The Causality of a Political Fragility on Transitional Post-Conflict States in Africa’s Democratization Perspectives ()

1. Introduction

From Africa’s perspective, perceived political transitions are deflective fragilities of post-conflict state traps (Collier, 2020) . The existence of politically disengaged citizens and a fragmented state constantly fuel the vulnerability of state democratization as it is assumed that political transition will transcend efficacy toward transformative and democratic institutions of governance. In this perspective, political transitioning is the pivotal period of settling the fragility traps addressed at the onset of peace treaties. The latest is a post-conflict transition arrangement that permits a fragile state to recover, reconstruct and rehabilitate its social, economic, and political systems (IMF, 2015) .

The interaction between fragility and post-conflict political transitions has varying debates. These debates include countries trapped in cycles of low administrative capacity, political instability, conflict, and weak economic performance by failing to form robust governing systems and institution building (IMF, 2015) . Post-conflict states trapped in fragility have three dimensions of views of statehood to distinguish: the capacity to deliver basic public services; legitimacy to gain recognition from the population being governed; and authority to avert conflict and violence (Collier, 2020) . Therefore, these three dimensions are social cohesions characterizing the functions of a state to withstand its political vulnerability during the political transition. Descriptively, fragility exposes the states’ populations to extreme devastation and obstruction of livelihoods, suppressing the coping capacities of the state, system and mitigation of risks. For instance, OECD (2022) states that “fragile contexts account for a quarter (24%) of the world’s population but three-quarters (73%) of people living in extreme poverty worldwide”. As a result, fragility affects people and their socio-economic prosperity, while post-conflict transition attempts to address social and economic sustainability include a political transition, leading to governance transformation and sustainable peace.

The discourse of political fragility shows expository and correlative views. These views demonstrate that when a state fails its performance at the commencement of its transitioning political roadmap, it fails to maintain its transitioning roadmap, which impairs stability and statehood functional capacity, legitimacy, and authority. Thereafter, the decontextualization of political roadmaps immediately leads to the diversion of the state from the defined political transition, resulting in fragility traps. Acemoglu and Robinson (2021) contend that the fragility trap is reinforced by the “interactions between economic and political instability, poor governance, weak institutional capacity, and lack of political and social inclusion”. The authors’ argument elaborated that political transition is affected by the dominance of weak capacity, legitimacy, and authority to provide citizens with socio-economic resilience and political stability.

Further definition of political fragility is when post-conflict states do not cope with vulnerabilities and responsiveness to shocks from environmental catastrophes affecting socio-economic well-being, security situation, and political economy (Alexander, 2019) . For instance, when the state of fragility has overridden the political stability in a transitioning state, the state quickly reverts to political instability leading to health, economic, and social well-being crises and aggravated governance’s inability to withstand a secure, safe, and stable environment (Andrimihaja et al., 2011) . The consequence of political fragility has adverse effects on a state recovering from post-war with the assumption that political transition arrangements will enhance and necessitate the democratization of the governance.

In addition, post-conflict is described as the “period immediately after a conflict is over”; however, a post-conflict state is still fragile (Frère & Wilen, 2015) . The political fragility trap does not stop immediately when the political transition begins or ends because a state is still along the transition continuum of milestones toward sustainable peace. Post-conflict must therefore adapt to the vulnerability shocks and probability events.

Since the political transition in post-conflict state overarching goal is the transformation of social, economic, political, functional and structural dimensions of development, it is imperative to define development (Deléchat et al., 2018) . Development refers to a multi-dimensional process that involves significant changes in social structures, popular attitudes, national institutions, economic growth, reduction of inequality, and eradication of absolute poverty (Leasiwal, 2021) . In relation to development trends, several scholars theorized post-conflict as achieving conflict resolution and settlement from a “protracted civil war” state through transitional governments, NGOs, and international institutions collaboration by stabilizing the political, economic, military, and social structures of the conflict downtrodden (Rapley, 2007) .

In furtherance to Africa’s perspectives, democracy is assumed that its political path steps are strengthened by political liberalization and democratic consolidation. The discourse of political theory would argue that political liberalization transcended from the engagement of disengaged citizens in voicing their socio-economic rights, liberty, and freedom of expression right while democratic consolidation would be an opportunity for citizens to utilize the permitted governance rights to participate in legitimizing the existence of authority and political wills (Meijer et al., 2017) .

However, the democratic perspective required a radical paradigm shift of political power toward resolving conflict in power struggles in non-democratic states (Söderberg & Ohlson, 2003) . The linkage between political transition and the democratic perspective is to transform the weak governance of the fragile state by ensuring that the state goes through the path of good governance centred on the functionalism-structuralism change (Mross, 2019) .

After elaborating on the definition of fragility and political transition, the paper examined how Africa’s political state transitions withstand the temptation of being trapped in fragility. Political transition arrangements are periods of transitory movement to form the statehood ideological and democratic system of governance and improved social, economic, and institutional functions and performance (IMF, 2008) .

Therefore, the paper cross-examined the relevance of the literature review on political fragility and Africa’s democratization perspectives, discussed the political transition in post-conflict states in Africa, the effects of fragility on state transitional performance, and provided a theoretical framework policy, and recommendations.

2. Research Method

The author used literature reviews on the study of political fragility and transition. Scholars’ discourses on the political fragility trap and adversative effects on the political transition and its democratic transformation encompass a broad understanding of the political fragility of a transitioning state (Acemoglu & Robison, 2012) . The fragility and post-conflict are in tandem with each other while political transition combined and acts as social cohesions to the settlement of a fragile transition by fastening conflict resolution through the establishment of a robust governance system, improved socio-economic development, stabilized political stability, and strengthened institutional capacity (Marwan et al., 2016) .

OECD/DAC (2007) asserted that “states are fragile when state structures lack the political will and capacity to provide the basic functions needed for poverty reduction, development, and safeguard the security and human rights of their populations”. OECD defined a fragile state in the context of political structures, capacity to deliver service and reduce poverty, authority to safeguard security, and legitimacy from gaining the population’s trust. Fragility discourse depends on the context and evolving situation of vulnerabilities (Jorn et al., 2012) .

From the perspective of the African political transition for countries emerging from the conflict-affected situation, building a safe, stable, and secure state requires the post-conflict political transition to form a fundamental dimension of statehood encompassing authority, legitimacy, and capacity (Adams et al., 2020) . What failed African political transitions are challenges linked to weak economic, environmental, social, political, security and societal dimensions. Post-conflict states moving through the fragile context must observe the inclusion of functional and structural transformation that meets the development standard and establishment of robust governance, socio-economic development, and security reform (IMF, 2012) .

Many African states are stuck in fragility because of ineffectual performance, severe domestic resource constraints, and high political vulnerability to shocks (Gelbard et al., 2015) . This assertive fragility is featured by political instability and violence, insecure property rights and unenforceable contracts, and corruption conspiring to create poor governance equilibrium (Andrimihaja et al., 2011) . For instance, countries that have reverted to conflict during their political transitions include Somalia, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, Ivory Coast, Nigeria and Libya.

Finally, the literature review briefly discusses social contract and social accountability theories. Examining these theories is to contextualize the relevancy of state formation and stable political transition. The literature discourse indicated that Thomas Hobbes highly contested the theory of Social Contract due to the Principal works Leviathan of 1651. Hobbes debates the social contract theory as the “man’s life in the state of nature” in which man “voluntarily surrendered all their rights and freedoms to some authority by this contract who must command obedience” (Lasker, 2017) . According to Hobbes, the legality of the social contract was for man to have self-preservation and self-protection.

As proposed by Hobbes, the ideology of giving the sovereignty of citizens’ rights and authority freedom discourages individualism, materialism, utilitarianism and absolutism. However, the social contract theory proposed by Hobbes was further challenged by Locke and Rousseau, who dejected that men did not surrender their sovereignty to authority but only sought protection and security, and that authority has no obligation to dictate individual sovereignty. Both Locke and Rousseau see equality as the basis of state formation that permeates a new form of social organization that guarantee rights, liberty and equality from the “general will” (Lasker, 2017) .

The literature discourse linking social contract to political fragility and transition, social contract theory originated from the “state of nature” where human-being was living under the condition of lawlessness with no subdue authority. For instance, human beings lived in anarchy where society was lawless, in which justice and individual sovereignty were besieged by anarchism through the state of nature (Ethic Unwrapped, 2023) . Thus, the state of nature led to the acceptability and foreseeability of social contract theory, where individuals submit voluntarily to the authorities.

Therefore, in a contemporary systemic governance arrangement, social contract theory has become a form of governance contractualism between the citizens and elite-power-holders chosen through an electoral process in which power-holders are entrusted with the legitimacy and authority to govern. Also, in contrast, political fragility actualized state formation through the state of nature, while social contract matched the political transitions where functional and structured governance principles are established (IEP, 2023) .

After discussing social contract theory corresponding to political fragility and transitions, the literature discourse revealed that social contract theory would be applicable in transitioning states where electoral political arrangements are constituted. For example, the citizens have the will to adopt the constitutionalism of their sovereign state and parties in post-conflict transition fully meet the necessity to hold elections on the premise that the principles of governance structures are established (SEP, 2021) . However, when the principles governing the transitioning political allies are not fully completed, in that case, the probability of forming stable governance becomes minimal; thus, the political transition degenerates into fragility (SEP, 2021) .

Furthermore, the review of social accountability theory also broadened the understanding of political transition indicators to successfully implement a robust political transition (Esbern & Signe, 2013) . Accountability is the “obligation of power-holders to account for their actions” by controlling political and financial in government and private corporations (Naher et al., 2020) . Examining social accountability theory in relation to political transition reinforces the significance of social accountability on its procedural dimension for building a robust political transition. It would probably curb political fragility.

The relevance of social accountability is defined as a tool for citizen-driven to state-driven accountability where elites in power seize the opportunity to promote civic engagement by advocating for the electoral arrangement to furnish a transitional democracy through the universal normative and deontological roles for governance (Aston, 2021) . Social accountability, therefore, creates a re-enforcement mechanism for citizens to engage in dialogue with power-holders in the procedures of state transition and constitutionalism consensus building. As a result, social accountability married the bottom-up approach in delivering excellent legitimacy of a defined authority recognition by citizens and elite-power-holders. It would smoothen political transition while guarding off fragility and stagnation.

3. Discussions

The main goal of political transition is to build the capacity of parties in a post-conflict political settlement. The political transition is an assumption for justifying democratization and strengthening conflict resolutions as the preparatory path to transforming deficit governance and political vulnerability shocks (IMF 2020) . Thus, the basis of political fragility in countries emerging from the war that have experienced the violent traps while beginning to restructure and reposition their capacities to identify the potential conflict triggers during the political arrangement is the establishment of political transition. The transitional arrangement provides negotiated political framework opportunities for parties in conflict and the regional and international actors for peace roadmaps visibility (United State Institute of Peace, 2022) . The parties’ increased political capacity also allows the identification of political settlement parameters through the political transition to identify the core interventional measures addressing the issues intensifying the conflict contention.

Quite often conflict interventions through peace agreements become the conduit to adapt to the international standard of sustainable peace, enhancing economic performance and building robust democratic political transition through election arrangements and the transformation of the autocratic systemic parameters that act as the triggers of violence (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2021) . For instance, stakeholders, policy practitioners, civil societies, and regional and international actors intervene through humanitarian assistance and multi-lateral diplomacies to reinforce the fragile political transition.

However, countries in the political transition arrangement can quickly revert to conflict after the collapse of the transition period before the realization of complete democratic transformation, where elections are supposed to be conducted after the agreed period. USIP, 2022 argues that 25 per cent of the countries that have had political transitions reverted to conflict before the realized sustainable transition. This argument explores the challenges restricting any political transition by the parties due to the poor political fragmentation of the agreed political framework opportunities and interventional measures warranting a peaceful transition. The predicaments of political transitions increased the fragility of democracy due to the vulnerabilities of economic crises and poor implementation of transitory measures.

In order to curb political fragility, the stakeholders of the transitioning parties should observe social cohesions of the parameters that will restrict the collapse of a political transition. These risks to political fragility can be guarded by fair redistribution of resources, allowing the revolving citizens’ necessity for democratic transformation, and discouraging the disenfranchised citizens versus elites in power (Meijer et al., 2017) . The conflicting parties in a fragile political transition could circumvent the conflict triggers by building social cohesion, establishing good governance, enhancing social recovery, promoting economic reconstruction and installing infrastructure facilities for delivering services.

Social cohesions act as bridges to building the ladder of a fragile political transition. During the transitioning period, international, national, and regional actors provide a wealth of opportunities that transmit a milestone for the peaceful transit of the parties (Fonseca, 2015) . For instance, social cohesion, such as peace-building, improved social networks, trust-building, and establishing norms, creates a safe environment for forging welfare’s normative and deontological institutions.

Many African political elites assumed that political transition would be smoothened without focusing on social cohesions. Usually, countries fragmentized by violence would require in-depth work on improving social cohesions in order to entwine interconnectedness and healthy transition to avoid reverting to conflict. For example, countries like Libya, South Sudan, DRC, Burundi and Somalia have returned to conflict because of the detachment from strengthening social cohesions, which would have cemented the impaired fabric of a healthy state (Country Profile, 2022) .

Notwithstanding, it is equally imperative that to avoid political fragility, the transitioning state should vigorously build the establishment of sound governance principles such as the constitution-making process, rules of law, accountability, responsiveness, and equity and inclusiveness. Establishing good governance provides and enriches political transition by playing an inclusive democratization of the citizens and elites in power (Guerzowich & Maria, 2020) . It is functionally and structurally observed that political transition that lacks a bottom-up approach in its implementing pillars has the highest probability of a fragility trap. For instance, the political transition that concentrated powers on elites, and the elites focused on power harness, which in-built an in-fight power struggle, which therefore results in violence (Grosjean, 2019) . In addition, lack of governance creates an imbalance between the citizens being governed and the elites in power. In the event of elites focusing on concentrated power and centralized democracy, the power struggle, unfortunately, returns the established political transition into fragility, resulting in conflict and political upheaval.

Therefore, more significantly, a fragile state must ensure that it invests in social recovery—the delivery of basic services; economic reconstruction—the improvement of decent living by creating jobs and employment; and building of physical infrastructure—the provision of facilities such as roads and bridges, telecommunication, electricity, hospital, schools and better housing (Hamza, 2014; Omag, 2012) .

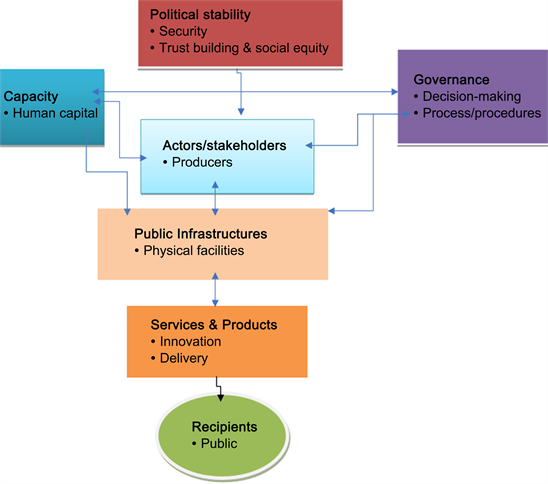

Finally, the discourse of political theories on social contract and social accountability would be the pillows of political transitions in guarding off political fragility through the expedition of transformative leadership in decodifying triggers of political fragility. The state formation through political transition depends on how social contract and social accountability are firmly interwoven in legitimizing recognizable authority. This proposed theoretical framework below demonstrated how political transitions would resolve the fragility trap.

Services Innovation and Delivery Conceptual Framework.

Explanation of the Above Diagram

· Bolstering a robust political stability: has the broad understanding that is a more significant bridge to political fragility and that African countries emerging from war must adapt to ensure that they build robust political stability through security reform, building social cohesion and equity. The stabilized political environment promotes peace and strengthens democracy.

· Accelerating governance principles: people in government play an essential role in the decision-making process and provide norms, rules of law, accountability, and political fragmentation or devolution of powers. Once transitioning state elites provide that space for good governance, it creates a healthy environment for building democratization.

· Strengthening the capacity of human resources: building capable human resources to deliver services and equitable resources distribution has an enormous resourcefulness, ensuring that the systems are managed adequately with efficiency and diligence.

· Building public infrastructures: countries emerging from war have nothing but destroyed or no facilities. Replacing and/or providing new physical assets becomes a method of improving living standards.

4. Summary of the Research Finding

To summarize, the effects of political fragility are numerous when the transitioning states have failed to maintain their agreed political roadmaps. These effects include but are not limited to a vulnerable governance system, disengaged citizens, ineffectual performance, weak institutions, and failed state operations.

5. Recommendation

Further, more research should be considered in the area of fragility and political transition.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, it is an assumption that political transition will always lead to democratization. African countries that have experienced political transitions have become stuck as failed states because of the trap of political fragility. Political transition is only a pathway to finding a functional and structured method of democracy for the fragmented state, which is very difficult in African political transition perspectives to democratization.

The argument elaborated in this paper discusses an in-depth analysis of political transition as the effect of the dominance of weak capacity, legitimacy, and authority to provide citizens with socio-economic resilience and political stability. Nevertheless, what is needed by African countries experiencing political fragility is to have a radical paradigm shift from elite democratic centralism to bottom-up power fragmentation. Elite democratic centralism should be replaced by a broad ideology of bottom-up transition that elevates citizens from the disengaged political discourse toward resolving conflict in state elites’ power struggles with political fragmentization or devolution of power (Söderberg & Ohlson, 2003) .

Acknowledgements

Acknowledged William Tim who recommended some literatures and Janyce Konkin for proofreading the article.