Ancestors of Poles in the Battle of the Tollense Valley, Known as the “Pomeranian Troy” ()

1. Introduction

I remember when I read the Andrew Curry’s article about the Colossal Bronze Age Battle appeared in “Science” on 24 March 2016, in which author presented the conclusions of the archaeological research in the Tollense Valley in Western Pomerania.

This topic seemed interesting to me because of the possibility of participation in this battle by the ancestors of the Poles mentioned in that article, which could testify against the allochthonous concept of the Slavs, who allegedly arrived in Central Europe only in the 6th century AD.

I decided to go straight to the discovery site, where I was able to meet Dr. Detlef Jantzen responsible for the work at the archaeological site in the Tollense Valley. After seeing the preliminary results of the research first hand, I decided to write the article from my own perspective based on the data at hand. In the meantime, more media reports and press articles with partial results of the study began to appear, which delayed the work on completing my paper on this subject, because I wanted to include current data.

Finally, at the end of 2022, I prepared the final version, which is an overview of the knowledge about this find and my own view on this matter.

The main purpose of the article is to review the state of knowledge about the Battle of the Tollense Valley and to analyze the available data on this subject in terms of the ethnogenesis of the participants of this war. The secondary goal is to present possible new interpretations of the research results and to discuss the thesis about the possible migration of the Veneti to the north of Europe in this period and the potential armed conflict caused by their influx.

2. Brief Overview and Characteristics of the Discovery

In 1996, an amateur prospector, Ronald Borgwardt, accidentally found a bone with an embedded flint tip in a peat bog near Tollense, but archaeological excavations began on a larger scale only in 2007. Human remains began to be excavated 2.5 km along the Tollense River (Figure 1 and location is on the Map 1). The artifacts discovered by German archaeologists until 2018, including 40 skulls, approx. 13,000 bones of 140 people and 5 horses, also with tipped heads, preserved thanks to the marshy soil, are still a mystery, and researchers are speculating about who and what about he fought, what was the course of this battle like and who won. There are many indications that they were Proto-Slavs from the Lusatian culture. However, most German historians do not yet admit such a thought, believing that the tribes of Lusatian culture were of a pro-German origin, or that the participants in this battle were only representatives of Norse Bronze Age culture.

It is worth noting right away that the Slavic name of the Tollense river is Doleńca (possibly Dolinica, Dolenica, Dolnica, Dolina, Dolinka, Dolincza). It is rather incorrectly reconstructed in Polish as Tołęża (from its current German version—Tollense) or Dołęża (from Polish word “dołęga”—effort), because its name

![]()

Figure 1. Tollense River hiding the secrets of a prehistoric battle. Photo: Thomas Kohler (Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0).

![]()

Map 1. Tollensetal archaeological site in the vicinity of Weltzin on the Tollense River (author: Tomasz J. Kosinski, based on the map created by Ulamm, CC-BY-SA 4.0).

comes simply from the word “dolina” (valley) through which it flows. The Slavic tribe of Dolentians (Polish: Doleńcy, German: Daleminzier, Latin: Daleminci) also lived there, i.e. the inhabitants of the valley. The whole area of the riverside basin, in present-day Mecklenburg, was called the Dolinca (Dolenica) valley, and the lake located there—the Dolinca (Dolenica) Sea (German: Tollensesee). The alternation of T = D in German is the norm, it is enough to quote the name “Thietmar”, also spelled as “Ditmar”.

Battle time 1250-1300 BCE was determined by the radiocarbon method on the basis of research on artifacts found there. The place of the find is about 80 km from today’s Polish-German border in the direction of Świnoujście city (which means: mouth of Swina River). In 1996, an amateur seeker discovered there the first traces of a great battle 3300 years ago, about which historiography is silent, indicating that it is not very reliable. According to the official version of history, at that time this region of Europe was supposed to remain outside the centers of civilization, and the local, rather primitive population was mainly involved in agriculture. Suddenly, it turned out that archaeologists, based on the first research from this site, claim that in this part of Pomerania the greatest battle of antiquity could have taken place, which the Danish archaeologist Prof. Helle Vandkilde from the University of Aarhus, compares it to the Battle of Troy (around 1200 BC), associated with the Hisarlik hill in today’s Turkey ( Curry, 2016 ). This battle is also juxtaposed with the war at Kadesh (today’s Syria) in 1274 BCE on the river Orontes between the Egyptians led by Ramesses II and the Hittites, but more bones and skulls (Figure 2 and Figure 3) were found on Tollense and artifacts than there ( Wojnarowski, 2017 ).

Interestingly, the later famous Retra is also located on Lake of Dolintians (Polish: Jezioro Dolińców or Doleńców, German: Tollensesee), from where the Prilwitz (Slavic: Przylwice—meaning “at lion”) idols I described earlier are supposed to

![]()

Figure 2. A skull found in the Tollense Valley, photo: T. J. Kosinski.

![]()

Figure 3. The skulls found in the Tollense Valley, photo: T. J. Kosinski.

come from ( Kosinski 2017 ; Masch 1771 ), which certainly proves the uniqueness of this area.

In 2013, thanks to geomagnetic surveys of the area, a dyke was discovered on the Tollense, dating back to around 1900 BCE. It is 120 m long and was used to cross the river. It is made of layers of wooden logs covered with sand, reinforced with vertical piles driven into the bottom. A well-frequented trail led to such an advanced, for those times, construction. That is why it was kept in good working order by the local people for centuries, guaranteeing safe passage through water and marshy areas. This peculiar bridge existed at least until that battle (around 1250 BCE). It was through him that the newcomers who were stopped by the locals tried to get through ( Jantzen et al., 2014a, 2011 ).

According to archaeologist Kristian Kristiansen, the battle was to take place in an era of significant upheavals from the Mediterranean to the Baltic Sea. It was around this time that the Mycenaean civilization of ancient Greece collapsed, while the Sea Peoples that devastated the Hittites were defeated in ancient Egypt. Shortly after the Battle of the Tollense Valley, the scattered single farms of northern Europe were replaced by concentrated and heavily fortified settlements ( Curry, 2016 ). Defensive settlements, however, were built as early as the early Bronze Age, an example of which is the settlement in Bruszczewo in south-western Great Poland region (Polish: Wielkopolska), even earlier than the Battle of Tollense. Such fortifications were built for a reason, and they may indicate that smaller or larger scale invasions must have taken place in these areas already in the second millennium BCE.

The vision of a small settlement of the Baltic lands in this period by the peaceful agricultural and pastoral population, however, is stormed by subsequent discoveries, such as those from Tollense. Some believe that the mobilization of such significant forces for this type of war proves the existence of a large political organization in this area. Others believe that there could only have happened occasional self-organization of local tribes in the face of threat.

Preliminary DNA tests of the fallen teeth, carried out by a German-Danish team, revealed genetic material most similar to peoples from southern Europe (probably invaders), from Poland (local defenders) and from Scandinavia (possible mercenaries from one of the parties to the conflict). In an article in “Science” in 2016 it was clearly stated “DNA from teeth suggests some warriors are related to modern southern Europeans and others to people living in modern-day Poland and Scandinavia”. As confirmed by the German archaeogeneticist Joachim Burger from the University of Mainz in a statement for the media. Thus, in the first, spontaneous and non-politicized version that published the results of the research, there were neither Celts nor any Germans (unless we consider the Scandinavians-Normans as such).

There is no historical record of this battle, which means that, properly approaching the topic based on the source method, it did not take place. So it puts helpless historians against the wall. However, the reflections of Wincenty Kadłubek come to mind, deprived of veneration and faith by those historians, who in his “Historia Polonica” describes the history of “ancient Poles” fighting the Danes and Italians ( Güttner-Sporzyński, 2016 ).

The Battle in the Tollense Valley, admittedly, took place long before Rome was founded or before the Scandinavians in the North organized themselves, but it shows a similar dividing line of influence between the same peoples, which lasted for many centuries. The Italo-Celtic population belongs to one linguistic and cultural group. The Scandinavians are also associated with the Germans, although the term “Germania” has a geographic and political character rather than an ethnic one and also includes a Wendo-Slavic substrate.

Importantly, the researchers do not claim that some of the warriors came from the lands of modern Poland, but revealed that the participants in the Battle of the Dolenica (German: Tollense) had DNA similar to modern Poles. It follows that the allegedly “primitive” Slavs did not appear between the Oder and the Elbe until the 6th/7th century AD, thus displacing the “civilized” Germans.

No remains of the ancestors of modern Germans have been found on the Dolenica river, but, as has been mentioned, the ancestors of today’s Poles undoubtedly fought there ( Bogdanowicz, 2016b ). This proves, contrary to the officially accepted allochthonous theory, the continuation of the genetic settlement of the lands west of the Oder by our ancestors since ancient times (over 3250 years ago), which is also confirmed by contemporary genetic and linguistic research conducted by such foreign scientists as Peter Underhill, Giancarlo T. Tomezzoli, Mario Alinei, James P. Mallory, or Anatole Klyosov, as well as Polish ones: Tomasz Grzybowski, Anna Juras, Janusz Piontek. Also, Christian Sell in his 2017 doctoral dissertation, defended at the Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, addresses the topic of the Battle in the Tollense Valley, but does not provide haplogroups (hg) of the samples studied ( Sell, 2017 ). However, on the basis of autosomal DNA analysis, it clearly states that the genes of the ancient warriors from the valley of the Dolenica river (Tollensetal position) are most similar to the genes of modern populations: Poles, Austrians and Scots. The order of these nations is given in the order of their strongest statistical similarity. It follows that Poles are in the first place in genetic compatibility with the participants of this ancient battle. Contrary to Joachim Burger’s statement, Christian Sell assumes that the warriors were more of a local population ( Sell, 2017 ).

The Scottish substrate present there may be associated with the Celts, who are associated with the burial mound culture and are presumably responsible for the decline of the Unietic culture and many other smaller cultures, especially those grouped in the middle Danube basin ( Gedl, 1985 ),. Perhaps the expansion of the “burial mounds” was also supposed to extend to the north, but it was stopped just at the Dolenica by the tribes of the Oder, which formed the Lusatian culture there.

Czesław Białczyński presumes that:

“Perhaps these were the internal settlements of the Proto-Slavic population and the war between the Lusatians and the Mogilans (among which there were Celts), establishing the rule of Mogilevs—later in the records of the Greeks called Mogilans (Mougilones—Mogiła near Krakow, where Wanda and Mogilany Mound near Krakow, several kilometers south of Krak’s Mound and Krakuszowice with the so-called Krak’s Son Mound)—over other Slavs. But it is also possible, and more likely, that the troops that left the archaeological imprint in Górzyca and on the Dołęża River were the Mogilan army sent to the west to guard the territories of the Lusatian and Scandinavian Slavs against Celtic attacks, and then to wage war against the Celts advancing from the west” ( Białczyński, 2016 ).

The founder and administrator of the Eurogenes blog, edited in English, Dawid Wesołowski, known under the nickname “Davidski” also tried to interpret the samples from Weltzin (Polish: Wilczyn). On the basis of the PCA (Principal Component Analysis), he wrote unequivocally that the DNA of the warriors from the Dolenica valley is closest to the Slavs, and in particular to contemporary Poles ( Wesołowski, 2017 ).

Adrian Leszczyński commented on Map 2 as follows:

“The map shows that the warriors from Weltzin are biologically the closest to those contemporary communities that live in the same area where the battle took place and from which the warriors fell there. The greatest similarity concerns the inhabitants of western Poland, Czechs and eastern Germans.

As you know—the inhabitants of eastern Germany and pre-war inhabitants of today’s western Poland are largely Germanized Slavs. Apart from them, there are also non-Germanized Sorbs and Polish indigenous people. The similarity of them and the Czechs to the warriors from Dołęża proves the genetic continuity between the warriors of 1250 BCE and the modern inhabitants of the same lands. It also testifies to the continuity of the residence

![]()

Map 2. Mean results of autosomal similarity between the warriors from Weltzin and contemporary populations (source: http://historycy.org/, forum, author: Lukasz Macuga).

of the lands of the Western Slavic region by the same biological population from at least the second millennium BCE to modern times” ( Leszczyński, 2017 ).

All the above findings and conclusions of various authors completely refute the already compromised allochthonous theory, preached by the supporters of G. Kossinna, K. Godłowski, or his student M. Parczewski and their supporters, about the arrival of this people from the Pripyat region to the area of Odrowiśle in the 7th century AD. However, prof. Parczewski and his ilk keep repeating their false theses on this issue in public discussion, claiming that genetic testing does not explain anything. Either these academics do not understand them, or they simply do not want to accept these facts, because it would also be a painful admission for many years of preaching false views.

Moreover, this discovery may confirm that it was the Proto-Slavs who formed the backbone of the Lusatian culture of that time, encompassing the territories of present-day eastern Germany, the entire territory of Poland, the Czech Republic, part of Slovakia, and reaching as far as Volyn. And this, in turn, agrees with Józef Kostrzewski, who claimed, in spite of the German narrative from the period of partitions, that Biskupin was a pre-Slavic settlement. Who knows if the same should be said about the Lusatian settlement of Buch (Polish: Buk, English: Beech) near Berlin. Let us recall that this professor of merit for Polish science, proclaiming the thesis about the Slavic character of the Lusatian culture, at the same time defended the autochthonous theory of our ancestors ( Kostrzewski, 1923 ).

Until now, it was believed that in the Late Bronze Age, a few primitive, Proto-German tribes inhabited the Baltic Sea. Most of them were to be simple farmers. But Thomas Terberger, a German archaeologist, unequivocally states that these were not farmers, sometimes taking up arms out of necessity, but trained warriors ( Jantzen & Terberger, 2011 ).

This is confirmed, inter alia, by examinations of the skulls, 27% of which have traces of healed head wounds, which suggests that they were warriors experienced in many similar battles. Most of the killed were men in the prime of life, i.e. from 20 to 40 years old, suitable for warfare. The battle was supposed to be short, a day or two, which was found from the unhealed wounds on the remains of ( Flohr et al., 2015 ), which is not so certain as they may have been from the last days of the fight.

Detlef Jantzen, the archaeologist responsible for the site near Weltzin, believes that the locals attacked the merchants, because some of the skeletons indicate that they had deformities resulting, for example, from carrying heavy bags of goods ( Jantzen et al., 2014b ). However, a question arises here, since they came to these areas only for commercial purposes, why are there so many locals killed? The merchants had to be accompanied by a strong armed escort as well as women and children, because even such a few skeletons were found there. Or traders who knew this trail could only be guides of the invaders.

On the other hand, the aforementioned Danish archaeologist Helle Vandkilde points out that the battle was European, and certainly supra-regional. It was an allied army as complex as that described in Homer’s epic of the Battle of Troy, dated some 100 years later ( Vandkilde, 2015 ). It is estimated that about 2000 - 4000 warriors armed with wooden clubs, stone axes, bows, but also bronze knives and swords, which were probably mostly taken from the battlefield by the victors, as valuable trophies at that time ( Curry, 2016 ). The finds also include metal shoulder straps, arrowheads and spearheads, copper ingots, clothes pins, tin, bronze and gold rings and other items ( Lidke, 2015 ; Lidke, Jantzen, & Lorenz, 2017 ).

The lost weapons and ornaments found in the Tollense Valley, according to archaeologists, correspond typologically to the period of the Norse Bronze Culture, which existed between 2200 and 400 BCE. Its range covered the area of northern Germany, Denmark, southern Scandinavia and Gotland as well as other islands in the southern part of the Baltic Sea basin. It is possible that it is a defeated weapon that could not be taken as loot by the victors—the Proto-Slavs, because it fell alone or with the body of the dead into a river or a swamp.

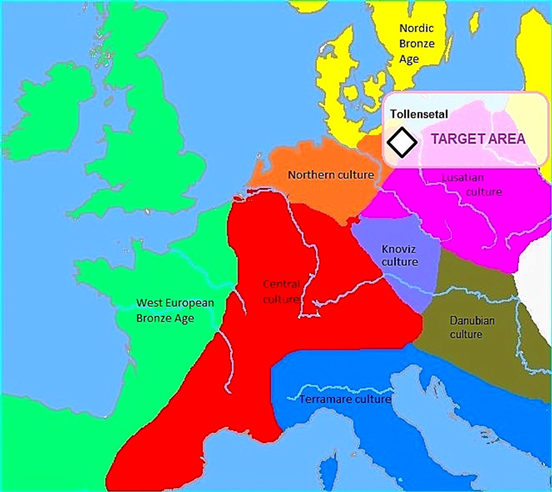

On Map 3, I marked the potential target of this war, i.e. the area it was probably fought over. This is a coastal region, the control of which gave the privilege of profiting from the amber trade along with the use of the Oder and Vistula waterways. Let us remember that not far from Tollensetal, the largest trading post in this part of the world, called Wineta (present Wolin in Poland), was established soon after.

It turns out that the battle took place on the border of three cultural areas, including several related subgroups:

1) Nordic Bronze Age/Northern (Urnfield), specific to the proto-German

Cultures: Lusatian, Nordic Bronze Age, Northern, Knowiz, Danubian, Central, Western European Bronze.

Map 3. Simplified map of European cultures around 1200 BC (prepared by Tomasz J. Kosinski, based on the author’s map: DJ Sturm, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0).

peoples;

2) Central (Urnfield), associated with the proto-Celtic peoples;

3) Lusatian/Knoviz/Danube (Urnfield)—proto-Slavic.

I suppose that the proto-Germans together with the proto-Celts tried to take control of the lucrative Amber Route, but thanks to the support of the Venetian people from the south, the proto-Slavs from the Lusatian culture managed to defeat the invaders and maintain the status quo. It is possible that some of the Veneti settled permanently on the Baltic Sea after this battle, developing trade in various goods, not only amber, establishing further trading posts sending products to the south of Europe, and from there further to Egypt, Greece, the Middle East. If you don’t believe it, you should know that Baltic amber was found, among others, in the tomb of Tutankhamun who reigned from 1333 to 1323 BC ( Usanov, 2022 ). Not by chance in the next millennium, the name Veneti in the form of Wends will be referred to the northern and western Slavs. But more on that in a moment.

According to Professor Kostrzewski’s concept, the Pre-Slavs created a Lusatian culture bordering on the Nordic Bronze culture. Perhaps, then, this conflict arose at the meeting point of both cultures and was a struggle for influence in this area between the Nordics and the Proto-Slavs, and the people from southern Europe were supported by the ancestors of Poles, not the invaders. Especially that the Lusatian culture, due to numerous similarities, belongs to the circle of Urnfield cultures.

However, the above map may suggest that it was the Nordics who expanded their influence on the southern Baltic coast, at the expense of the representatives of the Lusatian culture, perhaps after the victory of the Battle on the Tollense Vallley 150 years earlier.

These and other assumptions may illuminate the exact results of palaeogenetic research, including the haplogroups found in the remains from Weltzin, for publications that German scientists are not very keen on. Moreover, the work on the Tollensetal position was suspended, supposedly for financial reasons, but this decision is overshadowed by various doubts, including attempts to manipulate the research results, which will be discussed later. It is not known whether the draftsmen of this type of maps with the ranges of individual cultures, as presented above, also do not take part in the promotion of a specific historical policy, instead of dealing with facts.

The research on this stand covered only about 500 m2, i.e. about 10% of the area ( Seewald, 2017 ). However, more artifacts have been found than in the fields near Grunwald or other places of great wars known from history. Perhaps the marshy terrain of the valley helped in better preservation of debris and accessories than at other battle sites ( Agnosiewicz, 2016 ). Since the bones of 140 people were found in such a part of the area, there could be more than 1000 dead over the Tollense River, and even several thousand of all participants of the clash. This testifies to the existence of large communities in these areas, and not just clumps of primitive tribes, as academic science has proclaimed so far.

Famous biochemist, also dealing with population genetics, Anatole Klyosov, associated with Harvard University, somewhat confirms my supposition that the victors in this battle were the Slavs who defeated the invaders from the west and north of Europe, perhaps with the support of their related Veneti from the south. Klyosov explains that more samples from R1b found there are due to the fact that the dead were the losers of this battle, and the representatives of R1a—victors, took their dead from the battlefield, in addition to those who did not drown in the swamp and whose few samples were found by archaeogeneticists ( Klyosov, 2017, 2019, 2020 ).

Klyosov also wrote:

“Since these are Slavic territories (Baltic Slavs), the battle was probably between the Erbins (R1b) and the Slavs from the R1a haplogroup (supposedly Lusatian archaeological culture). Then the Slavic Pomeranian culture, haplogroups R1a-L365, was located in the same territories” ( Klyosov, 2017 ).

He adds:

“The clue to who fought whom is provided by DNA genealogy, along with the archeology of ancient cultures. The place of the battle is the area of the early Slavic Lusatian culture, the beginning of which dates back to the same time—3200 years ago. Since the successor of the Lusatian culture, the Pomeranian (Pomeranian) culture had the haplogroup R1a-Z645-Z280-L365, then the Lusatian culture should have had the haplogroup R1a, and the genealogical chain of subclades to it comes from the Fatyanowo culture (4900- 4000 years ago), and there—from the Corded Ware culture, from which the Fatyan culture originated. Here is the string:

R1a-Z280 > CTS1211 > Y35 > CTS3402 > YP237 > YP235 > YP234 > YP238 > L365” ( Klyosov, 2017 ).

Not only ancient DNA (aDNA) and C14 carbon dating, but also isotope tests were carried out. Doug Price, analyzed the isotopes of strontium, oxygen, and carbon in 20 teeth from Tollense and cannot pinpoint exactly who the dead warriors were. He says that “The range of isotope values is really large”, adding “We can argue that the dead came from many different places”. After some ordering of these studies, their results show that we are dealing with two groups, one local and the other newcomers from western or southern Germany, the Czech Republic or Denmark. The lack of results for the ratio of 87Sr/86Sr isotopes above 0.720 indicates that non-local warriors, however, did not come from Scandinavia ( Price et al., 2019 ). So we have another riddle here, as most of the artifacts found belong to the Nordic Bronze Culture, but there are no Scandinavians among the fallen. So maybe there is something wrong with this cultural classification of the finds, or the Nordic bronze culture arose on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea and from there only later spread to the Scandinavian Peninsula. On the basis of studies of nitrogen isotopes in the teeth of the victims, it was also shown that some of the fallen fed on millet, which at that time was rather known in warmer Mediterranean countries, although this cannot be a determinant of location, as grains of this grain were also found in Mecklenburg-Pomerania.

In any case, according to Curry (2016) , from what has been established for today it can be assumed that “the implications will be dramatic”, that is, the history of Europe in that period will have to be rewritten.

3. My Site Vision in Schwerin in 2016

After reading the first articles from 2016 about the Battle in the Tollense Valley, already in the summer of the same year I went by car to north-eastern Germany. I was looking for Slavic traces there (including Prillwitz idols) and of course I also visited archaeologists working on the Tollensetal site.

I got to Schwerin, where, at the nearby castle, Schloss Wiligrad, there is a scientific base, where the remains of the dug up near Weltzin are collected and preserved. I was then able to personally talk about this find with German researchers, including the chief archaeologist responsible for this site, the sympathetic and kind Dr. Detlef Jantzen, who also agreed to make a photo session in his studio (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

![]()

Figure 4. Dr. Detlef Jantzen, head of the German team of archaeologists responsible for the Weltzin site on Tollense River in the research studio in Schwerin in 2016 (photo: T. J. Kosinski).

![]()

Figure 5. The remains and artifacts from the Weltzin site over the Tollense river (photo: T. J. Kosinski).

By the way, it is Dr. Jantzen also showed me the exact place where Prilwitz idols were kept and recommended me to his friend from the Ethnographic Museum in Schwerin, thanks to which I was able to see these artifacts with my own eyes, kept in underground safes. What’s more, thanks to his recommendation, I obtained permission to take pictures of them and to manually review them, about which I wrote the book ( Kosinski, 2018 ).

Scientists working under the supervision of Dr. Jantzen were quite cautious about drawing any conclusions during my visit. They argued that in order to discuss the origin of the participants of the Battle in the Tollense Valley in more detail, one has to wait for the official announcement of the aDNA test results, which, however, the Germans have been delaying for quite a few years. They can turn the academic version of history upside down if they are not distorted, which is possible that not geneticists and archaeologists have been working on for so long, but experts in propaganda, known as historical politics.

Dr. Janzen also complained that they wanted to take his grants from him for this research. He was interested in any financial support, also from Poland. He did not want to talk about the genetic material because he claimed that he was not a geneticist. He also did not understand why none of the Polish institutions and Polish scientists wanted to participate in the archaeological work at this site. With similar finds in Poland, as we know, there is practically always an international team. From what he told me it appeared that so far I was the only person from Poland who was interested in this find at all and had contacted him about it. As it turned out later, the works were stopped soon, on the pretext of the lack of financial resources.

4. New Interpretations of Research Result

The latest theories of German archaeologists researching the Weltzin site speak of two groups, the local—North Germanic (the Poles and Scandinavians mentioned above died somewhere) and the second one, most likely from the area of today’s Czech Republic, i.e. not from the distant south ( Bogdanowicz, 2017 ).

What is very disturbing, in the German media coverage of the Battle in the Tollense Valley, as you can see, there has been no mention of the 2016 revelations for some time. The Scandinavians were made northern Germans, stating that the discovery was evidence that they had lived in these areas as early as 1500 BCE. Nobody officially mentions the ancestors of Poles and peoples from southern Europe anymore. For example, the results of studies with phenotypes (such as the color of skin, hair, eyes, face shape, teeth) have been published, where only the Germanic... warriors from Tollense ( Phenotype SNPs, 2017 ) were ruthlessly mentioned.

Also “National Geographic”, referring to the results of isotope research by J. Burger, writes about the participation of the local population in this battle, i.e. the northern Germans and the invaders from Bohemia. Burger this time emphasizes that he does not see different homogeneous groups and it seems that the battle took place between peoples of the same genetic group, but without giving which one. According to him, it is not particularly spectacular as the original thesis, and even boring, but he cannot help it ( Blakemore, 2019 ).

If we assume that the term “northern Germans” is the Lachs (R1a1) and, to a lesser extent, Old Europeans (I2), and the peoples of Bohemia are the Vends, who may have already mastered these regions, it may turn out that the Lachs and the Venetians have common genetic roots. Then it could be assumed that Enetoi is one of the Sarmatian tribes. Herodotus wrote that they descended from the Scythians. But it can be assumed that it was a geographic and political term (an alliance of various steppe peoples, including representatives of R1a and R1b), rather than an ethnic one. As it is the term “Germans” encompassing the Teutonic, Wendo-Slavic, Sarmatian and partly Celtic peoples.

There are many indications that the Sarmatians, considered to be a fraction of the Scythians (Sakas/Skolotians), and often mistaken for them, had R1a1 hp, and the Scythians proper—R1b. The Saxons (Saxons) and Goths may come from the Saks, and from the Sarmatians—the Vandals (Wand + Al, i.e. the Wends and Alans, or Wan + Dal, i.e. the Vans = Wends and Dalemintians = Dolintians/Dolinians).

A bronze sword and a graveyard of nomads, possibly Scythians, were recently discovered in Górzyca in the Lubuskie voivodship, some 200 km south-east of Mecklenburg. The graves there are about 400 years older than Tollense, which may prove that as early as 1700 - 1500 BCE peoples from eastern Eurasia reached these areas. However, these were not any great migrations or invasions, as there are no archaeological confirmations for this.

The bronze products discovered in these lands, such as those in Brody (also in Lubuskie), are mainly of local origin. The very name of Brody testifies to the existence of a river crossing (ford), whose unregulated riverbed and changing current as well as numerous backwaters and riverside swamps made it difficult for the tribes of Lusatian culture (Lusatians, Polish: Łużycy) to move. That is why such places were of great strategic importance. A similar logistic role was played by the later settlement in the nearby Lubusz, which defended the ford on the Odra River, as well as the aforementioned bridge over the Dolenica (Tollense). The problem is that archaeologists have not found any larger settlements from that period in the vicinity of Wiltzen (Polish, Wilczyn—Wolf town) so far. Perhaps they are still waiting to be discovered, or the defense of this trail was not needed then, and only periodically people traveled there from irregularly scattered villages in the area to repair the dykes.

In any case, the presence of a genotype similar to modern Poles in the 13th century BCE in Zaodrze (Behind the Odra River), is a real nut to crack for academics, who often try to make Germans out of these Proto-Slavs, i.e., descendants of Germans, not Poles.

Maciej Bogdanowicz, a historian running the RudaWeb website, reports that, according to estimates from genetic blogs, in both main component analyzes (PCA) the fallen by the Dolenica grouped similarly, as stated in the first communication in 2016: 8 each with Slavs and Germans, 1 with the Balts and 2 with Southern Europe ( Bogdanowicz, 2017 ).

He wonders:

“It is not known what the term ‘Germans’ means in this case from the point of view of population genetics. Over a thousand years B.C. there was no question of any Germanic people in today’s sense. According to Frederik Kortlandt, the beginning of Germanic ethnogenesis was around the turn of the eras, i.e. the millennium after Tollense (around 1250 BCE). According to the findings of the same linguist, in the 2nd thousand BCE in Europe we have only two Indo-European branches: Italo-Celtic and Balto-Slavic. The starting point for both was the Venetian ethnos, which archaeologically and genetically can be associated with the Central European Corded Ware culture (the predominance of R1a, but also a significant share of I2a, and also locally R1b). Today, the first of these language groups strongly correlates with the male haplogroup R1b, while the second one with R1a and I2a. Of course in the genetic pools of both ethnos, minor male components also participate, while the Balto-Slavic component is more diverse. In female genotypes, the components of both communities are more similar to each other, with the main role of the H mutation, but also the U mutation—the deeper it is, the more of it. In contrast, the modern German-speaking populations in the male haplogroups (Y-DNA) are a mix, in different proportions R1b and R1a, but with a significant share of I1—originating from Old European Scandinavians, most probably still non-Indo-European.”

Bogdanowicz (2020a) suggests that:

“These were also border regions between the Nordic bronze culture and the Lusatian culture. From the findings so far, it can be concluded that a group of warriors from the south-west was stopped at this point by the defenders of the crossing. These border guards from the side of the Lusatian culture territories turned out to be (in the light of the research conducted so far) the winners. Since they practiced cremation, they took their fallen and subjected them to a ritual typical of them. As is usually the case in such cases, the corpses of the defeated remained on the battlefield.

He realizes that the genes of the losers in this battle also do not give a definite answer about their ethnos: Celtic R1b on the one hand, Slavic I2a on the other. It can be said without much fear that they were an Indo-European group. However, what kind of cultural community they represented—it is difficult to judge for today, unlike the undoubtedly Slavic Lusatian culture. It is possible that they were a federation of some tribes close to the Lusatian borders, which decided to seize the Odra estuary, which is crucial for the Lusatians.”

The same year but in another article, Bogdanowicz wrote (2020b) :

“On the basis of the data currently available, it can be concluded that one of the parties to the conflict on the Tollense came from the circle of Knoviz and Unstrut cultures. From around 1300 BCE it covered the territories of today’s Central and West Bohemia, as well as Thuringia and partly Bavaria and Saxony. The other side represented the Lusatian culture, stretching from eastern Germany through almost all of Poland, reaching Moravia in the south and reaching as far as Volyn. The Knovizians were invaders, while the tribes of the Lusatian culture defended themselves. The invaders were literally shot from the arches. Most were killed with shots to the head and the chest. At the beginning of the battle, dozens of attacking warriors, hit by arrows, fell into the water while trying to force the crossing. Others were shot dead on the river bank, most often while escaping. The victors took their dead and killed their enemies, taking their more valuable equipment.

The whole battle was to last one day. It was initiated by the invaders’ attack from the west on a several-hundred-meter-long bridge. The impact was stopped and the attackers decided to cross the river in another place. The next stage of the fight, more downstream, was already dominated by archers, as evidenced by the numerous arrowheads found just below the crossing. Attempts to cross the river elsewhere have failed due to fierce defense or harsh natural conditions (deep current or marshy shore). Some warriors were killed in the river and others were thrown into it after their death. The last phase of the battle took place on the inlet cone (archaeological site Weltzin 20). The harder ground meant that the fight there was conducted in close combat with the use of wooden clubs and clubs, as well as brown swords and daggers. However, the archers continued to shoot at the combatants. Their victims were mainly those fleeing the battlefield, as evidenced by many wounds from arrows inflicted from the rear. It is possible that at this point the battle ended in a final defeat and the slaughter of the invaders. There could be 10,000 people fighting on both sides, but most often the number is estimated to be half as much and it is assumed that up to 50% will be killed warriors—primarily on the side of the attackers.”

It can therefore be assumed that the army from the region of the copper-bearing Ore Mountains tried to capture the port leading to the mouth of the Odra River in order to seize control of this branch of the Amber Route.

The historian from the RudaWeb website refers to the latest findings of geneticists, which showed the domination among the fallen, people from today’s Czech Republic and Germany north of Bavaria, i.e. from the areas where in the 13th century BCE there was a Knovizian circle. The coexistence of I2a and R1b among the fallen male haplogroups should not come as a surprise, as they are recorded in this area in 3 thousand BCE, and the connection of R1b with I2 around the middle Danube was confirmed already in the Lepenski Vir culture (Vlasac site) at the end of the 8th thousand BCE Thus, in the case of the overwhelming majority of those who died at the Dolenica, we do not have two separate ethnoses, associated with one specific male haplogroup, but one with two dominant. Taking into account the claims of peleolinguists (Alinei, Kortlandt and others) In Central Europe, the second half of the second BCE we have a well-developed Proto-Slavic region, with distinct proto-Celtic elements in the region of the Alpes. The origin of the Danube warriors from Scandinavia was ruled out by isotope studies. Also, Y-DNA analyzes do not support this direction (no derivatives of the I1 haplogroup), which together puts into question the participation of representatives of the Norse Bronze Age culture (alleged Proto-Germans) in the battle, although after it a typical Lusatian flesh-burn becomes popular in this circle. This suggests the expansion of the ideology of the winners from the Dolenica valley to the cultural environment closest to them.

The blogger notes that:

“The most interesting is the connection of the date and place of the battle with the archaeologically palpable beginning of solidification of the Lusatian culture in Western Pomerania. The description of the fight shows that already in this initial period, the tribes of Lusatian culture state had mobile and well-trained archers, who operated on the basis of a system of border fortifications in a coordinated manner and with a good understanding of the enemy’s forces. The further development and cultural continuity of the lands from the middle Elbe to the upper Dniester and from the Baltic to the middle Danube (Moravia), which initiated the separation of the Lechite language group, allows us to see the beginnings of the Polish nation at this time and place (the formation of the Lusatian culture).

The small participation of the warriors from R1a Bogdanowicz explains, as mentioned above, their victory in this battle and the collection of the bodies of the fallen and their burning, in accordance with the tradition of the Lusatians—Proto-Slavs. He mentions that: One sample of R1a (WEZ56: R1a-Z283 (xM458, V92) was found among those killed by the Dołęża River. This is a ‘paternal’ haplogroup, mainly for Balto-Slavic mutations. This indicates a representative of the Lusatian culture. His comrades did not find him on the battlefield. Hence, his body was not taken and cremated” ( Bogdanowicz, 2020b ).

5. Thesis about the Expansion of the Venetians to the Baltic Sea

The thesis that it could have been the expansion of the Venetians (Venedians = Veneds = Wends) to the Baltic Sea after the lost Battle of Troy, dating more or less to the same period (1184 BCE), seems to be quite controversial. Differences of up to 100 years in C14 dating are an acceptable error limit, especially in the case of contaminated samples.

The historically confirmed people of Enetoi took part in the Trojan War against the Achaeans. After losing the battle, they left their lands in Paphlagonia and went by ships to the northern Adriatic coast. It is possible that among the refugees there were also representatives of the Rasenian people, called by the later Romans Etruscans. Their arrival on the Apennine Peninsula is also estimated at the end of the 2nd millennium BCE.

Marcin Bielski, Polish historian from the 16h century, considered the Henetians to be the Sarmatian people (“Polish Chronicle” Vol. 1, Book 1) ( Bielski, 1597 ):

“This is also confirmed by Diodorus Siculus, writing: that the Paflagonian peoples took over the wide fields in the north and called themselves Sarmatians. This is why D. Tilemanus Stella understood when he wrote about the beginning of the nations, when he said this: And the Henets went out from the Black Sea, and, continuing, they filled a large part of the northern lands in Europe, and they still hold those lands as Ruthenia. The same, in a different place, all those people call Henets what they say in our Polish language today.”

Philip Melanchthon (1558) writes on the other hand:

“The House of Henet—of course it—neighbors Phrygia, then this country got the name of Paphlagonia from Paflagon, son of Phineus, and this people became famous by Homer and Herodotus. Then Ptolemy said that the Henets were the greatest Sarmatian people, which, after the destruction of Troy, dispersed widely, today occupies Poland, Ruthenia and large regions from the Vistula to the Oder and to the Elbe.”

The Enets on the Adriatic were called Venets, from Latin: venetus—blue, probably from the color of their eyes. Their cultural ties with the Etruscans are confirmed by scientists. The face ashtrays from the Baltic Sea are similar to the Etruscan ones. The similarity of the names Prusai and Etruscans is also not accidental (root *rus). Who knows if the Venetians, as the Wends, did not contribute to the formation of the Slavic ethnos after mixing with the then conquered local population. Some of the Etruscans accompanying them could in turn have given rise to Baltic Prussia, and perhaps later Rus.

Lithuanians, who may have arisen on a Venetian-Prussian basis, have long insisted that their ancestors founded Rome, and any endings of their words and surnames with -as, -is, -os are ancient remains.

Polish historian, Tadeusz Miller (2000) , in his work wrote that the Veneti/Venedi (Wends) created a powerful empire stretched from the Bay of Biscay to Berezina River (present Belarus).

Genetic research on the Adriatic Venetians is currently underway and can contribute a great deal to this matter ( Bogdanowicz, 2016a ). The Italian scientist Dr. Piero Favero is running a project called “Your Venetic Origins”, which aims to establish the genetic background of the inhabitants of the Veneto region ( Bozzolan, 2021 ). Already, however, many Italian scientists support the hypothesis that the relations of the Adriatic Venetians with the Baltic Vends should be taken seriously, and the expansion of this people extended even to Gaul (Armorica) and the British Isles, where they controlled, inter alia, tin mining (Wales).

Importantly, Favero also connects the ancient Veneti with the Lusatian culture (Map 4). He claims that “the Lusatian culture is the most specific form of the original Venetian population, and the problem is to find the correlation of subgroups related to R1a-Z92 and other R1a subgroups in the Lusatian culture between 1300 and 500 BC” ( Favero, 2012, 2017, 2018 ).

There are no doubts in this matter, among others such linguists as Françoise Bader (Sorbonne University) and Jadranka Gvozdanović (University of Heidelberg), who demonstrate the cultural unity of ancient peoples called Venetians, settled in the Baltic Sea region as well as on the Atlantic and Adriatic coasts. Genetic studies of haplotypes in these populations also confirm their common origin ( Bogdanowicz, 2016a ).

It seems that the Battle of the Tollense was not only about capturing the causeway on this river, which ensured a safe passage, but about taking control of the then world-famous deposits of amber, tin and copper. The Amber Route, which allows the trade of a “divine stone”, worth a few slaves in Rome, also found a little earlier before the Battle of the Dolenica, in the tomb of Tutankhamun (1333-1324 BCE), is just one of the goals of the Veneti expansion to the north. Tin (Polish: cyna) deposits (the Polish word “cena”—“price” comes from it) in the Ore Mountains (Polish: Rudawy) and the nearby copper mines are also very valuable (Polish: cenne, from “cyna”—tin) exploitation areas (copper + tin = bronze).

After the victory of the Battle of Dolenica, the Venetians (Wends) took over the entire southern coast of the Baltic Sea, establishing numerous trading posts there. The main port was probably Wolin, where Trygław = Trojan was worshiped). It is worth noting that Homer also calls Troy—Wilion/Ilion ( Agnosiewicz, 2016 ). The root *il—bright, is also found in the name of Illyria, which is considered by some to be the ancestral lands of the Proto-Slavs (similarly to Pannonia, Vindelicia, Raetia, Noricum, and Carantania). These are another strange nomenclature between the Trojan myth, the history of Rome and the history of the Slavic region, and the facts about the Battle of the Dolenica.

However, there are many more. The “Trojan Lands” were called pagan lands throughout Central Europe: from the Ruthenian lands (according to “A Word

![]()

Map 4. Distribution of the subclad R1a-Z92 cluster B (East Slavic I) with indications of the area of the Lusatian culture considered to be the cradle of the Venetians (venetostoria.com).

about Igor’s expedition”), through the Balkans, to Pomerania. The pagan times were called the “Trojan ages”. The Ruthenian chronicle also mentions the “Trojan way”. In the Bosnian tradition, Trojan was called “the tsar of all people and cattle”, which makes him similar to the image of Veles (Volos) by which he is known in the Eastern Slavs. In Serbian and Bosnian folk tales he appears as a “rich tsar” who lives on a prince’s mountain in a “Trojan castle”. It is no accident that the highest peak of Slovenia is called Triglav in honor of the mighty Trojan, god of the three worlds: Pravia, Navia, Javia ( Kosiński, 2019 ).

In the Westpomeranian Region (Polish: Zachodniopomorskie), there is the village of Trzygłów, which was called Trojanowo until 1946, which is actually one of many examples of identifying Triglav with Trojan. The main center of the Trojan’s cult and power was not only the above-mentioned Wolin, but the whole of Western Pomerania, including Szczecin and Branibór (Brenna) on the Havel (present-day Brandenburg), i.e. lands not so distant from Dolenica river.

Interesting remarks on possible connections between the Balto-Slavic peoples from the Baltic Sea and Troy can be found not only in the literature on the subject, but also in discussions in social media. Of course, this type of information cannot be treated as scientific sources, but sometimes you can come across views that can be the subject of important consideration. I do not underestimate any of the available knowledge channels, according to the principle: “Listen to everyone, search, think, analyze, do your thing”.

The anonymous author (nick: łużyce) of a quaint article on one of the internet blogs (“Salon24”) writes that:

“The strength of the Trojans and their main center—Wilion, that is Wolin, was based on extensive trade contacts, control of key raw materials and trade routes between the north and south. This Trojan alliance could eventually lead to the takeover of the entire Baltic trade, i.e. the takeover of Helen. The ten-year war against Troy for “Helena” would be a war to control the trade of the Baltic and the Amber Road, the most important route in the history of Europe, which is known not to be stable at all, but ran through various routes: from the Jutland Peninsula and the Elbe, through Wolin and Odra, Vistula, as far as the Gulf of Riga, the Dvina and the Black Sea. The Odra River route had its main advantages, as it connected with Silesia that is the Mecca for raw materials and mining” ( Bitwa nad Dołężą, 2016 ).

An interesting concept is also the theory of Felice Vinci, who believes that Homer described the events not on the Mediterranean Sea, but on the Baltic Sea. According to him, the Trojan Battle took place in the vicinity of today’s Finnish Turku, and Hellas is a country whose remnants on the Baltic Sea are such names as Helsinki or Hel. He cites a number of topographic evidence that matches the Baltic areas, but has nothing to do with the layout of the terrain and distances from the Mediterranean basin described in the “Odyssey” ( Vinci, 2006 ).

It is also possible that the Venetian people worshiping the Trinity (Troy) of the gods—the Sun, Moon, Earth—founded their cities, originally called the Troys, in various places of conquered Europe. The presence of the Venetians in Gaul is confirmed historically, and according to legends, the name of the city Paris derives from the Trojan Paris. Rome was also to be founded by a refugee from Troy-Aeneas, with a very similar name to the people of Enetoi (Henetoi-Venetians-Wends). I have already mentioned this before, explaining the name of the king of Troy, Priam, as the nickname “priamyj” (Russian: прям[ый]—simple, kind). His real name was supposed to be ...Podarces (Polish: podarek, dar—gift), like the name of the Slavian god Darzbog, with similar root *dar (gift). The naming similarities (L)Ach[aean]s and Lachs are also worth attention ( Kosinski, 2017 ; Jagodziński, 2015 ). We also have strange similarities to the shield of Achilles, the hero from Troy, described in the “Iliad”, with the so-called Disc of Nebra, found in Saxony-Anhalt, and dated around 2000 BCE.

Polish author Stanisław Bulza wrote about the Slavic character of Trojans as well, unfortunately his articles on the “Polish Club Online” web portal are no longer available and survived only in fragments on Czesław Białczyński’s blog ( Bulza, 2017 ), which only confirms my belief that the Internet is not the best place to store it type of studies. I managed to copy them into the handy archive in advance and I can refer to it here. The author notes that in the Trojan War, the Henets fought on the side of the Trojans. In the “Register of Ships” (“Iliad”, book II, 843-847), Homer wrote about them: “The Paphlagonese at Pylajmenes with a hairy breast from the land of the Enets came, where the wild mules breed. These headquarters were at Kitoros and around Sesame. On the banks of the Parthenos, they lived in the famous houses of Kromna, Aegialos and the haughty Erityns”. The cities mentioned by Homer: Kitoros and Sesamos were in Paphlagonia.

However, according to Herodotus, the Venets (Henets) came from eastern Europe, and according to Titus Livius, they reached the Adriatic Sea in the 13th century BCE along with the Trojans led by Antenor and defeated the Euganeans, founding their state—Veneto, in the northeastern part of the Apennine Peninsula. The first archaeological traces of the Venetians, however, are recorded around 950 BCE, and the peak of their development falls in the period of the 6th-4th centuries BCE. Only later, according to some historians, they were to go to the north and west of Europe.

Bulza writes similarly: “(...) after the Trojan War, Aeneas and Antenor with the Trojan people and Henet left Troy and, encircling the Black Sea through Thrace and Macedonia, came to the territory of northern Italy, and later some of them reached the north as far as the Baltic Sea”. At the same time, while Aeneas is considered to be the legendary progenitor of the Romans, Antenor, who was an advisor to King Priam, is considered to be the ancestor of the Venetians, and he is the source of the old Polish word “antenat”—ancestor. According to Bulza, the Romans are not descendants of the Trojans, but the Venetians1. Also thesis about the Trojan character of the Franks is false, according to him.

It would fit my thesis about the participation of the Slavic Venetians (Venetians), as descendants of the Trojans, in the Battle of Dolenica, assuming that their migration to the Baltic lands took place much earlier than historians assume around the mouth of the Oder ( Białczyński, 2019 ). However, in the myth about Troy, the Achaeans are winning, and not the Venetians, as by default over Dolenica, who may already be local people at that time. It is also possible that he took these stories from merchants traveling along the Amber Trail from the north to the south, and the knowledge of the kinship between the Adriatic Venets and the Baltic Venets he knew allowed him to treat them as the myth of the Old Hellenic (pre-Greek).

We know that the war for Troy lasted 10 years. It is also possible to defeat the Wends in one battle, but to win the entire long war. Perhaps, after losing the skirmish, the Weneds used some progress, like the Trojan Horse, to change the balance of power and possibly win Wolin—Troy. We know from historical evidence that a black horse was kept in the Trygław (Trojan) temple in Szczecin, which was also a cult animal for the Trojans. Thus, we have a number of topographic, climatic, nomenclature, cult, and time similarities between Homer’s Troy and Wolin and the nearby Battle of Dolenica (Tollense).

It is possible that the Weneds had already gained control of the deposits in the Czech Ore Mountains before the battle, and therefore they may be the people from southern Europe. After taking over such valuable areas, rich in natural resources, their next goal could be to seize power over the Amber Route, which required pressure to the North.

Bulza recognizes as Snorri Sturluson that the Scandinavians also come from Troy, called Asgard in “Edda”. As we know, the Nordic sagas, admittedly, speak of a war between the Aesir and Vanir (Vans = Wens = Wends) at first, but then an alliance is established between them. This may, in turn, refer to information from geneticists that the ancestors of modern Poles (Lachs, Wends) and Scandinavians (Danes), possibly against Italo-Celts, participated in the Battle of Dolenica. If, however, the “Slavic” hg I2a was considered the one that was connected in the first communication with the people of southern Europe, and R1a with the ancestors of Poles and R1b/I1a with the Scandinavians (or rather Scots, according to Ch. Sell (2017) ), then we have a good genetic mix -you have, which can be interpreted differently. Therefore, we need a lot more detail to reliably analyze this topic in terms of the presence of male (Y-DNA) and female (mDNA) haplogroups, dominant in individual ethnic groups, forming clusters also due to linguistic similarities.

It is worth knowing that Iranian chroniclers (Ibn Khurdazbich, Kitab al-mamalik, p. 154; Ibn al-Fakich, Kitab al-Buldan, p. 271) recognized the “Ruthenian” so-called Norman merchants as “one of the Slavic tribes”, which Bulza corrects when explaining that the Slavs and Normans had common ancestors, namely the Paflagonese (later Venetians) and the Trojans. However, this fits in with the thesis of M. W. Lomonosov that the Varangians (Waregi) came from Prussia, not Scandinavia ( Lomonosov, 1952 ). Perhaps they were the Polabian Wagrians (Wagri), who, together with the Rugians, ruled on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea.

A detailed report with a detailed analysis of the genotypes found in the remains found at the Dolenica River, as long as it is not manipulated by the Germans, should answer many questions. So far, scientists say little about the haplogroups of this battle as if it were a taboo subject. Unfortunately, after the first spontaneous announcements in Science from 2016, we can already see a change in the narrative in this matter, and on the Eurogenes website, commentators mention cases of omitting and questioning in official publications the facts of the detection of hp R1a DNA in samples from Dolenica, commonly attributed to the Slavs: Poles have R1a-M417 60%, and the Sorbs 65% ( Kowalski, 2020 ). It looks as if the Germans were ashamed of their possible Slavic roots or wanted to remain silent about the participation of the Slavs in this battle.

6. Summary

One of the possible causes of the battle could have been a trade expedition to the North of proto-Celtic merchants, with the participation of Old Europeans from southern Europe, to trade with the proto-Slavic Łużyki/Łużycy (Lusatians). Unsure of their reaction, however, the traders hired mercenaries from different parts of the Celtic sphere for transport protection. They were professional soldiers with bronze weapons, and some of them mounted horses.

A caravan with military assistance went north to sell metal products, and probably return with amber and furs. However, while crossing the Tollense River, she was attacked by the locals, who instead of paying for goods decided to get them by force. The defeated as well as the winners left their skeletons, weapons and ornaments at the river Dolenica, which could not be extracted from the bottom of the river or swamp. This version of events assumes the exclusion of the Scandinavians by isotope research, so the war looks like a conflict between proto-Celtic and proto-Slavic people.

It should be remembered that autosomal DNA research shows great genetic similarities between the remains from the battlefield of the Dolenica river and the Slavs, which leads to the conclusion that it could have been a large skirmish of local Wendish tribes with the participation of foreign mercenaries, perhaps for dominance over the entire Proto-Slavic area of that time.

I also leave the thesis about the Venetian expansion to the north for consideration. However, if we assume that the Sarmatian Venetians are the descendants of the Paphlagonese and Trojans, and the (L)Achaeans are the Lachai (Lachs), i.e. a people related to them, the question remains why so much conflict arose between them. Homer brought him to the myth of the kidnapping of the beautiful Hellena. Who knows if the reason was more prosaic and it was not about love and betrayal, but about taking influence over Hellas, that is, the “land of the sun” on the Baltic Sea, with rich deposits of amber, a priceless “sun stone”.

After all, I am more and more convinced by the option of playing the war for Troy in the old Slavic areas at the mouth of the Oder, and not somewhere in ancient Greece. In my opinion, both the mythical account of Homer and the location of Troy by Heinrich Schliemann, a German amateur archaeologist, who was immediately hailed as the discoverer of this mythical city, are doubtful, although he did not manage to find too many artifacts or remains there, as is the case with in the Tollense Valley. The term “Pomeranian Troy” as used by Vandkilde may therefore not be so far-fetched. Moreover, as you can see, there are many reasons to suppose that Troy was in fact located on the Baltic Sea, as Felice Vinci claims.

There are still tons of unanswered questions. However, it should be believed that sooner or later the truth hidden by the Dolenica valley near Wilczyn will come to light.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Detlef Jantzen for meeting in his team’s workshop in Schwerin in 2016 and providing me with basic information about the ongoing excavations at the Tollensetal archaeological site and the preliminary results of the research.

NOTES

1Venetians > Venets > Weneds > Wends > Slavs. You can also add the Vandals, which many old authors linked with the Wends (Slavs), for example in the commentary to Virgil’s Aeneid, Maurus Servius Honoratus, indicates the relationship between the Veneti people and the Vindelici.