Interests and Influence: Stakeholder Participation in the Regulatory Process ()

1. Introduction

Stakeholders’ participation in public decision-making processes has been increasingly demanded and valued. In recent decades, society’s engagement and the number of practical experiences of citizen participation in governments have increased. Consultation with interest groups for policy formulation and regulatory decision-making is a feature already common to several countries, which use a wide variety of techniques to engage the public in different areas of government, as shown below. In the regulatory process, the search for interventions that achieve the desired results has motivated the restructuring of policies and instruments. At the international level, many countries already have regulatory quality programs to rely on smarter interventions, improving systems that manage the design and implementation of regulations. Regulatory quality would be achieved as processes are more transparent and use tools that improve the design and implementation of regulations, and the possibility of active participation of stakeholders in the regulatory process. Thus, social participation has been considered essential to ensure that interventions are effective and efficient (Emery et al., 2015; Michels, 2011; Nabatchi, 2012).

In this research, the relationship between society’s participation and the formulation of regulatory decisions could be better understood using two fundamental concepts: interests and influence. Different groups in society represent different interests. Stakeholder participation is generally voluntary and depends on their own interest in interfering in regulatory formulation and decision-making. Thus, each group acts strategically in order to influence decision makers in the way that their interests are achieved. In the regulatory process, stakeholders have interests that they wish to see reflected in the regulator’s decisions, but there is variation in the degree of influence of different groups. Understanding how the regulatory game works, in terms of the relationship between the interests of groups and the influence exerted by each one of them, is the objective of this article. This research is characterized as a case study and used an independent regulatory agency to investigate this issue. Based on the characterization of its mechanisms for consulting society, regulators and representatives of relevant stakeholder groups were heard about the relationship between the interests of each segment and the influence exerted on the agency’s regulation.

The article is structured in six parts, including this Introduction. Section 2 discusses the importance of the concept of participation and the different approaches and types of instruments used by the State to engage society in its decision-making process. It also addresses the implications of different theories of interests and influence for the regulatory process, and the role of participation for regulatory quality. In section 3, regarding the results, the different strategies that enable society’s engagement in the regulatory process of the case studied are presented, as well as data on the participation of stakeholders in these mechanisms. A specific typology is adopted in the classification and analysis of mechanisms for understanding different degrees and types of participation. Then, the responses of regulators, industry and consumer representatives interviewed are analyzed. The questions are related to the relationship between degrees of interest and influence capabilities of stakeholders, and different standards of action and pressure strategies of these segments, channeled in the regulatory process of the agency. After the presentation and analysis of the data, section 4 discusses the main points relevant to understanding the relationship between interests and influence of stakeholders. This section seeks to reconcile different theoretical perspectives on the competition of stakeholder groups and the importance of actors and institutional structures in the influencing process. In the part dedicated to Conclusions, a summary of the results obtained and the main notes of this research on the topic of interest and influence of stakeholders in regulation are presented.

2. Participation and Regulatory Quality

2.1. Participation

The concept of public participation can be considered polysemic (Dean, 2017), malleable (Cornwall, 2008), complex and controversial (Rowe & Frewer, 2004, 2005). Public participation is an umbrella set of practices of involvement or consultation with citizens to incorporate their concerns, needs, interests and values in public affairs (Nabatchi et al., 2015). Participation can also be referred to as interest in political dynamics. Political participation refers to attempts to influence others—any powerful actors, groups or business companies in society—and their decisions that concern social issues (Talò & Mannarini, 2014). But even though scholars have suggested increasingly broad definitions of political participation, the “focus has remained on a more confined set of citizen activities” (Ekman & Amna, 2012). In this process, members of society—those who do not belong to state structures—share power with public officials to take substantive decisions and actions related to the community (Roberts, 2004). This participation can occur at different stages of the policy production process in organizations or institutions, such as the agenda setting, decision-making, policy formulation and implementation stages (Rowe & Frewer, 2004, 2005). The quest to increase the legitimacy of policy-making processes can rely on new forms of direct citizen participation, because such participation aligns with the general perspectives of the public, or because such participation can fill democratic failures in policy-making conventional representative process (Fung, 2015).

In public participation processes, the perception of motivation is fundamental. It is based on the position or interests of individuals. Opportunities for participation are considered less productive when they are based on the positions of individuals (what a person or group wants, or the defense of a demand) than when they are based on the actual interests of individuals (what is the reason for a person or group to want it something, or what are their needs, values and concerns related to a demand) (Nabatchi et al., 2015). It is important to measure the motivations of both potential participants to engage in decision-making processes, as well as public agents to create and expand this possibility. However, it must be considered that there is a difference in the perspectives of public agents and citizens in their conceptions of participation and engagement. For public agents, this is an activity that above all allows them to bring information to interested parties about the government’s proposals, or to enable them to choose between pre-defined alternatives. Stakeholders, on the other hand, generally understand that they must have a final word on the outcome at stake (Shipley & Utz, 2012).

Generally, stakeholder participation is voluntary and depends on their interest in collaborating with these processes. Thus, incentives to participate are essential. The basic “calculation” made by the stakeholders takes into account an estimate of how much of their expectations can be achieved with their participation, also considering the time and energy to be used by them. When stakeholders perceive that they can achieve their goals on their own or through alternative means to participation, or regard their participation as merely consultative or formal, incentives are low. And there are high incentives if there is a direct relationship between participation and significant results for the definition of concrete, tangible and effective policies (Ansell & Gash, 2007). However, participation can contribute to increasing citizens’ trust in government when participants’ objectives are met or public officials show commitment to identifying and understanding the interest of stakeholders during a deliberative discussion. For example, exposing stakeholders to comfortable meetings and productive discussion tends to make participants more tolerant of others with whom they disagree (Halvorsen, 2003).

2.2. Participation, Interests and Influence

It is generally accepted that the relationship between social interests and political outcomes varies according to institutional context (Krasner, 1984; March & Olsen, 1983; Moe, 1987). Different theories explain these relationships with different emphases, but they all agree that, to some extent, both elements—social interests and political institutions—play a relevant role. The economic theory of regulation explains how economic interests translate into public policy through political influence on institutions that operate to allow these interests to be turned into results. From this perspective, some theories deepen the argument that pressure groups compete for political influence and that political balance depends on the efficiency of each group in producing pressure (Becker, 1983; Peltzman, 1976; Stigler, 1971). The positive theory of institutions, on the other hand, focuses on the implications of the rules resulting from voting and, in particular, the instabilities and paradoxes of the majority of those who govern (Arrow, 1963). Each group will try to put in place rules that allow them to get results for their own benefit and will always seek to adopt rules that are more favorable to their own interests.

There is a certain consensus that regulators should be concerned with serving the public interest, understood as “conflict and accommodation of interests” (Cochran, 1974). Both individuals and groups of individuals enter the political arena to further their own interests (Benditt, 1975). In this political process, they can receive attention and, in some cases, satisfaction. These groups compete with each other, and their capacity for pressure and access is what, to a large extent, determines decisions. Therefore, government decisions are the result of conflicts that occur between the different interests promoted by the stakeholders. For public interest theories, the role of the regulator is mainly focused on solving market failures (Laffont & Tirole, 1991). And capture theories or interest group theories emphasize the role of interest groups in shaping public policy and regulatory interventions (Levine & Forrence, 1990). Both elements are valid in the decision-making process and it is clear that no regulator dares to do so without understanding the different interests of the interested parties.

The role that stakeholders play in exerting pressure and influence has also been studied in theories that seek to explain who and what decision makers pay attention to. In the broadest sense, stakeholders can be defined as “an individual or a group that can affect or is affected by the achievement of an organization’s goals” (Freeman, 1984). Thus, for regulators, any person or group could be considered a stakeholder that should be included in the decision-making process. Stakeholder participation can contribute to the success of a government intervention as well as to its failure. Regulators’ knowledge of these stakeholders is vital for the institution responsible for the intervention, in order to understand their potential attitudes and actions, as well as the development of strategies that they can put into practice. Understanding these differences, needs, priorities and perspectives is essential for the regulator in its effort to try to avoid mistakes and poor implementation of decisions that could translate into poor performance, failure or disaster (Bryson et al., 2011).

However, to what extent is this influence able to modify the results of the decision-making process and how does it interfere in the assessment of regulatory proposals? Measuring the degree of stakeholder influence has been a difficult issue to achieve because there are often no clear instructions on how institutions should handle stakeholder input. Some trends focus analysis on the normative reasons why it is legitimate and relevant to meet certain demands and groups (Freeman, 1994). However, power relations between stakeholders and regulators also deserve attention, as well as the degree of urgency that intervention may require (Mitchell et al., 1997). Thus, regulators need to properly understand the categorization of stakeholders in order to respond to their interests and ability to influence. Its correct identification and analysis are the first step in this process. There is also a need for formal channels of participation and for the regulator to maintain procedures that allow the involvement with these groups during the regulatory process.

2.3. Participation in Regulation: Stakeholders at Anvisa

In recent decades, the promotion of regulatory quality has been sought through reforms aimed at applying a set of processes, principles and tools that, combined, add value to the desired regulatory outcome. An important component of regulatory quality would be the use of tools that enable stakeholder participation in decision-making. The active involvement of those who may be affected by regulatory decisions and may provide evidence on issues to be resolved and possible solutions to address them, would improve the quality of rulemaking (OECD, 2017, 2019). However, there are still doubts among researchers whether this reform trend was also accompanied by an increase in the quality and effectiveness of policies (Rowe & Frewer, 2004). Also, this real wave of possible transfer of best practice models to developing or transition economies has been seen with additional difficulties related to a gap between these practices and administrative, legal, political and economic processes (Dubash & Morgan, 2012; Zhang & Thomas, 2009).

The Brazilian regulatory system follows this trend of dissemination of regulatory reforms in developing countries (Peci et al., 2020). An important process was carried out from the 1990s to the early 2000s to create a dozen independent national agencies (Cunha & Rodrigo, 2012). Today, the country has 11 agencies in the federal government and, due to a clear process of institutional isomorphism, there are also dozens of agencies of this nature at the local level (states and municipalities) (Bianculli, 2013). The institutional arrangements of federal agencies have a common basic model, but they carry differences in various aspects of structure and procedures. Here, we will analyze the participation of interested actors in the regulatory process of the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (Anvisa), considered the largest among Brazilian regulatory agencies (Ramalho, 2009b).

Created 20 years ago, Anvisa has today a relative degree of institutionalization for the development of its normative production capacity and its international leadership. Its role involves the regulation of relevant markets, such as medicines, medical devices, cosmetics, sanitizing products, food, pesticides, tobacco, among others, in addition to controlling the flow of products and people in ports, airports and borders, and the federative coordination of the Brazilian National Health Regulatory System (SNVS) (Ramalho, 2009a). This broad spectrum of regulation of different markets by Anvisa means that there is a wide range of actors interested in its decisions.

Regarding its decision-making process, since 2008, Anvisa has had a program of good regulatory practices (Ramalho, 2008; Anvisa, 2018), which include the promotion of transparency and social participation. Anvisa’s regulatory quality policy provides that the agency must guarantee mechanisms for the participation of interested parties and agents affected throughout the process in order to receive relevant subsidies for the quality of the analysis that will guide its decision. Anvisa can use different mechanisms and cover different target audiences to carry out consultations, according to the nature of the information it intends to obtain.

Despite the great impact of Anvisa’s regulation on the economy and society, its regulatory decision process has been little studied, in particular the participation of interest groups in the agency’s consultation mechanisms (Ramalho, 2009a; Saab et al., 2018). Thus, this research will emphasize empirical data and, therefore, will use the case of Anvisa to study the consultation mechanisms of an independent agency to deepen the understanding of the relationship between group interests and their influence on regulation.

3. Methodology

The research investigated the dynamics of interaction between stakeholders and regulators in Anvisa’s consultation mechanisms, in particular the relationship between the interests of each segment and their influence on the agency’s regulation. The methodology adopted in the research is characterized as quali-quantitative, in order to obtain the benefits of complementary approaches to data collection and analysis. Regarding quantitative data, it was investigated the interaction and the number of participants, by stakeholder segment, in each type of participation mechanism, over time. In the case of qualitative data, documentary analyzes were carried out on legislation, documents and information. Interviews were also carried out with key actors. Qualitative data served to deepen the analysis of the strategies used by stakeholders in the interaction process with Anvisa.

Data collection from official sources was carried out directly on the Anvisa Portal and other websites, or through formal requests for information to the agency through the Citizen Information Service (e-SIC) between January and December 2019. In the interviews, a semi-structured script was used with pre-defined questions for open answers that aimed to ascertain the perception of key actors about this process of interaction and participation.

Nine interviews were conducted to determine the perception of key actors about this process of interaction and participation. The selected key actors belong to three distinct groups: regulators, regulated and consumers. In the case of regulators, former directors and current managers of Anvisa were included. For the regulated group, the selection involved members of the governing body of national entities representing the pharmaceutical industry—a relevant economic sector among the markets regulated by the agency. In relation to consumers, the interviewees belong to the direction of national civil entities for the protection of consumers/patients. Data analysis of the interviews was carried out in order to verify agreements and disagreements between the respondents’ answers, by segments (regulators, regulated and consumers). After finding the conformity of responses by segment (and dissonant responses), the segments were compared to determine patterns of opinions and behavior imputed (or self-imputed) to stakeholder groups related to Anvisa’s participation mechanisms.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Social Participation Mechanisms

Over its 20 years, Anvisa has been adopting several strategies that enable the participation of interested parties in the regulatory process. There are two main forms of interaction between Anvisa and society: official communication channels and institutionalized participation mechanisms. Anvisa’s communication channels receive requests for information and assistance (Ombudsman, Call Center and the Parlatório Meeting System) and disclose information unilaterally (Portal and social networks). Institutionalized participation mechanisms, on the other hand, aim to represent segments of society in collegiate structures and receive contributions on Anvisa’s proposals in remote or face-to-face consultations.

Anvisa has innovated its participatory mechanisms through the creation of Partial Early Consultation in the RIA Process, Directed Consultations, the ICH Regional Consultations, and Sectoral Dialogues. The first one is an open mechanism that is intended to collect evidence on a preliminary regulatory impact analysis (RIA) report. Directed Consultations aim at collecting data and information with agents involved and affected by regulatory action and may occur at any stage of the regulatory process to expand the available evidence or validate information already raised initially. In the case of the ICH Regional Consultations, information is collected to guide proposals that are under discussion within the scope of the International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use, of which Anvisa is a member. Finally, Sectorial Dialogues are characterized as face-to-face or virtual meetings aimed at specific audiences in order to more quickly validate information on stages of the regulatory process. This mechanism differs from public hearings by being more informal and having flexible meetings, bringing together a more restricted audience.

The functioning of collegiate bodies varies greatly. The Advisory Board depends on the convening by the Ministry of Health and traditionally has little expressive agenda. The last record on the Anvisa Portal is the Minutes of the 45th meeting, held on September 16, 2015. Until 2018, the Scientific Committee on Health Regulation (CCVisa) had regular meetings, but with a poorly structured agenda of relevant current issues very variable. On the Anvisa Portal there is no information regarding the holding of meetings of the Technical Chambers. As for the Sectoral Chambers, the most recent record of the meeting is from 2014, for the Sectoral Chamber of Health Services. In 2018, Anvisa established seven working groups with the participation of external members to formulate proposals for consultations public services. Although not linked to the regulatory process, only the working groups seem to be effective structures among the collegiate bodies.

In the case of consultations with stakeholders, the mechanism most used by Anvisa is the so-called “Public Consultation”, used to disclose a proposal for comments, in the form of a draft regulation. In 2018, there were 1195 participants in public consultations, distributed in the segments of professionals (47.4%), regulated sectors (26.4%), government (7.9%), citizen (5.5%), among others. That year, the 11 contributions received by Anvisa from consumer protection entities represented 0.9% of the total.

In addition to public consultations, Anvisa developed other forms of stakeholder participation. The elaboration of the Regulatory Agenda for the period 2017-2020 had 964 participants from the segments of health professionals (30.3%), companies (28.9%), citizens (24.0%), government (4.6 %), researchers (4.4%), professional associations (3.4%) and consumer organizations (0.9%), among others. Between 2016 and 2018, the segments of the 492 participants in the public hearings were companies (49.2%), professional associations (15.0%), SNVS representatives (11.4%) and government (4.7%), between others. The only Partial Early Consultation in the RIA Process carried out by Anvisa in 2018, on front labeling for food packaging, had 3674 participants from the segments of citizens (60.7%), professionals (17.7%), companies (12.7%), researchers (4.0%), among others (5.0%). In the segments grouped under “others”, there was participation of the government (0.9%) and consumer entities (0.8%). Anvisa held seven Sectoral Dialogues in 2018, totaling 462 participants, distributed in regulated sector (58.7%), SNVS representatives (29.0%), professional associations (3.7%), government (2, 2%) and citizens (1.5%), among others.

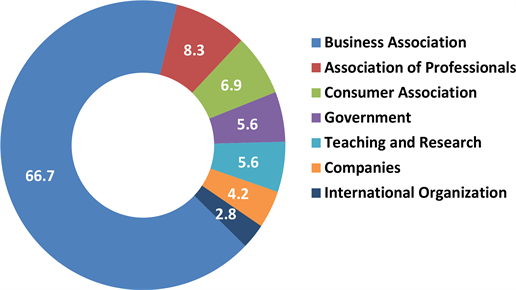

The participation of stakeholders in Public Meetings of the Board of Directors of Anvisa is represented in Graph 1. This participation occurred in deliberative matters of regulation of the 2018 meetings in the form of oral arguments. This participation must be requested prior to the meeting, being accepted or not by the Board, according to formal criteria of deadline and legitimacy of the applicant.

According to the data presented in this section, it is possible to verify that there is a wide range of mechanisms adopted by Anvisa in its regulatory decision-making process. In addition, there are different stakeholder groups that participate in these mechanisms. There are also variable frequencies of presence of each of the groups depending on the type of mechanism observed.

Mechanisms typology

In this research a typology of participation mechanisms has been developed, using criteria different from those of the classification adopted by Anvisa. The

Source: author’s elaboration.

Graph 1. Participants in public meetings of the board of directors of Anvisa, by segment, 2018 (N = 72).

official classification, called “social participation menu” (Anvisa, 2021), uses target audience criteria and stages of the regulatory process in which the mechanism is used. In its classification, Anvisa neglects the mechanisms of the Advisory Council, the Scientific Committee on Health Regulation (CCVisa), the Technical Chambers and the Sectorial Chambers. Although Anvisa includes in the classification the Focus Group and the Consultation for Review of Guides, these mechanisms were conceived recently and never used in practice in the agency. For this reason, they were not considered for this research.

The typology developed here (Figure 1) adopted two other classification criteria to value the practice of using mechanisms by the agency, as shown by the data collected in the research. The first criterion is the degree of participation of each mechanism. By restricted participation, it is understood that the mechanisms are addressed to certain groups of stakeholders, and not to any interested party. In the case of wide participation, there are channels or mechanisms that allow society to interact with Anvisa in person or at a distance, as long as there is no barrier to the selection of participants. The other criterion is the relation of mechanisms to the decision-making process. Thus, each mechanism was placed in one of two categories, whether or not it is linked to the design, elaboration, adjustment or final decision in regulatory proposals.

As can be seen in Figure 1, most participation instruments are not formally related to the regulatory process. These are mechanisms characterized as communication channels (wide participation) or representation boards (restricted participation). Among the mechanisms related to the regulatory process, those that can count on broad participation have generally been used by all stakeholder groups, in order to monitor and contribute to discussions on Anvisa’s regulation for the next period (Regulatory Agenda) and proposals of norms elaborated by the agency (Public Hearings, Public Consultations and Partial Early Consultation in the RIA Process). Finally, there is a set of mechanisms related to the

![]() Source: Author’s elaboration.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Figure 1. Classification of Anvisa’s social interaction mechanisms, according to linkage to the regulatory process and degree of participation.

regulatory process that only allow limited participation (Directed Consultation, ICH Regional Consultations, Sectorial Dialogue and Public Meeting of the Board of Directors). These are mechanisms that produce a discussion that is more focused on certain key aspects of regulated objects, with audiences that are more qualified, as they have more capabilities.

4.2. Alternative Mechanisms for Participation: Meetings and Events with Anvisa’s Directors

Data on the public schedule of Anvisa directors were also collected and analyzed. These data reveal a lot about the pattern of interaction of the external public with the agency. Of the 2129 appointments disclosed in 2018 by the five members of Anvisa’s Board of Directors, the meetings granted to the external public represented 29.8%.

The main themes of these meetings with external actors ranged from institutional presentation (32.3%), Anvisa’s regulation (26.6%), agency authorization requests (20.0%), meeting with no informed subject (16.7%), and administrative appeal to be judged by the Board (4.4%). What stands out most about the commitments of the directors, however, is the proportion among those interested who have meetings: 79.1% of the meetings were held with companies or their representative associations, compared to only 2.5% with civil organizations of defense of consumers or patients, among other actors (Table 1).

When it comes to external activities of directors, in meetings and events held in Brazil (but outside the agency’s headquarters), the proportion among the predominant agents changes, but the advantage for companies remains ahead of the others with 36.2% of cases, followed by government (32.5%) and international organization (15.3%), among others. It is noteworthy that, in the external meetings, the entities representing consumers and patients did not reach 1.0% of the total cases.

The regulated sector has promoted many events to discuss technical issues, inside and outside the agency’s headquarters, which greatly increases direct contacts

![]()

Table 1. External agents received at meetings by the Board of Anvisa, 2018.

Source: author’s elaboration. *Others: “SNVS”, “Judiciary” and “Not informed”.

between managers and directors of Anvisa and company representatives. As can be seen in the following section, the three groups of interviewees mentioned the meetings of external actors with the Board and technical structures of the Agency as a type of mechanism not officially intended for the purpose of social participation, but with great effectiveness. Thus, these specific interactions, through meetings and events, have been identified as one of the most used ways to influence Anvisa’s decisions, especially by stakeholders in the regulated sector.

4.3. Interests and Influence: What Regulators, Regulated and Consumers Think

This section presents the results of the analysis of interview data (according to synthesis at the end of the section, in Chart 1). Respondents were asked about the different degrees of stakeholder interest in Anvisa’s decisions. Great agreement was found between the views of the three groups of respondents. Regulators consider that the different stakeholders do not have the same degree of interest. They understand that some sectors that represent the interests of society are strong, but not well organized. On the other hand, the regulated sector is quite efficient, it has very organized business associations. The representatives of the regulated companies interviewed also understand that there are different degrees of interest among the different stakeholders, and that the interaction carried out by the industry is a much more permanent and in-depth process. Finally, consumers consider that the main difference is in the objective of each group. While the regulated sector aims to reduce economic losses, consumers want greater access and safety in their consumption. Thus, what would explain this variation in degrees of interest is the existence of a great difference in the purpose of one sector and the other, as will be seen in the Discussion section.

The interviews also identified differences in the relative effectiveness of participation mechanisms for the industry or consumers to achieve their goals. In the view of regulators, the most effective mechanisms for the industry would be those that generate specific interactions with closer and deeper discussion. These specific interaction mechanisms are those restricted to a few actors or carried out in person, and some mechanisms that are not officially related to the regulatory process (cases of Working Groups, Technical Meetings and Events). As for consumers, regulators understand that the most effective mechanism is Public Consultation, because it would be a form of cheap participation and no access restrictions for any interested party, despite the recognized problems of language and complexity of the issues.

When asked about the treatment given by Anvisa to the different stakeholders in the participation channels, all groups of interviewees understand that Anvisa’s treatment of stakeholders is not equal. Regulators recognized that they themselves do not provide equal treatment to different agents, despite indicating that there is an attempt to establish universalist criteria and standardize the routines of participation mechanisms. Industry representatives revealed that in addition to not considering that there is equality, they understand that equal treatment should not be sought. For consumer representatives, the greater or lesser attention of Anvisa depends on how much society mobilizes. Because when consumers do not participate in a qualified way, with greater investment in time, elaboration of studies, etc., what prevails is the vision of the regulated sector.

Respondents were also asked about the strategies used by stakeholders to influence Anvisa’s decisions. With regard to Anvisa’s official mechanisms for the participation of society, respondents consider Public Consultations and Public Hearings as the types most commonly used by Anvisa. Partial Early Consultation in the RIA Process emerged in interviews as a promising new mechanism. Regarding alternative strategies, all groups of interviewees recognized that, in addition to the formal channels of participation, there are different ways to influence Anvisa. Several means were mentioned for this, with options ranging from soft forms of influence or suggestion, to the exercise of strong pressure or even embarrassment in the decision-making or action of the agency.

Regulators recognize that their own perception of the urgency of deciding and evaluating the best alternative has been influenced by a diverse set of unofficial ways. They admitted that the most effective forms are those that are not clearly established as mechanisms for institutionalized participation in the regulatory process at Anvisa. Examples cited by regulators are the media (public opinion) and the pressure and demands exerted by the government (especially the Ministry of Health, the Agency’s supervisor) and members of the National Congress, which in many cases have an electoral campaign financed by companies regulated by Anvisa. The pressure exerted by members of the Legislative is not only carried out through the organization of meetings with Anvisa’s Board of Directors. Between 2009 and 2018, Anvisa received 117 petitions from the National Congress with requests for information about its performance on different topics, with emphasis on medicines (36.8%), pesticides (18.8%) and foods (8, 5%). In the same period, 23 Legislative Decree proposals were presented in the Chamber of Deputies and two in the Senate to stop normative resolutions and even Public Consultations published by Anvisa on topics such as medicines, food, pesticides and tobacco.

In the view of the regulated companies, the sector is lobbying, but excels in disclosing technical information to regulators. As for consumers, the regulated sector exerts strong pressure even at the highest levels of government, including in the process of appointing the agency’s new directors, which depends on Senate approval. Consumer representatives indicated some alternative means, but not used in isolation: the judicialization of decisions, and the postponement of decisions made by Anvisa’s Directors, at the request of the companies, which are equivalent to a veto strategy. Still, in their assessment, political interference often occurs through personal relationships. They cited, as a common example, the meetings between Anvisa directors and industry representatives at lunches during the break of events, which does not occur with consumers.

Chart 1. Synthesis of interviewees’ views on topics related to Anvisa’s interaction with stakeholders.

Source: author’s elaboration.

5. Discussion

5.1. Anvisa and the Insulation of Regulatory Agencies

A mark of insulation of regulatory agencies is pointed out as a trend resulting from the specialization of bureaucracies and characteristics related to the independence of the leaders (Sunstein, 1987). The essentially technical nature of the agencies, based on the regulation of specific and determined sectors, gives rise to insulation from their bureaucracies. In addition, it can be considered that the institutional design of regulatory agencies, which provides for fixed and staggered mandates for their directors, and the impossibility of ad nutum dismissal, are conditioning factors for greater insulation, in this case in relation to the government (Ramalho, 2007).

However, differently from what is expected by what the theory proposes, the analysis of the data collected in the research indicates that Anvisa presents a pattern of “deinsulation” of the State, represented by its various initiatives to expand the participation of society. These initiatives can be understood as a counterflow to the tendency towards bureaucratic insulation. At the same time, this pattern of offering mechanisms for agency interaction with stakeholders can be configured as an effort to affirm or acknowledge by society and government the arrival of a new institutional apparatus in the State (regulatory agencies) (Ramalho, 2007). In this regard, it is important to emphasize that Brazilian agencies, created recently from the State reform in the 1990s, carry a need to justify their independent nature, which entails a reinforcement of the explicitness of their control mechanisms for society. This may explain the support given by the agencies themselves for the approval of the General Law on Agencies (Ramalho & Lopes, 2022), which brings dozens of obligations for themselves, including the mandatory need to implement mechanisms for social participation at different times of the its regulatory process.

This institutional arrangement of agencies could also be characterized as a kind of mix between a dose of technocratic insulation and the increasingly consolidated tendency to exercise the notion of embedded autonomy. According to Evans (1995), embedded autonomy implies institutionalized links with industrial sectors, almost always excluding other social groups. The purpose of this arrangement is to promote the ability to establish external connections, via channels between the State apparatus and society, for the negotiation and implementation of policies.

5.2. How Stakeholders Manage to Influence Anvisa

Although there have been theoretical advances (Becker, 1983; Peltzman, 1976) over the original formulation of the capture theory (Posner, 1974; Stigler, 1971), the basic logic of the theory has remained the same: a chain of command starting in the market permeates central instances of the State, and leads to political actions implemented in regulatory decisions, which meet the interests of the original claimants, in general the industry (Moe, 1987). However, unlike the capture theory proposition, this research identified a behavior of stakeholders that prioritizes the direct relationship with regulators, through different types of interaction. The data collected show that stakeholders are frequently and systematically present in the official mechanisms of participation in the regulatory process of Anvisa.

In addition, the statements of industry and consumer representatives themselves recognize that these groups act according to a pattern of interaction that seeks dialogue and offer suggestions and contributions to regulators both in participatory mechanisms and in certain alternative means of interaction, as is the case of meetings with the Board of Directors and technical areas of Anvisa, and events organized by the stakeholders themselves. The use of the chain of command and control (predicted in capture theory) also occurs. But the search for certain actors, as a way of mobilizing principals (politicians in the National Congress and Government) to trigger agents (regulators)—as well as in the case of the judicialization of regulatory decisions, seems to be only carried out by stakeholders in specific contexts.

There also seems to be a tendency to counterflow this logic. A recent survey on lobbying carried out in Brazil (Santos et al., 2017) points out that, although interest groups operate more frequently in the environment of the National Congress, they act in multiple arenas. In addition to the Legislative, stakeholders mentioned that they also work with other public bodies, and among the relevant arenas they cite independent agencies as one of the preferred targets for their influence in the decision-making process. The survey also investigated what they called “lobby productivity” carried out in various policy arenas. In this theme, the effectiveness of obtaining positive results (influence) in the different areas of their performance was discussed with the stakeholders. Regulatory agencies appeared as the third most productive arena for the representation of interests, coming after the Legislative and the executive branches in general (Santos et al., 2017).

5.3. Police Patrol or Fire Alarm?

Although Brazilian regulatory agencies do not act under the tutelage of the Legislature and its commissions, the basic structure of the McCubbins and Schwartz (1984) model was considered useful to analyze the way in which Anvisa relates to the external public. Differently from what the authors propose, what is observed in the case of Anvisa (and other independent Brazilian agencies) is an emphasis on procedures related to “police patrol” control, and not on “fire alarm” control. Regarding regulatory agencies in general, there is a growing trend, over the more than 20 years since their creation, towards the structuring and consolidation of mechanisms for social participation, accountability and transparency (Pó & Abrucio, 2006; Ramalho, 2009a). This growth process has recently resulted in the definition of a varied set of mandatory resolutions for the creation and operation of participation mechanisms—aimed at the inclusion of stakeholders in the regulatory process—as well as periodic accountability activities to the National Congress and society in general (Ramalho & Lopes, 2022). In addition, it should be noted that the federal regulatory agencies themselves (including Anvisa) sought ways to strengthen support for the bill that contained measures to make public consultations and public hearings mandatory, among other forms of social participation in the regulatory process (Brasil, 2018).

Given this scenario, this research formulated two possible explanations, not mutually exclusive, for the support behavior of agencies to control mechanisms of the police patrol type. They are: 1) control of control: creation of institutionalized rules on the influence activity of stakeholders and its possible abuses (pressure) through the establishment of more predictable and stable mechanisms, with greater transparency and control by society; and 2) naturalization: making the influence of different stakeholder groups, dominated by industry, on the agency’s agenda, elaboration and decision-making process on regulations justifiable and acceptable. In the case of the first explanation, it is an attempt to reduce the possibility of excesses to be practiced by interest groups in the process of interaction with the agency, in order to assert their view on regulated objects. In the case of the second possible explanation, the agencies would consider the structure of pluralistic competition among stakeholders, in which the industry dominates, reasonable. In both cases of the explanations formulated, it is assumed that the agencies consider the action of external groups to influence their decision-making process to be inexorable. This assumption, if confirmed, contradicts the prediction provided by the literature on independent agencies regarding their tendency to insulation.

5.4. Asymmetric Influence among Stakeholder Groups

The analysis of the results evidenced an asymmetry of influence resulting from the competition process among stakeholders in Anvisa’s participation mechanisms. This asymmetry of influence is characterized by a comparative advantage of the industry, which dominates the mechanisms and stages of participation in the regulatory process, exerting greater influence on the agency’s regulatory decisions. This section presents a discussion of the different possible explanatory factors for this issue.

The size of groups

First, the organizational capacity factor must be considered. The comparative advantage of stakeholders in regulated sectors derives from their greater organizational capacity, due to their own nature and characteristics. This difference in capabilities is configured as an asymmetry of participation: those who are more organized and have more instruments, resources and time, have more access to participation mechanisms. That is, differences in the size, purpose and organization of groups result in the ascendancy of the politically stronger groups (Olson, 1965).

All groups of respondents recognized that there are differences in the opportunity for participation between different stakeholder groups. Regulators mentioned that the regulated sector has qualified staff dedicated to technically monitoring the issues in a consultation, unlike consumers, who have a lot of difficulty. In practice, companies and their representative entities are at Anvisa every day, participate in meetings, question measures and make suggestions. The regulated agents themselves clearly recognize the difference in opportunity, which is considered extreme by consumer representatives. Important related problems are the cost of participation (which includes, among other aspects, the availability of the interested party and sometimes their displacement) and the technical language used in matters subject to regulation by Anvisa. This view corroborates Stigler’s (1971) analysis of supply and demand for regulation, according to which industry will always benefit from state regulation, because smaller groups tend to be favored in the dispute with larger groups that have higher organization costs.

Internal coordination of groups

Another factor that can corroborate the analysis is intra-group coordination. According to the interviews, there seems to be a convergence between the opinions and modes of action of industry stakeholders, which may denote coordination between different actors and organizations of this interest group. This convergence can also be identified in the stakeholders of the consumer group. However, as the industry has a comparative advantage in terms of dominance in pluralistic competition, this dominance is reinforced by its own coordination capacity. Thus, intra-group coordination in the industry seems to act as a synergistic effect to leverage the strength of different actors and industry organizations in their power to influence the process and result of Anvisa’s regulation.

The interviews revealed a very consistent pattern of vision and action of industry stakeholders, verified in the responses of different representatives of this group. Industry representatives stated that they relate directly to Anvisa, prioritizing the activation of a chain of command and control that uses politicians to put pressure on the agency, in specific moments and contexts. They also mentioned that despite using all possible mechanisms officially intended for participation in the regulatory process, they prefer specific interaction mechanisms, such as meetings and events, where there is more proximity to the regulators. This strategy was confirmed by the regulators, who admitted that they are more susceptible to influence by this form of approximation.

Diversity of mechanisms and various stages of participation in the regulatory process

The multiplicity of participation mechanisms at Anvisa aims to obtain subsidies from the most different stakeholders interested in the objects under the agency’s regulation. However, contrary to what might be expected, this varied offer of mechanisms, at different times, ends up not strengthening and valuing the participation of all different segments in the regulatory process. This can be understood by the fact that the more structured and with more types of participation mechanisms is Anvisa’s regulatory process, paradoxically, one of the stakeholders (the industry) receives more incentives to exert its dominant influence on the agency’s decisions. Furthermore, this wide range of mechanisms and stages of participation can lead to the fragmentation of punctual efforts by stakeholders who compete with the industry for the chance to exert their influence on the regulatory process.

There are also different degrees of effectiveness of each mechanism for each group. It is a fact that there are mechanisms that are more adapted or friendlier to stakeholders with less organizational capacity (and consequently less instruments, resources and time). However, the different types of mechanisms do not have the same relative weight in Anvisa’s assessment of stakeholder participation. These different effectiveness of participation mechanisms favors the industry’s stakeholders, because Anvisa values more the participation and the result of those mechanisms that generate more proximity and deepening of the discussion, in other words, the specific interactions. And these mechanisms are more tailored to the needs and objectives of industry stakeholders.

As highlighted in Figure 2, the specific interaction mechanisms present greater proximity and deepening of the discussion, either because they are restricted to a few actors, or because they are carried out in person. Although the industry participates in all forms of participation, it is in these specific interaction mechanisms that the industry is more adapted and effective to pursue its needs and influencing objectives at Anvisa.

Stakeholder treatment isonomy

All groups of interviewees admitted that there is no equality of treatment given by Anvisa to the participation of different stakeholder groups. Anvisa gives more relative importance to industry contributions. In other words, in addition to the industry’s stakeholders having greater influence capacity, the structure defined by Anvisa for social participation mechanisms contributes to reinforce this

![]() Source: Author’s elaboration.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Figure 2. Specific interaction mechanisms highlighted among Anvisa’s social participation mechanisms.

dominance. Thus, in practice, the analysis and acceptance by Anvisa of the proposals of these different groups follows the asymmetry already identified in the interaction and capacity of influence that the different stakeholders have. This means that the segments that receive the most attention are the most influential, which means that in addition to having broader access to regulators, through various interaction mechanisms (especially the routine meetings with technical areas and directors of Anvisa), this interaction process is deeper, with greater quality and effectiveness. And as stated above, the regulated sector also has greater attention due to its greater capacity to influence, as this generates, in the view of regulators found in the interviews, a fear that Anvisa does not take into account the demands of companies and their representatives. In this view, when Anvisa opposes these interests, it can be cornered, lose power and even reduce its own ability to regulate.

On the other hand, despite the industry’s dominance in the dispute between stakeholders, consumers can also show some convincing power and marginal gains, especially in more sensitive topics, with great social appeal. These are the cases of certain regulatory decisions by Anvisa that clearly benefited more pronounced segments other than those related to the large regulated industry. Examples of relative consumer gains in the regulatory game corroborate Posner’s (1974) view, who analyzed case studies on the influence of interest groups on agency structures and procedures. For the author, state regulation is structured to benefit coalitions of regulated companies, but it can also include groups of politically effective consumers. In turn, Peltzman (1989) emphasizes that not only the industry can capture the regulatory authority, as the dominant coalition can also include some categories of consumers. Sometimes the government will not only respond to pressures from industry, as there is a tendency to maximize the regulators’ overall political utility in allocating benefits among interested groups.

6. Conclusions

The research was carried out to investigate how the regulatory game works in terms of the relationship between the interests of the groups and the influence exerted by each of them in a large and complex independent regulatory agency that regulates several relevant markets, with different stakeholders. To understand how the relationship between society’s participation and the formulation of regulatory decisions is processed, the concepts of interests and influence were used. It is understood that different groups have different interests and act strategically in different ways to influence decision makers. But it also matters how these demands are received and processed by regulators, and the complex relationships established within the public machine.

The research produced a broad set of results. Regarding participation mechanisms and stakeholders, Anvisa uses mechanisms that allow social participation since its creation, which represents a traditional mark of the agency. Since 2008, when it instituted the good regulatory practices program, the agency has been dedicated to improving its regulatory formulation and decision processes, including the guideline for promoting society’s participation. Anvisa’s great diversity of mechanisms has varied over time. The existence of stable mechanisms (such as the Public Consultation) can be noted, as well as mechanisms that have fallen into disuse (Sectoral Chambers), and others that are the object of recent innovations (Partial Early Consultation in the RIA Process). There is also a variety of multiple actors that are found in the different mechanisms of Anvisa, such as citizens, professionals, researchers, health regulators from subnational spheres, companies, and representatives of consumers and the regulated sector, among others. There is a relative distribution of these actors in the different official participation mechanisms of Anvisa, with a predominance of one or another sector.

Regarding the interviews with key actors, it was evident that there are different degrees of interest from the different stakeholder groups that were the object of greater depth in the research (industry and consumers). An important result obtained in the interviews refers to the different effectiveness of the mechanisms for different stakeholders. This has a relevant impact on the outcome of the regulatory process. A second result, which also drew attention, is the recognition, by all groups of respondents (including regulators), that Anvisa does not grant equal treatment to different groups of stakeholders. Finally, another result considered relevant is that the priority strategies used by stakeholder groups for their influence prioritize certain forms of interaction that are not Anvisa’s formal mechanisms for the social participation of stakeholders (such as meetings and events, for example).

The discussion of the results pointed to a series of conclusions on four main themes. Initially, it can be concluded that there is no significant isolation of the agency in relation to the stakeholders. Differently from the theory about the insulation of specialized bureaucracies (Sunstein, 1987), what was noticed in this research is that Anvisa has marked traces of insulation. In addition, it has a behavior that adheres to the concept of embedded autonomy (Evans, 1995). The data collected demonstrate a constant and systematic process of interaction between Anvisa and the external public, notably with certain groups of stakeholders. The analyzes also point to a more consolidated link between the agency and business sectors of the industry included in the research, to the detriment of other stakeholders who also interact and participate in the mechanisms of the regulatory process, and eventually benefit from their decisions, such as the consumer’s case.

Another conclusion, different from the capture theory proposition (Becker, 1983; Moe, 1987; Peltzman, 1976; Posner, 1974; Stigler, 1971), is that stakeholders use as a priority the direct relationship with regulators, through official mechanisms, as well as through the use of alternative strategies (such as meetings and technical events). This may point to a new pattern of public-private interaction in the regulatory field, in the still short institu-tionalization of Brazilian independent agencies. In just over 20 years of existence, Anvisa has shown a growing appreciation of dialogue with the external public, which can raise the confidence of interested groups and give rise to their inflection of priorities for action. This new scenario, still under consolidation, points to a new form of interaction between regulators and society, with increasing stakeholder interest in agencies (Santos et al., 2017).

A third conclusion is that the structuring and consolidation of mechanisms for social participation (and accountability and transparency), over the 20 years of Anvisa, institutionalized a pattern of systematic and comprehensive control of the “police patrol” type. This type of control seems to be the rule in independent agencies in Brazil (Pó & Abrucio, 2006; Ramalho, 2009a), and not the “fire alarm”, as indicated by McCubbins and Schwartz (1984). This scenario was recently crystallized in the General Law on Agencies (Ramalho & Lopes, 2022), which seems to indicate a preference by regulators for the systematic influence of stakeholders in their regulatory process, as the approval of this Law had the declared support of the federal regulatory agencies themselves (including Anvisa).

Finally, it was concluded that at Anvisa there is an asymmetry of influence between the stakeholders, in which one of the groups (the industry) has a dominant position over the others. It was possible to identify four reasons for this result. The ability to organize groups, according to Olson (1965), generates a comparative advantage of the industry in relation to other stakeholders in the pluralist dispute to obtain regulatory benefits. This conclusion corroborates the prediction of the economic theory of regulation by Stigler (1971) according to which the demand of the industry for regulation will benefit from the offer of state regulation by independent agencies. Another factor is coordination among industry members. Despite the possibility of having internal coordination in other stakeholder groups, coordination within the industry group acts as a synergy that leverages the individual strength of actors and organizations to increase their relative power of influence in the regulation carried out by Anvisa. A third factor is the diversity of Anvisa’s participation mechanisms which, paradoxically, exerts an incentive to exercise the dominant influence of the industry in the agency’s decisions. This diversity also seems to dilute other stakeholders’ attempts to influence them. A final factor that explains the industry’s dominance is Anvisa’s lack of isonomy in the treatment of different stakeholder groups. Anvisa values more the participation mechanisms that generate specific interactions, in which the industry is more adapted and effective to pursue its needs and achieve its influence goals at Anvisa.

The conclusions point to a new view on the relationships established between stakeholders and regulators, in the case of the investigated agency. Often, what was verified in the obtained data was a different scenario from what could be expected, based on what the theory proposes. It is considered that the conclusions can be useful for a new and better understanding of the dynamic relationship between stakeholders and regulators, inside and outside the official participation mechanisms of an independent regulatory agency. It was noteworthy that certain institutional structures and processes—intended to promote the expansion of the participation of different actors—result in the deepening of the concentration of influence power of a certain dominant group. The conclusions clearly point to a complex scenario of interaction between interest groups and state agents, in order to highlight new strategies of influence and behavior of stakeholders.

Finally, it is important to note that this research has a limited scope, especially given that it was limited to the specific case of an independent agency. Thus, the investigated theme deserves further deepening for the expansion of research subjects.