1. Introduction

Changes in methodology take place worldwide as issues related to the English language teaching become increasingly critical. We can no more reduce its significance to mere methodology because it is of great economic and social value due to the status and quality it gives to people’s lives which lets them operate at peak efficiency, better jobs, better salaries, better prospects are all at hand if you are proficient in English.

According to Jeremy Harmer (2013) , for instance, the users of the English language have long exceeded native speakers in number and although estimates vary, the ratio is 1:4, and this gap is widening all the time. In his book “The Practice of English Language Teaching”, he says: “In a few days I will be going to a large English teachers’ conference in USA which has the title ‘Tides and Change’. A couple of weeks after that it’s Poland and a weekend called ‘New Challenges for Language Teaching and Learning in the Changing World’; and then there’s a ‘changes’ conference somewhere else, and then it’s off to another country for a conference on…changes and how to deal with them! And as the year goes on- and who knows, through into the next year and the years after that there will continue to be meetings, seminars and articles about how to deal with the pace of newness and innovation in a world where increasingly sophisticated technology is only one manifestation of the way things just keep on moving and developing” (Harmer, 2013) . These are exciting times “as the English language has spread across the world as a global language, non-native speakers of English have come to outnumber its native speakers, which leads scholars, educators and policy-makers to rethink English language education, especially to reconsider the ways English is taught” (Fang et al., 2022) . Despite the economic problems, a range of innovations have been introduced in Georgia too. Various educational reforms try to offer something new, but all of them are based on a monolingual approach, and the attitude is so deeply ingrained that the topic is not likely to be discussed at local professional meetings, workshops and conferences. The unity of the policy seems to be based on increasingly dated ideas which hinder overall progress. More to the point, the interviews conducted all over Georgia reveal that local teachers of English see it as a matter of professional reputation, which is tarnished if they frankly express their views about ways of teaching English and support just a monolingual approach during conversations and only in interviews conducted anonymously do they tell their genuine preferences, confessing that they use bilingual approach at times, they regard it as beneficial and irreplaceable at specific moments and think it should be used as a resource. It is not just local practice, though. Leung and Valdes (2019) report on international experience in that direction, saying, “Before we enter into a detailed appreciation of the multi-faceted meaning of translanguaging in relation to language in education and language in society, perhaps it would be historically important to acknowledge that pedagogic value of making use of students’ community languages in the classroom has in fact been part of the debates in language education all along in the so-called ‘monolingual century’ in language teaching . It would be fair to say though, that some of the work in this area did not achieve high visibility”. It is significant to point out that local teachers are hardly familiar with the concept of translanguaging, which eliminates the chance of using it consciously and following the trends blindly becomes a norm. And the norm in Georgia is a monolingual approach, as mentioned above. A sharp delay in the development of productive skills in the target language is documented by the surveys and observations of different types.

Any manifestation of using L1 in teaching L2 is locally perceived as similar to the grammar-translation method, being unaware of the fact that these close associations are false based on the principles grammar-translation and translanguaging methods operate with.

Philipson (1992) identified five factors that are prevalent in foreign language teaching worldwide and that prevent teachers from creating bilingual classrooms:

1) Monolingual approach is a better way to study English.

2) Native-speaker teachers are better teachers.

3) The earlier you learn a foreign language, the better.

4) The more L2, the better result.

5) Using L1 in teaching L2 is detrimental, even if it is used for giving more transparent explanations.

Surveys show that local teachers adopt their professional ideas unconsciously, which originates from the following roots:

1) A firmly established tendency to monolingual norm (and careful revision is no longer regarded as necessary).

2) Close associations to the grammar-translation method when L1 is mentioned as a teaching resource.

3) Teachers tend to be reluctant to express themselves honestly for fear of losing jobs, professional reputation, etc. (generated from demands of local educational institutions which ask them to use just monolingual methods).

4) There is a blind acceptance of local trends and a lack of professional courage to present and test something dramatically new.

One fact always aroused my professional interest. As a teacher of English at university, I taught exam groups of B1 and B2 level students. During the course we could only use target language for discussions, but a bizarre invisible wall was felt, which was erected between the learner (as a whole person) and their learner-subself, as well as between their learner-subself and the topic in discussion. And when as an experiment, I would offer them to use L1 (and later, I helped them translate the content), their eyes started sparkling with a strange light as if they had been suffocated and now were allowed to escape becoming more active, lively, motivated and productive. It was apparent how it converted them to more task-oriented. Without it, I found it difficult to guess what they really wanted to say, how much they wanted to say, in which direction their thoughts led. So the limits were set by ourselves, walls built inadvertently. But the questions remained.

As reported by many studies, common underlying connections are proved to exist between languages. One of them is based on the fact which was revealed during the observations on students who arrived to study in America, that there was a close link between their overall academic success and their general competence in their native language (Baker, 2001; Cummins, 2001; Thomas & Collier, 2002) . Different authors describe this phenomenon in different words. Baker calls it a Common Operating System, there is also a Common Underlying Conceptual Base for expressing similar content (Kecskes & Papp, 2000) . There is also a Common Underlying Reservoir of Literacy Abilities (Genesee et al., 2006) , which derives from the idea that languages have a dynamic nature without any sharp boundaries between them (Cenoz & Gorter, 2017; Pennycook, 2017) and that setting boundaries between languages is a political act (Wei, 2018) .

The study of this issue leads to the term Translanguaging, which was introduced by Williams in the context of Welsh-English programs (Williams, 1994) and it has become increasingly popular among scholars working on bilingualism and the second language acquisition.

The advent of translanguaging has given rise to new perspectives in solving the problem and the multifunctional nature of pedagogical translanguaging allows us to provide it with a form of an EFL teaching method as “pedagogical translanguaging embraces a wide range of practices” (Cenoz & Gorter, 2022) and “translanguaging is a polysemic word nowadays and can be understood as an umbrella term that refers to a number of theoretical and practical proposals” (Cenoz & Gorter, 2020, 2021) .

2. Translanguaging and Cognitive Processes

As the research is conducted in the Georgian context, two requirements are identified, questing after the solutions: to prove the validity of the bilingual approach and to build a new framework for translanguaging as an EFL teaching method. The results will also be helpful to others with the same challenges. With that in mind, the following research questions are defined:

1) Should L1 be incorporated in teaching L2?

2) How should translanguaging as an EFL method be structured so that using L1 in teaching L2 means more L2 and not less?

The main theoretical framework of this study is based on constructivism which says that all new knowledge is based on old experiences and it is “an approach to learning that holds that people actively construct or make their own knowledge and that reality is determined by the experiences of the learner” (Elliot et al., 2000: p. 256) . Students’ interests, experiences, interactive learning and constructing knowledge are highly valued and considered to be the essential prerequisite to successful learning in classrooms where one of the main goals is to develop the skill of critical thinking generated from the theories of Piaget (1957) , Vygotsky (1978) , Bruner (1996) , etc. It is represented as the cycle of interdependent processes and is so natural that one is often unconscious of its effects.

Among many sets of thinking styles represented by scientists, Gestalt psychologists introduce productive and reproductive types of thinking (Wertheimer, 2020) . Productive thinking is using new approaches to solve problems creatively, whereas reproductive thinking is based on prior experience and association. It is noteworthy to mention that in both cases, mental activities are backed by experience if we take into account the fact that it is impossible to create anything new without relying on the background. So productive and reproductive thinking are similar to critical thinking, which involves the use of complex strategies and a range of cognitive abilities while interacting with information. In the context of EFL teaching, it ensures deep interaction with linguistic fabric that guarantees better acquisition of the target language. So this way, using L1 becomes a resource in teaching L2 and helps reveal learners’ genuine linguistic repertoire. The teaching process constructed around developing critical thinking means showing individual needs and meeting them means relatively rapid success in acquiring L2 because the teaching process is carried out with attention to individual requirements.

A range of studies confirms the existence of shared linguistic underlying connections. One of them is based on observations conducted on students who arrived in America for educational purposes. When their academic success and L1 competence were compared, the results showed an evident interdependence of the two components (Baker, 2001; Cummins, 2001; Thomas & Collier, 2002) . Researchers define it with different terms, Baker calls it Common Operating System. Also, there is Common Underlying Conceptual Base (Kecskes & Papp, 2000) . For Genesee et al. (2006) it is a Common Underlying reservoir of Literacy Abilities which indicates that languages have a dynamic nature without sharp boundaries between them (Cenoz & Gorter, 2017) and that “isolating languages creates a cognitive problem in the learning process because it excludes the possibility of benefitting from prior knowledge” (Cenoz & Gorter 2022) .

Exploring this issue takes us to the term translanguaging, which was first coined by Williams (1994) and described the practice of using languages alternately, using L1 and L2 (English and Welsh) one after the other, for example, learners read the text in English and discussed it in Welsh to better understand the content or the other way round. Williams said that translanguaging meant using one language to strengthen the other. To García (2009) , translanguaging is using languages as unitary meaning-making system of the speakers to select features for expressing ideas from the unitary linguistic repertoire. Definitions of translanguaging are almost similar to each other and see languages as one shared system where individuals navigate in search of meaning. Translanguaging is an increasingly popular term in linguistics, and the firm ideological basis is the main reason for its expansion. But for the most part, it exists in theories and not in practice in EFL classrooms, although it was meant for practical use from the outset. It is especially true about EFL classrooms because there is a gap in translanguaging literature which shows a lack of specific approaches, principles and features. Just general hints are given that translanguaging pedagogy can involve various activities for all four linguistic skills: reading, listening, speaking and writing: “Pedagogical translanguaging refers to the use of different planned strategies based on activating students’ resources from their whole linguistic repertoire” (Cenoz & Gorter, 2022) , “These practices have certain elements in common, they are planned by the teacher, and resources from the learners’ multilingual and multimodal repertoires are activated so as to enhance the development of multilingual competence” (Cenoz & Gorter, 2022) . But how to activate those resources? That’s the question. “With the focus on activating students’ multilingual and multimodal repertoires, pedagogical translanguaging plays a key role in facilitating learning” (Fang et al., 2022) . It is crucial to create an updated framework for translanguaging as an EFL method because, as reported by Wei (2022a) , “first, despite repeated attempts by some to brush it off as nothing different or new, translanguaging shows no sign of losing any discourse space. Then, there is the frustration of those who like the term ‘translanguaging’ but see it as primarily a descriptive label for language mixing practices. They feel that the leading proponents of translanguaging have failed to offer any precise method” and that “advocates of translanguaging pedagogies have failed to show convincing evidence that the pupils learn the target language better in second or foreign language classes if they are allowed to use more of their L1s” (Wei, 2022b) .

Colin Baker (2011) presents four main functions for translanguaging:

1) Helps deeper perception of information.

2) Helps the development of a weaker language (the target language).

3) Facilitates communication between school and home.

4) Builds unity between fluent speakers and language learners.

García and Kleifgen (2020) considered the use of L1 an essential prerequisite forming coordinated bilingualism, but the specific methodological principles have not been introduced so far. Lucas and Katz (1994) point out the effectiveness of pedagogical translanguaging and say that it should be used even if teachers don’t know the learners’ L1, that it is possible for group work or written tasks where compositions will be written in L1 and later translated.

One of the main objectives of pedagogical translanguaging is meaning construction which allows students to practice their creative thinking and acquire the target language structure through navigating L2 content with the help of L1 in search of building a unified whole. In that respect, the bilingual approach in EFL teaching is more beneficial than the monolingual one, not to mention some of the specific features. Taking into account that language is a social phenomenon, languages are learned for social reasons, to communicate, to deal with challenges and to handle various situations, the ultimate goal of mastering the language is gaining the ability to use it in unplanned situations, operate flexibly which is limited if the learner was given just monolingual EFL training with limited monolingual resources and limited linguistic repertoire which was based just on memorized phrases, learned lexis and structures and less acquired, less automatized because discovering learners’ natural linguistic repertoire requires incorporating L1 to reveal its genuine features. With regard to it, what is offered by monolingual methods is always limited. Furthermore, it limits learners’ way of thinking in the target language, puts the process into permanent artificial boundaries and attaches learners to it, gets them to stop thinking beyond it and makes them get used to the attitude that prevents overall development.

With that in mind, I find it beneficial to try to develop translanguaging competence in learners, which is possible if we convert the concept of translanguaging into a method in its complete form. It will help learners be protected from double monolingualism and eliminate the state of mind where two languages exist independently, constantly interrupting each other.

There are studies according to which bilingual dictionaries are more efficient for target language vocabulary acquisition than monolingual ones (Luppescu & Day, 1993; Prince, 1996; Laufer & Kimmel, 1997) because using translation is habitual to children and adults. Findings reveal that students who constantly used translation had better results in the USA, which gave rise to new perceptions:

1) The use of translation promotes general literacy.

2) Translation helps to learn a foreign language (Orellana et al., 2003; Manyak, 2004) .

Allowing students to use all their linguistic repertoire prevents them from setting artificial boundaries to operating in L2, but the borders of using L1 have to be defined from the outset because incorporating L1 in teaching L2 is characterized by ambivalence.

One of the main obstacles in that direction is the profoundly ingrained dominance of the monolingual approach in academic circles, especially in Georgia. The monolingual approach is associated with a sign of excellence and quality, and that is the norm that comes from educational institutions, which in turn exerts a more profound impact on teachers who go with the flow. In many countries bilingual approach is still perceived as a deviation from the norm (Zavala, 2019; Rosiers, Lancker, & Delarue, 2018) . The monolingual approach is widely accepted as common sense, and the fact that current textbooks are meant for monolingual teaching indicates that the issue is not the subject to beneficial changes for the time being, despite the survey results which find L1 a helpful resource in acquiring L2 according to a range of questionnaires and outcome analyses (Slavin & Cheung, 2005; Purkarthofer & Mossakowski, 2011) .

Many researchers emphasize the need to create bilingual projects which can improve and promote students involvement, confidence and engagement, and empower teachers with ready-made recipes for fruitful lessons (Cenoz & Gorter, 2020; García, 2009; Turnbull, 2001; Auerbach, 1993) . However, Turnbull (2001) indicates the need to establish limits to using L1 to prevent teachers from the temptation of overusing it, especially those with deficient productive skills. We cannot disagree with Turnbull as the threat is real. That is why finding out the exact place for L1 in L2 classrooms is so vitally important.

Although we encounter translanguaging elements in many classrooms, still the unconscious use of it leads to a range of challenges that can be avoided if translanguaging becomes a well-structured EFL method. It will widen the scope, the area for its operation, open new perspectives for teachers and expand learners’ horizons, increasing their understanding and experience of L2.

3. Methodology

To answer the research questions, a quantitative method was used. The research design consisted of a face-to-face interview and a structured questionnaire. The participants in a face-to-face interview were 200 adult citizens of Georgia. They were selected according to age, not older than 30 (in appearance) because the age group in Georgia is believed to know English better as they were born in independent Georgia.

The participants in a structured questionnaire were 200 teachers of English and 200 students of universities from across Georgia (9 universities in all). The limitation of the study is the lack of teaching experiments, as my university turned it down, stating that the educational policy was to use only the monolingual communicative method and no other methods were in consideration to be tested.

4. Procedure

The face-to-face interview was researcher-administered with two observers who wrote down the results. The aim was to find out the level of general communicative skills in English of adult Georgian citizens according to 5 features: problems in fluency, problems in accuracy, issues in both, no problems and abstention. I pretended to be a foreigner and asked 200 participants two questions:

1) Can you tell me the way to the nearest metro station?

2) Can you tell me something about this place?

As for the questionnaires, there were 20 close-ended questions put to the participants, which included their experience and preferences.

5. Data Analysis

The survey data is as follows:

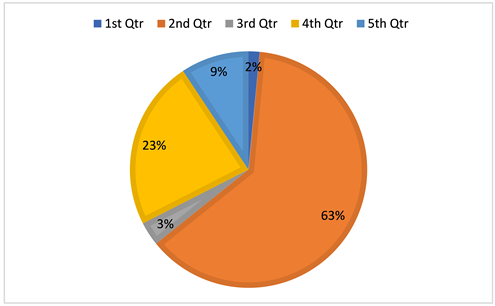

The diagram shows that 63% of the participants revealed problems in both, 23%—problems in accuracy, 9%—problems in fluency, 3%—no problems at all and 2%—abstained from answering. As it is apparent from the data, despite the dominance of monolingual methods used in teaching, the majority of English speakers in Georgia have problems with fluency, as well as accuracy, answering quite simple questions unexpectedly and the second majority is challenged with accuracy, which is the most crucial feature in communication to express and transfer meaning. 98% revealed a knowledge of English, which is good but only 3% were without problems.

Here are the most critical data that was obtained from the questionnaires. The results are displayed in the table:

Answer to Question 1: The main challenge is acquiring speaking skill

A to Q2: The target language learning goal is to develop speaking skill

A to Q3: Lack of satisfaction with the results

A to Q4: The main reason for unsatisfactory results is a lack of learner motivation and laziness

A to Q5: L1 is used in the teaching/learning process

A to Q6: Target language vocabulary is learned better if translation is provided

A to Q7: Grammar structures are understood better if a translation is used in controlled practice

A to Q8: Functions vocabulary is learned better if a translation is provided

A to Q9: The most popular activity is group-discussion

A to Q10: The most helpful method is a task-based method

A to Q11: The most frequent way out to linguistic competence is by translating

A to Q12: The most helpful tool to acquire new material is repetition

When interpreting the results, incorporating L1 in teaching L2 seems beneficial and acceptable for both sides: teachers and learners. Despite the dominance of the monolingual approach, both sides see the value of using L1 and do so but without any structure. The discontent with the results is high, but when asked about the reasons for that, the answers seem to be unconscious, stating that lack of motivation and laziness are at fault, but it must be noted that motivation is something to be triggered after engaging activities are under way and activities become engaging when there is hope the goal is achievable. This way monolingual way of teaching or unstructured, intermittent use of L1 poses a challenge for them that they cannot tackle because they are unaware of the core problem, they lack a clear understanding of its origin.

6. Findings

Discussing the results in detail made it possible to answer the research questions:

1) Should L1 be incorporated in teaching L2?—It is advisable for teachers to use L1 in teaching L2.

2) How should translanguaging as an EFL method be structured so that using L1 in teaching L2 means more L2 and not less?—Translanguaging as an EFL method should have a new framework that is based on the Communicative method, Audio lingual method, Lexical approach, Task-based teaching and Dogme, taking into account the specific features each of them have and the specific features which have a positive value in teacher/learner experiences and preferences. The beneficial details should be kept and regarded as components of the new translanguaging method. One such component can be found in the audio-lingual method because there is a close connection between speaking and cognitive processes which helps conscious and subconscious analysis of linguistic structures occur and speeds up languaging acquisition, contributing to installing the general fabric of language in the mind. The new form should be constructed in a bilingual way and lexis, which is collected through a bilingual lexical approach, should be processed thoroughly. For some, it may resemble meditation, engaging in mental exercise to reach conscious awareness of the material. The bilingual Dogme component is meant to expand the horizon of learners, at the same time they operate linguistically during lessons, allowing them to reveal their full linguistic repertoire through generating authentic topics through a high level of personalization where L1 is represented to discover the desired content.

The bilingual lexical approach is chosen because it is focused on providing learners with some ready chunks, which are easy to automatize and do not need extra time and effort and also prevent learners from L1 influence (as they do not have to translate sentences/phrases on their own).

It is essential to offer learners sentence frames that facilitate language acquisition, especially for weak learners. Also, language grading is something to be taken into account. Speak slowly to them, let them perceive the structure, let them translate and call on all their courage. If they are deprived of this, they tend to get disappointed and stop developing (Matthieu, 2022) .

Firstly, it is crucial to determine the exact place of L1 in the L2 classrom as using L1 carries an ambivalent meaning in such a context. Uncontrolled use of L1 can harm learners’ interests and make their efforts unsuccessful. In terms of this, three areas can be identified for the inclusion of L1 in L2 teaching:

a) where learners are allowed to reveal their full linguistic repertoire ( eliciting stage, discussions, etc.)

b) where there is a comparison of language forms to determine the correlation between them.

c) where it is indispensable to clarify the meaning.

Unsystematic use of L1 in L2 teaching is harmful and not desirable.

The main principles for the updated translanguaging method:

1) L1 is used as a bridge. The main focus is on the target language.

2) The lessons are student-centered, with a primary focus on individual needs.

3) The teacher is not a passive observer but rather one of the participants in the learning process, which can ensure better engagement and avoidance of the product created by only active students.

4) The focus is on productive skills.

5) The framework is based on the Communicative method, Audio-lingual method, Lexical approach, Task-based method and Dogme.

6) Grammar rules are learned inductively, the material is selected according to the context.

7) The content is as authentic and personalized as possible.

8) Particular attention is paid to enhancing critical thinking and the lexis generated from it.

9) Creating equal conditions for all students regardless of language competence or psychological characteristics (active, passive, lazy, shy, etc.)

10) Creating a close connection between the classroom and the natural world.

11) The purpose of homework is not just a revision of class material but generating new gaps and finding out actual challenges which would never be apparent during class work.

These principles represent the scope of the updated framework of the translanguaging method and provide assistance to teachers to solve any particular issue, whether it is a skills lesson or a systems lesson.

Taking a closer look at translanguaging as an updated EFL teaching method, it is more like a mixed method—a combination, synthesis of monolingual and bilingual approaches than just bilingual one, where using L1 in teaching L2 means more L2, which defies all logic but if according to constructivism (e.g., theories of Piaget) linguistic development is primarily conditioned by cognitive development of a learner, then incorporating L1 in teaching L2 seems to be beneficial as L1 is the best platform that can provide better opportunities for discovering deeper content.

However, it is noteworthy that from the three basic learning theories that have been historically known—behaviorism, cognitivism and constructivism, translanguaging method shares some features from each of them, which represents an interesting tandem, because these theories can be merged as a unified whole of all findings. It should be pointed out that the components that the updated translanguaging method comprise are neither new nor unfamiliar but are expected to be a highly efficient unity that is new itself in its form.

As for individual activities, as mentioned above, they should be based on five methods which have been selected as the basis, but one of them should be mentioned. Journal writing is an excellent component that can provide all features that meet the requirements of the translanguaging method. It seems to be particularly productive for revealing repertoire, involuntary memorizing, latent learning, activating passive knowledge, increasing learner autonomy, introducing a high level of personalization and defeating language anxiety. Journal writing can be varied by offering a question bank to learners as a scaffold. The question bank can be based on new material, direct and indirect hints or general topics to be answered according to their preference. The list of questions can be endless and the chosen ones should be answered in L1 at first and later translated into L2, the challenges discussed with a teacher during the lesson which generates some authentic material. Questions must be optional and not mandatory to generate true passion for the process and make it manageable.

Development of written speech can have a significant positive influence on oral speech development because, as Chomsky says “language is a tool for thought”, and if learners use language while they think to form an opinion and then write and get better at it gradually, then they get better at speaking too. Building from Thornbury’s three-stage model (Thornbury, 2008) , which consists of conceptualization, formulation and articulation when speakers observe themselves, the third stage can be replaced by creating written text instead of articulation and used as a way of practicing both: speaking and writing. Jeremy Harmer also sees close connections between them (Harmer, 2015) when he says that these two systems are not different but different variations of one system and that learners are better at memorizing things if we ask them to think about the material.

In that respect, journal writing seems to be worth implementing as one of the major activities of the updated translanguaging method, which gives the opportunity to break borders between languages, tactically, strategically reveal and activate learners’ repertoire by bringing up the topics, raising the questions and discovering the content which has individual value. It opens the way to creativity, which makes lessons more meaningful, attractive and interesting. People generally enjoy expressing their ideas which gets them confident and involves even the weakest and most demotivated learners into the learning process. This way learners create learning resources themselves that present their real needs and are better grasped. It is precious because the translanguaging method is student-oriented and involving them into producing material contributes to establishing authentic classrooms. It brings in a dogme element. One small episode can launch a new line of thought which leads to new depths and results in better self-esteem. Now learners are content with themselves not just as learners but as human beings, which has a broader meaning because it is the feature that makes them be always in a hurry to the lesson. Journal writing also helps establish a close connection between daily work and the ultimate goal of being able to speak fluently about any topic and the feeling increases the motivation, which is vitally important to succeed. An unpredictable environment adds zest to the situation and fills the hearts and minds of learners with enthusiasm. This way linguistic challenges are purposefully depleted.

Some students will want to share their ideas with the group, the rest will ask questions or discuss the issues in groups or pairs. It can become a new line which was the case when I started to use it in two of my groups at university, first as a freer practice and later as a homework which became the favourite part of a lesson for them. We would discuss the entries during classes and it was apparent how it motivated them, helped them gain a sense of accomplishment and confidence. The content was always attractive because it was authentic and helped me as a teacher to be aware of their needs, dispelled boredom, improved the rapport and sparked our interest—an absolutely necessary component for both sides.

Teachers try their best to help learners achieve their goals but there is no better way to do it than to be provided with material tailored to their needs from learners themselves. Teachers can better define “how”, but learners-“what”.

At the end of the term learners can do various projects based on what they have written in groups, pairs or individually.

Building from Thornbury (2009) , English classrooms need something like a rescue plan, return to classrooms free of learning materials and technologies where language emerges between teachers and students and Harmer (2013) says about journal writing that it is a good way to generate a dialogue between teachers and learners.

7. Conclusion

The article addresses the EFL teaching context in one of the post soviet countries, Georgia, the advantages of the bilingual approach, translanguaging as an EFL teaching method and its potentiality. As reported by the article, translanguaging is a likely candidate for becoming one of the most perfect methods because, along with narrow professional goals, it enhances the personal development of learners. Having taken all the above into account, rather than viewing translation as detrimental to the development of communicative skills, it should be regarded as rewarding and beneficial.

Analyses of the findings show that the monolingual approach in EFL teaching does not meet the requirements of learners in terms of practical needs and teachers and learners tend to use L1 as they feel the strategic value of it but find it challenging because unstructured use of L1 can have an undesirable washback effect as well. Following that, a new organized framework is offered to tackle the problem which is based on the components of five EFL methods: Communicative method, Audio-lingual method, Task-based teaching, Lexical approach and Dogme.

The limitation of this study is that it lacks findings from teaching experiment as the offer was turned down by my university with a rather unsatisfactory reason that the usual practice and the only acceptable way of teaching is a monolingual standard.

Finally, it should be noted that post soviet countries like Georgia need more professional support with regard to its academic development in the field of EFL teaching. As Leung and Valdes (2019) say, “The notion of translanguaging is both challenging and exciting; challenging because it forces us to examine our previous perspectives on language itself, and exciting because it suggests new possibilities and outcomes for the teaching and learning of additional languages” and in terms of that translanguaging with its updated framework seems to be a convenient tool to solve problems related to communicative competence in the target language.