1. Introduction

Many studies show that Rural Women’s Cooperatives at Greece play a multitude of social and economic roles in rural societies. The continuously increasing number of Rural Women’s Cooperatives results from the promotion of cooperative entrepreneurship by the public policies. Especially for rural women, market challenges in rural areas are better dealt with through this type of entrepreneurship.

Most of the Rural Women’s Cooperatives produce and sell traditional food products made with raw materials from their regions of activity (oil, wine, milk, eggs, etc.). A smaller number of cooperatives are active in the agro-tourism sector, as well as in the home handicrafts sector, producing folk art items such as embroideries, traditional costumes, and more [1] . These sectors are all involved in the processes of local development and create links between products, landscape and culture of a region. These maintain the local heritage, while contributing to the creation of the cultural identity of a region.

In the modern globalised world, production of traditional food from the female agricultural cooperatives considered innovation and related techniques and technologies at the level of production and processing are relevant to the culture and skills [2] . Certified local products such as organic products [3] and/or certified traditional goods [4] - [6] , which integrate gastronomy, the cooking culture and “cultural symbols” of each region increase the overall value resulting in higher added value [7] .

Despite the positive public policies, Rural Women’s Cooperatives still do face many problems. They lack in issues of implementation and development of innovations, technological updating and improvement of quality, hygiene and product safety [1] .

Taking all the above mentioned into consideration, this retrospective study investigates the entrepreneurial procedure of Rural Women Cooperatives at Greece.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Institutional Background and Policies

In Greece, the institution of female agricultural cooperatives was founded in the 1950s. The Department of Rural Home Economics, established by the Ministry of Agriculture, took over the training on home economics for farmers and rural households. The target set by the Ministry of Agriculture was to support the economy of the farming household, achieve additional income and increase the social status of rural women. The first women’s agricultural cooperative was founded in 1957, Sarakina Grevena. At that time, approximately 10 agricultural cooperatives were founded but none of them were economically successful [8] .

From the mid 1980’s onwards, alongside the strengthening of gender equality, a second policy axis was developed. This axis promoted multiple-employment of farmers of both genders in the agricultural sector. Multi- employment combined the activities of agricultural production with one or more other paid activities within or outside the agricultural sector. Combining these two policy axes, institutional bodies in Greece supported the establishment of many female agricultural cooperatives throughout the country. At that time there were many initiatives to enhance the establishment and operation of rural women’s cooperatives such as the Regulations 797/85, 2328/92, the European Community’s Initiative LEADER, the programme NOW—New Opportunities for Women. It was then thought that female agricultural cooperatives were acting as a good tool for mobilising farmers in creating cooperative businesses. In their turn, those businesses would utilise their informal household knowledge [8] .

At that time, female farmers’ participation in women’s cooperatives was mainly reflected in a change in woman’s status within the society. The first Rural Women’s cooperative was founded in 1984 in Petra on Lesvos Island and it was supported from the General Secretariat for Gender Equality. The main reason for this was to achieve empowerment through economic self-reliance that would allow them to participate in the cooperative. During 1985, a number cooperatives were established; the cooperative of Ampelakia in Thessaly region, of Mastichocoria in Chios, of Arachova in Viotia, the one of Agios Germanos in the region of Prespes and the Maroneia in Rodopi [9] [10] .

Most Rural Women’s Cooperatives were founded under 2810/2000 law of “Rural Cooperative Organizations” [11] . The law focused on cooperatives towards an enterprising direction. As only seven individuals were required for forming a Cooperative, it was beneficial for rural women. Thus, it could be based in the wider area of its members’ residence and rural women could unify their efforts to choose their production activity.

In 2011, Government passed a new institutional framework for agricultural cooperatives [12] . The new law states that for the establishment of cooperative at least 20 members are required. Moreover, economic criteria for sustainability of cooperatives (e.g., minimum capital cooperative 30.000 Euros) had been defined and mergers between small cooperatives were promoted. Following consultation, the government excluded those female agricultural cooperatives already operating by economic sustainability criteria and the minimum required number of members.

Women’s agricultural cooperatives were businesses in traditional sectors of female employment in the tertiary sector (commerce, services) and addressed to end consumers. Many researchers argue that the policy followed in relation to gender equality in rural areas and women’s entrepreneurship maintains the distinction of gender roles and contributes to the removal of women from family agriculture. In this process, the man strengthens his position within agriculture and farming remains a profession for males [13] - [16] . The rural women, members of rural women’s cooperatives also risk losing their identity as farmers, by national laws relating to income derived from the female agricultural cooperatives. If a cooperative is achieving good economic progress and the income of its members exceeds the agricultural income, then the farmers are treated as self-employed and their income from the partnership is taxed as non-agricultural and where higher agricultural incomes they lose access to grants and participation in agricultural programs, i.e. losing the identity of rural women [17] [18] .

2.2. Theoretical Background about Entrepreneurial Characteristics of Rural Women Cooperatives

In rural areas, rates of necessity-driven entrepreneurship are even larger than the corresponding rates in urban areas and higher in female than in male in all classes of income in developed countries, with higher rates in small and middle-income classes [19] [20] .

A problem that has become more acute in rural areas of Greece (as well as in urban areas) associated with the economic crisis and austerity measures. The increase in poverty is a reality and according to the statistics of the Hellenic Statistical Authority, 2010 and 2011 the risk of poverty is greater in female than in male population [21] [22] .

Rural women decide to enter the job market and entrepreneurship between the ages of 35 and 45. At these ages, professional life coexists and coincides better with family life, due to reduced family obligation, such as children care because by this time their children are in the age of ten or older [20] [23] [24] . They decide to become actively involved in business in order to have equal participation in the decision making of the rural household and in order to provide themselves with additional income. They claim their independence and socialize outside their residence [25] - [28] .

A study conducted within the framework of the evaluation of programs based on Council Regulation (EC) No. 950/97 [29] showed that the establishment of women’s agricultural cooperatives actually improved the economic and social status of women farmers-members. The economic improvement was estimated by the farmers-mem- bers themselves as small to moderate in most cases, while the social improvement was assessed as very important and connected with the social prestige of the members and the vindication brought a success [30] .

Rural women, members of women’s agricultural cooperatives are lacking of formal education and training in the agricultural sector, as well as on the use of new technologies and the internet. The lack of farmers in terms of formal education and vocational training occurs nationwide and according to the Ministry of Rural Development and Food, 69.5% of men and women farmers are graduates of primary school, 14.3% have completed some primary classes or have no education, 15% are graduates of secondary education or the three grades of high school and only 1.2% are graduates of universities and technical colleges [1] .

The members of women’s agricultural cooperatives do not face partnering in a cooperative with business criteria. They are particularly reluctant to risk-taking and show a lack of implementing innovations [8] [25] [31] . The lack of the element of risk taking by farmers is reflected in the profile of women’s agricultural cooperatives. In Papageorgiou et al. [30] , the 50 agricultural cooperatives by female participants stated that when establishing the cooperative share was about 147€, income generally was very low and the surpluses were ranging from minimal to negative.

Studies have shown that most women’s agricultural cooperatives operate as small “closed” family businesses. Few of them have permanent staff, account books were kept by an external accountant and do not employ professional staff for organization, management and marketing purposes. Brochures, local media and participation in local and national exhibitions were the means of advertising they used. Although advertised in official websites, only few of them used electronic commerce [8] [25] .

Other studies have shown that women’s agricultural cooperatives in Greece suffer from organisation and administration. There is a reduction in the number of members that existed at the time of their establishment, there is no age renewal and replacement of members that make up the Board of Directors and the lack of administrative and organizational experience of the Directors and their chairmen often lead to problems sharing at work and clashes between members of cooperatives [25] . Moreover, several cooperatives fail to provide an adequate income for their members and do not provide a significant alternative employment [32] [33] .

Nevertheless, there are women’s agricultural cooperatives (few in number) as examples of good practices. In these cooperatives, a core group of women younger than the other members, are dynamic and have business skills such as initiative, risk-taking, the ability of cooperation and networking and the willingness to implement innovations [8] .

3. Material and Sample

3.1. Material

In March of 2013, the National Rural Network of Greece (NRN) established a committee for studying the needs, problems and difficulties faced by rural women. The purpose of the committee was the integration of gender’s mainstreaming into the new rural developing programme 2014-2020. Participants as members in the Greek National Rural Network are Chambers, Research Institutes, Environmental Organizations, LAGs etc. Members of the Network are also agencies of the Ministry for Agricultural Development and Food and the Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climatic Change, which are responsible of the management and implementation of some measures of the Rural Development Program (RDP).

The two researchers were members of the committee and they decide to conduct a nationwide survey on business characteristics of rural women’s cooperatives in Greece. The purpose of this study was to identify the needs of members of women’s cooperatives in rural education and financial support, in order to join relative actions and development projects in rural areas in the new programming period 2014-2020.

At the beginning of the research, the two researchers found out that up to now, accurate data on the number of female agricultural cooperatives do not exist. In 2012, the Ministry of Rural Development and Food created the National Register of rural cooperatives, in which all national cooperative organisations in the country that met the requirements of the new law passed by the Government in 2011 should be entered. The registration of cooperatives in the Register is not finished yet and therefore the exact number of female agricultural cooperatives in Greece is not known accurately. However, an informal list of the Ministry of Agriculture shows that around 140 female agricultural cooperatives are currently operating, of which 125 cooperatives are “established” companies and 15 are “new businesses”, i.e. they have established from 2009 onwards. The criteria between “established” and “new” cooperatives based on the definition of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor which has determined that when an enterprise has operated for more than 42 months by paying wages and generating profits, it is more likely to survive and develop. These enterprises can be categorized as “established” [34] .

3.2. Sample and Statistical Analysis

The survey ran from March to July 2013. The sampling method can be classified as a non probability at convenience sampling method. The proportion of cooperatives that corresponded to the questionnaire is considered quite satisfactory from the literature [35] .

Due to the large geographical spread of the sampling units and the absence of an accurate National record of rural cooperatives, the method of data collection questionnaire with closed-ended questions was chosen. The data collection process was the completion of a questionnaire by the chairwoman of each cooperative. The design of the questionnaire allowed gathering data of nominal, scale and ratio type. The questionnaire included questions about:

1) The organization and function of the Cooperatives from the date of their foundation up today such as Legislative Framework, co-operative shares, funded by national and/or European programs, distribution of products, certified products, use of new organization and management practices (e.g., quality control systems, organization and management of e-programs and web sales, association and collaborations with other businesses, ways of publicity).

2) Demographic characteristics of the members such as the number of members from the date of their establishment up today, the ages of members today, members’ educational level, members’ knowledge and use of personal computers and the Internet, participation in continuing education and training.

3) Self-assessment of participation of the chair women (positive or negative implications on their family income, and on their family and personal lives).

4) Educational and financial needs.

The two research questions refer to:

a) Investigate any difference concerning the aforementioned factors between cooperatives before and after 2009 (“established” and “new”).

b) The evaluation of the economic progress of Cooperatives that exploit new trends (ISO/HACCP/e-com- merce).

Statistical analysis of the data included descriptive and inferential methods. In descriptive statistics and for continuous variables measures of central tendency (median, mean, maximum and minimum) and dispersion (inter-quartile range and standard deviation) were calculated. In order to decide which statistical indicators will be calculated, Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test has been employed to determine whether the reported observations follow a normal distribution. Analysis showed that variables regarding the number of members and the cooperative shares did not follow a normal distribution (K-S, p < 0.05), while aggregated data on members’ age, level of education and skills can be considered to follow a normal distribution. For the first category of variables, median and interquartile range was calculated, while for the second mean value and the standard deviation. For the categorical variables the absolute and relative (%) frequencies of the answers were presented.

In bivariate analysis and to examine if any dependency between two qualitative variables exists, χ2 test for independence has been used. From the tests no statistically significant dependence between the two qualitative variables was revealed. Also to test any statistically significant difference in cooperative shares and the number of members (at the beginning of the establishment of cooperatives and present), nonparametric Wilcoxon test (for paired observations) has been utilized.

Regarding the power of statistical tests and the trying to minimize the type II error (accepting the null hypothesis while it is false) for the sample of 49 sample units and for two-tailed statistical tests in repeated measurements, the power of the test, is of the order of 79%, which is satisfactory, with the literature accepting as a lower rate 80% [36] [37] . So the possibility in statistical tests performed for type II error is of the order of 20%. Conclusively, the sample of 49 cooperatives can be considered to be safe enough to draw general conclusions, minimizing type I & II statistical error within the acceptable scientific limits according of international literature. The significance level for rejecting the null hypothesis for all tests, was 5%. All calculations were performed with the statistical software SPSS ver. 17, while for the power of the tests GPower ver. 3.

4. Results

The results showed that the organizational and business structure of female agricultural cooperatives does not differ:

· Among the “new” and “established” cooperatives.

· Between cooperatives that exploit the new business trends (ISO, HACCP, e-commerce, etc.) and those that do not exploit.

· Among the various prefectures of Greece.

The research indicated the follow main points:

4.1. Small Amount of Cooperatives Shares

Although there is a statistically significant increase of the average trend of cooperative shares from 226€ to 580€ (260% increase), (p < 0.001 Wilcoxon test), the amount of cooperative shares (Median 580€) does not meet the minimum cooperative fund of 30.000 Euros required by Article 8 of Law 4015/2011. Median of total Fund is 5.800 Euros and from 49 cooperatives only 6 (12.2%) have the conditions established by the Law. Note that women Rural Cooperatives established until the creation of Law 4015/2011 have been excluded from the specified minimum cooperative capital (Graph 1).

The most of Rural Women’s Cooperatives were founded in 2000 and after, under the national law 2810/2000. The 63.3% of the cooperatives was financially supported during its foundation. From these particular cooperatives, 58.1% of the cooperatives were financially supported by a funding source and 22.6% was supported by two simultaneous sources. Most cooperatives have been supported by government programs for unemployed aimed at entrepreneurship (58.1%), while other cooperatives have been supported by other initiatives to enhance the establishment and operation of women’s agricultural cooperatives such as the Community Initiative LEADER, EQUAL, etc.

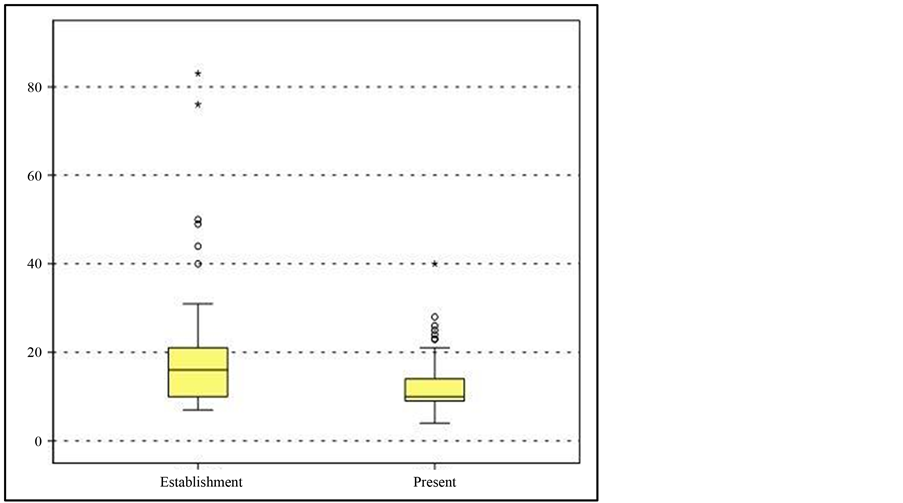

Graph 1. Boxplot of cooperative share in € between establishment period and present.

4.2. Lack of Cooperative Culture

Two out of three female agricultural cooperatives lack collaborative culture and networking. In addition, they show reluctance to participate in professional and trade organizations.

More specifically, only 38.8% responded that cooperatives have cooperation with other women’s cooperatives mainly on supply of raw materials (47.4%), joint service (36.8%), information exchange (31.6%), joint selling products (15.8%) and joint marketing of products (5.3%). In addition, a great percentage (71.4%) of the Cooperatives does not participate in a higher level Cooperative organization while 40.8% of the Cooperatives participate in a professional, non Cooperative organization.

When asked if the cooperative is “open” to new members, 51% said that they wish the entry of new members under conditions and 36.7% said that they wish the entry of new members without conditions, while a rate of 12.2% stated that they do not wish the entry of any new members in the cooperative.

4.3. The Number of Members is Declining and Aged

During the establishment of the 49 rural women’s cooperatives, 983 members were involved, while the period of research, 642 members remained. The decrease in membership is 34.5% and the decline of the median indicator from 16 to 10 people per cooperative is statistically significant (p < 0.001, Wilcoxon test) (Table 1 and Graph 2).

As far as age distribution is concerned, 50.8% of the members were between 41 - 55 years old and 25.6% were between 56 - 65 years old. A very small percentage of the members (1.6%) were between 18 - 25 years old and 18.8% of the members were between 26 - 40 years old (Table 2).

4.4. Low Educational Background and Lack of Skills of Membership

A great percentage of the members (43.4%) were graduates of elementary school or had attended a few classes and 17.7% had attended the first three years of high school. A percentage of 31.3% had education that reached the final classes of high school, while 7.6% had graduated from a higher education institute.

Out of the 49 cooperatives, only 17 of them had university graduates from higher education or technological institutes, while all 49 cooperatives had members that attended some classes of elementary school or were graduates (Table 3).

A percentage of 19.1% of the members stated that they could use a PC and 16.9% stated that they could use internet. Only 13% of the members could communicate the English language. Most of female agricultural cooperatives (75.5%) took part in the survey corresponded that they engaged with one productive activity, while 24.5% with more than one productive activity.

Graph 2. Boxplot of members of the cooperative between the period of the establishment and present.

![]()

Table 1. Statistical indicators of change in the number of members (N = 49).

![]()

Table 2. Statistical indicators of members by age group.

![]()

Table 3. Statistical indicators of the number of members per educational level.

4.5. Lack of Modern Business Methods

Cooperatives, in percentage of 85.7% mainly produce traditional food. Other parallel or individual productive activities of cooperatives are the production of traditional handicraft products, agro-tourism (farm houses) and the operation of food services.

They do not seem to have used and/or have not fully used the financial programs in order to improve their laboratories for the certification of the production process and the use of new technologies for the operation and promotion of their products (ISO, HACCP, e-commerce).

A 75.5% of the Cooperatives don’t utilize management software. Although 57.1% of the Cooperatives appeared in web pages, only eight of 49 Cooperatives (16.3%) used the e-shop through their page.

A 16.3% of the Cooperatives had certified the productive procedures with quality control systems (e.g., Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points). Another 8.2% of them declared that their facilities satisfied the certification requirements of the productive procedures with quality control systems, but they had not taken any actions to implement the systems. Only 4.1% of the Cooperatives had certified their products (e.g., as organic products and/or certified traditional goods).

Three out of four Cooperatives (73.5%) are using exhibitions for their marketing efforts, while a percentage of 55.1% is also media (press, radio, TV) for promoting their products.

The products of the Cooperatives were distributed mainly in the local market and within the Prefecture of their area (65.3%) and secondarily in the wider Greek market. Only a percentage of 16.3% of Cooperatives distributed their products in European countries.

4.6. Positive Self-Assessment of Participation in Cooperative

The female farmers assess the long-term participation in cooperative positive. More specifically, 79% of the chair women said that their participation in the cooperative helped in the long term in the increase of the monthly family income, although 77.8% assessed that the economic gains from the cooperative were less than their expectations. At the same time, a 21% responded that their participation in the cooperative did not add additional monthly income. In the present economic situation in Greece, two out of three presidents (63.2%) responded that they are satisfied with the financial performance of the cooperative.

A 63.3% of the chair women said that their participation in the cooperative only positively affected their family life and 30.6% of chair women felt that participation in cooperative had positive and negative effects in family life. A percentage of 6.1% replied that the participation in the cooperative only negatively affected their family life.

Apart from the increase in their family income, 63% of the chair women believe that the participation in the cooperative helped them to improve their social status and approximately 71.7% believe that they learned to better evaluate their free time. As far as the negative consequences of the participation in cooperative are concerned, presidents believe that they have less time to take care of their families and themselves (38.9%).

In the present economic climate, however, two out of three of chair women (63.2%) evaluate the financial performance of the cooperative negative.

4.7. Areas of Training and Sectors of Financial Needs

In relation with the new 2014-2020 period, 60.4% of the sample responded that they would like specific programs supporting women’s economic cooperatives, and at the same time training programs for the members. The sectors that they need financial support are for the marketing of their products (87.5%), modernization their laboratories (72.9%), establishment of quality certification systems (68.8%) and the networking with similar feminine rural cooperatives (39.6%).

As far as the training modules is concerned, they are focused mainly on marketing issues of their products (80.9%), followed by training to improve the standardization and packaging of their products, training for the use of new technologies and internet, on production processes and product certification and training for better organization and management of cooperatives (Table 4).

5. Discussion

The rural women’s cooperatives in Greece have contributed to long-term improvement of rural family income

![]()

Table 4. Educational needs (N = 47).

and social status of female farmers.

This research has highlighted once again the established introverted organizational and business structure of female agricultural cooperatives in Greece, which has also emerged more times from the literature.

Moreover, the research highlighted a contradiction between their claims in relation to the actions of the upcoming Rural Development Programme 2014-2020 and their entrepreneurship: The two previous programming periods of the European Union (2000-2006 and 2007-2013), there were many actions for the financial support and training of rural women’s cooperatives for the modernization of their laboratories, certification of the production process and their products, the use of new technologies to improve the operation of cooperatives and the promotion and sale of products (ISO, HACCP, e-commerce). Nevertheless, the chair women of women’s agricultural cooperatives appear to ask again for financial and educational support for the same modules, while they should have already used all the previous programs and have moved the business forward. One question that arises is why they did not take advantage of all the opportunities provided by the financial programs and educational support of the EU during the two previous programming periods and slowly progressed or not progressed at all in modern forms of organization and administration and modern forms of certification, standardization, promotion and sale of their products. Another question is if rural women who act in the rural women’s cooperatives of Greece have the capacity and the skills to adopt an enterprise model of modern business behaviour, that will also maintain the traditional production procedure and the cultural character of each region of Greece.

It is obvious that an incentive for age renewal in female agricultural cooperatives should be given and legislation for voluntary and/or forced combinations and/or networking of female agricultural cooperatives either at the level of law or in District level. Also in the new programming period 2014-2020 Rural Development, there should be incentive measures and incentives for networking with businesses that are complementary to the object of female agricultural cooperatives (e.g. mass tourism enterprises).

To enable the farmer businesswoman to correspond to the needs of the modern market conditions, she should have high educational level and training. The modern farmer businesswoman is required to be able to cope with the written questionnaires and standardized forms of signal quality HACCP and ISO required in the manufacturing process, marketing and in agro-tourism respectively, or to network her business with other similar businesses, to know basic English, i.e. to have increased skills and knowledge.

Women that are members of women’s agricultural cooperatives should be able to adopt a modern business behaviour (e.g., introduction of quality systems, New Technologies in the organization and management of cooperatives, etc.) while also incorporating in the production process their cultural and traditional character in order not to harm the tradition and specificity of products and services.

The training members of women’s agricultural cooperatives can be targeted to groups of members, depending on their age and level of education (formal and non-formal education). The training modules can be the topics listed in the survey (e.g., business administration, e-commerce, new technologies and internet, English language), but also in other disciplines (e.g., marketing, stock optimization, etc). The training provided to rural women, either potential or existing business women, should focus mainly on the procedures of finding, evaluating, and developing enterprise opportunities.

Finally, the economic incentives for the modernization of their laboratories must continue, the production of organic products and products of geographical indication, the implementation of quality systems, the introduction into the production process of “green” New Technologies environmentally friendly (e.g., use renewable energy) and the expansion of their productive activities and services.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, the research identified that the entrepreneurship model of rural women’s cooperatives in Greece contains problematic areas. Rural women should change their attitude and their perception on issues of entrepreneurship and they should adopt another way of entrepreneurial behaviour that would contain modern business methods.