On the Issue of the Achievability of Conceptual Unity in Teaching the Introductory Courses to Journalism/Mass Communication—The Case of the Higher Educational Institutions and Media Schools in Georgia ()

1. Introduction

1.1. Historical Background

As wrote Mark Deuze ( Deuze, 2005: p. 442 ) from Indiana University:

“…worldwide one can find universities, schools and colleges with dedicated departments, research and teaching programs in journalism. The field even has its own international and national journals. This suggests journalism as a discipline and an object of study is based on a consensual body of knowledge, a widely shared understanding of key theories and methods, and an international practice of teaching, learning and researching journalism.”

But we must take into consideration pre-history, namely, the isolationary position of Georgia [Soviet Georgia] from international conventional practice and the western standards. Here, the history of teaching journalism began in Soviet times. In the 60s of the 20th century, the departments of journalism represented a substructure of philological faculties, thus proving that journalism as an academic discipline was considered as belonged to the humanities. Later, academic journalism was formed as an independent faculty only in the sole higher educational institution at that time, the Tbilisi State University. The contingent of applicants was extremely limited and the admission rules differed from the general university rules and procedures, since the general admission exams were preceded by so-called creative contests. This continued until the collapse of the Soviet Union. The introductory course to the profession was predetermined by the ideological mandate of the Soviet regime. Journalism was taught and studied as a kind of Soviet ideological labor, where journalists were professionalized as equated with communist party workers ( Pasti, 2004 ). The introduction to journalism assumed indoctrination in the minds of students of the Leninist principle about the function of journalism as a “collective propagandist, agitator and organizer” ( Gaunt, 1987 ). Later, in post-Soviet Georgia, journalism faculties were opened in other higher educational institutions, which mainly followed the curriculum of Tbilisi State University, taking it as a certain benchmark. These higher educational institutions were either already existing or functioning educational institutions which were changing their profile, or they were newly established universities or higher schools.

Current titles, curricula and institutional statuses of journalism programmes, qualification frame (social sciences) took origins from the middle or late period of 2000s. It is from this period that the regulatory state policy of accreditation of all educational programmes begins in accordance with the Bologna Protocol, that is, in adherence with established procedures and norms. The modern educational system of these and subsequent years followed a global trend that implied intensification of a component of mass communication (so-called Schramm’s line against Pulitzer’s approach in American educational system which later spread onto Europe and aftermath in Post-Soviet Western-oriented countries including Georgia). The emphasis on communication studies, on the one hand, enriched the curriculum, but on the other hand, caused a kind of conceptual chaos due to the breadth of the subject of communication studies. To illustrate this breadth it is enough to mention Denis McQuail’s ( McQuail, 2005 ) theoretical vision and to make acquaintance with the teaching practice in several university programmes in USA and Europe. According to McQuail’s conception, the subject of study of communication is a whole range of issues concerning communication in the broadest sense, history of rise of mass media, characteristic features of media of mass communication, structures, processes, functions and effects of mass communication, links between with mass communication and public opinion. In teaching practice, some curricula include teaching and studying of print media, broadcast media, phonograms, films, recording, radio, graphics, drama, animation, photography, journalism, public relations, advertising, internet media, political communication and self-expression. It was the very circumstance that gave rise to the incentive to research what challenges the mass communication component poses to journalistic education ( Deuze, 2006: p. 20 ).

1.2. Theoretical Background

In the theoretical field, our main task was to trace, on the basis of particular examples, what meaning the concept of “introduction” acquires in terms of content and methodology. The question arises about the essence of course: is an introduction a certain portion of knowledge, a preliminary treatise or course of study that foreshadows the main part, or introduction is an independent academic content which is or could be so far similar to other courses in the profession, as it refers to the same the paradigm?

Definitions from academic dictionaries, thesauruses, encyclopedias of professional terms, instead of clearing answers, in contrast, gave impetus to new questions, such as: for example, what is the difference between an introductory course to a specific field, branch and an introductory course to a specific sub-paradigm of the same field? Or, for example, what components should an introductory course in the profession of a journalist consist of, if both the name of the programme and the accreditation qualification framework combine journalism and mass communication/communication into one construct, considering them as equal concepts by status and nature?

In the case of our study, we used the following operational definition on introductory course: by the introductory course, we mean those training courses at the bachelor’s degree stage that are designed for students of the first semester and their content metaphorizes “the gates of the profession”, “the entrance to the profession”.

At the initial stage of the analysis, which we call theoretical argumentation, we did so-called library research and chose the method of reviewing those theoretical academic sources/handbooks that contained the concept of “introduction” in their name and which for many years were included in the list of mandatory literature indicated in the syllabi of various journalism, media and communication studies programmes of universities worldwide.

Most of them were re-published for more than 4 or 5 editions, so that indicated their relevance in the academic field. Among them were: 1) Mass Communication: An Introduction to the Field ( Farrar, 1988 ); 2) News as it Happens: An Introduction to Journalism ( Lamble, 2016 ); 3) Introduction to Journalism from Tennessee Journalism Series ( Stovall, 2012 ); 4) Introduction to Journalism: Essential techniques and background knowledge ( Rudin & Ibbotson, 2002 ); 5) Media & Culture: An Introduction to Mass Communication ( Campbell, Martin, Fabos, 2017 ); 6) Introduction to Mass Communication: Media Literacy and Culture ( Baran, 2009 ); 7) Converging Media: A New Introduction to Mass Communication ( Pavlik & McIntosh, 2011 ); 8) Media Impact: An Introduction to Mass Media from Wadsworth Series in Mass Communication and Journalism ( Biagi, 2016 ); 9) News (Routledge Introductions to Media and Communications) ( Harrison, 2005 ); 10) An Introduction to Communication Theory ( Stacks et al., 1991 ); 11) Introduction to Communication Studies ( Fiske, 2010 ). And at last we can’t avoid mentioning Denis McQuail’s “McQuail’s Mass Communication Theory” ( McQuail, 2005 ), which despite having not included the notion of “introduction” might be a brilliant guideline for the professors seeking for new themes and frames of teaching.

The analysis of these sources revealed trends that can be classified in two directions:

1) Emphasis on Communiction Concept. Academic literature aimed at strengthening the communication component, is developing in-breadth, capturing and seizing related fields of knowledge, including purely technological innovations. Also one can observe strengthening of reference to media literacy. This expansion and development have several ramifications: one of the ramifications can be tied with Fiske (2010) , the concept that inquiries, on the one hand, communication studies as a process, and, on the other hand, having emphasized the notion of “message”, studies the construction of meaning in the process of communication, logics of encoding and decoding process. Another branch is associated with the name of Denis McQuail, who in his book “McQuail’s Communiction Theory” ( McQuail, 2005 ) paid more attention to the relationship and interdependence of media and society, schools of communication studies, which had an impressive impact on the development of the entire academic discipline, theories that studied both types of medium and types of content, as well as the relationship between mass communication and public opinion, both diachronically and synchronically. For the third branch (it is impossible to single out one author in the rank of pioneer or pathfinder here), the typology and history of the development of set of media themselves, their capabilities for generating content and its transmission, which refer them to the theory of technological determinism, are of priority. The fourth branch can be described as aimed at media literacy, which is the contribution of Stanley Baran. His textbook “Introduction to Mass Communication”, published in 2009, is subtitled as “Media Literature and Culture” ( Baran, 2009 ). A special vision (so-called advocacy worldview) is distinguished by “Introduction” by Farrar (1988) , which discusses specific, even problematic, but essentially progressive aspects of mass communication that facilitate the entry of women or minority representatives into the media industry; also for Farrar, those economic, cultural and political barriers that hinder the free flow of information and ideas are relevant.

2) Emphasis on Journalism Concept. Introductory courses in journalism show a tendency to deepen, theorizing such nuances of professional practice that a decade ago either were not studied at all, or they were only mentioned in one context or another. The trend of deepening gives rise to the emergence of so-called new “varieties” of journalism, although the reasons and grounds for the emergence of these new directions differ from each other both in terms of validity and innovation. Some of these varieties are predetermined either by technology, or by the author’s authority, or the boundaries of interpretation of the factual foundations of journalism (for example, Synergetic Journalism, Constructivist Journalism, Convergence Journalism, etc.).

As already noted above, our goal was to identify with more or less accuracy the essence of the research construct “Introductory courses in the profession”, the necessity and desirability of its inclusion in the curriculum, its content boundaries and methodological approaches in pedagogical practice.

2. Method

18 interviwes-in-depth were conducted, among them 8 interviews with the Heads of Bachalor Programmes in Media/Journalism/Mass Communication and 10 interviews with the professors of this particular introductory course. The most valuable factor was the participation of regional universities. The interviewees were Heads of Programmes and Professors of the Intraductory courses from Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Black Sea International University, David the Restorer University, Akaki Tsereteli Kutaisi State University, Caucasian International University, Gori State University, Shota Rustaveli State University of Theater and Cinema, Technical University of Georgia. Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University was presented by two Bachalor Programmes in Journalism and Mass Communication.

The pattern of an interview combined the questions which need different kind of answers, those which have potential to be reduced to the certain quantitative, measurable and scalable meaning and those which have to be discussed through mere qualitative discussion.

The questionnaires for the both group consisted of the several blocks: mandatory blocks included questions about the Programmes (as name, status, level of institutional independence, years of teaching practice number of the students enrolled, etc.) and questions for collecting data about particular lecteurs, professors of the specific course (name, academic degree, years of teaching, experience, the other courses leading by the same persons, etc.). The questions of the essential blocks varied depending on the status of the respondents. The essential set of questions for the Heads of Programmes consisted of 6 questions, for the professors, 20 questions using the methodology of cross-checking questions and excluding the approach of leading, prompting or clarifying questions.

As far the results of whole survey is anticipiated as monograph, so in the article introduced we are discussing only personal attitude-based analysis with further implications with scaling by two scales (Guttman-type scale and then Likert-type scale). Two groups of “judges” were specially trained for scaling procedures (8 “judges” for Guttman-type scaling and 12 “judges” for Likert-type scaling).

The research question for the article offered examines the attitudes and requirements of the Heads of Programmes to Introductory course.

3. Discussion

The first question addressed to the respondents was formulated in such way:

How can you define your requirements as the manager of educational programmes to the introductory course? Identify your requirements to the course as attitude-oriented statements from 3 to 5. The order of your statements will not be percieved as ordinal priorities.

In result were collected 44 statements. At the first stage of analysis we employ the scale measurement technique by Guttman scale. The choise of Guttman scale as one of the three unidimensional scales was determined by its nature, cumulativeness and hierarchity, giving possibility to experts to distinguish the attitudes as extremely positive or negative about the subject in-hand.

The instruction for scaling was formulated for the judges as follows: the judges had to evaluate each attitude-centered statement according to the evaluative paradigm is, is not, how precise were the judgments expressed in relation to the introductory course to the profession both in terms of content and teaching methods. We excluded filtering procedure of the certain statements even in the case if they would have been considered as inrelevant by the judges (they might be marked as “is not”).

In result, we got nominal scale which needs internal quantitative validation. Due to it we calculated Cronbach’s α. Owing to null variation inside variables, 31 statements were left off the calculation procedure. For these variables, determinants of matrix covariance are zero or equated to zero. It is for this reason that the statistics of the inversion matrix cannot be calculated and the values of these variables are considered as missing system values. For the other variables that have been statistically processed, the α coefficient for a single scale is −.093, which is a low degree of internal validity (see Table 1 below).

As can be seen from the covariance table, in the case of removal of statement 18 (uniform distribution of positive and negative categorizations, 4 “is” and 4 “is not”), the internal validity of the scale increases sharply (see Table 2 below).

The repeated analysis carried out after the removal of statement 18 showed a

![]()

Table 1. Cronbach’s α coefficient for internal validity.

aThe value is negative due to a negative average covariance among items. This violates reliability model assumptions. You may want to check item codings.

![]()

Table 2. Covariance matrix after deleting the statement equal zero.

aThe value is negative due to a negative average covariance among items. This violates reliability model assumptions. You may want to check item codings.

high level of the α coefficient, which caused an increase in the internal validity of the scale to −.803, which is considered a high indicator of internal validity (see Table 3 below). But the same analysis confirmed to us that such a statistical experiment was a purely quantitative, almost mechanical means of achieving the validity of the scale, which ultimately caused the neglect of most attitudes. Extreme categorization on the Guttman scale turned out to be not quite a relevant approach to measuring attitudes.

This conclusion was confirmed by another circumstance as can be seen from the correlation matrix, statements make different contributions to the value of the α coefficient, so we decided that it would be more appropriate to evaluate the attitudes expressed on a Likert-type scale (see Table 4 below).

At the second stage of the analysis, in order to establish the internal validity of the scale, 12 experts joined the statements evaluation process. They were given

![]()

Table 3. Cronbach’s α after filtering statement 18.

aThe value is negative due to a negative average covariance among items. This violates reliability model assumptions. You may want to check item codings.

![]()

Table 4. Correlation matrix after deleting statement 18.

aThe value is negative due to a negative average covariance among items. This violates reliability model assumptions. You may want to check item codings.

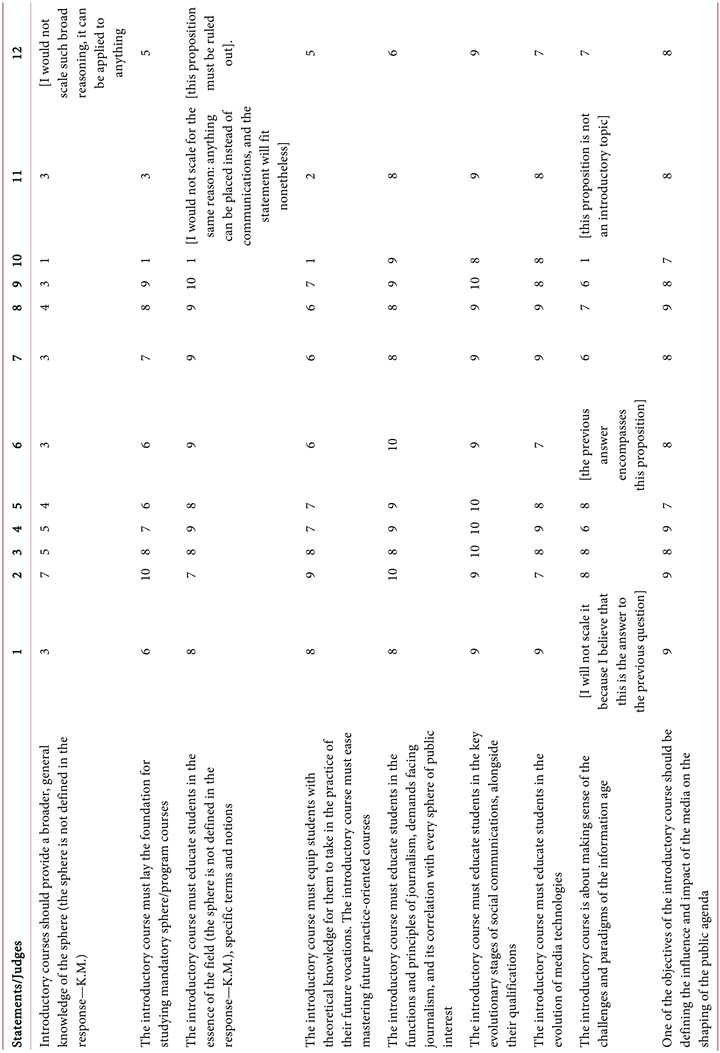

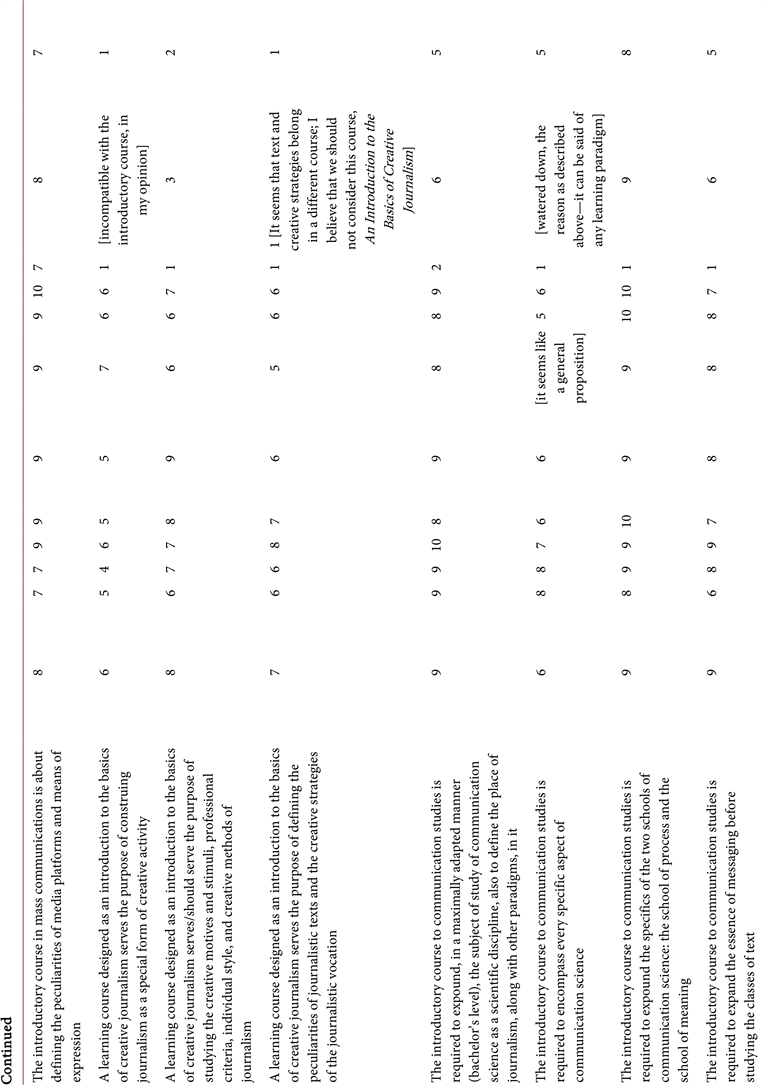

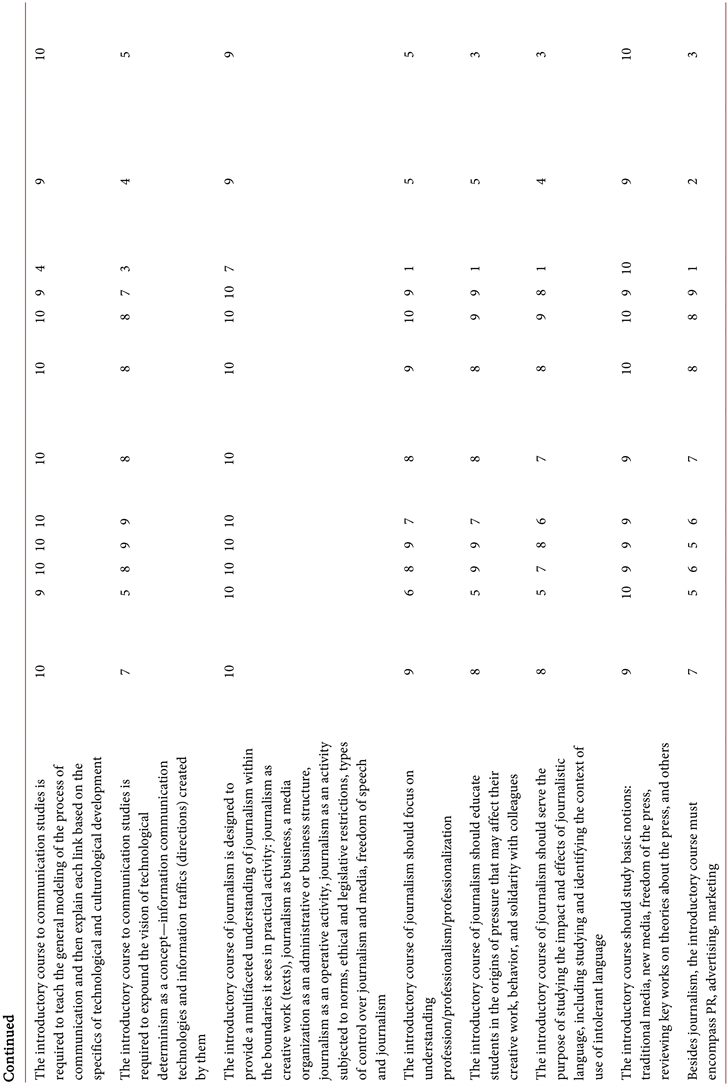

Table 5. Likert-type scaling by “judges”.

the two-step task:

1) To filter irrelevant statements/judgements; irrelevant judgments meant: a) such general or too broad judgments in which key concepts could be replaced with other concepts or another educational paradigm so that the attitude did not lose structure; b) such statement and judgment that did not refer to introductory course’s specifics.

2) On a 10-point scale, to note how the interviwee’s response corresponded to the construct research; on this scale, 1 meant extreme negative, and 10 meant extreme positive. Items from 2 to 9 marked the gradual growth of the attitudes from negative to positive.

In result, “judges” filtered 19 statement having left only 25 ones for evaluation (See Table 5).

One can see that in scaled statements among the numbers are inserted verbally expressed evaluation of validity and relevance. Nevertheless as far as these verbally articulated assessments by their amount didn’t dominated over numbers they were inserted in statistical landscape as grade “0”.

Due to compute internal validity we calculateted Cronbach’s α, which showed the highest level −.962 (see Table 6 below).

As correlation matrix reveals, extraction of any single statement does not increase value of Cronbach’s α. Just extraction of the 8th statement upcomes α to the relatively higher point, to level .966 that is not critical. As for another statements after extraction each of them α’s value just reduces. Thus we can conclude that each statement crucially contributes in entire scale (see Table 7 below).

![]()

Table 6. Cronbach’s α confirms internal validity of the scale.

![]()

Table 7. Correaltion matrix after filtering the statements by Likert-type scaling.

4. Conclusion

The conclusions that follow from the study have several directions:

1) There is no unidimensional answer to the question of how much the introductory course depends or does not depend on other training courses; to what extent it does or does not overlap other professional-related courses.

2) The blurring lines around the concept of communication component and bias to the concept of media and journalism are evident, and it is reflection of cross-paradigmatic nature of curricula (including mission and orientation of journalist education).

3) Even in a small academic community, seemingly with uniform educational traditions, there is no conceptual unity within the introductory course.

4) As for methodological point of view, most likely, introduction is perceived as an umbrella for content and methodology with multiple potential approaches and directions of inquiry depending on the professor’s epistemological and ontological orientations and conceptual frameworks, also tradition of teaching and qualification standards of education policy in a state.