The Role of the “Reproduction” 乃 Character in Chinese Writing: 282 Characters and 59 Definitions ()

1. Introduction

The acquisition of Chinese characters and their meanings by the non-native speaker is a particularly onerous task. “While learning any language involves a great deal of effort, learning a character-based or logosyllabic language like Chinese can prove especially challenging for learners accustomed to syllabic writing systems such as English and German,” writes researchers at Montclair State University (Olmanson & Liu, 2018) . Therefore, any insight into the learning of Hanzi—the Mandarin word for the Chinese written language—is a boon. One such insight is to recognize that Chinese has semantically meaningful substructures that play a role similar to that of Latin and Greek roots just like in English has Latin roots. In English, those Latin and Greek roots are really “the Legos of Linguistics”: meaningful subunits that can be assembled into a semantically meaningful unit that has a relationship to its subcomponents. “Bicycle” can be decomposed into “two circles” because “bi” in Latin means “two” and “cycle” is a “circle”—and that’s what a bicycle looks like. “Monarchy” can be broken down into “one king” because “mono” means “one” and “arch” stands in for “king”—the king’s power arches over the populace. About 80% of Chinese writing is considered similarly decomposed. Hanzi already has two recognisable substructures: the first, known as the radical or “bu4 shou3,” contains the meaning; and the second, known as the phonetic component, does not have a particular name in Chinese, though it is often referred to as the “pian1 pang2” (which could mean either component, and thus is not specific ( Radical (Chinese Characters) , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radical_(Chinese_characters)); the lack of a universally recognized term for the phonetic component of a Chinese character is part of the frustration when researching and discussing Hanzi). The phonetic component is often alleged to contribute no meaning to the character—but does it? And if so, how much? That’s what the invention of HanziFinder was set out to explore.

Using the first substructure search engine of Chinese characters, HanziFinder (pat. pending; patent application published July 2023), which my colleague Chao Xu and I built, we can make a list of characters containing a predesignated substructure from our database of 88,884 characters. By taking this list, and then acquiring definitions from Chinese Text Project and/or Wiktionary, we can sort these definitions by meaning. Characters containing a particular substructure have meanings that often cluster around a small set of themes. This clustering can be useful as a prediction tool. A pie chart of semantic probability for any one substructure can be created, visually demonstrating the clumping phenomenon. The “weight” of a substructure in driving the meaning of a character is quantifiable by comparing the meanings of many characters containing that substructure, clustering them by similarity of meaning, and then dividing the number of characters within each cluster by the total number of characters with meanings. (Characters without meanings are recorded but not included in the tabulation.) In the case of “be” 乃, a character containing this structure as a substructure has a 59% likelihood of having a meaning associated with reproduction, a 24% likelihood of having a meaning associated with utility, and a 17% likelihood of having a meaning associated with a punitive situation (Figure 1).

![]()

Figure 1. Pie chart of semantic probability for 乃-containing characters plus a breakdown of data.

2. Methods

Our 88,884 characters came from the HanaMinA typeface found for free on GitHub. Using a drawing tool that Chao created, Meiqin Xia, Huimin Luo, and Wenqing Huang spent over a year’s time redrawing this set of 88,884 characters into searchable nodes and lines. Quality control (which took another year) was handled by Iris Guo. Organizational help came from Maggie Li.

Once the database was created, the tool was refined by Chao to search these nodes-and-lines structures for target candidates. HanziFinder can assemble a list of characters containing a specific substructure. Using this list, definitions can be obtained from resources such as Chinese Text Project and Wiktionary. Using the definitions as the sorting criteria, similar themes are categorized together (as seen in the Data section below). A pie chart representation further illustrates the clustering phenomenon, enabling the quantification of a substructure’s weight in driving a character’s meaning.

The subjective nature of clustering definitions under an umbrella concept is recognized by this author, however, this clustering serves the purpose of creating a context with which the Chinese reader can recognize the related nature of such 乃-containing characters as, for example, “fatigue, paralysis of the foot” 疓, “late” 莻, “slow” 䋼, and “thick” 䚮: all consequences of pregnancy. At the same time, these words could be considered negative or punitive, most assuredly because nature isn’t equitable, and the brunt of reproduction is born by the female. In both cases—whether one argues for classifying these as reproduction-related as I have, or punitive (as one could reasonably argue)—the establishing of an overriding pattern where “structure equates to concept” facilitates vocabulary retention as well as anthropological research.

3. Chinese Writing Uses Two Coordinates to Hew Irrelevant Possibilities

Chinese writing is a gestalt: often two or more substructures coalesce into meaning. The radical–phonetic, or the “x, y” characteristic of Chinese writing, is a very rational strategy when attempting to narrow the semantic space of a character. If a person wants to mark a point in two-dimensional space, they will use a graph with two axes: x and y. The two numbers along those axes that correspond to that marked point in space are called “coordinates.” This “two-coordinate” method is used to pinpoint one location in two-dimensional space so that it can be reliably communicated to others. The strategy of using two coordinates to communicate one locus is logical; In fact, the same system is used in written language, but those two coordinates are: 1) the radical/determinative and 2) the phonetic/pronunciation. Chinese Hanzi, Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, and Sumerian cuneiform all employ this bipartite method ( Determinative , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Determinative).

Two different axes—x and y—work together to hew irrelevant possibilities. Two different channels for recording data allow their intersection to enhance the limitations of written language, which can only be seen and not heard. Both semantic and sound data are encoded in these determinative/phonetic-based language scripts, but due to the proliferation of homonyms, a selection process occurs. Many choices with similar sound and tone often create confusion, so much so that a common method Chinese speakers utilize in order to hone in on a word is to use a commonly known form of the word that contains the character they mean, then the possessive 的 (de0), and then the exact character the person is talking about, i.e., “the ‘cow’s milk’ ‘milk’ [character]” “牛奶的乃.” The fact that this is necessary is indicative as to how many homonyms exist in Mandarin/Hanyu.

For example, the word “be” 乃 (nai3) is the same pronunciation as “milk” 奶 (nai3), and both contain “be” 乃 in their structures, possibly because a baby’s existence depends upon mother’s milk. If a mother dies, often the child does as well. This “be” 乃 structure is not considered a radical; perhaps because it serves as the phonetic; yet it is also found in the word for “pregnant” 孕. “Pregnant” 孕 is pronounced “yun4,” which is not the sound of either of its components: “be” 乃 (nai3) or “child” 子 (zi3). The fact that “be” 乃 is in both “milk” 奶 and “pregnant” 孕 bears analysis (Figure 2).

![]()

Figure 2. The relationship between existence (“be”), “milk,” and “pregnant”—all aspects of reproduction—shows up in Hanzi.

The character “be” 乃 is like a radical in phonetic clothing, possibly because propriety dictates that we do not recognize the similarity between the shape of 乃 and the shape of the body of a pregnant female. The double-lobed 乃 has so many meanings related to procreation because the shape of a pregnant female mammal’s body and the shape of female mammal breasts are congruent, consequently one symbol can have multiple associations, especially when it comes to reproduction. The character 乃 resonates with many positive facets of pregnancy, including the 乃-containing characters “to be filled, curvaceous” 盈, “blessings, happiness” 礽, “outstanding” 隽, and “talented” 㑺.

Though a standard “x, y” graph would bequeath x and y as having equal importance, in written language it would seem that the pronunciation component’s significance has been minimized. The fact that “be,” “milk,” and “pregnant”—all aspects of reproduction—share a similar component—乃—suggests that this 乃 structure has a relationship to reproduction, and, as such, has meaning, which is what defines a radical.

Recognizing the correlation between structures, substructures, and meaning could boost literacy in Hanzi because pattern creates a path to vocabulary retention. The fact that there appears to be more semantic information being communicated in a Hanzi character than is currently realized could be leveraged for the student’s benefit, and perhaps for the historian’s as well.

4. The Precursors to “Pregnant” 乃 Exhibit Consistency

On Hanziyuan.net, a Chinese etymology site, the precursors to “pregnant” 孕 (Figure 3) appear to be (from top to bottom): Oracle: a woman with an enlarged stomach—on close inspection, one can even make out that the baby’s head is in the downward position; Seal: a pregnant female mammal body with a baby coming out below; Liushutong (2nd century BC): (first two) unknown. The last Liushutong character resembles the Seal character. Both of them resemble the Hanzi character (simplified and traditional) for “pregnant” 孕 ( Sears , http://hanziyuan.net/#乃).

![]()

Figure 3. The precursors to “pregnant” 孕 on HanziYuan.net.

The character “female” 女 signifies for key characteristics known to be under female providence: “milk” 奶 and “pregnant, to conceive” 㚺 (an older character). Pregnancy often results in a baby. Therefore, this “pregnant” 孕 concept can logically be used with the traditional “fish” 魚 radical found in the character “small fish, spawn, or roe, frog group” 䱆 ( Sturgeon , https://ctext.org/dictionary.pl?if=en&char=䱆). “Fish” 魚 plus “pregnant” 孕 means “roe.” (There is no precursor listed for 䱆.) The literal translation “fish pregnant” logically equates to “fish eggs” because women and other female animals carry eggs/ovum.

5. Noah’s Ark Is the World’s First Sex Education: 2 by 2, Male and Female

Human survival was based upon recognizing the importance of reproduction. The first book of the Bible is Genesis, and it is about generating more. One of the first stories is Noah’s Ark, which is the world’s first sex education: two by two, male and female. A less specific version of this story is from the Epic of Gilgamesh, which is 2500 years older than the Bible. The importance of owning breeding pairs was propagated via written language. The Noah’s Ark story wouldn’t have had as much staying power if the line had been single file.

An Ancient Egyptian hieroglyph meaning “pregnancy/birth” (Figure 4) employs a substantially similar structure to the Hanzi character for “pregnant”: 孕 (Gardiner, 1927) .

![]()

Figure 4. Ancient Egyptian hieroglyph for “woman giving birth.”

Both depictions—Ancient Egyptian and Chinese—show the body of a woman with a child coming out of her conceptual bottom. The Ancient Egyptian character for “pregnant woman” (Figure 5) depicts a woman with a slightly larger stomach, especially as compared with the woman giving birth above (Gardiner, 1927) .

![]()

Figure 5. Ancient Egyptian hieroglyph for “pregnant woman.”

By contrasting two ancient languages—Chinese Hanzi and Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs—one can recognize the universality of a double-lobed shape such as 乃 representing a pregnant female mammal’s body, while at the same time also representing both breasts filled with milk, and female mammal breasts in general.

6. A Pregnant Female Is the Rate-Limiting Step toward Building a Civilization

Farms and harems are both breeding prisons: one male, many females. Both situations allow for the production of abundance. When humans recognized the importance of pregnant female mammals to a tribe’s survival, they used this information pictorially. Ancient depictions of women giving birth have been found in Egypt (Figure 6) (https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-hieroglyph-of-woman-giving-birth-at-the-temple-to-crocodile-god-sobek-21978365.html) and Italy (Figure 7) (https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/713951).

![]()

Figure 6. Ancient Egyptian depiction of a woman giving birth to a child at the temple to Sobek, the crocodile god, at Kom Ombo in Egypt, circa second century BCE.

![]()

Figure 7. Mugello Valley Archeological Project, which oversees the Poggio Colla excavation—a 2700-year-old Etruscan settlement in Italy—found this small fragment of a ceramic vessel which depicts a woman giving birth to a child. This depiction is circa 600 BCE.

Literate humans belong to a fertility culture. We celebrate birth. In the Chinese word for “good” 好, we have the wedding of “female” 女 and “child” 子 together in one character, but their close association conveniently changes the meaning of “female” into “mother” and depicts “mother and child.” Context is everything in Chinese. When “female” (which is anachronistically also used for animals other than human) is next to “child,” the meaning of this character is “good,” ostensibly because everyone knows in a culture which is focused upon fertility, fecundity, and procreation, that “mother” plus “child” is “good” (Figure 8).

![]()

Figure 8. In Hanzi, “good” 好 is composed of two pieces: “female” 女 and “child” 子, which magically turns “female” into “mother.”

The ubiquity of this Chinese character “good” 好 is evident in that it is the “how” in “knee how,” (ni3 hao3) which means “Hello” 你好. Every time Chinese speakers greet each other, they are basically saying, “You mother and child,” which magically turns into “You good.” This phrase has become so commonplace, it is no longer a question. It is assumed you are good. It is assumed that the combo of mother-and-child is good because if fertility weren’t the focus of every successful civilization, those civilizations would not have been successful.

The 120 billion people who have been born on this earth (https://www.prb.org/articles/how-many-people-have-ever-lived-on-earth/) require the existence of a lot of mothers and offspring, which also necessitates an exponentially large amount of sexual intercourse between female and male humans. The image of “mother and child” is more prominent than other images of fertility because society has deemed it more pleasant to see the result of sexual congress than its enactment. Consequently, “Mother + child = good” is a universal motif. This specific duo is found not just in Chinese and the East, but also in the iconography of Isis and Horus of Ancient Egypt (Figure 9) (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/570684), and Mary and Jesus of Christianity (Figure 10) (https://www.flickr.com/photos/adavey/3424334012/).

![]()

Figure 10. Mary and Jesus as depicted on a painting in a 13th century Ethiopian Christian Orthodox church.

For thousands of years we have revered mothers, so it is consistent to see the profile of a pregnant mammal’s body in the structure of “be” 乃, “milk” 奶and “pregnancy” 孕. In fact, there is a similarity of structure in words related to reproduction in other ancient languages. In Ancient Egyptian, the character for “milk” includes double lobes reminiscent of the capital letter “B” rotated 90 degrees counterclockwise. In writing, structure seems to matter more than orientation, and here is a good example. This depiction of “milk” in Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs (Figure 11) most likely shows mammaries, even though Egyptologists characterize a single “mound” as “a loaf” of bread (Gardiner, 1927: p. 27) .

![]()

Figure 11. Ancient Egyptian hieroglyph for “to make milk”; /ir/ means “to make”; the two “loaves” (breasts?) represent the /tt/ sound of “milk.”

The sound /tt/ means “milk” in this word (“ir” means “to make”) and is represented by the double half circles (Gardiner, 1927) . That half circle (the alphabet’s capital “D” rotated 90 degrees counterclockwise) was the sound /t/, which was the feminine ending for all female mammals in Ancient Egyptian (Figure 12) (Gardiner, 1927) . Female humans were conflated with female mammals in written language, which is why I designate “female mammal” as opposed to “female human.”

This female /t/ signifier shows up in Hebrew as well in phrases that reference females, such as “Bat Mitzvah,” which is a female rite of passage, versus the more well-known “Bar Mitzvah” for males. A single /t/ or hump might stand for “female” in Ancient Egyptian and Hebrew, but two “T’s” or two humps seem to stand for reproduction-related words more consistently. Sometimes just doubling the character is enough to suggest breasts, as in the Hanzi word for “tits” 咪咪.

![]()

Figure 12. Male counterparts to female versions lack the /t/ ending (noted in pink) which is represented in Ancient Egyptian by the shape that looks like one breast—although goddesses and princesses get two!—and is used to signify for females, including sows, an animal that cannot make bread but does have teats.

In Hebrew, דד means “nipple.” Words with double “T’s” have a great deal of resonance with female mammaries: “teats” and “tits” in English, tetas in Spanish. In Chinese, the word for “Mrs.” is 太太 (tai4 tai) and it looks like two protrusions. One 太 means “extreme,” so this word is literally “doubly extreme,” which is what the breasts of a wife generally were in a time before birth control. The word 奶奶 (nai3 nai) means “grandmother,” specifically one’s “father’s mother.” Both דד and 太太 appear to emulate female breasts symbolically. On the other hand, 奶奶 is literally “milk milk,” so this suggests “female breasts” in a more conceptual (though still double!) way by orally and semantically acknowledging one’s father’s mother as having nourished two generations (Figure 13).

![]()

Figure 13. The power of two: the same repeated symbol—particularly if those symbols jut out—suggests breasts because breasts come in twos and they hang off the body in a cantilevered way.

In every ancient written language, a special character denotes “female” because females have value due to their procreative nature. There are a variety of ways to signify for “female,” but double “humps” have metaphorically represented “fecundity” for a long time. Four different written languages have double-lobed structures with reproduction associations: Chinese, Ancient Egyptian, Thai, and Sumerian. “Be,” “milk,” “pregnant,” “mother,” and “child” are all the results of sex (Figure 14). Chinese also has the character for “mother” 母 not included here because its orientation is not identical, but one can still see the double boxes, both with dots. The dots could signify for “working breasts” (similar to 太太) because “working breasts” define a “mother.”

![]()

Figure 14. Six representations of four different written languages that depict an aspect of reproduction with a double-lobed structure.

7. Eyes and Breasts Are Both Targets

Symbols are the vehicles that allow the propagation of a culture. A vehicle carries cargo. That cargo can be meaning. The imprinting on the brain of a shape-to-meaning relationship creates a pattern. That pattern emerges from structures that are important to humans. For example, the words related to sight show similarity because most humans have two eyes, so the concept of seeing is represented bilaterally (Figure 15).

![]()

Figure 15. Words for “eye/behold” in six written languages show similarity in that they all depict a face. Six languages, none considered related, yet the concept of seeing is depicted with the same caricatured bilateral symmetry—note the features all bias to the left. Humans are significantly more alike than we realize.

Eyes and breasts are both targets, a dot inside a circle. Humans are drawn to circular targets because they might be full of substance—fluid that could aid our survival in a time of uncertain water resources. The two breasts of our mother as she feeds us from them is the first positive experience an infant has after emergence. The universality of two circles as enticing to humans is impregnated in language because that attraction equated to human survival. Our existence is predicated upon females becoming mammas, and those mammas’ mammaries becoming full of milk; therefore, double-lobed symbols representing motherly shapes are recreated in written language.

In Chinese, the structure of “be” 乃 resembles the alphabet’s capital letter “B”—and this bears analysis, as well as the fact that “B” starts many words related to reproduction, such as “baby,” “breast,” “bosom,” “boob,” “breed,” “bride,” “brood,” “bear,” “beget,” “biology,” “bud,” “birth,” “blossom,” etc. (Figure 16). We can see how Hanzi has a relationship to other ancient languages. Could Chinese and English also have similar structures that share congruent meanings? Symbols are simplified shapes that can conflate multiple meanings. Experts tell us, the letter “A” was also the head of a cow; the letter “G” was a throwing stick. But when they say the letter “B” is a house, they are not realizing that “house” is synonymous with “female mammals” because that is where female mammals were kept because they were valuable. It is not a stretch to think that the capital “B” is a picture of a pregnant female mammal and specifically a female human (the bottom of the “B” is always bigger than the top as a pregnant female human would be). A pregnant female human is two humans in one, therefore, two bulges. It is also not a stretch to think that the letter “B” is a picture of life-giving female mammal breasts, which also come in twos. No matter what, the letter “B”—as second in the alphabet—is all about the number “two.”

![]()

Figure 16. The similarity between “be” 乃 and the alphabet’s capital B is not only one of structure but also one of meaning: reproduction.

The prefix “bi” means “two together,” as in “bicycle,” “bilateral,” “bicentennial,” and “bite.” The prefix “di” means “two apart,” as in “divorce,” “divide,” divvy,” “dialogue. Capital “D” utilizes only one of “B’s” lobes. “D” is half of “B.” “D” is “B” divided into two because “D” is about division. In fact, “D’s” structure is so equivalent to “half” of a whole that “D” is a half of a circle. Right there in the shapes of the letters are clues to the meanings of the words in which they reside: for example, “biology” is “life” because two individuals, in most cases, must come together in order to conceive.

The alphabet, like Chinese Hanzi, can be analyzed structurally for meaning. Using both structure and anthropology together—another “x, y” strategy—one can decode written language for its underlying patterns, patterns conferred upon written language by the human focus on reproduction. These patterns based upon fertility could be harnessed for better vocabulary retention in all languages. In addition, the contribution female mammals have made to human existence and civilization—all the way down to the physical forms of our written scripts—should be recognized.

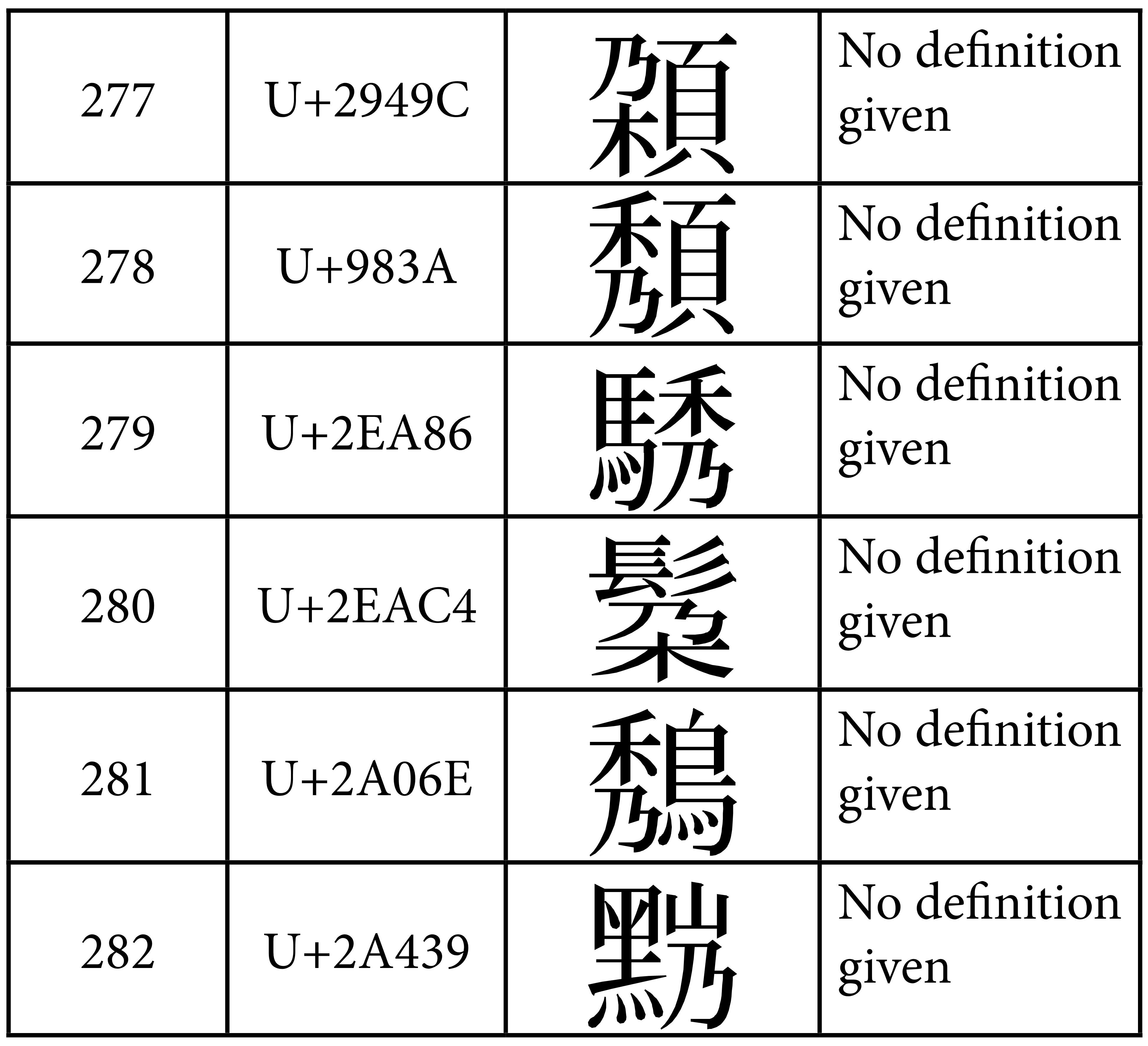

8. The Data

The logical relationship in meaning between words that share a common Hanzi substructure can be seen in the sorted-by-meaning list below of characters containing 乃.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

9. Conclusion

Hanzi Finder, a Hanzi substructure search engine, is a tool that can help analyze the influence that component structures have in determining a Chinese character’s meaning by finding all characters that contain a particular component. Comparing the definitions of characters that have the same components facilitates the clustering of meanings into categories which can serve as prediction tools. Using reproduction as the orienting theme for such categorizations may seem subjective, but considering that replicating is of prime importance to the human animal based upon the eight billion people currently living on this planet, analysis using an anthropological angle seems rational. Recognizing the role that sex and reproduction play in language could be an aid to literacy.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my HanziFinder business partner Chao Xu who helped me make a Hanzi substructure search engine (http://www.HanziFinder.com); my translator and interpreter Maggie Li; the three researchers who helped us redraw the 88,884 characters: Meiqin Xia, Huimin Luo, and Wenqing Huang; and the researcher who handled quality control: Iris Guo. I would like to thank Github for the HanaMinA typeface of 88,884 characters, which we redrew as accurately as possible. I would like to thank Chinese Text Project (https://ctext.org), Chinese Etymology (https://hanziyuan.net/), Wiktionary, KTdict C-E, and Pleco for characters and definitions. I would like to thank Catherine Farris for her “Gender and Grammar in Chinese: With Implications for Language Universals” paper. I would like to thank David Moser for his “Covert Sexism in Chinese” paper and his useful insights on this paper. I would like to thank Dr. Zhenhai Shen, Dr. Yina Sun, Dr. Zhongping Mao, Dr. Siwen Wang, Goodwin Law Firm (especially Flora Zhang and Joel Lehrer), and all my Chinese teachers from Tutoring, Preply, Verbling, and Italki. I would like to thank my daughter Jordan Varney, who is a word person. I would like to thank my son Dalton Varney and his partner Sarah Dahm for their support. I would like to thank my husband Dr. Michael Varney for his continuous support.

Supporting Information

Online:

HanziFinder (https://www.HanziFinder.com)

Chinese Text Project (https://www.ctext.org)

Chinese Etymology (https://hanziyuan.net/)

Wiktionary (https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Wiktionary:Main_Page)

KTdict C-E (iPhone app)

Pleco (iPhone app)

OriginOfAlphabet (https://www.OriginOfAlphabet.com)

Mandarin Online Tools (http://www.mandarintools.com)

Oxford English Dictionary online (OED.com)

Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary (http://psd.museum.upenn.edu)

Hebrew and Greek lexicons (via Strong’s Concordance online)

https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-hieroglyph-of-woman-giving-birth-at-the-temple-to-crocodile-god-sobek-21978365.html

https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/713951

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/570684

https://www.flickr.com/photos/adavey/3424334012/

Printed

Betrò, Maria Carmela. Hieroglyphics, the Writings of Ancient Egypt. New York: Abbeville Press, 1996.

Blank, Hanne. Virgin: the Untouched History. New York: Bloomsbury, 2007.

Borror, Donald J. Dictionary of Word Roots and Combining Forms. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company, 1960, 1988.

Capel, Anne K. (Editor), Glenn Markoe (Editor), Cincinnati Art Museum (Corporate Author), and Brooklyn Museum. Mistress of the House, Mistress of Heaven, Women in Ancient Egypt. Cincinnati: Cincinnati Art Museum, 1996.

Crumb, R., illustrator. The Book of Genesis. USA: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2009.

Dehaene, Stanislas. Reading in the Brain: the science and evolution of a human invention. New York: Viking, 2009.

Diamond, Jared. Why is sex fun?: the evolution of human sexuality. New York: HarperCollins, 1997.

Diringer, David. The Alphabet: A Key to the History of Mankind. USA: Philosophical Library, Inc., 1948.

Fallows, Deborah. Dreaming in Chinese. New York: Walker & Co, 2010.

Fischer, Steven Roger. History of Writing London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2001.

French, Marilyn; foreword by Margaret Atwood. From Eve to Dawn: a History of Women. New York: Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 2008.

Greenberg, Joseph Harold. A New Invitation To Linguistics. New York: Anchor Press, 1977.

Gimbutas, Marija. The Language of the Goddess. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1989 (reprinted 1991).

Hamilton, Sue; Ruth D. Whitehouse; and Katherine I. Wright; editors. Archeology and Women Ancient and Modern Issues. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc, 2007.

Harris, Rivkah. Gender and Aging in Mesopotamia, The Gilgamesh Epic and Other Ancient Literature. Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000. (Red River Books Edition, 2003).

Lakoff, George and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980.

Lefvre, Romana. Rude Hand Gestures of the World. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2011.

Leick, Gwendolyn. Sex & Eroticism in Mesopotamian Literature. London: Routledge, 1994, 2003.

Levy, Howard S. Chinese Footbinding, The History of a Curious Erotic Custom. USA: Bell Publishing Company, a division of Crown Publishers, Inc., 1967.

Lunde, Paul, general editor. The Book of Codes: understanding the world of hidden messages: an illustrated guide to signs, symbols, ciphers, and secret languages. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2009.

Macdonald, Fiona. Women in ancient Egypt. New York: Peter Bedrick Books, 1999.

McNaughton, William and Li Ying. Reading and writing Chinese: a guide to the Chinese writing system, the student’s 1,020 list, the official 2,000 list. Ruttland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle, 1999.

Millett, Kate. Sexual Politics. New York: Ballantine, 1969, 1970.

Mitchell, Stephen and George Guidall (narrator). Gilgamesh [Unabridged Audio CD]. USA: Recorded Books, 2004.

Nissen, Hans J.; Peter Damerow; Robert K. Englund; and translated by Paul Larsen. Archaic Bookkeeping. USA: University of Chicago, 1993.

Pinch, Geraldine. Egyptian Mythology, a guide to Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Pinker, Steven. The Language Instinct: how the mind creates language. New York: Perennial Classics, 2000.

Pomeroy, Sarah B. Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves, Women in Classical Antiquity. New York: Schocken Books, 1975.

Potts, Malcolm and Roger Valentine Short. Ever Since Adam and Eve: the evolution of human sexuality. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Roach, Mary. Bonk, The Curious Coupling of Science and Sex. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008.

Ruhlen, Merritt. A guide to the languages of the world. Volume 1: Classification. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1987, 1991.

Sandison, David. The art of ancient Egypt. San Diego, CA: Laurel Glen Pub., 1997.

Schiff, Stacy. Cleopatra: A Life. New York: Back Bay Books/Little Brown and Co., 2010, 2011.

Schmandt-Besserat, Denise. Before Writing, From Counting to Cuneiform, Vol. I, Texas: University of Texas Press, 1992.

Schmandt-Besserat, Denise. Before Writing, A Catalog of Near Eastern Tokens, Vol. II, Texas: University of Texas Press, 1992

Schmandt-Besserat, Denise and Michael Hays. The History of Counting. New York: Morrow Junior Books, 1997.

Shaw, Ian. The Oxford Guide to Ancient Egypt. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Shlain, Leonard. The Alphabet Versus the Goddess: The Conflict Between Word and Image. New York: Viking, 1998.

Stol, M. Cuneiform Monographs: Birth in Babylonia and the Bible, Its Mediterranean setting. (With a Chapter by F.AM. Wiggermann). Groningen: Styx Publications, 2000.

Valenze, Deborah. Milk. Michigan: Sheridan Books for Yale University Press, 2011.

Yalom, Marilyn. History of the Breast. New York: Alfred A. Knopf: Distributed by Random House, 1997.

Zak, Paul J. The Moral Molecule: The Source of Love and Prosperity. New York: Dutton, 2012.