Communication, Leadership, and Organizational Skills in Emergency Response ()

1. Introduction

The contemporary environment introduces additional requirements for the efficiency and quality of the emergency response. While specific challenges, such as natural disasters, have been a significant force since the dawn of humanity, the changeable landscape of the 21st Century poses new, unprecedented challenges. In addition, rapid technological progress elevates the risks related to humanmade emergencies, whereas the threat of global and domestic terrorism has increased. Therefore, the exact characteristics of an effective emergency operations center serve as an area of intense interest for the professional community.

1.1. Background

Since the Second World War, emergency administration has concentrated mainly on emergency preparedness (Shawe & McAndrew, 2023) . Initially, this constituted planning and getting ready for an unexpected enemy assault; however, other stages of emergency management exist, such as alleviation, preparation, counteraction, and healing (Shawe & McAndrew, 2023) . Moreover, contemporary researchers distinguish specific aspects vital in ensuring the efficiency of the response. Effective communication, competent leadership, and strong organizational skills are the defining features of such a system. Consequently, a substantial body of knowledge reviewing said parameters in the discussed context exists.

1.2. Problem Statement

It has been established that emergency management as a discipline has yet to acquire the status of a fully-fledged professional area with well-established, comprehensive standards. Therefore, it appears attractive to investigate whether the professional research community has a consensus regarding the essential nature of the characteristics above (Feak & Swales, 2009) . Therefore, this paper aims to analyze the existing literature, synthesizing information on communication, leadership, and organizational skills in emergency response.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Communication

First, the effective functioning of an effective emergency operations center suggests the involvement of a broad array of individuals within certain professional groups. Therefore, the responders are expected to utilize their full potential, which is enabled through quality communication and optimization of efforts. Tipler et al. (2018) investigate the effectiveness of emergency response in the school environment, presenting a topical area of interest due to the increasing natural and humanmade occurrences observed in said environment. Irrespective of the specific emergency type, the synthesized hierarchy of critical actions is topped with effectively transmitting crucial information to stakeholders, i.e., communication. However, this study is descriptive, needing more evaluation parameters of Bloom’s taxonomy.

Simultaneously, interprofessional communication between response units has specific requirements (see Appendix A). Muniz-Rodriguez et al. (2020) analyze the issue deeper, offering a practical solution through extended social media use. While this approach utilizes the capacity of modern technology, its effectiveness reveals itself in communication with the public, and its suitability for interprofessional use remains uncertain. Wang et al. (2018) offer a more pointed investigation, outlining the primary emergency response communication requirements. As such, the tools are to demonstrate high levels of mobility and accessibility, which would make them sufficiently versatile to meet the criteria of various emergency scenarios. Indeed, the typical disaster response framework includes the command center and specific professional groups deployed on-site. Furthermore, the effectiveness of data-sharing can be attained if the main communication channel is accessible by all units and departments involved in the response protocol. This way, interprofessional links can be established, enabling the quick exchange of vital information and efficient distribution of assets.

2.2. Leadership

Correspondingly, communication alone does suffice to ensure the effectiveness of a diverse interprofessional response team. Consequently, the concept of competent leadership acquires additional importance in the case of emergency management (see Appendix B). When analyzing the rising threat of natural disasters induced by climate change, Zhou et al. (2018) emphasize the crucial status of emergency decision-making. The authors provide a comprehensive review of challenges faced by professionals, connecting each point to how competent leadership can enable better results.

The rapidity of an occurrence is the primary characteristic of an emergency, which dictates the necessity of efficient decision-making. Pranesh et al. (2017) added that competent leadership is dynamic, and emergency leaders should be able to adapt to any development within a single, changeable crisis. They evaluate the impact caused by the lack of said quality in the case of Macondo Well Blowout, applying theory to practical experience. Huntsman et al. (2021) demonstrate a similar stance, acknowledging the critical role of the adaptation potential of an emerging leader. Ultimately, these characteristics outline the particularities of the field.

While competent leadership is a dominant research topic across industries, the context of disaster response imposes unique requirements compared to other fields. Most crises are rapid, and the cost of untimely decisions is measured in human lives. Simultaneously, emergencies tend to develop quickly, and as the situation evolves, competent leaders should adjust their tactics in real-time. As a result, this requires a certain level of cognitive flexibility and substantial experience, which would consolidate the efforts of interprofessional team units most efficiently.

2.3. Organizational Skills

The aspects of emergency response are connected to another critical factor: developed organization skills (see Appendix C). Response teams are usually composed of various units, comprising multiple professional groups and volunteers. Ensuring a solid organizational structure will resolve the crisis efficiently is vital in such a complex environment. According to Hikono et al. (2018) , the purpose of the proper organization is to minimize the negative aspect of the human factor in disaster response, which was observed, for example, in the fallout of the 2011 Japan earthquake. The article convincingly evaluates the role of organizational skills in developing an adaptive structure capable of functioning in a stressful environment. Roud (2021) expands on this idea, stating that the progressive organization of a response team promotes collective improvisation, which, in turn, is a crucial instrument in the changeable context of a disaster. Shreshta and Pathranarakul (2018) point out the necessity of establishing a solid organizational framework encompassing all stages of the emergency response. The analysis reveals that their conceptual understanding is broader, as it extends beyond the on-site organization and involves the cooperative effort of all structures.

3. Conclusion

The current body of knowledge demonstrates the critical status of the discussed concepts in effective emergency management. While researchers analyze the significance of Communication, Leadership, and Organizational Skills individually in a detailed manner, it is unwise to view them as separate entities. Competent leadership is the basis of effective operations across many industries, but in the case of emergency management, its influence is immense, considering the stress and intensity of the context. During crises, strong leaders are expected to possess certain qualities that allow them to organize the response procedures optimally. Accordingly, organizational skills enable a flexible yet solid framework that adapts to the changeable scenario. Finally, a well-structured team with proper organization will have a better environment for effective communication. Therefore, Communication, Leadership, and Organizational Skills are three related concepts contributing to an emergency response’s positive outcome.

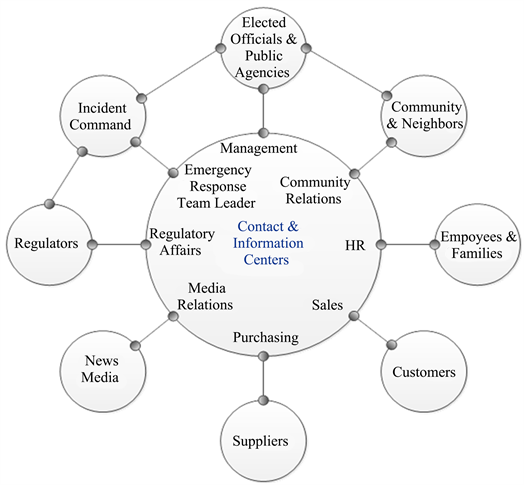

Appendix A: Crisis Communication Plan

Note. Adapted from Ready.gov. (2021, February 17)

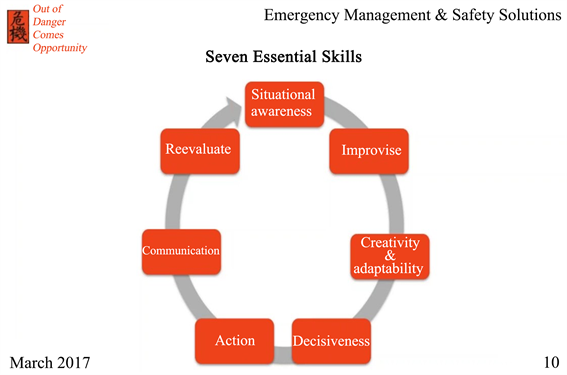

Appendix B: Leadership during Crisis

Note. Adapted from Phelps, R., & Clancy, S. (2017, April) . Leadership during Times of Crisis. www.youtube.com; Everbridge. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=49OcOk8E34U.

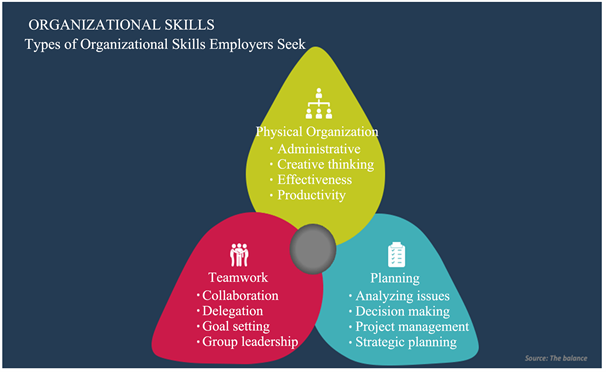

Appendix C: Organizational Skills

Note. Adapted from Organizational Skills (2022, September 13) . Professional PowerPoint Templates & Google Slides for Presentations. Collidu. https://www.collidu.com/presentation-organizational-skills