1. Introduction

Clifford algebras provide a unifying structure for Euclidean, Minkowski, and multivector spaces of all dimensions. Vectors and differential operators expressed in terms of Clifford algebras provide a natural language for physics which has some advantages over the standard techniques [1] - [6] . Applications of Clifford algebras and related spaces to mathematical physics are numerous. A valuable collection is given by Chishom and Common [4] . There are other applications in the literature. For example, DeFaria et al. [7] applied Clifford algebras to set up a formalism for magnetic monopoles. Salingaros [8] extended the Cauchy-Rie- mann equations of holomorphy to fields in higher-dimensional spaces in the framework of Clifford algebras and studied the Maxwell equations in vacuum and the Lorentz gauge conditions. He showed that the Maxwell equations in vacuum are equivalent to the equation of holomorphy in Minkowski space-time. Imaeda [9] showed that Maxwell equation in vacuum are equivalent to the condition of holomorphy for functions of a real biquaternion variable.

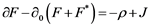

It has been shown that when the electromagnetic field is defined as the sum of an electric field vector and a magnetic field bivector, the four Maxwell equations reduce into a single equivalent equation in the domain of Pauli and Dirac algebras [3] [4] . In this work, we apply a different Clifford algebra to the Maxwell equ- ations of electromagnetism, and we show how this formulation relates to the classical theory in a straightforward manner resulting in two main formulas; the first is a simplistic rendering of Maxwell’s equations in a short formula

(1)

(1)

The second is the reconstruction of the combined electric and magnetic fields by a single transformation of the four-potential

(2)

(2)

Our investigation differs in approach from those in Hestenes and Chisholm- Common in its simplicity and ability to use a single potential function to cor- rectly derive Maxwell’s equations in a vacuum.

In what follows, we first lay out the theory of the Clifford algebra employed in this work. We then discuss its applications to electromagnetism and obtain a new electromagnetic field multivector, which is closely related to the scalar and vector potentials of the classical electromagnetics. We show that the gauge transformations of the new multivector and its potential function and the La- grangian density of the electromagnetic field are all in agreement with the transformation rules of the rank-2 antisymmetric electromagnetic field tensor. Finally, we give the matrix representation of the electromagnetic field multive- ctor and its Lorentz transformation.

2. Theory

Consider the Clifford algebra  over the field of real numbers

over the field of real numbers  generated by the elements

generated by the elements  with relations

with relations

(3)

(3)

and no others [1] [10] . As a vecor space over , the algebra

, the algebra  has dimension

has dimension . A basis for

. A basis for  consists of all products of the form

consists of all products of the form , with

, with  and

and . The empty product is identified with the scalar 1. There are

. The empty product is identified with the scalar 1. There are  such products, and an arbitrary element

such products, and an arbitrary element  of

of  (called a multivector) is a linear combination of these products. If we write

(called a multivector) is a linear combination of these products. If we write  for a multiindex

for a multiindex ![]() and

and![]() , then

, then![]() , where

, where ![]() for all

for all![]() . For instance, an arbitrary element of

. For instance, an arbitrary element of ![]() can be written as

can be written as

![]() (4)

(4)

An important subspace of ![]() is

is

![]()

which is isomorphic to the generalized Minkowski space![]() . Notice that this is a subspace of dimension

. Notice that this is a subspace of dimension ![]() rather than dimension

rather than dimension ![]() or

or![]() .

.

A product ![]() where

where![]() , or any expression equivalent to a scalar multiple of it is called an m-blade. Let

, or any expression equivalent to a scalar multiple of it is called an m-blade. Let ![]() be the sum of the m- blades of

be the sum of the m- blades of![]() , called the m-vector part of

, called the m-vector part of![]() , then

, then

![]() (5)

(5)

If ![]() for some positive integer m, then

for some positive integer m, then ![]() is said to be homogeneous of grade m.

is said to be homogeneous of grade m.

The inner and outer products of blades are defined as follows [1] : The inner product of an r-blade ![]() and as s-blade

and as s-blade ![]() is

is

![]() (6)

(6)

The outer product of ![]() and

and ![]() is

is

![]() (7)

(7)

By linearity, these definitions extend to ![]() and

and![]() , where

, where ![]() and

and ![]() are multivectors.

are multivectors.

Some examples of inner and outer products are:

![]() (8)

(8)

There are three important involutions on ![]() [10] :

[10] :

1) inversion: ![]() defined by

defined by ![]() for

for ![]()

2) reversion: ![]() defined by

defined by ![]()

3) conjugation: ![]() defined by

defined by ![]()

Then it follows that![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() for all x and

for all x and ![]() in

in![]() .

.

3. Derivatives

Let ![]() be the differential operator

be the differential operator![]() , where

, where![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be the differential operator

be the differential operator![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be a domain in

be a domain in![]() , and sup- pose that

, and sup- pose that ![]() has continuous derivatives of whatever order the context requires. Then

has continuous derivatives of whatever order the context requires. Then ![]() and

and ![]() are the left and right derivatives of

are the left and right derivatives of![]() , respec- tively. In terms of components, these derivatives are defined by

, respec- tively. In terms of components, these derivatives are defined by

![]() (9)

(9)

It is straightforward to show that the following identities hold:

![]() (10)

(10)

![]() (11)

(11)

![]() (12)

(12)

![]() (13)

(13)

![]() (14)

(14)

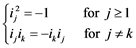

The Clifford algebra ![]() maybe written as the algebra

maybe written as the algebra ![]() where

where![]() . If we identify

. If we identify ![]() with the subspace spanned by

with the subspace spanned by![]() , then

, then ![]() is the usual skew-field of quater- nions with

is the usual skew-field of quater- nions with

![]() (15)

(15)

The geometric product on ![]() satisfies the relation

satisfies the relation![]() , where

, where ![]() is the usual cross-product. However, since additional relations exist among

is the usual cross-product. However, since additional relations exist among![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and![]() , inner and outer products are not defined here.

, inner and outer products are not defined here.

If ![]() is a vector field on

is a vector field on![]() , then it is straightforward to show that

, then it is straightforward to show that

![]() (16)

(16)

Theorem 1. Suppose ![]() is a vector field on

is a vector field on![]() . Then

. Then ![]() if and only if

if and only if![]() , where

, where ![]() is a real-valued harmonic function of

is a real-valued harmonic function of![]() .

.

Proof. A vector field ![]() equals

equals ![]() for a real-valued function

for a real-valued function ![]() if and only if

if and only if![]() . The function

. The function ![]() is harmonic if and only if

is harmonic if and only if![]() . □

. □

4. Applications to Electromagnetism

In Gaussian units, the differential form of the Maxwell equations for sources in vacuum are [11]

![]() (17)

(17)

![]() (18)

(18)

![]() (19)

(19)

![]() (20)

(20)

where![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are time-dependent vector fields in

are time-dependent vector fields in ![]() and

and ![]() is a real-valued function. That is, each quantity is a function of

is a real-valued function. That is, each quantity is a function of![]() , where

, where ![]() and

and ![]() is time. Note that

is time. Note that ![]() is the charge density multiplied by

is the charge density multiplied by ![]() and

and ![]() is the current density multiplied by

is the current density multiplied by![]() .

.

We recast the Maxwell equations in the language of Clifford algebras by keeping the electric field as a vector, but replacing the magnetic field vector by the magnetic field bivector![]() , defined as [3] [12]

, defined as [3] [12]

![]() (21)

(21)

The electromagnetic field multivector is then defined as![]() . It can be shown that

. It can be shown that

![]() (22)

(22)

![]() (23)

(23)

![]() (24)

(24)

![]() (25)

(25)

![]() (26)

(26)

![]() (27)

(27)

In terms of ![]() and

and![]() , the Maxwell equations for sources in vacuum may now be written as

, the Maxwell equations for sources in vacuum may now be written as

![]() (28)

(28)

![]() (29)

(29)

![]() (30)

(30)

![]() (31)

(31)

Theorem 2. The Maxwell equations are equivalent to the single equation

![]() (32)

(32)

Proof. Since![]() ,

,

![]() (33)

(33)

Using the Maxwell equations, we obtain

![]() (34)

(34)

But

![]() (35)

(35)

Therefore, we obtain Equation (32). Conversely, assuming Equation (32), the Maxwell equations follow by setting the real parts, the vector parts, the bivector parts, and the trivector parts of each side equal. This completes the proof. □

From classical electrodynamics [11] , the fields ![]() and

and ![]() are derived from a scalar potential

are derived from a scalar potential ![]() and a vector potential

and a vector potential ![]() by

by

![]() (36)

(36)

![]() (37)

(37)

where ![]() and

and ![]() satisfy the wave equations

satisfy the wave equations

![]() (38)

(38)

![]() (39)

(39)

and the continuity equation

![]() (40)

(40)

We can formulate this as follows: Let![]() , and write

, and write

![]() (41)

(41)

where ![]() and

and![]() . Then

. Then

![]() (42)

(42)

![]() (43)

(43)

Note that![]() .

.

The derivative of ![]() is

is

![]() (44)

(44)

Using Equations (42) and (43) and noting that

![]() (45)

(45)

we obtain

![]() (46)

(46)

Theorem 3. The electromagnetic field ![]() is obtained from the potential function

is obtained from the potential function ![]() by

by

![]() (47)

(47)

Proof. From Equation (46) we have![]() . Therefore,

. Therefore,

![]() (48)

(48)

□

Note that Equation (47) may also be written as![]() , since by the continuity eqation

, since by the continuity eqation![]() .

.

5. Gauges

5.1. Lorentz Transformation of the Electromagnetic Field

A Lorentz transformation is an isometry ![]() of the Minkowski space

of the Minkowski space![]() , such that

, such that ![]() whenever

whenever![]() . In the special case where one inertial reference frame

. In the special case where one inertial reference frame ![]() is moving relative to another frame

is moving relative to another frame ![]() with constant velocity

with constant velocity ![]() in the

in the ![]() -direction, the Lorentz trans- formation relating them is represented by the matrix

-direction, the Lorentz trans- formation relating them is represented by the matrix

![]() (49)

(49)

where

![]() (50)

(50)

In the general case, writing![]() , we have

, we have

![]() (51)

(51)

and

![]() (52)

(52)

Thus the operator ![]() transforms as

transforms as![]() , where

, where ![]() acts on

acts on ![]() on the right in the usual way. Calculations show that associativity does not hold in the expression. To summarize, if

on the right in the usual way. Calculations show that associativity does not hold in the expression. To summarize, if![]() , then

, then![]() .

.

Suppose now that![]() , where

, where ![]() is a potential function for

is a potential function for ![]() so that

so that![]() . Then

. Then ![]() is a potential function for the transformed electromagnetic field multivector

is a potential function for the transformed electromagnetic field multivector![]() . Therefore,

. Therefore,

![]() (53)

(53)

and![]() .

.

Theorem 4. Under the Lorentz transformation![]() , the electromagnetic field multivector

, the electromagnetic field multivector ![]() transforms into

transforms into ![]() according to

according to

![]() (54)

(54)

Again, associativity does not hold in this equation.

5.2. Lorenz Gauge Invariance

Before we get to the mathematics of this section, let us note the difference in Lorentz and Lorenz. These names, in fact, do belong to different scientists and thus we consider both types of gauge invariance here.

The common gauge invariant from classical electrodynamics is to consider

![]() (55)

(55)

![]() (56)

(56)

In our formalism this leads us to

![]() (57)

(57)

Examining this a little more fully, we know that the electric and magnetic fields do not change under Lorenz or Coulomb gauges and thus we obtain

![]() (58)

(58)

Following through we see

![]() (59)

(59)

As the multivector field must remain unchanged we obtain the gauge invariant condition

![]() (60)

(60)

6. The Lagrangian Density

Recall that in classical electromagnetism the Lagrangian density in a vacuum is given by

![]() (61)

(61)

By expanding this a bit, we find

![]() (62)

(62)

In order to recreate this in the Clifford algebraic formulation we consider

![]() (63)

(63)

Thus we might expect that the Lagrangian density becomes

![]() (64)

(64)

Examining this a little we see that

![]() (65)

(65)

Since our inner product is commutative we have a cancellation of field product terms ![]() and

and![]() .

.

In higher dimensions, one may wish to restrict to the 0-blade so as to disallow higher dimensional cross terms. Thus we write

![]() (66)

(66)

Now let’s consider the situation outside a vacuum. We have

![]() (67)

(67)

Let us write

![]() (68)

(68)

Then using our potential ![]() we have the Lagrangian density of the electro- magnetic fields outside a vacuum,

we have the Lagrangian density of the electro- magnetic fields outside a vacuum,

![]() (69)

(69)

7. Representation by Matrices

Complex numbers can be represented by ![]() matrices. Similarly, as we show in the Appendix, the Clifford algebra

matrices. Similarly, as we show in the Appendix, the Clifford algebra ![]() is represented by

is represented by ![]() matrices. The element

matrices. The element ![]() is represented by the matrix

is represented by the matrix

![]() (70)

(70)

From this we can write an ![]() natrix representation of the electromagnetic field multivector

natrix representation of the electromagnetic field multivector

![]() (71)

(71)

The ![]() matrix in the upper left corner contains all the coordinates of

matrix in the upper left corner contains all the coordinates of ![]() and is the same as the matrix representation of the second-rank antisymmetric electromagnetic field tensor [11] . If we use this representation for

and is the same as the matrix representation of the second-rank antisymmetric electromagnetic field tensor [11] . If we use this representation for![]() , that is,

, that is,

![]() (72)

(72)

then the Lorentz transformation of ![]() is given by [11]

is given by [11]

![]() (73)

(73)

A quite lengthy calculation (see Appendix) shows that the two transformations given by Equations (54) and (73) are exactly identical.

8. Concluding Remarks

We have shown that in the framework of the Clifford algebra defined in Equation (3), the Maxwell equations in vacuum reduce to a single equation in a fashion similar to that in other types of Clifford algebras. The multivector ![]() is closely related to the second-rank antisymmetric electromagnetic field tensor [11] , whose condition of holomorphy is also equivalent to the Maxwell equations in vacuum [8] . However, the multivector formalism may have some theoretical advantages over the tensor formalism.

is closely related to the second-rank antisymmetric electromagnetic field tensor [11] , whose condition of holomorphy is also equivalent to the Maxwell equations in vacuum [8] . However, the multivector formalism may have some theoretical advantages over the tensor formalism.

Furthermore, we have shown that the electromagnetic field multivector can be derived from a potential function![]() , which is closely related to the scalar and the vector potentials of classical electromagnetics.

, which is closely related to the scalar and the vector potentials of classical electromagnetics.

Finally, we have discussed the Lorentz transformation of the potential function ![]() and the multivector field

and the multivector field![]() , and have shown that these transformations are in agreement with the transformation of the second-rank antisymmetric electro- magnetic field tensor.

, and have shown that these transformations are in agreement with the transformation of the second-rank antisymmetric electro- magnetic field tensor.

The formulation given by other investigators [3] [4] differs from the present work in that they have employed the Pauli algebra in which the square of each of the three unit elements is +1 rather than −1, or the Dirac algebra in which one unit element has square +1 and three unit elements have square −1. All these types of Clifford algebras have been extensively used.

By repeating our calculations with ![]() instead of −1 in Equation (3), it can be shown that the Maxwell equations in vacuum reduce to

instead of −1 in Equation (3), it can be shown that the Maxwell equations in vacuum reduce to![]() , which is in agreement with the result given by Jancewicz [12] . Equation (47) then becomes

, which is in agreement with the result given by Jancewicz [12] . Equation (47) then becomes![]() , where

, where ![]() is the potential function given by Equation (41). Equation (54) for the Lorentz transformation of

is the potential function given by Equation (41). Equation (54) for the Lorentz transformation of ![]() then reduces to

then reduces to![]() . Repeating the calculations of the Appendix, it turns out that this transformation is equivalent to

. Repeating the calculations of the Appendix, it turns out that this transformation is equivalent to![]() , where the matrix represen- tation of

, where the matrix represen- tation of ![]() is now given by

is now given by

![]() (74)

(74)

Note that this matrix is not antisymmetric and the representation is not the same as that of the electromagnetic field tensor, and the transformation rule is also different. This is in contrast to the result obtained from applying a Clifford algebra with![]() .

.

Appendix

Here we show that the two transformations given in Equations (54) and (73) are identical.

We have

![]() (A-1)

(A-1)

and

![]() (A-2)

(A-2)

Therefore,

![]() (A-3)

(A-3)

It follows that the matrix representation of ![]() is

is

![]() (A-4)

(A-4)

We also have

![]() (A-5)

(A-5)

So the matrix representation of ![]() is

is

![]() (A-6)

(A-6)

The general Lorentz transformation and its inverse are given by the following matrices:

![]() (A-7)

(A-7)

![]() (A-8)

(A-8)

From Equation (54) we have

![]() (A-9)

(A-9)

where

![]() (A-10)

(A-10)

and

![]() (A-11)

(A-11)

Let ![]() be the m-th row of

be the m-th row of![]() . Then

. Then

![]() (A-12)

(A-12)

![]() (A-13)

(A-13)

and

![]() (A-14)

(A-14)

Recall that from Equation (42) we have

![]() (A-15)

(A-15)

and from Equation (37) we have

![]() (A-16)

(A-16)

Therefore,

![]() (A-17)

(A-17)

Then we find the following identity by carrying out the multiplication,

![]() (A-18)

(A-18)

For example, with ![]() and

and ![]() we obtain the Lorentz transform of

we obtain the Lorentz transform of![]() ,

,

![]() (A-19)

(A-19)

and with ![]() and

and ![]() we obtain

we obtain

![]() (A-20)

(A-20)

It is now straightforward to show that the identity in Equation (18) is identical to

![]() (A-21)

(A-21)

where ![]() is the transpose of the general Lorentz transformation matrix, and

is the transpose of the general Lorentz transformation matrix, and ![]() is the electromagnetic field tensor given by Equation (72).

is the electromagnetic field tensor given by Equation (72).

![]()

Submit or recommend next manuscript to SCIRP and we will provide best service for you:

Accepting pre-submission inquiries through Email, Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, etc.

A wide selection of journals (inclusive of 9 subjects, more than 200 journals)

Providing 24-hour high-quality service

User-friendly online submission system

Fair and swift peer-review system

Efficient typesetting and proofreading procedure

Display of the result of downloads and visits, as well as the number of cited articles

Maximum dissemination of your research work

Submit your manuscript at: http://papersubmission.scirp.org/

Or contact jamp@scirp.org