teacher tends to be more declarative: “Don’t do that,” “Stop that right now,” or “Go read a book.” School #10’s method negates a space for the child’s reflection, immediately directing them to cease the action or to start another activity instead. Meanwhile, the method at Leap Ahead is to try and enforce children’s recognition as to what they did and why it was wrong.

Each difference leads to benefits and repercussions in the child’s demeanor. At Leap Ahead, children often seize the opportunity for autonomous reflection as a way to further resist the rules. When asked if they think their unsafe or inappropriate action was a good choice, many kids have started to respond with a simple and defiant “yes” or a more detailed, “Well, I thought it was a good choice because…” and insert always amusing excuse here. Providing them a site to reflect easily turns into defiance at the rule in general. Still, placing responsibility on the child to understand their actions can also lead to reasoning, as one child told another who had just been running inside, “We don’t run inside because if we fall there are a lot of things we can hurt ourselves on or hit our head on and then we’d be really upset.” At School #10, a more direct and short disciplinary method is more efficient in that the children do what you ask of them without “talking back” or taking too long. At the same time, though, they are yelled at far more often, because usually they don’t understand why they’re being yelled at and will repeat the misbehavior later. They don’t equate their actions to misconduct because teachers don’t as consistently explain to them why what they did was unsafe or inappropriate. Teachers don’t give children at School #10 time to think about it themselves.

You’ll notice that the amount of autonomy and reflection encouraged in children during disciplinary linguistic moments is different than during instructive linguistic moments. At School #10, teachers didn’t pause to reprimand a student’s inappropriate language as long as they were engaged with the topic at hand. At Leap Ahead, however, teacher’s completely dismissed a child’s comment if it contained inappropriate language; they chose to discipline without responding to the child’s question or thought. Thus, at a greater extent than School #10, Leap Ahead is far more concerned with developing children’s “appropriate” behavior and “appropriate” use of language (and remember that they consider far more words inappropriate than School #10). Crediting this even more, one evening when a parent picked their child up from Leap Ahead, their child said their day was “stupid awesome” (a word combination at which I could not help but giggle). In response, their parent said, “After all these years at Leap Ahead, you should know we don’t talk like that,” asserting that Leap Ahead teaches a certain standard for language use. This parent’s statement also implies that it takes “years,” not to mention a lot of money, at an accelerated, after-school program for children to come across and absorb such lessons on behavior and speech. Part of the shared understanding at Leap Ahead is that you are paying for “better behaved” children. Yet, from the way Leap Ahead teachers minimize engaged learning and teaching to emphasize discipline, I wonder what consequences there are to their censorship of language? To answer this question, I examined their language and School #10’s language during lesson plans more comprehensively. In found that Leap Ahead indeed encourages reflective thought when it comes to misbehavior, but discourages it during lesson plans (which is the opposite when it comes to School #10).

4. Lesson Plans―Language When Teaching

In other words, language used during lesson plans encourages different levels of understanding: asking why we are learning this and how it will apply to our lives is supported differently at each place, largely due to a difference in the “temporal positioning” of their language; School #10’s use of language is focused on the present, while Leap Ahead’s use of language is focused on the future. As a way to hopefully avoid any bias before conducting this research I tried to be as conscious as possible. I tried not to assume or read more into a situation or observation than was actually there. While two books, Geneva Smitherman ’s Talkin that Talk and Shirley Brice Heath ’s Ways with Words, inspired this research, I didn’t want to insert any of their arguments or ideas concerning language and education onto the people or into the situations at these facilities. Evidential in Deborah Tannen’s book, Conversational Style, which quantitatively and qualitatively examines a conversational Thanksgiving Dinner, language is a dynamic, complex, and sometimes fragile tool that people use, manipulate, and access for different reasons at different times. Consequently, I felt that it would be unfair to these facilities, people, and the communities they represent to conduct this research with preconceived notions of what I might find. Very much, I entered this with as little partiality and preconception as I could.

With that said, looking back, I feel that I can deduce many similarities between the variations among Leap Ahead’s and School #10’s educational discourse to the ones Heath gathered between Trackton and Roadville (of the Piedmont region in North Carolina). Much like in the white, working-class community of Roadville, the kids at Leap Ahead didn’t quite understand how their reading, writing, and arithmetic lessons were applying to their individual pursuits. One girl at Leap Ahead, eight-year-old Mia, complained during numerous math lessons, “I want to be an artist and artists don’t need math!” Along the same lines, six-year-old Evan wants to be a racecar driver, so getting him to read is a marathon in itself so to speak. For School #10 there is a noticeable dissimilarity. Children there don’t have interests that conflict with their learning. Instead, they have interests that dictate their learning: seven-year-old Ishmael asked to learn more about Native Americans around Thanksgiving time, nine-year-old Alejandra always chooses animal books for her English practice, and six-year-old Nina cried when she did her writing assignment wrong, because she practices “every night in her diary.” Most of the children at School #10 are outwardly invested in their classes most days. Seeming like a surprising observation, if just by the dissimilarity to the Leap Ahead children’s attitudes, I considered it in more detail over the next couple days.

After listening to recordings for Leap Ahead lessons, I started to think that perhaps the children at Leap Ahead find math, reading, and writing so inconsequential and unimportant to themselves, because as they are being taught these skills they are also being told, “Think of your future,” and “This will be important to know when you’re older and have a job or if you want to go to college.” A disconnection might be forming in their minds in which they are always told to explore the possibilities of their future, which are wonderfully grand as children’s minds can be, but then are only taught certain subjects, which seemingly have no relation to the dreams they just imagined for their lives. Language when teaching Leap Ahead students is positioned toward the future, unintentionally resulting in a disconnect or indifference to the present. As Heath similarly notes about Roadville students, “They recognize no situational relevance; they do not see that the skills and attitudes their teachers promote make any difference in the jobs they seek,” which seems to adequately apply to the children at Leap Ahead as well (Heath 47) . Remember, Roadville and Leap Ahead have comparable student demographics: majority white, affluent, and English only speakers. Students in School #10 generally aren’t introduced to futuristically (regarding higher education or careers) focused rhetoric. Their lessons stay focused on the subject matter at hand and any encouragement to learn doesn’t prompt future ambitions, but instead spurs present interests: “Focus, this part of the book is really interesting!” or “When you learn how to multiply you can teach your friends!”

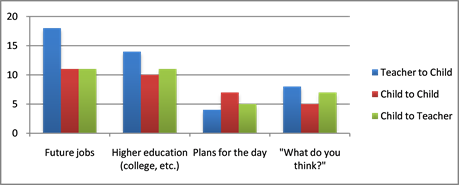

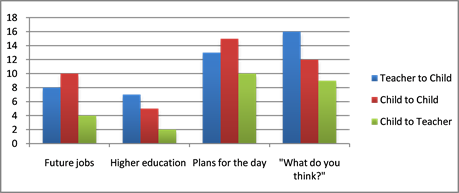

Exploring this conspicuous disparity more, I went into work at School #10 the next day with the goal of assessing the classroom and quantitatively comparing it to the Leap Ahead recordings. I decided to count the number of times four topics―first, future jobs; second, higher education such as college; third, plans relating to the current day such as games to play or dinner to eat; and fourth, asking for another to think or engaging their personal opinion in some way-were initiated by a teacher to a child, by a child to another child, and by a child to the teacher during an hour-long lesson at each institution. Below are the results for Leap Ahead.

And below are the results for School #10.

A number of observations can be deduced from these charts, but I will touch on three. First, focusing on the current day and engaging personal thoughts were more common at School #10 that day than it was at Leap Ahead. Second, at Leap Ahead the teachers seemed to set a precedent as to what an acceptable topic matter was; children often replicated the teacher’s pattern and initiated topics that their teachers had focused on. However, at School #10 this was not as concretely the case. Children initiated certain conversation topics more often, even if teachers hadn’t focused on those topics first. Third, there is a disassociation with this information and the ones I gathered regarding disciplinary strategies. Asking the students’ opinions is more common at School #10 than at Leap Ahead during lesson times. Accordingly, we see that when the language is not disciplinary but didactic (for a lesson), Leap Ahead resorts to more lecturing and telling whereas School #10 changes to a conversational and responsive mode of teaching. In other words, when children are reprimanded at Leap Ahead they have the chance to think and articulate their opinion, but when they are taught lessons (like reading, writing, history, science, and math) they are very much “taught at” instead of with.

At School #10 the opposite is true in which sites for reciprocation are open during periods of teaching and learning, yet they are closed during moments of scolding or discipline. At School #10, children asked each other what they thought nearly 3x as often as children at Leap Ahead. However, children at both institutions asked their teachers what they thought at similar rates, with children at School #10 doing it slightly more often. This suggests that the way teachers speak to each other and to students influence how students speak to each other: teachers asking students what they think during lessons at School #10 translated to students asking each others’ opinions both during and outside of lessons as well. That different language use has different effects in students is essential for effective pedagogical theory. Cultivating an environment in which students are engaged not only with the teacher and the material, but with each other is essential for a collaborative, thus productive education. Meaning, teachers must be more conscious of how their language affects and subconsciously instructs their students: are their words opening or closing reflective spaces, encouraging or discouraging reciprocity, and positioning importance and relevance in the present or in the future?

Nuancing these sites of potential reflection and reciprocation even more, I found that there is a gender discrepancy within the classroom’s language as well. The next day, with the goal to continue more detailed quantitative research (and to check if the one day’s results were not singular but were part of a pattern, which seeing as the same trend occurred every lesson plan for the next two weeks, it seems to be the case), I sat down in my chair at School #10 and took out my notebook. The teacher had written “their, there, and they’re” on the chalkboard and asked the class who knows the difference among the three. As a result, my first significant gendered observation followed.

School #10 and Leap Ahead were guilty of asking boys for their opinion more than girls. In an hour-long lesson, boys at School #10 were asked for their opinion about 2.2 times more often than girls. Boys at Leap Ahead were asked for their opinion about 1.7 times more often than girls. Yet, for every boy that raised his hand to answer a question during that same hour-long lesson at School #10, at least three girls also raised their hands. Meaning, boys were called on more than girls despite more girls wanting to answer the question. Even during lessons when boys were called on less than girls (typically when a boy didn’t raise his hand at all), the boys were subsequently asked for their opinion or further explication along with their answer, whereas that was largely neglected when a girl was called on. The same was true for Leap Ahead but on a smaller scale, though several variables could account for that such as a different boy to girl ratio in the class as well as lessons that didn’t encourage asking students for their opinion in general. Nevertheless, the encouragement of thought and response at both institutions is at least somewhat gendered. Such habitual or subconscious gendering of language means teachers must not only become more diligent about the language they use and the linguistic habits they practice, but they must also become conscious about who they tend to direct certain language to and why. Failing to be conscious of implicit gender disparities regarding language use, reaffirms a social education in which girls assume less agency and critical appreciation than boys. One step to alter this social education is to alter how we speak and respond to children in class.

About a week later, during another one of my observational hours, I noticed another nuance to the difference in teaching language between Leap Ahead and School #10. While, during lessons, School #10 asks for students’ opinions more than Leap Ahead, and while School #10 tends to ask boy students’ opinions more than girls’ (as does Leap Ahead to some degree), School #10 also corrects their students’ language when they respond. Their correction aligns, to a degree, with Smitherman’s account of African American students being told to speak in accordance with Standard English rules. In her book, Smitherman describes in Chapter 7, ‘English Teacher, Why You be Doing the Thangs you Don’t do?’ that a “whole heap” of English teachers teaching Black students “castigate” them for using a “nonstandard” dialect (Smitherman 123) . Ultimately, these white teachers don’t realize or refuse to act on the fact that their insistence on white English dialect serves to the racial hierarchy, arbitrary standardization, and socioeconomic disparity of white, English over non-white communities. What I noticed about the teachers at School #10 who are white, English-Spanish bilingual women that commute to the city for work is that they often tell their students to focus on English since they “already speak Spanish.” Think about this. These are children being told this. I’m 23, English was my first language, I have a BA in English and I’m still learning more words and more effective ways to communicate. Telling these children to disengage with Spanish in order to improve their English, however well intentioned, implicitly indoctrinates them into a hierarchy in which English, specifically white standardized English, is on top and Spanish is “useless” and “behind them.” In fact, when one of their students answers a question asked in English with Spanish they immediately correct them and tell them to answer in English, without even responding to the content of their answer. Not only are these classrooms, then, economically distinct, but they are also ethnically and culturally distinct―all of which contributes to the classrooms linguistic choices and social education.

5. Social Bonding―Language When Making Friends

This leads to one of the last observations, but perhaps one of the most thought provoking observations concerning the ways in which children pick up on social cues from the language used by their teachers and classmates: the language teachers use affects the way their students relate to one another. For example, Heriberto is a seven-year-old student in School #10. Among all his classmates, Heriberto has the darkest colored skin. As one of the most fluent English and Spanish speakers in the class comprised of six to nine year olds, he manages to finish his Spanish and English books before many in the class. He’s a sweet and smart boy who is unfortunately a great example of a bright kid growing up in a city with a struggling education system (due to economic and racial inequalities); he is, unfortunately, representative of how those structural forces can affect your social relations.

Heriberto’s classmates don’t see him as “one of them.” Many people might say that “kids will be kids” and, perhaps from observing the modes of relating in the society that surrounds them, will often pick out ones to bully, especially ones that look different. What’s of note, however, is that these students’ remarks are rarely directed toward Heriberto’s physical appearance and instead are mostly focused on his language. Despite the fact that Heriberto speaks English as well as, if not better than, most of his classmates, they often ridicule him for speech that is “slow”. One day, I had written down in my observations, Heriberto was chosen to read a book in Spanish and another in English. Proficiently completing the two, Heriberto went back to his seat with pride only for the boy next to him to giggle and remark, “Su Anglais es cómico y estúpido” meaning “Your English is funny and stupid.” Kids laughed and agreed and then were all promptly yelled at. It’s not true though. Heriberto’s English is one of the best in the class, along with his Spanish. It’s just that language, as is often what the teachers in this class choose to correct especially for English, became a way for other children to isolate Heriberto and another way to classify him as more “black” and thus less “educated” than the rest of them and somehow unlikable because of it, as one of Heriberto’s classmates said, “You should make your English more gringo” or more white.

Then there is Connor at Leap Ahead. With blonde hair, blue eyes, and a squealing giggle, Connor is that (societally construed) innocent little boy. Often, Connor goes into what Leap Ahead teachers have dubbed “Conn-eruptions” in which he has extreme emotional reactions to a situation that is surely unpleasant to him. The reason that had led to this particular observation concerning social bonding was the fact that his teacher told him to put his toy away for snack time. Being denied the chance to make his shirtless G.I. Joe action figure kick butt while eating fruit gummies, Connor ran around the room, bulldozed into a six-year-old girl, and threw crayons everywhere. A routine yelling began: “Connor, do you think you should start making better choices?!” “Connor, do you want me to call your parents?” “Connor will you be happy about this decision later?” and so on. The teacher to student disciplinary dynamic remained the same: trying to get the child to realize he should change what he’s doing instead of just telling him to change what he’s doing directly. What struck me this time, however, was the way other children reacted to him.

When I am the one responding to Connor, the kids are very active: offering to help clean his mess, asking him what’s wrong, or informing me when he’s getting upset again. In this particular instance and as a mere observer, I was able to focus on the other kids’ reactions amongst themselves as another teacher spoke with Connor. The other kids’ conversation about Connor wasn’t what I’d expect. These six to eleven-year-olds weren’t mocking his behavior; they were concerned for his future. The oldest kid at Leap Ahead(at eleven-years-old) declared, “Connor won’t make it anywhere good if he keeps acting like this” to which Tessa, a second grader, replied, “He won’t have friends when he grows up either if he always throws crayons at them.”For the kids at Leap Ahead, the issue with Connor was that he was ruining his future and potential. He wouldn’t be successful and he wouldn’t have friends “later in life.” However, they would still play with Connor later in the day when he was behaving better. Their use of language condemned Connor’s future, but did not isolate him in the present. The way children bond or segregate, then, has the potential to be a direct result from the rhetoric their parents and teachers use, which are most likely economically, racially, and politically influenced. After all, these patterns of language are even more, or perhaps only, urgent when considering the disparate primary racial and financial demographics of each facility.

6. Conclusion―Language to Adopt

The U.S. has a historical pattern of the most financially struggling public schools residing in urban areas. They are also typically comprised of more black and brown bodies than financially stable public schools (such as most suburban schools) and private schools. These facilities in Rochester, NY are no exception to this pattern. Consequently, the notable differences in structural and social education detailed in this paper are simultaneously indicative of language use and racial and class difference. So, if the noted language differences between these facilities’ teachers are related to the race and class of their respective environments, then the way children implicitly learn from rhetorical choices is racially and economically coded. A child’s racial identity and class status influences what kind of facility they can attend: a Leap Ahead or a School #10. Then, based on the facility they attend, a child’s education, including assimilation into “appropriate behavior,” senses of agency, interpersonal relations, and understanding of their future potential is drastically different. Since Leap Ahead and School #10 employ starkly different rhetoric when teaching, a student’s social and structural learning is initially and continually shaped by their family’s ethnicity, race, and economic standing. However, while I am saying that the way we use language, especially language that focuses on a child’s future or language that focuses on the child’s present situation is likely class-coded (children from more stable financial situations have more opportunities for a more stable future) and habitually class-coded, I am not saying that class-coded, racially coded, or gender coded language is unchangeable. The unending power of language use is that it is a choice. We can, with work, attention, diligence, and constant examination, use language differently to encourage different mindsets, behaviors, and effects.

What we teach in schools isn’t the only important element. How we teach, how we employ language, and how we access language are particularly essential, because every time we speak we are extending a gesture that structures the way others behave and value certain qualities. How we use language is judged and undertaken by others; every utterance can be effectively and socially charged. Is there a way to ensure our gestures have positive effects? Is there a way to effectively assess all these different situations and different people with different wants and needs and to discern what language operates the best in these dynamic moments? While these questions are large and challenging, the fact that there is a materiality to language should encourage us. Language can be observed, studied, and most of all, language can be changed. We can change how we employ language when teaching. In terms of this research, we can selectively adopt the language uses seen in both Leap Ahead and School #10’s facilities to collaborate on a classroom environment that encourages impassioned, present responses during lessons (School #10’s strength), self-reflection regarding one’s hurtful behavior and words (Leap Ahead’s strength), and egalitarian invitations to participate in discussion regardless of gender (School #10 and Leap Ahead’s weaknesses). As a result of examining and editing our uses of language (which requires being mindful of how different teachers in different sociopolitical and economic classrooms use language and to what effects), we can elevate the structural education and social education in both a suburban, accelerated program and a city, “catch up” classroom. With effort and attention, our use of language can transcend systemic economic limitations in a classroom, which is to say more simply, more effective pedagogy begins with the language we employ.