1. Introduction

One of the new influences of economic theory is the idea of crossing other theories from different social sci- ences such as: psychology, sociology and anthropology to combine concepts and methods with the economic theory [3] . A common place between these disciplines is the treatment given to the concept of happiness or well- being except with economy, in which the assumptions on behavior and decision making, like the expected utility and individual economic rationality, are questioned by these new cross-disciplines.

As an example of this Herbert Simon in his declaration for the Nobel Prize said: “There can no longer be any doubt that the micro assumptions of the theory―the assumptions of perfect rationality―are contrary to fact. It is not a question of approximation; they do not even remotely describe the processes that human beings use for making decisions in complex situations”. This opens a path for the reconsideration of concepts largely accepted as truth in the economic theory.

2. Utility

The outcome from crossing some of these disciplines has resulted in the study of the Experimented Utility, from which we have acquired a greater approach to individual well-being than from the revealed preferences method [3] . L. J. Savage [4] demonstrates with probability models the violation of the expected utility assumption; this provides the possibility to manifest the development as an outcome of these new theories. There have been considerable contributions to the economic theory, as an example Frey & Stutzer, Kimball & Willis, Kahneman & co-workers [5] - [12] , Vaan Praag [13] - [15] , and Easterlin [16] - [18] .

Mathias Benz rescues three important concepts that allows to discern happiness and unify it with the concept of Utility, in a way that it makes a more ample concept. First: momentary feelings of pleasure and joy usually referred in psychology literature as a positive or negative psychic involvement in a person’s experience, is called happiness. Second: Average fulfillment with life, is regularly called satisfaction with life. Third: Quality of life obtained by satisfying the potential in one’s self, which it may be referred as eudaimonia or “the good life” as an Aristotelian concept.

Thanks to this contributions and advances, some other concepts have been promoted by some economists such as Kahneman [18] , naming a “Decision Utility” as a distinction between experimented Utility and remembered Utility. At the same time Elster [19] considered emotions such as: Self-signaling, achievements, control, and significance to apply as psychological determinants of Utility. Loewenstein [20] incorporates intrinsic motivation, which in simple terms is the fact that a person will do something just for the pleasure of doing it e.g. a hobby. Osterloh & Frey [21] incorporates altruism, reciprocity, and cooperation as important elements of human decision that may determine Utility. Schwarze & Winkelmann [22] as Fehr & Gätcher [23] , used the identity emotion in their studies, Akerlof & Kranton [24] , among others use status, self-esteem, and social recognition as influential variables in decision-making and utility measurement.

2.1. Procedural Utility

This developments in the theory, have led to the creation of other concepts such as Procedural Utility which focuses on non-instrumental factors of Utility, or different processes on decision-making and institutions on which people live and act and independently gain Utility. In this notion, common sense of conscious individuals is important, people have the capacity of being introspective and they value respect, they have self-esteem and pride, their behavior on theory and models is more human-like than the traditional homo economicus.

The sole idea of Procedural Utility emerges from the assumption that people have a sense of being, that is to say people are conscious and care what defines them, what can define them, how can they be defined, how they define through other people, and how they are perceived by others. “This concept incorporates a central axis of social psychology and economics” [25] .

This notion exists because procedures generate important feedback for one’s self. Specifically this feedback appeals to the innate and psychological feelings of self-determination. Psychologists like Deci and Ryan [26] , have identified three innate psychological needs that are essential for psychological satisfaction that determines one’s self.

First, Autonomy: this need includes the desire to auto-organize one’s self’s actions, or “being” one’s self. Second, Affinity or Harmony: This refers to the social desire of being connected to others by feelings, and to be treated as a respectable community member. Third Aptitude or Capacity: This refers to the tendency humans have to control the environment or context that surrounds them, also to experience one’s self as an effective and capable person.

These three psychological determinants have been used and combined to generate a different analysis on consumption behavior, labor and work places, public policies (allocation), politic preferences, taxing efficiency, income redistribution and equity, and in organizations. As an application of this theory, Procedural Utility may be experienced from the interaction between people and institutions that intervene in decision making, such as market mechanisms, democratic decisions and hierarchical institutions.

Bruno S. Frey, Mathias Benz and Alois Stutzer [25] argue about the existence of changes in consumption that come from changes in individual behavior, that play a role in decision and consumption preferences, e.g. consumer boycotts produced by an “unfair supplier process” for a rational change in price. The authors Kahneman, Knetchs, and Richard [10] , investigated these reactions. Some other authors like Konow, Frey and Pommerehne, and Shiller, Boyocko and Korobov, have investigated this phenomenon. In all of these studies that are in an excess demand situation the same individual behavior is perceived [25] .

These kinds of appreciations are also found in other economic fields, for example: when persons are income earners, the most common situation is that they belong to an institution with hierarchical processes. In this context hierarchy means that production and labor are integrated in organizations that are characterized for some kind of authority level. These kinds of institutions are fundamentally the most important from which decisions are taken in society, therefore an important factor in the economy.

Frey and Benz [5] and Benz Stutzer [6] provide empirical evidence on how people gain or lose procedural utility from hierarchy. They propose two ways from which people may acquire income: in a hierarchical system as employees or independently as a self-employed. In this investigation they found that self-employed people gain a greater utility from work that those that are employees, even with controlled variables like wages and working hours. The self-employed seem to appreciate the autonomy of not being subjected to hierarchy independently from the difference in the possible outcomes. This study also found evidence from the hypothesis related to this concept, satisfaction, ceteris paribus, is lower when people are subjected to greater levels of hierarchy. This hints the importance of procedural utility in variables like labor.

The notion of autonomy and having control over decisions in work, are sources of procedural utility. Similar results are found in Blanchflower and Oswald, Blanchflower, Blanchflower, Oswald and Stutzer, Hundley, and Kawaguchi [27] [28] . These and other recent studies use fixed effects panel data regressions, to demonstrate that this changes in general satisfaction with labor, is not perceived as a variation generated by changes on people’s personality. Other type of variable represented as the value of being an entrepreneur like an object of creativity and autonomy is found in a general way in an article by Mathias Benz [28] . Stefan Schneck [1] founds that in the work place being subjected to hierarchy generates negative procedural utility, because it violates psychological precepts that determine happiness, well-being or utility.

Other kind of literature focuses on the concept known as procedural fairness. This concept is more known in the study of laws, and is applied in countries like Australia [29] , this means that in the processes in which people are subjected to in the work place must be considered fair. For example: in case there is a wage cut, it is probable that workers will oppose to this and even feel abused, making this wage cut not to happen, even when the reasoning behind this is a consequence of the market’s behavior and is a rational decision, economically speaking. In these terms Greenberg [2] , found that the process of how a wage cut is made must be considered to be just, to lessen the negative effects.

2.2. Procedural Utility: Evidence from Mexico

The literature focused on labor and organizational theory doesn’t deny that insufficient work conditions can generate disutility, nevertheless aspects like autonomy, influence over work, and procedural fairness, are not taken in account in formal models, for example the one of Aghion & Tirole [30] .

Revising the evidence and empirical applications of this concept, by using a Probit model I’ll analyze evidence of this phenomena in Mexico with the finality to give suggestions on possible applications of processes to improve the workers satisfaction, and as consequence improve the productivity and functionality of a company. In this way this results could be used to demonstrate that in labor organization and in labor as an economic concept Procedural Utility exists with the ambition to enrich further analysis as mentioned before by Bruno Frey, Mathias Benz and Alois Stutzer.

The data used for the regression, contains nationwide results of the Self-reported Well-being Unit or BIARE for the Spanish initials. This unit is applied to people between 18 to 70 years old (one for every household of a subset of the National Survey of Income-Expense household sample), in a period from January to March in 2012, in urban and rural areas. BIARE has 10,654 registered people (5967 women and 4687 are men) with 201 fields that include information about satisfaction with life (from 0 to 10), aspects of life satisfaction, happiness, and previous emotional states experimented before the survey, socio-demographic and socio-economic characteris- tics, among others [31] .

This survey has generated important information, nevertheless hierarchy as a whole concept is not as simple or easy to obtain, so by using the principal components analysis or PCA an approximation to experimented autonomy of a worker is reached. This component named occupations includes a variable created form the aggregated section of the National System of Occupation Classification, which explains the type occupation of every surveyed people according to the National Institute of Geography and Statistics or INEGI, such that occupations classified from 1 to 9 are to be separated from directive jobs like employer or chief and are subjected to more hierarchy in their process. The other component is a variable that takes in account if the worker belongs to a gremial organization, and a dummy variable that incorporates important psychological aspects of work, for example: Do you need to change of work or have a better one?, do you like your current job but need that belter working conditions?, do you need a promotion?, and also how relevant work is for the person which is an aggregated variable from 77 possible components that could be pertinent for each person. See Table 1.

The other variable generated was procedural fairness, approximated by how sociable is an individual in different kinds of contexts, which gives a general image of the social behavior of the person, how much the person searches for social relationships does and how much does this person participates in them. Studies like the ones from Ingham [32] , Newby [33] , and Gross and Bendix [34] assure the existence and functionality of this connection. As well the “accionalist” perspective on work processes, as explained on the Latin-American Treaty of Labor Sociology” written by De la Garza [35] , and with fundaments found on studies by Edwards and Scullion [36] , This connection reflects a social relationship with the person and its work, which approximates the type of reaction a person may have if exposed to processes in the working place and his closeness to the company.

Procedural fairness was calculated by PCA, using reported social life satisfaction called socsatis, which components are: Affective life satisfaction, how many neighbors does the person know by name, how many times does the person gathers with friends, how many times does the person gathers with family, if he had contact by email with: 1 = family that doesn’t live with him or 0 = friends, if the person had contact by phone with 1 = family, 2 = friend, if the person has and participates on social nets, if the person practices a sport where he need to interact with others, and his self-reported satisfaction with family relationships.

In this case four components where found PF1, PF2, PF3, and PF4. Component number 3 (PF3) explains social activity with a negative correlation, while direct communication and expression with other persons is positive. This can be explained by the type of question asked to the persons, the weight on satisfaction for this component changes the variable’s behavior, and nonetheless we can’t omit it. See Table 2.

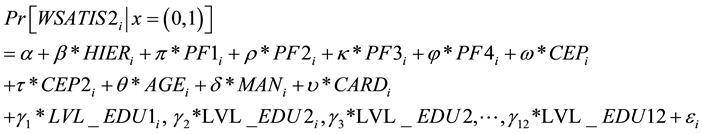

Our dependent variable (WSATIS2) was reduced to a variable with two characteristics (0,1) pertinent to the data distribution, and may be explained by the proxies obtained from the PCA which are: procedural fairness (PF1, PF2, PF3, and PF4), the variable that represents hierarchy to which each person is exposed (HIER), and control variables like: age (AGE), age squared (AGE2), education level (EDUC), if the person has credit card (CARD), sex (MAN), total current expenditures per capita from January to March in thousands of pesos (CEP), this variable squared (CEP2), and a dummy variable (0,1) that tells if the person has or not the education level from 1 to 12 in ascending order (LVL_EDU1 to LVL_EDU12), being 12 a person with a doctorate level of education.

With these variables the sample may be controlled, and could give insight on how self-reported satisfaction in the working place and how procedural utility can be explained for Mexico’s case.

![]()

Table 1. Principal components/correlation for Hierarchy (eigenvectors).

aEigenvalues > 1 significant component; bNumber of observations = 4363; cOwn elaboration with INEGI’s BIARE data. The loss of observations for this case is given by the variable workmat that is the combination of the 77 possible things that an individual may care in the job; some of the people don’t think it’s relevant.

![]()

Table 2. Principal components/correlation for Procedural Fairness (eigenvectors).

aEigenvalues > 1 all are significant components; bNumber of observations = 7349; cOwn elaboration with INEGI’s BIARE data. dBecause of the quantity of variables and components (10) only the most relevant are shown.

Equation (1) is:

(1)

(1)

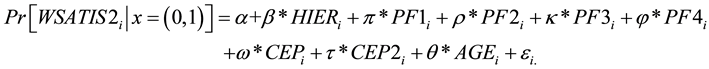

By taking account the dummy variable as 12 different dummy variables, it was found that there was no significant relation between education level and labor satisfaction, this may be generated by the correlations found between education level and total current expenditures per capita. The correlation between the variable CARD, and the PCA that represents hierarchy is negative and sufficient to bias the equation, which can be explained because the hierarchy level, theoretically has almost nothing to do with consumption credit, even though it can be considered as a control variable; also by analyzing the correlation between the variables CARD and CEP, it’s found that CEP in part is explained by credit access or CARD, by this means consumption may be increased or vice versa. The variable MEN, which denotes genre doesn’t affect labor satisfaction, also the variable AGE2 is not pertinent because it was found that there was no limit of age for having a certain probability on work satisfaction, also considering the high correlation between AGE and AGE2, The final equation or Equation (2) takes form to facilitate data interpretation:

(2)

(2)

All variables are significant, and the estimator’s symbols correspond to the theory, literature review and the expected behavior of the variables Table 3.

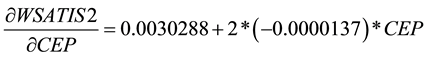

The probability of being subject to more hierarchy, reduces labor satisfaction, while the variables that re- present procedural fairness, demonstrate that the better processes a person is exposed to in labor, the greater satisfaction he will gain. In other hand variable like expenditures and age doesn’t have an important effect over labor satisfaction, none the less it is necessary to understand that to a higher income people are happier, always reaching to a market limit given by the CEP2 variable, that could be considered as the limit value that people give to their leisure time and they are willing to “sell” as labor.

(3)

(3)

The evidence suggests that increasing the income of one person will raise the probability of having more satisfaction in the work place, nonetheless it has a limit where income is equal to the utility it generates by itself,

![]()

Table 3. Marginal effects after probit.

when the limit of 110.5401 Mexican pesos is passed, the more income the person gets the less utility it gains. This can be explained because income itself is not the only determinant of happiness; In other hand the average CEP for a regular person is 13.00039 Mexican pesos, that divided by the limit, results in 8.5 times. In average a labor day in Mexico consists of 8 hours a day, not counting sleeping as leisure but as a necessity, so one day consists of 16 hours. This represents that Mexicans are willing to sell 53.125% of their time before asking for their leisure time compensation, which by the Mexican law must be compensated by the double of the daily income, that makes sense in the way that the worker is not only working more than it is supposed to, but the company is compensating their leisure time. If this doesn’t happens in a strict way labor satisfaction is diminished for the average worker. In the case of this study, only five persons weren’t satisfied with this compensation and these five cases have a lower labor satisfaction than the average. This clearly violates the always truth correlation between income and utility, just by adding a more person-like individual to the equation. The breakpoint, for this not to happen may be suggested on an even greater compensation of leisure time, or a change of working conditions.

3. Conclusions

The evidence obtained by the concepts that generate procedural utility in theory. It is relevant to expose that this investigation’s data base from INEGI, for starters, could improve significantly with time and effort in a way that it could give more pertinent data to the concepts of this investigation and others that may follow the same theory. In other hand, the relevance states itself in the empirical express existence of these concepts, that for the moment this empirical evidence has only existed mainly for European countries, while in America it only exists in the USA, and in Chile [37] [38] . The analysis for this case suggests that more than hierarchy, the treatment and relationship that exists in the labor environment in regard of the psychological perceptions of self-determination theory, is one of the most important aspects.

As an example of the later, some Asian countries like Japan [39] implement a process in which the worker identifies with his job, brand, and factory. The daily exposition to the relevance of the whole over the individual, as well as the constant contact with other workers with morning exercise and other processes may generate a greater general satisfaction with labor, improving well-being, productivity, and encouraging a better working- place environment with the senses of responsibility while appealing to harmony and individual capability, this way provoking the feeling that their participation in the production is relevant at a social level in more than one aspect.

This in conjunction could lessen the negative effect of autonomy generated by hierarchy in labor, if the later may look not very efficient or costly, another relevant way to attend the phenomena, may be by an incentive’s model in the group’s participation on the working place. For example: a guided visit, organized outdoor activity, between many other recreational activities that may reinforce the social bonding with the group, also maintaining a fair model at process level and decision making, and affinity with processes and individuals that participate in them.

About hierarchy, a relevant aspect that could be revised are the effects and contributions of being part of a union, the conditions of belonging to one (sometimes it’s an obligation), and if the benefit of being part of one is actually greater than the cost that implies being in one (including monetary cost). For countries like Mexico examining the processes that are connected with enterprises and unions, and how that determines labor satisfaction may be relevant, given that most of Mexico unions have great influence in many sociopolitical levels that affect decision making and create externalities to productivity.

This doesn’t suggest eradicating the protection workers may find on unions, but to regulate them and find the possibility to implement new justice procedures like procedural fairness that defend the rights of workers, and give a resourceful source of procedures to enterprises, workers and state to improve the workers wellbeing and by consequence those that are dependent on them.

Other case suggests that in developing countries like Mexico, informality is an alternative to formal work, and is probably a determinant of labor satisfaction, given that people may obtain autonomy from being their own bosses and derive utility that way. New incentives for public policies may be found studying the procedural utility and procedures from which individuals are subjected to, and find a why they change from formality to informality and the other way around.

These examples and ideas on procedural utility, and the concept per se, may prove very useful in creating new public policies that can affect happiness which derives to a more efficient way of doing things for everyone involved. This theory and field of study has a lot of potential to change the way science, enterprises, and government think of individuals to how they think of human beings, which makes more complex but assertive decisions based on how humans actually behave.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr. Isidro Soloaga, Geraldine Larissa Villegas, and Arturo Vargas for their support.