Well-Being Status of the Informal Workers in Bangladesh: An Inside into Personal, Social, and Economic Aspects ()

1. Introduction

Covering a wider range of economies, the informal sectors have a significant contribution by creating employment, enhancing production, and generating income for the vast majority of workers in the rural and urban labour market. It represents two-thirds of worldwide employment and contributes more than 40% of global GDP. In South Asia, it is estimated to stand at 80 to 90 percent of the labour force ( ILO, 2010 ). In Bangladesh, it covers 85% of the total employed population at a national level ( LFS, 2016 ). This employment offers a necessary survival strategy for people who are unrecognized, unregistered, unregulated, or lack labour legislation and social protection.

The informal economy is marked by decent work deficits and a disproportionate share of the working poor ( Muchichwa, 2017 ). Though the workers prevail under denied employee rights—fair wages, the right to raise their voice and join a union, social safety, and security, they have to enter here not by choice but by necessities. The activities in the informal sector pay incomes and livelihoods on a minor scale, many people who are working in the informal sectors are visibly under poverty thresholds and often succumbed to precarious working environments. Workers in the informal sector have a high illiteracy rate, low skill levels, inadequate training opportunities, less well-being, uncertainty about work, and longer working hours. Moreover, informal sector workers have few opportunities for collective bargaining and social dialogue to ensure their rights and employment status. With such circumstances, the well-being status of the informal workers is under threat, which leads the workers to live a precarious life.

Good standards for the well-being of workers play a vital role in creating a sustained society where workers feel satisfied and they can be more productive and loyal at their workstations. The well-being status of workers depends on several factors—personal, social, economic, and so forth. For an employee, sometimes it is more difficult to carry a standard level of well-being owing to the low level of income and other benefits. The relentless pursuit of economic growth is also unable to ensure a minimum wage for informal workers. However, investment in social changes and redistribution of wealth could bring a standard of well-being for workers. Well-being has here been addressed as a holistic view of subjective and objective perspectives. To enhance their well-being, informal workers should many (if not all) be provided by a contributory scheme linked with limited earnings supplemented by subsidies from employers ( Wagstaffa & Manachotphong, 2012 ). This scheme may vary depending on the types of workers and their level of skills.

In light of changes in the conditions of workers in the informal sector, along with social responsibility, employers can come forward to make better payments to the workers. Since financial strength in many cases determines the worker’s well-being, investing in people’s well-being sets the foundations for stronger and more sustainable long-term economic growth ( Nozal, Martin, & Murtin, 2019 ). With such a condition, it is inevitable to explore workers’ well-being in the informal sector of Bangladesh focusing on the personal, social, and economic well-being aspects. In exhibiting the elusive objective, the current study has focused on the three perspectives of well-being: 1) worker’s personal well-being, 2) their social engagement, and 3) economic wellness of workers. The paper is structured as follows: inside understanding of well-being with its three aspects. Then, the study is followed by the research purpose and methodology, which lead us to ways to explore the research objectives. Lastly, the rest of the paper presents the well-being trajectories of the workers in the informal sector of Bangladesh.

2. Inside Understanding of Well-Being

The concept of well-being for individual or collective approach is not new. It was incorporated into neo-classical economics as a way of attempting to explain the behaviour of individuals. In this context, well-being is linked in its origins to Bentham’s utilitarianism in which individuals would seek to maximize their satisfaction and happiness ( May, 2007 ). Well-being further goes to connect the sense of intellectual, spiritual, and cultural pleasure.

In labour market, the sense of workers’ well-being is directly related to several components—the personal perspective of individual happiness, social satisfaction of workers, and economic ability of individuals. Personal well-being relates to the concepts of subjective and emotional well-being, psychical and mental well-being, satisfaction with life, and happiness ( Musek & Polic, 2014 ). Moreover, it is found from the Personal Well-being Index (PWI) that an individual’s happiness depends on seven life domains, namely, the standard of living, personal health, life achievement, personal relationships, personal safety, community connectedness, and future security ( Lau, Cummins, & Mcpherson, 2005 ). Through analyzing a personal lens, an individual’s well-being reflects the determinants of cultural context, sense of fulfillment, feeling of contributing, personal relationships, and so forth.

Social well-being connects one’s ability to keep meaningful positive relationships with and participate in different social events with family, friends, neighbours, and co-workers, and having improved social status. It refers to the overall quality of life and satisfaction that individuals or communities experience within the social dimensions of their lives and is associated with the total condition of individual and community life. Social well-being largely depends on the level of material possessed or accessed as that supports all other parts of life and maintains social status ( Roy, 2018 ). It encompasses various aspects of social life and relationships—social support, a good relationship with others, community engagement, safety and security, and cultural and recreational activities.

Economic well-being demonstrates people’s improved consumption expenditure. It makes people capable of having their most basic survival requirements, i.e. income and assets that lead them to prosper. Additionally, the economic well-being of individuals encompasses a wide range of factors including level of wages, income, employment, wealth, financial security, saving and investment, income inequality, access to essential services, and overall economic stability. It is a crucial factor in the overall well-being of a worker or individual but workers in the informal sectors are generally underprivileged in this state of well-being. Enterprises in the informal sector are not willing to provide a substantial amount of wages and other admissible benefits to the workers that enhance the economic well-being of the workers.

By and large, enterprises and in some cases, organizations are gradually accepting the necessity of workers’ well-being and giving value to workers as human resources. A lack of recognition of the need to promote workers’ well-being may give rise to workplace problems—stress, bullying, conflict, and mental health disorders ( ILO, 2021 ). In that case, a potential solution would be the combination of ensuring safety, social participation, fair wages, a decent working environment, ensuring the personal, social, and economic well-being of the workers.

3. Research Purpose

The informal sector of Bangladesh’s economy is considered to be the highest provider of employment which also leads to substantial economic growth but the workers of this sector remain confronted by claims of precarious working conditions. This paper aims to state whether and to what extent the well-being of workers in the informal sector has taken place. The specific objectives are:

· Revealing worker’s personal well-being in the informal sector;

· Providing the portraits of social engagements of the workers;

· Presenting the economic well-being of informal workers in Bangladesh.

Keeping more concentration on a country’s growth and development sometimes a large segment of workers particularly in informal sectors are being excluded from the development trajectories. Without knowing the state of workers’ well-being, development as understood through the process of economic growth and upgrading is not necessarily sufficient to support an improvement in labor conditions ( Anwar & Graham, 2019 ). It is said that the integration of workers into the high-valued production network and distribution of benefits can lead to improving the worker’s well-being conditions which needs to be explored in the informal sector of Bangladesh.

4. Research Method

The present research has employed a mixed-method approach to meet the objectives of the study. To conduct the research both qualitative and quantitative data have been collected to assess the state of worker’s well-being in the informal sector of Bangladesh. The data has been collected from both primary and secondary sources. Primary data sources are basically from the employees of the study area. Primary data of this study have been collected through questionnaire survey, in-depth interviews, observation, Focus Group Discussions (FGDs), and Key Informant Interviews (KIIs). Secondary data sources cover relevant books, journals, dissertations, thesis papers, newspapers, publications of government institutions, policy reports of government and international organizations, and so on.

4.1. Selecting Study Areas and Population Domain

In many countries, the informal sector plays an important role in employment creation and income generation. Country having high population growth like Bangladesh, the informal sector tends to absorb most of the workforce and has been playing an important role in growth dynamics by providing 89% of the total number of jobs in the labour market. The distribution of informal employment across the broad economic sectors is 72% in services, 90% in industry, and 95% in agriculture. The distribution of informal employment over administrative divisions is Rangpur (89%), Rajshahi (87%), Chittagong (84%), Dhaka (84%), Khulna (83%), Barisal (81%) and Sylhet (79%) ( LFS, 2016 ). Considering the informal employment density (the highest, medium, and lowest), three divisions—Rangpur, Dhaka, and Sylhet have been selected with two districts from each having one Sadar district for the current research.

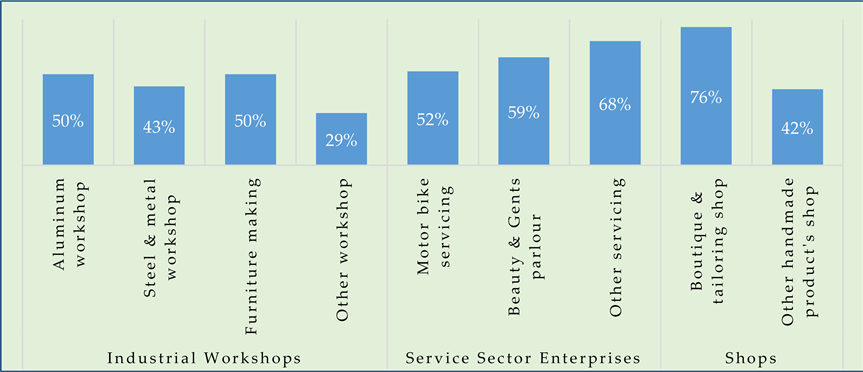

Workers engaged in informal employment are mostly in agriculture, services, industrial enterprises, shops, hunting and forestry, wholesale and retail trade, manufacturing, transport, storage, and communications sectors. These various types of informal enterprises can be categorized into three broad economic sectors—agriculture, industry, and services. The respondents have been selected from industrial enterprises, service sector establishments, and shops. The agriculture sector mostly possesses landless or marginalized labour. Thus, this sector has been excluded. The three enterprises have been grouped into: 1) Industrial Workshops—Aluminum workshop, Steel & metal workshop, Furniture making: 2) Service Sector Enterprises—Motorbike servicing, Beauty & Gents Parlour: 3) Shops—Boutique & Tailoring shop, other handmade product’s shop where employees are the respondents for the study.

4.2. Sample Determination and Distribution

A huge number of workers are employed in informal sectors. The whole population is unknown and impossible to individually identify. Therefore, the current study has been conducted based on a non-probability convenience sample of the informal workers (n = 255) in Bangladesh. The number of samples has been drawn from industrial enterprises, service sector establishments, and shops (Table 1).

Respondents distribution according to areas was kept to the same range—85 respondents from each area. Interviewees took from 50% from industrial workshops, 32% from service sector enterprises, and 18% from shops (Table 1).

4.3. Different Features of Interviewed Workers

Employee sex distribution can depict a picture of whom and how many are engaged in informal sectors. Male workers are still in a significant number of these sectors. According to Labour Force Survey 2016-2017, the labour force participation rate of the population aged 15 or older at 58%, with 80% male and 36% female which motivates the current research to take 78% male and 22% female (Table 2). Female workers are mostly found where there are more female customers like boutique shops and beauty parlors whereas male workers are more concentrated in industrial enterprises.

For general economic interest, educational attainment is always widely considered one of the important factors which envisage labour market outcomes and economic and social success. The connection between education and income is strong. Employment in the informal sector is mainly linked with education in lower label and more education generally provides better employment in formal sectors. A majority of informal workers—33% have just completed the Primary School Certificate (PSC) level while only 2% are graduates and above and 6% have completed their higher secondary certificate. Workers who have completed a Junior School Certificate (JSC) are also high (26%). It can be demonstrated from the data that the number of workers decreased with the education level increased.

![]()

Table 1. Distribution of respondents (workers) by types of areas and in broad sectors.

Source: Field data 2020-2021.

![]()

Table 2. Characteristics of interviewed workers.

Source: Field data 2020-2021.

Globally, the share of informal employment in total employment is higher among young workers (aged 15 - 24) than other adult workers. In developing countries, almost all employed population who is working in the earlier age group and older age groups are informally employed ( WIEGO Foundation, 2021 ). Bangladesh as a developing country mostly takes on its total informal employees’ age ranging from 15 to 35. This age distribution shows that the middle age group is usually more in numbers. The current study has depicted that more than 24% and 23% of workers age is between 25 to 29 years and 30 to 34 years respectively (Table 2). Generally, informal enterprises are more likely to employ the young age population, therefore middle-aged people are more employed.

5. Research Findings and Discussion

A central argument of this article is to find whether and to what extent the well-being of workers has taken place in the informal sector of Bangladesh. For stating well-being status, it has been considered three important factors—personal well-being signifies health status and work-life balance of workers, social well-being connects a good relationship with family members, friends, society, and participation in social events; and economic well-being relates to earning, expenditure, and saving capacity of the workers.

5.1. Personal Well-Being

Personal well-being signifies the work-life balance and the health status of individuals and their families. The informal labour market in Bangladesh underwent a significant downturn in workers’ well-being in terms of their life and work, and the health status of them and their families. Over 60% of workers cannot spend time with their families due to long working hours, individual work pressure, and work delivery time. Still, nearly 48% of workers and their families do not get medical facilities even if they fall into acute health problems that have been reported from FGDs. Sometimes, the workers cannot afford to bear the medical cost owing to the shortage of income, earning insecurity, and other income sources mentioned by one key informant interview.

The highest percentage of workers, almost 70% in boutiques and tailoring shops can spend more time with their family than the lowest one that works in motorbike servicing (21%). In between this range, there are 30% of workers in steel and metal workshops, 32% in aluminum workshops, 34% in furniture-making enterprises, and 54% in beauty and gents’ parlour can spend time with their families (Chart 1).

The average weekly time workers spend in their household is very insignificant. Employment uncertainty and personalized negotiating relations between employees and employers may sometimes create pressure on long-hour work. Therefore, workers in informal sectors cannot manage time for their families or even for themselves.

Several studies have pointed out that stability and security of work in an enterprise have the largest effects on work-life balance ( Hussain & Endut, 2018 ). In addition, the lack of several types of paid leave—annual leave, parental leave, sick leave, and festival leave –affects the work-life balance of informal workers.

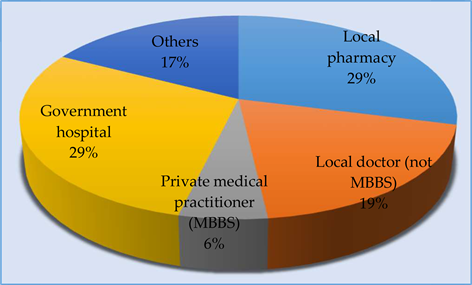

It is seen from this study that more than half of the informal workers and their families do not get medical facilities, but the rest who get those facilities, mostly from government hospitals and local pharmacies is around 60%. Very few workers (19%) get medical facilities from other sources like local non-MBBS doctors, private MBBS medical practitioners (6%), and others (17%) (Chart 2). These findings show that a vast majority of workers engaged in informal activities are under the threat of ill-health conditions that may not provide them with personal well-being and lead them and their families to an indecent life. Good health status can promote the working capacities of individuals and increase the quality of their life ( Thanapop, Thanapop, & Keam-Kan, 2021 ). Among different informal enterprises, the workers in boutiques and tailoring shops receive more healthiness (75%) than those engaged in other enterprises, i.e. aluminum workshops, steel and metal workshops, furniture making, motorbike servicing, beauty

Source: Field survey 2020-2021.

Chart 1. Workers spending time with their families by sectors.

Source: Field survey 2020-2021.

Chart 2. Place from taking medical facilities.

parlour, that vary from 43% to 59% (Chart 3).

Since half of the workers in almost all informal enterprises do not get medical care facilities, sudden health hazards may bring them lower income on account of minimum work days or their complete inability to work. This, combined with the attendant increase in out-of-pocket health expenditures, can push households into poverty which they might find difficult to escape from ( Dike, 2018 ). However, access to health insurance schemes or free health care facilities provided by employers or the government may save them from out-of-pocket payment for treatment because most of these workers earn daily and always survive under financial volatility. Nearly 60% of the workers and their families visit doctors once or twice, and 13% of workers even did not go to doctors in the last six months. It predicts that the health checkup tendency of workers is very low. Only 6% of workers visit doctors for regular checkups; conversely, the majority of them (40%) go for major treatment. Health is given a low priority and their tolerance level towards the sickness is very high. Whenever they get an ailment, go to local doctors, as claimed by FGD participants in Rangpur.

For balancing work-life balance, personal well-being plays a dominant role. However, the informal sector workers are under a downward spiral in their well-being. The majority of the workers cannot spend time with their family members due to their workplace pressure. They cannot avail of medical facilities because of their low income or income insecurity. In case of acute health problems, less than fifty percent of the workers visit doctors and receive treatment from government hospitals. The informal workers are not covered by any medical insurance or free health care facilities provided by employers.

5.2. Social Well-Being

The sense of being connected with family members, friends, and society is the

Source: Field survey 2020-2021.

Chart 3. Taking medical facilities by sectors.

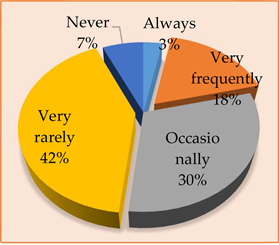

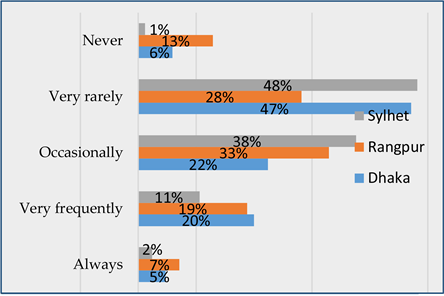

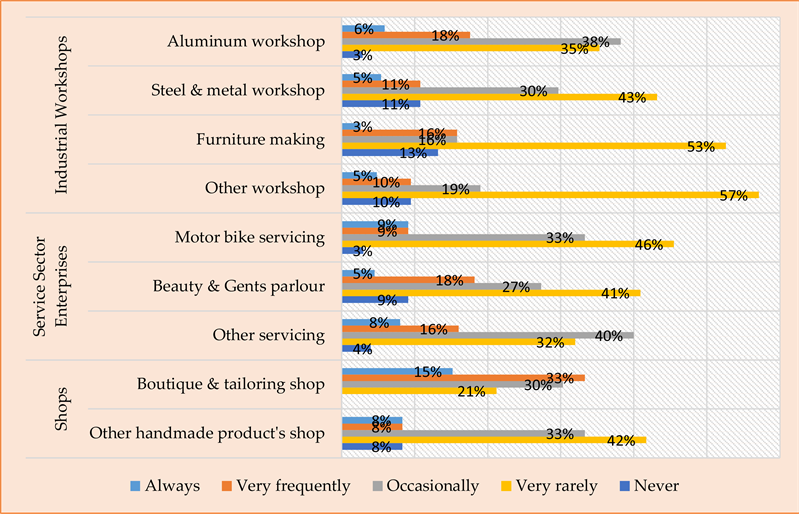

underpinning of a worker’s social well-being. Due to daily long hours of work and lack of paid leave, workers in informal sectors can hardly attend different social occasions—parties, meetings, functions, congregations, and get-togethers. The rate of workers’ participation in different social events is very low. More than 42% of workers reported that they rarely participate in various social events. About 30% of workers said that they occasionally participate in such kinds of programmes. Regular participation is very low. Findings show that only 3% of workers always attend their friends’ family or relatives’ occasions. Nearly 7% of workers have said that they never participate in any social events (Chart 4). In different regions, workers have different trends in joining community events. Nearly similar percentages, 47% - 48% of workers participate very rarely in Dhaka and Sylhet respectively, which is lower (28%) in Rangpur. Only 19% - 20% of workers in Dhaka and Rangpur join different social events very frequently.

Occasional participation is 22%, 33%, and 38% in Dhaka, Rangpur, and Sylhet respectively (Chart 5). It is evident from this study that average participation in social events by workers in informal sectors is very low. It may very often impede their social well-being.

Source: Field survey 2020-2021.

Chart 4.Workers participation in social events.

Source: Field survey 2020-2021.

Chart 5. Workers participation in social events.

Cooperatively, female workers are lower in this regard, and quite often they cannot manage time to participate due to their family chores. Several in-depth interviewers in Rangpur have pointed out that they cannot manage time, mainly for their family maintenance, to participate in such events. Coming back home after a long time of work, they have to spend time, more than their husbands, for caring their family, children, and other members. Financial inadequacy is another factor behind their non-participation in such events.

From this study, it is seen that 40% - 60% of workers in all informal enterprises participate in different social events very rarely. Conversely, workers of boutiques and tailoring shops can manage more time to join very frequently and it is nearly 33% among other informal workers followed by 18% of workers in beauty and gents’ parlours, 18% in aluminum workshops, only 11% in steel and metal workshops, 16% in furniture making, and 9% in motorbike servicing enterprises (Chart 6).

In every sector, it is seen that worker’s social well-being is not improved due to a lack of joining social events, financial instability, or less leisure time. Employers can contribute in some cases to make workers finically a bit capable by giving some festival bonus. As employees’ well-being by and large is business well-being by getting more output, and best effort, to that point employers can come forward to this extent. However, the vast majority of informal entrepreneurs don’t ponder about their responsibility to support employees and boost their social well-being. Even though strong social relationships are among the

Source: Field survey 2020-2021.

Chart 6. Workers participation in social event by sectors.

most fundamental of human needs, just 5% of workers strongly agree when asked if their enterprises help workers build stronger personal relationships, while most employees disagree with this statement ( Rath & Harter, 2010 ). To boost employees’ work quality, safety, buyer engagement, or even employee satisfaction at work, social relations or in other words social well-being is important which can be made by creating quality social time in work days or beyond (in-depth interview).

Connecting with family members or spending quality time with them or with friends may enhance the social well-being of workers. Due to long hours of work or paid leave workers can hardly spend time in different social events. Strong social relationships sometimes increase the sense of societal security and human dignity. Thus, the social well-being of informal workers is not adequate to live a better life which influences them not to concentrate properly at work and boost productivity.

5.3. Economic Well-Being

Economic well-being which is an important indicator that signifies individual well-being and determines the overall comfort of an individual includes consumption expenditure and purchase of durable goods. An adequate level of economic well-being leads employees to afford their basic needs. But inadequate financial security can bring anxiety, stress, sadness, dissatisfaction, and poor mental health to workers, which hamper their productivity. Some evidence also shows that people who attain good standards of economic well-being at work are likely to be more inspired, more trustworthy, more productive, and provide better customer satisfaction than individuals with poor standards of economic well-being at work ( Jeffrey et al., 2014 ). In informal sectors, workers are aiming to achieve economic strength to satisfy consumption expenditures for a family but quite often are incapable of doing so (key informant interview).

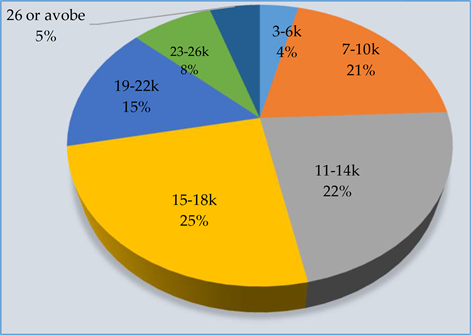

One quarter of the informal workers spend BDT 15,000 to 18,000 monthly for their consumption expenditure which includes food, amount of debt repayment/saving, and education of their younger siblings and children. Nearly 22% and 21% of workers spend BDT 11,000 to 14,000 and 7000 to 10,000 respectively for the same purposes. Few workers (8%) reported that their total expenditure is BDT 23,000 to 26,000. Only 5% of workers spend BDT 26,000 or more for their total family expenditure (Chart 7). Area-wise analysis for consumption expenditure shows that 31% of workers in Sylhet and 25% in Dhaka spent BDT 15,000 to 18,000 monthly. Whereas about 34% of workers in Rangpur manage their consumption cost by BDT 11,000 to 14,000 in a month, which indicates that the informal sector workers in Rangpur lead comparatively measurable life than those of Dhaka and Sylhet.

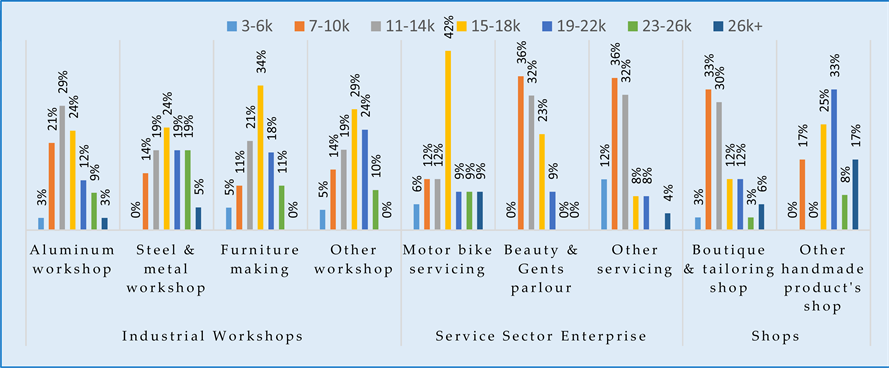

Due to the earning differentiation, workers in various informal sectors have different patterns of consumption expenditure. About 42% of motorbike workers and 34% of workers in furniture-making enterprises spent BDT 15,000 to 18,000 monthly which is higher among other informal sectors like aluminum workshops, steel and metal workshops, boutiques tailoring shops, and so on. From 33% to 36% workers in beauty parlour, boutiques tailoring shops and other service sectors’ workers report that they can spend BDT 7000 to 1000 for their family expenditure (Chart 8). Round the year, nearly all types of informal workers have to suffer financially on account of minimum wages, income insecurity, or having no opportunity for extra income or no other additional income sources.

The purchasing capacity of durable goods—furniture, mobile phones, bicycles, televisions, refrigerators, and gold ornaments—is another indicator of representing the economic well-being of workers. It indicates how much the workers and their families are economically solvent. However, only 33% of workers have

Source: Field survey 2020-2021.

Chart 7. Monthly household’s expenditure.

Source: Field survey 2020-2021

Chart 8. Monthly, food expenditure for family by sectors.

reported that they can afford to buy any durable goods during the year. Conversely, three-fourths of the workers cannot go for those durable goods in a year besides having much desire to occupy those products. This trend of purchasing durable goods indicates that the economic condition of workers in informal sectors is not good. Several in-depth interviewers have stated that most of their earning is spent on consumption expenditure only. They cannot save enough money to purchase furniture, mobile phones, gold ornaments, or other durable goods. That is how workers’ dreams remain unfulfilled for a longer time (FGD).

Purchasing durable goods among different informal enterprises is significantly higher in motorbike servicing and boutique and tailoring shop workers than those of other enterprises. This trend is lower in the steel and metal workshops, aluminum workshops, and beauty & gents parlours. Due to the lack of saving capacity of workers, it is difficult to diffuse their financial capacity into different durable goods called luxury goods. A study has found that the propensity to save among informal workers is very low due to low income; that shows one unit change in income variable increases the propensity to save by 0.129% ( Addai, Gyimah, & Owusu, 2017 ). To enhance the economic well-being of workers, there is an urgent need to fix basic pay or minimum wage. If the workers can earn a bit more than the existing level, they can bear their consumption expenditure, save, and purchase their desired goods called durable goods. The evidence demonstrates that people who achieve good standards of well-being at work are more likely to exhibit a range of skills that will also benefit their employers ( Jeffrey et al., 2014 ). Therefore, economic well-being not only brings satisfaction to employees, but also enhances the employer’s business growth in the long run.

For leading employees to afford their basic needs, an adequate level of economic well-being is required. To enhance the economic well-being of informal sector workers, fixing basic pay or setting a minimum wage is essential. Workers who attain a substantial standard of economic well-being contribute to more productivity. However, less economic well-being makes workers more stressed, anxious, dissatisfied, and have poor mental health, which sometimes decreases their productivity.

6. Conclusion

Globally, the informal sector is considered one of the major employment sources for more than two billion workers covering over sixty percent of the adult labour force and contributing more than forty percent of global GDP. The informal sector pays incomes and livelihoods on a minor scale, many people who are working in the informal sectors are visibly under poverty thresholds and often succumb to precarious working environments and the overall well-being status is under question.

As good standards for the well-being of workers play a vital role in creating a sustained society where workers feel satisfied and they can be more productive and loyal at their workstations. Whereas the well-being status of workers depends on several factors—personal, social, economic, and so forth. But sometimes, it is more difficult for workers to maintain a good standard of well-being owing to the low level of income and other benefits. Personal well-being implies the work-life balance and health status where more than sixty percent of workers can’t spend quality time with their family due to long working hours and overtime work pressure. Moreover, they can hardly attend different social occasions—parties, meetings, functions, congregations, and get-togethers, which reflects the low level of social well-being of workers. Whenever they have acute health problems, still nearly half of the workers can’t get medical facilities putting down to the problems of medical expenses and access to health.

Additionally, the state of economic well-being shows that the consumption expenditure and capacity of purchasing durable goods is under expected level and workers have to suffer financially on account of minimum wages, income insecurity, or having no opportunity for extra income or no other additional income sources. Due to the earning differentiation, workers in various informal sectors have different patterns of consumption expenditure whereas workers in furniture-making enterprises have comparatively higher purchasing capacity. The amount a worker earns is spent mostly for consumption and for other survival purposes, which indicates the lower capacity of expenditure of other durable or luxury items.

Overall, the workers in the informal sector are often characterized by long working hours, low levels of wages, unhealthy working conditions, and are not protected by any labour legislation. Moreover, the state of their well-being mainly personal, social, and economic well-being is not achieved at their desirable level due to several factors, particularly wages, incomes, and long working hours.