1. Introduction

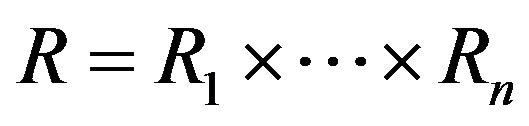

Let R be a commutative ring with non-zero identity and let  be the set of zero-divisors of R. For an arbitrary subset A of R, we put

be the set of zero-divisors of R. For an arbitrary subset A of R, we put . The zero-divisor graph of R, denoted by

. The zero-divisor graph of R, denoted by , is an undirected graph whose vertices are elements of

, is an undirected graph whose vertices are elements of  with two distinct vertices a and b are adjacent if and only if ab = 0.

with two distinct vertices a and b are adjacent if and only if ab = 0.

The concept of zero-divisor graph of a commutative ring was introduced by Beck [1], but this work was mostly concerned with colorings of rings. The above definition first appeared in Anderson and Livingston [2], which contained several fundamental results concerning the graph . The zero-divisor graphs of commutative rings have been studied by several authors. For instance, the preservation and lack thereof of basic properties of

. The zero-divisor graphs of commutative rings have been studied by several authors. For instance, the preservation and lack thereof of basic properties of  under extensions to rings of polynomials and power series was studied by Axtell, Coykendall and Stickles in [3] and Lucas in [4]. Also Axtell, Stickles and Warfel in [5], considered the zero-divisor graphs of direct products of commutative rings.

under extensions to rings of polynomials and power series was studied by Axtell, Coykendall and Stickles in [3] and Lucas in [4]. Also Axtell, Stickles and Warfel in [5], considered the zero-divisor graphs of direct products of commutative rings.

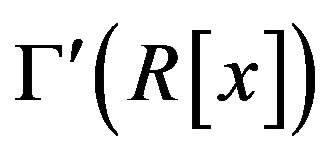

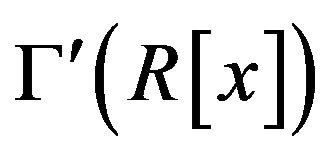

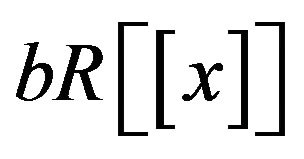

Let  be the set of all non-unit elements of R. For an arbitrary commutative ring R, the cozero-divisor graph of R, denoted by

be the set of all non-unit elements of R. For an arbitrary commutative ring R, the cozero-divisor graph of R, denoted by , was introduced in [6], which is a dual of zero-divisor graph

, was introduced in [6], which is a dual of zero-divisor graph  “in some sense”. The vertex-set of

“in some sense”. The vertex-set of  is

is  and for two distinct vertices a and b in

and for two distinct vertices a and b in , a is adjacent to b if and only if

, a is adjacent to b if and only if  and

and , where cR is an ideal generated by the element c in R. Some basic results on the structure of this graph and the relations between two graphs

, where cR is an ideal generated by the element c in R. Some basic results on the structure of this graph and the relations between two graphs  and

and  were studied in [6].

were studied in [6].

In this paper, we study the cozero-divisor graphs of the rings of polynomials, power series and the direct product of two arbitrary commutative rings. Also, we look at the preservation of the diameter and girth of the cozero-divisor graphs in some extension rings. Our results “in some sense” are the dual of the main results of [3-5].

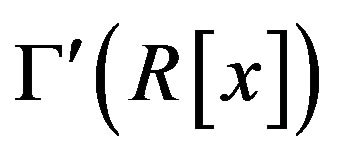

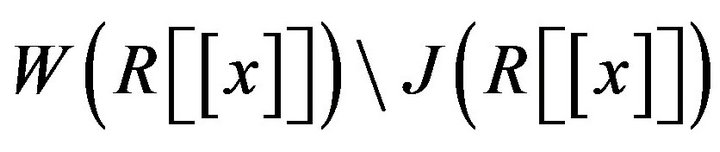

Throughout the paper, R is a commutative ring with non-zero identity. We denote the set of maximal ideals and the Jacobson radical of R by  and

and , respectively. Also,

, respectively. Also,  is the set of all unit elements of R. By a local ring, we mean a (not necessarily Noetherian) ring with a unique maximal ideal.

is the set of all unit elements of R. By a local ring, we mean a (not necessarily Noetherian) ring with a unique maximal ideal.

In a graph G, the distance between two distinct vertices a and b, denoted by , is the length of the shortest path connecting a and b, if such a path exists; otherwise, we set

, is the length of the shortest path connecting a and b, if such a path exists; otherwise, we set . The diameter of a graph G is

. The diameter of a graph G is

The girth of G, denoted by , is the length of the shortest cycle in G, if G contains a cycle; otherwise,

, is the length of the shortest cycle in G, if G contains a cycle; otherwise, . Also, for two distinct vertices a and b in G, the notation

. Also, for two distinct vertices a and b in G, the notation  means that a and b are adjacent. A graph G is said to be connected if there exists a path between any two distinct vertices, and it is complete if it is connected with diameter one. We use

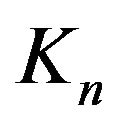

means that a and b are adjacent. A graph G is said to be connected if there exists a path between any two distinct vertices, and it is complete if it is connected with diameter one. We use  to denote the complete graph with n vertices. Moreover, we say that G is totally disconnected if no two vertices of G are adjacent. For a graph G, let

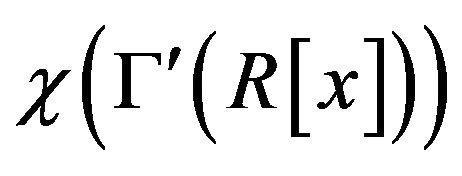

to denote the complete graph with n vertices. Moreover, we say that G is totally disconnected if no two vertices of G are adjacent. For a graph G, let  denote the chromatic number of the graph G, i.e., the minimal number of colors which can be assigned to the vertices of G in such a way that any two adjacent vertices have different colors. A clique of a graph is any complete subgraph of the graph and the number of vertices in a largest clique of G, denoted by

denote the chromatic number of the graph G, i.e., the minimal number of colors which can be assigned to the vertices of G in such a way that any two adjacent vertices have different colors. A clique of a graph is any complete subgraph of the graph and the number of vertices in a largest clique of G, denoted by , is called the clique number of G. Obviously

, is called the clique number of G. Obviously  (cf. see [7, p. 289]). For a positive integer r, an r-partite graph is one whose vertex-set can be partitioned into r subsets so that no edge has both ends in any one subset. A complete r-partite graph is one in which each vertex is joined to every vertex that is not in the same subset. The complete bipartite graph (2-partite graph) with subsets containing m and n vertices, respectively, is denoted by

(cf. see [7, p. 289]). For a positive integer r, an r-partite graph is one whose vertex-set can be partitioned into r subsets so that no edge has both ends in any one subset. A complete r-partite graph is one in which each vertex is joined to every vertex that is not in the same subset. The complete bipartite graph (2-partite graph) with subsets containing m and n vertices, respectively, is denoted by . A graph is said to be planar if it can be drawn in the plane so that its edges intersect only at their ends. A subdivision of a graph is any graph that can be obtained from the original graph by replacing edges by paths. A remarkable simple characterization of the planar graphs was given by Kuratowski in 1930. Kuratowski’s Theorem says that a graph is planar if and only if it contains no subdivision of

. A graph is said to be planar if it can be drawn in the plane so that its edges intersect only at their ends. A subdivision of a graph is any graph that can be obtained from the original graph by replacing edges by paths. A remarkable simple characterization of the planar graphs was given by Kuratowski in 1930. Kuratowski’s Theorem says that a graph is planar if and only if it contains no subdivision of  or

or  (cf. [8, p. 153]). Also, the valency of a vertex a is the number of edges of the graph G incident with a.

(cf. [8, p. 153]). Also, the valency of a vertex a is the number of edges of the graph G incident with a.

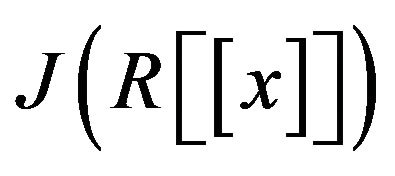

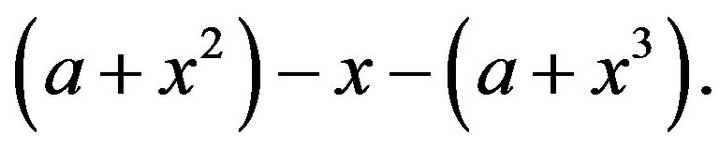

2. Cozero-Divisor Graph of

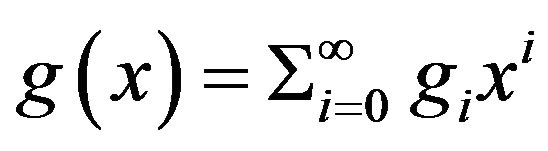

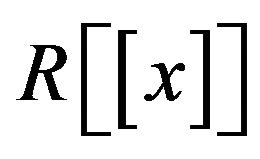

In this section, we are going to study some basic properties of the cozero-divisor graph of the polynomial ring . To this end, we first gather together the wellknown properties of the polynomial ring

. To this end, we first gather together the wellknown properties of the polynomial ring , which are needed in this section.

, which are needed in this section.

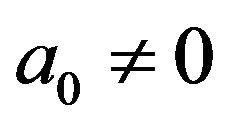

Remarks 2.1 Let  be an arbitrary element in

be an arbitrary element in . Then we have the following statements:

. Then we have the following statements:

•  is a unit in

is a unit in  if and only if a0 is a unit and the coefficients

if and only if a0 is a unit and the coefficients  are nilpotent elements of R.

are nilpotent elements of R.

•  is nilpotent if and only if the coefficients

is nilpotent if and only if the coefficients  are nilpotent.

are nilpotent.

•  , where

, where  is the nilradical of

is the nilradical of .

.

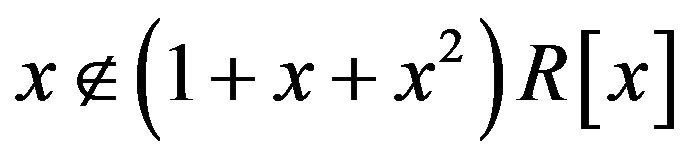

• Since the polynomials x and 1 + x are non-units,  is a non-local ring.

is a non-local ring.

• By part (i), it is easy to see that  is an induced subgraph of

is an induced subgraph of .

.

In the following theorem, we show that  is always connected and its diameter is not exceeding three.

is always connected and its diameter is not exceeding three.

Theorem 2.2 The graph  is connected and

is connected and .

.

Proof. Since  is a non-local ring, by [1, Theorem 2.5], it is enough to show that, for every non-zero element

is a non-local ring, by [1, Theorem 2.5], it is enough to show that, for every non-zero element , there exist

, there exist  and

and  such that

such that . Now, assume that

. Now, assume that  is a non-zero polynomial in

is a non-zero polynomial in  of degree t. Since x is a non-unit element in

of degree t. Since x is a non-unit element in , there exists a maximal ideal m of

, there exists a maximal ideal m of  such that

such that . So

. So . On the other hand, by parts (ii) and (iii) of Remarks 2.1,

. On the other hand, by parts (ii) and (iii) of Remarks 2.1, . Also

. Also  . Hence the graph

. Hence the graph  is connected and

is connected and .

.

The following proposition states that the diameter of  is never one.

is never one.

Proposition 2.3 The graph  is never complete.

is never complete.

Proof. Clearly  and

and . The claim now follows from [1, Theorem 2.1].

. The claim now follows from [1, Theorem 2.1].

The following corollary is an immediate consequence of Theorem 2.2 and Proposition 2.3.

Corollary 2.4  or 3.

or 3.

Proposition 2.5 Suppose that . Then

. Then

. In particular, if R is reduced, then

. In particular, if R is reduced, then

.

.

Proof. In view of [1, Corollary 2.4],

. Now, by Proposition 2.3, one can conclude that

. Now, by Proposition 2.3, one can conclude that . Also, if R is reduced, then by Remarks 2.1 (ii),

. Also, if R is reduced, then by Remarks 2.1 (ii),  and so, by Remarks 2.1 (iii),

and so, by Remarks 2.1 (iii), .

.

In the next two theorems, we investigate the girth of the graph .

.

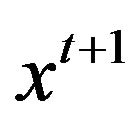

Theorem 2.6 Suppose that R is a non-reduced ring. Then every element of  is in a cycle of length three.

is in a cycle of length three.

Proof. Assume that  is a non-zero element in

is a non-zero element in  of degree n and consider the elements

of degree n and consider the elements  and

and  in

in , where

, where . Then, by Remarks 2.1 (iv), there exist maximal ideals m1 and m2 of

. Then, by Remarks 2.1 (iv), there exist maximal ideals m1 and m2 of  such that

such that  and

and . Since t > n,

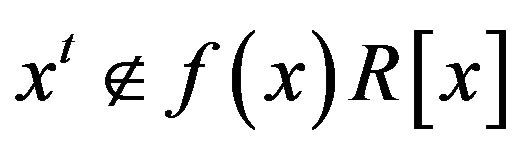

. Since t > n,  and

and . Also, by parts (ii) and (iii) of Remarks 2.1,

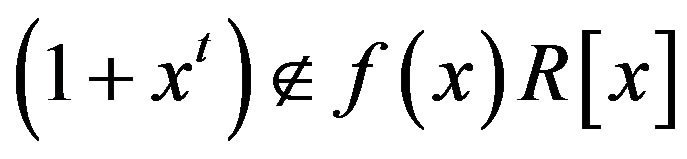

. Also, by parts (ii) and (iii) of Remarks 2.1,  and

and  do not belong to

do not belong to . So,

. So,  and

and

. Thus,

. Thus,  is adjacent to both distinct vertices

is adjacent to both distinct vertices  and

and . Moreover, it is easy to see that

. Moreover, it is easy to see that  is adjacent to

is adjacent to . Therefore we have the cycle

. Therefore we have the cycle

Theorem 2.7 .

.

Proof. Consider the elements  and

and  in

in . So there exist two maximal ideals m1 and m2 in

. So there exist two maximal ideals m1 and m2 in  such that

such that  and

and . Hence the vertex

. Hence the vertex  is adjacent to

is adjacent to . Also, clearly

. Also, clearly  and

and . Now, since the polynomials x and

. Now, since the polynomials x and  do not divide the polynomial

do not divide the polynomial , we have that

, we have that  and

and . Hence

. Hence

is the required cycle.

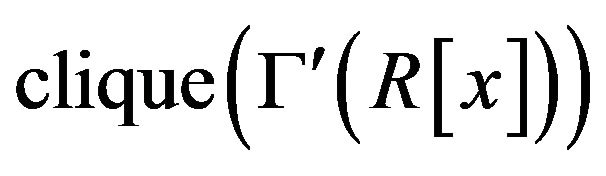

In the next theorem we study the clique number of .

.

Theorem 2.8 In the graph ,

,

is infinity and hence the chromatic number

is infinity and hence the chromatic number  is infinity.

is infinity.

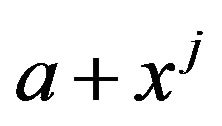

Proof. Let  be a positive integer and consider the subgraph

be a positive integer and consider the subgraph  of

of  with vertex-set

with vertex-set

. Now, for every two distinct polynomials

. Now, for every two distinct polynomials  and

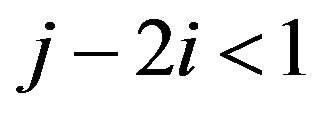

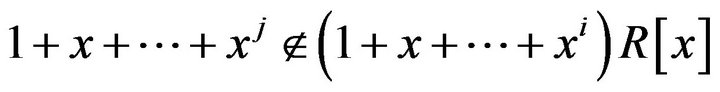

and  with i < j, clearly we have that

with i < j, clearly we have that

Also, since , we have that

, we have that . This means that

. This means that , and so

, and so  does not divide the polynomial

does not divide the polynomial . Thus

. Thus

. Hence,

. Hence,  is a complete subgraph of

is a complete subgraph of  which is isomorphic to

which is isomorphic to

. So

. So  is infinity. This implies that

is infinity. This implies that

is infinity.

is infinity.

Theorem 2.9 The cozero-divisor graph  is not planar.

is not planar.

Proof. In view of the proof of Theorem 2.8, for all positive integers , the cozero-divisor graph

, the cozero-divisor graph  has a complete subgraph isomorphic to

has a complete subgraph isomorphic to . In particular, for

. In particular, for , the graph

, the graph  is a subgraph of

is a subgraph of . So, by Kuratowski’s Theorem (cf. [8, p. 153]),

. So, by Kuratowski’s Theorem (cf. [8, p. 153]),  is not planar.

is not planar.

Recall that a graph on n vertices such that  of the vertices have valency one, all of which are adjacent only to the remaining vertex a, is called a star graph with center a. Also, a refinement of a graph H is a graph G such that the vertex-sets of G and H are the same and every edge in H is an edge in G. Now, we have the following result.

of the vertices have valency one, all of which are adjacent only to the remaining vertex a, is called a star graph with center a. Also, a refinement of a graph H is a graph G such that the vertex-sets of G and H are the same and every edge in H is an edge in G. Now, we have the following result.

Proposition 2.10 If there exists a maximal ideal m of R with , then there is a refinement of a star graph in the structure of

, then there is a refinement of a star graph in the structure of .

.

Proof. Suppose that  is a maximal ideal of R. Then, for every element

is a maximal ideal of R. Then, for every element  with

with , we have that

, we have that . Also

. Also . Hence, a is adjacent to b. Therefore,

. Hence, a is adjacent to b. Therefore,  is a refinement of a star graph with center a. Now, by Remarks 2.1 (v),

is a refinement of a star graph with center a. Now, by Remarks 2.1 (v),  is an induced subgraph of

is an induced subgraph of . So

. So  contains a refinement of a star graph.

contains a refinement of a star graph.

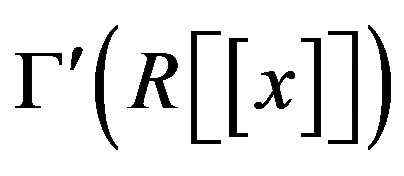

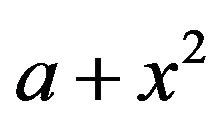

3. Cozero-Divisor Graph of

We begin this section with some elementary remarks about the rings of power series which may be valuable in turn. These facts can be immediately gained from the elementary notes about power series.

• Remarks 3.1

•  is a unit in

is a unit in  if and only if

if and only if  is a unit in R.

is a unit in R.

•  belongs to the Jacobson radical of

belongs to the Jacobson radical of  if and only if

if and only if  belongs to the Jacobson radical of R.

belongs to the Jacobson radical of R.

•  is a local ring if and only if

is a local ring if and only if  is local.

is local.

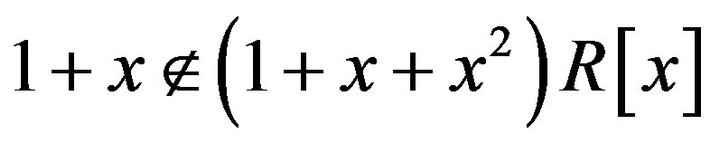

• The cozero-divisor graph  is an induced subgraph of

is an induced subgraph of , but

, but  is not a subgraph of

is not a subgraph of , since 1 + x is a vertex of

, since 1 + x is a vertex of  but it is not in the vertex-set of

but it is not in the vertex-set of .

.

In the following proposition, we study the connectivity and diameter of , whenever R is non-local.

, whenever R is non-local.

Proposition 3.2 Let R be a non-local ring. Then the cozero-divisor graph  is connected and

is connected and

.

.

Proof. Suppose that  is a non-zero element in

is a non-zero element in . By [6, Theorem 2.5], it is enough to show that

. By [6, Theorem 2.5], it is enough to show that  is adjacent to some element in

is adjacent to some element in . In this regard, we have the following two cases:

. In this regard, we have the following two cases:

Case 1. Assume that , for some

, for some  and consider an element b in

and consider an element b in . We will show that

. We will show that  is adjacent to b. Clearly, by Remarks 3.1 (i)(ii),

is adjacent to b. Clearly, by Remarks 3.1 (i)(ii), . Now, assume in contrary that

. Now, assume in contrary that  and look for a contradiction.

and look for a contradiction.

We have that , for some

, for some  in

in . Since, by Remarks 3.1 (ii),

. Since, by Remarks 3.1 (ii),  , we have that

, we have that  which is impossible. Also, if

which is impossible. Also, if

, then

, then , for some non-zero element gi in R, which is impossible. Therefore

, for some non-zero element gi in R, which is impossible. Therefore  and b are adjacent.

and b are adjacent.

Case 2. Suppose that , for all

, for all . First assume that

. First assume that , for some

, for some . Hence, there exist maximal ideals m and

. Hence, there exist maximal ideals m and  such that

such that . By considering an element b in

. By considering an element b in , one can conclude that ai is adjacent to b. Now if

, one can conclude that ai is adjacent to b. Now if , then

, then , for some non-zero element gi in R which is a contradiction because the vertices ai and b are adjacent. On the other hand,

, for some non-zero element gi in R which is a contradiction because the vertices ai and b are adjacent. On the other hand, . Thus the vertices

. Thus the vertices  and b are adjacent.

and b are adjacent.

Now, let , for all

, for all . Choose

. Choose  . Hence

. Hence . We claim that

. We claim that  is adjacent to

is adjacent to , where t is the least non-zero power of

, where t is the least non-zero power of  in the polynomial

in the polynomial . Clearly,

. Clearly, . Now, if

. Now, if

for some

for some  in

in , then

, then

which belongs to  and this is impossible. Hence, we have that

and this is impossible. Hence, we have that  is adjacent to

is adjacent to .

.

Therefore  is connected and also, by considering the above cases, it is routine to check that

is connected and also, by considering the above cases, it is routine to check that .

.

In the next lemma, we investigate the adjacency in  in the case that R is a local ring.

in the case that R is a local ring.

Lemma 3.3 Assume that R is a local ring with maximal ideal m. Let  be a non-zero element in

be a non-zero element in . Then we have the following statements:

. Then we have the following statements:

• if , then

, then  is adjacent to

is adjacent to ;

;

• if  and

and , for some

, for some , then

, then  is adjacent to all non-zero elements of

is adjacent to all non-zero elements of ; and• if

; and• if  and

and , for all

, for all , then

, then  is adjacent to

is adjacent to , where

, where  is the least non-zero power of

is the least non-zero power of  in

in .

.

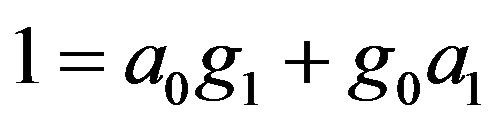

Proof. 1) Assume on the contrary that , where

, where . Then

. Then  and

and  . Since a0 and g0 belong to m, we have that

. Since a0 and g0 belong to m, we have that  which is a contradiction. Also we have that

which is a contradiction. Also we have that . Thus

. Thus  is adjacent to x.

is adjacent to x.

2) Let b be a non-zero element in m. Then if , we conclude that

, we conclude that  which is impossible. So

which is impossible. So . Now, since

. Now, since

. Therefore,

. Therefore,  is adjacent to

is adjacent to .

.

3) Clearly, since  is the least non-zero power of

is the least non-zero power of  in

in ,

, . Moreover, if

. Moreover, if  , for some

, for some  in

in , then

, then

This means that  which is impossible. Hence

which is impossible. Hence . So

. So  is adjacent to

is adjacent to .

.

The following result, which is one of our main results in this section, states that  is connected and the diameter of

is connected and the diameter of  is not exceeding four.

is not exceeding four.

Theorem 3.4 The cozero-divisor graph

is always connected and also .

.

Proof. Owing to Proposition 3.2, the result holds in the case that R is non-local. Assume that R is a local ring with maximal ideal m. In view of part (iii) of Remarks 3.1,  is also a local ring. Now, let

is also a local ring. Now, let  and

and  be two non-zero elements in

be two non-zero elements in  that are not adjacent. We have the following cases for consideration:

that are not adjacent. We have the following cases for consideration:

Case 1.  and

and . Then by Lemma 3.3 (i), we have that

. Then by Lemma 3.3 (i), we have that .

.

Case 2. . If

. If , for some i, j, then by part (ii) of Lemma 3.3,

, for some i, j, then by part (ii) of Lemma 3.3,  , for all non-zero elements

, for all non-zero elements  in

in .

.

Also, if , for all

, for all , and

, and  are the least non-zero powers of x in

are the least non-zero powers of x in  and

and , respectively, with

, respectively, with , then by Lemma 3.3 (iii), one can easily check that

, then by Lemma 3.3 (iii), one can easily check that .

.

Finally, we may assume that for some positive integer i,  and

and , for all j. Thus, by parts (ii) and (iii) of Lemma 3.3, we have the path

, for all j. Thus, by parts (ii) and (iii) of Lemma 3.3, we have the path  , where c is a non-zero element in

, where c is a non-zero element in  and

and  is the least non-zero power of x in

is the least non-zero power of x in .

.

Case 3. Without loss of generality, we may assume that  and

and . So, if

. So, if , for some j, then in view of parts (i) and (ii) of Lemma 3.3, we have the path

, for some j, then in view of parts (i) and (ii) of Lemma 3.3, we have the path , where

, where  is a non-zero element in m.

is a non-zero element in m.

Moreover, if , for all j, then by Lemma 3.3, we have

, for all j, then by Lemma 3.3, we have , where

, where  is a non-zero element in m and t is the least non-zero power of

is a non-zero element in m and t is the least non-zero power of  in

in .

.

Therefore, the cozero-divisor graph  is connected and in view of the above cases, one can easily check that

is connected and in view of the above cases, one can easily check that .

.

The following lemma is needed in the sequel.

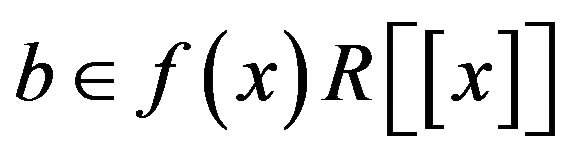

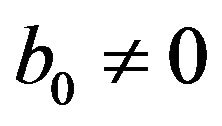

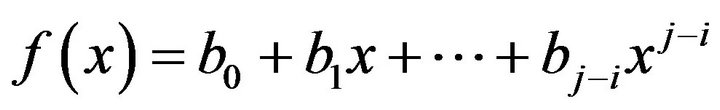

Lemma 3.5 Let  and let i and j be positive integers such that

and let i and j be positive integers such that . Then the vertices

. Then the vertices  and

and  are adjacent in

are adjacent in .

.

Proof. Suppose to the contrary that  , where

, where  is a non-zero polynomial in

is a non-zero polynomial in . So, we have

. So, we have  and b0 = 0. Thus a = 0 which is a contradiction. Hence

and b0 = 0. Thus a = 0 which is a contradiction. Hence . Also, clearly

. Also, clearly . So the vertices

. So the vertices  and

and  are adjacent in the cozero-divisor graph

are adjacent in the cozero-divisor graph .

.

In the next theorem, we show that .

.

Theorem 3.6 The cozero-divisor graph  has girth three.

has girth three.

Proof. Let . Consider the elements x,

. Consider the elements x,  and

and  in

in . Clearly,

. Clearly,

and

and . Also, since

. Also, since

,

,  and

and  don’t belong to

don’t belong to . Hence, we have the following path

. Hence, we have the following path

Now, in view of Lemma 3.5, one can conclude that  and

and  are adjacent. Therefore, we have the cycle

are adjacent. Therefore, we have the cycle . Hence,

. Hence,

.

.

In the next theorem, we compute the clique number of .

.

Theorem 3.7 In the graph ,

,

is infinity and hence

is infinity and hence  is also infinity.

is also infinity.

Proof. For every positive integer , it is enough to construct a complete subgraph of

, it is enough to construct a complete subgraph of  with

with  vertices. To this end, let

vertices. To this end, let  be an arbitrary positive integer and

be an arbitrary positive integer and . Then, by Lemma 3.5, it is easy to see that the subgraph with vertex-set

. Then, by Lemma 3.5, it is easy to see that the subgraph with vertex-set

is a complete subgraph of

is a complete subgraph of

which is isomorphic to

which is isomorphic to . So

. So

is infinity and this implies that

is infinity and this implies that  is infinity.

is infinity.

We end this section with the following theorem.

Theorem 3.8 The cozero-divisor graph  is not planar.

is not planar.

Proof. In view of the proof of Theorem 3.7,  is a subgraph of

is a subgraph of . Thus, by Kuratowski’s Theorem,

. Thus, by Kuratowski’s Theorem,  is not planar.

is not planar.

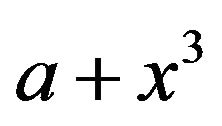

4. Cozero-Divisor Graph of

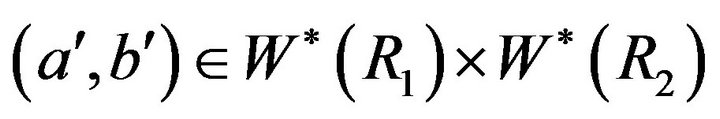

Throughout this section, R1 and R2 are two commutative rings with non-zero identities. We will study the cozerodivisor graph of the direct product of R1 and R2. Note that an element  belongs to

belongs to  if and only if

if and only if  or

or . We begin this section with the following lemma.

. We begin this section with the following lemma.

Lemma 4.1 Suppose that  is a direct product of finite commutative rings. If

is a direct product of finite commutative rings. If  is adjacent to

is adjacent to  in

in , for some

, for some , then every element in R with i-th component

, then every element in R with i-th component  is adjacent to all elements in R with i-th component

is adjacent to all elements in R with i-th component .

.

Proof. Suppose that  is adjacent to

is adjacent to  in

in  and assume on the contrary that the vertices

and assume on the contrary that the vertices  and

and  are not adjacent in

are not adjacent in . Without loss of generality, suppose that

. Without loss of generality, suppose that

. Thus

. Thus

, for some non-zero element

, for some non-zero element . Therefore

. Therefore  and hence

and hence  is not adjacent to

is not adjacent to , which is a contradiction.

, which is a contradiction.

The following corollary follows immediately from Lemma 4.1.

Corollary 4.2 Suppose that ,

,

such that they are not adjacent in

such that they are not adjacent in . Then a is not adjacent to

. Then a is not adjacent to  in

in  and b is not adjacent to

and b is not adjacent to  in

in .

.

In the next lemma, we establish some relations between the adjacency in the graph  and adjacency in both graphs

and adjacency in both graphs  and

and .

.

• Lemma 4.3

• Let  and

and . Then

. Then  is adjacent to

is adjacent to  in

in  if and only if b is adjacent to

if and only if b is adjacent to  in

in .

.

• Let  and

and . Then

. Then  is adjacent to

is adjacent to  in

in  if and only if

if and only if  is adjacent to

is adjacent to  in

in .

.

Proof. 1) Suppose that  is adjacent to

is adjacent to . Note that if at least one of the elements

. Note that if at least one of the elements  or

or  is zero or unit, then

is zero or unit, then  is not adjacent to

is not adjacent to  in

in . Thus we can suppose that

. Thus we can suppose that . Now, if

. Now, if  is not adjacent to

is not adjacent to , then

, then  or

or . So without loss of generality, we may assume that

. So without loss of generality, we may assume that  for some non-zero element

for some non-zero element . Hence

. Hence . This means that

. This means that  and

and  are not adjacent in

are not adjacent in  which is impossible. Therefore

which is impossible. Therefore  and

and  are adjacent in

are adjacent in . Conversely, if

. Conversely, if  is adjacent to

is adjacent to , then by Lemma 4.1, we have that

, then by Lemma 4.1, we have that  is adjacent to

is adjacent to .

.

2) The proof is similar to part 1).

The following propositions follow directly from Lemma 4.3.

Proposition 4.4 Assume that either  or

or  is not planar. Then

is not planar. Then  is not planar.

is not planar.

Proof. Without loss of generality, suppose that  is not planar. So, by Kuratowski’s Theorem (cf. [8, p. 153]), it contains a subdivision of

is not planar. So, by Kuratowski’s Theorem (cf. [8, p. 153]), it contains a subdivision of  or

or . Now, by Lemma 4.3 (ii), one can conclude that

. Now, by Lemma 4.3 (ii), one can conclude that  is not planar.

is not planar.

Proposition 4.5 In , we have the following inequalities:

, we have the following inequalities:

;

;

•  .

.

Remark 4.6 Suppose that  and

and . Then

. Then  is adjacent to

is adjacent to .

.

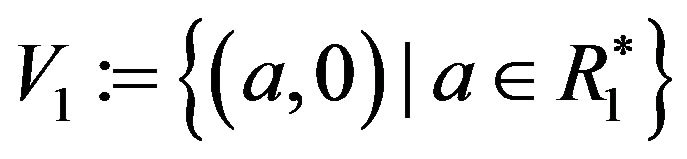

In the following theorem, we invoke the previous lemmas to show that  is a complete bipartite graph whenever

is a complete bipartite graph whenever  and

and  are fields.

are fields.

Theorem 4.7 Assume that  and

and  are fields. Then

are fields. Then  is a complete bipartite graph.

is a complete bipartite graph.

Proof. Put  and

and

. Clearly

. Clearly . By Remark 4.6, every element in V1 is adjacent to all elements of V2 and vice versa. Also, it is easy to see that there is no adjacency between vertices in V1 (or V2). So

. By Remark 4.6, every element in V1 is adjacent to all elements of V2 and vice versa. Also, it is easy to see that there is no adjacency between vertices in V1 (or V2). So  is a complete bipartite graph.

is a complete bipartite graph.

Corollary 4.8 Let  be an arbitrary field. Then

be an arbitrary field. Then  and

and  are star graphs.

are star graphs.

Remark 4.9 It is easy to see that  is adjacent to

is adjacent to  in

in , for any

, for any ,

,  and

and . Similarly,

. Similarly,  is adjacent to

is adjacent to

, for any

, for any ,

,  and

and  .

.

The following theorem is one of our main results in this section.

Theorem 4.10 The cozero-divisor graph  is connected and

is connected and .

.

Proof. Suppose that  and

and  are arbitrary elements in

are arbitrary elements in . We have the following cases for consideration:

. We have the following cases for consideration:

Case 1. . If

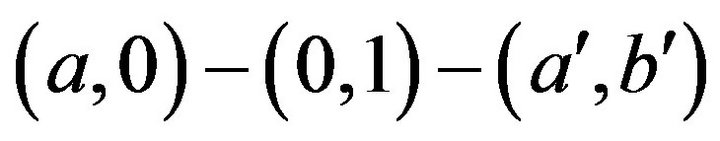

. If , then consider the path

, then consider the path . If

. If  and

and , then, by Remark 4.9, we have that

, then, by Remark 4.9, we have that . Now, suppose that

. Now, suppose that  and

and . Then, in view of Remarks 4.6 and 4.9, one can obtain the path

. Then, in view of Remarks 4.6 and 4.9, one can obtain the path  in

in . The similar result holds in the case that

. The similar result holds in the case that  and

and .

.

Case 2.  and

and . If

. If , then, by Remark 4.9, whenever

, then, by Remark 4.9, whenever , we have that

, we have that

. Otherwise,

. Otherwise, . Since

. Since  and

and , we have

, we have . Now, if

. Now, if

, then

, then . But

. But  and this implies that

and this implies that  which is not true. Hence

which is not true. Hence . Also, since

. Also, since , it is easy to see that

, it is easy to see that . Therefore, we have the path

. Therefore, we have the path . Also, if

. Also, if , then by Remarks 4.6 and 4.9, we can consider the path

, then by Remarks 4.6 and 4.9, we can consider the path . The similar result holds if

. The similar result holds if

and

and .

.

Case 3. . Then we have that

. Then we have that  , and we can apply Case 1 on the second component of ordered pairs.

, and we can apply Case 1 on the second component of ordered pairs.

Now, in view of the above cases, it is easy to see that .

.

In the next proposition, we provide a characterization of the complete cozero-divisor graph .

.

Proposition 4.11 The graph  is complete if and only if

is complete if and only if  is isomorphic to

is isomorphic to .

.

Proof. If , then

, then  is not adjacent to

is not adjacent to , for some

, for some . Similarly, if

. Similarly, if , then

, then  is not complete. So, if

is not complete. So, if  is complete, then

is complete, then . Also, clearly the graph

. Also, clearly the graph  is complete.

is complete.

Corollary 4.12 If , then

, then  or 3.

or 3.

In the following theorem, we study the girth of  . Note that we consider

. Note that we consider  to be totally disconnected.

to be totally disconnected.

• Theorem 4.13

• If at least one of the cozero-divisor graph  or

or  is not totally disconnected, then

is not totally disconnected, then  .

.

• If  and

and , then

, then .

.

• If  and R2 is a field, then

and R2 is a field, then .

.

• If  and R2 is not a field, then

and R2 is not a field, then  or

or .

.

Proof. 1) Without loss of generality, suppose that  such that a is adjacent to b. Now, by Lemma 4.3 (i) and Remark 4.9, we have the cycle

such that a is adjacent to b. Now, by Lemma 4.3 (i) and Remark 4.9, we have the cycle  in

in .

.

2) Let  and

and  such that a and b are not identity. Now, consider the cycle

such that a and b are not identity. Now, consider the cycle

in

in .

.

3) By Corollary 4.8,  is a star graph and so

is a star graph and so .

.

4) First, assume that . Let

. Let  and

and . Now, by Remarks 4.6 and 4.9, we have the cycle

. Now, by Remarks 4.6 and 4.9, we have the cycle  in

in . In the case that

. In the case that , if

, if  is not totally disconnected, then by part 1),

is not totally disconnected, then by part 1),  . So, assume that there is no adjacency in

. So, assume that there is no adjacency in . In this situation, we first show that

. In this situation, we first show that  is a bipartite graph. To this end, set

is a bipartite graph. To this end, set

and

and . Clearly,

. Clearly,

. Also, by Lemma 4.3, no two vertices in

. Also, by Lemma 4.3, no two vertices in  (or

(or ) are adjacent. So

) are adjacent. So  is a bipartite graph, and thus

is a bipartite graph, and thus  or

or . Now, by Remark 4.9,

. Now, by Remark 4.9,  is adjacent to all vertices

is adjacent to all vertices  in

in , where

, where , and also

, and also  is adjacent to all vertices

is adjacent to all vertices  in

in , where

, where . Hence, if there exist an element

. Hence, if there exist an element  and

and  such that

such that  is adjacent to

is adjacent to  in

in , then

, then . Otherwise, the girth of the cozero-divisor graph

. Otherwise, the girth of the cozero-divisor graph  is infinity.

is infinity.

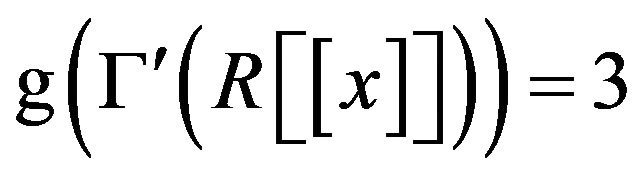

The following example presents a ring  with

with  which satisfies parts 1) and 4) of Theorem 4.13. This shows that all cases in the proof of the last part of Theorem 4.13, can occur.

which satisfies parts 1) and 4) of Theorem 4.13. This shows that all cases in the proof of the last part of Theorem 4.13, can occur.

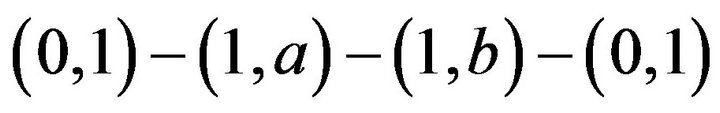

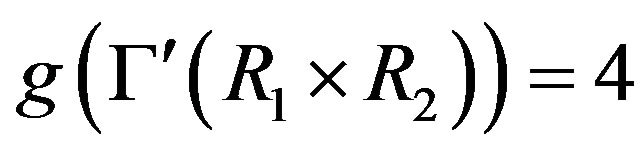

Example 4.14 Let  and

and . Then

. Then  and by Proposition 4.11,

and by Proposition 4.11,  is complete. Hence, by Theorem 4.13 (i), we have that

is complete. Hence, by Theorem 4.13 (i), we have that .

.

5. Acknowledgements

The authors are deeply grateful to the referee for careful reading of the manuscript and helpful suggestions.

NOTES