Communications on History. Building Identity and “Making Sense of History” in the History Course—A Matrix for Empowering Historical Thinking ()

1. Introduction

In view of the enormous quantity and the wide range in quality of historical narratives which are offered via audio-visual media, internet, TV, social media, political debate or propaganda, history education at school and at university is challenged to develop adequate forms of historical learning. These forms of learning should allow the students to unfold their analytic, descriptive, comparative and narrative competences and should hone students’ skills in critically assessing the quality of the multiple historical narratives.

As a goal for future debate and research in history didactics2, we can say that the accelerated cultural change enforced by the digital revolution requires a meta-theory of historical learning which is viable in the transnational, intercultural discourse. In equal measure, it requires innovative conception and design of the praxis of historical learning in the history course and/or the history classroom. Innovative theory and praxis is likewise needed as regards perception of the communication between the teacher and the students in a history course.

The rapid shift to online-learning caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in spring 2020 forced thousands of university teachers3 and secondary school teachers to engage in urgently adapting themselves to new or additional forms of eLearning, video-teaching, live-streaming of lectures and digital assessment.

These new developments in knowledge management and personal development of the academic world and the world of education require more than adequate management and decision-making at the institutional level. They require innovative forms of education and training in terms of the performative, social and communicative competences of the academic staff, the teachers and the trainers of the young academics and teacher trainees.

However, when exploring existing theory to describe, observe and evaluate such processes of competence building in the communication of the history class or the history course, only a few models have surfaced so far for describing the communicative process of historical learning.

This paper exemplifies the theory that underlines the practical model of competence-building in communication of the history course, namely the “process-oriented concept of history didactics” (Ecker, 1992, 1997b, 2015, 2018b, 2020).

In this concept, we assume for the situation of history teacher education, that an analytic, comparative and process-oriented approach to historical learning supports the students in acquiring the skills needed for relating their individual historical thinking to professional historical methodology in such a way that they can develop a “critical approach” to the given historical narrations, and that they can build up their identity by “making sense of history” (Rüsen, 1994: 74ff; Rüsen, 2006: 40ff) via historical enquiry and narrative-building all on their own.

The learning group was thus introduced as a “social system” in the early 1990s (Ecker, 1992). Additional elements of the process-oriented concept were implemented with the linguistic turn. The narrative approach—as discussed in the early 1990s in history didactics—was one of the turning points for the understanding of historical learning (Ankersmit & Kellner, 1995).

Empirical studies on historical learning in the history classroom have broadened significantly in the following two decades (e.g. Lee & Ashby, 2000; Epstein & Peck, 2018; Ercikan & Seixas, 2015; Van Boxtel & Van Drie, 2018; Van Drie & Van Boxtel, 2007; Van Sledrigh & Reddy, 2014; Van Straaten, Wilschut, & Oostdam, 2016), however the communicative paradigm was not that much elaborated in the context of history didactics. For an overview of research interests in the various national educational contexts compare Köster, Thünemann & Zülsdorf-Kersting (2019), for the thematic approaches see the recently published handbooks (Carretero, Berger, & Grever, 2017; Metzger & McArthur Harris, 2018). More attention to a theoretical framework for social system of historical learning has only recently been extended within the German speaking community (Zülsdorf-Kersting, 2018). For an overview on “current empirical research literature on the education of history teachers” see Van Hover & Hicks (2018: 391ff).

As history educators we are aware that history education in school was—and in many countries still is strongly influenced by national educational policy (Ecker, 2018a: 1599; Carretero & Perez-Manjarrez, 2019: 71; Grever, 2012), that the “history wars” by school education (Macintyre & Clark, 2003; Carretero, 2017) are ongoing and that there is actually in many countries of the world a growing tendency to put again more emphasis on national, or even nationalistic history.—However, our goal in teacher education is to work for a democratic and pluralistic society, which includes, in our understanding, the possibility to work upon and discuss the controversial interests—in history as well as in present societies. This is why we enforce the analytical, critical and genetic approaches to historical thinking.

2. Building Identity and Making Sense of History in the Narrative Approach

As a reaction to strong tendencies of nationalistic education during NS-dictatorship and fascism, post-WWII history education in Austria as well as in many other European countries was explicitly conceptualized to foster an anti-fascist, pluralist, and democratic form of history education. Within the framework of the European Cultural convention, which was put into force by the Council of Europe in December 1954, many European countries have revised the history curricula and history textbooks in the first decades after WWII with regard to bias, prejudice and nationalistic stereotypes (Council of Europe, 1995; Jeismann, 1984; Lemberger & Seibt, 1980; Hofmeister-Hunger & Riemenschneider, 1989; Deutsch-Polnische Schulbuchkommission, 1995; Pingel, 1995; Maier, 2004).

Especially in those countries where history is taught in combination with subject “citizenship education” and/or with subject “social studies”, history education has progressively strengthened the ideal of the historically thinking student/teacher who acts as a responsible citizen of democratic societies (Ecker 2017, 2018a; Kühberger, 2017; Bergmann et al., 1979; Ankersmit, 2002; Cajani & Ross, 2007; Stevick & Levinson, 2007; Stradling & Row, 2009; Reid, Gill, & Sears, 2010; Arthur & Cremin, 2012; Davies, 2017; Carretero, Berger, & Grever, 2017).

![]()

The proposed balance between past, present and future, stimulates the opportunity to include the reflections on expectations for the future in this kind of historical thinking. Following the narrative approach to history as developed by Danto (1965, 2007), Rüsen (1979, 2005) and Ankersmit (2001), the way of future-oriented thinking is a constitutive element of every historical concept. It is this broader focus on history which opens up the pathway to historical-political reflection as well as to identity-building (Berger, 2022) and to the process of “making sense of the past” (Rüsen, 2006: 1), as well as to the process of “making sense of history” (Rüsen, 2006: 40ff), respectively.

In the narrative approach, “history” is regarded not as a fixed or substantive entity of the past, but as a dynamic construct of the present which is open to future interpretation, reasoning and debate. Furthermore, although based on sophisticated methodology and professional investigation, “history” is nevertheless grounded in the living environment, ergo, the daily praxis of human beings4. Rüsen assumes that the fundamental way of thinking about ourselves is to “make sense of the past” by “interpreting the past for the sake of understanding the present and anticipating the future”. This approach to history represents, as Rüsen says, a central function of dealing with history, i.e. obtaining orientation for future action.

This link between past, presence and expected future is widely accepted in the German speaking community of history didactics (Jeismann, 1988) but gets growing acceptance also in other communities of history didactics (Seixas, 2017). The narrative approach serves as the basis for various conceptions of historical learning. Moreover, curricula, syllabi, and proposals for history didactics in the classroom aim at supporting the development of historical sense-making of the reflecting and self-reflecting “social subject” (see below, chapter 5).

When relating this educational means of historical learning to teacher education and to the concept of “historical consciousness” (Stearns, Seixas, & Wineburg, 2000; Seixas, 2004) in this context, we can say that we as teacher educators regard the students in the history course as “human beings, who are immersed in history and encounter the historicity of humanity” (Koselleck, 1979).5

More recently, this approach to historicity of humanity has been described by Rüsen as “making sense of history” (Rüsen, 2020). Entering in this approach to the past requires also from student teachers high capacity in self-observation and self-organisation. The empowerment of the history teacher trainees in developing their capacity for self-observation and self-reflection, therefore, remains one of the predominant goals for history teachers’ education of our time.

My approach to historical learning in the process-oriented model corresponds to the idea of identity-building by evaluating one’s own experience over the course of time and—in relation to the analysis of the present situation and the expectations for the future—assigns the personal role (place, position) in society in relation to the debates in the history course on the one hand, and with critical analysis of the given historical narratives on the other hand.

In teacher education courses we therefore work not only on narratives of political history but in equal parts on narratives of social history, economic history and every-day-history/cultural history. All of these aspects are represented also in the curricula of school and teacher education.

Albeit, with regard to the actual dynamics of societal and cultural change, the personal capacity for dealing adequately with this “historicity” is highly challenged. Kansteiner (2007: 30) and more recently Seixas (2017: 60) posed the question of whether this conception of a “historical consciousness” of the man of modernity is still an adequate key-concept in the dynamic of the digital revolution. We could add for historical learning, that this digital revolution is characterized by historical narratives that are immersed in the anonymous, utopian and/or virtual space of the sense-producing dynamics of the functionally differentiated multicultural society, the members of which attempt to sketch—and to frame—by all manner of arts, crafts, performances and expression, often without being any more identified with their creation as individual authors.

The questions of Kansteiner and Seixas are part of the actual debate in the philosophy of history respectively in theory building of history didactics.—Although, for the time being, the conceptions of historical thinking in the narrative approach as developed by Danto, Rüsen and Ankersmit are still relevant for theory building in history didactics. For the near future we can imagine the communicative approach to historical thinking, as described in the following, as an equivalent and adequate concept to describe historical thinking in the digital age.—Albeit, first and foremost, we need a model which operationalizes and exemplifies the narrative approach in history for the concrete communications between teachers and students in the history course.

3. The Communicative Approach to Historical Thinking

Together with a group of dedicated teacher educators in subject “history” and “citizenship education”, for the purpose of teacher education at universities and pedagogical universities, I have developed a model for the theoretical reflection of learning processes in the history course6. The model has been discussed since the early 1990ies as the “model of process-oriented history didactics” (Ecker 1992, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997a, 1997b, 1998, 2015, 2018b).

The innovation for “historical learning” coming from the “process-oriented model of history didactics” is marked by the epistemological shift in the perception, description and analysis of the history course: Historical education in this model is not any more regarded as an instruction of prefabricated historical narratives, but as a form of communication on history between teacher(s) and students, and thus a co-construction of historical narratives in the learning group.

Behind this assumption of “historical learning as a communicative process” lies the conviction that school and university education are still largely built on ritualised forms of learning which tend to hinder rather than foster cognition and insight into complex situations7. Future-oriented historical education, however, demands co-ordinated, integrative and process-oriented forms of learning which facilitate the connection of knowledge and insight, of content and social process. It needs forms of learning which transcend the treatment of specialist knowledge as a kind of mental challenge but make that knowledge real in terms of concrete social competence.

Looking for theoretical support in developing the process-oriented model for teacher education we were not able to turn to traditional pedagogy: classical educational theory is based on the dyadic model of "the teacher" and "the pupil". Now it has of course been a fact for the last two hundred years or so that teaching at schools and universities happens in larger groups: one teacher practically always meets several pupils. In our theory building we have therefore taken on board ideas and recent insights from fields such as group dynamics and group pedagogy, social psychology and social systems theory8.

In this approach, my theoretical interest is in line with those didacticians, who aim at developing an understanding of pedagogy and didactics as disciplines of social sciences. The central idea of this approach isto acknowledge the learning and teaching situation as a social structure in its own right. In terms of its application this means that any training course geared towards learner independence can be successful only if the process of training itself is viewed and treated as an independent social structure.

In this understanding it is evident that the social dynamics taking place in the teaching situation itself has to be recognised as being part of the thematic learning process.—and it has to be made explicit in the design of the course in order to be useful for further learning. Any insights gained from the explicit observation of social processes must then feed into the planning of the next thematic learning phase.

For the didactics of history this means the awareness, which has to be kept alive at all times, that the learning and teaching situation in the history course is a dynamic social structure. Only if the teaching in the learning group is organised in a dynamic way can it engender learning which produces insight into historical processes, where the learners can negotiate on historical narratives and reflect on the social/political situations they are living in themselves, and which are a product of a concrete historical development.

Apart from the process-oriented concept (Ecker, 1997a, 2015), first ideas on the theoretical basement of the construction of historical narratives in a communicative process can be found in the theoretical reflections on historical learning of Jörn Rüsen: “the self-reference of individuals or groups… is never emerging isolated from one self, it is always expressed in interaction with others—narration is always a communicative process” (Rüsen, 2008: 88).

Although Rüsen develops his idea of “historical learning” within the paradigm of narratology (see above), he derives the concept of historical narration from the daily practice of human beings. The development of “historical consciousness” is in this sense conceptualized as a social construction. That is, it develops in the “here and now” of communication with others: “historical narration is a communicative act of making sense of experience [over the course] of time. Its necessity results from human life praxis which provides the experience of permanent pressure of change over time; this experience has to be worked through by the persons affected in a communicative process, which empowers them to find sensible orientation for their activities, especially when they perform in social interaction. Hence, the origin of historical consciousness of human beings emerges from the experience in the presence…” (2008: 75).

Meanwhile, historical consciousness, which is constituted in the here and now of communication and interaction, goes beyond the idea of the individual person who processes historical knowledge and generates “historical consciousness” through this mental process. Rather, the development of historical consciousness in the communicative process can be described as a co-construction emerging in the interaction between the social subjects (see below, chapter 5) involved in this communication. That is, the social subjects interpret the present situation by negotiating interpretations of existing historical narratives, by bringing in diverse individual experiences, and also by relating the debate to their actual interests. By relating historical analysis to actual interests, the social subjects create sense for their present situation and acquire scope for future actions.

Although it is a guided form of communication, the situation in general as a form of communication about the past in the “here and now” also holds for the history course. (In particular as concerns the university course where teacher trainers communicate with students who are already responsible citizens and thus expected to articulate their interests). We therefore can assume: Historical consciousness in the communicative situation of the history course develops in a social process as a dynamic construct, characterized by analysis and interpretation of and negotiation(s) about historical narration(s).

For the didactic situation in the history course, we assume that this is also the way of historical thinking in the target groups of historical education—at least, as far as such education is conceptualized to allow and involve the interests (questions, curiosity, arguments…) of the students. That is, the students in communication and collaboration with the teacher interpret the present situation by negotiation, critical analysis, and interpretation of existing historical narratives, by bringing in diverse individual experiences, and also by relating the debate to their actual interests as well as to their own historical investigations.—As far as this is the case, we can now ask for history didactics:

· How can we link the narrative approach to the “here and now” in the communications on history in the history course?

· How can we describe (and hence investigate) the processes of communication in the social system of historical learning of a history course?

4. History Didactics as a Social Science

An early conception in the German speaking community understood the emerging new discipline of history didactics as “a social science”, where this social science was regarded as “embedded in the living environment of human beings” and to be brought into rational operation by a process of “reflecting and self-reflecting [on the part of the] researcher, who generates his research questions in relation to this living environment” (Bergmann, 1980: 24f).

The idea of conceptualizing the historian as a “social scientist” seemed obvious in the 1980ies, especially for the emerging new dimensions of historiography such as economic and social history, gender history, the new cultural history or the post-colonial studies. Even more could the idea be applied, as Bergmann proposed, for the dimensions of history didactics and historical education: The history teachers were expected to develop the students’ ability for thinking historically and reflecting upon their role as responsible and critical citizens in democratic societies. In this sense it seemed likely to understand the teacher as a particular type of social scientist who explored in his daily praxis the progress of historical learning in the target group in a kind of field research, i.e. an investigation in the social field of the history classroom9.

Looking back on forty years of the discipline, it seems as if this conception of history didactics has not been frequently applied to the social situation of learning and teaching history in the classroom. Nevertheless, the idea of understanding history didactics as an “applied social science” (Ecker, 1997a: 400f) features high potential in terms of both empirical research on and the theoretical reflection of learning processes in the history class/course.

Taking the assumption of Klaus Bergmann and relating it to the social systems theory of Niklas Luhmann (1984), we can 1) understand the history teacher in the history course as a reflecting and self-reflecting researcher in the “social system” of historical learning, and 2) understand the history course as a social system, i.e. a system of communications about history in its own right (Ecker, 1992: 3).

As already mentioned above, when applying this idea of a social system to education in the history course, it states that the “(participant) social subject” analyses, invests, adopts, negotiates, reflects and decides upon historical accounts and historical narratives in a process of co-construction with other “social subjects”. Nevertheless, this idea needs to be further developed in its various epistemological and methodological dimensions.

What would be needed (ad 1) for the daily practice of teaching is for the teacher to disclose his/her assumptions on and goals with historical learning, and for him/her to begin to describe, reflect upon and evaluate the processes of historical learning and relate his/her observation, analysis and reflection more systematically to the concrete communications of and with the students. What would be needed (ad 2) for the shaping of the perception of the students is that they see themselves in this daily practice of learning about history as “participant social subjects” who bring their specific view, experiences and interpretations about history into the discussion.

On the example of the Planungsmatrix, which will be described in detail below, chapter 7, I will propose a set of systematic questions for the teacher to be explicated when planning a history course/class. These questions could also be taken as part of an investigation, observation and/or evalutation of the learning/teaching process.

5. The History Course as a Social System

“The entire metaphor of possessing, having, giving and receiving, the entire “thing metaphoric” is unsuitable for understanding communication.”10

In this paper I use the sociological term “social subjects” (Emmerich & Scherr, 2016: 283) to describe the systemic function of persons involved in the communication of the social system. The “social subject” in the sense of social systems theory is understood as an interacting and communicating person who constitutes by this “communications” with other “social subjects”, as Luhmann (1984: 191ff) underlines, a self-referential social system—in our case the social system of “historical learning”. The social system of “historical learning” is thus constituted by communications throughout the history course. When applying this idea of a social system to education in the history course, it states that the “participant social subject” analysis, invests, adopts, negotiates, reflects and decides upon historical narratives in a process of co-construction with other “social subjects”.

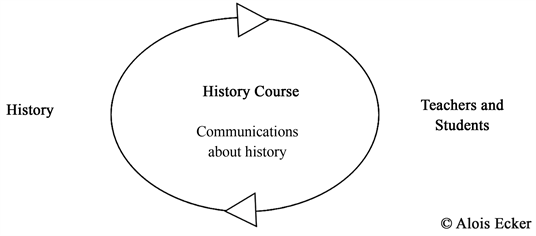

In the sense of the social systems theory (Luhmann, 1984: 191-240), both, teacher and students are regarded as “social subjects” who are part of the same social system of “historical learning”. This system of historical learning, as Luhmann would say, is constituted by communications about history: e.g. communications on the understanding and analysis of historical narratives, the contextualization and interpretation of historical sources, the comparison and negotiation of different perspectives and thus the discussion of possible variations of interpretation of a given piece of evidence (Image 1).

In order to engage in such communication and interaction in the history course, both, teachers and students are encouraged to acknowledge that they interact as distinct and self-referential persons who have their individual ways of generating meaning about past developments but nevertheless, by means of back-coupling/feedback, have the capacity to arrive at an intersubjective approach and a collaborated interpretation of the given evidence. To enter into such a debate and to maintain this kind of balanced, horizontal communication, self-confidence, a basic capacity for self-reflection (Habermas 1973: 204ff), and

Image 1. The systemic model of the history course.

critical and responsible thinking seems favourable and appropriate from both sides—that of the teachers and that of the students.

Considering the general conditions of communication within the current educational systems, a necessity has arisen for empowering both the teachers and the students to come to such interdependent, self-reflecting positions. As concerns teacher education, we can ask, what could be done during initial teacher education to make future history teachers more confident in going in this direction.

This was one of my central questions in teacher education at Vienna University, when I conceptualized the process-oriented model in the 1980s. The goal was to develop a holistic, integrative model of teacher education which was powerful enough to describe communication in the “here and now” of the history class/course.

The theoretical difficulties when trying to develop an adequate theory of competence building11 in the learning process of a concrete history course provoked the final cut with the monad of the “individual learner”. Luhmann’s theory of the social system with the idea of the social system being constituted by the communicative process was the missing link in my theory of historical learning. An essential element in Luhmann’s theory building was the assumption of the social system being an “autopoiëtic” or “self-referential system”. The assumption of autopoiesis of the social system includes the factor of “self-observation” as “the necessary component of autopoiëtic reproduction” (Luhmann, 1995: 37) in the social system. When adopting this assumption for the didactic situation we can now add, that on the thematic level social systems are constituted by communications about the topic, while on the elementary, operational level, they are “constituted by the production and processing of meaning.” (ibid.)12.

6. The Circular Model of Historical Learning

As described by Watzlawick et al. (2014: 12), communicative processes—and thus understanding of information given by “the other”, namely, the partners of communication—do not develop in a linear process of acquiring information and/or accumulating knowledge. This was the misunderstanding of educators and didacticians who relied on the taxonomy of Bloom (1956); see also Anderson & Krathwohl (2001)13.

In contrast to this linear conception and progress of learning, the systemic approach to communication enforces the idea that understanding in general, and learning, in particular, develops in a circular process. The circularity of understanding and learning reflects the dynamic processes of communication in daily-life conversation, whether this concerns the conversations in the family, at work, in peer-conversation or at school and university. Following the systemic approach learning and understanding develops as a co-construction of meaning in the process of communication and interaction with all the partners of communication involved.

A) General aspects of communication: the reduction of complexity

General aspects of communication show some particularities, which have to be solved on the level of theory as well as on the level of practical application. These particularities are about 1) the complexity of communicative situations, 2) the involvement of the researcher (teacher, student) in the process of communication, as e.g. described above, chapter four, 3) the dynamic of communicative processes, as described above, chapter three, or 4) the irreproducibility of communicative acts. The latter might be taken here as element of the conditio humana.

All four aspects are relevant when talking about communication in the history course. We take here the first aspect, the problem of “the reduction of complexity”, in order to exemplify some essential dimensions in the communication of historical learning: To come to viable descriptions of the processes of historical learning in the concrete history course—and to generate the possibility to describe, investigate, analyse and understand such processes—we have to reduce the complexity of communication without undue simplification.

In social systems theory, the complexity of communication has been identified as one of the crucial challenges to be solved. It is discussed under aspects such as the “relationship between system and environment” (Luhmann, 1995: 176pp), by aspects of “self-reference” (Luhmann, 1995: 437pp) and by the relationship of “double contingency” (Luhmann, 1995: 103pp).

1) The first reduction of complexity is that of “creating and maintaining a difference from the environment” (1995: 17) and to use the “boundaries of the system” to regulate this difference. Maintainance of boundaries is also system maintainance. In our case of the history course this means: By defining the boundary of the system of historical learning, the complexity of communications in e.g. a group of 25 students can be significantly reduced. The social system of “historical learning” consists (solely) of all communications within this group, which are dealing with “history”. On the contrary, communications dealing with language teaching, with sports, physics and other subjects, but also communications with students’ talks about recently consumed films, or with blogs in social media etc. are not part of the system of “historical learning”. They are part of the “environment” of the “historical learning system”.

Marking the boundary for communications dealing with history against the environment helps to reduce the complexity and to remain focused for both, the teacher trainer and his/her conception of the history course, and the (interests of the) students, who are involved in these communications on “history” and who aim at better understanding historical issues.

In other words: when teaching history, the teacher trainer is not working in course communications with regard to (all possible aspects of) all the persons, who are present in this concrete history course, but he/she establishes a communication with the (psychic systems of the) students, which is focused on aspects of history. This definition of the boundary of communications allows the teacher to ignore all other aspects, which she/he might perceive as being part of the students’ identities, but which are not part of the communications about history (e.g. their relationship to the parents, the brothers and sisters, the friends, their membership in football clubs, their religious affiliations, their membership in various social media platforms etc.).

2) The second reduction of complexity consists in maintaining a clear focus on the self-reference of the social system of “historical learning” in the group (!) of persons, who are communicating about history. This reduction is reasonable and necessary. The social system would clash within a few minutes when a teacher would try to maintain the communication with the individual (!) person as a whole, respectively with the [personal, psychic] self-reference of all the students, who are actually present in the classroom.

Such self-reference of the social system may consists in e.g. an agreement (!) among the group of teacher(s) and learners, about the topic of interest, about the questions to be elaborated and answered, about the choice of content and methods for working on the questions, about the strategies of communication and discussion, about the encouragement to relate the topic under discussion—if adequate—to the living environment of the students, about the transfer of knowledge and skills for working with historical sources on the next task etc. Curious questions of students may be integrated in this self-referential communication, but the dynamic of the group will bring to the fore within a few moments whether the questions might be interesting a/o representative for the other participants and thus contribute to deepening the historical knowledge and the historical consciousness of the learning system or whether they are identified by the group as going beyond the boundary of the system (and thus become subject of the environment).

3) The third reduction of complexity in systems theory deals with the problem of understanding and learning. In systems theory, the problem of understanding and learning was introduced under the theorem of “double contingency” (Luhmann, 1984: 148pp; Luhmann, 1995: 103pp). A person (ego) who enters in communication with another person (alter) cannot be sure, whether the partner(s) of communication understand(s) the information she gives in the form and the sense she would like it to be understood.

The transmission of information is contingent, the recipient of information (alter) selects from this information following inherent selective criteria of his psychic system, hence, the partner (ego) is incertain under which perspective(s) the information has been processed by the other partner (alter). As a consequence, one partner can never be sure, what the other partner observes, thinks, plans next etc. Each of the partners is a “black box” for the other as regards the personal self-reference. The complexity of such situation rules out that the participants fully understand each other. Understanding the other by communication remains uncertain and risks to fail.

The innovative step out of this epistemological dilemma was, to accept, that the phenomenon of “double contingency” exists on both sides of the relationship, and that social systems emerge “through (and only through) the fact that both partners [resp. all partners involved, AE] experience double contingency and that the indeterminability of such a situation for both [all, AE] partners in any activity that then takes place possesses significance for the formation of the structure.” (1995: 108)

The proposal for the reduction of this complexity, coming from systems theory simply is, to accept the “incalculability” of the relationship and concede to the partner(s) in the communication that they are free to interprete the given information following their self-reference:

“For the few aspects through which they deal with one another, their capacity for processing information suffice. They remain separate; they do not merge; they do not understand each other better than before. They concentrate on what they can observe as input and output in the other as a system in an envirionment and learn self-referentially in their own observer perspective. They can try to influence what they observe by their own action and can learn further from the feedback.” (1995: 110)

With reference to Watzlawick et al. (2014) and to aspects of organisational learning (Argyris & Schön, 1978, 1996; Argyris, 1999) I have been working further on the dimensions of the idea of “feedback” when conceptualizing the process-oriented model. In pedagogical conversation, the term “feedback” is frequently used to describe formative or summative evaluation at defined steps of or at the end of the learning process. Watzlawick et al. (2014: 11pp, 120pp, 138p) understand the term of “feedback” as “the secret of natural activity” of self-regulating systems (2014: 13)—In my understanding, the phenomena circumscribed here could be defined as the central allocative function of communication which is in permanent action as long as the communication is ongoing. To describe this allocative function of communication, which is of high importance for all questions of understanding and the correction of (miss-)understanding I prefer to use here the term “back-coupling”.

In consideration of the existing double contingency between the persons involved in the social system of historical learning, “Back-coupling” can be regarded as a function to open possible channels of communication between ego and alter

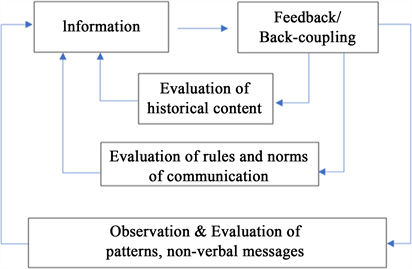

Image 2. The functions of Feedback/Back-coupling in the communicative process (© Alois Ecker).

for clarifying and evaluating information and understanding on different levels: 1) The level of (historical) content and the (historical) meaning of this information which is communicated by ego to alter. 2) The level of evaluation of rules and norms of communication of the system on both, the professional dimension (e.g. the implementation of subject specific categories, concepts and methodology …), and the socio-psychological dimension (e.g. the significance of influence/authority, the use of collaborative a/o constructive forms of dealing with the other …), 3) the level of observation and evaluation of patterns, non-verbal massages, aspects of coordination, decision-making and organisation of the system, which might not have been discussed and reflected regarding their relevance for the self-reference of the concrete social system of historical learning at hand. These forms of back-coupling, of clarification and evaluation of information work in an ongoing process while the communications within the social system are ongoing (Image 2).

B) The Seven Factors of the Circular Model of Historical Learning

For the purposes of coming up with an adequate and viable description of the communication process in the history course and for determining distinctive indicators for the observation, description, analysis and reflection of these complex communication processes in the history course, I have developed the following “circular model of historical learning” (Image 3).

The “circular model of historical learning” identifies seven factors which constitute the process of historical learning in the communications of a history course. Communication in the history course develops as a dynamic process of interaction between these seven factors. Each of these factors is understood to be interdependent to the six others. Specifically, these factors relate to questions about

· The addressee of communications, with emphasis on diversity, as well as the social and cultural context.

· The aims and rationales of communications with emphasis on the procedural concepts of historical thinking.

Image 3. The circular model of historical learning.

· The choice of the topic for communication, with emphasis on the substantive concepts.

· The structure(s) of communication(s), including organizational dimensions such as hierarchic, team-oriented or project-oriented forms of learning14.

· The processes of analysis, interpretation and methodological transfer as regards aspects of historical learning.

· The types of back-coupling, as a kind of self-reference of the learning social system.

· The types of reflection and self-reflection, with emphasis on identity-building and making sense of history on both the personal dimension and the social dimension.

All seven factors are regarded as dynamic and interdependent fields in the process of historical learning (Ecker, 2015).

The factors are relevant for all persons involved in the communicative process. They can be regarded from the perspective of the teacher who plans or steers the learning process, but are equally relevant for the student who contributes to the working process, asks questions, presents the results of group work, etc.

For our purposes of planning and designing the history course, we take the perspective of the teacher who plans the history course. He/she will ask questions such as:

1) Who are my addressees? What are their interests as concerns the (work, debate on the) topic? What information about the addressees is relevant for successful work on the topic?

2) What are my aims for this course? What is the rationale behind the design of the course? What aspects of historical thinking could best be elaborated with the example of the historical topic under discussion?

3) What topic could be chosen to reach this goal? What substantive historical concepts can be illustrated? What theme(s) emerge in the process of discussion?

4) What kind of communication would be appropriate for developing a learning process for working on this topic and for attaining the chosen goal? (e.g. presentation, team-based work, project work, case study?)

5) What forms of analysis, interpretation and (methodological) transfer could be chosen for further elaborating on the historical thinking concept under discussion?

6) What types of back-coupling are essential for maintaining a coherent communication process (at the cognitive, emotional, and affective levels)?

7) What types of reflection will be helpful for fostering identity-building at the personal and cultural level and for making sense of history in the learning process?

7. The Matrix for Designing the History Course

With regard to designing a concrete process of historical thinking on a concrete historical theme, trainee teachers are expected to broadly develop their planning skills as well as their observation and reflection skills in pursuit of obtaining insight into the various possibilities of work on historical narratives. This includes learning to explicate the assumptions, implications and aspects of making sense of history related to the present-day life of a concrete target group of pupils.

In the context of the initial education of history teachers at several universities and pedagogical universities in Austria, we work on improving the historical competences of trainees on both the critical work on substantive/first order concepts of historical narratives (with special emphasis on economic, social and cultural history), and the theory building with procedural/second order concepts of historical thinking and learning, as well as the organization, observation and evaluation of practical training.

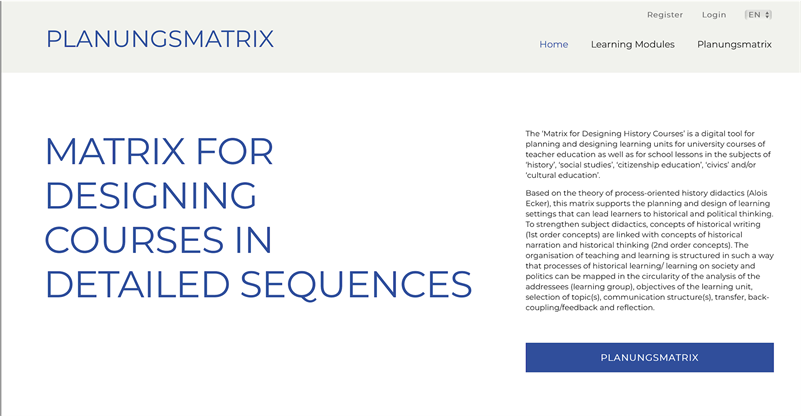

Built on the circular model of historical learning, I have developed a matrix for planning and designing the history course (Schmale et al., 2006: 118; Ecker, 2010: 178). The matrix has been completely revised over the past two years and is now available in digitalized form. It can be filled in, saved, copied, communicated to the trainer and/or to peers who are collaborating in a working group. The matrix can also be saved and archived for research purposes. An online-version of the tool is available via the platform of the “Center for Intercultural and Transnational Research in History Didactics, Social Studies and Citizenship Education” (https://geschichtsdidaktik.eu/en/projects-conferences/ongoing-projects/ last attempt July 20th, 2022). It can also be downloaded directly via the TEEM-website (https://teem.geschichtsdidaktik.eu; and https://matrix.geschichtsdidaktik.eu, last attempt July 20th, 2022)—After registration with his/her username, Email-address and password, a new user gets full access to all features of the “Planungsmatrix”. (Image 4)

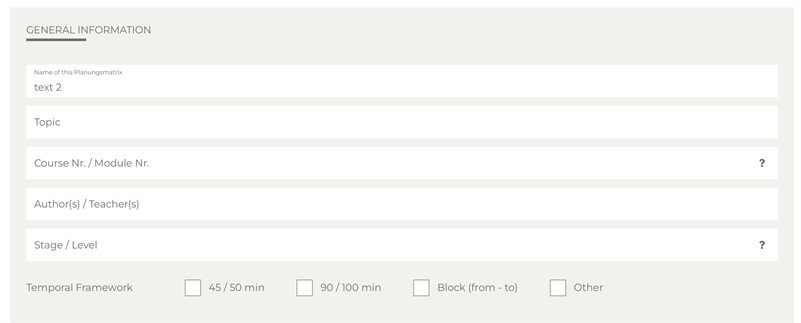

As for the exact description, the head of the matrix gives General Information about the historical topic which will be designed for historical learning, about the authors and/or the teachers of the course, and—as far as relevant—about the framework of the curriculum for the concrete target group. (Image 5)

Emphasis is then given to indicating the Substantive concepts/First-order concepts which are planned to be elaborated during this course in coherence with the topic of the course, e.g. the concept of “power”, “domain”, “democracy”,

Image 4. Head of the matrix.

Image 5. General information.

“fascism”, “feudal system”, “industrialization”, “modernity”; “distribution of resources”, “social stratification”, “conflict”, “identity”, “gender”, “culture” et al.

Equal emphasis is given to work on the Procedural concepts/ Second-order concepts which are in the focus of the specific design for the concrete history lesson. These concepts have been grouped as “second order concepts” (Lee & Shemilt, 2004) or, e.g. for the purpose of planning, as “procedural concepts” (Historical Association, 2020). The “second order concepts” comprise logics of theoretical and/or methodological approaches to historical thinking and the creation of historical narratives such as “evidence”, “historical empathy”, “perspective” (Lee & Ashby, 2001), “cause and consequence” (Lee & Shemilt, 2009), “significance”, “continuity and change” (Seixas & Morton, 2013), “similarity and difference”, “interpretations” (NC-UK, 2013), “contestability” (NC-AUS, 2017) et al. In our conception we mainly work with the Historical thinking concepts as described by Seixas (2015) (Image 6).

In the preparation for filling in the matrix we are working with the trainee students to mainly focus on one or maximal two concepts so that they will have a clear thematic focus in their lessons.

When working with the matrix, the emphasis on the conceptive approach is expected to build awareness on the interplay between first and second order concepts. We observe a growing interest in historical education for this interplay

Image 6. Substantive/first order concepts and procedural/second order concepts.

between first and second order concepts, not only as concerns the practical level but also as concerns the research and the theoretical reflection on such “close relationship with practice” (see for example Lee & Chapman, 2019: 201ff).

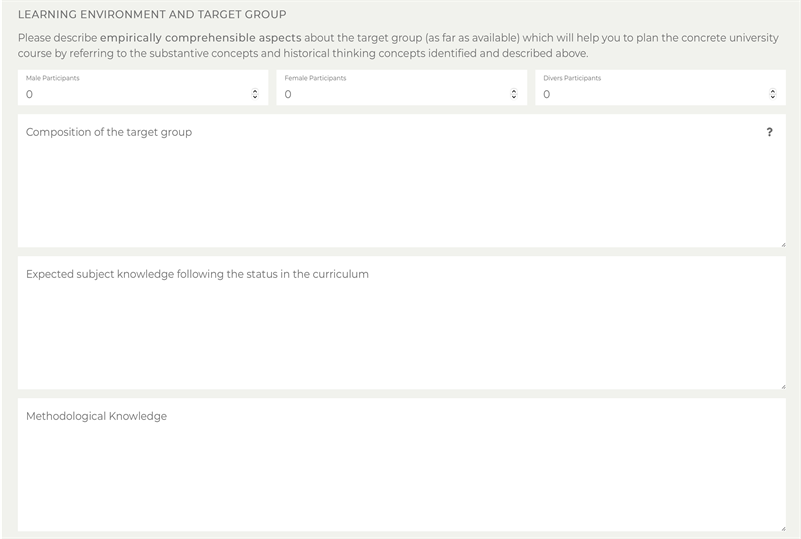

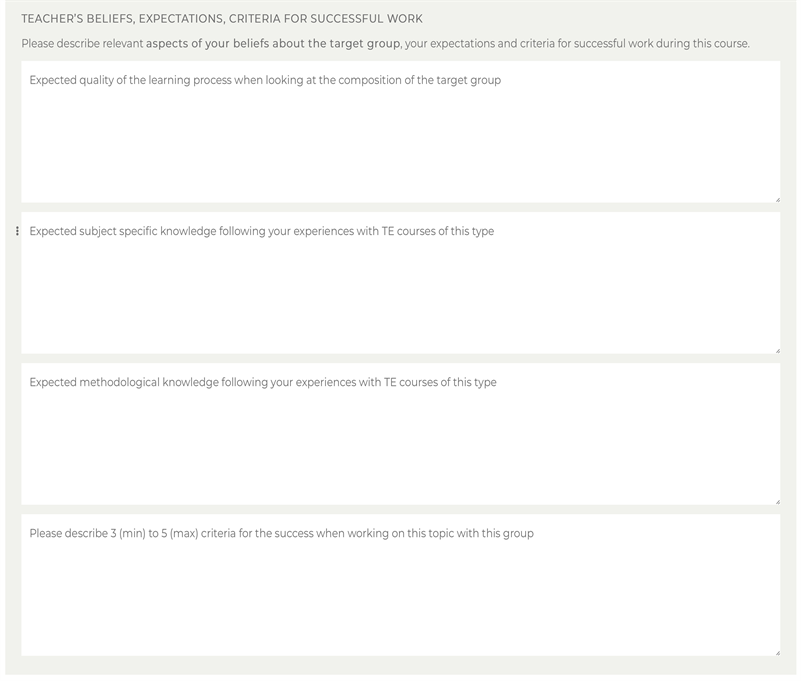

Strong emphasis is also placed on collecting information in advance about the Composition of the Target Group, e.g. the size of the group, the gender distribution, social and/or cultural background, but only as far as such information might be relevant for working on the concrete topic which is planned. Additional information goes to the expected subject/content knowledge of the target group and to its methodological capacities (Image 7).

In parallel, students/teachers are encouraged to describe their Pre-concepts and Teacher’s Beliefs about the target group which they will teach, the expectations about their knowledge, along with their methodological skills. Finally, they are invited to formulate Criteria for Successful Work which they will take as indicators for the success of the learning process which they are going to initiate and steer (Image 8).

The Principal Part of the Planungsmatrix is then dedicated to the organization and the detailed planning of the course in smaller sequences. These sequences should be filled in a row from left to right each, and are supposed to give basic information about:

1) The organizational structure of the course, such as the time space, the function

Image 7. Composition of the target group, expected knowledge and skills.

Image 8. Pre-concepts and teachers beliefs, criteria for successful work.

in the learning process (e.g. opening, introduction to the topic, elaboration of questions on the topic, presentation of results from group work …). The following columns have to indicate.

2) The detailed aims and rationales for this sequence, which give also the possibility to exemplify more in detail some interlinks to the second order concepts/procedural concepts of historical thinking.

3) Aspects of the topic to be elaborated in this sequence, including the first orderconcepts /substantive concepts to be elaborated.

4) The structure of the communication which is designed to support the learning process (hierarchic, team-oriented, process-oriented), see Ecker (2002).

5) The ways of analysis and interpretation of historical narratives and/or historical sources, as well as the forms of the transfer.

6) The forms of back-coupling/feedback with special emphasis to the self-reference of the learning group.

7) the forms of reflection and self-reflection which are planned or might be relevant for initiating the learning and working process of this course in both the personal dimension (teacher’s self-reflection) and the dimension of the learning group (Image 9).

The online version allows for reference to background information which is offered to the trainees, e.g. models of planning, hints for organizing the learning processes, examples of good practice, models for working with back-coupling, ideals for initiating reflection in a group setting. Trainee students are expected to build up their theoretical abilities and competencies in history didactics when frequently working with the matrix.

At every single workspace of the matrix, it is possible to implement direct URLs, digitalized historical sources, pictures or videos, so that the matrix can serve as a concrete “script” for the teacher when teaching in the classroom.

Image 9. The Principal Part of the Planungsmatrix.

Larger sources for the work in classroom can also be attached at the bottom of the matrix (Matrix attachments).

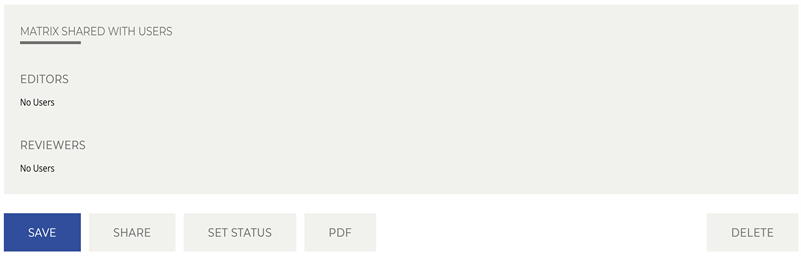

The online-version further allows giving written feedback to every single workspace of the matrix from the side of a trainer/reviewer. This function further allows e.g. for the teacher educator, to enter in detailed explication and communication with the students in phases of distance learning or blended learning. The author/students/teacher trainees can also invite colleagues to collaborate on the same matrix via the “share”-button and/or invite any supervising person for review of the completed matrix. This gives the possibility for an invited (peer) reviewer to write comments, suggestions, additional information etc. The trainer/reviewer has to be invited by the author of the matrix, so that also this function underlines the collaborative conception of the Planungsmatrix (Image 10).

In contrast to many other tools for the planning of lessons, special emphasis is placed on the communicative aspects of organizing and steering the learning process. These elements are supposed to help raise awareness for empowering self-reflection, identity-building and making sense of history by communicating about differences in historical narratives, by comparing, analysing and negotiating (variations in) historical narratives—and thus contributing to critical reflection of the construction of such narratives.

In the overview, the matrix contributes to a visualization of the learning process planned. Processes of communication, back-coupling and reflection will be highlighted with the aim of strengthening aspects of identity-building and historical sense-making.

White spots in the matrix should help the trainee to critically reflect on the planned design and thereupon eventually improve on the planning accordingly. The completed Planungsmatrix can also serve as a reference script for the empirical observervation of a concrete course (Paireder, 2021). During such observation work on e.g. the differences between the planned lesson and the transfer of the plan into praxis could be the topic of investigation.

Questions for the analysis of a completed matrix go to the overall construction

Image 10. Invited editors, invited reviews, share-functions.

of the learning process, to the interrelationship between substantive and procedural concepts, and to the structures of communication in the history course. Results of such analysis will be primordially used as feedback to the trainee students. The analysis can also generate new research questions to be investigated in empirical research on communicative processes in the history course.

Questions for the analysis can further go to identity building (reflection on differences as well as links between the narratives about the individual living environment of students and the professional historical narratives on aspects of social history, e.g. gender history15, history of childhood, of youth culture, family structures, of labour conditions, of leisure culture etc.), to tensions between individual narratives and professionally created structural narratives, or to aspects of making sense of history (structures of communication in relation to forms of transfer, of back-coupling and of reflection when working on sensitive historical topics, race, genocide, post-war narratives, migration).

8. Conclusion

The process of historical learning in the history course is regarded in this paper as a social system in its own right. The social subject in the sense of social systems theory is understood as a communicating person who analysis, invests, adopts, negotiates, reflects and decides on historical narratives in a process of co-construction with other persons. In this approach, historical consciousness is conceptualized as a form of social construction: it develops in the “here and now” of communication with others.

The idea of “historical consciousness” which is constituted in the here and now of communication with other persons is exemplified in this paper with the example of a digitalized tool for the planning and observation of historical learning, namely the Planungsmatrix. The “matrix for designing the history course” helps raise awareness on the part of the teacher trainees about conscientiously using first and second-order concepts when planning and steering the learning process. It furthermore puts emphasis on empirical observation and analysis of historical education in the classroom and therein puts the learning “social subject” in the focus of the research.

What is basically needed for e.g. empirical research in the classroom is a change of paradigm in the focus of observation. That is, the emphasis has so far been placed primarily on the “social subjects” who present narratives or listen to the presentation of narratives. What is needed in the future is research on the knowledge management of “participating social subjects” (teacher AND students) who organize both the work on historical sources and historical narratives and research on the “social subjects” who are communicating about narratives, who are analysing, de-constructing, investigating, negotiating and staging historical narratives.

The use of the matrix will contribute to establishing a culture of teacher education which places stronger emphasis on theory-driven planning and observation of the learning process. It can furthermore contribute to changing the paradigm from normative discussion about historical learning towards empirical observation and analysis of the processes of communication when “teaching and learning history”.

NOTES

1The Erasmus + Project “TEEM” provides modules for teacher education in the Civic and History Education-subjects (=the CHE-subjects: history, civic/citizenship education, social studies, cultural studies). The modules are conceptualized for working in transnational perspective. They include contextualized historical sources, case-studies, proposals für course design as well as background-information to the topic. See https://teem.geschichtsdidaktik.eu (last retrieved on July 5th 2022).

2When comparing the terminology on aspects of “historical learning” in a global perspective, a fragmentation is visible as concerns the denomination of the discipline. The term “history didactics” as promoted by the International Society of History Didactics emerges from the German speaking community. It gets growing acceptance in countries of East Europe, Asia, Africa and Latin America. There is no comparable term in the Anglophone world to describe both, the theory and the methodology of history education. For many years the disciplinary interests have been circumscribed in the Anglophone regions by the double term “history teaching and learning”. More recently, the term of “historical education” has gained broader acceptance.—For the intercultural and transnational discourse on core concepts in history didactics compare the discussions at the Center for Intercultural and Transnational Research in History Didactics, Social Studies and Citizenship Education, Retrieved July 4th, 2022 from https://geschichtsdidaktik.eu/en/.

3In “THE Leaders Survey”, a global survey organized by the Times among 200 prestigious universities worldwide in the first three weeks of May 2020 (53 countries across six continents), university leaders reported that almost all universities (189 of 200) shifted at least a quarter of their instruction to online, and more than half transferred all of it. Jump (2020) THE Leaders Survey: Will COVID-19 leave universities in intensive care? Retrieved July 06, 2020 from https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/leaders-survey-will-COVID-19-leave-universities-intensive-care.

4In the “disciplinary matrix”, Rüsen developed this concept of historical consciousness and historical thinking in relation to the daily practice of “human beings” (Rüsen, 1983: 29); see also: Lee (2004: 141).

5The idea that the man of modernity is immersed in history and/or encounters the historicity of humanity was first developed by Koselleck (1979). For deeper understanding and critical discussion, compare also Koselleck & Gadamer (1987). The understanding of the man of modernity who encounters the dynamic of industrialization and feels challenged to reflect his/her place and his/her possibilities for action (Handlungsmöglichkeiten) in this dynamic, builds the basic episteme of “historical counsciousness”, as it has been discussed by Gadamer (1960) and Ricoeur (1983, 1984, 1985)— Rüsen (1983: 50) added to the concept of “historical consciousness” the idea that “human beings” “gain identity” by thinking about time in a dual perspective: by evaluating the experience of the past und by developing ideas about their possibilities for acting in future life (intentions). By applying this form of historical thinking—driven by intentions for the future—human beings “gain time”, while when remaining in (melancholic) contemplation of the past, they “lose time” (1983: 50f).

6The model is applicable for all levels of “historical learning”, the courses in teacher education at universities and pedagogical universities, the history lessons in school, but also the courses of continuous professional development or the courses for the training of trainers (cf. Ecker, 2003: 21p). However, to remain clear in the focus of observation and reflection, the attention in this paper is given to the level of teacher education at universities, on the example of the “history course”.

7Forms of teaching which are geared towards generating knowledge which can be tested in exams have a specific social function: they are similar to initiation rites in that they help testees to gain experience in overcoming their fears. They are less amenable, however, to creating insight into the subject field or to develop social competence. On this compare also Erdheim (1984), also Bernfeld (1925) and Luhmann & Schorr (1979).

8Compare Luhmann 1984, 1995 and Luhmann & Schorr (1979), also Schön 1987, Argyris 1999.

9Ideas to this approach, but more focused on the individual learner, can be found at Schön (1987).

10 Luhmann (1995) Social Systems. Translated by J. Bednarz Jr., Standford: Stanford UP, p. 139.

11The debate in history didactics offered a series of models about the required competences for history education (Körber, Schreiber, & Schöner, 2007; Pandel, 2006; Gautschi, 2009). However, compared to these normative prescriptions for history education, there was only little debate on the theoretical basement of such competences, and there is still relatively few empirical research and publication on how to develop and achieve such competences.

12The “production of meaning” characterizes in general the learning group as a concrete (or closed) system. Albeit, the learning system combines closure and openness in the sense that “for all internal operations, meaning enables an ongoing reference to the system itself and to a more or less elaborated envirionment” (ibid.). For the system of “historical learning” we have to clarify both, the internal operations of making sense (e.g. by communications on history between the social subjects involved), and the relations of that concrete social system of historical learning to the environment (e.g. by relation to the other sub-systems at school or university, the educational policies of the region, the cultural traditions etc.).

13Certainly, it does not change the linear conception of (historical) learning, to just “turning Bloom’s taxonomy on its head”, as Sam Wineburg (2018: 81pp) proposes.

14See e.g. Ecker (2002).

15Compare the Planungsmatrix from a TEEM-workshop on 24th June 2022, guided by Alois Ecker and Bettina Paireder, on the topic “LGBTQ + Protest movements as examples of active citizenship”, Retrieved on 15th July 2022 from https://matrix.geschichtsdidaktik.eu/matrix/59.