The Implementation of the Child’s Right to Participation in the Context of a Student-Centered Education System in the Pedagogy of Integration and Decision Making ()

1. Introduction

Burundi, independent from Belgium in 1962, built his education system beside the religious organization functioning in the period ( Kombo et al., 2023 ; Ndayikengurukiye, 2014 ). Burundi has taken part in two PASEC-type international assessments in 2014 and 2019. These assessments covered pupils in grades 2 and 6 of the fundamentals. The assessment focused on the languages of instruction (Kirundi in grade 2 and French in grade 6 in the case of Burundi) and Mathematics. Since 2010, Burundi has entered the “Initiative Francophone pour la Formation à Distance des Maîtres” ( Mazunya & Varly, 2017 ) prompting teachers to inquire what are the needs of their children. They then want to sort out issues in the field of education including e-learning.

The relationship and interconnection of general issues involved in the development of digital skills, an essential precondition for lifelong learning, call for analysis of technology applied to develop skills in education with the inclusion of appropriate core skills whether formal education, with implications on curriculum development or educational policies and more important on rethinking the roles of teachers and learners and transforming the learning environment ( Grimus, 2020 ). The pedagogy of integration in the student-centered system is applied to enhance students’ better understanding of course contents and theoretical knowledge and increasing number of academicians ( Salam et al., 2019 ). As it has been discussed, the dimensions of education integrating technology are pedagogical orientation, pedagogical practices and digital pedagogical competencies ( Väätäjä & Ruokamo, 2021 ), this case should be analyzed elsewhere.

In Africa, under the article 4 of the African Charter on the rights and welfare of the child, in all actions concerning the child undertaken by any person or authority, the best interests of the child shall be the primary consideration ( African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, art. 4 ). This means, in all proceedings affecting a child who is capable of communicating his/her own views, an opportunity shall be provided for the views of the child to be heard either directly or through an impartial representative as a party to the proceedings, and those views shall be taken into consideration by the relevant authority in accordance with the provisions of appropriate law.

“Children’s right to participate is considered pivotal for establishing a culture of democracy and citizenship” ( Correia et al., 2019 ). Laying democracy to children requiring their ideas and opinions is a key to child’s protection. Internationally or world widely admitted, child’s participation policy and programming has been a priority in the Convention on the Rights of the Child obliging countries to involve various efforts ( Collins, 2016 ). The Conventions on the Rights of the Child, stressing the child’s right to participate open this right to even disabled ones. Thus, according to the 1st paragraph of article 23, “states Parties recognize that a mentally or physically disabled child should enjoy a full and decent life, in conditions which ensure dignity, promote self-reliance and facilitate the child’s active participation in the community”. The Convention underlines the child’s right to participation in leisure and cultural activities. Under Article 31, the Convention obliges that “States Parties recognize the right of the child to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts. States Parties shall respect and promote the right of the child to participate fully in cultural and artistic life and shall encourage the provision of appropriate and equal opportunities for cultural, artistic, recreational, and leisure activity ( Nyabenda & Sindayigaya, 2023 ; Sabiraguha et al., 2023 ; Sindayigaya & Nyabenda, 2022 ; Sunzu, 2022c ). Helping the child to enjoy their right to education helps the development of the child’s personality, talents, and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential and the preparation of the child for responsible life in a free society ( Buhendwa et al., 2023 ; Ciza & Sindayigaya, 2023 ; Jonya et al., 2023 ; Mperejimana & Sindayigaya, 2023 ; Ndericimpaye & Sindayigaya, 2023 ). This is the provision of Article 29 §1 a) and d) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and Article 11 §2 a) and d) of the African Charter on the Rights and welfare of the Child.

The chances that children have to participate in child protection services ensures that they have a crucial role in ensuring that a child’s voice is being listened to ( Nduwimana & Sindayigaya, 2023a , 2023b ; Nyabenda & Sindayigaya, 2023 ; Sindayigaya, 2023a , 2023b ) and acknowledged in often sensitive dialogues and this is in the education system ( van Bijleveld et al., 2020 ). “Child’s participation means children are treated with respect and their voices are heard, and children’s rights are made known to children themselves, parents and all those working with children” ( Quaye et al., 2019 ; Ndayisenga & Sindayigaya, 2024 ).

In Burundi, the Article 6 of Law no. 1/19 of September 10, 2013 on the organization of basic and secondary education in Burundi highlights that “the basic and secondary education sector is placed under the responsibility of the State, which guarantees citizens the effective implementation of the right to education”. Article 7 of the same law makes it clear that the Burundian education system opts for a learner-centered pedagogy. The profile of the individual trained in the Burundian education system as organized by the provisions of this law is an individual shaped by knowledge, know-how and interpersonal skills ( Sindayigaya, 2022 ; Sindayigaya et al., 2016 ; Sindayigaya & Toyi, 2023a , 2023b ).

This article targets to analyze the degree of implementation of the child’s right to participate in decision-making in the domain of the education system in Burundi.

2. Methodology

This article is the result of a semi-structured interview conducted with pupils in 4th degree of the Fundamental schools (from 7th to 9th Year of the Fundamental schools) from secondary schools in Bujumbura. The same semi-structured interview was conducted to students in university degrees (Bachelor, Master, and PhD). The survey was dealt in Bujumbura, Burundi. The main topic was to inquire how they experience different ways by means of which they enjoy their right to participation.

The topics developed were around the following questions:

1) Do students vote for their representatives?

2) Are students’ representatives designated by school direction?

3) Do schools organize students’ general assemble?

4) Do schools’ direction consult student representatives in decision making or student themselves in the case they are punished, to help them give their opinions?

5) Do pupils or students participate in setting up or revising school rules, academic regulations, revising course outlines, setting up or modifying legal and regulatory texts governing education?

We used Microsoft Office Excel and SIBM PSS during result analysis and Zotero software in references and biography all along this research.

3. Results

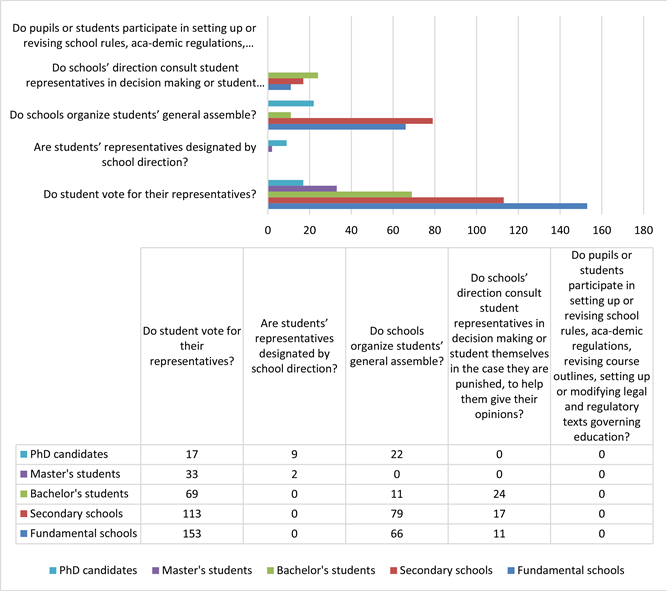

Results to questions are synthetized in the graphic below.

4. Discussion

Results are to be analyzed in different phases of the formal education students’ opinion about representative election, the organization of student general assemble, students opinion before being punished and students’ opinion setting up courses outlines.

4.1. Students’ Participation in the Representative Election

In Burundi, all students from fundamental, secondary schools, and the bachelor’s degree in universities agree that students vote for their representatives. Even in Master’s and PhD degrees, the majority confirm that they votes for their peers as representatives in any required matter (See Graphic 1).

Under paragraphs 2 and 3, Article 5 of the Law no. 1/19 of September 10, 2013, on the organization of basic and secondary education in Burundi, the aim of education is the development of the individual and the formation of a being rooted in his culture and environment, aware of his political and civic responsibilities as well as his duties towards his country and his family. This individual is ready to play a role as a producer and citizen in the economic and social development of the community.

The coordination of school activity is based on the collaboration between the administration and students. To let it be better, schools proceed to setting up class monitors or class representatives. The common practice responds to the need of democracy at school ( Guibet Lafaye & Ferri, 2022 ; Jacqmarcq, 2021 ). On each side (representatives and students represented) the situation of this collaboration means the commitment taken as a constraint or a promise noting the weight of responsibility between partners of any single school leading to specific

Graphic 1. Students views on the implementation of their right to participation in Burundi education system.

feature of cognitive development in adolescence, leading young people to become increasingly aware of what’s at stake in the world around them, and to take a stand for a cause or an idea, thus developing values ( Bois et al., 2021 ).

Under Article 53 of the law on education we cited before, “a school management committee on which parents are represented assists the head teacher in the administration and management of the school”.

4.2. Organization of School Student Assembly

On the matter of organizing general assemblies at school, results shows that 22 out of 26 PhD students who responded to our questionnaire confirm that the doctoral school at the University of Burundi holds general assembly on special issue while none of 35 students in Master’s degree responded that the universities do not hold students’ general assemblies (See Graphic 1). The same results from Graphic 1 show that 55 out of 66 students in Bachelor’s degree tell the schools do organize students’ general assembly. 34 out of 113 students in secondary schools in denying the taking place of students’ general assemblies while 79 (a big part of the respondents of this category) confirm schools do it. The result from fundamental schools students is that 87 out 153 students do not accept that schools holds general assemblies.

The holding of students’ general assemblies is an event in which they decide what to do in special matters. In Quebec (Canada), “the refusal of tuition fee increases, the goal of free education, and more broadly the contestation of a certain model of the university, are at the heart of the student action. But this action also involves an intervention on democracy itself, at once critical of the existing representative democracy and affirming a conception of participatory democracy” ( Leydet & Jellis, 2012 ). In France, students mobilize in the form of a general assembly which is a direct-democratic procedure, in which any student can speak and vote, and in which participants consider themselves legitimate decision-makers by virtue of their gathering alone, a mode of organization used during the succession of student mobilizations that marked the end of the 2000s to examine the Equal Opportunity Act ( Le Mazier, 2014 ). The means by which general assemblies in France have led to the way students may even opt to use strike as a way to express their points of view since the 1960s and the uses to which General Assembly are shaped by the internal struggles of the social, political and trade union groups involved in these mobilizations, a symbolic undertaking to justify them in the name of “democracy” but if invested with a whole range of roles they do not follow democratic norms ( Le Mazier, 2015 ). In some African countries such as Senegal, university students’ general assemblies are used as a way of resistance to democratic transition changes in politics ( Zeilig, 2009 ) and this reason, they try to mitigate them.

4.3. Reception of Students’ Opinion before Getting Punished

Students in PhD and Master’s degrees tell they are not given enough time to express their opinions in case they are accused of violating academic rules (See Graphic 1). The same results reveal that only few students (24 out of 69 in Bachelor’s degree, 17 out of 113 in secondary and 11 out 153 in fundamental schools) accept they are given an opportunity to express themselves before being punished.

However, the best way to engage both teacher and student is to help them work together ( Zhang & Hyland, 2018 ) requiring students’ feedback on any matter and searching how to get along on any issue. Despite students may fail to provide a convincing explanation in foreign languages ( Bai & Hu, 2017 ) it is a teacher’s duty to address students’ opinions especially when they mistake or are astray comparatively to the need or provisions of academic rules. Here, we can invoke the students’ right to a fair trial decided in all fairness ( Mperejimana & Sindayigaya, 2023 ; Sunzu, 2022a , 2022b ). This means, all techniques and strategies used and teachers’ challenges in dealing with students’ disruptive behaviors, implying the inclusion of conflict management strategies classified into three categories:

1) cooperative and problem-solving strategies,

2) avoidance strategies;

3) punishment strategies ( Mahvar et al., 2018 ).

The use of cooperative and problem-solving strategies is expected to facilitate the implementation of effective mutual communication among teachers and students to help them to correct their negative behavior, training and preparing the teachers for dealing with the student’s disruptive behaviors, and using various teaching methods and approaches based on the classroom situation ( Mahvar et al., 2018 ).

4.4. Students’ Opinion Setting Courses Outlines and Legal Text in Education

Results of our research confirm that students in all levels of the Burundian education system do not participate in the setting up or revising school rules, academic regulations, revising course outlines, setting up or modifying legal and regulatory texts governing education ( Mpabansi, 2023 ; Ndericimpaye & Sindayigaya, 2023 ; Sabiraguha et al., 2023 ; Shabani, 2015 ; Toyi & Sindayigaya, 2023 ). They are only beneficiary but are excluded in the steps of mapping the curricula. Burundian education system is accused of the Standards deviation on the means, manner or the way through which schools misunderstand education policy ( Spillane, 2009 ). Implementing the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (Art.4) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (Art.3) that call for the States to primarily consider the best interests of the child in all actions concerning the child undertaken by any person or authority ( Kombo et al., 2023 ; Oladejo et al., 2023 ; Shabani, 2015 ; Shabani et al., 2014 ). This obliges authorities and decision-makers that a child who is capable of communicating his/her own views to be given an opportunity to express their views that must be taken into consideration. This means, in any case implying decision-makers need to help students be involved in the setting the learning policy applying the state education reform works ( Cohen & Hill, 2008 ; Henry et al., 1997 ). This is also applied during the privatization of public sector education, mapping and analyzing the participation of education businesses in a whole range of public sector education services which is recommended in UK and overseas ( Ball, 2009 ). By no means, students participation during every change applied in the education system is indispensable and is in every debate about education system ( Ball, 2021 ). This is a key to achieving the target of the student-centered education system approach that Burundi already adopted ( Nduwimana & Sindayigaya, 2023a , 2023b ).

5. Conclusion

Burundi is a party to the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child and the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Thus, in the context of Article 4 of this charter, Burundi needs to apply the child’s right to participation in all contexts including the education system. In the same context, Burundi is applying the system of education in the way known as “students-centered” meaning that everything done in education must be oriented in the context of the child’s best interest. This research aims to inquire by means of a questionnaire in a semi-structured interview with students from all levels of education systems in Burundi. On the matters like choosing their representatives, delivering speeches or giving their opinions before getting punished, participating in school general assemblies or appointing school curricula…, results show that there is a long way over to get to where it should be.