Some Explicit Results for the Distribution Problem of Stochastic Linear Programming ()

1. Introduction

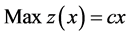

Consider the linear programming problem,

(1)

(1)

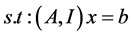

(2)

(2)

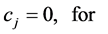

(3)

(3)

where  is an

is an  vector whose

vector whose  component is

component is  (where,

(where,

) and b is an

) and b is an  vector whose

vector whose  component is bi,

component is bi,  is an

is an  matrix, I is an

matrix, I is an  identity matrix and x is an

identity matrix and x is an  vector. Further assume that b and c are random vectors with joint density functions

vector. Further assume that b and c are random vectors with joint density functions  and

and  respectively. Next, consider the value of

respectively. Next, consider the value of  by first observing the vector b or the vector c and then solving (1)-(3). This paper is interested in finding explicit expressions for the distribution of

by first observing the vector b or the vector c and then solving (1)-(3). This paper is interested in finding explicit expressions for the distribution of ![]() if either b or c is random. This is called the distribution problem of stochastic linear programming.

if either b or c is random. This is called the distribution problem of stochastic linear programming.

Early work on the distribution problem can be found in Babbar [2] , Bereanu [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] , Hsia [8] , Prekopa [9] , Sengupta, Tintner, and Millham [10] , Sengupta, Tintner, and Morrison [11] , and Wets [12] . For additional references, see the bibliographies by Stancu-Minasian [13] and Van Der Vlerk [14] . Application of the distribution problem can be found in the areas of agriculture [15] and economic planning [10] , [11] . Explicit results for the distribution of ![]() are very difficult to obtain; indeed, most analyses rely on approximation techniques or simulation. (See, for example, Bracken and Soland [16] , Sarper [15] , or Dempster [17] ). Bereanu [3] discovered that under certain assumptions, the sample space of the random coefficients allows a partition into non-overlapping sets, called decision regions, such that a basis of the linear programming problem can be assigned to each of the sets, and this basis remains optimal for all of its sample points. Ewbank, et al. [1] extended this theory using a Jacobian transformation to simplify the computational analysis. To date, we believe that an explicit expression for the distribution of

are very difficult to obtain; indeed, most analyses rely on approximation techniques or simulation. (See, for example, Bracken and Soland [16] , Sarper [15] , or Dempster [17] ). Bereanu [3] discovered that under certain assumptions, the sample space of the random coefficients allows a partition into non-overlapping sets, called decision regions, such that a basis of the linear programming problem can be assigned to each of the sets, and this basis remains optimal for all of its sample points. Ewbank, et al. [1] extended this theory using a Jacobian transformation to simplify the computational analysis. To date, we believe that an explicit expression for the distribution of ![]() has only been obtained for stochastic b [1] , and no explicit results have been obtained for stochastic c. In addition, no explicit results have been obtained for non-exponential distributions. In this paper, we obtain new explicit results for exponential, uniform, gamma, and triangle distributions with b or c random. These are the first explicit results for the case in which c is random.

has only been obtained for stochastic b [1] , and no explicit results have been obtained for stochastic c. In addition, no explicit results have been obtained for non-exponential distributions. In this paper, we obtain new explicit results for exponential, uniform, gamma, and triangle distributions with b or c random. These are the first explicit results for the case in which c is random.

2. Theory

Following [1] , consider the linear programming problem (1)-(3). Let ![]() be the vector of basic variables corresponding to the ith basis, and

be the vector of basic variables corresponding to the ith basis, and ![]() is the

is the ![]() basis matrix whose columns are the columns of

basis matrix whose columns are the columns of ![]() corresponding to the elements of

corresponding to the elements of![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be the vector of coefficients of the basic variables in

be the vector of coefficients of the basic variables in ![]() basis and let

basis and let ![]() be the

be the ![]() column of

column of ![]() corresponding to

corresponding to![]() . Also,

. Also, ![]() and

and![]() .

. ![]() is an optimal basis if

is an optimal basis if

![]()

For all

![]() (4)

(4)

and is feasible if

![]() (5)

(5)

For the case in which the b vector is random, let the probability space be defined by the m-tuple![]() . Bereanu discovered that there exist non-overlapping regions

. Bereanu discovered that there exist non-overlapping regions

![]() (6)

(6)

where

![]() (7)

(7)

Thus,

![]() (8)

(8)

Now, let

![]()

Since

![]() (9)

(9)

Then

![]() (10)

(10)

![]() (11)

(11)

![]() (12)

(12)

Thus,

![]() (13)

(13)

Now, consider the case in which only the c vector is random. Let the probability space C be defined by the n-tuple![]() . Bereanu [3] found that the space C is partitioned by the sets:

. Bereanu [3] found that the space C is partitioned by the sets:

![]() (14)

(14)

where ![]() refers to the

refers to the ![]() basis. Further the set of points

basis. Further the set of points ![]() is of probability measure zero if the joint density function of

is of probability measure zero if the joint density function of ![]() is continuous. Points in this set are such that alternate optimal basis give the same value of

is continuous. Points in this set are such that alternate optimal basis give the same value of![]() . Also,

. Also,

![]() (15)

(15)

Thus,

![]() (16)

(16)

where ![]() is an arbitrary constant.

is an arbitrary constant.

To evaluate the right-hand side of equation Equation (15) let![]() . By definition

. By definition

![]() (17)

(17)

Since

![]() (18)

(18)

Then

![]() (19)

(19)

where

![]() (20)

(20)

Thus, if only the c vector is random the distribution function of ![]() can be found, in theory, by evaluating the integral in equation Equation (20). Given a basis Bi and sets

can be found, in theory, by evaluating the integral in equation Equation (20). Given a basis Bi and sets ![]() and

and![]() , the limits of the integral in Equation (12) and Equation (20) are the intersection of m or n hyperplanes (depending on whether the b vector or the c vector is stochastic). These limits are extremely difficult to obtain if the probability space has dimension greater than 3. Ewbank, et al., [1] developed a Jacobian transformation that greatly simplifies the computation of the integrals.

, the limits of the integral in Equation (12) and Equation (20) are the intersection of m or n hyperplanes (depending on whether the b vector or the c vector is stochastic). These limits are extremely difficult to obtain if the probability space has dimension greater than 3. Ewbank, et al., [1] developed a Jacobian transformation that greatly simplifies the computation of the integrals.

In the case of stochastic b, Let

![]() (21)

(21)

By substituting for b we have:

![]() (22)

(22)

The probability that a basis G remains feasible is

![]() (23)

(23)

where ![]() is the set of b’s defined in Equation (20), and by substituting Equation (21) in Equation (22), we have:

is the set of b’s defined in Equation (20), and by substituting Equation (21) in Equation (22), we have:

![]() (24)

(24)

where ![]() is the Jacobian

is the Jacobian

![]()

Because ![]() and

and![]() , this implies

, this implies

![]() (25)

(25)

Note that since

is the basis matrix, its determinant is nonzero; thus ![]() is also nonzero.

is also nonzero.

3. Computational Results

The problems were run using the Mathematica software version 8.0.1.0 utilizing the supercomputer at the University of Oklahoma.

CPUs: All compute nodes have dual Intel Xeon E5-2650 “Sandy Bridge” oct core 2.0 GHz CPUs; there is also one “fat node” with quad Intel Xeon E7-4830 “Westmere” oct core 2.13 GHz CPUs.

RAM: Most of the compute nodes have 32 GB of 1333 MHz RAM and 23 with 64 GB of 1333 MHz RAM; the one “fat node” has 1 TB of 1066 MHz RAM, which is called large memory.

Accelerators: There are 18 NVIDIA Tesla M2075 cards, for an aggregate of an additional approximately 9 TFLOPs double precision.

In order to compare the run times, four types of distributions were considered as shown in Table 1. The coefficients were randomly generated in small interval, because large intervals led to computational results that had results with coefficients of the orders of 1020 or larger.

3.1. Results for Stochastic b with Exponential Distribution

3.1.1. Problem 1

![]()

Table 1. Equations of distribution.

3.1.2. Problem 2

3.1.3. Problem 3

3.2. Results for Stochastic b with Uniform Distribution

3.2.1. Problem 1

3.2.2. Problem 2

3.2.3. Problem 3

3.3. Results for Stochastic b with Gamma Distribution

3.3.1. Problem 1

3.3.2. Problem 2

3.4. Results for Stochastic b with Triangle Distribution

Problem 1

3.5. Results for Stochastic c with Exponential Distribution

3.5.1. Problem 1

3.5.2. Problem 2

3.6. Results for Stochastic c with Uniform Distribution

3.6.1. Problem 1

3.6.2. Problem 2

3.7. Results for Stochastic c with Gamma Distribution

3.7.1. Problem 1

3.7.2. Problem 2

3.8. Results for Stochastic c with Triangle Distribution

3.8.1. Problem 1

3.8.2. Problem 2

4. Computational Time Comparisons

The different distributions were solved using both Bereanu’s method and the Ewbank, Foote and Kumin transformation method to compare the two. Table 2 and Table 3 compare the run times for both methods for case I and case II. The results show that

![]()

Table 2. Comparison between Bereanu and EFK method for case I.

![]()

Table 3. Comparison between Bereanu and EFK method for case II.

the EFK method substantially reduces the computational time. In addition, Bereanu’s method is not able to solve some larger sizes of the problem. All times are measured in seconds.