The Effect of Youth Coaching Styles on “Winner, Non-Winner” and “Loser” Scripts in Young Athletes ()

1. Background

Eric Berne, the founder of Transactional Analysis (TA), believed that young children were born “princesses and princes” until interactions with adults turned them into “frogs” [1]. Also, the same author documented how children form a life position script by the time they reach seven years of age [1]. Scripts are internalized conclusions created by children based on their immature interpretations of external events that are occurring around them. Traditional influences during childhood including parents, teachers, coaches, and peers, model ways for young people to manage the external world that exists around them. Problematically, when authority figures and friends fail to teach and support the child, the child ego-centrically blames themselves for the emotional and behavioral acting out observed in the role models. In other words, children at this age, who have not reached the Piaget stage of “formal operations” are unable to consider that these significant others are acting inappropriately because they lack the perspective necessary to consider alternative explanations for the behavior [2]. Instead, the child on an athletic team assumes that everything is their own personal fault. This is analogous to each player solely blaming themselves for a team loss. Unless this perception error is corrected by a coach or parent, the child’s misinterpretation and self-blame (and accompanying shame) will likely become a foundation piece to the formation of loser and non-winner life scripts.

Transactional Analysis as a Coaching Tool

Transactional Analysis has been used as a means of understanding coaching behaviors for many years [3]. The TA approaches to coaching typically focus on how coaching styles influence the interaction of the coach’s ego states and the player’s responding ego states. Ego states include the Adult, Parent and Child aspects of the personality. For example, the Adult in TA theory is the “information only” part of the mind. As a coach, the Adult is expressed via learning techniques, strategies, and tactics of games [4]. In 2002, Slater noted that young athletes, even elite athletes, frequently drop out of team sports when coaches focus extensively on the Adult Ego State of children [5]. For example, coaches attempting to access the Adult aspect of the player require players to be devoted to mundane activities including diet, efficient time management, practice schedules, repetitive rehearsal of scripted plays, memorizing the playbook, understanding the rules of the game, and adhering to the rules of the team.

Conversely, Nespoli observed that when coaches allow players to “have fun”, they are developing and attending to the TA Child Ego State [4]. Walker insisted that young players on sports teams have many of their basic Child ego states fulfilled via recognition from others, receiving approval, belonging to a group, freedom to be creative, and, of course, the simple need to “play” [6].

However, youth coaches primarily occupy and coach from the TA Parent Ego State [7]. The Parent aspect of the ego can be either nurturing or critical. The Parent aspect of coaching is a state of active monitoring of what players should and should not do. The healthy Parent imparts guidance to athletes and develops responsibility without manipulating or playing psychological “games” [5]. Freed concluded that coaches who operate from the Parent state best serve their teams by imparting competence, and achieving team goals with some degree of pleasantness [8]. Sadly, many coaches misinterpret the goal of a coach as one who teaches through unkindness, impatience, and aggression. These Critical Parent coaching styles are born from strict judgmentalness and are particularly problematic for young players who desire to please the coach, but frustratingly learn that they cannot.

The Nurturing Parent and Adult Ego States focus the coach to ask that each player do their best and be open to learning and teaching of new skills and information about the sport [5]. A coach operating from the Nurturing Parent and Adult states sees losing as an opportunity to point to the player’s improvements and plan to modify skill deficits and interfering attitudes via better teaching in practices before the next game [5].

2. Coaching Styles

Emotional climates (or team atmospheres) created by parenting and teaching styles act as filters through which adolescents interpret parents’ and teachers’ behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs [7] [9] [10] [11]. The same interpretations are made by players receiving youth coaching. If adolescents who play sports feel respected, accepted, and supported by the coach, they carry out achievement-related tasks in a more autonomous manner, and they are more likely to internalize the educational values and beliefs of coaches, parents, and/or teachers or [12].

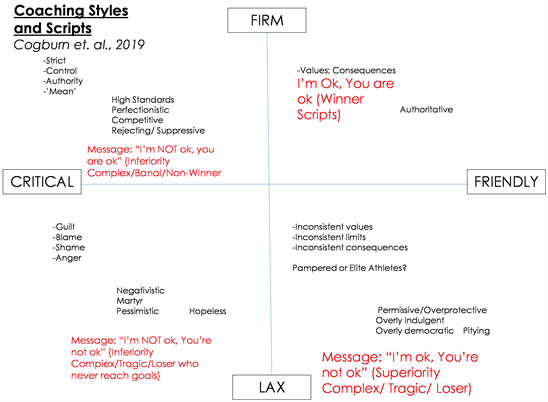

To better understand the youth coaching model, Appendix A is provided. The term “Structured” is used to describe coaches who are highly structured and have clear expectations. These coaches resist chaos and are often rigid and strict. Rules are important to them. “Critical” is a construct that expresses the amount of warmth provided to players. “Unstructured” illustrates a lack of rules and predictability that often lends itself to chaos on teams. “Positive” suggests that the coach is warm, emotionally supportive and actively kind to players.

It is a benefit to children and adolescents involved in sports to be coached with a structured and positive coaching style. Children coached from this style are prepared to develop optimally in regard to mental health. Rarely will they present as being overly macho, anti-social, anxious, but they would instead be expected to have enough self-confidence and self-control to be effective athletes [7].

2.1. Winner Script

The Positive-Structured coaching style strongly influences and nurtures the winner script. The Positive-Structured coach has clear expectations for players and the players clearly understand them. Consequences are clearly defined and are seen as teaching moments instead of punishment by players. There is no yelling or verbal abuse. Encouragement is generous and focused on what the player is doing correctly. The coach’s goal is to teach the player how to improve instead of winning. Players and parents perceive this coach as fair and a good role model. This coach has very good self-control and is not prone to anger. A Positive-Structured coach is flexible, usually teaching in multiple formats and adapting to the learning styles of the individual player. Motivation is provided in a variety of ways, although punishment is rarely used. There are fewer coach-parent conflicts with this approach.

A “winner”, in TA parlance, is not someone who does not lose [13]. A winner is someone who is authentically oneself and can be trusted. Winners are athletes who do not set themselves up for failure. They have no patience for feelings of inferiority or superiority, avoid helplessness during the competition, and do not blame others [14]. Winners, while born dependent and vulnerable, move into independence and interdependence throughout childhood and adolescence. In youth sports, these players work hard to become the best version of themselves and are less interested in winning than performing with a high level of skill. They are adroit at effectively managing their emotions during contests, rarely becoming the victim of emotional highs and lows. Throughout life, these are resilient children and believe themselves to be quite capable while having enough self-esteem to take chances across a wide spectrum of endeavors.

2.2. Loser Script

The Critical-Unstructured coach and the Positive-Unstructured coach evoke the loser script in young athletes (Appendix A), which, for the purposes of this paper, is an expected manifestation of poor youth coaching: The Critical-Unstructured coach is viewed by players as moody and unpredictable. This coach uses emotional manipulation to control players and get results. Specifically, the frequent use of guilt, blame and shame is problematic, and praise is uncommon. These coaches frequently hold themselves out to the team as martyrs and insist that players acknowledge all of the sacrifices that they are making for the team (e.g., leaving work early, buying equipment, missing important family gatherings, etc.). They constantly complain, even when the team is doing well, yet provide little teaching. This coach will always find a problem, regardless of team and player successes, and are viewed by others as pessimistic. Any small failure in practice can result in their patented “sky is falling” response. They typically focus on goal-setting as a means to “win” instead of improving the performance of each athlete. Players who only consider success as the goal are prone to constant comparisons among teammates and seldom attend to skill development [15].

The Positive-Unstructured coach is another contributor to the loser script. This coach has no rules, few expectations, and is comfortable with chaos. This coach is not process-oriented, so players are taught very few skills in practice. Moreover, players are unlikely to be required to have sufficient physical conditioning in order to play. Their goal is to have fun, seldom compete, and always be a friend to the players. Practices are viewed as social gatherings and very little teaching takes place. It is very important to this coach for the players like him/her and they frequently perceive conflict as something to be avoided at all costs. It has been noted that even elite athletes who have been pampered by youth coaches are developmentally immature as evidenced by their macho attitudes and entitlement behavior [16].

Even with highly elite athletes, the Positive-Unstructured coach will influence children to blame others, while excusing themselves, and manipulate teammates and coaches if possible. These players seldom live in the present, and experience a range of emotions from extreme sadness and self-pity when ruminating on the past, to high anxiety when considering future competitions. Losers are afraid to try new things and maintain what Karen Horney referred to as the “the phony self”, in which young athletes use rationalization and intellectualization as excuse-making behaviors [17]. The lack of an authentic self often results in a lifetime of problem relationships, little personal growth, and avoidance of challenges.

2.3. Non-Winner Script

When considering the Critical-Structured coach, one sees a coach on the extreme end of demandingness combined with an overall lack of warmth. Players report them to be unapologetically controlling, competitive, and perfectionistic while always maintaining extremely high expectations. The Critical-Structured coach is punitive when players do not perform well and is often verbally demeaning, prone to forcing players to perform difficult physical tasks as punishment for mistakes. Parents often describe this coach as having a Type A personality [7]. They may lack empathy and are impulsive with a low frustration tolerance. The goal is to win, and they attack this goal with great fervor. Parents and players may view this coach as a having a “short fuse”, often becoming aggressive and upset over small things. Time urgency drives them, and any activity that wastes time in practice is not tolerated. This coach thwarts the athlete’s potential and increases frustration by not accepting an athlete’s limitations [4] [7]. Praise is authentically used as a means to manipulate the player into conforming, and pleasing the coach is the ultimate coaching goal. Players from this coaching style often underperform [4].

Someone with a non-winning script is a “middle-of-the-roader” plodding along from day to day, not seeking victory while also interested in avoiding losses. This young athlete avoids risk and plays it safe in sport and life. This TA script pattern is often referred to as “banal”. These are athletes that will never be comfortable being a team captain or fulfilling any leadership role, yet they play well enough to continue to make the team. The Non-Winner script is associated with a Critical-Structured coaching style.

3. Conclusions

One of the greatest challenges of agencies that provide sports programs for children and adolescents is selecting good coaches who will not psychologically damage their players. Childhood coaching experiences, like parenting, are powerful influences on normal and abnormal development among athletes across the lifespan. Indeed, it is quite common for adults to look back on their lives and recall how a coach pushed them toward a lifelong narrative of success, indifference, or failure. The authors addressed how youth coaching influences an athlete’s self-image of being “OK” or “Not-OK”, while simultaneously teaches children the “Winner”, “Non-Winner”, and “Loser” scripts.

Since failure and setbacks are inevitable aspects of life, “OKness” and the “Winner” script infuse perseverance in the face of adversity. This requires honest self-reflection and error correction rather than maladaptive perfectionism and the blaming of self and others. Winner scripts instill a sense of determination and self-efficacy instead of indifference and helplessness. Specifically, the Positive-Structured coach is preferred to foster these adaptive traits and behaviors in young athletes. This coaching style views mistakes during a game as an indispensable opportunity for learning and creates a team atmosphere where players are willing to take risks and make mistakes. Through these permissions, the relationship between coach and player allows for true meaning, honesty and respect, allowing the child or adolescent to achieve optimal performance.

Conversely, ineffective and negative coaching styles are burdensome to children and adolescents who play sports. They diminish self-efficacy and self-esteem at an age when young people are absorbing increasing rates of adult information and feedback and fostering them into assumptions regarding likely outcomes of relationships in their adult lives. These loser and non-winner scripts that develop in childhood often lead to self-sabotage and frustration across the lifespan because of distorted self-beliefs. These faulty beliefs appear to follow adolescents in adulthood where they create an insecure foundation for life. Too often permeating adults who avoid risks, enter into self-defeating life choices, and either fail or lack the success observers would have predicted based on their biological and environmental assets.

Even with excellent coaching, no child will be one hundred percent “Winner”, and with bad coaching, it is unlikely that a team member would be viewed as one hundred percent “Loser” or “Non-winner”. However, it is reasonable to believe that good coaching elicits more “Winners”, and therefore the Positive-Structured approach we described provides a suitable benchmark. As Bangambiki Habyarimana observes in The Great Pearl of Wisdom, “If success is a miracle then you must be the miracle worker” [18].

Appendix A.