A Preliminary Geographic Analysis of the Paula Oberbroeckling Case ()

1. Introduction

Eighteen-year-old Paula Oberbroeckling went missing from her northwest Cedar Rapids apartment in the early morning hours of July 11, 1970. According to her roommate, she was going out to get cigarettes from a nearby gas station. Paula never returned from this errand. Her badly decomposed body was found in November 1970 along the banks of the Cedar River with hands and feet bounded by rope. The Oberbroeckling family gained a measure of closure when Paula received a funeral and was buried days after her body was found. What Paula’s family does not know is what exactly happened to Paula between the time she left her apartment and the time that her body was discovered. In 2017 this case remains an open, unsolved homicide. The purpose of this paper is to aid the search for the persons responsible for Paula’s death and to help the Oberbroecklings find out what happened to their loved one after she disappeared from her apartment in the summer of 1970.

This paper uses the tools of environmental criminology to analyze the case and to identify persons potentially able to supply more information and to shed more light on what may have happened to Paula Oberbroeckling after she disappeared. Three hundred and six potential persons of interest (PPI) identified by Chehak [1] and other sources are mapped, comparing the PPIs’ 1970 home addresses (or other significant geographic anchor point1) with the location where Ms. Oberbroeckling’s remains were discovered in the 1900 block of Otis Road in southeast Cedar Rapids. The social and geographic analysis, supplemented with sociopolitical and economic background information to provide context, elevates the profiles of eleven PPIs. At the time this paper was written, these individuals stood blameless for Paula’s death, but the analysis suggests that they or their surviving relatives may be able to tell us more about what happened to Paula Oberbroeckling after her disappearance. The Oberbroeckling family has waited 47 years for answers about Paula’s murder. This family deserves answers so that it can finally gain a measure of closure and peace for the loss of their 18 years old relative that in 1970 had her entire life ahead of her.

There is a larger significance to this research: thousands of families around the world feel the pain of the Oberbroecklings who lost a family member under unknown circumstances. Criminologists estimate that at least 200,000 murders have gone unsolved since the 1960s in America alone, leaving family and friends to wait and wonder [2] . The geographic methods used in this paper could be revised or replicated and applied to any unsolved murder where there is sufficient documentation in the form of FBI and police reports, autopsy records, news articles, photographs, and interviews with people who were related to or knew the decedent. Any success gained by this current analysis holds promise that other families, enlisting the aid of professionals, could potentially find answers to what happened to their loved ones, thus gaining a measure of justice and peace as they continue to grieve.

2. About Paula Oberbroeckling

Paula Oberbroeckling was born in 1952 to Carol and Jim Oberbroeckling of northeast Cedar Rapids, Iowa.2 Paula attended neighborhood schools for elementary and junior high, then attended Cedar Rapids Regis, a nearby Catholic school, for one year. After her freshman year at Regis, she was craving a more diverse education than the Catholic school could provide, so she transferred to Cedar Rapids Washington High School ( [1] : p. 18). Washington was a longer commute but had a more diverse student population, drawing from affluent northeast neighborhoods as well as poorer ones in southeast Cedar Rapids. Beginning her sophomore year at Cedar Rapids Washington, she started dating young Blacks attending the school, including Robert Williams, a basketball player for Washington High’s 1969 state championship team ( [1] : p. 31).3

Interracial dating was something relatively new to Cedar Rapids in 1970, the year Paula graduated from high school. It was a national trend that began in larger cities on both coasts but eventually spread to Middle America and to places like eastern Iowa where it slowly gained a grudging sense of acceptance [3] [4] [5] [6] . Students at Washington appeared to accept the practice, except for a small cluster of Black women who felt that white women were beginning to deplete their supply of suitable Black mates ( [1] : p. 307). In the community outside of school, the practice met with considerable resistance. Paula’s mother, Carol Oberbroeckling, was furious at her daughter for dating the Black basketball player, going so far as to designate certain household utensils as “Paula’s” to separate these from the utensils of Jim (father), Carol, and Paula’s siblings, fearing that Paula might be spreading some contamination to the rest of the family. Tensions rose to the point that Paula left home to live on her own; this was while she was a senior at Washington High ( [1] : p. 157). However, at the time of her disappearance―the summer following her graduation―she had reportedly broken up with Robert Williams and was dating a white boy named Lonnie Bell ( [1] : p. 57). She was considering moving back home to her parents’ house at the time of her death; in part, this was to separate herself from people she believed to be harmful peer influences, and also to save money so that she could attend modeling school. Paula had entered a modeling competition at a local store, and her good looks gained her victory over her competition ( [1] : p. 24). Encouraged by this win, she had plans to become a model.

At the time of her death, Paula discovered that she was pregnant. She believed that the baby was fathered by Robert Williams, whom she had seen only sparingly since his graduation in 1969, one year before her own graduation. Her current boyfriend (in 1970), Lonnie Bell, was upset when he learned of Paula’s pregnancy. Convinced Williams was the father, Lonnie believed the situation was a sign of Paula’s disloyalty to him, and infidelity ( [1] : p. 250). The evening she disappeared, the couple appeared to be arguing about something ( [1] : p. 81). Investigators at the time believed that Lonnie’s rage and jealousy could have been sufficient reasons for him to kill Paula. Only a few hours after Paula left her apartment for the last time, Lonnie was there asking to take back some of his possessions. Thus, when Paula went missing, Lonnie Bell quickly emerged as the prime suspect.

On July 10, the night of her disappearance, Paula was last seen with Lonnie Bell and a young man known to both Paula and Lonnie, a mutual friend named Ben Carroll. (Ben had dated Paula years before). The three attended a concert at the No Where Lounge on Center Point Road featuring Austin and Garf, a Hiawatha, Iowa band with a minor hit that locals thought could break into the low end of Billboard’s Hot 100. When the date ended, the two young men dropped off Paula at her northwest side apartment which she shared with Debbie Kellogg at about 12:30 A.M. Lonnie Bell and Ben Carroll both stated to police that they did not see Paula again after this encounter ( [1] : p. 84-85). A friend of Paula’s reportedly saw her about 1:00 A.M. in downtown Cedar Rapids where she was having car trouble ( [1] : p. 81). A witness saw a girl matching Paula’s description in southeast Cedar Rapids about 5 A.M ( [1] : p. 259). The car Paula was driving (which belonged to her roommate) was found near a store on Mt. Vernon Road in a no parking zone during the daytime hours of July 11 ( [1] : p. 74). Rumors circulated about where she had disappeared, but there were no more credible reports of her whereabouts until her body was discovered in late November 1970.

3. The CRPD Theory

The theory of the Cedar Rapids Police Department (CRPD) emerged after a murder took place at a southeast Cedar Rapids poker party in February 1971, about seven months after Paula went missing. At the party, Perry Harris shot his good friend Ernie Jordan three times in the back for no apparent reason and then waited for police to come and pick him up. A story told by community activist Art Pennington explained why Harris shot Jordan and linked Jordan’s slaying to the Paula Oberbroeckling case. As Pennington told the police, Jordan and Harris were pimps for a Cedar Rapids chiropractor named Thomas Sturgeon. Prostitutes were brought into Cedar Rapids from Chicago, and some of the women needed abortions; Sturgeon provided those abortions, at a house at 810 5th St. S.E. After becoming pregnant by Robert Williams, Paula went to Sturgeon on the night of her disappearance seeking an abortion. Sturgeon began the operation, but something went wrong as Paula was bleeding uncontrollably and lost consciousness. When she could not be revived, her body, from Sturgeon’s perspective, needed to be disposed of. The doctor solicited help from Perry Harris and Ernie Jordan. Harris and Jordan tied Paula’s legs and hands together with rope in case she regained consciousness. The two men discreetly removed Paula’s body and placed her close to the Cedar River near the railroad tracks on Otis Road. Sturgeon owed the two men a large amount of hush money for having handled Paula’s body without being seen by anyone. It was believed that Sturgeon had paid more money to Jordan than to Harris, and this led to the dispute which flared up at the card party. Perry Harris was angry that he had not received his full share of the compensation. It should be noted that variations of this story were circulated by police informants in the southeast Cedar Rapids neighborhood known as “the ghetto”. However, the basic outline of the story remained relatively constant over time: there was a botched abortion which led to Paula’s death, and her body needed to be ditched, quickly, at a remote site ( [1] : p. 396-404).

4. Critics of the Theory

Critics of the CRPD theory have long suspected that there was more to the story than has been officially reported. They found it hard to believe that a narrative with so many verifiable details did not result in a vigorous investigation culminating in an arrest and a conviction for Paula’s murder. They pointed out that not all details had been followed up and investigated fully; for example, it appeared that not all of the eyewitnesses to Paula’s abortion had been interviewed. They further believed that people knew more about the case than they had previously revealed and that somewhere someone had information that could either support or refute the police department’s working theory. Dissatisfied with a situation she viewed as untenable, a writer named Susan Taylor Chehak took on the case in 1999. A Cedar Rapids native, Ms. Chehak knew Paula and was a classmate at Washington High. She gathered police files, FBI reports, photographs, newspaper articles, and tracked down and interviewed some of the potential persons of interest in the case, including some not previously interviewed by either the police or the press. She crowd sourced the investigation by publishing all of her documentation online along with a downloadable e-book about the case. Ms. Chehak hoped that the documentation might jog someone’s memory about undisclosed details; and by publishing it all online, she allowed other investigators to take on the case if they wished. She was hoping that a collective effort would accelerate the solving of this case so that the Oberbroeckling family could finally find justice, closure, and peace.

5. Environmental Criminology

The theoretical perspective used to analyze the Oberbroeckling case is called environmental criminology, the study of crime and criminality related to particular places and how people―both criminals and victims―shape their activities spatially. Because it was a late developing field, it is still today a body of knowledge not widely familiar to the public or even to many social scientists. Environmental criminology’s roots are often traced to the early work of L.A.J. Quetelet [7] which revealed that property and violent crime rates varied among French departments (counties). He sought to explain these variations by looking at social factors such as age, gender, social class, and climate. In the Chicago School of sociology in the 20th century, Ernest Burgess [8] similarly noted varying rates of juvenile delinquency in a small city in rural America. In certain wards within this town, he found that geography provided a more robust explanation than race and social class for the varying delinquency rates (see also [9] [10] [11] [12] ).

Today environmental criminology is an umbrella term used to encompass a variety of theoretical approaches which relate to the spatial and temporal components of crime. In general, the approach is concerned more with the environment in which crime occurs and less with individual offender traits. There is a particular emphasis on the place where the crime occurred. The place of the offense is a significant historical fact that suggests a great deal about the person or persons who committed the crime. According to routine activities theory [13] [14] [15] [16] , one of the ideas under the umbrella of environmental criminology, the place of the crime often represents an opportunity encountered in the course of the routine, customary and familiar activities of the offender. Thus, the place of the crime is embedded within an offender’s habitus or comfort zone. Cohen and Felson [13] believed that the place where the crime occurs is the confluence in space and time of a likely offender, a suitable target and the absence of a capable guardian to prevent the crime from occurring. Cohen and Felson defined routine activities as any recurring activities that provide for our daily needs whether of biologic or cultural origin. The tasks we undertake to maintain ourselves at school, work and play are our routine activities. As Paula’s case appears to have been an opportunistic attack, the application of this theory could help explain some of the facts presented by Chehak in her book and on her website. For example, applying this theory to Paula’s case, Paula appeared to be a suitable, vulnerable target clad only in what some described as a “nightgown”4 in the ghetto district of Cedar Rapids with no friends to support her. A second environmental criminology theory, the geometric theory of crime [17] - [22] puts even more emphasis on place. According to geometric theory, the offender’s primary search areas for criminal opportunities coincide closely with their “activity spaces”, that is, a configuration of their ongoing and relatively patterned behaviors according to personal space-time metrics. Because a victim’s activity space may overlap with those of offenders many times per day, we are all at risk multiple times daily to become victims of crime [23] . The most impressive application of this theory is the geographic profiling work of D. Kim Rossmo [24] [25] and Maurice Godwin [26] [27] [28] . Geographic profiling uses the locations of a connected series of crimes to determine the most probable area of offender residence. This methodology is most often applied to serial cases of murder, rape, arson, and robbery, but it may be used for any string of crimes by one person that involves multiple scenes or other geographic characteristics. Investigators using such tools search for the location of the offender’s known space-time anchor point, typically a work address or home residence; but it can also be a current or former activity node such as a paramour’s house, a workplace, or other established node for that individual. The approach can be adapted to searches for offenders when there is only one victim, or where there is at least some reasonable suspicion that a single victim may potentially have been the victim of a serial offender. Susan Taylor Chehak ( [1] : p. 600) notes that another young woman was murdered in a space and time relatively close to Paula’s death.

As Andresen [29] noted, the place where the crime occurred is a critical dimension of criminology that for many years was not emphasized enough, coming into vogue only as recently as the 1970s and 1980s. The law, the offender, and the victim were given much more strident examination because these three elements were thought to be necessary conditions for a criminal event to occur. However, Andresen states that there were two reasons why place became more important after 1970. First, the three areas mentioned above had dominated the criminological literature, leaving us with relatively little knowledge about the spatial dimension of crime. Second, early environmental criminology studies appeared to fill this void, suggesting that spatiotemporal patterns of crime were remarkably predictable. Thus, environmental criminology was poised to enhance and expand our understanding of the law, offenders, and victims. As a means of prioritizing possible offenders, however, it was too new of an idea to gain acceptance at the time of Paula’s death. Though it emerged as a tool for criminologists to reevaluate crime data beginning in the 1970s, environmental criminology theories were not widely applied to help analyze crime cases until the use of geographic profiling in the years after 2000 [25] [27] [30] [31] .

6. Data Analysis

Three hundred and six potential persons of interest (PPI) in the Oberbroeckling case were identified from a close reading of Chehak [1] and related sources. Any individual encountered in this book that could be reasonably linked to possible knowledge about Paula’s disappearance and murder in any way was logged and then became the object of further data gathering. PPIs stand guilty of no crime, but they, or persons in their social network, may know important pieces of information that could help solve the case. It should be noted that the term PPI is not used in this paper in the same way that it is used in law enforcement. In law enforcement, the term means someone who may in the future come under reasonable suspicion or probable cause of having committed a crime. In this paper, a person designated a PPI is simply someone whose name was mentioned in the documentation provided by [1] or in related sources, and may, possibly, have some information to contribute toward finding out what happened to Paula between the time of her disappearance and the time her body was found.

Each identified PPI was measured along a number of variables. The number of times that the individual was mentioned in [1] , an e-book that functioned as a searchable database, was the variable measuring the PPI’s social distance to the Paula Oberbroeckling case. The more mentions in that book, the closer the PPI is socially to the victim. The distance of the PPI’s 1970 home address, or other anchor point, to the site of Paula’s remains on Otis Road is the geographic variable. This method is an adaptation of geographic profiling techniques typically used to investigate serial murders to a case where there is only one identified victim. It draws on the nearness or least effort principle in psychology, whereby a person who has various possibilities for action will select the one requiring the least expenditure of effort [32] . It recognizes that an offender’s distance to the crime scene is often short [33] . Further, the precepts of environmental criminology would suggest that those who live nearby the body disposal site would not only find it convenient, but would also be familiar with the area or would have reason to regularly visit it―for example, to go fishing in the Cedar River or to travel to a nearby workplace. Additionally, the quadrant of Cedar Rapids in which the person lived (NE/SE/NW/SW)5, the minutes of driving distance to Paula’s body on Otis Road (in MapQuest or Google Maps), and the gender, race, and age of the PPI were measured, if available. Besides Chehak [1] , information on PPIs was gleaned from the now unpublished website of Susan Chehak, the Cedar Rapids Gazette, and City Directory archives at the Cedar Rapids Public Library; a national newspaper archive based in Cedar Rapids; and books and articles consulted on Cedar Rapids history and culture [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] .

Demographic data collected showed that males made up 74 percent of the PPI population and females 26 percent, based upon an examination of surnames. For the PPIs whose race could be determined based on surnames or press accounts, 52 percent were Black, 47 percent were White, and 1 percent were Hispanic. Age data were available for 67 of the PPIs. Ages ranged from 15 to 58 with a mean age of 22.4 years. Most PPIs lived in southeast Cedar Rapids. Ninety percent of PPIs lived in southeast Cedar Rapids with the remaining 10 percent living in one of the other quadrants of the city.

CRPD detectives working the case admitted that when called upon to investigate a murder, they looked immediately to family and close associates as possible suspects. They believed that they would find that the killer was someone embedded in the victim’s immediate social network. As investigators prioritized the time spent on Paula’s case, they chose to spend their resources looking at the people that were close to Paula socially. Thus, a working assumption of this study is that the closer a PPI was to Paula socially, the more times that PPI would appear or be mentioned in Chehak’s e-book, considering that police were searching Paula’s social network6 and police reports were reproduced verbatim in the e-book or web site. The second key variable in this study, the geographic distance of PPIs from where Paula’s remains were discovered, was determined by comparing each PPI’s 1970 home address/anchor point with the place where Paula was found, estimated to be 1959 Otis Road S.E., using the online tools Google Maps or MapQuest.7 A second working assumption of this paper is that the closer a PPI lived to the place where Paula was found, the more likely it is that that the PPI potentially possesses information about the case which may still yet be relevant to investigators. This idea draws on a geography of crime literature which suggests that crimes often occur in relatively close proximity to the home of the offender [25] . Even if not the offender, such PPIs may be able, at the very least, to shed light upon why the particular spot on Otis Road was selected as the disposal site, information that could help the Oberbroeckling family find closure and peace as they continue to grieve. Further, according to the principles of environmental criminology, the disposal site would be close to the offender’s usual activity spaces, places where he/she routinely transverse during daily life.

To avoid false positives in the data analysis, an Index of PPI Involvement was constructed. The first score in the index was the PPI’s ranking according to the social distance variable. Points were given to PPIs based on the following formula: first rank (with most mentions in Chehak’s e-book) achieved a score of 15; the second rank earned a score of 14; the third rank received a score of 13; the fourth rank garnered a score of 12; the fifth rank was assigned a score of 11; and so on until the fifteenth rank which was assigned a score of 1. Ranks 16 - 306 were given a score of zero. The same ranking system was used to rank PPIs according to the geographic distance to the case. The PPI that lived (or had an activity node) closest to 1959 Otis Road SE was assigned a score of 15, the next closest PPI received 14 points, the next closest 13 points, and so on. Ranks 16 - 306 were scored as zero. An Index of PPI Involvement overall score of 5 or greater, after adding the social and geographic scores, indicated a PPI with an elevated profile. An overall score of 5 or above also successfully captured all PPIs that lived 0.7 miles or less from the Otis Road discovery site.8 The purpose of constructing this Index was to achieve a balancing of social and geographic factors and to avoid a possible false conclusion based upon studying either the social or the geographic data by itself. As this Index was constructed, the profiles of eleven PPIs who scored 5 or above on the Index were elevated: Lonnie Bell, Lucious Prince, Robert Williams, Debbie Kellogg, Perry Harris, Larry Tobin, Steve Tobin, Wendell Beets, Ben Carroll, Frank Pusateri, and Robert Talyat (see Table 1).

1) Lonnie Bell. The appearance of Lonnie Bell at the top of the list is no surprise to anyone familiar with the Oberbroeckling case. He was Paula’s boyfriend at the time of her death. He was with her the night she disappeared. That evening the couple appeared to have a quarrel, which led to Lonnie dropping Paula off at her apartment around 12:30 A.M, an earlier than usual end to their date. Later that night, upon learning that Paula was missing, Lonnie went to the southeastern district of Cedar Rapids seeking information about Paula’s whereabouts ( [1] : p. 159). Additionally, he spent time with Paula’s family to aid the search for Paula in the days and weeks after her disappearance ( [1] : p. 75). He spent time with the family as well in the days after Paula’s body was found. These actions would appear to be those of a genuinely concerned boyfriend who was trying to

![]()

Table 1. Index of PPI involvement in the Paula Oberbroeckling case.

find out the truth. At other times, Bell came across to the police as behaving suspiciously, as when he refused to take a polygraph test regarding what he knew about Paula’s disappearance. He was evasive when questioned by police. Detectives were also aware that within a week after Paula’s disappearance, he was in Minneapolis attending a rock concert; this was interpreted as evidence of Bell’s callous disregard or lack of concern about Paula’s plight ( [1] : p. 85).

2) Lucious Prince. Lucious Prince makes a late appearance in Chehak’s copious narrative. Near the end of her extensive documentation, evidence surfaced that Paula may have had a third friend or paramour that she reached out to on the night she disappeared (someone other than Lonnie Bell or Robert Williams). Chehak identifies this person as William Rose of 119 13th St. SE in Cedar Rapids ( [1] : p. 560). Rose is unranked on both social and geographic criteria, and it is not known for sure if he was an associate of Lonnie Bell. Lucious Prince enters the fray due to a story told by Cheryl Titlbach which was also known to Debbie Kellogg. Titlbach, well connected to the southeast drug scene, said that William Rose had beaten up Paula with the help of her future husband, Lucious Prince and that Paula died as a result of the beating. Her body had been disposed of ( [1] : p. 561). Prince is unranked on social distance but stood out because of the 306 PPIs, Prince was one of four that lived closest to the Otis Road discovery site, only 0.5 miles away, one minute away by car.

3) Robert Williams. The appearance of Robert Williams near the top of the list is something expected by veteran investigators of Paula’s case. Williams was the young man who played basketball for Washington High and dated Paula during his senior year. After high school, he left town for a year to pursue a college basketball career which never got off the ground. After that, he returned to southeastern Cedar Rapids where he has lived ever since ( [1] : p. 154). Being close to the “ghetto” scene, it is thought that Williams knows more about Paula’s death than he has told investigators. He was at an all-night party at John Ely’s house the night Paula disappeared. Ely, an influential ultra-liberal politician, was known to “alibi” young black men, that is, to say (falsely) that they were at Ely’s home in order keep them from being implicated in crimes that they might have committed. On the way back from the party, Williams hitched a ride with Ben Carroll ( [1] : p. 158).

4) Debbie Kellogg. Debbie Kellogg was close socially to Paula’s case but not geographically.9 Nonetheless, she was Paula’s roommate at the time of her disappearance, and it has always been the impression of investigators and Paula’s family that Kellogg knew much more about the case than she ever told to anyone. It was Kellogg’s car that Paula borrowed to run her late-night errand. The car was found in a no parking zone on Mt. Vernon Road the next day. She moved out of the northwest side apartment she shared with Paula within hours of Paula’s disappearance, an action that has aroused the suspicions of many. She intimated that Paula had a secret life that was unknown even to those such as herself who lived with her ( [1] : p. 109).

5) Perry Harris. In a revealing interview conducted by Susan T. Chehak, Perry Harris, the man featured prominently in the CRPD’s working theory of the case, told Chehak that he disputed a number of specific points in the CRPD theory; these contested points, in turn, suggested that white people were involved in the placement of Paula’s body near the Cedar River ( [1] : p. 412-421). He said, first of all, that he did not participate in Paula’s murder, or dispose of her body. Paula did not undergo an abortion. He was convinced that she reached out to a third paramour, thus appearing to validate the story told by Cheryl Titlbach. And he had strong doubts that a black person would have transported Paula to the Miller Lane site because it would have required someone to travel southeast on Miller Lane, a dead end road. It would have required someone to drive onto Miller Lane and dump Paula’s body and then to have backed down Miller to exit the area on Otis Road. The other alternative, after placing Paula in the brush, was to drive to the end of Miller Lane, which dead ends, turn around, and then to travel back up it to exit to the area on Otis Road. Both options were ones a Black person would not likely choose because it would draw immediate attention and suspicion. As Harris told Chehak: “…when you got off that road (Otis) and went up further, let’s face it. We’re talking about 1970. If you took your black butt up there, you was through gambling. And I mean you could get shot or the police would be there. You didn’t go on white people’s property in the middle of the night. That would be somebody who knows exactly and knows who the people are and where things are to be able to go up there. That ain’t some somewhere somebody stumbled into. Somebody would have to know somebody to go up there” ( [1] : p. 421-422).

6) - 7) Larry and Steve Tobin. Larry and Steve Tobin lived together about 0.6 miles from where Paula was found, one minute away by car. In one story that circulated in the southeast side, Paula was last seen alive at an undisclosed southeast address in the presence of Steve Tobin ( [1] : p. 336). The Tobins were arrested in a July 4, 1970, altercation at a southeast Cedar Rapids bar, which almost became a race riot. Cedar Rapids, overall, prides itself on its exemplary race relations. Residents have taken a measure of credit for the fact that most racial incidents have been handled peaceably. However, the city admittedly had a close call in this 1970 episode one week before Paula left her apartment for the last time. In the early morning hours of July 4 police were investigating the beating of a man in front of the Mirror Lounge and traced the men involved in the beating to the Brown Derby, a bar at 601 12th Ave. SE.10 When officers tried to arrest Steve Tobin and others, a near-riot broke out involving about 100 persons; the rioters contended, apparently, that the Tobins were unjustly arrested ( [1] : p. 337). The Tobin brothers were arrested in this incident by white police, and their sense of anger and resentment, very fresh only a week later, may have fueled their participation or interest in Paula’s case.11 Revenge might have motivated them to get involved in some way to harm Paula or to help dispose of her body.

8) Wendell Beets. In a variation of the story told by Art Pennington, (one told by another police informant) Paula went to Dr. Sturgeon’s office in late June 1970 and received what appeared at the time to be a successful abortion. On July 11, Paula started hemorrhaging. She called Dr. Sturgeon who told her that he would get a nurse and meet her at the Eagle’s Store parking lot on Mt. Vernon Road, not far from where her car was subsequently found. Dr. Sturgeon then contacted a friend of his who told him that Wendell Beets had a sister who was home on leave from the Medical Corps and was either in the WACs or the Air Force. Wendell Beets’ sister12 then met Dr. Sturgeon and they, in turn, met Paula at the Eagle’s where they took her to an unknown location where she continued to hemorrhage and subsequently died. Dr. Sturgeon then called Ernie Jordan and told him of his problem and Jordan enlisted the aid of Perry Harris, and they then got rid of Paula’s body for Dr. Sturgeon ( [1] : p. 450). This police informant indicated that Wendell Beets had full knowledge of the whole case, including his sister’s activities in the attempt to stop the hemorrhaging. Beets draws interest here not only because of his possible intimate knowledge of what happened to Paula but also because of his geographic proximity to the Otis Road site as he is one of the top ten PPIs out of 306 that lived closest to where Paula was found.

9) Ben Carroll. In what could be a headline finding of this study, Ben Carroll had the dubious distinction of being the only PPI in the 306 person population to be ranked among the top PPIs in social distance to the case as well as geographic proximity to the place Paula was found in late November 1970. Carroll ranked #14 in social distance and #11 in geographic distance, living only 0.7 miles or two minutes by car from where Paula’s body was discovered.13 Carroll gave police interviewers a Marion, Iowa address; however, his parent’s home at 1724 15th Ave. SE where he may have lived during high school was nearby the entrance of Van Vechten Park, the Cedar Rapids public park where Paula’s remains were discovered. If he lived there for a long time,14 he would be thoroughly familiar with the park and the area near the railroad tracks where Paula was found. Importantly, Carroll dated Paula briefly in years past and was with her the night that she disappeared. He along with Lonnie Bell dropped Paula off at her apartment on July 11. He gave a ride to Robert Williams after Williams left John Ely’s party. Overall, he was vague about his whereabouts after leaving Paula at her apartment and needed to be interviewed by police a second time to resolve discrepancies in the first interview ( [1] : p.158).

10) Frank Pusateri. Mr. Pusateri was married to and then divorced Paula Oberbrockling’s aunt, Ardyth Haynes ( [1] : p. 463). On the surface, he had all the trappings of a leading citizen and community activist. His father was a respected southeast side businessman, and Frank emulated his father by becoming the President of the Oak Hill-Jackson Neighborhood Council in 1968. But there were hints of a darker side to the family. In a Gazette article published the year Paula died [40] , Frank was cited by the city for operating a foster home that did not live up to city code. The home was run out of the basement of the family residence at 1728 15th Ave. SE, which is next door to where Ben Carroll’s parents lived and just 0.7 miles or two minutes by car from the place where Paula’s body was found. Researchers were interested in the Gazette story because they heard speculation that Paula was held on the southeast side, in someone’s basement, prior to being killed.

11) Robert Talyat. Talyat has no mentions at all in Chehak [1] but is someone interesting because he lived just 0.7 miles from 1959 Otis Road SE. His bad public behavior did not apparently come out until five years after Paula died. Beginning in 1975, southeast residents complained to Linn County health authorities about the poor maintenance and upkeep of two homes that his family owned at 1013 and 1017 17th Ave. SE. In September, 1979, the county gave the Talyats a deadline to clean up the properties which came and went without any effort by Robert Talyat to improve the homes. The county contracted with a private company, Zinzer, Inc., to demolish the structures in late 1979 [41] [42] . Talyat was known to fish in the Cedar River near where Paula was discovered; in 1961 his name appeared in the Gazette after he helped save five boys who were swimming in the river and could not return to shore by themselves [43] . Talyat is also interesting because a link has been established between the Talyats and Ben Carroll’s family. Richard Talyat, Robert Talyat’s son, was the best man in the 1974 wedding of Ben Carroll’s wife’s sister [44] .

7. Discussion

The best time to have investigated this case was in the days and months immediately following the date that Paula disappeared while leads were warm and memories fresh. There were a number of reasons why the case was not investigated more thoroughly at the time Paula died.

The primary reason that the police department was reluctant to further investigate the case in the early 1970s was due to the completely false idea that Paula, provocatively and scantily dressed on the night of her disappearance in the Cedar Rapids ghetto, essentially got what she deserved―that is, her suggestive attire had invited a sexual attack.15 This is a classic case of blaming the victim for her own demise. Paula’s relatives were infuriated by the lack of compassion of the police as they investigated, in a manner that could be construed as perfunctory, the facts surrounding Paula’s disappearance. Though feminism was coming into vogue during the 1970s, much of America’s heartland lay mired in old, sexist ways of thinking, and that appeared to be the case among the detectives assigned to the case: both were males born in the 1930s. What’s more, Art Pennington’s story of an abortion gone bad stood the test of time as few credible alternatives emerged. Pennington was a former pro athlete, a solid citizen and a reliable source for investigators, and CRPD was willing to let his story be the end of the matter. He also, in telling his story, confirmed the predominant patriarchal attitude toward the crime within CRPD. The last words uttered by Pennington to Chehak in an interview were “So I guess she (Paula) asked for it” ( [1] : p. 404).

Furthermore, CRPD’s working theory was believed to be the final solution to the case because all three of the major perpetrators―Ernie Jordan, Perry Harris, and Thomas Sturgeon were either dead or sent off to jail. Jordan died in the 1971 poker game; Harris was convicted and sent to prison for Jordan’s death, and Sturgeon went to jail in the 1970s. With all of the perpetrators gone, there was no longer any case to prosecute. What most residents of Cedar Rapids did not know was that Harris was only jailed for five years for Jordan’s murder. He was back in town by the mid-1970s after having cooperated with police to solve hundreds of Iowa crimes ( [1] : p. 418). This short sentence―hard to imagine in today’s law and order climate―nonetheless transpired and Chehak was probably quite surprised to find and interview him in the 2000s for her book. Except for one possible small scrape with the law in the 1990s, Harris had apparently been clean and had flown under the radar of the detectives who worked on Paula’s case, both of whom retired in the 1980s.16

A further compounding factor that kept investigators away from digging deeper into the circumstances of the case was the fact that further investigation would only have aggravated the racial tensions already prevalent at a time when an extremist group, the Black Panthers, was actively recruiting young men in Cedar Rapids. The Panthers’ ideology suggested that police were “pigs” and that all incarcerated Blacks were political prisoners. The group advocated for self-defense, including violent means if necessary, especially if victimized by police harassment. So, CRPD officers felt threatened by the group and hoped to tamp down racial tensions to the greatest extent possible. Not prosecuting the Oberbroeckling case had the practical effect of lowering the temperature on the race issue, which was what both the police and city officials wanted at that point in time. Cedar Rapids leaders had worked hard to promote good race relations. Judges and prosecutors worked hard to reduce sentences and city administrators worked as well as they could with civil rights organizations to promote a sense of fairness in all its dealings with residents of the southeast Cedar Rapids ghetto. The people in that area, the Oak Hill-Jackson community, were an insular, tight-knit community that had years ago traveled en masse from a part of Iowa where they lived with little Jim Crow discrimination. They came from the coal mining town of Buxton, in Monroe County. The mining operation started in 1900 and lasted until 1922 when coal seams in the area were depleted. At the height of the coal boom Buxton grew to about 5,000 residents (though some estimates trended upward to 10,000), with a reported 54 percent black population. As such, it was the largest unincorporated community in Iowa and was believed to be the only place in the state that was majority-black. Buxton had no municipal government, no law enforcement, and no staff to maintain the roadways and streets. Consolidated Coal Company, which owned the town, hired its own security guards to look after the company’s investments [35] [37] [38] . Moreover, Consolidated Coal Company established many progressive policies. There was no overt segregation in Buxton. CCC treated blacks and whites equally in employment and housing. Schools were racially integrated and taught by black and white teachers. The town contained many black professionals and was sometimes referred to as a Black Promised Land [35] . Only after moving away to Waterloo, Cedar Rapids, Des Moines, and places out of state did residents experience for the first time the culture shock and the hard realities of a segregated America and the kinds of discrimination that blacks in the South, as well as in the North, had to endure [35] [36] [45] . Not being familiar with discrimination, the proud residents of Oak Hill had a long history of pushing back hard against any kind of discrimination through civil rights advocacy organizations17, and this accounts in part for the relative peace in Cedar Rapids, though underneath it all was a tension between the tightly knit southeast residents and the white community. That tension, it should be noted, continues to the present day as the ghetto has yet to fully recover from the economic blow of major plant closings in the 1950s which were a source of good-paying jobs. Jobs and opportunities have not returned since that time [35] .

8. Conclusions

Of the eleven PPIs with elevated profiles, five are now deceased. Surviving relatives may still be able to help investigators, though the passage of time will make any helpful recollections difficult. Six are still alive, but the close-lipped nature of the Oak Hill neighborhood and the strong social bonds between families make it less than likely that anyone will volunteer new information. Nonetheless, it is hoped that publication of this paper will be one more catalyst for renewed interest in the case. Someone out there knows something. Advanced forensic tools not available in 1970 could be enlisted to assist in cracking the case.

An anticipated criticism of this study is that the methodology used amounts to an exercise in racial profiling. This paper could be criticized as a skewed analysis because the PPI population was largely young and Black, and lived closer to the Otis Road disposal site than did most other residents of Cedar Rapids. Ninety percent of the PPIs studied lived in the southeast quadrant. That being the case, it could be argued that the Black community, mostly confined to the southeast side in 1970, is under indictment for Paula’s death simply because it happened to live near where Paula’s remains were found. However, precepts of environmental criminology suggest that the place where a crime is committed is an undeniable historical fact of great significance in identifying potential offenders. The body disposal site suggests that someone very familiar and comfortable with this area chose it as the place to put Paula’s body. A place knows no race, and a place can be symbolically significant to both whites and blacks, or people of other ethnicities. Critics should also consider that the individual primarily responsible for Paula’s death, according to the CRPD theory, was a white man, Thomas Sturgeon. Five of the eleven PPIs with elevated profiles in the statistical analysis were white and the headline finding of the paper casts more attention upon Ben Carroll, a white friend of Paula’s whose family lived only 0.7 miles away from Paula’s remains, two minutes away by car. Living next door to the Carrolls was Frank Pusateri, a white man that ranked high on the Index of PPI Involvement. Moreover, the variable, social distance, was intended to be a counterweight to the geographic analysis, realizing that most of the PPIs would come under at least some suspicion simply because of geography―they happened to live close to Otis Road in southeastern Cedar Rapids.

Furthermore, a known weakness of environmental criminology studies is that the data analysis may not be entirely accurate when all possible persons of interest have not been identified. In Paula’s case, for instance, researchers do not know what they do not know. There may be one or more persons, unknown to us at present, who were not identified by Chehak [1] or other sources that were suspected of involvement in Paula’s murder. These new potential suspects, in turn, would impact, and change, the data analysis.18 Consequently this paper is a work in progress, a preliminary analysis. Our understanding of what happened to Paula will improve as more data comes in. The reason Chehak crowd sourced the investigation was to try to help stimulate the collective memory of the event in the hopes that someone who knew details that might assist the investigation. Anyone with new information is encouraged to come forward. It may be that someone who grew up in Cedar Rapids and since then moved away may remember a small detail that could be of significance in solving the case.

The geographic investigation, as it advances to a more mature phase, would stress the idea that space is not only a physical phenomenon but a psychological one as well [25] [46] . Subjective psychological perceptions of distance can be as critical as the objective physical space involved. Stea [47] for example suggested that one person’s perception of distance can be influenced by several factors in addition to actual physical distance, including: the relative attractiveness of origins and destinations; number and types of barriers separating points; familiarity with routes, and the perceived attractiveness of routes. As a geographic analysis progresses and one or more of these factors can be reliably measured, the data analysis becomes richer as a result of tracking these psychological aspects of space.

The Oberbroeckling case could be advanced if the possibility is embraced that Paula was one of several persons killed by a serial offender. Maureen Farley’s body was discovered across the Cedar River from where Paula was discovered; this crime occurred after Ms. Farley disappeared from her rooming house at 522 10th St. in September, 1971 ( [1] : p. 600). Karen Streed, of 112 7th St. SW turned up missing in 1971; her home address was only 2.7 miles from where Paula was found [48] . Naomi Wilson, the girlfriend of Colbert Beets, vanished without a trace from her southeast side home at 1618 13th Ave. SE in April, 1981. Her abandoned car was retrieved from 2727 16th Ave. SE, less than one mile from 1959 Otis Road SE [49] . If Paula’s case is conceptualized as one murder among several committed by a serial offender, then advanced computer packages such as Rigel might be used to help prioritize PPIs based upon the program’s data output. These programs use geographic-psychological algorithms to help predict the most likely residence of an offender. Packages such as Rigel are employed almost exclusively in multiple victim violent crimes where the offender is unknown to police and the public.

Appendix

Iowa and Cedar Rapids Maps

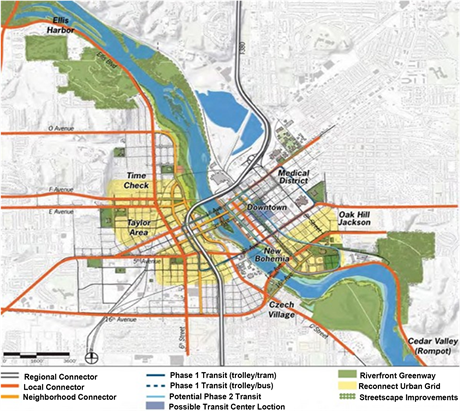

Cedar Rapids Map. The green shaded area between the Oak Hill-Jackson neighborhood and Cedar Valley, east of the Cedar River, is Van Vechten Park, where Paula’s remains were found. The brown shaded road alongside the Cedar River is Otis Road, SE.

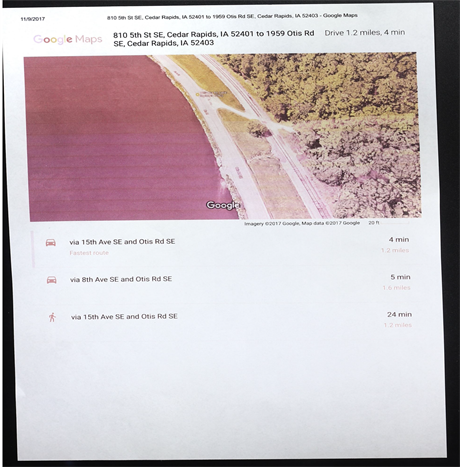

Southeastern Cedar Rapids. This is a Google Maps photo of the crime scene at 1959 Otis Road SE, which is marked in the center of the map. Miller Lane travels southeast off of Otis Road. The green shaded area is in southern Van Vechten Park.

1959 Otis Road, SE. This is a Google Maps view of 1959 Otis Road SE from the standpoint of the Cedar River looking northward. Otis Road and the railroad tracks run generally to the northwest in this photo. Miller Lane can be seen running southeast from Otis Road. There is a small tree between the railroad tracks and Otis Road; this is believed to be very close to where Paula’s body was found.

NOTES

1Examples of an anchor point are the residence of a paramour, parent, grandparent, workplace, recreational facility, bar or restaurant. If no 1970 address was available, the address chronologically closest to 1970 was used.

2Cedar Rapids is located in East Central Iowa. It is the seat of Linn County. See the maps appended to this paper.

3Robert is no relation to Rick Williams who played basketball at Washington and later at the University of Iowa ( [1] : p. 32).

4Paula’s sister said Paula was wearing a “bra dress”, a short dress with bra and panties sewn into it ( [1] : p. 75).

5These quadrants are based on Business Highway 151, which runs southwest to northeast (if traveling toward Dubuque and the Mississippi River), and the Cedar River, which runs northwest to southeast. See the Cedar Rapids maps in the Appendix to this paper.

6Sociologically speaking, a social network consists of family, friends, friends of friends, and acquaintances.

7In MapQuest, pointing the indicator directly over the spot where Paula was found produced the address of 1959 Otis Road S.E.

8Seven more PPIs who registered a composite score of 5 or higher are not analyzed here due to a lack of citations in Chehak [1] ; that is, they appeared to lack meaningful connections to Paula’s social network. They were of interest primarily due to geography―by living fairly close to 1959 Otis Road SE.

9The apartment Ms. Kellogg shared with Paula in July 1970 was far away from Otis Road, but we checked a previous residence in Southeast Cedar Rapids. This residence was still far enough away for Ms. Kellogg to remain unranked according to the geographic variable.

10Some media reports said that the persons involved in the attack were traced back to the Cougar Lounge, 329 9th St. SE.

11Larry Tobin was released on the night of his arrest. Steven Tobin was held for questioning for at least one more day before being released.

12Chehak identifies this person as Alvernia Beets Franklin ( [1] : p. 602).

13When Ben Carroll was nominated for the Air Force Academy by Senator John Culver in 1970, 1724 15th Ave. SE was listed as Carroll’s address [39] .

14The Carroll family is listed in the Cedar Rapids City Directory as far back as 1956. His family originally lived at 2423 Bever Ave. SE, 2.2 mi or 7 minutes away from 1959 Otis Rd. SE.

15One of the rumors circulating in the ghetto was that Paula had been raped first and then killed.

16There were two Perry Harrises in Cedar Rapids, we could not find out which one was arrested in June, 1995 for drug trafficking.

17The Ellis Park pool incident of 1941, when a young black men was denied entrance to the public pool (per segregation policies in effect at the time) led to the development of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in Cedar Rapids [35] [45] .

18Maurice Godwin’s geographic profile of the South Louisiana Serial Killer, Derrick Todd Lee, was 20 miles off because Lee had killed one victim that Godwin did not know about. Once that final victim was discovered and placed in his model, his analysis showed that the suspect lived in St. Francisville, Louisiana, which was where Lee was swabbed for DNA in May 2003 [31] . Had authorities taken Godwin seriously early on (they didn’t) several deaths could have been prevented.