Gerrymandering Causes Partisan Polarization: A Need for a New Policy ()

1. Gerrymandering Causes Partisan Polarization

In March of 1812, a political cartoon by Gilbert Stuart depicted a forked tongue creature slithering around the state of Massachusetts voting district, referred to as the creature, “Gerrymander”, illustrated in the Boston Gazette (Kamarck, 2018) . Hence, gerrymandering became the term for redistricting political party voting boundaries from Republican Governor Elbridge Gerry, who signed a redistricting plan in his favor which the Republicans drew benefiting their party (Kamarck, 2018) . Thus, gerrymandering can be defined as favoring one party over another by drawing political boundaries in one’s favor. Therefore, political competition is an answer to why partisan polarization exists (Brunell et al., 2016: p. 440) and is considered an independent variable in this literature. And, because of political competition, scholars have been prompted to study and determine whether changes in individual districts over decades have contributed to polarization in the House of Representatives (Carson et al., 2007: p. 885) . However, in a check and balance system of the U.S. Constitution and federalism, gerrymandering stays compliant with the U.S. Constitution, if it does not interfere with the 14th Amendment of discrimination. Amendment 10 and the Supremacy Clause are for state and federal powers to be fair, as a combination of powers divided among the federal and state sovereignties, establishing federal relationships in a Constitutional framework of government that protects the rights of the people. Thereby, scholars are continuing their studies on gerrymandering by asking the research question: Does gerrymandering cause partisan polarization and bias? This literature review is in five parts: 1) the history and definition of gerrymandering; 2) Who draws the lines; 3) Methodologies for empirical evidence with dependent variables; 4) Case studies of variables and comparisons; and 5) Summary.

The U.S. Constitution and federalism exist today because of the division of powers between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government, allowing for a check and balance of each other, even during the redistricting and gerrymandering process. Amendment 10, Article VI, section two, of the U.S. Constitution, provides the definition of federal and state powers that binds judges to the Supremacy Clause in Article VI which binds and works with Amendment 10 allowing for federal law to take precedence over states as intended by the founders. Therefore, the gerrymandering process each state endures through their respected legislators, generated by the President’s approval of the U.S. Census each decade, allows for intergovernmental cooperation that protects the states and federal levels of bias and party control when mapping boundaries (Crane 2022) . “Neither Jew nor Gentile, slave nor free, male or female, for we are all one in Christ Jesus” (The Holy Bible, New King James Version, 1982, Galatians 3: 28). Therefore, we must guard each other worldwide.

2. Independent Variables (IV)

Peer-Reviewed Sources that Represent the Most Prominent Work Done to Date Questioning: Does Gerrymandering Cause Partisan Polarization?

Public behavior trends from observation implications from the U.S. constituency of political climate growth reflect partisan polarization has increased but there is less cooperation in the House of Representatives business at the federal level (Andris et al., 2015) . This peer-reviewed source, prominent in the research that partisan polarization is caused by gerrymandering, follows other sources that have studies and agree upon the same cause-and-effect of the research question. Furthermore, independent variables are a value that establishes a cause and

The dependent variable is the effect. Nevertheless, sources that agree gerrymandering causes partisan polarization as follows:

➢ (Andris, et al. 2015, eol123507) observed that a lack of collaboration when voting and reflecting changes in partisanship over the past 60 years has elevated partisan polarization in House business via gerrymandering.

➢ (Brunell et al., 2016: p. 440) found political competition and incumbency advantage are the major reasons polarization exists.

➢ (Carson, et al., 2007: p. 885) has observed a rise in polarization in Congress due to redistricting.

➢ (DeVault, 2013: p. 207) evaluated that political polarization also exists with institutional control of the redistricting process at state levels which affects political polarization regarding trade liberalization policies is on the rise.

➢ (Guest et al., 2019) found partisan gerrymandering threatens democracy.

➢ (Pyeatt, 2015: p. 651) found that benefits from partisanship associations elevated partisan polarization, a cause of polarization in political parties.

➢ (Ruiz, 2019) found that North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Iowa, Arizona, and Washington State were less democratic based on their locations from qualitative and quantitative data.

➢ (Siliezar, 2022) a tool called “redist” creates nonpartisan plans to encourage legislators to throw out gerrymandered maps and create a nonpartisan plan for legislators and redistricting committees.

➢ (Vlaicu, 2018: p. 597) observed independent variables such as income inequality in political participation when classifying changes that occur from wealth bias versus policy preferences.

Therefore, this literature review reveals that out of nine prominent sources researched on partisan polarization, this information can be replicated on the inherent problem of gerrymandering that causes partisan polarization. Independent variables have increased, refer to the following list:

· Gerrymandering redistricting, who draws the boundaries?

· Political competition.

· Benefits of partisanship associations.

· Institutional control instead of trade liberalization policies causes partisan polarization.

· Income inequality.

· Political participation.

3. Unbiased Dependent Variables (DVs)

DV Survey(s)

Surveys consisting of five questions to present to politicians and the public, via door-to-door, 25 feet away from election entrances on election days, applied to social media websites, and through phone interviews with political officials can be done. The effect (DV) of the survey will be the tool to gather information to find out if gerrymandering causes partisan polarization. The sample size will be determined by the Sample Size Calculator for the confidence interval, or margin of error, which in this study will be (3%) and the confidence level that assures one of how confident the sample sizes will be (10%) of the population sample to be represented (Creative Research Systems, 2012) . For example, this survey will represent a population of 167,051 in a Midwestern city. Ten percent of that population totals 16,705 for surveys to be conducted with a margin of error at three percent. (SurveyMonkey, 2022) can act as a web collector absorbing multiple responses to a few simple questions via various website links. However, validation of survey locations and assistance is difficult to obtain, the reason why the Excel program is more reliable for statistical analysis for interviews, surveys, and statistical collection of data is that they are from private or public donors for downloads at a cost on IBM or other software packages to provide statistical data. For example, questions for a survey to the public: Do you know what gerrymandering is? Do you know our legislators draw boundary lines that may favor their party to be elected? Are you in favor of a gerrymandering system bias of legislative control or more of an independent non-biased public commission, like a city or community council, with the representation of several occupations, genders, races, and representation of the community in which the boundaries are drawn? And with an excel program or IBM statistical software package, quantitative analysis can prove the validity and significance of the thesis: Gerrymandering causes partisan polarization. In addition, qualitative research of interviews, focus groups, and observations can also prove the thesis with statistical averages by coding themes and averaging respondents’ feedback (Lune & Berg, 2017) .

For example, Table 1 reflects researchers reporting research that gerrymandering causes partisan polarization (PP) and researchers who find no significance that gerrymandering causes partisan polarization:

![]()

Table 1. Authors Who Disagree with the Gerrymandering Process.

Personal Interviews as a DV

Personal interviews by cell phone and face-to-face with party organizational leaders, political research (focusing on observations of subpopulations and their implications), and testing the hypothesis, will illustrate the cause-and-effect in prior studies with correlations in variables that may reverse the cause-and-effect analysis (Firebaugh, 2008: p. 1) .

Research Questions to Be Performed

The survey and research questions to be performed are five: 1) Do you understand the gerrymandering process, who draws the redistricting lines? 2) Is there polarization in partisan collaboration when mapping boundary lines during the gerrymandering process? 3) To prevent bias, should an independent agency or a nonpartisan commission be appointed by the voters for the gerrymandering process versus legislators? 4) Do you agree gerrymandering is conducted by the Republican Party? And 5) Should gerrymandering exist each decade when the U.S. Census Bureau updates population figures? “For whatever you do, work at it with all your heart, as working for the Lord, not for human masters” (Colossians 3:23, NIV).

Methodologies

In court cases, measurements of party differences in state seats in the House and Senate were calculated and proved inadequate during the gerrymandering process (Tapp, 2019: p. 2) . Samuel Wang provides three tests for practical evaluation applications of partisan gerrymandering to provide courts with demonstrated intent and effects of a distribution of popular votes in each district when drawing redistricting lines (Wang, 2016: p. 1263) . Wang concludes mathematical methods can identify state-level imbalances and that the most harm that comes from partisan gerrymandering is representational (Ibid., 370). An example would be Pennsylvania in the congressional 2012 election, Democrats won only five out of 18 congressional House seats but results reflected Democrats won more than half of the statewide votes (Ibid.). Democratic winners were packed into districts where they won an average of 76 percent of the vote and Republicans won an average of 59 percent (Ibid.). Therefore, Wang and Tapp, two more DVs, can provide quantitative data for empirical evidence in research. Thus, total DVs = four.

4. Studies That Address Independent and Dependent Variables

This section within the literature review is a turning point toward case analysis and case comparisons that strengthens the argument that gerrymandering causes partisan polarization and makes it clear, that polarization between parties, no matter what variable is involved, there is a lack of collaboration in the intergovernmental system which should remain unbiased toward party preferences. Nevertheless, this section provides a qualitative research approach versus a quantitative approach as seen with statistical evidence under the heading of Methodology on page nine. Therefore, this literature review qualifies as a quantitative and qualitative research paper when extended with examples of studies and cases.

(Andris et al., 2015) analyzed data on the Congressional roll-call vote from the U.S. House of Representatives and reported that there was a decline in representatives who agreed with the opposite political party on proposed legislation, proving the lack of collaboration when voting and revealing changes in partisanship over the past six decades. The data reflected individuals, when dealing with the gerrymandering process as part of House business, had incentives that persuaded them to collaborate with members of the opposite party proving partisan polarization exists. Along with other independent variables or causes such as political competition, income bias, benefits of partisanship association benefits of partisanship associations, political participation, and institutional control of trade liberalization policies are all causes for the effect of partisan polarization that become mediating variables that strengthen the IV of the gerrymandering process as the single cause. In other words, more IVs result in more empirical proof of partisan polarization and that gerrymandering plays a major IV role.

In the landmark case of 1962, Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S.186, the Supreme Court held that redistricting qualified as a justiciable question under the the14th Amendment and allowed federal courts to hear the Fourteenth Amendment redistricting cases (McDonald, 2009: p. 243) . But plaintiffs must show the purpose and effect of their discrimination claims in all redistricting cases (Ibid.).

Furthermore, Edgar used the scaling method of the Nominal Three-Step Estimation Multidimensional Scaling Tool (NOMINATE) by scientists Poole Rosenthal from the 80s to analyze selected data, such as roll-call voting behavior in congress. He found that the House members in the U.S. Congress that requested recorded votes from 1995-2010 found that votes demanded by the minority party were disproportionately diverse and partisan, making Congress more polarized (Ibid.).

In support of this literature review’s IVs and DVs, another United States Supreme Court Case involving the gerrymandering process was found in Rucho v. Common Cause, No. 18-422, 588 U.S., 2019, Rucho ended partisan gerrymandering maps from state legislators, challenging computer programs that generated thousands of election district maps (Menter, 2021: p. 346) . However, not since Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109, 1986, did the U.S. Supreme Court first decide that gerrymandering was justiciable instead of discrimination against the 14th Amendment in the U.S. Constitution (McDonald, 2009: p. 243) . Plaintiffs now must show the effect and purpose of their discrimination claims in a redistricting plan such as in the cases of the states of Pennsylvania, Texas, and Georgia, when courts decided gerrymandering obstructed voters’ rights and the tabulation of the U.S. Census (Ibid.). Furthermore, researchers can continue their studies by reporting and evaluating court cases that focus on partisanship and unequal representation instead of racial bias. Thus, two more IVs are now introduced in this literature, racial bias, and unequal representation. This data assists scholars to strengthen their arguments about gerrymandering and partisan polarization since the Supreme Court does not have a measurable standard for judicial review of the gerrymandering process. Nevertheless, there is a need for more accountable software to measure unequal representation, even when Congress limits racial and ethnic minorities from being targeted every ten years during the redistricting process (Saxon, 2020: p. 372) .

The peer-reviewed authors to this point in this literature review have all concurred with the support and agreement evidence that gerrymandering causes partisan polarization. But there are those scholars who argued in opposition. Nevertheless, there is agreement that most scholars lack empirical evidence or extensive studies, totaling the independent variable count to eight.

Comparative Analysis of Research Studies Evaluating Little Polarization During the Gerrymandering Process

One example of minimal polarization caused by gerrymandering was cited in the evidence of state legislatures during 2000-2008 which was competitive in the redistricting of states using bipartisan commissioner courts and illustrated little evidence of polarization (Masket et al., 2012: p. 39) . (McCarty et al., 2009, pp. 667-668) reported there was no empirical evidence that gerrymandering caused polarization, even when geographical sizes limited data when there were problems with the NOMINATE scaling tool, which analyzes and measures legislative roll-calling voting behavior and problems during the annual voting records tabulation process.

Therefore, this literature review reveals an increase in the number of cases that prove partisan polarization is caused by the gerrymandering process. An evaluation was placed on methodologies such as DVs, using court cases for comparative analysis in qualitative research, and choosing key IVs (Lijphart, 1971) . Also, attention to the validity or ability to test and measure the research question was evaluated for reliability. “But when He, the spirit of truth comes, He will guide you into all the truth, He will not speak on his own; but only what He hears, and He will tell you what is yet to come” (John 16:13, NIV).

Who Draws the Redistricting Lines During the Gerrymandering Process?

This question develops into a second DV when answered because the cause-and-effect could cause variation and the need to explain changes in observations (King et al., 1994: pp. 175-176) . However, depending on who draws the redistricting lines in individual states in the U.S., the DV could become biased. Nonetheless, Professor Doug Spencer, at the University of Colorado Law School is managing Professor Justin Levitt’s website while Professor Levitt attends government service. This site, hosted by Loyola Law School since 2011, fills a gap of observational implications on the question, “who draws the lines during the gerrymandering process?” Professor Spencer strengthens this literature review with his report and distinctions of various entities that draw boundaries. Spencer’s research revealed that who draws the lines can have a sizeable difference in where the lines are drawn. State lawmakers control most of the states, subject to veto by the Governor, but can be overridden by legislators with a majority vote of two-thirds (Spencer, 2022) . Advisory commissions are appointed by Iowa, Maine, Utah, and Vermont with advising legislators about where those lines should be drawn (Ibid.). “Backup commissions influence redistricting maps before they get to the legislature and have influence after” according to Spencer. States with backup commissions are as follows: Connecticut, Texas, Ohio, Mississippi, Maryland, Oklahoma, Oregon, and Illinois with special backup procedures to draw lines if the legislature does not pass the plan (Ibid.). Arkansas, Ohio, Missouri, New Jersey, Hawaii, Pennsylvania, and Virginia have their districts advised by politician commissions where elected officials are members; Virginia, New Jersey, and Hawaii use politician commissions also for congressional lines (Ibid.). Professor Spencer reports the remaining states of Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Michigan, Montana, New York, and Washington draw federal and state districts limiting elected officials’ participation with the independent commissions. Therefore, with various entities drawing lines, Republicans can dilute Democratic votes and vice versa during the gerrymandering process (Krasno et al., 2019: p. 1162) . Hence the importance of commissions and agencies to be nonpartisan and non-bias when drawing boundary lines during the gerrymandering process.

5. Conclusion

Traditional districting principles (TDP) that measure with respect for political subdivisions and the geographic information system (GIS) can enhance representative communication and legislative response (Bowen, 2014: p. 856) with penalties for violations of TDPs TDP’s. However, these tools are not as strong as the methodologies reported on page seven of this literature review. Thus, continued research in recording data to explain the artisan change in elections, such as the uncontested southern legislative elections since 1967, reflecting an increase in black democrats and white Republicans, question the Voting Rights Act, section (5) that ensures voters’ rights in partisan and racial lines, when drawn, do not discriminate (Forgette & Winkle, 2006) .

By researching prior cases and new ones, empirical evidence can be found to prove one’s hypothesis. Causal inferences or links are seen, for example, in Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993) U.S. Supreme Court landmark case, where the court ruled in a five to four decision that redistricting by race needed strict scrutiny under the 14th Amendment of the Equal Protection Clause and found that white electoral strength was reduced by the majority-minority voting districts, which the courts confirmed that this case was unconstitutional in racial gerrymandering that benefited whites (Spann, 2020: p. 981) . Furthermore, (Herschlag et al., 2020) suggested that a bipartisan panel of retired judges will reduce polarization and instances of cracking and packing that should be identified during the gerrymandering process. The term “packing” means concentrating on the opponent’s supporters in unwinnable districts and spreading one’s supporters evenly to other districts enables slight marginal wins, termed “cracking” which does not work (Puppe & Tasnadi 2009) . Many politicians and reformers suggest that non-partisan or bipartisan redistricting commissions should draw the congressional districts to enable them to become more competitive and less polarized (Karch et al., 2007) . However, (Friedman & Holden 2008: p. 113) report that electoral boundaries are drawn by political parties leaving the process to governors and legislators to conduct every ten years to account for population variances.

Overall, America is protected by the U.S. Constitution which allows federalism to exist. The United Nations Treaties protect human rights, disarmament, and protection of the world’s air space, and land. However, democracy exists for those countries that refuse an autocratic government. For example, in South Korea, the “Korean Constitutional law is discrete on typology and epistemology for legal scholars but adheres to jurisprudence, trade, and diplomatic prestige, with emphasis on educational efforts of scholarship merit” (Kim & Borhanian, 2019) .

Nevertheless, existing metric tests of partisan gerrymandering need to be reformed to provide better measurement relevance to change and debate concepts of partisan gerrymandering. These changes are needed in courts and intergovernmental agencies for voter protection, for example, the Republican party’s majority in the House of Representatives, from the 2012 state elections, revealed that state courts found seven states responsible for cases of racial and partisan gerrymandering while redistricting, allowing false majorities into those redistricted states (Engstrom, 2002: p. 23) . Informing the public about gerrymandering court cases, performing public surveys on the fairness of gerrymandering, and using the news media to educate the public on this topic, from public and voter opinions (McLaughlin et al., 2017) . By closing the gap on the need to evaluate the gerrymandering process, utilizing independent, non-bias commissions for the redistricting process extend the research question of who should be chosen to draw the boundary lines. If they are needed. Thus, this literature review extends the research question into the hypothesis does gerrymandering cause partisan polarization? To: voting boundaries redrawn from the gerrymandering process by independent agencies or commissions reduces partisan polarization by political officials in the legislature. In California’s 2010 redistricting process, control was led by a non-partisan group that experiences non-partisan control during the redistricting process. This group is called, the Committee of California Citizens (Rambo, 2021) . Thus, a resolution to the problem of partisan polarization caused by the gerrymandering process has been proved with court cases and statistical testing methods. Research suggests non-partisan committees should redraw boundary lines.

Appendix A: PLCY-805-Literature Review Findings Worksheet

Topic: Gerrymandering.

Research Question: Does Gerrymandering Cause Partisan Polarization?

Database(s) Searched: Liberty University Libraries, MO House of Representatives.

Keywords: surveys, redistricting, gerrymandering, Supreme Court, and Constitution.

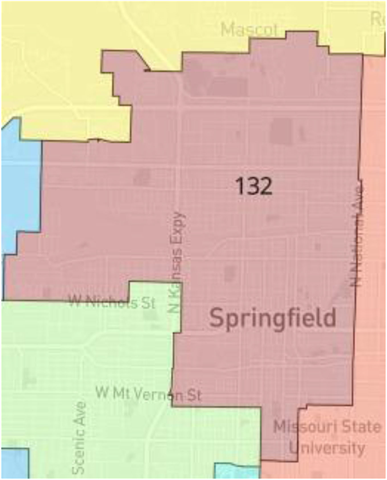

“Friends, (E-mail from Quade to party supporters) It’s been an honor to be able to serve the neighborhoods and parts of Missouri State University in the old 132nd for the past 5 years. Due to redistricting, new boundaries went from 57 percent Democratic performance to 52:”

1) Topic: Gerrymandering Polarization

1

1

Appendix B

1) Topic: Gerrymandering Polarization

2) Research Question: Does gerrymandering Cause Partisan Polarization?

3) Database(s) Searched: Summon-Falwell Liberty Library and Google Scholar

4) Keywords Used in Search: redistricting, gerrymandering, U.S. Constitution

PLCY 804 Literature Review Worksheet Final Paper

2) Research Question: Does Gerrymandering Cause Partisan Polarization?

3) Database(s) Searched: Summon-Falwell Liberty Library and Google Scholar

4) Keywords Used in Search: redistricting, gerrymandering, U. S. Constitution

NOTES

1Author is Missouri Representative, Crystal Quade of the 132nd district. The keywords are election, gerrymandering, and redistricting. Crystal’s email confirms research on declining Democratic Party representation in MO. This independent variable or evidence supports the dependent variables for valid measuring in the Republican controlled gerrymandering process. Therefore, this finding is important.

2V represents variables, I stand for independent, D is dependent, C stands for confirming variables for research because of the findings, and T represents theory that requires variables to confirm research questions or theory.

3V represents variables, I stand for independent, D is dependent, and C stands for confirming variables for research because of the findings, and T represents a theory that requires variables to confirm the research question or theory.