Urological Complaints and Sexual Abuse: A Case Control Study Identifying Multiple Urological Complaints in Relation to Sexual Abuse History ()

1. Introduction

Sexual abuse (SA) is defined by International Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect as “a social and medical problem in which a child under the age of consent is involved in an act resulting in sexual satisfaction of an adult or connivance of such an act” [1]. The frequency with which children are exposed to sexual advances from adults varies according to the definition of abuse, the age range studied, and the methods of ascertainment. The prevalence of SA is estimated to be 12% to 25% for females and 8% to 10% for males [2].

In 2007, for the first time in a large cohort study, SA was causally related with urinary urgency, frequency and nocturia for males and females, using the Hill-criteria (1965) for proving causality [3,4]. Before and after this publication, several investigators found an association between a history of SA and urological complaints [3, 5-13]. Voiding complaints, dysfunctional voiding, urgency and frequency were mentioned to be correlated with SA most frequently. Several studies found no relation with urinary tract infections [6,14]. Recently we established a correlation between synchronic complaints in multiple domains of the pelvic floor and a history of SA [15]. In this study we compare female patients visiting a urological out patient clinic with and without a history of SA. We investigated if the abused patients report more or less voiding complaints, UTI’s and lower abdominal pain than those without SA. In addition we established if the SA-prevalence in female patients visiting our out patient urological clinic was comparable to the percentage of 22.7% found in females visiting our university outpatient pelvic floor center [15]. Because we hypothesize that SA can lead to pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) and PFD can give several synchronous urological symptoms, we wonder if patients with SA have more synchronous urological complaints.

2. Methods

Over a period of 2.5 years a consecutive series of 1383 new female patients of 18-years or older visiting our outpatient urological university clinic were asked to fill out a self-administered questionnaire evaluating referral indications and urological complaints (see Appendix). The construction of the database and the self-administered questionnaire were approved by the local Institutional Ethics Committee. It was conducted by the principle investigator (HWE, an urologist-sexologist) to evaluate female sexual dysfunction [16,17]. All females received a letter explaining the objectives of the study and were kindly invited for collaboration. The self administered questionnaire consisted of two parts. The first collected data about demographic characteristics and medical history, the second part included referral indications, the urological complaints, sexual dysfunction and a possible history of SA. If relevant, patients were allowed to mention more than one reason for referral.

A retrospective database study was performed to identify two groups: those with (cases) and those without a history of SA (controls). Comparisons between proportions were made using Pearson’s chi-square test or Armitage’s trend test; continuous variables were compared by student’s t-test and, where appropriate, analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences were considered significant when the two-tailed p-value was <0.05. Data analysis was carried out using SPSS for Windows version 16.0.1 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). The outcome measures were: 1) The comparison of the frequency of voiding complaints, UTI’s, lower abdominal pain, hematuria and incontinence in respondents with (cases) and without SA (controls); 2) The reported percentage of female patients presenting at our university urological outpatient clinic with a history of SA; 3) The number of urological symptoms presented at the time of referral by respondents with a history of SA.

3. Results

After reading the letter explaining the objectives of the study 436/1383 patients (32%) were willing to participate. All 436 gave written informed consent, 304 (70%) questionnaires were properly filled in.

1) More than half of the females with SA presented with voiding complaints (32/51, 63%, p = 0.18), incontinence (31/51, 61%, p = 0.10) and urinary tract infections (27/51, 53%, p = 0.22). However, comparing the data of respondents without SA: voiding complaints (133/253, 53%), incontinence (122/253, 48%) and urinary tract infections (110/253, 44%), we found no significant differences with regard to specific complaints. Considering lower abdominal pain (20/51, 39%, p = 0.16), hematuria (17/51, 33%, p = 0.13) and colic pain (7/51, 14% p = 0.98), we also found no significant differences between the two groups (Table 1); 2) Fifty-one respondents confirmed SA. This means that 17% (51/304) of the new female patients visiting our outpatient urological reported a history of SA; 3) Using the Armitage’s trend test (0.14, p = 0.004) to compare the reported the total number of urological complaints as reason for referral to the urologist, shows that patients with SA significantly report more synchronous complaints as reason for referral Table 2.

4. Discussion

The 17 % prevalence rate of SA in females visiting our urologic outpatient university clinic corresponds to the percentages found in other specific populations in the Netherlands (10.9% - 23.5%), meaning that this percentage of cases with SA is comparable with SA in other Dutch populations[15,18-22]. The populations and prevalences are listed in Table 3. In a previous study we found out that in an inquiry before the first visit to the urologist

Table 1. Reported complaints as reason for referral in the patients with SA compared to those without SA.

SA + = patients with sexual abuse history; SA − = patients without sexual abuse history; p = p-value.

Table 2. Number of complaints reported as reason for referral to the urologist.

SA + patients with sexual abuse, SA – patients without sexual abuse. This table shows that the patients with SA report more symptoms than those without (Armitage’s trend test 0.14 (p = 0.004) for 4 complaints or more).

Table 3. Prevalence of sexual abuse among females in the Netherlands.

*7.9% (146/1845) for 872 boys and 989 girls combined. This survey mentions a three to four time higher prevalence among girls, but no gender specific data is given. Recalculation of a 3 times higher prevalence for 108 out of 989 girls versus 36 out of 872 boys gives an estimated prevalence of 10.9% for girls only.

70% of the patients with a history of SA disclosed it [23]. The question asked in the questionnaire, “Did you have negative sexual experiences in the past” is of course not equal to “did you experience sexual abuse in the past”, but in the Dutch language it is considered to be similar. This is confirmed by the responses of patients: all patients admitted abuse, and 13 out of 14 patients described the type of negative sexual experience as sexual abuse [23].

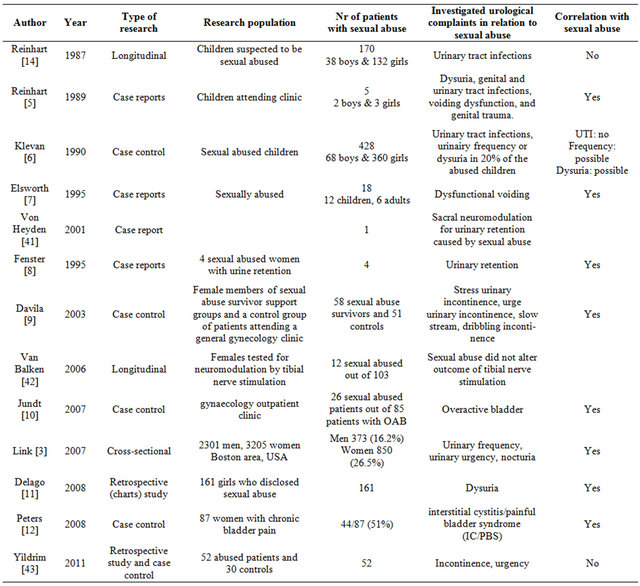

In this sample of patients, most with urological complaints, we found an association between a history of SA and urological complaints, namely a higher percentage of voiding complaints, incontinence and urinary tract infections in the SA group compared to the controls, but the differences were not significant. Several authors found a relation between SA and urological complaints, some didn’t. These studies are listed in Table 4. Despite the pre-existing urological complaints in both groups, patients with a history of SA reported significantly more synchronous urological complaints as reason for referral. Perhaps PFD is an explanation for the synchronous urological complaints. Davila et al. reported significant more pelvic floor related urological complaints like dribbling, slow urinating stream and stress incontinence [9]. In the study from Link et al., in which a causal relation between sexual abuse and over active bladder (OAB) was proven, a short review of the biological pathway was given [3]. They summarize that anxiety and behavioural responses to stress involve complex neural circuits and multiple neurochemical components. Acute and chronic stress due to abuse can alter these circuits, their neurochemical components, and bladder function [24,25]. In animal models stress changes bladder histology en physiology [26-30]. Link et al. also mentions a role for corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF), a primary neurotransmitter expressed by neurons within the central stress network [3]. CRF is expressed by neurons within the pontine micturition center and within regions in the spinal cord that form part of the micturition reflex pathway [31,32]. This assumes that CRF influences bladder function. Besides the above mentioned biological pathways, in concordance with Davila’s observation of pelvic floor related urological complaints, we hypothesize that pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) is another link between SA his

Table 4. Investigated urological complaints in relation to sexual abuse history.

tory and voiding complaints. The pelvic floor is known to be an integrated structure, influenced by psychological and physical causes. A higher prevalence of synchronous multiple pelvic floor complaints, like micturition, defecation and sexual pain, are seen in patients with sexual abuse history [33]. The pelvic floor comprises several layers, including the pelvic diaphragm (levator ani and coccygeus muscles) and the urogenital diaphragm. Each diaphragm has its own 3D shape and position with regard to the internal pelvic organs. The urogenital diaphragm consists of a deep layer, the perineal membrane, and a superficial layer, consisting of the bulbospongiosus muscle and the ischiocavernosus muscle. The levator ani muscle is made up of the iliococcygeus, pubococcygeusand puborectalis muscles. Together with the urethral and anal sphincters, these muscles play an important role in preventing complaints of micturition, defecation, sexual dysfunction, prolapse and/or pelvic floor pain. The development of one of these complaints is referred to as PFD [34]. It has been hypothesized that patients with PFD have voiding difficulties due to a higher tone at rest of the pelvic floor [35-37]. Many of them have episodes of obstructive urinating complaints. As in benign prostate hyperplasia, long-lasting bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) can lead to OAB symptoms [38]. Obstruction-induced changes in the bladder are of two basic types. First, the changes that lead to detrusor instability or decreased compliance are clinically associated with symptoms of frequency and urgency. Second, the changes associated with decreased detrusor contractility are associated with further deterioration in the force of the urinary stream, hesitancy, intermittency, increased residual urine, and (in a minority of cases) detrusor failure [39]. Pelvic floor physiotherapy can be used to treat pelvic floor related BOO and thus relieving OAB symptoms [40]. Unfortunately randomised studies describing improvement of urological complaints in SA survivors treated with pelvic floor physiotherapy are not available. Still, we are convinced that SA can lead to PFD (e.g. pelvic floor overactivity) resulting in BOO, resulting in voiding symptoms and later on in storage symptoms (OAB). This suggest that functional complaints as dysfunctional voiding, incontinence and urgency will be more often associated with a SA-history than complaints with a clear cut aetiology such as hematuria or colic pain. Our Pelvic Floor Research Group reported about the correlation between synchronic pelvic floor complaints in multiple domains of the pelvic floor and SA [15]. In that cohort several patients did not have any urological complaints, but had difficulties with defecation, sexual dysfunction and/or chronic pains; in other words not all patients with a history of SA necessarily have urological complaints. In this study one patient with SA was referred because of an abnormal finding on ultra sound or CT scan, but had no urological complaints. A recent study including 238 patients with micturition, defecation and/or sexual problems, showed that 72% had an elevated pelvic floor rest tone [36]. As much as 56% of them had complaints in three domains of the pelvic floor. This also indicates that a history of SA can reveal itself in other, non-urological complaints.

This study has several limitations. Confounding is a limitation in all case-control studies. As with all casecontrol studies we measured a retrospective exposure (SA), although the exposure is random in the cases and the controls are from the same base population. A possible confounding are underlying psychiatric diseases, which were not mentioned by the cases or controls or use of medications which are not mentioned. Some medications can mask certain urological complaints. A bias in this database is the definition of voiding complaints. The database and inclusion of patients was started before the publication of Link et al. in 2007, in which urgency, frequency and nocturia were causally related to SA [3]. In our database urgency, frequency, nocturia and other voiding complaints are all grouped together. An attempt to redefine voiding complaints in the database by separating urgency, frequency and nocturia was not successful, because the type of voiding complaints was not specified in the questionnaire. This is the major bias of this study. Another bias is selection bias, because of a 32% response rate, is possible that a lot of patients with sexual abuse chose not to respond, what can alter the outcome, introducing a self selected sample. Those who responded may have been different from non-responders, making it difficult to generalize our findings to the entire Dutch female urological patient population. Because our prevalence of SA is comparable to other Dutch populations, as mentioned in Table 3, introduction of a self selected sample is less probable. Also, the use of a selfadministered non-validated questionnaire is a limitation. There are several possible explanations for the low participation rate of 32%. A major part of the patients who were willing to participate may have been embarrassed by the content of the questionnaire. In addition, subjects had to be actively recruited by the urologists and residents. In practice, each new female patient had to be asked if she had received the letter explaining the objective of the study. While some females expressed themselves negatively with regards the content of the study, the recruitment was not always adequately done by all the involved doctors. Undoubtedly, this has contributed to the relatively low participation rate. While they might be distracted, embarrassed, or feel compelled to complete it, we asked the participants to fill out the questionnaire at home and not during their appointment in the hospital. So, they were asked to return it by mail or to hand it over at the second visit. The latter again required a proactive attitude of the urologists and residents. This means that probably not all patients who had filled out the questionnaires were asked to deliver it properly. It would have been better to “overshoot” the number of distributed questionnaires to collect a lager sample. In our sample, twenty patients mentioned no urological complaints at all. They were referred because of abnormalities found on ultrasound imaging or CT-scan. One out of these twenty mentioned a history of SA. One of the major problems in studies on SA is the lack of agreement on the definition and description of SA, like child abuse, rape, or intimate partner abuse. Women forced to engage in oral sex with a perpetrator may have very different pelvic floor problems compared with women who had forced intercourse. Additionally, a sexual abuse experience that includes fondling is very different from a sexual abuse that includes intercourse, and can have a different impact for the functioning of the pelvic floor. So, analysing sexual abuse as a homogenous experience can influence the outcome of this study.

Patients with SA reported more synchronous complaints as reason for referral than patients without SA. We think that PFD gives a range of urological complaints (voiding complaints and storage complaints), explaining the larger number of synchronous urological complaints per person in the SA-group. One may hypothesize that a large number of urological complaints per person in a female patient points to a higher chance of a history of SA. In our opinion urologist should always ask their patients for SA. By addressing the issue, treatment of the urological disorder may improve with understanding of underlying psychological and physical issues from the abuse. Multiple complaints as reason for referral and pelvic floor dysfunction are indicative for a history with SA and should alert the urologist to ask for it.

5. Conclusion

No significant correlation between SA and voiding complaints, incontinence nor lower abdominal pain was found. The prevalence rate of SA in female patients visiting our university urological outpatient clinic was 17%. These abused females mentioned more synchronous complaints as reason for referral at their first visit than the non-abused.

Appendix

Questionnaires:

1) Date of birth:

2) Do you have a partner: Yes/No

3) How many children do you have:

4) Do you smoke? Yes/No

5) Do you have:

• Vascular or heart problems Yes/No

• High blood pressure Yes/No

• Diabetes Yes/No

• Neurological complaints Yes/No

• Psychiatric complaints Yes/No

6) Do you menstruate?

• Yes, regularly

• Yes, but not regularly

• No, I haven’t had a period since a few months

• No, I haven’t had a period for more than a year

7) Did you have negative sexual experiences (sexual abuse) in the past? Yes/No Would you be willing to provide some more information about this? _________________________________________________________________________________

8) What medication do you currently use?

_________________________________________________________________________________

9) Did you have any surcical procedures in the past? If yes, please list them here

_________________________________________________________________________________

Urological Complaints (More Than One Urological Complaint can be Filled)

10) Pain in the region of the kidney? Yes/No

11) Blood in urine? Yes/No

Microscopic (not visibly red) Yes/No

Macroscopic (bloody urine) Yes/No

12) Urinary tract infection(s) Yes/No

13) Voiding complaints Yes/No

14) Incontinence Yes/No

15) Abdominal pain Yes/No

16) Abnormalies on radiological examination Yes/No

17) Refferd by other physician to the urologist, but no urological complaints Yes/No 18) Other, please explain:

NOTES