How Leadership Impacts FEMA’s Whole Community Approach during Emergency Management’s Preparedness ()

1. Introduction

Leadership constitutes an essential part of emergency administration during the preparedness phase. It becomes critical during emergencies because it helps effectively manage vulnerabilities and sourcing resources necessary for emergency control. The preparedness process of emergency control involves a constant sequence of planning, structuring, coaching, endowing, conducting trials, assessing, and partaking ineffective solutions (Xiang et al., 2021) . Training and coaching trials form the basis of preparedness in emergency management. It aims towards promptness to address all emergencies and risky incidents.

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) constitutes a body that governs the phases of emergency management to ensure prompt and effective Response (Siedschlag et al., 2021) . FEMA utilizes the whole community emergency approach to control all government levels, enhance individual preparedness for an emergency, and incorporate society as a critical partner in improving security and resiliency. When reacting to emergencies and disasters, the Whole Community strategy engages all government levels with individuals and communities (see Appendix A). It also gives a tactical outline to direct all emergency management members and the community involved and incorporate Whole Community aspects into their activities.

The strategy does not entirely involve an all-focused or encompassing on any particular stage of emergency control or phase of government. Besides, it does not provide specific rigid protocols that prompt emergency managers or communities to follow. Instead, the approach outlines critical ideologies, themes, and trails for activities analyzed from detailed national discussions instigated by FEMA based on practical exercises in everyday life.

Emergency management always involves four stages of practice. They include mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery. However, However, FEMA often focuses majorly on the preparedness stage of disaster management due to its critical role in regulating appropriate practices in the case of an emergency. During this stage, FEMA often focuses on planning and equipping the emergency team with the necessary skills to serve the community best (Walsh, 2019) . The paper, therefore, researches how the whole community leadership approach impacts emergency control during the preparedness phase, the role of FEMA in the process of emergency control, and the effectiveness of the Whole Community strategy in emergency control.

1.1. Problem Statement

Disaster often occurs uneventfully, resulting in significant losses and a slowdown of daily activities (Bhagavathula et al., 2021) . As a result, the community often affected experiences reduced living standards, especially the individuals at risk, such as the homeless, elderly, and the less privileged. Therefore, due to the essence of preparation for sudden emergency events and situations, it became essential to have strategic and efficient leadership that governs the emergency management protocols. Federal Emergency Management Agency has efficiently contributed to successful emergency preparedness and implementation due to effective management strategies. Additionally, the primary role involved exploring the impact of FEMA’s relevance in the whole community emergency strategy (see Appendix B). The problem statement focused further on the significance of whole community strategy in emergency management preparation among the vulnerable members of society who majorly become affected during disasters.

The research’s purpose involved establishing FEMA’s role in the Whole Community Strategy during the preparation stage of emergency control. Emergency management was adopted under the leadership of the Federal Disaster Control Agency in the US. Therefore, the research intended to explore its role in implementing the Whole Community Strategy during the emergency preparation stage. In addition, the research aimed to study the relationship between the Whole Community leadership strategy and the emergency preparation process.

Some of the research goals intended in the study constitute finding out the role of FEMA’s management in preparing for emergencies in the United States. Another plan included analyzing the effectiveness of the Whole Community Strategy in at-risk communities when preparing for disasters and crises. Besides, the research sought to explore the negative impacts of ineffective emergency control leadership. It further analyzed traditional emergency management approaches and the Whole Community Principle.

1.2. Hypothesis

Various research has begun analyzing the emergency management process and the Whole Community approach. Several researchers have developed an interest in the rationality of the Whole Community principle regarding emergency control preparation. Various studies exist on disaster preparation processes, effective response practices, and the government’s role in safeguarding the community from unexpected risks and situations (Spialek & Houston, 2019) . However, a gap exists between the Whole Community process’s leadership structure and emergency control preparation policies.

1.3. Research Questions

1) What role does FEMA play in preparing emergency control practices for at-risk communities?

2) What is the Whole Community Strategy’s effectiveness over traditional strategies in emergency management preparation?

3) What are the effects of ineffective governance during emergency management and preparation?

4) How can the community assist the government in the preparedness phase of emergency control to prevent fatal incidents?

1.4. Hypothesis Questions

H1: FEMA’s leadership structure is essential in emergency management.

H2: The Whole Community Strategy has helped emergency preparedness in at-risk communities.

H3: The Whole Community Strategy is more effective than traditional emergency control practices.

2. Literature Review

Emergency management was established in 1979 after the Federal Emergency Control Agency’s creation. FEMA constitutes five national preparedness goals engaged in various emergency management processes, which merged to form one body (Harris et al., 2018) . The national preparedness goals changed their structure from singly specialized preparedness or closely outlined hazards categories to an all-inclusive hazards strategy and foreign and domestic attacks (see Appendix C). The change illustrates a non-security reduction but an enhanced prominence in making the country’s emergency control ability responsive to any critical emergency.

According to research, emergency management comprises three correlated aspects (Levy & Prizzia, 2018) . The first component includes all category risks. The concept suggests that several collective attributes of natural and technological disasters exist. It indicates that many similar management approaches can relate to all disasters. Another idea includes an emergency control partnership. The emergency control alliance indicates that assembling disaster management resources requires collaboration with all government levels-the, the national, state, resident, and private corporations such as the public, voluntary organizations, and industry and business. The approach also enables the affected communities to provide emergency control solutions. The vulnerable population and emerging leaders can cooperate in such alliances.

The third concept includes the emergency life process. It suggests that disasters and emergencies occur not only once; they happen throughout and have a life process. The cycle becomes characterized by a sequence of control stages: develop approaches to curb disaster, expect and counter emergencies, and recuperate from outcomes. Many nations expect the local authorities to function as emergency preparation managers. Policies outline management programs’ roles and responsibilities and emergency managers at all government levels. Understanding the emergency management structures at all government levels allows for easy coordination of personal preparedness strategies as managers with the official community strategies (Knox et al., 2021) .

Research shows various stages in emergency management (Bhagavathula et al., 2021) . Since the Second World War, emergency administration has concentrated mainly on emergency preparedness. Initially, this constituted planning and getting ready for an unexpected enemy assault. Community preparation for any hazard involves seeking expertise and resources and organizing their application at the onset of disaster. However, other stages of emergency management exist, such as alleviation, preparation, counteraction, and healing.

The first stage in emergency control includes mitigation. According to research, relief prevents potential emergencies or lessens their consequences (Harris et al., 2018) . It involves practices that counteract a disaster, reduce the probability, or minimize the damaging outcomes of inevitable tragedy. For instance, acquiring fire and flood insurance for a home constitutes a mitigation process. Mitigation practices occur beforehand and subsequently of catastrophe.

The next stage of emergency management includes preparedness. It involves grooming to counter a disaster. The preparedness stage involves preparations and plans to protect lives and assist in counter and rescue activities (Bhagavathula et al., 2021) . An example of preparedness includes stocking water and food. Evacuation plans also constitute a form of readiness. Preparedness practices often occur before the onset of a disaster. The third stage in emergency control embraces response. The response comprises activities that safely counteract a catastrophe. The phase includes practices protecting lives and curtailing extensive property destruction during emergencies. Besides, the answer involves setting preparedness goals into practice. Examples of Response include blocking gas pipes in earthquakes and evading tornadoes. Response processes often occur at the onset of a disaster.

The last stage of emergency includes recovery. It involves recuperating from a disaster or emergency. Activities in this stage often constitute actions to resurge to normalcy or safety after an occurrence of a disaster. It may include seeking monetary assistance to cover the necessary conservations. After an event and counteraction of a disaster, a victim’s well-being and safety become determined by their capability to realign their environment and life (Ahmad et al., 2021) .

2.1. The Whole Community Strategy in Emergency Management

According to a public discussion on disaster management, FEMA’s management admitted that the government could prevent and minimize disasters (Craft, 2020) . However, the government-centric strategy for hazard control must sufficiently overcome the challenges of significant devastating events. Therefore, it becomes essential to involve the entire community capacity fully. Thus, the Federal Disaster Control Agency instigated a public dialogue on the essence of the Whole Community Strategy for emergency control. Research shows that many communities have successfully utilized the Whole Community Principle over the years and have gained popularity across the territories and states (Belblidia & Kliebert, 2022) . The public dialogue aimed to enhance shared learning from the societies’ experiences nationwide. It occurred in several areas, including professional conference meetings, research workshops, conference delegations, and official authority sermons.

Research shows that various stakeholders, such as nonprofit sectors, government officials, private sectors, and local communities, have adopted the Whole Community strategy in emergency preparedness (Xiang et al., 2021) . The approach has become incorporated in national emergency agencies such as the National Coordination Frameworks, National Readiness Scheme, and National Preparedness Objectives. FEMA intends to major in research concerning the community action approach to enhance public participation. The Whole Community Strategy equips local communities with emergency management leadership responsibilities in sharing accountability, organizing, and planning to accomplish local emergency control objectives, improving the nation’s resilience and security.

The Whole Community Principle constitutes a tool by which the government officials, community leaders, emergency control specialists, and residents collectively comprehend and analyze the necessities of their corresponding communities and establish the practical techniques to structure and consolidate their interests, capacities, and assets (Bhagavathula et al., 2021) . This approach creates a more efficient channel for community resilience and security. Studies show the approach’s effectiveness in engaging the entire faculty of nonprofit and private sectors, such as businesses, disability organizations, faith-based corporations, and the public, in partnership with the Federal, territorial, state, tribal, and local government agencies.

The structure of the Whole community strategy continuously varies in all disaster settings due to the difference in decision-making in preparation and response processes to hazards and threats (Walsh, 2019) . The main challenge experienced by the emergency management leadership includes comprehending the strategy. Additionally, collectively engaging diverse organizations and groups and the practices and policies that arise from them enhance the capability of at-risk communities to avert, secure, alleviate, counter, and recuperate from all forms of hazards or threats efficiently. Some of the significance of the Whole community constitutes a more detailed, mutual comprehension of society’s dangers, necessities, and abilities. Besides, Whole Community Approach leads to the enhancement of resources through the uplifting of the community to resilience (Knox et al., 2021) .

According to research, a more detailed comprehension of society’s wants and abilities also promotes a more practical application of existing reserves of the community’s capacity or incident constraints (Levy & Prizzia, 2018) . During economic and resource constraints, combining resources and strengths across the entire risk environment helps compensate for monetary burdens for government agencies and various nonprofit and private sector institutes. The fostering and enduring associations to integrate the whole society approach can prove very puzzling; however, its incorporation generates many benefits. The input provides practical outcomes just like the strategy.

Moreover, creating associations and studying a society’s intricacy can reveal interdependencies that may involve bases of unseen vulnerabilities. The stages absorb Whole Community principles during the preparedness phase of emergency control. Such action often eases the process during counteraction and healing due to recognizing associates with existing resources and expertise. Therefore, favorable associates contribute to problem-solving and countering hazards. The Whole Society Principle leads to more efficient results for all capacities and forms of disasters, hence improving resiliency and security nationally (Rice & Jahn, 2020) .

2.2. Whole Community Strategies and Leadership

Various factors influence the flexibility of individuals and efficient disaster control results. Research shows that three notions constitute the basis for launching a Whole Society Strategy for disaster management. The principles include:

1) Comprehend and satisfy the specific wants of the entire community.

Community action can result in a detailed comprehension of society’s diverse and unique wants, including its relationships, networks, community setting, customs, values, and demographics (Ahmad et al., 2021) . A deeper understanding of the community helps establish factual protection and sustaining wants and inspirations to contribute to disaster control-related practices before an event.

2) Empower and involve all areas of society.

Involving the whole population and inspiring local responses often enable stakeholders to prepare before and satisfy the specific wants of a people and fortify the local ability to oversee the outcomes of all hazards and threats. The principle expects all the at-risk communities to form a portion of the emergency control team, involving various community members, community and social service institutions and groups, disability and faith-grounded alliances, nonprofit and private sectors, professional alliances, and academia. Government agencies that do not conventionally have direct contact with emergency control may also form part of the board. When the community engages in realistic discussion, it receives empowerment to ascertain its necessities and the available reserves necessary to address an emergency (Ramsbottom et al., 2018) .

3) Fortify what functions effectively in the population every day.

A Whole Society strategy for structuring population resilience necessitates discovering ways to strengthen and support the networks, assets, and institutions that already function correctly in populations and seek to tackle essential issues to the population regularly. Existing relationships and structures available in the everyday activities of people, organizations, corporations, and families preceding an incident can become empowered and influenced to function efficiently throughout and after the emergency attack. Research shows that there exist six other tactical themes that help to understand the role of the Whole Community strategy in emergency control during the preparation stage (Siedschlag et al., 2021) .

2.3. FEMA’s Strategic Leadership Themes

For an agency like FEMA, resilience can arise from its ability to quickly help communities recover from disasters. Madrigano et al.’s (2017) work has yielded some critical discussions surrounding the aspects that enhance resiliency in agencies like FEMA compared to the traditional emergency preparedness approaches. For example, “resilience is more broadly defined, focuses on the whole community, is relationship-based (vs. plan-based) that places more emphasis on population strengths (vs. vulnerabilities), organizational assets (resources, money, skills, relationships), and sustainable development” (Madrigano et al., 2017: p. 40) . Therefore, the following strategic leadership themes were adopted to meet the organization’s challenges.

1) Comprehend the Community Structure

Societies involve exclusive, complex, and multidimensional structures affected by several interdependencies and factors. They include geography, demographics, approach to reserves, involvement with economic prosperity, political activity, crime, government, and social capital practices like social links and the social interrelation between various institutions and groups. A better comprehension of a population constitutes focusing on its affiliates to explore how social action becomes regularly structured, such as social arrangements, community principles, shared organization and practices, and policy-making processes. Research shows that a critical community analysis helps establish possible sources of new shared activities (Xiang et al., 2021) .

The research conducted by the Houston Section of Human and Health Services (HDHHS) on effective ways of engaging the public shows that effective communication and practices with the local communities majorly aid in understanding their various needs, their emergency threats, and efficient ways of responding to uneventful disasters and threats (Zavaleta et al., 2018) . Craft (2020) further suggested that engaging the community in various activities helps create trusted associations and provides new approaches to emergency preparedness, counteraction, and healing practices. In addition, the HDHHS revealed that information from the public helps to satisfy unmet requirements of the populations at risk and promotes good working relationships with population groups and private sector associates to enhance outreach provisions, communication methods, and preparedness platforms (Rice & Jahn, 2020) .

2) Recognize Community Capabilities and Needs

Understanding particular abilities and necessities constitutes an essential strategy for promoting and supporting local programs. Harris et al. (2018) suggest that the population wants to become outlined on the foundation of the resources available in the region. A population’s wants involve what they require without limiting the general conventional emergency control abilities. Through open and precise discussions, emergency control managers can establish the specific desires of the population and the combined abilities, such as civic, public, or private, that exist to respond to them. Blind engagement in community activities can result in ineffective disaster management practices due to the diverse responsibilities of nonprofit and private sector groups and governments in various communities.

According to Walsh (2019) , there are self-evaluating gadgets to assess a community’s readiness for disasters and threats. One of the tools includes Community Resilience Index. The tool also helps the population to evaluate if a standard functionality point can become sustained after a hazard. The self-evaluation gadget can be utilized in assessing various capacities to stipulate a groundwork evaluation of a population’s hazard resilience. Some suitable accommodations include core facilities and infrastructure, transportation problems, community programs and contracts, mitigation practices, corporate programs, and social structures. The gaps become pinpointed through assessment.

The Population Resilience Index assists in discovering faults that a population may seek to analyze before the next projected disaster occurrence and kindles dialogue among disaster managers within a population, thus enhancing its pliability to an emergency. As a result of the preliminary execution of the Population Resilience Index, the research showed that additional allowance had been offered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) agency to enhance capability in the USA. Additionally, it allows emergency managers to help communities develop emergency management plans (Sandoval & Lanthier, 2021) .

3) Foster Collaboration with Society Leaders

In all societies, various informal and formal managers such as local congress leaders, community directors, other national managers, business or nonprofit leaders, faith or volunteer leaders, and longstanding residents contain essential information. They can enhance a detailed comprehension of the population around them. In addition, the managers can assist in ascertaining programs of interest to the community or which they prefer to join, as individuals may likely have a reception to readiness movements (Bhagavathula et al., 2021) . Besides, it becomes essential to involve the community since they are more likely to comprehend the efficiency of disaster management in their daily activities.

According to research conducted by the Colorado Disaster Preparedness Association (CDPA), promoting associations with society leaders helps to source relevant information on the forms of emergency programs pertinent to the community, the availability of resources locally, and the identification of individuals at higher risk of experiencing disaster fatalities such as the elderly, the less privileged, or the homeless individuals (Craft, 2020) . Emergency-resilient communities constitute the population that works and resolve issues efficiently under normal conditions. According to available abilities to necessities and striving to reinforce the resources, communities can enhance their emergency pliability. Society leaders can further encourage associates to join society emergency management programs and to partake individual readiness protocols for their families and themselves.

Studies show that including social leaders in disaster control training provides an essential platform to contact the individuals since these directors can pass readiness knowledge to their community (Ahmad et al., 2021) . Community leaders can constitute a necessary connection between disaster managers and the community they lead. Emergency groups incorporate their private division associates in routine exercises, withstanding and enhancing their associations with time. Before integrating emergency management programs in the community, it becomes essential to research the community’s ideal communication system, customs, and behaviors to effectively organize its necessities in a disaster: disaster managers and the population gain from creating trusted associations.

4) Build and Maintain Partnerships

Creating associations with international coalitions and partnerships constitutes an effective planning tactic to promote the association of an enormous scope of local society members. The mutual endeavor collects varying abilities to the program. It enables higher prospects of attaining a deal with the Whole community and inspiring others to support and participate in emergency management activities. The essential stage in creating these associations includes determining the shared and mutual desires which form a basis for partnerships of groups (Bhagavathula et al., 2021) . Besides, it becomes essential to withstand the incentives and motivations to collaborate for extended periods while enhancing pliability through enhanced private-public association. Therefore, the Federal Emergency Control Management strives to ensure partnerships between the public and private sectors to improve their objectives.

FEMA strives to promote emergency management resilience through the involvement of corporations nationally. Businesses constitute a significant role in developing community resilience. As corporations seek to understand their practical actions to evade or recover from an emergency or disaster based on their objectives, they must also comprehend their customers’ actions to survive the catastrophe. With employees and clients, corporations will succeed. The current association of corporations in emergency preparedness programs creates opportunities for social and economic flexibility within their society. Research shows that ongoing programs can prolong associations (Belblidia & Kliebert, 2021) . Society projects’ ownership helps promote enhanced progress and involvement prospectively. Besides, incorporating the community through regular resilience-cultivating programs like corporation continuity-linked exercises will promote sustenance during disasters (see Appendix D).

5) Empower Local Action

Understanding that the administration at all ranks cannot control emergencies solely signify the need for communities to participate fully in emergency management programs (Bhagavathula et al., 2021) . Empowering local programs dictates enabling community members to spearhead, not trail-in, recognizing urgencies, shaping support, executing programs, and assessing results. The disaster manager stimulates and plans but does not lead these efforts and conversations. The enduring influence of long-lasting capacity creation can become apparent in a developing array of civic habits and programs among directors and the community that become entrenched in the population’s customs. Due to this, the subject of social capital becomes a critical section of promoting the public to lead and own pliability programs. Besides, the public proprietorship of developments offers an authoritative incentive for withstanding programs and envelopment.

2.4. Organizational Leadership Assessment (OLA)

Organizational Leadership Evaluation involves an assessment tool on the leadership management applied by an organization to improve productivity (Craft, 2020) . It often evaluates the management strengths of an organization and helps in critical decision-making (see Appendix E). OLA has six components:

1) Shares power: OLA promotes governance by empowering associates and sharing a passion.

2) Promotes authenticity; leaders should display realism, acknowledge personal errors and limitations in judgment, ensure open communications, promote honesty and integrity, and avoid becoming judgmental.

3) Adoring individuals. Leaders should value others by respecting teammates, appreciating employees’ efforts, listening to them, and placing subordinates’ interests above theirs.

4) Upgrade people. Organizational leaders should develop teammates according to their chances for advancement, and learning environment, demonstrating appropriate behavioral practices and using their power on others’ behalf.

5) Develop community. Servant leaders should develop community by encouraging and building teammates, enhancing associations, linking with teammates, and collaborating with other organizations.

6) Deliver leadership. Leaders can offer leadership by visualizing the prospect through prudence, encouraging adventurers not to lose hope, and setting clear standards and goals for the team.

3. Methodology

The research involved a quantitative study on the role of FEMA in enhancing the emergency preparedness phase through the Whole Community Strategy. FEMA’s effective leadership and strategic programs form a vital part of the preparation for disaster management in the community. The research used Organizational Leadership Assessment (OLA) instrument to collect data on the practical leadership approach of FEMA during the preparedness stage of emergency management. The survey was dispersed to the director, subordinate, and peer associates of Safeguard Iowa Cooperation (SIP). All the participants constituted the emergency management board.

The study applied the OLA study questionnaire to all the sample participants, comprised of Safeguard Iowa Cooperation, consisting of seven hundred and fifty-two individuals from above two hundred societies and all the economic societies. Approval to perform this research on the individual samples was acquired from SIP. Besides, the model accepted a five percent error rank of positive or negative. Sampling bodies commend a sample capacity of two hundred and fifty-five with a population capacity of seven hundred (Spialek & Houston, 2019) . However, when the population constitutes a minimal number, the investigator should reflect on utilizing the whole population. The survey, therefore, became dispersed to the members of the SIP population.

The data exemplify the relative presence of the Whole Community leadership to correlate disaster preparedness with the apparent efficiency of the disaster control program. The OLA contained sixty items separated into six categories to evaluate Whole Community Strategy’s relative availability and compare the comparative presence of Whole Community Strategic management with the perceived efficiency of the disaster management program.

3.1. Research Design and Rationale

The OLA questionnaire contains a five-object Likert scale survey (Craft, 2020) . Response alternatives varied from five, strongly correspond to one, and vehemently oppose. Means became acquired for all the eighty-one six subscales: exhibit validity, cherish people, shares power, offers leadership, improve people, and shape the community. The study involved an observational quantitative study methodology. The research also involved a positivist theoretical context in identifying relationships between the formerly recorded dependent and independent variables. Study partakers constituted SIP associates from three areas of the United States states-non-profit, private, and public.

The participant’s responses were assessed generally; then comprehensive analysis followed based on the respondents’ role within the association; team member, management, or executive. The data became assessed based on demographic standards such as ethnic origin, years of experience in the association, age and role, nature of the organization, education level, and gender. The OLA survey evaluated the relative sensitivity of Whole Community strategic management and the relative sensitivity of effectiveness with the emergency preparedness phase in the population. When reading the outcomes of the Likert instrument, the steadfastness of effects becomes grounded upon various dynamics, including whether respondents read the inquiries correctly (Craft, 2020) .

The research further utilized Cronbach’s alpha constant to check for the effectiveness of the entire survey and the subscales. Various researchers have used the OLA survey to provide a practical organizational management scale (Knox et al., 2021) . The core results of the research illustrated an eighty-two positive correlation between Whole Community Strategic management and effective disaster preparedness, overall emergency management effectiveness, community trust, and national productivity.

3.2. Populations

The research respondent party comprised about seven hundred and fifty-two people and all associates of a charity group devoted to helping Iowa Corporation and the community in the preparedness disaster management phase. Associates comprised individuals from the population-sector disaster control units, the private section groups dedicated to emergency mitigation, and charity groups that take the forefront in championing the necessities of the population hit by emergencies. Therefore, the sample population was selected from the SIP institution due to a diverse source of information from the personnel handling disaster management from various groups and communities.

3.3. Sample

The sample involved comprised approximately seven hundred and fifty-two associates of SIP Corporation. All the associates were qualified to engage in the study. The association management issued the consent form in writing. Since the research happened through email, the researchers incurred no extra fee for the engagement of all the seven hundred and fifty-two associates.

Sampling and compilation of responses conform to all secrecy necessities, anticipating no opposition to the research process. Besides, since the research utilized email and the internet for conveyance, an applicable approval became improvised within the email. Therefore, the completed questionnaire was redirected to OLA directors for data compilation. After compiling the new data, they were redirected to the research center for the assessment using the SPSS application (Harris et al., 2018) . As a result, the research support board managed a credibility level of 85%, enabling the study to become successful. The analysis tool involved the SPSS application, which helped evaluate responses using the KWH test, Pearson’s correlation, and Spearman’s rho.

3.4. Variables

The fixed variables comprised the core elements of leadership and organizational practice: exhibiting validity, cherishing people, sharing power, offering leadership, improving people, and shaping the community. The dependent or unfixed variables constituted the superficial presence of effective FEMA’s Whole Community strategic management and the external condition of emergency preparedness management influenced by three organizational categories: leadership and team associates from the disaster management groups, leadership and team associates from charity emergency control associations, and leadership and team associates from private branch disaster control corporations, all associates of SIP.

3.5. Data Analysis

To accurately assess the primary hypothesis, Pearson’s association coefficient was applied. The researchers created a bivariate correlation template to identify the OLA subscale results and whether the general OLA results corresponded with the association’s effective tallies. The chosen analysis ranged between applications of nonparametric and parametric inferential mathematical tests for relating the OLA subscale means to respondents’ attributes. T-tests become essential when analyzing two groups’ means with data commonly disseminated, while ANOVAs become essential when analyzing more than two groups’ means. The Mann-Whitney U application helps compare two groups’ means for not typically transmitted data.

On the other hand, the Kruskal-Wallis test becomes essential when analyzing the above two groups’ data but is usually disseminated (Knox et al., 2021) . For example, if the assessed data for normal distribution gave negative results for normality, then the comparison of the mean utilized the Kruskal-Wallis H assessment. The study also conducted a reliability analysis on the whole OLA survey and each attribute. Furthermore, Cronbach’s alpha interior reliability coefficient helped estimate the collected data’s steadiness.

3.6. Results

The K-W h evaluation of the seven leadership attributes indicated higher preference values. The null hypothesis was rejected due to higher p-values of the OLA survey than the confidence interval, meaning the higher significance of the strategic Whole Community leadership on emergency preparedness in the organization. The survey illustrated a link between the perceived presence of Whole Community strategic management and perceived emergency preparedness effectiveness. Top management and the personnel associated with the corporation believed the Whole Community emergency strategy demonstrated efficiency in preparation for disasters (Ramsbottom et al., 2018) . It allows for open inclusion and consultation by the community and local authorities.

The participants also held that FEMA’s strategic leadership readily admits change and prospects even higher standards of institutional efficiency in disaster preparedness. Furthermore, based on the OLA system evaluation of the collected data, the SIP participants also showed personal engagement with the strategic leadership of the Federal Disaster Control Board hence positively promoting the success of the readiness phase of emergency preparedness (Walsh, 2019) .

Additionally, the participants showed their diverse roles in the emergency management board due to the leadership strategy that pulls together stakeholders from various divisions and agencies, such as the public, private, charity, and corporate society, thereby enhancing creativity and resilience (Levy & Prizzia, 2018) . The participants believed their collaboration with the strategic leadership plan enabled them to become highly dynamic in readiness for more prominent forms of disaster. Therefore, they often appreciate their roles when collaborating with the community and other potential stakeholders in disaster management.

Further findings of this survey showed no relevant differences in the expected presence of the Whole Community strategic management by FEMA to education level, organizational experience, age, or gender (Ramsbottom et al., 2018) . Multi-divisional collective associations illustrated effectiveness in disaster control. Therefore, comprehensively preferred and perceived Whole Community strategic management could result in more valuable teamwork and disaster preparedness as it sources the community. In this survey, Whole Community management became valued and perceived similarly by women and men, individuals with varying education standards, age groups, periods of stay in various associations, and institution types.

3.7. Interpretation

According to the survey, including the Whole Community strategy in emergency management leads to adequate preparation for unexpected or significant disasters (Rice & Jahn, 2020) . The participants recorded highly productive results for emergency control agencies that apply this leadership structure. In addition, the leadership structure enables the community and stakeholders from various sectors to participate in emergency preparations. Higher significance became recorded when the emergency management firm used the leadership assessment tool that applied this management approach.

The findings correspond to various research information based on associations that engage in collaborations and multi-sector settings with few direct, authoritative protocols (Sandoval & Lanthier, 2021) . For example, the Whole Community strategic management involves collaborations and partnerships with the population or local communities at risk of disaster attacks. The regional alliances help identify specific emergency issues affecting the community and relevant ways of preparing for disasters.

The new paradigm of management, which involves a multi-sector collaboration of individuals, has enabled public-sector emergency managers to adopt various management strategies from local and national programs (Siedschlag et al., 2021) . The results may have differed some decades ago when FEMA used traditional management styles in preparation for disasters, where this was the only research on the perceived essence of Whole Community strategic management in the emergency preparedness stage by FEMA. Due to the new model for the emergency preparedness process, these results impact the method of selecting an Emergency preparation strategy and influence the planning schemes used for prospective and current emergency management.

Furthermore, the study showed that FEMA governs the emergency management board’s role, providing necessary resources for emergency counteraction. In addition, they were assessing the capacity of vulnerable individuals and sanctioning them, assessing appropriate counteraction strategies, and communicating prospected or current information concerning emergency incidences or programs (Walsh, 2019) . Based on the OLA leadership survey, the correlation between perceived effective management of disasters and emergencies could be gauged by job fulfillment (Spialek & Houston, 2019) . The survey has significance. It has revealed that emergency management stakeholders who employ appropriate strategies create a positive environment for enhanced productivity.

4. Recommendations

Based on the research, it becomes essential to conduct additional explorations on disaster management institutions related to Safeguard Iowa Institution in more varied sectors, primarily since Iowa constitutes less information than the whole nation (Walsh, 2019) . Data from these respondents only came from a section of the entire national population. To have a detailed comprehension of Whole Community management in the preparedness phase of emergency control, it becomes essential to engage in broader research through OLA in other regions and states. The Whole Community management approach in emergency preparedness has become utilized in various multi-sector areas.

Another recommendation suggests that emergency management authorities adopt the Whole Community leadership model in emergency preparation because the readiness for disaster damages depends on the collaboration of associates from all parts of the economy. It becomes essential to have emergency leaders who can spearhead various associated institutions. Research should cover fostering collaborations and partnerships between emergency managers and the community. Besides, researchers should focus on understanding the dynamics of vulnerable communities and formulating special emergency preparedness programs for them (Xiang et al., 2021) . The Whole Community strategic management’s perceived essence showed consistency across the varied population of participants.

5. Conclusion

Adopting the Whole Community model training program or planning program for potential or current emergency management will elevate the preparedness stage of the disaster management paradigm to the next level. Based on the leadership model employed, emergency management can have negative or positive consequences for its constituents. Additionally, progressive emergency management policies and strategies during the preparation stage, such as the effective Whole Community strategy, result in improved emergency counteraction programs such as planning, training, and allocation of resources before disaster attacks (Zavaleta et al., 2018) .

Acknowledgements

I want to express my special appreciation to my committee member and chair, Dr. Ian A. McAndrew, FRAeS, Dean, Doctoral Programs and Engineering Faculty. I am grateful for Dr. McAndrew’s timeless support in encouraging my research and writing to continue developing as a scientist. In addition, his advice on research and academia has been priceless. I would also like to thank Dr. Ron Martin and Carmit Levin for their enduring support. Also, thanks go to my cousin, Ms. Maria Boston, whom I was recently reunited with after 34 years of separation. Maria’s family sacrifices as a single parent did not go unnoticed, and her academic inputs were invaluable.

Appendix A: FEMA’s Whole Community Approach Stakeholders

Note. National Mitigation Framework Second Edition (2016) . https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-04/National_Mitigation_Framework2nd_june2016.pdf.

Appendix B: FEMA’s Whole Community Approach to Emergency Management

Note. Adapted from Karlyn (2019, April 5) . The Whole Community Approach to Emergency Management. SlideServe. https://www.slideserve.com/karlyn/the-whole-community-approach-to-emergency-management-powerpoint-ppt-presentation.

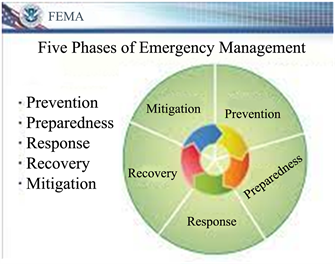

Appendix C: Five Phases of Emergency Management

Note. Adapted from FEMA|Ready My Business (n.d.) . http://www.readymybusiness.com/fema/.

Appendix D: FEMA’s New Strategic Plan

Note. NDPTC—The National Disaster Preparedness Training Center at the University of Hawaii (n.d.) . Retrieved January 22, 2023, from https://ndptc.hawaii.edu/news/2018-2022-fema-strategic-plan/.

Appendix E: Sample Organizational Leadership Assessment

Note. Adapted from Organizational Leadership Assessment (n.d.) . Olagroup.com. https://olagroup.com/Display.asp?Page=servant_leadership.