Prevalence of Vaginal Candidiasis and Determination of the Occurrence of Candida Species in Pregnant Women Attending the Antenatal Clinic of Thika District Hospital, Kenya ()

1. Introduction

Vaginal candidiasis affects approximately 75% of women of child-bearing age [1]. Factors that predispose women to vaginal candidiasis include hormonal fluctuation, i.e., during pregnancy, luteal phase of menstrual cycle, antibiotic uses and use of oral contraceptives [2]. Another 5% - 10% of seemingly healthy women suffer recurrent vaginal candidiasis without any predisposing factors [3]. It is much more common in pregnant women than in healthy women. Moreover, a large proportion of women with chronic recurrent candidiasis first present with the infection during pregnancy [3].

In pregnant women, vaginal candidiasis has been related to emotional stress and suppression of immune system which step up the risk of Candida species overgrowth and become pathogenic [5]. Other risk factors are associated with the eating habits of pregnant women of sugar rich containing food. The sugar increase ever more the threat of yeast infections powered by these sugary environments. Pregnancy induced hormonal modifications, altered the vaginal context and made Candida more likely to grow beyond acceptable boundaries [6]. Candida is the agent most frequently implicated in the invasive vaginal candidiasis. The most common Candida species causing vaginal candidiasis is primarily Candida albicans followed by Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis and Candida parapsilosis [3].

In the recent years, the number of serious opportunistic yeast infections, particularly in immunocompromised patients, has dramatically increased [13]. Among them, Candida species accounts for a large number of serious opportunitistic yeasts in pregnant women. Previous studies done in Kenya on the isolation and identification of Candida species used different clinical samples from different study populations. These included HIV/AIDS patients and children with acute respiratory infections where Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida krusei among others were isolated and identified [14]. However, no study has been done on pregnant women. Therefore, the present study is the first study to be carried out in Kenya.

In developing countries, there is scanty data on vaginal candidiasis in pregnant women and the distribution of the vaginal Candida species [24]. In Kenya, there are no data that document the prevalence of vaginal candidiasis in pregnant women. The present study therefore intends to determine the prevalence of vaginal candidiasis among pregnant women, identify the causative vaginal Candida species and their distribution in pregnant women.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A cross sectional study among pregnant women with symptoms of vaginal candidiasis attending the antenatal clinic of Thika District Hospital was adopted.

2.2. Sampling Technique

Purposive sampling technique was used among the pregnant women with symptoms of vaginal candidiasis attending the antenatal clinic of Thika District Hospital.

2.3. Study Approval, Ethical Consideration and Informed Consent

The study was approved by Kenyatta University and Thika District Hospital. Ethical consideration was obtained from the Hospital Ethical Review committee. The consent form was read and explained to the pregnant women. After understanding and accepting for participation, they signed it.

2.4. Laboratory Procedure

2.4.1. Sample Collection

For the purposes of the study vaginal swabs were collected from pregnant women with symptoms of vaginal candidiasis who attended the antenatal clinic of Thika District Hospital between the months of June and August, 2010. The pregnant women were deemed symptomatic if they presented with itching, difficult in walking, dysuria and presence of thick adherent plaques on the vulval, vaginal or cervical epithelium. Samples collected were tested for vaginal Candida species. The women were stratified into four groups according to their ages as follows: 15 - 25, 26 - 35, 36 - 45, and over 46 years. They were also stratified according to the trimester of the pregnancy as first, second and third trimester.

2.4.2. Gram Stain

The test was carried out essentially according to the procedure of Chander et al. (2002) [7]. Smears were made from the vaginal swab and stained using the gram staining procedure. Gram stained smears were used to examine the presence of gram positive budding yeast cells with pseudohyphae. Specimen was considered as acceptable when 25 or more polymorphonuclear leukocytes were seen per low power field (100×) with few (less than 10) squamous epithelial cells [7].

2.4.3. Culture Procedure

Samples were cultured on Saborauds dextrose agar (SDA) containing two percent chloramphenicol. Inoculated plates were incubated at 37˚C and examined after 48 hrs for cream colored pastry colonies and budding yeast cells suggestive of Candida species. Isolates from SDA were inoculated on CHROMagar (France) using an inoculating needle and incubated at 37˚C for 72 hours to ensure detection of mixed cultures by color changes. The method is based on the differential release of chromogenic breakdown products from various substrates by Candida species following differential exoenzyme activity [8]. This test was used for presumptive identification of C. albicans, C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis.

2.4.4. Chlamydospores Formation Test

All Candida isolates were tested for the production of chlamydospores in corn meal agar with Tween 80 [8]. The isolates were i noculated in cornmeal agar. The test involved streaking and stabbing the media with a 48 hour old yeast colony and, covered with sterile cover slip and incubated at 25˚C for 72 hours. Chlamydospore production was examined after staining with lactophenol cotton blue (Dalmau morphology method) [8]. The isolates were categorized as chlamydospore positive or negative. The test was used as a presumptive confirmatory test for the identification of Candida albicans.

2.4.5. Germ Tube Test

This method was used as a presumptive test for identifycation of Candida albicans. Procedure of Baker et al. 1967 [8] was used in carrying out the test. A single colony of the test yeast cells from a pure culture was inoculated in human serum and incubated at 37˚C for 2 - 4 hours. A drop of the incubated serum was placed on a microscope slide and covered with a cover slip. The wet mounts were examined under the microscope for the presence of germ tube using the 40× objective (Dalmau morphology method) [8]. The isolates were classified as either germ tube positive or germ tube negative.

2.4.6. Sugar Assimilation Test

The test was carried out essentially according to the procedure of Lodder et al. 1970 [9]. The assessment of the ability of yeast to utilize carbohydrates was based on the use of carbohydrate-free yeast nitrogen base agar [9]. Observation for the presence of growth around carbohydrate impregnated filter paper discs was done after incubation for 18 hours at 30˚C. Carbohydrates used were glucose, galactose, lactose, maltose, sucrose, raffinose, trehalose and cellobiose. Presence of growth in the medium indicated the ability of the isolate to assimilate a sugar [9]. The Candida species were identified using the sugar assimilation patterns for individual species as shown by Lodder et al. 1970 [9].

2.5. Data Analysis

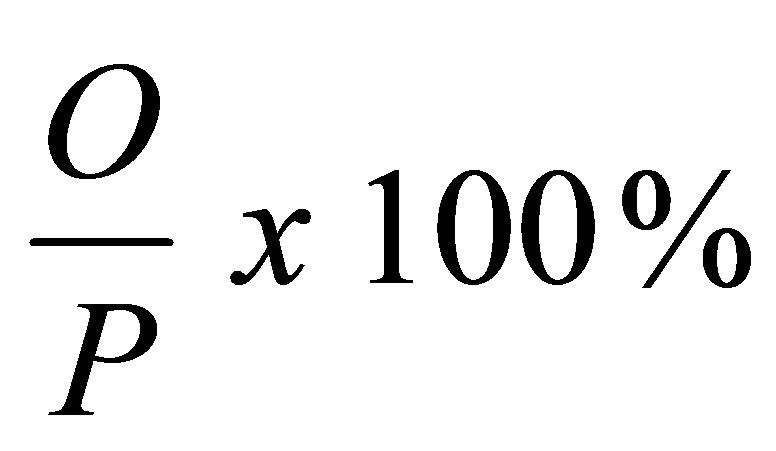

All collected data was introduced into Microsoft excel data sheet. Prevalence of vaginal candidiasis was calculated using the formula of Le and Boen et al. 1995 [25]. The relationship between the occurrences of vaginal Candida species in the various age groups of the pregnant women was calculated using Person moment correlation and Chi-square tests. All the statistical analysis was done using MINITAB and SPSS version 13.0 computer package.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Vaginal Candidiasis in Pregnant Women Attending the Antenatal Clinic of Thika District Hospital

One hundred and four (104) of pregnant women with symptoms of vaginal candidiasis visiting the antenatal clinic of Thika District Hospital participated in this study. Ninety four, 94(90.38%) of the pregnant women tested positive and 10(9.62%) tested negative for vaginal candidiasis infection in the laboratory as shown in Table 1.

The number of positive pregnant women in relation to the total population involved in the study was calculated to give the percentage prevalence of vaginal candidiasis among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic of Thika District Hospital.

Table 1. Prevalence of vaginal candidiasis in pregnant women attending the antenatal clinic of Thika District Hospital.

Using the formula

where: O = The number of individuals with the disease.

P = Total number of individuals in the population involved in the study at the study period.

Percentage prevalence = 94/220 × 100% = 42.7%.

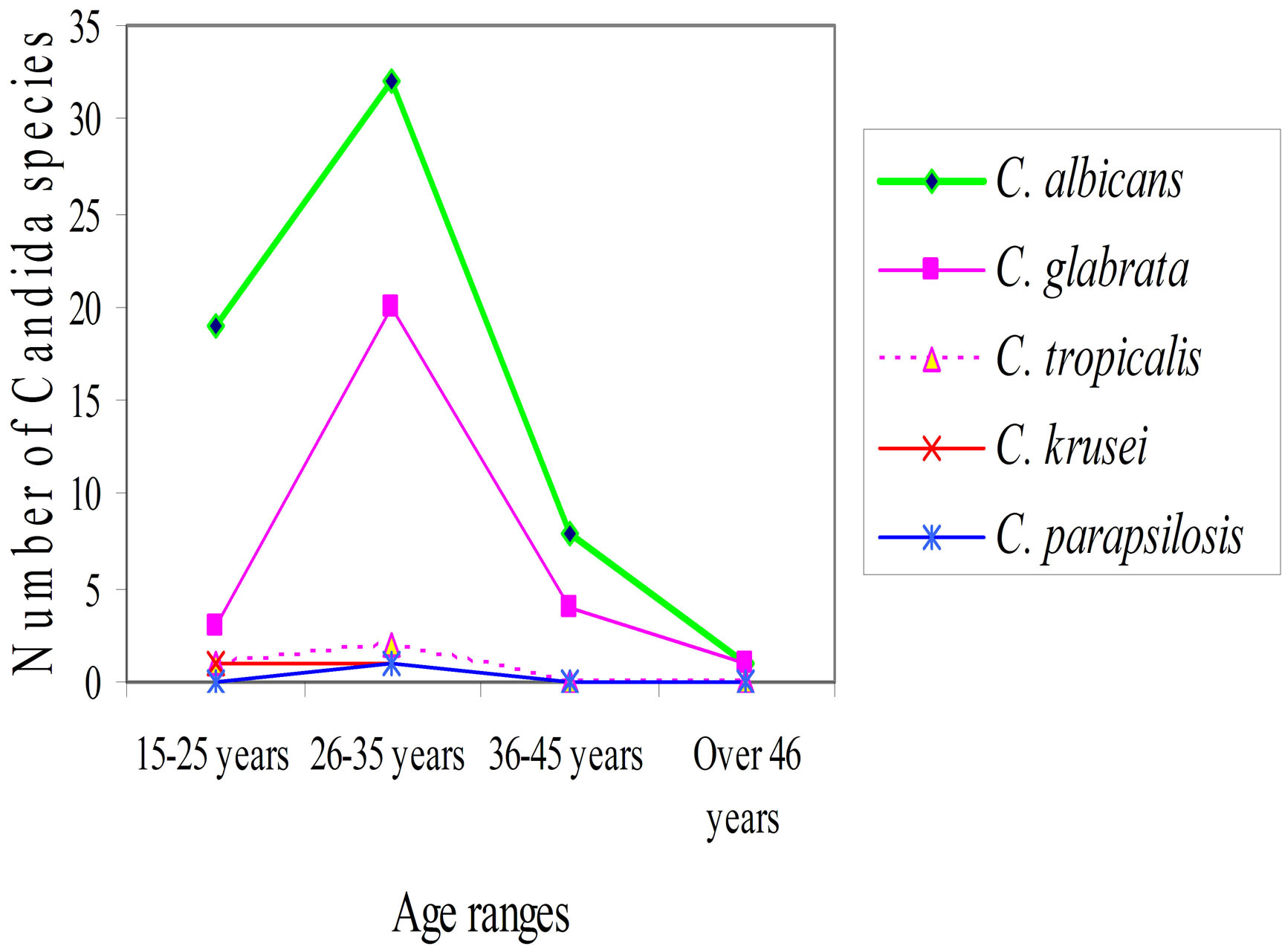

The percentage distribution of vaginal candidiasis among the different age groups were as follows; 56(60%) of the women were 26 - 35 years of age, 24(26%) were in the ages of 15 - 25 years and 12(12%) were 36 - 45 years while the least number of patients 2(2%) were over 46 years of age (Figure 1). The study noted that frequency of vaginal candidiasis significantly increased with the ages in pregnant women below 35 years (r = 1.00, P = 0.00, P < 0.05). However, in pregnant women above 35 years of age, there was a significant decrease in frequency of vaginal candidiasis (r = −1.00, P = 0.00, P < 0.05).

3.2. The Distribution in Percentage of Vaginal Candidiasis According to the Trimester of the Pregnancy

The results showed that the 3rd trimester had the highest number of patients 64(68.09%), followed by 2nd trimester with 20(21.28%). The 1st trimester had the least number of patients 10(10.63%) as shown in Figure 2. The occurrence of vaginal candidiasis infection in pregnant women was significantly different in the three trimesters (F = 103.17, df = 2, p = 0.002).

3.3. Isolation and Identification of Vaginal Candida Species

Among the 94 pregnant women with vaginal candidiasis, five (5) Candida species were isolated and identified. These were Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida krusei and Candida paraps Zilosis.

The results for the percentage occurrence of vaginal Candida species in pregnant women were as shown in Figure 3. Candida albicans 60(63.83%), Candida glabrata 28(29.79%), Candida tropicalis 3(3.19%), Candida krusei 2(2.13%) and Candida parapsilosis 1(1.06%).

Figure 1. The percentage distribution of vaginal candidiasis within different age ranges of the pregnant women.

Figure 2. The distribution in percentage of vaginal candidiasis according to the trimester of the pregnancy.

Figure 3. The occurrence of vaginal Candida species in pregnant women.

3.3.1. Occurrence of Vaginal Candida Species

To determine the occurrence of the different vaginal Candida species isolated, One-way ANOVA was used to analyze the data. The results showed that there was a significant difference in the occurrence of the Candida species causing vaginal candidiasis in pregnant women (F = 616.62, df = 4, P = 0.000). This result incriminated Candida albicans as the most common vaginal Candida species causing vaginal candidiasis among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic of Thika District Hospital as shown in Figure 3 above.

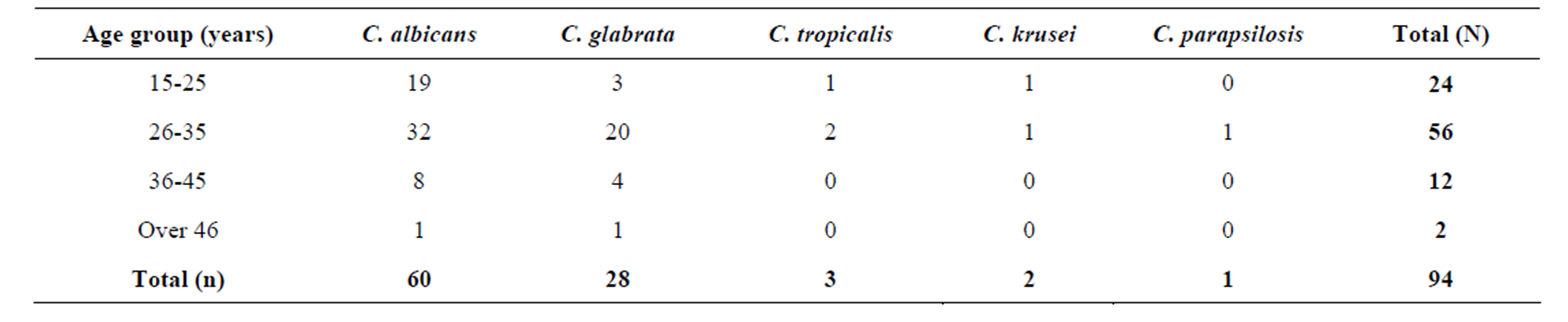

3.3.2. The Distribution of Vaginal Candida Species within Different age Groups of the Pregnant Women

The results showed that most of the vaginal Candida species were isolated from the pregnant women at the age brackets of 26 - 35 years with a total of 56(60%) isolates. The youngest group of 15 - 25 years followed with 24(26%) isolates. The age group of 36 - 45 years had 12(12%) isolates and the age group of over 46 years had the least number of isolates with 2(2%) as shown in Table 2.

Candida albicans and Candida glabrata were the most isolated vaginal Candida species in the age bracket 26 - 35 years. These results incriminated Candida albicans as the most common Candida species causing vaginal candidiasis in all the age brackets of these pregnant women. It was observed that all the vaginal Candida species were isolated in the age group 26 - 35 years. The data showed that the occurrence of vaginal Candida species increased with age in pregnant women below 35 years (r = 0.351, P = 0.394). However, in those women above 35 years of age, there was a decrease in occurrence of vaginal Candida species (r = −0.496, P = 0.060) as shown in Figure 4.

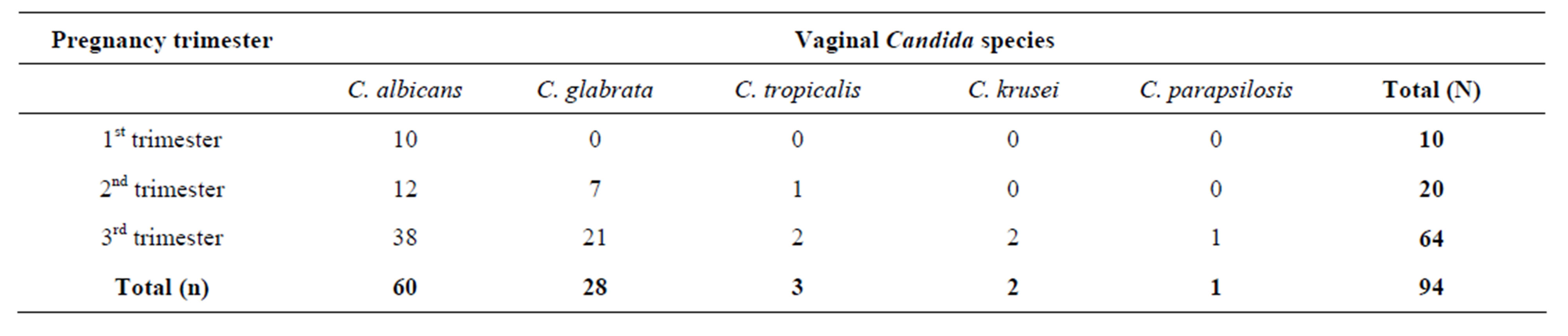

3.3.3. The Distribution of Vaginal Candida Species According to the Trimester of Pregnancy.

The results showed that the 3rd trimester had the highest number of vaginal Candida species isolated with 64(68.09%), followed by 2nd trimester 20(21.28%). The 1st trimester had the least number of species with 10(10.63%) as shown in Table 3.

Figure 4. Vaginal Candida species isolated within different age groups of the pregnant women.

Table 2. The distribution of vaginal Candida species within different age groups of the pregnant women.

Table 3. Distribution of vaginal Candida species according to the trimesters of pregnancy.

The 3rd trimester had all the five (5) vaginal Candida species isolated. Candida albicans was the only species isolated in all the three (3) trimesters of pregnancy. It had the highest occurrence rate than all the other vaginal Candida species especially in the 3rd trimester of pregnancy. Therefore, it was incriminated as the most common vaginal Candida species causing vaginal candidiasis in all the 3 trimesters of pregnancy. Candida glabrata was isolated in 2nd and 3rd but not in the 1st trimester. It was the second most common species isolated in the 3rd trimester. Candida tropicalis was isolated in 2nd and 3rd but not in the 1st trimester. Candida krusei and Candida parapsilosis were very few and only isolated in the 3rd trimester as shown in Table 3 above.

4. Discussion

4.1. Patients

The study was done in Thika District Hospital. Pregnant women aged fifteen years and above who visited the antenatal clinic of the Hospital between the months of June and August, 2010 with symptoms of vaginal candidiasis were enrolled in this study. Most of these women were from the nearby Thika slums and were mainly single mothers. Eighty percent (80%) of these women had a history of using contraceptives before they got pregnant. Seventy percent (70%) of the women had been using over the counters antibiotics and antifungal agents for treatment of the infection.

4.2. Prevalence of Vaginal Candidiasis and Occurrence of Candida Species

In the present study, a prevalence of 42.7% of vaginal candidiasis in pregnant women attending the antenatal clinic of Thika District Hospital was reported. This was probably due to suppression of the immune system due to the pregnancy as it is among the contributing factors of vaginal candidiasis [4]. Use of contraceptives by the women before they got pregnant and the misuse of antimicrobial agents (antibiotics and antifungal agents) leads to the destruction of normal flora (bacteria) resulting to reduction of vaginal immunity could have also contributed to the increase of the prevalence of the infection. This is in agreement with other findings by Feyi [26] in Tanzania where he reported a prevalence of 42.9% of the infection in pregnant women.

A higher frequency of vaginal candidiasis within different age ranges of the pregnant women was observed within the age ranges 26 - 35 years (60%). The infection was at a higher frequency in this age group than the other age groups due to the fact that women in this age group are likely to use drugs indiscriminately and use contraceptives to prevent pregnancy. These behaviors could have contributed to the high frequency of the infection in this age group. The observation in this study is consistent with reports of other workers [10-12]. Sehgal et al. [10] reported a 54% incidence rate within age bracket 20 - 30 years in Northern Nigeria. Fifty five percent (55%) incidence rate was reported within age group 26 - 35 years in Benin City by Okungbowa et al. [11] while Akortha et al. [12] reported 57% within age bracket 26 - 35 in Benin City, Edo state in Nigeria. These reports documented that the age group is vulnerable probably due to sexual promiscuity, drug abuse and use of contraceptives.

A slightly lower rate of vaginal candidiasis infection in the pregnant women was observed in this study within the age ranges 15 - 25 years (26%). This age group was second in prevalence of infection from age ranges 26 - 35 years in this study. The age group contains women who are younger and are sexually active. They also have the habit of using contraceptives especially the emergency pills to prevent pregnancy. They also misuse drugs especially antibiotics for treatment of such infections. The frequency was also high within this age group in this study because of sexual promiscuity and the use of contraceptives that are predisposing factors of vaginal candidiasis. The misuse of drugs results to drug resistance especially to the common antifungal agents used for the treatment of vaginal candidiasis. This might have also contributed to the high frequency of the infection in this age group.

The results are in line with other studies [11,12] where they reported that the age group was second in prevalence of vaginal candidiasis from age ranges 26 - 35 years with prevalence rates of 24% and 30% respectively. He reported that women in this age group were becoming sexually active and have low vaginal defense mechanisms against Candida species [20]. The present study noted that frequency of vaginal candidiasis significantly increased with the ages in pregnant women below 35 years (r = 1.00, P = 0.00, P < 0.05). However, in pregnant women above 35 years of age, there was a signifycant decrease in frequency of vaginal candidiasis (r = - 1.00, P = 0.00, P < 0.05).

A lower rate of prevalence of the infection in pregnant women was reported within the age ranges 36 - 45 years and over 46 years age group with prevalence rates of 12% and 2% respectively. Women in the age group 36 - 45 are nearing their menopause age and are becoming less sexually active. This may be the reason why vaginal candidiasis was recorded at a low prevalent rate in this age group. Women in the age group of over 46 years have reached their menopause age and are not sexually active. They rarely use contraceptives to prevent pregnancy and they also seldomly misuse drugs. They also have a possible increase in vaginal immunity as they have decreased levels of estrogen and corticoids and therefore are resistant to Candida species infections. These factors probably contributed to the lowest prevalence of vaginal candidiasis in this age group. The finding is in line with a previous report by Okungbowa et al. [11] who reported a prevalence rate of 10% and 2% within the age groups of 36 - 45 and over 46 years respecttively and he reported that it was probably due to the possible increase in vaginal immunity with age [11].

Observation in this study on the distribution of vaginal candidiasis according to pregnancy trimesters showed that the 3rd trimester had the highest prevalence rate (68.09%), followed by 2nd (21.28%) and the 1st trimester with the least (10.63%) as shown in Figure 2. Pregnant women in the 3rd trimester of pregnancy have suppressed immune system than those in the 2nd and 1st trimesters which steps up the risk of Candida species to become pathogenic. This is due to the emotional stress, which increases as one is expecting a child. At this trimester, an increased level of estrogen and corticoids hormones decreases the level of vaginal defense mechanisms against such opportunistic infections as Candida [5]. These factors contributed to the highest prevalence of vaginal candidiasis in the 3rd trimester of pregnancy. The results are in agreement with a previous study by Sobel et al. [21] who reported the highest prevalent rate of 67% in the 3rd trimester of pregnancy. He reported that it was due to increased emotional stress as a pregnant woman is expecting a child resulting to suppression of the immune system that steps up the risk of Candida species to become pathogenic.

The 1st and 2nd trimesters of pregnancy recorded low prevalent rates of vaginal candidiasis infection. The pregnant women in these two trimesters could have less emotional stresses, high levels of vaginal defense mechanisms against Candida infections as a result of low levels of estrogen and corticoids hormones. Therefore, they have strong immune system against Candida species infections [5]. These factors could have contributed to the low prevalence of the infection in these two trimesters of pregnancy. The findings in this study shows that there was a significant difference in the occurrence of vaginal candidiasis infection in the trimesters of the pregnancy (F = 103.17, p = 0.002, p < 0.050). This was due to the difference in the status of the immune system of the pregnant women in the trimesters of pregnancy. It was also due to difference in the levels of vaginal defense mechanisms against Candida infections as a result of low levels of estrogen and corticoids hormones. This observation is consistent with other reports by Sobel et al. [5] who reported prevalence rates of 11% and 20% respectively. He reported that pregnant women in these two trimesters of pregnancy still have strong immune system against Candida infections. They also have high levels of vaginal defense mechanisms against Candida infections [5].

4.3. Occurrence of Vaginal Candida Species

The results in this study showed that there was a significant differences in the occurrence of the vaginal Candida species causing vaginal candidiasis in the pregnant women (F = 616.62, df = 4, p = 0.000). These results incriminated Candida albicans as the most common vaginal Candida species causing vaginal candidiasis among the pregnant women attending the antenatal clinic of Thika District Hospital (Figure 3). This is probably due to the fact that in the general population, Candida albicans predominates over other species. Candida glabrata is the second one most common, but other species such as Candida krusei, Candida tropicalis, and Candida parapsilosis are also encountered. The results in this study are consistent with previous studies by Akortha et al. [12] and Abu-Elteen et al. [5]. Akortha (2009) reported Candida albicans as the most prevalent vaginal Candida species isolated in pregnant women with vaginal candidiasis followed by Candida glabrata. He recorded prevalent rates of 64% and 32% of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata respectively. Abu-Elteen et al. [15] documented 63% and 30% prevalent rates of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata respectively. They reported that Candida albicans predominates over other species in the population followed by Candida glabrata but other species such as Candida krusei and Candida tropicalis are also encountered.

The current findings however contradicts the earlier report by Okungbowa et al. [11] who reported Candida glabrata as the most common Candida species among the symptomatic pregnant women in Nigeria cities. This may probably be due to significant increase in the incidence of Candida species infections in Nigeria than in Kenya and the fact that non-albicans Candida species especially Candida glabrata continue to replace Candida albicans in causing vaginal candidiasis in pregnant women. In this study, an incidence rate of 36.23% was observed for non albicans species. This could be due to non albicans Candida species emerging as significant pathogens. Reports from other studies showed similar observations [16-18]. An overall non albicans percentage of 24, 17 and 32 respectively were reported by each of these researchers. Therefore, non albicans Candida species are emerging significant pathogens [19]. This variation in reports may be attributed to by different sample size used in the studies.

The results of this study on the distribution of vaginal Candida species within different age groups of the pregnant women (Table 2) showed that a higher frequency of vaginal Candida species (60%) was isolated within the age group 26 - 35 years. This observation is consistent with reports of other researchers [10,11] Sehgal et al. [10] reported a 54% incidence rate within age bracket 20 - 30 years in Northern Nigeria. Thirty five (35%) prevalence of the infection was reported within age group 26 - 35 years in Benin City by Okungbowa et al. [11]. Candida glabrata was isolated at high rate in this age bracket (second after Candida albicans) in all the age groups. This may be as a result of Candida albicans predominating over other species in the general population followed by Candida glabrata [20].

Lower rates of isolation of vaginal Candida species in age groups 36 - 45 years (12%) and over 46 years (1%) was recorded in this study. Women in the age group 36 - 45 are nearing their menopause age and are becoming sexually inactive. This may be the reason why vaginal Candida species recorded at a low prevalent rate in this age group. Women in the age group of over 46 years have reached their menopause age and are not sexually active. They rarely use contraceptives to prevent pregnancy and they also seldom misuse drugs. They also have a possible increase in vaginal immunity as they have decreased levels of estrogen and corticoids and therefore are resistant to Candida species infections. These factors probably contributed to the lowest occurrence rate of vaginal Candida species in this age group. These findings in this study are in line with those of Akortha and Kent et al. [12,20] respectively.

In the present study, it was found that Candida albicans was the most frequently isolated species in the 3rd trimester followed by Candida glabrata. This may be due to the fact that the two Candida species are the most common vaginal Candida species in a population [22]. Candida krusei and Candida parapsilosis were very few and only isolated in this trimester of pregnancy. This could be as a result of these two Candida species not being commonly found in the general population [22]. This is in line with a previous study by Sobel et al. [5] who isolated the species at a rate of 67% in the 3rd trimester of pregnancy. He reported that increased emotional stress as a pregnant woman is expecting a child and decreased level of the vaginal defense mechanisms against Candida species and thus becoming more susceptible to Candida infections contributed to the highest isolation of Candida the species [5].

However, the occurrence of the vaginal species was low in the 1st and 2nd trimesters of pregnancy probably because women in the 1st and 2nd trimesters have low emotional stresses unlike in the 3rd trimester and thus have strong immune system against Candida species. They also have low levels of estrogen and corticoids hormones resulting to high vaginal immunity or defense mechanisms against Candida species infections. Candida albicans was the only Candida species that was isolated in the 1st trimester of pregnancy. The same species was also isolated at the highest rate in the 2nd trimester. Candida glabrata was the second highest Candida species to be isolated in the 2nd trimester. This is because Candida albicans is the most common encountered vaginal Candida species followed by Candida glabrata in the general population than other species [22]. The findings in this study show that Candida albicans is the most frequency isolated vaginal Candida species causing vaginal candidiasis in all the 3 trimesters of pregnancy. This is in consistent with other reports of Otero et al. [22] who reported that the most common cause of vaginal candidiasis in pregnant women is Candida albicans.

5. Conclusion

The prevalence of vaginal candidiasis in the pregnant women was high especially in the age ranging from 26 to 35 years and at the third trimester of pregnancy. Candida albicans was the most prevalent vaginal Candida species across the age groups of the pregnant women and thus incriminated as the most species causing vaginal candidiasis in pregnant women. However, non-albicans Candida species were also isolated and identified, which indicates their emergence as opportunistic pathogens in immunocompromised patients. Therefore, determination of the prevalence of vaginal candidiasis and occurrence of vaginal Candida species in pregnant women will be of importance in diagnosis of the infection and giving better antenatal services in the country. This will go a long way to improve on maternal health services countrywide.

6. Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Kenyatta University and Thika District Hospital management for the approval of this research project. We thank the Hospital laboratory staff members for their contribution in this research work. We are grateful to all the patients and clinicians for their cooperation in this study. Finally, we highly acknowledge the National Council for Science and Technology (NCST), Kenya for giving a grant for this project (Grant number NCST/5/003/PG/86).

NOTES

#Corresponding author.