Triage and Risk Concept: Application Proposal for Pre-Hospital Emergencies in a Psychiatric Ambulance in the City of Buenos Aires ()

1. Introduction

In previous publications, we outlined the proposal for a classification system (triage) to be applied in the clinical, social context and under the current ethical-legal standards of our practice for the management of hospital emergencies.

Our hospital is specialized in Mental Health and belongs to the network of health centers of the Government of the City of Buenos Aires, located in the residential neighborhood of Agronomía. Its organizational structure and specificity make it unique in Argentina (and in Latin America) since it focuses on psychiatric emergency care.

Although in its beginnings it was a general hospital, with the restitution of democracy in 1983, it was transformed into a specialized hospital designed exclusively for patients with acute mental illness who require an interdisciplinary approach with the aim of stabilizing their condition quickly and effectively; or failing that, referral to another effector. This position applied to the assistance of patients with mental pathologies since its origin in the 80’s was consistent with the spirit and the postulates of the National Mental Health Law 26,657/10, which in its articles specifies the need for interdisciplinary treatments, with hospitalization times as brief as possible and only in cases of certain and imminent risk the use of hospitalization.

One of the particularities that the hospital has is the work on public roads or other effectors through the psychiatric ambulance. In this, a psychiatrist and the driver attend the locations coordinated by the Emergency Medical Care System to perform psychiatric emergency services. The wide heterogeneity of cases that motivate ambulance interventions makes it difficult to systematize procedures, however, having the guidelines in interventions will generate efficiency in them and reduce the chances of errors due to partial approaches or without a scientific foundation.

The difficulties raised in relation to the systematization of the approaches cause a multiplicity of approach options that can alter their effectiveness, increase response times with the possibility of aggravation of psychopathological symptoms and increase the possibilities of medical error with the consequent associated litigation. For this reason, we consider it necessary and clinically useful for pre-hospital care management in psychiatric ambulances to implement a triage system based on risk assessment of the conditions that prompt assistance.

The objective of this proposed article is to describe a triage proposal to be applied in pre-hospital interventions by the psychiatric ambulance dependent on the Alvear Hospital and under current legal regulations.

2. Materials and Methods

For the realization of this proposal to be applied in the psychiatric ambulance:

1) Global triage models were analyzed as a theoretical framework, which were described in a previous publication by our team [1] .

2) The paradigm under which each triage model was carried out and its possible adaptation to that of our country based on the concept of risk in accordance with the National Mental Health Law 26,657/10 was critically analyzed.

3) Those factors or criteria with possible application for the proposal in the psychiatric ambulance were detected and extracted.

4) Cases of pre-hospital emergency interventions with psychiatric ambulance carried out by psychiatric medical professionals from our “Torcuato de Alvear” Psychiatric Emergency Hospital in the period between January 2018 and December 2021 were randomly studied.

The bibliographic review of triage models published worldwide with high reliability were: the Australian [Australian Triage Scale—ATS and the specific Mental Health Australian Mental Health Triage Scale—AMHTS] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] , Canadian [Canadian Emergency Department Triage & Acuity Scale—CEDT&AS] [7] [8] [9] , Spanish [Sistema Español de Triage-Modelo Andorrano—SET] [10] [11] [12] [13] , Manchester [Manchester Triage System—MTS] [14] and from the USA [Emergency Severy Index—ESI, Pre-Hospital Training Life Support—PHTLS and Advance Training Life Support—ATLS] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] . To access an updated review, a search was performed using the terms “triage”, “emergency” and “psychiatry” or “mental health” or “ambulance”.

The study of pre-hospital emergency interventions with the psychiatric ambulance of our hospital was carried out through the evolutions carried out in the “Ambulance Duty Book”. They were analyzed by 2 psychiatrists with experience in pre-hospital emergencies and a systematization grid was put together to standardize the most prevalent and significant characteristics of clinical presentations, the approach modalities carried out, and the effectiveness of the interventions. Based on these emerging clinical data in the emergency, the construction of a triage for this context began.

The triage proposal included the internationally used criteria related to time, the reason for the intervention, the clinical presentation and the proposed approach modality. Given the pre-hospital context in a psychiatric ambulance, the division into 3 levels was agreed upon and the risk paradigm was taken into account for its preparation in accordance with the National Mental Health Law 26,657/10.

3. Results

For the preparation of the present Mental Health Guard Triage proposal, 3 severity levels were implemented with the colors of the same name as a traffic light, which gives the image of severity or alert in the maximum range of severity.

Three criteria were applied: risk, reason for consultation with clinical presentation, and suggested modality of intervention to be carried out in the pre-hospital context of a psychiatric ambulance [Figure 1].

All the criteria maintained correlation and concatenation with each other based on different clinical presentations of the patients in said context, which, although it is heterogeneous and subjective to each individual and the environment where it is located, the risk-based assessment makes its structuring possible.

The “risk” criterion was divided according to its severity and attentive to Law

![]()

Figure 1. Structure of the proposal triage.

26,657 as well as to the factors that make up the risk (risky condition and vulnerability) in (from highest to lowest risk): certain and imminent for oneself and third parties, true, and without evident or insignificant risk for the last level.

In the criterion “reason for consultation/clinical presentation” the main pictures and their characteristic signology were nominated in a general way and as a guideline to be taken as a framework.

The “intervention modality” criterion was based on interdisciplinary strategies that, according to the evaluation of the team and according to the level, contemplate the application of specific protocols (psychomotor agitation and/or physical and mechanical restraint), the requirement of other effectors (police, firefighters), call an ambulance from a medical clinic when there may be a decompensated basic clinical picture that has psychiatric manifestations and eventual transfer to a general hospital for interdisciplinary evaluation with involuntary hospitalization (level 1) or other strategies.

It was highlighted that, given the significant prevalence of comorbid substance use in patients with mental pathology that can trigger mental illness or in cases of chronic use of substances (at the level of use, abuse or dependence), for level 1 included a clinical and biochemical evaluation for those confusional pictures in order to rule out the toxicological cause, as well as metabolic or other organic causes that could alter clinical and pharmacological interventions. In these cases, it will be necessary to carry out biochemical, electrocardiographic and imaging studies, if necessary, in addition to a complete clinical evaluation.

Figure 2 includes the Triage proposal for pre-hospital emergencies in a psychiatric ambulance.

We believe that in level 1 cases, and according to the assessment of the ambulance psychiatrist or the receiving interdisciplinary team in level 2 cases, they should be addressed by the general practitioner and the studies should be carried out as soon as the treatment ceases risk.

At all levels, a mixed assessment was included in the criterion “reason for consultation/clinical presentation”: both objective and subjective. The objective one included the semiological description of behavioral alterations, while the subjective one is aimed at the evaluation by the professional team of the ability

![]()

Figure 2. Triage proposal for pre-hospital emergencies in a psychiatric ambulance.

to reflect on the problem in which it is found and the recognition of the morbid nature of the behavior.

We emphasize that our triage proposal is not related to the triage models published in terms of the number of levels or the specificity of pre-hospital application in a psychiatric ambulance.

4. Discussion

Triage systems: generalities, proposals and specificities

Triage is a French term applied by the medical sciences to classify, especially in emergency contexts. Triage implies “prioritizing”, “classifying”, “selecting” or “filtering”, which is why it covers different behaviors tending to screen according to clinical needs, possibilities of approach and effectiveness of interventions, as well as organizing resources (material and human ones) in emergency contexts to achieve greater efficiency.

The actions included in the triage seek to direct care and resources towards those individuals who require immediate treatment due to the condition they present and clinical indicators of favorable response based on their clinical status, favoring them over those who suffer from symptoms of less serious or that due to their clinical and evolutionary state will not have benefits with the interventions.

The classification process can be carried out in a hospital or out-of-hospital setting. In both contexts, the same and vital importance is given, they complement and synergize in the cases of health systems with effectors from different levels of care [19] [20] as is our case. In the particularity of our proposal, applying a pre-hospital triage carried out by a psychiatrist who performs her functions in the psychiatric ambulance will enhance and synergize the quality of the interventions.

The principles that support this procedure are the following:

· That the patient receives the level and quality of care according to the risk presented by the clinical picture.

· That the referral hospital be the appropriate one, attentive to the material and human resources necessary to address the patient’s pathology, with less loss of time and resources.

· It supports the bioethical principle of Clinical Justice, whereby clinical efficiency must be based on appropriate care at the right time.

· Facilitate continuity of coordinated assessment and treatment.

· It falls within the legal regulatory framework and the ethical principles of the country of application.

Extra-hospital emergency triage begins with a telephone call to an Emergency Coordination or Regulatory Center, such as 107 or 911 in our City of Buenos Aires. There the urgency is assessed by sending a mobile with the relevant equipment, depending on the waiting time provided to the requirement and type of resource necessary to be used. Once the mobile arrives at home, the health team (driver and doctor) of pre-hospital care will carry out a new classification, being able to resolve the assistance on the spot or request a second on-site evaluation by specialized professionals (in the case of patients with mental disorders who attend a ambulance with a psychiatrist) or decide, based on the degree of complexity assessed, referral to a care center. The destination of the referral is coordinated with the operating table, being in most cases the hospital in the area of the patient’s residence (except in the case of need for specific assistance that exists only in certain centers). Once again at the hospital, the urgency will be reassessed and the procedure will be followed accordingly.

Although triage was generated and implemented in scenarios of massive demand secondary to catastrophes, wars or multiple emergencies, many work groups have applied it and use it in On-Call contexts that due to the increase in demand cannot be responded to for reasons of security, infrastructure or human or material resources. Triage models are generally designed in a classification of 5 levels of different severity that imply different clinical episodes (from mild to severe) and are related to the specification of a maximum clinical response time necessary to be treated, since otherwise the complications can be irreversible or life threatening. Usually colors are established for the 5 severity levels according to the possible delay: red, orange, yellow, green and blue level. This choice of colors is arbitrary and by consensus, its good symbolizes gravity very easily and clearly.

The application of triage in mental pathologies is based not only on the response time, but also on the resources that a device has to respond to them. In the particular case of pre-hospital ambulance emergencies, we consider it useful and that the scenarios (of the pathology and the environment) are propitious for the implementation of this type of strategy. Precisely because of the need for an operative and effective response, we consider the need for a triage based on 3 levels instead of 5, to operationalize its implementation and mindful that acute clinical presentations can be framed and classified in these 3 levels.

From the comparison with the triage models published worldwide, we found no relationship or association with them, given the specificity of the pre-hospital approach to mental pathology by a psychiatrist in an ambulance. In addition, its application is aimed at a technical or general medicine human resource and only two models (MTS and ATSMH) categorize and measure the risk of the condition (and not only strictly for life due to clinical-surgical issues), a concept of vital importance for our legal construct in the urgency that will determine conducts to follow in the case of the voluntary or not of the possible hospitalization. It is noteworthy that only one of the models was adapted for patients with mental pathology (the AMHTS); while the MTS, the CEDT&AS and the SET Andorran Model mention psychiatric symptoms but focus on the reason for consultation and not on the risk that this condition may entail. For these reasons, it is that the comparison of our triage proposal with that of the triage models analyzed would be wrong since their construction frameworks, and especially the means of application, are different and the comparison would generate biased results.

Risk: concept and assessment

One of the fundamental tasks in different fields (clinical care, work, education, forensic) is the prediction of human behavior [21] . The predictive task of being able to see if a person may be at risk and contributes to making clinical decisions with legal impact.

The previous legal paradigm that prevailed in our country was the evaluation of dangerousness (legal term that refers to the possibility, contingency or feasibility of generating or suffering damage that “has support over the existing one, implies “being” and has implications segregation [5] [22] [23] . In some countries, the term dangerousness was changed to “risk of violence” or “dangerous state”, which has no clinical logic or care applicability [24] [25] .

The risk refers to the proximity of damage, being exposed to a harmful event either actively or passively, as well as vulnerability to it, in this case it represents “being” and therefore constitutes an assessment situational according to Law 26,657/10 on Mental Health.

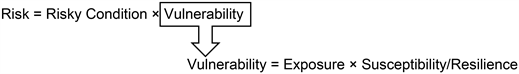

According to the risk theory, risk has components that must be evaluated in the here and now, together with its previous and constitutional issues and factors (modifiable and non-modifiable) [5] . Risk is the combination of the probability that an event will occur and its negative consequences, and is subject to two variables: the risky condition and vulnerability.

For its part, the risky condition is a conduct or condition that can cause injury or some deleterious impact on health or material or other damage. Instead, vulnerability depends on the subjective characteristics of a person and the circumstances that may make him susceptible to harm. It is directly related to the exposure to it and the susceptibility of each person, and inversely with the resilience of the subject.

Expressed in formulas:

The risk assessment must also specify the nature of the hazard and the probability of its occurrence, as well as its frequency or duration, its severity and its consequences. In the same way, it should be taken into account that this is dynamic and contextual, that is, it can vary depending on the circumstances [24] , so it is pertinent to reassess the risk with a certain periodicity to record these possible changes.

There are multiple factors that make evaluations more complex: biological, psychological, and social or environmental. These factors will not be determined in situ given the context of the emergency assisted by a psychiatric ambulance, but they will determine the place of referral of the patient. For example, among the biological factors are neurological and endocrinological alterations and intoxications; the psychological ones are based on defensive and coping mechanisms, and the social ones are linked to the environment or cultural.

Among the factors, they can be divided into risk factors or protective factors. Risk factors are a variable that is positively and directly proportionally related to the certain and imminent risk of a person; protective factors refer to variables negatively linked to the risk situation, that is, inversely proportional to risk.

Together with the assessment, measures must be applied for its management, that is, the actions that are carried out to control a situation, contain or reduce the risk [22] . These management measures can be of 4 types: surveillance, supervision, treatment and planning for the safety of the victim.

The complete risk assessment in pre-hospital psychiatric emergencies by a psychiatrist in a psychiatric ambulance in situ where the behavior takes place in their environment should take into account all the factors described. The implementation of a triage for pre-hospital interventions by the psychiatric ambulance in accordance with current legal regulations will be of clinical utility, in the management of resources and in the prognosis of the condition in the emergency room.

This proposal for a triage system to be used in pre-hospital emergencies with a psychiatric ambulance constitutes a significant contribution since similar proposals have not been described or published. We emphasize that the present proposal in this scientific article arises from the clinical aspects experienced by psychiatric professionals from the only hospital specialized in psychiatric emergencies in Latin America, which also presents the characteristic of performing pre-hospital psychiatric care with a specific ambulance (in its equipment characteristics and professionals who work in it) on public roads, patients’ homes or other institutions (health or not). These described characteristics constitute a limitation for its full implementation in other contexts or health networks as well as institutions, but it allows its adaptation in other contexts depending on the human or material factors available.

5. Conclusions

Mental pathology in emergencies is constantly growing, but its forms and methodologies of approach have not presented innovations to achieve greater effectiveness in interventions. The heterogeneity of the clinical presentations, added to the multiple contexts where it develops, provides a difficulty for the psychiatrist who attends to evaluate emergency cases at the pre-hospital level.

The classification by level of severity is scarce with the use of triage is scarce worldwide for these conditions, and in our country there are no proposals of this type.

We consider very useful the implementation of a triage model for the context of pre-hospital psychiatric emergency with ambulance that is framed in current legislation and in its spirit based on risk assessment.

This type of clinical management interventions will allow greater uniformity, criteria and homogeneity in the professional response, as well as systematize the interventions in order to improve the quality of care.

From the implementation of this proposal, a systematic evaluation every 6 months will be necessary to assess its usefulness in the context of the pre-hospital emergency clinic with a psychiatric ambulance.