A Pilot Experience in the training of healthcare professionals to face the childhood obesity epidemic through family therapeutic education ()

1. INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a major public health issue: a real epidemic [1]. Currently, in Italy more than 4 persons out of 10 are overweight (42%) [2]. The incidence is also high in children [3-5], and it has tripled in the last 30 years [6]; moreover, the risk of persistence from childhood through adulthood is very high [7]. Worldwide costs are high [8-10]: obesity is responsible for an increase in cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes in adulthood [11]. Therefore, experts advise to begin management early in life [12].

Unfortunately, proven effective therapies are still weak and many published studies are conducted only on small series of patients, with short follow-up periods and disappointing results [13]. Therefore, while primary care pediatricians (PCPs) are not very motivated [14], researchers tend to develop long, complicated, and laborious therapeutic approaches for PCPs and even for specialists such as endocrinologist pediatricians (EPs) and dietitians (D) [15-17]. Finally, for most families, time and cost along with limited faith in therapy is the most important obstacle to lifestyle changes [18,19].

The large number of overweight children has forced National Health Care Systems worldwide to involve PCPs in their management. In Italy, the National Health Plan [20] includes actions to prevent obesity in young women and children, and the Italian Society for Pediatrics reached a Consensus in 2005 [21]. Today numerous studies demonstrate the feasibility and efficacy of obesity treatment, outside specialist settings, among primary care [22-27]. Nevertheless, PCPs usually limit themselves to mere dietary advice and do not believe in the efficacy of treatment nor do they feel prepared to approach it.

Many barriers are encountered when treating obesity; therefore few children are actually evaluated and treated with adequate approaches [14,24,28-30]. The position of professionals is one of the barriers, both in specialist and primary care settings, that some Authors call “Obesity Resistance Syndrome” [31]. Many attempts to train professionals have been described [32]; the seeking to motivate professionals by providing training, involvement, objectives and appropriate tools, is still without scientific evidence to support them [33].

In 2000 the authors, with the objective of creating a standardized therapeutic procedure for pediatricians, developed and tested a Family Therapeutic Education (FTE) program for childhood obesity [34,35] at the Pediatric Department of Ferrara, which is effective and positively accepted by families. The FTE program was called “The Game of Pearls and Dolphins”, a name proposed by the children, in order to divest the terms “obesity” and “diet” of their negative meanings [36], replacing them with images of beauty and dynamism.

The program includes only two medical and pedagogical examinations and one group educational session with families, followed by 1 - 2 follow-up medical examinations per year, in order to render the program feasible in public health facilities.

The first consultation includes a complete physical examination for obesity and some questions on the family history of weight-related problems and motivation towards change.

The group meeting for children (over 11 years old) and parents encourages learning and reduces sense of guilt and unrealistic goals. The last consultation clarifies individual risks and provides families with positive reinforcement on initial behavioral and clinical changes.

A retrospective evaluation of the program, carried out with the advice and support of a therapeutic patient education team from Padua University Hospital, now with a larger number of subjects, has observed satisfactory results at a 3 years follow-up [35].

It thus seems that even short interventions, when conducted with skillfulness and enthusiasm, provide positive and lasting results at lower costs. Following the positive results of this experience, the authors propose to transfer and test their program in other Italian centers by training pediatricians, above all PCPs and dietitians, and creating a network among them.

The aim of this work is to assess whether a training program for FTE, structured in a timely and sustainable manner for all professionals involved, can reduce obstacles towards appropriate care of obese children and their families, overcoming the attitude of denial and waiting. Therefore, we are presenting and discussing the first results of a two-year pilot professional training project, designed to provide specific educational skills to the involved healthcare personnel.

2. METHODS

2.1. Family Therapeutic Education

The use of Therapeutic Patient Education in the treatment of certain illnesses, like childhood obesity, is still at its beginning and requires further adjustment, although recent studies confirm its efficacy [37,38].

In particular the FTE adopted the following principles and methods:

1) A family approach: the program is reserved for the family members of children aged under 11 years, while adolescents over 11 years are involved with their families according to their level of maturity [16,39-41];

2) A therapeutic approach including the affective-relational involvement of professionals [42];

3) The modeling proposed by professionals to the family and, in turn, by the family to children about sedentary conduct, physical activity and eating behavior [43];

4) Procedures and tools to develop and support behavioral change “behavioural therapy”: motivational counseling to produce self-awareness and encourage self-management; therapeutic contract to share agreement of therapeutic objectives, goal setting to support the acceptance of realistic if transitory goals, positive reinforcement of previous good choices and of every positive small result achieved, with the aim of encouraging selfesteem and self-efficacy and evaluation instruments [44];

5) The recovery of the value of previous treatments: narrative therapy [45];

6) The reduction of a sense of guilt;

While Behavioral Therapy for lifestyle changes has demonstrated efficacy in reducing weight [13,46] it is not yet clear which are the most effective and/or necessary tools to achieve the expected weight loss. Of the single tools used, only the family approach has evidence of efficacy [13,15,46]; other tools have been evaluated in single studies. Motivational interviewing, introduced in therapeutic guidelines and recommendations in many countries, has not proven to be effective [18,47-51]. The reduction of a sense of guilt is proposed by the authors of this study, but poorly sustained by others. It goes beyond the indications of non-judgmental listening shared in the literature [52,53]. Although recognizing that sense of guilt can strongly motivate change in education therapy for obesity in adults [54], we propose its active reduction, considering that this disease in childhood is already burdened by an excessive sense of guilt which paralyzes change in families.

FTE is aimed at changing mental representations, emotional attitudes and behaviour of children and families towards food and physical activity, without worsening quality of life, by encouraging self-management and empowerment of families [55]. Despite the lack of conclusive evidence, the American Academy of Paediatrics has included the above mentioned principles and methods in its 2007 recommendations [18].

In particular, the original FTE study involved 254 overweight and obese children (BMI ≥ 85˚ and ≥95˚ percentile) [35] aged 10.4 ± 3 years, without relevant psychiatric comorbidities, 127 treated with FTE and 127 with diet therapy. After at least 1 year (mean time 2.8 ± 1.3 years), the BMI z-score after FTE, calculated on CDC 2000 curves [56], was reduced by 0.43 ± 0.5, while it remained unchanged in the diet therapy group, with a great reduction of severe forms (BMI > 99˚ percentile). The assessment questionnaires administered to the FTE group after at least one year, showed an improvement in both eating (87%) and physical activity behavior (72%) and a better quality of life (over 90%).

The FTE has been entirely managed by one pediatrician of the Ferrara University Hospital, competent in obesity, eating disorders and education of patients. Other healthcare professionals (dieticians and psychologists) have allowed extension of the pediatrician’s competencies and treatment of more severe and complicated cases.

2.2. The Pilot Training Project

In 2007, our team prepared a training project to teach our FTE program and involve other pediatricians, dieticians and nutritionists, who were dissatisfied and interested in improving both the quality and quantity of their treatment of obesity. It is aimed at one professional at a time, a maximum of two if they are part of the same team.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ferrara on 26th June 2008, in accordance with applicable legislations.

It consisted of an e-learning project on main topics about childhood obesity and of a short field training session of two days in our outpatient facilities with families, to create an integrated learning experience [57]. A second phase of the field training (two days) took place two months later. At that time the professionals, having acquired their own personal experiences with their patients, could discuss their problems or unanswered questions with trainers.

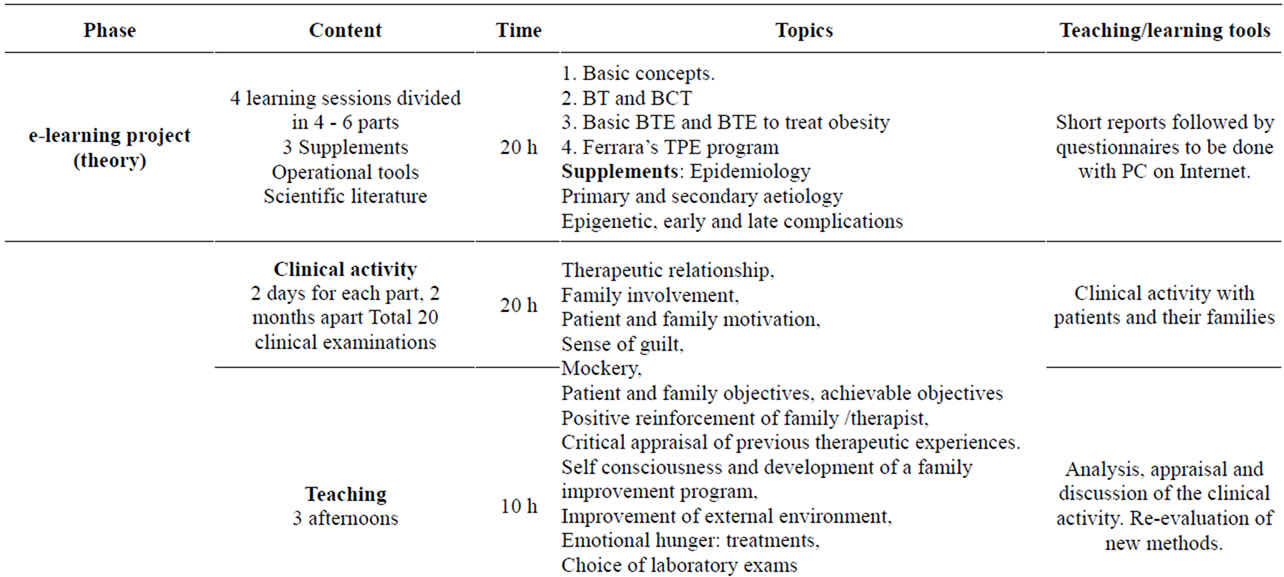

This mixed resident/on-line training of healthcare professionals allows us to combine the advantages of easy internet access, managed according to personal times and spaces, with a direct relationship with the tutor and families. E-Learning projects are as effective as traditional training in improving knowledge and initiating changes in clinical practice at lower costs. The field training has an important impact on training: theoretical concepts are revisited and directly illustrated through clinical cases, and it is possible to witness the results of the project on BMI and quality of life. The characteristics of the training project are summarized in Table 1.

One of the objectives of the project is to promote in the learners a sense of self-efficacy [32,58,59], i.e., the belief of possessing the capability and competencies to successfully carry out a certain task. It is a fundamental milestone for professional motivation. This objective is pursued by providing information and instruments, demonstrating results, and especially by supporting doctors in the difficult task of treating this disease. Practically speaking, bringing a doctor to believe in his/her own capabilities and competencies in treating obesity, unconsciously increases his/her involvement and improves results. Empowered doctors empower patients and vice versa [60].

We hypothesize that this project will have the following effects:

1) improve experience and knowledge of PCP, EP and D;

2) increase their perceived efficiency and efficacy, modifying attitudes and perceptions;

3) create teams, if possible, for the integrated and interdisciplinary management of patients with severe or complicated obesity.

2.3. Participants

The first edition of the training project began in February 2008. The project was proposed to physicians and dietitians who treat childhood obesity, and who requested to see and develop our innovative treatments after learning about them through presentations at pediatric endocrinologic conferences. After publication of our FTE in a widely-read Italian journal other professionals requested training.

Table 1. Contents and timetable of the professional training to therapeutic patient education.

Participants were informed about the study and signed a written consent for the management of data. Planned enrolment was 10 participants in 2008 and 5 in 2009. Nine people (5 pediatricians, 1 nutritionist and 3 dietitians) completed the training project in 2008, and 5 completed it in 2009.

2.4. Tools

Members of the Padua and Ferrara teams represent the Scientific Committee of the project, whose task was to create and coordinate the training course, evaluate its development, implementation, necessary changes and final impact on treatment. This committee includes experts in Obesity, Therapeutic Patient Education, Continuing Medical Education and on-line training.

The course also includes didactic material for physicians and families. Physicians had access to all resources needed for group seminars and instructional meetings with families. Communication over the internet gave immediate feedback from and to the scientific committee (discussion forum).

To evaluate the efficacy of the project on the growth of knowledge, motivation and self-efficacy, and improvement of clinical practice, both self-completed multiple-choice and open answer tutor-administered questionnaires were used, and data collected. Questionnaires regarded obesity management, expectations and experiences before and after the course.

We used the following tools in order to evaluate the results of the course:

1) Twenty short questionnaires (90 items) associated with the e-learning project; rather than to evaluate, they have been conceived to motivate and improve learning; in fact, they allow participants to check their results and, if negative, can be repeated.

2) One self-administered questionnaire of 18 questions administered two times before and after the training project on motivational interviewing, stages of change for behavioral therapy [44], induction of motivation, behavioral techniques and practical use of therapeutic narration. This questionnaire investigates the advantages of doctors’, family’s and child’s motivation in treating obesity, the history of child’s and parents’ weight problems, the previous attempts of self-managed or professionally managed treatment and evaluate small or very small results, react to family abandonment or requests of excess or quick weight loss.

3) A concluding interview immediately after completing the project, investigates the increase in partecipants’ motivation, competence, efficacy, quality of communication in treating obesity, change from new versus traditional approach.

4) A questionnaire sent to participants after 6 - 12 months, and for the nine 2008 course participants at 24 months after completion of the training, on the persistence of results of the FTE program, that is if participants are still motivated and able to develop good communication with families.

5) A 10-point Likert questionnaire with 13 items completed 6 - 12 months after the end of training: every item can receive a score from 0 to 10 (0 = not at all and 10 = maximum). This questionnaire also investigates the longterm results of training, that is whether it teaches new treatment strategies, provides increased competence in diagnosis and treatment, motivation in treating, quality of professional communication, change of approach and whether it is a valid teaching method to develop awareness and new daily working methods with important professional results, improves the acceptance of the therapy for families, helps families change, decreases the time of visits, reduces aggressiveness and sense of guilt.

All the questionnaires and the interviews were administered by the same operator. Details on the methods are available by contacting the project’s corresponding author.

2.5. Data Analysis

Data from different sources are grouped according to evaluable parameters. Quantitative data are evaluated through appropriate descriptive statistics, i.e. means with standard deviations for normally distributed variables. Qualitative data will be analyzed using codification of comments and information.

2.6. Clinical Investigation

To evaluate the efficacy of the project in clinical practice and support the participants training, we asked those who chose to change their therapeutic approach based on what they learned during the training course to send us anthropometric data on the children in their care who are treated with these methods along with their impressions of the changes.

2.7. Data Collection

Six participants (3 pediatricians, and 3 dietitians) of 9 of our 2008 training project group, who reformulated their therapeutic approach, collected anthropometric data of a total of 264 children. They are two PCPs [one from the Centro Studi Federazione Italiana Medici Pediatri in Naples and one from a PCP in Pavullo (Modena)], one EP [Centro di prevenzione diagnosi e cura dell’obesità in età evolutiva in Gallipoli (Lecce)], and three Ds [one at the Centro di Medicina generale e Pediatria of Reggio Emilia, one at the U.O. Diabetologia, Nutrizione Clinica e Obesità Pediatrica of the University of Verona and one non-affiliated dietitian in Urbana (Padova)].

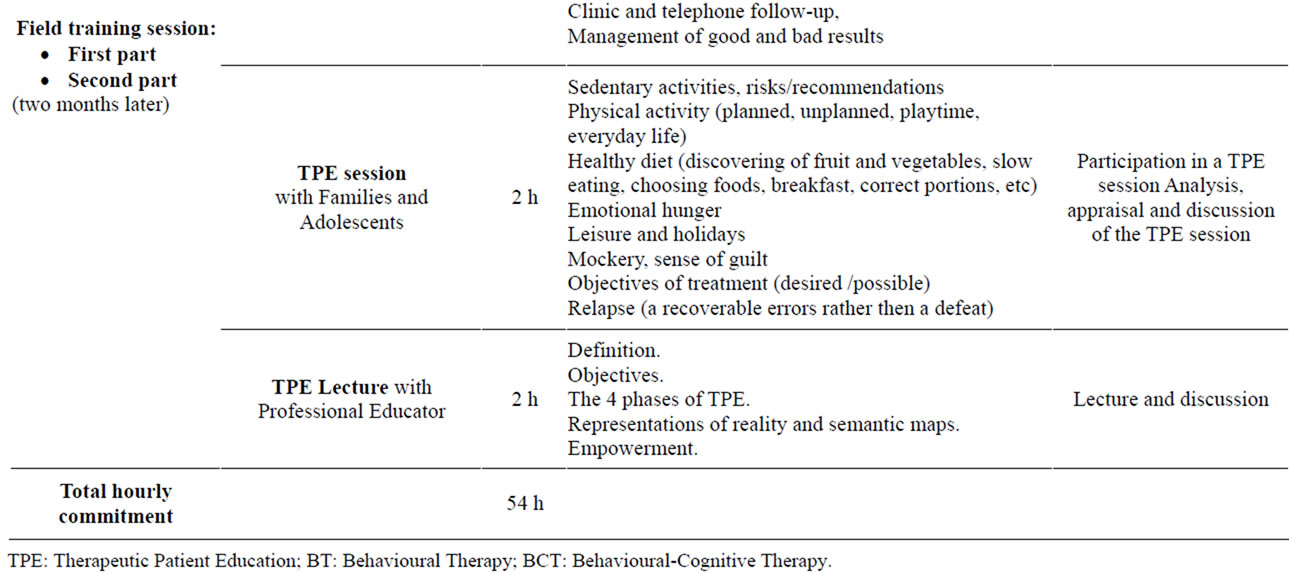

Children aged 8.9 ± 4 years (48% males), with an initial BMI z-score 1.93 ± 0.5, attending the FTE program were reevaluated after a follow-up of at least 6 months, to detect changes in BMI z-scores (Table 2). Data were

Table 2. Characteristics of patients treated by participants using FTE methods and changes in their BMI z-score according to the CDC criteria [45] at follow-up.

personally collected by the 6 participants, sent telematically, and evaluated by the study leader and the statistician of the FTE program published [34,35].

2.8. Patient Measurements

Body height, expressed in 0.1 cm intervals, was measured by a stadiometer, while body weight, expressed in 0.1 kg intervals, was determined by a medical balance beam scale. Height and weight were used to calculate BMI: kg/m2. BMI expressed as a standard deviation score (BMI z-score), was calculated according to CDC 2000 [56], by usual least mean square method [61]. BMI z-scores were recorded at baseline and after the followup period, to compare values and assess their changes [62].

2.9. Data Analysis

The anthropometric data of children, used to detect changes in BMI z-scores, were analyzed using SPSS v.8.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago IL, USA), and Statgraphics v.4.0 (STSS, Inc. Rockville, MD, USA).

3. RESULTS

Questionnaires and interviews proposed to the 14 participants completing the 2008-2009 training projects provided the following results:

1) The e-learning questionnaires: 100% correct answers.

2) The questionnaire A: all the participants were very motivated and culturally prepared; many of them had been working with obese children for years (average 6.5 ± 6 years). The percentage of correct answers increased from 75% (pre-test) to 97% (post-test). Initially, 10 out of 14 affirmed that they were dissatisfied with their work. In the final questionnaire everyone declared an increase in motivation, competency and confidence in their practice (12 out of 14 defined the difference as “remarkable”).

3) The concluding interview revealed increased motivation, competency (13 participants out of 14 interviewed agreed with this statement), ability to communicate (for 12 out of 14) and efficacy (for 8 out of 14). All participants agreed that the program is feasible, advantageous and effective, although 50% (7 out of 14) admit that changing will be difficult. The innovations that most struck the participants were the empowerment (12 out of 14), working with families (11 out of 14), the relief from feelings of guilt, the management of conflict, narrative therapy, the systematic approach, the specific approach for adolescents, the educative group meeting, the management of the entire course by a single operator with multidisciplinary competences. Nine out of 14 declared themselves available for a multicenter study (three of them are too young and do not have their own ambulatory). The key points of their interviews are summarized in Table 3.

4) The questionnaire sent after 6 - 24 months on persistence of results, confirms that they all still find our FTE program innovative and describes with enthusiasm their experience with it. All the participants found it feasible and without difficulties, feel more motivated, competent and able to develop good communication with families; only 2 do not find the program more effective, 8 confirmed their availability for a multicenter study and 6 sent data from their patients. All report having made some changes and personal adjustments in their lifestyle that proved advantageous for themselves, the children and their families; 6 out of the 2008 group reported initial positive results on children’s weight.

All the participants suggest it is feasible and advantageous to train more health professionals and develop a continuous learning project; they suggest improving the program by adding 2 or more group meetings with families and adolescents in the program and giving more space and attention to the search for barriers to change.

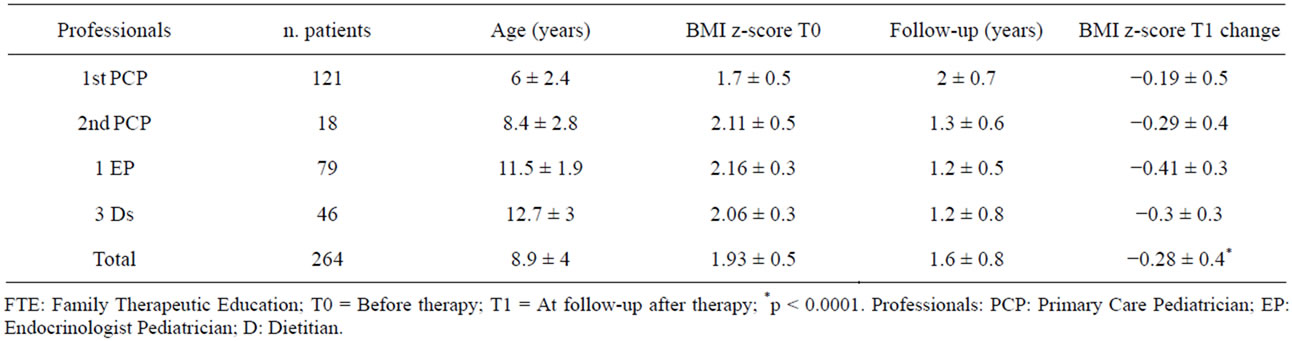

The 10-point Likert questionnaires suggest the FTE is innovative (Item 1) with an average score (AS) of 8.2; while their motivation, competency and communication improvements (Items 2-4) obtained a mean AS of 8.3; the teaching techniques adopted (Items 6-8) obtained a mean AS of 8.8. Even the evaluation of their personal lifestyle change, therapeutic approach and family behaviors (Items 5, 9-13) showed an improvement but with a lesser degree of accordance in scores. 9 professionals affirmed that 6 - 12 months did not seem enough time to evaluate actual changes in professionals and families’ behaviors (mean AS 7.4) (Figure 1).

Clinical Investigation Results

In the children treated by the six 2008 participants a BMI z-score reduction of 0.28 ± 0.4 was registered after 1.6 ± 0.8 years, (p < 0.0001). The number of children with severe obesity in treatment went from 51 to 22: a reduction of 57%. A total of 220 children (83%) registered an average BMI z-score reduction of 0.4 ± 0.4 (Table 2).

4. LIMITATIONS

Our study has several limits:

1) The small number of participants.

2) The difficulty in assessing the practical outcomes of the training program: we used questionnaires or interviews, which give personal subjective evaluations, difficult to analyze statistically and influenced by the relationship created during training.

3) The time necessary for each participant to training.

Table 3. Observations of participants after the course.

4) The clinical investigation results are relative to only 6 participants out of 9 (2 were still in professional training, 1 changed work place and lost access to previous data). Furthermore, even if results, according to BMI z-score change, seem to show a weight loss (Table 2), they are questionable. There is no control group and the follow up period is short for an educational program aimed at fostering awareness and motivation to behavioral change, capable of producing a real transformation in lifestyle and health status.

5. DISCUSSION

According to the results of evaluation questionnaires, the feedback of the attendees, especially PCPs, is positive; after completing the training, they became more confident with the therapeutic education, involved their collaborators, suggested trying the procedure to other colleagues and sought institutional support to create a professional network in their area. The statistic analysis of available anthropometric data reported in several medical conventions reinforced the consciousness and motivation of our attendees also increasing their self-esteem and sense of efficacy. The reduction in BMIz scores of 0.28 after treatment is considered significant of fat mass reduction in childhood [63]. This also contributed to increased credibility and prestige with their teams. Finally, there is no doubt that the course promoted an atmosphere of confidence, self-efficacy and enthusiasm among participants that is attracting the increasing interest of other professionals.

Our training project has very affordable costs for the instructors [33]. The e-Learning project, in fact, has a

Figure 1. Average score of 10-point Likert 13-item questionnaire completed 6 - 12 months after the training program about their motivation, competency, communication teaching techniques adopted, personal lifestyle change, therapeutic approach and patients’ family behaviors.

minimal start-up cost and it only needs periodic updating every 1 - 2 years; it does not require participants to travel from their workplace and can easily be used at times and in ways that are most convenient for participants who view material on their computer, and can print all the necessary material for the therapeutic program.; additionally, instructors are able to continue their professional outpatient activities with the trainees.

The program takes about 14 hours of the instructor’s time for each trainee, but if efforts are properly coordinated 2 trainees might be trained more cost-effectively at the same time and with little extra effort. Even support for the trainees as they attempt to put the project into practice was conducted on line, therefore consuming little in terms of resources. The project also broadened views regarding the possibilities of therapy for obesity of all those involved both trainees and instructors, leading to deep thought and more adequate therapeutic behavior. It has also increased the sense of self-efficacy of the members of the organizing-scientific team by forcing them to rethink their activity as well as through the creation of new tools and training methods. In order to improve the cost-benefit ratio, from May 2011 we started a shorter learning course with only two days in the classroom, offered to about a dozen professionals together, for which we have not yet evaluated the impact.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Our project has been shown to be feasible and well-accepted by Italian pediatricians and dietitians. We hope that it will help effective change in the management of pediatric obesity, by reducing all modifiable barriers to a healthier lifestyle and by motivating and increasing selfefficacy of professionals dealing with obesity [64].

The data collected by the primary care participants suggest both the ability of the training project to change clinical approaches of these professionals and the program’s feasibility in primary care settings. The steady positive feedback observed among PCPs and the reduction of BMI z-scores observed among their patients treated with our FTE program were presented at the 3rd National Conference on Nutrition in Children in Verona (Italy) in 2010, winning two awards, as well as an award at the 20th Annual Congress of the European Childhood Obesity Group in Brussels in 2010 [65,66]. This leads us to believe that our procedure could represent a significant contribution to the effective prevention and treatment of childhood obesity in primary health care, even if presently the reviews on this topic do not include any evidence-based programs to increase motivation of health care professionals in treating obese children [33].

Our FTE program has raised considerable interest for its low cost and small investment of time as well as for its acceptance by families and Italian Pediatricians: thus 9 groups of nearly 410 PCPs from other towns (Naples, Milan, Reggio Emilia, Rovigo, Perugia, Terni, Forlì, Cesena, Modena) joined the project and requested a second course for 2012, and others (Palermo, Cosenza, Catanzaro, Monza, Lecce, Roma, Brescia) requested a first workshop or a two-day course.

We present these results to the scientific community to attract the attention of medical professionals and public health institutions to a low-cost Family Therapeutic Education intervention to face a problem of epidemic proportions in a moment of economic crisis. Finally, we must not forget that obesity cannot only be approached from a medical point of view. Contrasting the current “toxic and obesogenic” environment requires a profound commitment on the part of the scientific community and new courageous political decisions [67].

7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all our children and their families, who for more than twenty years, despite the emotional teasing and a frustrating food restriction, shared with us the effort to find a possible and sustainable solution for their problems.

We also would like to acknowledge the precious contribution of our participants, especially those who collected and sent clinical data resulting from the implementation of the study.

ABBREVIATIONS

BMI: Body Mass Index BMI z-score: BMI Standard Deviation Score D: Dietitian PCP: Primary Care Pediatrician EP: Endocrinologist Pediatrician

NOTES

#Corresponding author.