Modified Cp Criterion for Optimizing Ridge and Smooth Parameters in the MGR Estimator for the Nonparametric GMANOVA Model ()

1. Introduction

We consider the generalized multivariate analysis of variance (GMANOVA) model with observations of

observations of  -dimensional vectors of response variables. This model was proposed by [10]. Let

-dimensional vectors of response variables. This model was proposed by [10]. Let ,

,  ,

,  and

and  be an

be an  matrix of response variables, an

matrix of response variables, an  matrix of non-stochastic centerized between-individual explanatory variables (i.e.,

matrix of non-stochastic centerized between-individual explanatory variables (i.e., )

)

of

, a

, a  matrix of non-stochastic within-individual explanatory variables of

matrix of non-stochastic within-individual explanatory variables of

, and an

, and an  matrix of error variables, respectively, where

matrix of error variables, respectively, where is the sample size,

is the sample size,  is an

is an  -dimensional vector of ones and

-dimensional vector of ones and  is a

is a  -dimensional vector of zeros. Then, the GMANOVA model is expressed as

-dimensional vector of zeros. Then, the GMANOVA model is expressed as

where  is a

is a  unknown regression coefficient matrix an

unknown regression coefficient matrix an  is

is  -dimensional unknown vector. We assume that

-dimensional unknown vector. We assume that  where

where  is a

is a  unknown covariance matrix of

unknown covariance matrix of . Then we can express the GMANOVA model as

. Then we can express the GMANOVA model as

Let  be an unbiased estimator of the unknown covariance matrix

be an unbiased estimator of the unknown covariance matrix  that is given by

that is given by

Then, the maximum likelihood (ML) estimators of  and

and are given by

are given by and

and , respectively. The ML estimators are the unbiased and asymptotically efficiency estimators of

, respectively. The ML estimators are the unbiased and asymptotically efficiency estimators of  and

and .

.

In the GMANOVA model,  ,

,  is often used as the

is often used as the  th row vector of

th row vector of . Then, we estimate the longitudinal trends of

. Then, we estimate the longitudinal trends of  using

using  -polynomial curves. However, occasionally, the polynomial curve cannot thoroughly express flexible longitudinal trends. Hence, we consider estimating the longitudinal trends nonparametrically in the same manner as [11] and [5], i.e., we use the known basis function as

-polynomial curves. However, occasionally, the polynomial curve cannot thoroughly express flexible longitudinal trends. Hence, we consider estimating the longitudinal trends nonparametrically in the same manner as [11] and [5], i.e., we use the known basis function as  and assume that

and assume that  is large. In the present paper, we refer to the GMANOVA model with

is large. In the present paper, we refer to the GMANOVA model with  obtained from the basis function as the nonparametric GMANOVA model. In the nonparametric GMANOVA model, it is well known that the ML estimators become unstable because

obtained from the basis function as the nonparametric GMANOVA model. In the nonparametric GMANOVA model, it is well known that the ML estimators become unstable because  becomes unstable when

becomes unstable when  is large. Thus, we deal with the least square (LS) estimators of

is large. Thus, we deal with the least square (LS) estimators of  and

and , which are obtained by minimizing

, which are obtained by minimizing

. Then, the LS estimators of

. Then, the LS estimators of  and

and  are obtained by

are obtained by  and

and

respectively. Note that

respectively. Note that  does not depend on

does not depend on . The LS estimators are simple and unbiased estimators of

. The LS estimators are simple and unbiased estimators of  and

and . However, as well as ordinary nonparametric regression model, the LS estimators cause an overfitting problem when we use basis functions to estimate the longitudinal trends nonparametrically. In order to avoid the overfitting problem, we use

. However, as well as ordinary nonparametric regression model, the LS estimators cause an overfitting problem when we use basis functions to estimate the longitudinal trends nonparametrically. In order to avoid the overfitting problem, we use  instead of

instead of  as the penalized smoothing spline regression (see, e.g., [2]), where

as the penalized smoothing spline regression (see, e.g., [2]), where

is a smoothing parameter and

is a smoothing parameter and  is a

is a  known penalty matrix.

known penalty matrix.

Let , and let

, and let . Then, the GMANOVA model can be expressed as

. Then, the GMANOVA model can be expressed as

where  is the

is the  th element of

th element of . This expression indicates that the GMANOVA model is equivalent to the varying coefficient model with non-longitudinal covariates [13], i.e.,

. This expression indicates that the GMANOVA model is equivalent to the varying coefficient model with non-longitudinal covariates [13], i.e.,

(4)

(4)

where  and

and ,

, . Hence, estimating the longitudinal trends in the GMANOVA model nonparametrically is equivalent to estimating the varying coefficients

. Hence, estimating the longitudinal trends in the GMANOVA model nonparametrically is equivalent to estimating the varying coefficients ,

,  nonparametrically. However, when multicollinearity occurs in

nonparametrically. However, when multicollinearity occurs in , the estimate of

, the estimate of ,

,  becomes unstable, as does the ordinary LS estimator of regression coefficient, because the variance of an estimator of

becomes unstable, as does the ordinary LS estimator of regression coefficient, because the variance of an estimator of  becomes large. Hence, we avoid the multicollinearity problem in

becomes large. Hence, we avoid the multicollinearity problem in  by the ridge regression.

by the ridge regression.

When  and

and  in the model (1), [4] proposed a ridge regression. This estimator is generally defined by adding

in the model (1), [4] proposed a ridge regression. This estimator is generally defined by adding  to

to  in (3), where

in (3), where  is referred to as a ridge parameter. Since the ridge estimator changes with

is referred to as a ridge parameter. Since the ridge estimator changes with , optimization of

, optimization of  is very important. One method for optimizing

is very important. One method for optimizing  is minimizing the

is minimizing the  criterion proposed by [7,8] in the univariate linear regression model (for multivariate case, see e.g., [15]). For the case in which

criterion proposed by [7,8] in the univariate linear regression model (for multivariate case, see e.g., [15]). For the case in which  and

and , [17] proposed the

, [17] proposed the  and its bias-corrected

and its bias-corrected  (modified

(modified ;

; ) criteria for optimizing the ridge parameter. However, an optimal

) criteria for optimizing the ridge parameter. However, an optimal  cannot be obtained without an iterative computational algorithm because an optimal

cannot be obtained without an iterative computational algorithm because an optimal  cannot be obtained in closed form.

cannot be obtained in closed form.

On the other hand, [4] also proposed a generalized ridge (GR) regression in the univariate linear regression model, i.e., the model (1) with  and

and , simultaneously with the ridge regression. The GR estimator is defined not by a single ridge parameter, but rather by multiple ridge parameters

, simultaneously with the ridge regression. The GR estimator is defined not by a single ridge parameter, but rather by multiple ridge parameters ,

, . Then, several authors proposed a non-iterative GR estimator (see, e.g., [6]). [18] proposed a GR regression in the multivariate linear regression model, i.e., the model (1) with

. Then, several authors proposed a non-iterative GR estimator (see, e.g., [6]). [18] proposed a GR regression in the multivariate linear regression model, i.e., the model (1) with  and

and . We call this generalized ridge regression the multivariate GR (MGR) regression. They also proposed the

. We call this generalized ridge regression the multivariate GR (MGR) regression. They also proposed the  and

and  criteria for optimizing ridge parameters

criteria for optimizing ridge parameters  in the MGR regression. They showed that the optimized

in the MGR regression. They showed that the optimized  by minimizing two criteria are obtained in closed form. [9] proposed non-iterative MGR estimators by extending non-iterative GR estimators. Several computational tasks are required in estimating

by minimizing two criteria are obtained in closed form. [9] proposed non-iterative MGR estimators by extending non-iterative GR estimators. Several computational tasks are required in estimating  nonparametrically because we determine the optimal

nonparametrically because we determine the optimal  and the number of basis functions simultaneously. Fortunately, [18] reported that the performance of the MGR regression is the almost same as that of the multivariate ridge regression. Hence, we use the MGR regression in order to avoid the multicollinearity problem that occurs in

and the number of basis functions simultaneously. Fortunately, [18] reported that the performance of the MGR regression is the almost same as that of the multivariate ridge regression. Hence, we use the MGR regression in order to avoid the multicollinearity problem that occurs in  in order to reduce the number of computational tasks.

in order to reduce the number of computational tasks.

The remainder of the present paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, we propose new estimators using the concept of the penalized smoothing spline regression and the MGR regression. In Section 3, we show the target mean squared error (MSE) of a predicted value of . We then propose the

. We then propose the  and

and  criteria to optimize ridge parameters and smoothing parameter in the new estimator. Using these criteria, we show that the optimized ridge parameters are obtained in closed form under the fixed

criteria to optimize ridge parameters and smoothing parameter in the new estimator. Using these criteria, we show that the optimized ridge parameters are obtained in closed form under the fixed . We also show the magnitude relationship between the optimized ridge parameters. In Section 4, we compare the LS estimator in (3) with the proposed estimator through numerical studies. In Section 5, we present our conclusions.

. We also show the magnitude relationship between the optimized ridge parameters. In Section 4, we compare the LS estimator in (3) with the proposed estimator through numerical studies. In Section 5, we present our conclusions.

2. The New Estimators

In the model (1), we consider estimating the longitudinal trends nonparametrically by using basis functions . Then, we consider the following estimators in order to avoid the overfitting problem in the nonparametric GMANOVA model,

. Then, we consider the following estimators in order to avoid the overfitting problem in the nonparametric GMANOVA model,  and

and

(5)

(5)

where is a smoothing parameter and

is a smoothing parameter and  is a

is a  known penalty matrix. In this estimator, we must determine

known penalty matrix. In this estimator, we must determine  before using this estimator. Since

before using this estimator. Since  is usually set as some nonnegative definite matrix, we assume that

is usually set as some nonnegative definite matrix, we assume that is a nonnegative definite matrix. If

is a nonnegative definite matrix. If , where

, where is a

is a  matrix of zeros, then this estimator corresponds to the LS estimators

matrix of zeros, then this estimator corresponds to the LS estimators  and

and  in (1). Note that this estimator controls the smoothness of each estimated curve

in (1). Note that this estimator controls the smoothness of each estimated curve  and

and ,

,  through only one parameter

through only one parameter . When we use this estimator, we need to optimize the parameter

. When we use this estimator, we need to optimize the parameter because this estimator changes with

because this estimator changes with .

.

If multicollinearity occurs in , then the LS estimator

, then the LS estimator  in (1) and the proposed estimator

in (1) and the proposed estimator  in (5) are not good estimators in the sense of having large variance. Note that neither the LS estimator

in (5) are not good estimators in the sense of having large variance. Note that neither the LS estimator  nor the proposed estimator

nor the proposed estimator  depend on

depend on . Hence, we avoid the multicollinearity problem for estimating

. Hence, we avoid the multicollinearity problem for estimating . Multicollinearity often occurs when

. Multicollinearity often occurs when  becomes large. Using the following estimator, the multicollinearity problem in

becomes large. Using the following estimator, the multicollinearity problem in  can be avoided,

can be avoided,

(6)

(6)

where  is a ridge parameter. This estimator with

is a ridge parameter. This estimator with  corresponds to the estimator of [16]. If

corresponds to the estimator of [16]. If , then this estimator corresponds to the estimator in (5). Note that

, then this estimator corresponds to the estimator in (5). Note that  in this estimator corresponds to the ridge estimator for a multivariate linear model [17]. In this estimator, we need to optimize

in this estimator corresponds to the ridge estimator for a multivariate linear model [17]. In this estimator, we need to optimize  and

and  because this estimator changes with these parameters. However, we cannot obtain the optimized

because this estimator changes with these parameters. However, we cannot obtain the optimized  and

and  in closed form. Thus, we need to use an iterative computational algorithm to optimize two parameters. From another point of view, this estimator controls the smoothness of each estimated curve

in closed form. Thus, we need to use an iterative computational algorithm to optimize two parameters. From another point of view, this estimator controls the smoothness of each estimated curve ,

,  through only one parameter

through only one parameter . Hence, this estimator is not a well fitting curve when the smoothnesses of the true curves differ.

. Hence, this estimator is not a well fitting curve when the smoothnesses of the true curves differ.

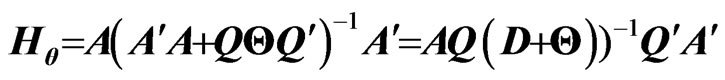

Hence, we apply the concept of the MGR estimator [18] to  in order to obtain the optimized ridge parameter in closed form. Here, we derive the MGR estimator for the nonparametric GMANOVA model as follows:

in order to obtain the optimized ridge parameter in closed form. Here, we derive the MGR estimator for the nonparametric GMANOVA model as follows:

(7)

(7)

where ,

, is also a ridge parameter,

is also a ridge parameter,  , and

, and  is the

is the  orthogonal matrix that diagonalizes

orthogonal matrix that diagonalizes , i.e.,

, i.e.,  where

where  and

and

are eigenvalues of

are eigenvalues of . It is clearly that

. It is clearly that ,

, . In this estimator, since

. In this estimator, since  shrinks the estimators of

shrinks the estimators of ,

,  to 0, we can regard

to 0, we can regard  as controlling the smoothness of

as controlling the smoothness of . Therefore, in this estimator, rough smoothness of the estimated curves is controlled by

. Therefore, in this estimator, rough smoothness of the estimated curves is controlled by , and each smoothness of

, and each smoothness of ,

,  is controlled by

is controlled by .

.

Clearly,  and

and . The

. The  with

with  for some

for some

corresponds to

corresponds to  in (6). Thus, the estimator

in (6). Thus, the estimator  includes these estimators. The estimator

includes these estimators. The estimator  is more flexible than these estimators

is more flexible than these estimators  and

and  because

because  has

has  parameters and

parameters and  or

or  has only one or two parameters. Hence, we consider

has only one or two parameters. Hence, we consider  and

and  in estimating the longitudinal trends or the varying coefficient curve, while avoiding the overfitting and multicollinearity problems in the nonparametric GMANOVA model. When

in estimating the longitudinal trends or the varying coefficient curve, while avoiding the overfitting and multicollinearity problems in the nonparametric GMANOVA model. When  and

and ,

,  corresponds to the MGR estimator in [18].

corresponds to the MGR estimator in [18].

3. Main Results

3.1. Target MSE

In order to define the MSE of the predicted value of , we prepare the following discrepancy function for measuring the distance between

, we prepare the following discrepancy function for measuring the distance between  matrices

matrices  and

and

:

:

Since  is an unknown covariance matrix, we use the unbiased estimator

is an unknown covariance matrix, we use the unbiased estimator  in (2) instead of

in (2) instead of  to estimate

to estimate . Hence, we estimate

. Hence, we estimate  using the following sample discrepancy function:

using the following sample discrepancy function:

(8)

(8)

These two functions,  and

and , correspond to the summation of the Mahalanobis distance and the sample Mahalanobis distance between the rows of

, correspond to the summation of the Mahalanobis distance and the sample Mahalanobis distance between the rows of  and

and , respectively. Clearly,

, respectively. Clearly,

and

and . Through simple calculation, we obtain the following properties:

. Through simple calculation, we obtain the following properties:

for any  matrices

matrices ,

,  and

and , Using the discrepancy function

, Using the discrepancy function , the MSE of the predicted value of

, the MSE of the predicted value of  is defined as

is defined as

(9)

(9)

where , which is the predicted value of

, which is the predicted value of  when we use

when we use  and

and  in (7). In the present paper, we regard

in (7). In the present paper, we regard  and

and  making the MSE the smallest as the principle optimum. However, we cannot use the MSE in (9) in actual application because this MSE includes unknown parameters. Hence, we must estimate (9) in order to estimate the optimum

making the MSE the smallest as the principle optimum. However, we cannot use the MSE in (9) in actual application because this MSE includes unknown parameters. Hence, we must estimate (9) in order to estimate the optimum  and

and .

.

3.2. The  and

and  Criteria

Criteria

Let and

and . Note that

. Note that . Hence, we obtain

. Hence, we obtain

From the properties of the function and using

and using , since

, since  is a nonstochastic variable and

is a nonstochastic variable and , and

, and  for any square matrix

for any square matrix , we obtain

, we obtain

Note that .Thus, we can calculate

.Thus, we can calculate  as follows:

as follows:

because ,

,  and

and  are non-stochastic variables. For calculating the expectations in the MSE, we prove the following lemma.

are non-stochastic variables. For calculating the expectations in the MSE, we prove the following lemma.

Lemma 3.1. For any  non-stochastic matrix

non-stochastic matrix , we obtain

, we obtain .

.

proof. Since , we obtain the

, we obtain the  th element of

th element of  as

as ,

,

. We obtain

. We obtain because

because

for any

for any  and

and  for any

for any , where

, where  is defined as

is defined as  if

if  and

and  if

if . Hence we obtain

. Hence we obtain

. This result means that

. This result means that  if

if  and

and  if

if . Thus, the lemma is proven.

. Thus, the lemma is proven.

Using this lemma, we obtain  and

and . Hence, we obtain

. Hence, we obtain

By replacing  with

with , we can propose the instinctive estimator of MSE, referred to as the

, we can propose the instinctive estimator of MSE, referred to as the  criterion, as follows:

criterion, as follows:

(10)

(10)

When we use this criterion, we optimize the ridge parameter  and the smoothing parameter

and the smoothing parameter  by the following algorithm:

by the following algorithm:

1) We obtain , where

, where

if

if  is given.

is given.

2) We obtain .

.

3) We obtain , where

, where

,

, under fixed

under fixed .

.

4) We optimize the ridge parameter and the smoothing parameter as  and

and , respectively.

, respectively.

Note that this  criterion corresponds to that in [18] when

criterion corresponds to that in [18] when  and

and .

.

There is some bias between the MSE in (9) and the  criterion in (10) because the

criterion in (10) because the  criterion is obtained by replacing

criterion is obtained by replacing in the MSE with

in the MSE with . Generally, when the sample size

. Generally, when the sample size  is small or the number of explanatory variables

is small or the number of explanatory variables  is large, this bias becomes large. Then, we cannot obtain the higher-accuracy estimation of the optimum parameters because we cannot obtain the higher-accuracy estimation of MSE of

is large, this bias becomes large. Then, we cannot obtain the higher-accuracy estimation of the optimum parameters because we cannot obtain the higher-accuracy estimation of MSE of  in (9). Hence, we correct the bias between

in (9). Hence, we correct the bias between  and the

and the  criterion. To correct the bias, we assume

criterion. To correct the bias, we assume .

.

Let and

and .

.

Note that and

and

because

because  and

and . Then, we obtain Since

. Then, we obtain Since ,

,

(see, e.g., [14]) and

(see, e.g., [14]) and

, we obtain

, we obtain

Therefore, we obtain the unbiased estimator for  as

as , where

, where . This implies that the bias corrected

. This implies that the bias corrected criterion, denoted as

criterion, denoted as  (modified

(modified ) criterion, is obtained by

) criterion, is obtained by

(11)

(11)

As in the case of using the , we optimize

, we optimize  and

and  using this criterion as follows:

using this criterion as follows:

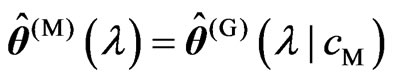

1) We obtain , where

, where ,

,

if

if  is given.

is given.

2) We obtain .

.

3) We obtain , where

, where

,

,  under fixed

under fixed .

.

4) We optimize the ridge parameter and the smoothing parameter as  and

and  , respectively.

, respectively.

Note that the  criterion corresponds to that in [18] when

criterion corresponds to that in [18] when  and

and . The

. The  criterion completely omits the bias between the MSE of

criterion completely omits the bias between the MSE of  in (9) and the

in (9) and the  criterion in (10) by using a number of constant terms

criterion in (10) by using a number of constant terms and

and . If

. If  and

and  can be expressed in closed form for any fixed

can be expressed in closed form for any fixed , we do not need the above iterative computational algorithm.

, we do not need the above iterative computational algorithm.

3.3. Optimizations using the  and

and Criteria

Criteria

Using the generalized

criterion, which is given in (14), we can express the

criterion, which is given in (14), we can express the  and

and  criteria as follows:

criteria as follows:

Note that the terms with respect to  in the

in the  and

and  criteria correspond to

criteria correspond to and

and , respectively. Hence, we consider obtaining the optimum

, respectively. Hence, we consider obtaining the optimum  by minimizing the

by minimizing the  criterion. From Theorem A, the optimum

criterion. From Theorem A, the optimum  is obtained in closed form as (15). Using the closed form in (15), we obtain

is obtained in closed form as (15). Using the closed form in (15), we obtain  and

and  for each

for each  and any fixed

and any fixed  as follows:

as follows:

(12)

(12)

(13)

(13)

where and

and are the

are the th elements of

th elements of and

and ,respectively,

,respectively, and

and . Note that

. Note that  and

and  vary with

vary with . Since

. Since  and

and  are regarded as a function of

are regarded as a function of , we can regard the

, we can regard the  and

and  criteria for optimizing

criteria for optimizing  and

and  in (10) and (11) as a function of

in (10) and (11) as a function of . This means that we can use these criteria to optimize

. This means that we can use these criteria to optimize .

.

Then, we can rewrite the optimization algorithms to optimize the ridge parameter  and the smoothing parameter

and the smoothing parameter by minimizing the

by minimizing the  and

and  criteria in (10) and (11) as follows:

criteria in (10) and (11) as follows:

1) We obtain and

and .

.

2) We optimize the ridge parameter and the smoothing parameter as  and

and , respectively, by using

, respectively, by using ,

,  and the closed forms in (12) and (13).

and the closed forms in (12) and (13).

This means that we can reduce the processing time to optimize the parameters, and we need to use the optimization algorithm for only one parameter,  , for any

, for any .

.

3.4. Magnitude Relationships between

Optimized Ridge Parameters

In this subsection, we prove the magnitude relationships between  and

and ,

, .

.

Lemma 3.2. For any , we obtain

, we obtain .

.

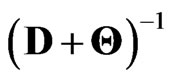

proof. Since we assume  as a nonnegative definite matrix, there exists

as a nonnegative definite matrix, there exists  that satisfies

that satisfies  (see, e.g., [3]). Then, since

(see, e.g., [3]). Then, since , we have

, we have

. Hence,

. Hence,  is a nonnegative definite matrix. This means that all of the eigenvalues of

is a nonnegative definite matrix. This means that all of the eigenvalues of  are nonnegative. Hence, all of the eigenvalues of

are nonnegative. Hence, all of the eigenvalues of  are nonnegative. Thus,

are nonnegative. Thus,  is also a nonnegative definite matrix for any

is also a nonnegative definite matrix for any . Since

. Since , we obtain

, we obtain  as a nonnegative definite matrix for any

as a nonnegative definite matrix for any . Thus, the lemma is proven.

. Thus, the lemma is proven.

Using the same idea, we have  for any

for any ,

, . Therefore, the final terms of the

. Therefore, the final terms of the  and

and  criteria in (10) and (11) are always greater than

criteria in (10) and (11) are always greater than . In order to prove the magnitude relationship between

. In order to prove the magnitude relationship between  and

and , we consider two situations in which

, we consider two situations in which  is satisfied and

is satisfied and  is satisfied.

is satisfied.

First, we consider  to be satisfied. Let

to be satisfied. Let

. Using

. Using , we obtain the following corollary:

, we obtain the following corollary:

Corollary 3.1. For any , we obtain

, we obtain

.

.

proof. Through simple calculation, we obtain

Since ,

,  and

and  from lemma 3.1, the corollary is proven.

from lemma 3.1, the corollary is proven.

This corollary indicates that  is satisfied when

is satisfied when  is satisfied because

is satisfied because , and

, and  is satisfied when

is satisfied when  is satisfied because

is satisfied because  and

and . Using these relationships, we obtain the following theorem.

. Using these relationships, we obtain the following theorem.

Theorem 3.1. For any , we obtain

, we obtain

.

.

proof. We consider the following situations:

1)  is satisfied

is satisfied

2)  is satisfied

is satisfied

3)  is satisfied.

is satisfied.

In (1),  , because

, because . In (3),

. In (3),  , because

, because  becomes

becomes . Hence, we only consider situation (2). Note that

. Hence, we only consider situation (2). Note that , because

, because  and

and . This means that

. This means that  does not become

does not become . This theorem holds when

. This theorem holds when , because, in this case,

, because, in this case,  and

and . We also consider

. We also consider  to be satisfied. Then, we obtain

to be satisfied. Then, we obtain

Since  is a positive definite matrix,

is a positive definite matrix,  for any

for any . From corollary 3.1, we have

. From corollary 3.1, we have for any

for any . Hence we obtain

. Hence we obtain  for any

for any since

since ,

,  and

and . Thus, this theorem is proven.

. Thus, this theorem is proven.

This theorem corresponds to that in [9] when  and

and .

.

From Theorem 3.1, we obtained the relationships between  and

and  for the case in which the optimized smoothing parameters

for the case in which the optimized smoothing parameters  and

and  are the same. However,

are the same. However,  and

and  are optimized by minimizing the

are optimized by minimizing the  and

and  criteria in (10) and (11). Hence,

criteria in (10) and (11). Hence,  and

and  are generally different. Thus, we consider the relationship between

are generally different. Thus, we consider the relationship between and

and  when

when . Since

. Since  is regarded as a function of

is regarded as a function of , we write

, we write  as

as  and

and  for each optimized smoothing parameter.

for each optimized smoothing parameter.

Theorem 3.2. We consider the following situations:

1)  or

or  is satisfied

is satisfied

2) and

and are satisfied

are satisfied

3)  is satisfied

is satisfied

4)  is satisfied

is satisfied

5)  or

or is satisfied.

is satisfied.

For any  and

and , we obtain the following relationships based on the above situations:

, we obtain the following relationships based on the above situations:

1) If (1), then

2) If (2) and (3), then

3) If (2) and (4), then

4) If (5), then .

.

proof. In (1) and (5), the relationships (i) and (iv) are true. Hence we need only prove relationships (ii) and (iii). Then we obtain  and

and  using the closed forms of (12) and (13). Through simple calculation, we obtain Since

using the closed forms of (12) and (13). Through simple calculation, we obtain Since  and the denominator is positive, the sign of

and the denominator is positive, the sign of  is the same as the sign of

is the same as the sign of . Hence we obtain relationships (ii) and (iii). Thus, the theorem is proven.

. Hence we obtain relationships (ii) and (iii). Thus, the theorem is proven.

4. Numerical Studies

In this section, we compare the LS estimator  and

and  in (3) with the proposed estimator

in (3) with the proposed estimator  and

and  in (7) through a numerical study. Let

in (7) through a numerical study. Let , and let

, and let  be an

be an  matrix as follows:

matrix as follows:

The explanatory matrix  is given by

is given by  where

where ,

,  is an

is an  matrix and each row vector of

matrix and each row vector of  is generated from the independent

is generated from the independent  -dimensional normal distribution with mean

-dimensional normal distribution with mean  and covariance matrix

and covariance matrix . Let

. Let ,

,  be a

be a  -dimensional vector. We set each

-dimensional vector. We set each  as follows:

as follows:

where  and the

and the th element of

th element of  is

is . Each element of

. Each element of  is Richard's growth curve model [12]. We set the longitudinal trends using these

is Richard's growth curve model [12]. We set the longitudinal trends using these  as

as . Note that

. Note that ,

, , which indicates that the last six rows of

, which indicates that the last six rows of are obtained by changing the scale of

are obtained by changing the scale of . The response matrix

. The response matrix  is generated by

is generated by  where

where . Then, we standardized

. Then, we standardized . Let

. Let ,

, and

and . We set each element of

. We set each element of  as a cubic

as a cubic  -spline basis function. Since

-spline basis function. Since  is set using the cubic

is set using the cubic  -spline, we note that

-spline, we note that . Additional details concerning

. Additional details concerning  and

and  are reported in [2]. We simulate

are reported in [2]. We simulate  repetitions for each

repetitions for each ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and . In each repetition, we fixed

. In each repetition, we fixed , but

, but  varies. We search

varies. We search and

and using fminsearch, which is a program in the software Matlab used to search for a minimum value, because

using fminsearch, which is a program in the software Matlab used to search for a minimum value, because  and

and  cannot be obtained in closed form. In searching

cannot be obtained in closed form. In searching  and

and , we transform

, we transform and search optimized

and search optimized by each criterion because

by each criterion because and

and . In the search algorithm, the starting point for the search is set as

. In the search algorithm, the starting point for the search is set as . Then, we obtain the optimized ridge parameters

. Then, we obtain the optimized ridge parameters  and

and using the closed forms of (12) and (13) in each repetition. In each repetition, we need to optimize

using the closed forms of (12) and (13) in each repetition. In each repetition, we need to optimize because

because and

and vary with

vary with . We calculate

. We calculate and

and for each

for each  in each repetition. Then, we adopt the optimized

in each repetition. Then, we adopt the optimized  by minimizing each criterion in each repetition. After that, we calculate for

by minimizing each criterion in each repetition. After that, we calculate for each criterion, where

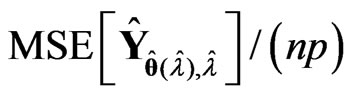

each criterion, where , which is obtained using

, which is obtained using  and

and  for each criterion and the optimized

for each criterion and the optimized  in each repetition. The average of

in each repetition. The average of  over

over  repetitions is regarded as the MSE of

repetitions is regarded as the MSE of . We compare the values predictedusing the estimators

. We compare the values predictedusing the estimators  and

and  with those using the LS estimators

with those using the LS estimators  and

and , and the estimators

, and the estimators  and

and  in (5). When we use

in (5). When we use , we obtain

, we obtain  by minimizing

by minimizing  and

and . As in the case of using

. As in the case of using , we adopt

, we adopt  by using each criterion in each repetition for

by using each criterion in each repetition for  and

and . Some of the results are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The values in the tables are obtained by

. Some of the results are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The values in the tables are obtained by ,

,

where

where ,and

,and

where

where .

.

Each estimator optimized by using the  criterion for

criterion for ,

,  , and

, and  is more improve than that by using the

is more improve than that by using the  criterion for each estimator in almost all situations. This indicates that the

criterion for each estimator in almost all situations. This indicates that the  criterion is a better estimator of the MSE of each predicted value of

criterion is a better estimator of the MSE of each predicted value of  than the

than the  criterion. The reasons for this are that the

criterion. The reasons for this are that the  criterion is an unbiased estimator of MSE

criterion is an unbiased estimator of MSE

Table 1. MSE when is selected using each criterion for each method in each repetition

is selected using each criterion for each method in each repetition .

.

Table 2. MSE when is selected using each criterion for each method in each repetition

is selected using each criterion for each method in each repetition .

.

and each of the parameters in each estimator is optimized by minimizing the  criterion. When

criterion. When ,

,  provides a greater improvement than either

provides a greater improvement than either  or

or  in all situations. The estimator

in all situations. The estimator , which is optimized using the

, which is optimized using the  criterion, has the smallest MSE among these estimators for almost situations when

criterion, has the smallest MSE among these estimators for almost situations when . Here,

. Here,  provides a greater improvement than

provides a greater improvement than  when

when  in all situations. When

in all situations. When  is large, the estimator

is large, the estimator  provides a greater improvement than

provides a greater improvement than  in most situations when

in most situations when . On the other hand,

. On the other hand,  provides a greater improvement than

provides a greater improvement than  in most situations when

in most situations when  is small,

is small,  and

and . If

. If , then

, then  and

and  improve the LS estimator. Comparing the results for

improve the LS estimator. Comparing the results for  with the results for

with the results for  reveals that these estimators become poor esti mators when

reveals that these estimators become poor esti mators when  becomes large. The reasons for this are thought to be that

becomes large. The reasons for this are thought to be that  and

and  become unstable and the

become unstable and the  has some curves that are in a different scale. Each MSE using each method and the

has some curves that are in a different scale. Each MSE using each method and the  criterion is similar to that using the

criterion is similar to that using the  criterion if

criterion if  becomes large because

becomes large because  is close to 1. When

is close to 1. When  becomes large,

becomes large,  improves the LS estimator more than when

improves the LS estimator more than when  is small. Since

is small. Since  controls the correlation in

controls the correlation in , the multicollinearity in

, the multicollinearity in  becomes large when

becomes large when  becomes large. Then,

becomes large. Then,  is not a good estimator because

is not a good estimator because  is unstable. Hence, we can avoid the multicollinearity problem in

is unstable. Hence, we can avoid the multicollinearity problem in  by using

by using , which is one of the purposes of the present study. In all situations, the new estimators improve the LS estimator

, which is one of the purposes of the present study. In all situations, the new estimators improve the LS estimator . In addition,

. In addition,  is better than

is better than  in most situations, especially when

in most situations, especially when  is small or

is small or  is large. In general,

is large. In general,  optimized using

optimized using  is the best method.

is the best method.

5. Conclusions

In the present paper, we estimate the longitudinal trends nonparametrically by using the nonparametric GMANOVA model in (1), which is defined using basis functions as  in the GMANOVA model. When we use basis functions as

in the GMANOVA model. When we use basis functions as , the LS estimators

, the LS estimators  and

and  incur overfitting. In order to avoid this problem, we proposed

incur overfitting. In order to avoid this problem, we proposed  and

and  in (5) using the smoothing parameter

in (5) using the smoothing parameter

and the

and the  known penalty non-negative definite matrix

known penalty non-negative definite matrix . However, if multicollinearity occurs in

. However, if multicollinearity occurs in ,

,  and

and  are not good estimators due to large variance. In the present paper, we also proposed

are not good estimators due to large variance. In the present paper, we also proposed  in (7) in order to avoid the multicollinearity problem that occurs in

in (7) in order to avoid the multicollinearity problem that occurs in  and the overfitting problem by using basis functions as

and the overfitting problem by using basis functions as . The estimator

. The estimator  controls the smoothness of each estimated longitudinal curve using only one parameter

controls the smoothness of each estimated longitudinal curve using only one parameter . On the other hand, in the estimator

. On the other hand, in the estimator , the rough smoothness of estimated longitudinal curves is controlled using

, the rough smoothness of estimated longitudinal curves is controlled using , and each smoothness of

, and each smoothness of

in the varying coefficient model (4) is controlled by

in the varying coefficient model (4) is controlled by .

.

We also proposed the  and

and  criteria in (10) and (11) for optimizing the ridge parameter

criteria in (10) and (11) for optimizing the ridge parameter  and the smoothing parameter

and the smoothing parameter . Then, using the

. Then, using the  criterion in (14) and minimizing this criterion in Theorem A, we obtain the optimized

criterion in (14) and minimizing this criterion in Theorem A, we obtain the optimized  using the

using the  and

and  criteria in closed form as (12) and (13) for any

criteria in closed form as (12) and (13) for any . Thus, we can regard the

. Thus, we can regard the  and

and  criteria as a function of

criteria as a function of .

.

Hence, we need to optimize only one parameter  in order to optimize

in order to optimize  parameters in

parameters in  using these criteria. On the other hand, we must optimize two parameters when we use

using these criteria. On the other hand, we must optimize two parameters when we use  in (6). This optimization is difficult and requires a complicated program and a long processing time for simulation or analysis of real data because the optimized

in (6). This optimization is difficult and requires a complicated program and a long processing time for simulation or analysis of real data because the optimized  cannot be obtained in closed form even if

cannot be obtained in closed form even if  is fixed. This is the advantage of using

is fixed. This is the advantage of using . This advantage does not appear to be important because of the high calculation power of CPUs. However, this advantage is made clear when we use

. This advantage does not appear to be important because of the high calculation power of CPUs. However, this advantage is made clear when we use  together with variable selection. Even if

together with variable selection. Even if  becomes large, then this advantage remains when

becomes large, then this advantage remains when  is used because the optimized

is used because the optimized  obtained using each criterion is always obtained as (12) and (13) for any

obtained using each criterion is always obtained as (12) and (13) for any . Furthermore, we must optimize

. Furthermore, we must optimize  if we use model (1) to estimate the longitudinal trends. This means that we optimize the parameters in the estimators and calculate the valuation of the estimator for each

if we use model (1) to estimate the longitudinal trends. This means that we optimize the parameters in the estimators and calculate the valuation of the estimator for each , and then we compare these values in order to optimize

, and then we compare these values in order to optimize . Since this optimization requires an iterative computational algorithm, we must reduce the processing time for estimating the parameters in the estimator. Hence, the advantage of using

. Since this optimization requires an iterative computational algorithm, we must reduce the processing time for estimating the parameters in the estimator. Hence, the advantage of using  is very important. This optimized ridge parameter in (12) and (13) corresponds to that in [18] when

is very important. This optimized ridge parameter in (12) and (13) corresponds to that in [18] when  and

and

.

.

Using some matrix properties, we showed that  and

and  in the

in the  and

and  criteria are always nonnegative. From

criteria are always nonnegative. From  for any

for any  in lemma 3.1, we also established the relationship between

in lemma 3.1, we also established the relationship between  and

and  for any

for any  in corollary 3.1. Then, in Theorem 3.1, we established the relationship between

in corollary 3.1. Then, in Theorem 3.1, we established the relationship between  and

and  if

if  and

and  are the same, where

are the same, where  and

and  are obtained by minimizing the

are obtained by minimizing the  and

and  criteria. Note that this relationship corresponds to that in [9] when

criteria. Note that this relationship corresponds to that in [9] when  and

and . In Theorem 3.2, we also established the relationships between

. In Theorem 3.2, we also established the relationships between  and

and  for the more general case, in which

for the more general case, in which  and

and  are different. The reason of the relationship in Theorem 3.2 is occurred is that

are different. The reason of the relationship in Theorem 3.2 is occurred is that  and

and  for each

for each  can be regarded as a function of

can be regarded as a function of .

.

The numerical results reveal that  and

and  have some following properties. These estimation methods

have some following properties. These estimation methods  and

and  improve the LS estimator in all situations, especially when

improve the LS estimator in all situations, especially when  is large. This indicates that the proposed estimators are better than the LS estimator. Even if

is large. This indicates that the proposed estimators are better than the LS estimator. Even if  becomes large, we note that

becomes large, we note that  is stable because we add the ridge parameter to

is stable because we add the ridge parameter to  in the LS estimator. This result indicates that the multicollinearity problem in

in the LS estimator. This result indicates that the multicollinearity problem in  can be avoided by using the estimator in (7). These estimators can be used to estimate the true longitudinal trends nonparametrically using basis functions as

can be avoided by using the estimator in (7). These estimators can be used to estimate the true longitudinal trends nonparametrically using basis functions as  without overfitting. The LS estimator and the proposed estimators

without overfitting. The LS estimator and the proposed estimators  and

and  optimized using the

optimized using the  criterion provide a greater improvement than the estimators optimized using the

criterion provide a greater improvement than the estimators optimized using the  criterion in most situations. The reason for this is that the

criterion in most situations. The reason for this is that the  criterion is the unbiased estimator of MSE of the predicted value of

criterion is the unbiased estimator of MSE of the predicted value of . Based on the present numerical study,

. Based on the present numerical study,  and

and  can be used to estimate the longitudinal trends in most situations. In addition, the

can be used to estimate the longitudinal trends in most situations. In addition, the  can be used to optimize the smoothing parameter

can be used to optimize the smoothing parameter  and the number of basis functions

and the number of basis functions . Hence, we can use

. Hence, we can use  and

and , the parameters

, the parameters ,

,  , and

, and  of which are optimized by the

of which are optimized by the  criterion for estimating the longitudinal trends.

criterion for estimating the longitudinal trends.

6. Acknowledgments

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Dr. Hirokazu Yanagihara of Hiroshima University for his valuable ideas and useful discussions. In addition, I would like to thank Prof. Yasunori Fujikoshi, Prof. Hirofumi Wakaki, Dr. Kenichi Satoh and Dr. Kengo Kato of Hiroshima University for their useful suggestions and comments. Finally, I would like to thank Dr. Tomoyuki Akita of Hiroshima University for his advice with regard to programming.

7. Appendix

7.1. Minimization of the  Criterion

Criterion

In this appendix, we show that the optimizations using the  and

and  criteria in (10) and (11) are obtained in closed form as (12) and (13) for any

criteria in (10) and (11) are obtained in closed form as (12) and (13) for any

. [9] proposed the generalized

. [9] proposed the generalized

criterion for the MGR regression (originally the

criterion for the MGR regression (originally the  criterion for selection variables in the univariate regression was proposed by [1]). Similar to their idea, we proposed the

criterion for selection variables in the univariate regression was proposed by [1]). Similar to their idea, we proposed the  criterion for the nonparametric GMANOVA model.

criterion for the nonparametric GMANOVA model.

By omitting constant terms and some terms with respect to  in the

in the  and

and  criteria in (10) and (11), these criteria are included in a class of criteria specified by

criteria in (10) and (11), these criteria are included in a class of criteria specified by

. This class is expressed by the

. This class is expressed by the criterion as

criterion as

(14)

(14)

where the function  is given by (8). Note that

is given by (8). Note that  and

and  correspond to the terms with respect to

correspond to the terms with respect to  in the

in the  and

and  criteria. Using this

criteria. Using this  criterion, we can deal systematically with the

criterion, we can deal systematically with the  and

and  criteria for optimizing

criteria for optimizing . Let

. Let ,

, which minimize the

which minimize the  criterion for any

criterion for any

. Then,

. Then,  and

and  are obtained as

are obtained as and

and , respectively. Thus, we can deal systematically with the optimizations of

, respectively. Thus, we can deal systematically with the optimizations of  when we use the

when we use the  and

and  criteria. This means that we need only obtain

criteria. This means that we need only obtain  in order to obtain

in order to obtain  and

and  for any

for any and some

and some . If

. If  is obtained in closed form for any fixed

is obtained in closed form for any fixed , we do not need to use the iterative computational algorithm for optimizing the ridge parameter

, we do not need to use the iterative computational algorithm for optimizing the ridge parameter . In order to obtain

. In order to obtain , we obtain

, we obtain ,

,  in closed form, as shown in the following theorem.

in closed form, as shown in the following theorem.

Theorem A. For any  and

and

,

,  is obtained as

is obtained as

(15)

(15)

where .

.

proof. Since  and we use the

and we use the

properties of the function  in Section 3.1, we can calculate

in Section 3.1, we can calculate  in the

in the  criterion in (14) as follows:

criterion in (14) as follows:

Since for any

for any ,

,  and

and  for any

for any , the second term in the right-hand side of the above equation can be calculated as Note that

, the second term in the right-hand side of the above equation can be calculated as Note that because

because  is an orthogonal matrix and

is an orthogonal matrix and . Hence, we obtain the following results:

. Hence, we obtain the following results:

Since  and

and  are diagonal matrices, we obtain

are diagonal matrices, we obtain . Hence

. Hence  is calculated as

is calculated as

where and

and . Clearly,

. Clearly,  and

and  change with

change with . Based on this result and

. Based on this result and , we can calculate the

, we can calculate the  criterion in (14) as follows:

criterion in (14) as follows:

Then, we calculate the second and third terms in the right-hand side of the above equation as follows:

where  and

and  are the

are the  th element of

th element of  and

and , respectively. Clearly,

, respectively. Clearly,  and

and  also vary with

also vary with . Note that

. Note that ,

,  for any

for any  because

because  is a positive definite matrix (see, e.g., [3]). Let

is a positive definite matrix (see, e.g., [3]). Let ,

,  be as follows:

be as follows:

(16)

(16)

Using , we can express

, we can express

Since  does not depend on

does not depend on , we can obtain

, we can obtain  by minimizing

by minimizing  for each

for each  and any

and any

. In order to obtain

. In order to obtain , we consider the following function for

, we consider the following function for :

:

(17)

(17)

If we restrict  to be greater than or equal to 0, then this function is equivalent to the function

to be greater than or equal to 0, then this function is equivalent to the function  in (16), which must be minimized. Note that

in (16), which must be minimized. Note that  and

and . Letting

. Letting , we obtain

, we obtain

Let  satisfy

satisfy  and

and , then

, then  is obtained by

is obtained by

where . Note that

. Note that  in (17) has a minimum value at

in (17) has a minimum value at , which is

, which is  and

and . Note that the sign of

. Note that the sign of  is the same as the sign of

is the same as the sign of . In order to obtain

. In order to obtain

, we consider the following situations:

, we consider the following situations:

1)  is satisfied

is satisfied

2)  and

and  are satisfied

are satisfied

3)  and

and  are satisfied.

are satisfied.

In (1),  , because

, because  and

and . In addition,

. In addition,  for any

for any , because

, because , and

, and  indicates that the sign of

indicates that the sign of  is nonnegative. This means that the minimum value of

is nonnegative. This means that the minimum value of  in

in  is obtained when

is obtained when  in situation (1). In (2),

in situation (1). In (2),  , and then the minimum value of

, and then the minimum value of  in

in  is obtained when

is obtained when . In (3), since

. In (3), since  and

and , we obtain

, we obtain

for any

for any . Hence,

. Hence,  is minimized when

is minimized when  in

in . From the above results, we obtain

. From the above results, we obtain

as follows:

as follows:

Thus, the theorem is proven.

Note that  corresponds to that in [9] when

corresponds to that in [9] when  and

and . Since we obtain

. Since we obtain  and

and  in closed form as (15) for any

in closed form as (15) for any , we must optimize only one parameter

, we must optimize only one parameter  in order to optimize

in order to optimize  parameters. The use of

parameters. The use of  is advantageous because only an iterative computational algorithm is required for optimizing only one parameter

is advantageous because only an iterative computational algorithm is required for optimizing only one parameter  for any

for any . This means that we can reduce the processing time required to optimize the parameters in the estimator

. This means that we can reduce the processing time required to optimize the parameters in the estimator  which is defined by (7). When we use

which is defined by (7). When we use  in (5), we also need the same iterative computational algorithm to optimize only one parameter

in (5), we also need the same iterative computational algorithm to optimize only one parameter .

.

On the other hand, when we use  in (6), the

in (6), the  criterion for optimizing

criterion for optimizing  for any fixed

for any fixed  is obtained as

is obtained as

Since we need to minimize  in order to optimize

in order to optimize , we cannot obtain

, we cannot obtain  that minimizes this

that minimizes this  criterion for

criterion for  in closed form, even if

in closed form, even if  is fixed. Thus, we use an iterative computational algorithm to optimize the parameters

is fixed. Thus, we use an iterative computational algorithm to optimize the parameters  and

and  simultaneously. This iterative computational algorithm for optimizing two parameters is difficult and requires a longer processing time than the optimization of a single parameter

simultaneously. This iterative computational algorithm for optimizing two parameters is difficult and requires a longer processing time than the optimization of a single parameter

[1] A. C. Atkinson, “A note on the generalized information criterion for choice of a model,” Biometrika, vol. 67, no. 2, March 1980, pp. 413-418., pp. 291-293.

[2] P. J. Green and B. W. Silverman, “Nonparametric Regression and Generalized Linear Models,” Chapman & Hall/CRC, 1994.

[3] D. A. Harville, “Matrix Algebra from a Statistician’s Perspective,” New York Springer, 1997.

[4] A. E. Hoerl and R. W. Kennard, “Ridge regression: biased estimation for nonorthogonal problems,” Technometrics, vol. 12, No. 1, February 1970, pp. 55-67.

[5] A. M. Kshirsagar and W. B. Smith, “Growth Curves,” Marcel Dekker, 1995.

[6] J. F. Lawless, “Mean squared error properties of generalized ridge regression,” Journal of the American Statistical Association, vol. 76, no. 374, 1981, pp. 462-466.

[7] C. L. Mallows, “Some comments on Cp,” Technometrics, vol. 15, no. 1, November 1973, pp. 661-675.

[8] C. L. Mallows, “More comments on Cp,” Technometrics, vol. 37, no. 4, November 1995, pp. 362-372.

[9] I. Nagai, H. Yangihara and K. Satoh, “Optimization of Ridge Parameters in Multivariate Generalized Ridge Regression by Plug-in Methods,” TR 10-03, Statistical Research Group, Hiroshima University, 2010.

[10] R. F. Potthoff and S. N. Roy, “A generalized multivariate analysis of variance model useful especially for growth curve problems,” Biometrika, vol. 51, no. 3–4, December 1964, pp. 313-326.

[11] K. S. Riedel and K. Imre, “Smoothing spline growth curves with covariates,” Communications in Statistics – Theory and Methods, vol. 22, no. 7, 1993, pp. 1795-1818.

[12] F. J. Richard, “A flexible growth function for empirical use,” Journal of Experimental Botany, vol. 10, no. 2, 1959, pp. 290–301.

[13] K. Satoh and H. Yanagihara, “Estimation of varying coefficients for a growth curve model,” American Journal of Mathematical and Management Sciences, 2010 (in press).

[14] M. Siotani, T. Hayakawa and Y. Fujikoshi, “Modern Multivariate Statistical Analysis: A Graduate Course and Handbook,” American Sciences Press, Columbus, Ohio, 1985.

[15] R. S. Sparks, D. Coutsourides and L. Troskie, “The multivariate ,” Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods, vol. 12, no. 15, 1983, pp. 1775-1793.

,” Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods, vol. 12, no. 15, 1983, pp. 1775-1793.

[16] Y. Takane, K. Jung and H. Hwang, “Regularized reduced rank growth curve models,” Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, vol. 55, no. 2, February 2011, pp. 1041-1052.

[17] H. Yanagihara and K. Satoh, “An unbiased Cp criterion for multivariate ridge regression,” Journal of Multivariate Analysis, vol. 101, no. 5, May 2010, pp. 1226-1238.

[18] H. Yanagihara, I. Nagai and K. Satoh, “A bias-corrected Cp criterion for optimizing ridge parameters in multivariate generalized ridge regression,” Japanese Journal of Applied Statistics, vol. 38, no. 3, October 2009, pp. 151-172 (in Japanese).