Investigating Teacher Assessment Practices in the Teaching of Social Studies in Malawian Primary Schools ()

1. Introduction

Malawi adopted the Outcome Based Education (OBE) system in its primary school curriculum in 2001, marking a paradigm shift from an objective based to outcome based curriculum framework (MOE & MIE, 2007). The move to OBE therefore marked a significant paradigm shift in the way the schools were operating, in the overall organization of the curriculum and in the teaching and learning process. The reform came as a result of dissatisfaction with the 1991 curriculum, in addition to shifting global trends in teaching towards a learner centred approach (Kaambankadzanja, 2005; Bisika 2005, Chimombo, 2005). A critical element in this curriculum reform is the incorporation of continuous assessment (CA) which has been underscored as an integral element in the teaching and learning process.

The issue of continuous assessment in Malawi can partly be traced from the feasibility study on Improving Educational Quality Project (IEQ) funded by USAID (IEQ, 2003). The results of the longitudinal study by IEQ revealed that the majority of pupils who were unable to read, write or perform simple mathematical tasks improved after being exposed to CA. Following the success stories of the project which was presented during the conference in Blantyre, the idea of CA was carried forward to the primary curriculum conceptualisation in 2003 (Mchazime, 2003).

1.1. Study Rationale

The rationale of this study is to suggest ways improving teacher assessment practices in view of the study findings. In this way, it will contribute to the general discourse among educational practitioners on ways of improving quality delivery of education in Malawian schools following the curriculum reform. In addition, stakeholders may use the findings of this study to provide appropriate support to educations institutions.

1.2. Statement of the Problem

The introduction of CA as integral element of teaching and learning in the PCAR following the adoption of OBE was thought as a panacea to the educational challenges Malawi had been experiencing for the past years. However, the primary education institutions and teachers still operate in the strained environment characterised by, high pupil permanent classroom ratio (PqCR), high pupil-qualified teacher ratio, high repetition rates, and low completion rates (MoEST, 2019). This situation portrays a system which is inefficient thereby exacerbating the already existing burden in the education sector. Over ten years have passed after the integration of CA in the teaching and learning process, it remains unclear whether primary school teachers are using CA to improve learning.

1.3. Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to investigate teacher CA practices in the teaching of social studies in Malawian primary schools. The focus of the study was to seek deeper understanding on how CA is used to support learning in line with the 2007 Primary school Curriculum and Assessment reform (PCAR).

1.4. Research Questions

The following was the main research question which guided the study:

What are the teacher CA practices in the teaching of social studies in Malawi?

The following specific research questions guided the study.

1) What forms of CA are used by teachers when teaching social studies?

2) What is the nature of CA tasks used by teachers in social studies?

3) How frequently are the CA tasks given to learners in social studies?

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Concept of Assessment

The concept assessment and continuous assessment are not new in the education arena. MoEST and MIE (2006) look at assessment as “the process of collecting and interpreting information on learners which shows whether there has been changes in learner’s behaviour after instruction” (p. 65). Coleman et al. (2003), define assessment as all activities undertaken by teachers and learners in judging themselves, which provide information to be used as feedback in order to modify the teaching and learning activities in which they are engaged. Chilora, du Plessis, Kamingira, Mchazime, Miske, Phillips, and Zembeni, (2003), define continuous assessment as “making observations and collecting information periodically to find out what a pupil knows, understands and can do” p4. As the name suggests, continuous assessment is an ongoing process. Continuous assessment therefore plays a significant role in the teaching and learning process.

2.2. The Role of Formative Assessment in the Learning Process

Bill and Marie (2014) note that traditionally assessment was designed to grade a learner in order for them to earn a certificate at the end of the academic programme. It was noted that the traditional forms of assessment promoted recall of facts because it measured the ability of learners to replicate what was considered as truth from teachers as well as authoritative literature (DoE, 2008). This attracted widespread criticism, hence the popularisation of formative assessment which is sometime known as assessment for learning under the brand of continuous assessment (CA). It is argued here that CA promotes learning since it is designed to assist the learning process. Coleman et al. (2003), affirm that there is resounding research based evidence that CA raises standards even to learners who are considered as low achievers. They reveal five key factors that assessment makes in order to improve performance, and these are; provision of effective feedback to pupils which is regularly discussed with them; the active involvement of pupils in their own learning; adjusting teaching to take into account the results of assessment; the recognition on the influence of assessment on motivation and self-esteem of pupils both of which are crucial influences on learning and the need for the pupils to be able to assess themselves and understand how to improve their learning.

The use of CA has been incorporated in various education reforms around the world. Those advancing it point out that CA gives an opportunity for all pupils to succeed in school. They argue that by continually observing pupils to see what they know, helps the teachers to make sure that all pupils excel (Mchazime, 2003). According to IEQ (2003), CA helps the teacher to find out what the pupil knows and can do. As a result teachers can be able to provide necessary assistance. Secondly, knowledge of learner’s attainment assists the teacher to teach better. Teachers adjust their teaching to accommodate needs of the individual learners hence they become effective in the teaching and learning process. This is in tandem with the ideals of OBE that all students can learn and succeed. This being the case, CA is critical to the realisation of OBE assumption that all learners can succeed though at different rates (Killen, 2009).

2.3. Continuous Assessment Practices in Other Countries

Following the growing popularity of CA over the past years, many countries incorporated CA in their education systems. The implementation of CA in schools is therefore instrumental in aligning with the paradigm shift and education transformation in various countries. In Ghana, a study was conducted in order to understand how some Ghanaian teachers felt and thought about their respective classroom roles and their pedagogical thinking in respect to policies to improve education practice (Akyeampong, Pryor, & Ampiah, 2006). Its findings indicated that the use of CA was at variance with policy expectations.

In Zambia, Kapambwe (2010) investigated the implementation of school based CA. However, the findings revealed that effective implementation of CA was marred with several challenges. Large class sizes coupled with low staffing levels in some instances resulted into no administration of CA. In South Africa, the use of CA was incorporated in curriculum 2005. However, in a study by Vandeyar (2005) regarding assessment practices in South African primary schools undergoing desegregation revealed that teachers reacted differently to the new assessment regime. One group of teachers did not accept the policy wholesome and had to implement it the way they felt it benefited the learners. The other group of teachers entirely rejected the new approach in favour of the traditional approach. While others implemented the wrong way as a result of poor understanding of the reform. A similar study by Vandeyar and Killen (2003) found out that whether teachers use assessment formatively and summatively depended upon their conception of assessment. They also noted that the use of CA in the context of OBE was merely used for testing which was far removed from the basic principles of OBE.

2.4. Theoretical Framework

Principles of OBE were used as the theoretical framework for the study. Principles of OBE provide an insight on teacher CA practices in line with the desires of the curriculum reform towards OBE. The basic premises of obe are; clarity of focus, design down, high expectations and expanded opportunities. Clarity of focus necessitates the need for curriculum developers to define the significant outcomes that learners are required to achieve, for instance syllabus outcomes (Killen, 2009). Simply put, clarity of focus requires defining the intended learning outcomes that students are expected to achieve (Fitzpatrick, 1995 cited in Bean, 1995). In this case, both teachers and learners are aware of the learning intentions right from the beginning. Assessment is critical in this principle. Teachers must ensure that all assessment must be focused on these clearly defined important outcomes. In this case, both outcomes and assessment guide the teaching and learning process. Killen (2009), considers the process of design down as coming up with long term significant outcomes which becomes the starting point for curriculum design. One important feature of OBE is the coming up of the long term significant exit outcome.

The principle of high expectations entails that teachers must expect all learners to achieve the exit outcomes which are significant. Fitzpatrick (1995) in Bean (1995) adds that this principle emphasises the importance of defining standards for learning which must be clearly articulated to learners prior to instruction. The implication is that teachers should not give up in providing support even to those learners who are perceived as less achievers. This principle also recognises the need to provide learners with challenging tasks beyond memorisation to promote deep thinking (Killen 2009, Fitzpatrick in Bean, 1995). This is in contrast to traditional assessment procedures which merely focused on accumulation of discrete facts and skills divorced from learning (Vandeyar & Killen, 2003).

Following high expectations, there is a need to help learners reach high standards, thus the expanded opportunities principle. Spady (1994) argues that given appropriate learning opportunities most students can achieve high standards of learning. Killen (2009) points out that this principle can be achieved if students are given diverse opportunities to learn. Killen further expresses the need for flexibility in approaches to assessment. Fitzpatrick (1995) in Bean (1995) notes that this principle is at variance with the way schools were organised. In tradition setting, time was organised as a fixed constant while achievement was a variable. Vandeyar and Killen, (2003) assert that teachers are supposed to provide learners with unlimited number of opportunities to demonstrate what they have learnt. In addition, expanded opportunity relates to assessment principle of fairness. Vandeyar and Killen (2003), claim that it is not fair to expect that all learners would be ready for assessment at the same time nor expect to judge learners’ achievement on the basis of limited number of opportunities. Based on Vandeyar and Killen claims, it can be noted that for the principle of expanded opportunity to be realised, there is need for a highly differentiated instruction and assessment activities.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

Methodology is viewed as “the rationale and the philosophical assumptions underlying a particular study” (Wisker, 2008: p. 67). The study engaged in a qualitative methodology using case study approach. Literature on case study provides diverse views regarding what a case study is. However, Yin (2002) is among the seminal authors regarding literature on case study. Yin (2002) in his definition considered a case study as an empirical study that investigates a contemporary occurrence within its actual context which involves the use of multiple sources of evidence. Yin (2002) further defines a case as “a contemporary phenomenon within its real life context, especially when the boundaries between a phenomenon and context are not clear and the researcher has little control over the phenomenon and context” (p. 13). The case study methodology was appropriate for this research because it helped in providing a deeper understanding of the classroom dynamics in as far as continuous assessment is concerned. Kothari (2004), highlights that a case study focuses on a comprehensive study of “a person on what he does, what he thinks he does and has done and what he expects to do and says he ought to do” (p. 113). Similarly, this study focused on teacher practices in the use of CA which constitute what they think and say about CA and the actual practices in the teaching and learning process. It is for this reason that the case study approach used, is an important tool in studying the recent innovation on CA in the PCAR.

3.2. Study Site

Three primary schools from Rumphi district were purposively selected in this study. For the purpose of anonymity and confidentiality each school was given a pseudonym. Alphabetical letters B, L, and S were used in place of the real names. In this study, eight primary school teachers were sampled. Each school and participating teachers were given pseudonym in order to ensure anonymity. Names of the schools were referred to as school B, L and S. Each teacher per school was labelled T1, T2 and T3. When describing the participating teachers, the first letter represented the name of the school followed by the labelling for a specific teacher. Based on that the sample had the following participating teachers, BT1, BT2, BT3, LT1, LT2, ST1, ST2, and ST3, making a total of eight teachers.

3.3. Data Generation

This study used three methods of data generation and these were; face to face interview, classroom observation, and document analysis. Triangulation of all these data generation methods provided a rich perspective from different angles on the use of continuous assessment in the implementation process. There was one long face to face semi structured interview with each participating teacher which took an average of fifty minutes followed by a series of short five to ten-minute follow-up interviews conducted during the study. A total of eight long interviews were conducted on all the participating teachers. I used open ended semi structured interview and listened carefully about what teachers said on their continuous assessment practices. These interviews enabled me to get thick descriptions of participant’s continuous assessment practices. The long semi structured interview for each participating teacher was aimed at finding a number of key issues relating to the study. These key issues were: preliminary data about the participants in terms of their background information which included education qualification, experience, and teaching load. In addition, the general CA practices in terms of planning, feedback, CA data management, and CA tasks.

Apart from the semi structured interview, lesson observation was another way of generating data for the study. This was so because the study’s interest hinged on teacher CA practices. Walliman (2011), notes that observation just like other strategies help to record data about events and activities. What is observed is the event or phenomenon in action (Tuckman, 1994). Lesson observation therefore offered an opportunity for data triangulation. A total of forty lesson observations were done. Each lesson observed took thirty minutes. Five lesson observations were done on each of the eight participants upon reaching the theoretical saturation (Auerbach & Silverman, 2003).

Finally, this study used document analysis. Document analysis was an important method which provided artefacts on teacher practices. Documents are thus important in that they assist in verifying or supporting data obtained from interview or observation and vice versa (MacMillan, 2004). Yin (2002) recognizes a critical role of documents in any case study. He argues that documents help to corroborate with evidence from other sources. Teachers are required to come up with documentation such as, learner progress books, lesson plans, schemes and records of work and assessment tasks. In addition, students work provides valuable information about classwork. These are important documents which highlight important episodes regarding the teaching and learning process.

4. Findings

The study findings focused on three major aspects and these are; the forms of CA tasks use by social studies teachers, the nature of the CA tasks and the frequency and function of CA tasks.

4.1. Forms of Tasks

The findings show that two main types of CA were used by the participating teachers, namely, paper and pencil tests and question and answer. However, student presentations of their own work were also used at times.

4.2. Paper and Pencil Tests

The new curriculum and assessment framework demand teachers to use CA in form of formative assessment in order to support learning (assessment for learning). During face to face interviews regarding the forms of CA tasks the teachers were using, the study found out that paper and pencil tests constituted the main tasks given to learners. The following teachers had this to say:

… so they cover the first topic then the other… then the other and they go up to the fourth so you ask them like may be the latitude you can ask them what are latitudes? Or what are longitudes? Mention the importance of latitudes or longitudes these are some of the questions. (Teacher ST1, face to face interview 20.04.2018) We just put multiple choice questions. We also add some questions which demand reasoning such as questions which demand one to explain. We put some questions without putting answers so that we should see whether the learner can think. But on multiple choice we put answers. But in other questions learners have to write their own responses. (Teacher BT1 face to face interview, 20.06.2018) I usually take the Malawi National Examination Board (MANEB) type I use the past papers. When asking questions I use the past papers. Just for them not to be so that they should be familiar with those tests to those assessments. (Teacher BT2face to face interview)

In the above quote, teacher ST1 mentioned that formal paper and pencil tests were used in assessing learners after completing a given topic and teacher BT1 highlighting some of the types of the questions administered during the paper and pencil tests. This was collaborated by teacher BT2 who said that she used MANEB past papers when administering formal tests.

4.3. Question and Answer

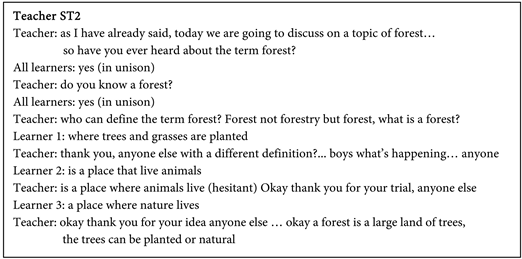

Apart from paper and pencil tests, question and answer featured highly as a form of CA task used by participating teachers. Question and answer methods is also known as Socratic or heuristic method. In this method, a series of carefully designed questions are used to elicit a solution to a problem. Data from classroom observations showed that all the lessons observed from participating teachers used question and answer as a form of assessing student learning during lessons. A series of lesson observations were made to have an overview on teacher use of CA in the teaching and learning process. Box 1 represents teacher CA practice on question and answer as a form of CA.

Box 1. An extract of a lesson plan focusing on question and answer.

The form of continuous assessment in the lesson observation above is question and answer. This was confirmed during the post observation interview where the teacher claimed that, the questions asked were aimed at finding out learner understanding and progress. This was collaborated by teacher ST1, ST2 and LT2 and other five participating teachers who indicated the use of question and answer as a way of assessing the progress of the lesson. The only variation among them was the degree to which they used various CA tasks.

4.4. Student/Group Presentation

The study findings reveal that the participating teachers used group presentation as a way of assessing learners. During face to face interview, teacher BT2 indicated the use of group work presentation as a way of checking learner’s progress, “I use group presentation in order to assess them”. Teacher BT2 highlighted that the overall group presentations enabled her to have an overview of how the lesson was faring, in that if many groups failed to present the right answers she considered revising the lesson or coming up with a remedial lesson. Teacher ST2 expressed similar practices as expressed by teacher BT2 by saying,

say, yaah aah actually just because they are … we are using group we give them the topics where to read … first we are going to ask you this, for examples weekly the work which has been covered that week its where we ask questions. Then we tell them that they should also read that part or else we just discuss the topic and they should ask each questions. Later they are given assessment at the end of each week (ST2 face to face interview 19.04.2018, 8am)

Another lesson observation summary showed that teacher ST1 incorporated group presentations as depicted in Box 2.

Box 2. An extract of a lesson observations summary for teacher ST1.

In Box 2, teacher ST1 after post lesson interview indicated that group work and presentation served two purposes, one as a learning activity and two as a way of assessing them.

4.5. Nature of Assessment Tasks

Apart from the forms of continuous assessment tasks, the study explored the nature of continuous assessment tasks. The focus was to explore how teachers framed continuous assessment tasks to promote learning in line with the demands of CA in the PCAR.

In this study, oral question and answer and formal questioning through periodical tests formed an important part of teacher CA practices. The findings of the study revealed that questioning was a major strategy which was used by the participating teachers as an assessment tool that informed their teaching and learning process. During lesson observations, it was noted that teachers mostly used oral questions in what is popularly known as question and answer method as a teaching and assessment strategy.

The study revealed three aspects during the lessons on how teachers used the questions. First, teachers asked recall based questions which required short answers and one correct response. Secondly, when teachers asked questions, learners were given the learners’ books to look for responses without engaging them in a meaningful deliberation. Thirdly, more often than not, teachers accepted chorus responses or asked consensus seeking questions that promoted whole class response. Lesson observation for teacher LT2 in Box 3 highlights questioning technique used.

Box 3. An extract of a lesson observations summary for teacher LT2.

In the above lesson by teacher LT2, on the topic HIV/AIDS, the teacher engaged learners in group work. When learners were presenting their findings, they were simply reading points from the textbooks given to them as if it was a comprehension exercise.

Apart from lesson observations, document analysis on the formal continuous assessment tasks revealed typical recall based questioning. This is illustrated from the learners marked script in Figure 1.

Figure 1, shows that all the questions are basically low order questions. All the questions are in closed format, such questions demand simple responses and generally encourage memorization.

4.6. Frequency and Function of CA Tasks

Apart from forms of continuous assessment tasks, nature of continuous assessment tasks, the study went further into finding out the frequency of assessing learners and the function of continuous assessment. The findings of the study revealed that, the frequency of administering CA varied from one individual to another, in some instances from one school to another. When asked on how they carried out continuous assessment tasks, most teachers focused on formal continuous assessment tasks given to learners fortnightly or once a month depending on the school’s culture and the teachers themselves. Teacher LT2 had this to say “… aah ... in class as such we do use it but it is difficult in the process of teaching, of course we use that but mostly what we use is that we do just assess as a class may be at the end of the month we do …” Of all the participants, only teacher BT3 indicated that continuous assessment was done in every class, the teacher had this to say;

As I have already said that we have a daily assessment we use a checklist and we have a weekly, every week you have to assess every topic that has been covered, for example that topic we are teaching today … But if they are able you can go to the other topics. So assessment happens in each and every week each and every day and in every lesson for it to be effective. (Teacher BT3, face to face interview)

![]()

Figure 1. An extract showing a marked script showing dominant lower order questioning by teacher ST1.

Even though teacher BT3 highlighted that continuous assessment was done in every lesson with the intention of helping learners, the teacher was quick to concede that the checklist which is used to do that was not used frequently due to time constraints.

With regard to functions of assessment almost all participating teachers indicated that CA results are used for promotion of learning. The following had this to say

The results from the CA available can provide us with information whether to promote the learner to another class (BT2, Face to Face interview, 21.06.2018) … that each and every month we are supposed to assess them yaah so it comes sometimes may you find that a learner at the end of the term he or she don’t write exams because of sickness or some problems so we go back to the CA ... So that assist us to make to promote that learner from one level to another so yah so is good (teacher ST1, face to face interview, 20.04.2018) … so that they should perform well at the end and also it helps in terms of ahh when a learners is sick during final exams we just use the past performance of that learner. (Teacher ST2 face to face interview, 19.04.2018, 8am) … but now you find out that by the end of the term you are going to promote learners from this class to this class. May be that term by the end of the term you will find that learners have not attended may be because he is sick or may have gone somewhere else, so through CA we just get the information because he was just writing monthly so that I can say CA we are able to promote learners based on that CA (Teacher LT1, face to face interview)

However, teachers BT3 and ST3 indicated that they used CA to improve their teaching and provide necessary support to learners.

5. Discussion

The findings of the study indicate that the formal CA and informal CA procedure in form of paper and pencil and question and answer were the dominant CA practices by participating teachers respectively. This might have been attributed to ease of use or familiarity on the part of participating teachers. Based on the findings, it is evident that teachers use paper and pencil CA tasks as a form of summative assessment as opposed to assessment for learning as espoused in the PCAR. Teacher ST1 indicated that learners were asked a set of questions after completing a topic of study. Similarly, teacher BT1 indicated that multiple choice questions and short answer questions were used to assess learners. The use of MANEB past papers by teacher BT2, further reveals how teachers were inclined to summative assessment protocols.

Another dominant finding was the use of question and answer and group presentations. This was a dominant feature particularly in lesson presentations. Burden and Bryd (2003) indicate that questioning is the cornerstone of all effective teaching. They argue that questioning plays an important role in checking students understanding, evaluating effective teaching and increasing higher order thinking. However, the findings of the study indicate that the use of questions did not support in anyway effective teaching. Teacher ST2 in Box 1 did not make any attempt to prompt learners who did not provide a satisfying answer. To the contrary the teacher went on asking other learners or just saying “thank you for your trial”. Jacobsen, Eggen and Kaucha (2002) hint that students get frustrated if teachers show no effort to assist on their responses.

In addition, during group work and presentations, the way the tasks were conducted did not demonstrate the need to evaluate students understanding or increase their higher level thinking since learners were just advised to look at the existing answers in the books. These continuous assessment practices were limited in capturing learners’ progress within the diverse learning environment. A variety of continuous assessment tasks is capable of enabling the teacher to take advantage of different learning styles of learners. Hansen (1989), hints that OBE encourages teachers to use different ways of continuously assessing students such that there is a move from predominantly multiple choice tests to demonstration, observation, task completion, self-assessment, and student projects.

Limited number of continuous assessment tasks participating teachers in the study gave to learners provided limited lens through which to effectively assess learners for meaningful learning. Brookhart & Nitko (2008) argue that giving learners multiple assessment tasks gives them many opportunities to show what they know. Chan (2007) further argues that learning progress cannot be measured by a single assessment task.

As a result of this, participating teachers did not provide expanded opportunities as required by principles of OBE. In addition, the tasks given to learners did not stretch their minds as such teachers seem to have low expectations as opposed to high expectations as propagated by OBE principles (Killen, 2009).

The finding in Figure 1 reveals that the questions reflect the lower order as per Blooms Taxonomy. This is contrary to the demands of the PCAR. Gromlund (2006) in his studies on assessment reveals that such type of assessment practices reflects traditional assessment practice grounded on low level questions with low impact on students’ academic. It would have been important if teachers asked learners to explain their responses either in oral assessment or written work. It is only when learners are engaged in explaining their position that teachers would be able to know that learners understand the material or not.

With regard to frequency of assessment tasks, the findings of the study reveal that participating teachers conducted CA fortnightly of monthly. This is a revelation that their interest was to check learner’s progress after completing a series of topics. This CA practices best describes the summative approach to assessment as opposed to formative approach to assessment as propagated in the PCAR. The idea of summative approach to assessment is further supported by the responses which teachers made with regard to the functions of CA of which most participants indicated that they use the results for promotion purposes. However, teacher BT3 and ST3 indicated that CA assists them to come up with remedial lesson to support the learners. This is exactly what OBE principles call on teachers to do in order to ensure that all learners reap the benefit of teaching and learning (Killen, 2009).

6. Conclusion and Recommendation

6.1. Conclusion

In view of the findings, it can be concluded that the integration of assessment into the teaching and learning as practiced by teachers in the study area exposes gaps in the implementation of CA. Teachers’ CA practices in the selected primary school weakly supported the demands of the PCAR. Secondly, the majority of teachers concentrated on administering formal assessment tasks in form of tests at the expense of other formal and informal tasks that could generate vital data to support everyday learning. The findings demonstrate that it is not enough simply to change emphasis of assessment from summative to formative in form of CA, but helps practitioners understand the essence of CA. Despite the gulf existing between the expectations of CA and practice, it is noted that CA remains a viable approach to improve performance if practitioners are provided with the necessary support.

6.2. Recommendation

In view of the findings, it is noted that teachers’ assessment practices further widen the realisation of the curriculum reform goals. The assessment practices of participating teachers do not in any way promote quality learning. There is need therefore that curriculum developers put in measures that would narrow the gap between expectations and practice. I therefore argue that CA is an important professional skill that teachers must attain in order to effectively make use of CA in line with the demands of the curriculum. Critical issues to consider are planning for CA, skill in observing and generating data on learning, analytical and interpretation skill of CA data, provision of feedback and provision of learning support. This cannot merely be attained as a result of telling teachers what to do, supervision or inspection, but it calls for radical re-education to bring about transformation in teacher practices within a supportive teaching and learning environment. Malawi Institute of Education (MIE) and Ministry of Education (MOE) therefore need to address the prevailing contextual factors like class sizes, teaching staff, for the learners to reap the benefit of CA.