1. Introduction

Imagine standing in a pitch-black night, under the caliginous sky, stranded in the woods with no one but the eerie gust of wind and the occasional rustle of leaves to save the imminent danger about to happen. Suddenly, there’s a sound looming from behind and it just so happens to be footsteps, appearing out of thin air, and as they grow closer, fear starts to settle in. The conventional public considers this to be a classic example of fear. Yet, many don’t realize that fear appears through other forms as well: heights, failure, insects, dark, etc.

Fear of failure (FF) is a recurrent fear throughout teens, chiefly due to the distress associated with high school and its following repercussions. Individuals with a high FF delineated less self-confidence with and direct relationship to shame upon themselves (McGregor & Elliot, 2005). On the contrary, a build-up on the previous statement asserts that FF is influenced by the academic process that results in anxiety and low resilience to learned helplessness (Martin & Marsh, 2003). The lack of involvement in school is also an issue dominating teens’ psychological well-being such as an increase in FF (Caraway et al., 2003). According to Dr. Yunus (2014), Assistant Professor of Sociology, factors of suicides among teens can be traced academic pressure and FF. The popular idea of FF appears to have dire repercussions on teens considering their towering pressures and expectations. Unable to express their thoughts due to expectations from family, friends, teachers, and the society, teens suffer tremendously with the additional burden of failure and the fear that follows it. This study is to examine that phenomenon personally through high schools in large suburban school districts in North Texas.

FF is analogous to the appearance of shame (Gómez-López et al., 2019). Furthermore, teens are faced with being made fun of (Eitzen, 2016) and thus experiencing embarrassment from it (Ellison & Partridge, 2012). Due to an FF, teens experience a drop in self-esteem with an inverse relationship to stress and anxiety (Moreno-Murcia & Conte, 2011). It, additionally, directly reduced personal fulfillment or self-satisfaction (Gustafsson et al., 2017).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definitions

To clarify some terms, FF was defined for this particular study as a fear of not living up to certain expectations or standards placed on the teens. This is professionally known as atychiphobia which is not a mental disorder, but rather a persistent FF that affects daily life. Decisions were clarified as statements or conclusions made by someone which for this study will be solely focused on statements or conclusions made by the teens.

2.2. Fear in Daily Life

Conventional wisdom has it that fear has significant negative effects for the overall population. In discussion of fear, a particular study by Samantha Artiga and Petry Ubri (2017)—both professionally adequate in business and health—gathered data on how fear of living among immigrant families in America has influenced daily life, well-being, and health. Significant evidence includes “behavioral changes, such as problems sleeping and eating; psychosomatic symptoms, such as headaches and stomachaches; and mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety” among immigrant children (para. 6). Furthermore, “fears are negatively affecting children’s behavior and performance in school” (para. 6). Most importantly, the detrimental consequences on health in the long-term on children. Pre-existing studies are also strongly mentioned as further support of fear damaging effects on physical and mental health while also exacerbating children’s growth and development. This evidence supports the general conclusion that fear has harmful influences on the population. Although the population in this particular study was immigrant families, the research applies to fear overall and its effects on the well-being, health, and daily life of, specifically, children. Additionally, Cox (2009) conducted a semester-long study from students and instructors at an English course in a community college. The researcher was investigating the correlation between the possibility of failing college and fear of failure impact on students’ behavior. The results conclude that students have a have a higher chance of undermining their educational goals if they lack help and intervention from instructors or the college.

Similar research advances on the previous research, reinforcing the ideology that fear, especially fears of conventional objects or things such as heights or insects, would have an onerous impact on daily life as well as causing additional stress (Wexler, 2013). Failure is a common occurrence throughout teens and based on the understanding brought by Wexler’s research, FF could distract their daily life and rattle them medically.

3. Fear of Failure

As Richard G. Beery (1975), a Counseling Psychologist at UC-Berkeley, discusses it, “[m]any students suffer in the educational process” (p. 191). Beery refers to how numerous students experience school-related problems and as a result, are faced with a FF or in many cases, not living up to certain expectations that are placed on them. In other words, FF in society has repercussions on teens due to its effects on their decisionmaking process. These effects cause teens to make poor and regrettable choices, not only affecting them in the near future but also their family and friends.

FF in society is a common attribute and many students subconsciously get affected by it. Authors Correia, Rosado, Serpa, and Ferriera (2007), all affiliated with the University of Lisbon in Portugal, come together to detail a study on Portuguese athletes by exploring how FF correlates to burnout, drop-outs, stress, and anxiety among those athletes. In another journal by Ellen Rydell Altermatt, a developmental psychologist, and Elizabeth F. Broady, an author who’s done multiple studies on psychology, there is a detailed overview on the anxiety, fears, and phobias among children with autism spectrum disorders in order to inform the public or parents of how to help their children overcome fears. Both these articles point out how unique individuals such as the Portuguese athletes and the children with autism spectrum disorders both experience FF. This certifies that FF does not have a specific group of people that it clings onto but is rather based on the individual themselves and can occur to anyone.

Similar to the study on Portuguese athletes, Gonzàlez-Hernàndez and his collaborators wrote a peer-reviewed article with the intent of informing the public about the correlation between commitment and FF among 479 handball players between the ages of 16 to 17. This study analyzes a different approach to the FF through the use of Performance Failure Appraisal Inventory (PFAI) and other forms of methods. The authors’ main goal was to evaluate the role of FF in the correlation between burnout and sport commitment resulting in FF being a cause for burnout among athletes and a source of “depersonalization, reduced sense of personal accomplishment, and emotional exhaustion” (para. 21). FF is represented as an unwelcome influence on teens with the incorporation of successful methods for the objective of this study.

A parallel analysis is brought by Conroy and his associates (2010)—all acclaimed in health with PhDs in Kinesiology and employed as a Mental Health Consultant or Professors at Penn State. This study was conducted on 544 college students and incorporates the PFAI and other forms of measures in order to determine the consequences of FF. The results presented by the PFAI support the ideas presented by the previous investigation as the consequences of FF encompass shame, drop in self-esteem, uncertainty, worry, anxiety and cognitive disruption.

A new perspective catenating to the aforementioned evidence is brought by an examination of FF based on parental practices by authors Sagar and Lavallee (2010), engaged in the Department of Psychology and Sport and Exercise Science respectively. They deduce that a child’s FF is actively heightened due to parents’ negative responses to failure. Parents play the judge in child FF, dictating it through expectations and pressures concreted into them and pressures thrown on them.

Diametrically opposed to all the previously mentioned research, Martin and Marsh (2003)—both Educational Psychologists—aver that FF can occasionally be ¨friend”. Given this information, it is possible FF might have positive impacts. In spite of this, Martin and Marsh revert back to the recurrent claim deciding that FF isn’t acceptable but merely has moments where individuals could make out something decently beneficial out of it.

Moreover, Benson and his coworkers (2022), a part of the Department of Psychology, are directly germane to Martin’s and Marsh’s findings yet advance on it further disputing that although FF does lead to depression, at times, it provides wisdom. The objective was to develop positive outcomes from failure through an online study on 208 participants. In summary, FF was seen to show both positive and negative outcomes, agreeing and disagreeing to pre-existing research by declaring truths ignored, not considered, or not even debated about.

3.1. Gap

Current research on FF and atychiphobia included numerous studies on individual topics such as expectations, FF, and decisionmaking. Auxiliary pre-existing studies consisted of decisionmaking and the constituents that altered them. However, there weren’t any pre-existing studies that tethered one of the main factors of my research to the other two: decisionmaking. There has been research studying the interdependence between expectations and FF, enough to get a background understanding of the topic but not enough to make resolute conclusions. This was the foremost rationale to choose this topic in order to figure out the correlation that exists between expectations, FF, and decisionmaking. This correlation is paramount as it can provide teens an understanding of the basic symptoms of FF and the negative ramifications of it. This can further urge teens to avoid it and possibly find alternate mechanisms to cope with stress and anxiety instead of developing a FF, or worse atychiphobia. The ongoing debate on whether FF has positive or negative repercussions and the psychology surrounding fear was especially inspiring to investigate in this area. In order to diagnose the current gap between expectations, FF, and decisionmaking, the focal research question is: To what extent does FF caused by expectations influence teen decisionmaking in large suburban school districts in North Texas?

3.2. Hypothesis

The initial hypothesis for the turn out of this study was that FF would cause a negative impact on teen decisionmaking. As presented in the literature review, the broad extent of this topic of area fixated on the detrimental facets of FF driving the hypothesis to be analogous.

3.3. Summary

The Literature Review summarizes claims made on fear of failure and their relation to students. Although there were contradictions, the general trend of previous researchers was that FF has a negative influence on teens. The hypothesis for this study followed the pattern of previous scientists and psychologists by following the trend that FF ruins teen’s decision making. The gap is the three factors of this study—expectations, FF, and decision making—never being explored and studied together.

4. Method

4.1. Study Design

The purpose of this study is to figure out if fear of failing in society influenced by expectations affects the decisions teens between 13 and 18 make. This is impactful to teens in that an understanding of fear and its negative effects would give teens a reason to avoid the symptoms of it. These methods are the best for this study as the data being collected was predominantly qualitative and requires careful analysis. Data was evaluated through explanatory analysis which is perfect for a study that hasn’t been conducted before and needs to be explored using pre-existing research and the data gathered. This data analysis promotes the process of exploring a topic that has no notion of the relationship being examined. This is ideal for this study as FF and decision making has not been discussed before. It requires developing connections and formulating hypotheses since it’s a topic that has not been considered hitherto. It needs this type of analysis to explore the gap existing in this field of study.

A mixed quantitative and qualitative survey was conducted. Both quantitative and qualitative were necessary to grasp the overall statistics as well as the expanded reasoning forsome of the one-dimensional questions asked. Furthermore, an effective combination of quantitative and qualitative questions allowed for a “better organized understanding of the results” (Lee & Smith 2012). As shown in the literature review, an innumerable count of studies conducted observational studies whether that be evaluating conversations or observing individuals through a set time period. The study that was most significant and similar to this research is González-Hernández and his associates’ exploration of FF teen Spanish handball players (2021). The participants’ ages in this study were fortunately similar to the majority of the subjects in this research with all of the lying between the ages of 16 and 17. Although the objective focused on sports, vastly opposite to decision making, the main research was precisely studied on FF. This study was the foremost effective research to base this paper off from as it was the closest to the purpose of this paper among the few contenders. It provided a multitude of sources to delve deeper into FF. The study utilized a questionnaire with Likert-scale questions springing the idea for the incorporation of those types of questions in the survey used for this research.

In order to eliminate considerable factors that can play into causing FF, the first few questions asked, along with the participants’ ages, were based on expectations placed on the participants. Following that, participants were questioned if they’ve ever had a fear of not living up to those expectations, defined for this study as a FF. To answer the research question, participants were then finally asked how FF has disturbed their decision making. This was evaluated to determine if FF has affected them or not and if it has, whether that was positive or negative. Figure 1 showcases this procedure.

4.2. Participants

Participants were required to be between the ages of 13 and 18 and a part of the large suburban school districts in North Texas. This demographic was categorically chosen as teens are conventionally subjugated to a FF through school

![]()

Figure 1. Order of questions asked in the survey.

expectations and performance (Artiga & Ubri, 2017). Besides, teens were among the ones with wide-ranging pre-existing studies that granted increased comprehension and concrete conclusions to be made. The survey was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) denoting that participants were anonymous and free to leave whenever during the survey. This also ensured the ethicality of the study design and practices. The survey was sent out to the large suburban school districts in North Texas with Informed Consent Forms on hand (see Appendix A). This garnered a total of 41 participants partaking in the survey.

4.3. Research Instruments

Quantitative data was collected through multiple choice questions with answer choices consisting of yes, maybe, and no. These questions were essential to grasp the general trend. They also allowed for easier analysis and splitting up of the participants into groups on certain questions. Additionally, the use of Likert scale questions also known as Ordinal questions enhanced and expanded on the previous multiple choice questions. Also, multi-select questions (M-S questions) granted the participants to select more than one answer choices in case there were a multitude of choices that applied to the question. This was effective to grasp the relationship between the choices and to examine which is the most common among the participants. Last but not least, qualitative data was collected through explanatory and descriptive questions permitting the participants to expand on their thinking of the other questions through open-ended responses.

The first few questions evaluated the expectations placed on the participants. This part was essential to recognize which portions of the participants were under pressure through expectations. Albeit, it did supply a smooth transition for asking the subjects if they have a fear of failure. Table 1 summarizes the questions asked on the survey about the expectations placed on the participants.

The next set of questions jumps into fear of failure. The way of asking the question, however, was by asking them if they had a fear of not living up to the expectations placed on them. However, as aforementioned, this was clarified as the clear definition of fear of failure for this particular study. The only reason for

![]()

Table 1. Questionnaires on the expectations placed on the participants.

phrasing the questions this way was to enforce that the participants answered the questions truthfully without feeling emotionally disturbed through explicitly saying “fear of failure”. It was also to eliminate response bias and ensure that participants who don’t particularly understand the definition of fear of failure as elucidated for this study would be capable of responding to the questions properly. The question on fear of failure is stated in Table 2.

Table 3 demonstrates the questions that asked the general effects fear of failure has had on the participants. The responses for these questions were efficacious in indicating the possible long-term effects not considered at the onset of the research process.

Finally, Table 4 exhibits the effects of fear of failure on decision-making which is the main objective of this research. Considering that the survey was formatted to ensure that fear of failure was influenced by expectations and not any other factors, the results on decision-making are valid to assume that they were influenced by fear of failure caused by expectations.

![]()

Table 2. Questionnaires on the fear of failure in the participants.

![]()

Table 3. Questionnaires on the effects of fear of failure in participants.

![]()

Table 4. Questionnaires on the effects of fear of failure on decision-making in participants.

4.4. Data Analysis

González-Hernández and his colleagues (2021) use means and bivariate correlations as a form of evaluation. These methods were adopted for this research as well which inclined the concreteness of the conclusions and made evaluation far effortless and efficacious than alternative forms of assessment.

Forty-one participants partook in the survey. Consent forms were accessible on hand. To guarantee confidentiality and truthful answers from the participants, consent forms and the survey informed participants their names will not be disclosed and they will be anonymous throughout the entire research process. The words “participants” and “subjects” are used interchangeably. The survey and study design were approved by the Institutional Review Board to ensure ethicality.

5. Results

Survey Results

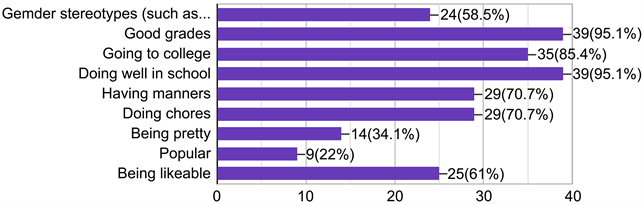

The questionnaire (see Appendix B) was taken by 41 participants. As previously mentioned, questionnaires on expectations were asked first to eliminate any factors from skewing the evidence and conclusions. Figure 2 reveals the results for when participants were queried if they’ve had expectations placed on them. Almost all participants professed they did with the rest claiming “maybe”. In essence, most of the participants might have experienced at least a momentary passing of a fear of failure from those expectations. Participants, additionally, asserted what expectations were placed on them through M-S questions. Among them, getting good grades and doing well in school ranked the highest with going to college, having manners, and doing chores following closely after them (see Appendix C). In the open-ended question, asking the same question, responses were: “tak[ing] up opportunities in the community”, “giv[ing] more to others”, and “[s]etting an example” (see Appendix D for all the responses). Everyone had expectations placed on them by their parents with friends and teachers coming in right after (FigureE1). Figure 3 exhibits how much the expectations placed on the subject have affected them through a Likert scale question with 1 being “Not at all” and 10 being “A lot”. The graphical representation of

![]()

Figure 2. Responses when participants were asked if they’ve had expectations placed on them (Answer Choices: Yes, Maybe, No).

the responses is skewed left, attesting that most of the participants were highly influenced by the expectations placed on them.

However, FigureE2 demonstrates a different approach on how much subjects felt they were feeling restricted due to the expectations placed on them. The graphical display of this was unusually contrasting to the graph of how much expectations have affected the participants (Figure 3). An M-S question querying the participants on who precisely has supported them. The results were oddly similar (Figure E3). Similarly, the Likert-scale projecting how supportive people around the participants were (FigureE4) was akin to Figure 3. FigureE4 shows a symmetric or uniform display on the very end of the Likert-scale, between 5 - 10, which is a much more drastic version of Figure 3. Additionally, the average for FigureE4 lies at 7.927, a bit larger than the average of Figure 3 at 7.780.

A comparative chart between level of fear of failure and level of effect of expectations is demonstrated through Figure 4. The x-axis represents the Likert-scale with 1 being the lowest level replicating “Not at all” and 10 being the highest replicating “A lot”. The y-axis constitutes the number of students who chose that particular number on the Likert-scale. A graphical representation of two graphs clarifies the relationship between them. There appears to be a positive, moderately strong, decently linear relationship with no significant outliers between the level of fear of failure and the effect of expectations on the participants. There are gaps in certain areas, which can be presumed to be due to

![]()

Figure 3. Responses when participants were asked how much expectations have affected them (Likert-scale Question: 1-Not at all; 10-A lot).

![]()

Figure 4. Comparison chart between fear of failure and effect of expectations (Likert-scale Question: 1-Not at all; 10-A lot).

response bias as there wasn’t a significantly large sample. The general trend expresses that as the level of effect of the expectation increases, the level of fear of failure generally increases as well.

Among the participants, 16 and 17 year-olds were the largest portion of participants (see FigureE5). As this group are considered sophomores and juniors, usually known as the hardest years of high school, that would’ve skewed the results but the percentage of participants who claim they have a fear of failure is at a sweeping 78%, shown by Figure5. Thus, even if the participants were allocated more to younger groups as well, results and conclusions would have been relatively the same as the statistics are considerably high.

FigureE6 illustrates another Likert Scale on how vast the fear of failure was for the participants. This graph is undoubtedly skewed left with the peak at a 10 conveying that a considerable amount of the participants are perturbed by an extensive fear of failure. The mean was at 7.575, a number lying on the second half end of the Likert-scale. Another comparative graph is Figure6 correlating the relationship between fear of failure and impact of the fear of failure on the participants. The x and y-axis are just like Figure4. The correlation for this graph is much stronger than Figure4 with a positive, strong, decently linear relationship with no outliers. The comparison presents that as the level of fear of failure increases, the impact of it increases simultaneously.

Now, once the survey was done asking whether participants had expectations placed on them or had a fear of failure, the next portion was the impact of fear of failure on the participants. The first few questions in this section were just general effects. One of the questions was to observe the population in a one-dimensional question through the answer choices: yes, maybe, no. This question simply queried whether subjects were even affected by a fear of failure (FigureE7). Most of the participants were impacted by it (82.5%). FigureE8 delves deeper into the one-dimensional question through a Likert-scale. The

![]()

Figure 5. Responses when participants were asked if they’ve ever had a fear of failure (Answer Choices: Yes, Maybe, No). Note. This question was phrased by asking participants if they have had a fear of not living up to the expectations instead of specifically using the words “fear of failure”. In order to avoid confusion, this was the most reasonable method to accommodate participants to fully understand the question through a smooth transition from the questions on expectations and to get them to answer truthfully without any bias due to wording of the question. Participants were later informed with the definition of fear of failure as described for this study.

![]()

Figure 6. Comparison chart between fear of failure and effect of expectations (Likert-scale Question: 1-Not at all; 10-A lot).

peaks were at 9 and 10, the highest on the scale, exposing that a noteworthy fragment of the subjects were greatly affected by a fear of failure. One thing to note is that this question does not pointedly state whether participants were positively or negatively influenced by the fear of failure. Participants were further asked on the specific effects caused by a fear of failure. The first of the questions was a M-S question shown by Figure 7. Almost all participants (95%) have experienced stress from a fear of failure with the next leading ones being self-doubt and anxiety. In an open-ended question asking the same question, some responses included feeling scared for the future, “[n]ot being happy”, and “[c]rippling mental illnesses” (see Appendix F for all responses).

Appendix G and H evaluate the effects of fear of failure on decision-making. One of the questions was another one-dimensional question simply asking if the participants changed their decision by a fear of failure (Appendix G). The following question was an open-ended question to get personalized responses from the participants (Appendix H). This format, with a closed-ended question and open-ended question, was replicated when querying the participants about the effect of fear of failure negatively and positively on their decision-making. A hefty amount of the participants averred that a fear of failure has changed the decisions they have made as more (Appendix G). It affected their decision-making through being more careful, studying more, and changing who they are to be someone else (Appendix H). Although the results were fairly akin to each other, 43.6% said they have not made bad decisions due to a fear of failure while only 30.8% responded “Yes” (Figure 8). Specific responses in the open-ended questions were: “being someone I’m not”, “Hurting myself”, and “Give up when things get too hard” (see Appendix I for all responses).

The most shocking aspect of this study is manifested through Figure 9. It directly contradicts the hypothesis for this study and required further research into this topic to comprehend this phenomenon. Almost half of the subjects replied that they did make good decisions (Figure 9). The open-ended responses were exceptionally beneficial to apprehend this unforeseen circumstance (see Appendix J). Most common recurrent responses were working harder, prioritizing studying, and following their parents more.

![]()

Figure 7. Responses when participants were asked the effects of fear of failure (M-S Question).

![]()

Figure 8. Responses when participants were asked if they’ve made bad decisions from a fear of failure (Answer Choices: Yes, Maybe, No).

![]()

Figure 9. Responses when participants were asked if they’ve made good decisions from a fear of failure (Answer Choices: Yes, Maybe, No).

6. Discussion

6.1. Findings

Based on the results, all the participants experienced expectations demanded from them as there weren’t any participants who said no. School expectations were the most recurrent germane to the facts that, for children, “receiving poor grades and encountering problems with homework are among the most common distressing events in their daily lives” (Altermatt & Broady, 2009: p. 454). Academic procrastination is also a significant influence on FF (Zarrin et al., 2020). Hence, academic stress appears to be a high deciding factor of FF. FigureE2 was less skewed left and more symmetric than Figure 3 unveiling that although expectations did affect the participants, they didn’t consider the effects to be negative as they didn’t feel they were as restricted by them. Parents were the main source for these expectations (FigureE1), which mirrors Sagar and Lavallee (2010) who stated that FF is negatively developed due to pressures and expectations placed by parents confirming that parents are one of the leading background influencers of FF. Yet on the same page, parents were also among the most supportive (Figure E3). This phenomenon indicates that the people around the participants play a double role, like two sides of the same coin. Accordingly, the results displayed that the participants actually felt that the support they received was higher than the effect the expectations had on them dictated by the mean of FigureE4 being slightly higher than the mean of Figure 3 (7.927 > 7.780). This brings a new light and a counter argument into the topic of study on teen expectations which, as shown by the literature review, generally focus on expectations and their negatives, never considering teens receive support, as well, from friends and family.

In spite of that, the peak of the participants had a high FF due to expectations, especially since the average Likert-scale number laid in the higher end (

= 7.575) (Figure E6). Figure 4 depicts the general trend was that as the effect of expectations increased, the FF increased as well, affirming there was a correlation between them.

In this respect, the correlation between FF and the level of FF and the impact of it was very high. Thereby, as the FF escalates, the effect of it on the teens grows proportionally. Albeit, whether the impact was positive or negative was not determined through this graph.

To answer the research question, most teens were impacted on their decision-making by an FF caused by expectations as more than half (68.4%) of the participants claimed it did (Appendix G). Hence, the open-ended responses were principally significant as they provided evidence not hypothesized hitherto. As Martin, Marsh, Benson and his colleagues disputed, there were indeed positive effects of fear of failure. Almost half (48.7%) insisted they made good decisions from an FF, explicitly disproving my hypothesis. From the open-ended responses (Appendix J), it was understood that FF forced teens to study more, work harder, inspire them to do better and like Benson and his associates deemed, it provided a form of wisdom.

Nonetheless, the preeminent factor not acknowledged was that participants were still severely negatively affected by FF. When asked what effects FF has developed, a crucially high percentage (95%) responded with stress. Anxiety and self-doubt were additionally high supporting the idea that youth are greatly disturbed by anxiety disorders (“DON’T WORRY! THERE IS A WAY”, 1986). It’s as if the teens were under an illusion and didn’t realize this has actually been affecting them negatively in the long run even if they do believe this fear is a positive influence at the moment. These effects could have been the long-term effects of a fear of failure they’ve had quite a few years ago because the survey didn’t necessarily ask them if they have a fear of failure now especially since there were many who referenced FF and decisions made in past tense. The most likely reasoning for this phenomenon would be that the teens suppressed their feelings in a way that caused more stress and anxiety in the future leading to problems such as depression or medical concerns (Benson et al., 2022). Thus, although there might be short term benefits for a few teens from a fear of failure caused by expectations, in the long run, there is a huge possibility that teens won’t be impacted the same way.

6.2. Fulfillment of Gaps in Research

This research addresses the gap between expectation, FF, and decision-making among teens. In pre-existing studies, FF was connected to sports and academics yet a correlation to decision-making has not been evaluated. This research study dissolves that gap but evokes a new one in its place. Researchers can use this study as a base or understanding to evaluate the gap dwelling among FF and its long-term effects.

6.3. Limitations

Due to limited time, there were a few hindrances that unlatched from it. Additional participants would’ve allowed for more concrete conclusions. There were certain areas where it was unsure to make solid deductions due to passive data that could have been resolved with extra participants.

Furthermore, questionnaires on the long-term effects were not explicitly asked during the survey as the hypothesis and previous research did not provide significant context to predict that long-term effects would play a crucial role in this research. Fortunately, there were a modest portion of questions that did allow a prediction to take place about long-term effects playing a factor yet concrete conclusions were not able to be made in that regard. Had I asked questions pointedly on whether FF has positively or negatively influenced the participants in the future or conducted an observational survey throughout a time period of a couple of months, that would’ve permitted accurate inferences to be constructed.

The use of the PFAI would have been compelling to the research as it’s a highly effective method in this field of study. The combination of PFAI with the method used would’ve provided stronger conclusive evidence on the exact level of effects of FF. It would’ve provided a deeper and fruitful understanding of effects of FF which this paper heavily relied on.

Response bias must be acknowledged as well. Lying and misleading responses might have hindered aspects of my conclusions. Follow-through experiments/studies or another conduction of this research would solidify the hypotheses resulting from this research to be clarified and new data and resolutions to be shined a light.

6.4. Implications

A meaningful display of this research is best showcased through teens. This study establishes the negative consequences teens could face in the near future. Once the veil is uncovered and the illusion that FF is benefitting these teens is replaced with a knowledge of the detrimental impacts of fear, teens, possibly their parents/guardians as well, are able to smoothly take an initiative to prevent the unpleasant effects from creeping up. This would dedicate teens to approach a new method to improve their lives instead of being manipulated through fear. Moreover, as this research contradicts pre-existing studies and the common stereotype, researchers studying fear would be able to use this study as a counter-argument or as a push to further investigate this topic. This area of interest is filled with research providing unique arguments that agree and disagree; thus, this study appends to current debates. Plus, as this research investigates a specific phenomenon not thought about before, other researchers could be roused to conduct their own studies to expand this individualistic topic as well as extract deeper secrets and in-depth findings. The gap that still exists with the long-term effects can provide a space for researchers to probe into and be a factor for them to consider when scrutinizing their evidence. Also, these findings captivate teens since it disproves their mindset on FF and gives a newfound understanding of how fear is infecting them and discretely altering them medically and through their decision-making.

Appendices

Appendix A

Informed Consent Form

INDEPENDENCE HIGH SCHOOL

CONSENT TO BE PART OF A RESEARCH STUDY

A1. Key Information about the Researchers and This Study

Study title: Fear of Failure and Its Impacts

Principal Investigator: Sumali Junuthula, High Schooler, Independence High School

Faculty Advisor: Candice Sinclair, Independence High School

You are invited to take part in a research study. This form contains information that will help you decide whether to join the study.

Taking part in this research project is voluntary. You do not have to participate and you can stop at any time. Please take time to read this entire form and ask questions before deciding whether to take part in this research project.

A2. Purpose of This Study

The purpose of this study is to examine the effects that fear of failure caused by social expectations has on a teen’s decision making. Teens have a high sense of fear of not living up to expectations set by parents, peers, and society. This study will draw the correlation between this sense of fear and how they might make different decisions.

A3. Who Can Participate In the Study

1) Who can take part in this study? In this study, teens between the ages 13 and 18 will participate. Furthermore, only teens in the Frisco District can participate in this study.

A4. Information about Study Participation

1) What will happen to me in this study? A survey will need to be taken and nothing more. The survey questions might trigger the participant. Certain questions will ask about social expectations placed on them, how that has caused a fear of failure, and if it has affected their decisions.

2) How much of my time will be needed to take part in this study? A onetime survey is all that is needed. The survey will take approximately 5 to 10 minutes and not any longer.

A5. Information about Study Risks and Benefits

1) What risks will I face by taking part in the study? What will the researchers do to protect me against these risks?

The survey is anonymous so personal information or information that will identify who they are will be shared with the investigator or anyone else. There is no risk to the participant in partaking in this study.

You do not have to answer any questions you do not want to answer.

2) How could I benefit if I take part in this study? How could others benefit?

You may not receive any personal benefits from being in this study. However, others may benefit from the knowledge gained from this study.

A6. Ending the Study

1) If I want to stop participating in the study, what should I do?

You are free to leave the study at any time. If you leave the study before it is finished, there will be no penalty to you. If you decide to leave the study before it is finished, please tell one of the persons listed in Section 9. “Contact Information”. If you choose to tell the researchers why you are leaving the study, your reasons may be kept as part of the study record. The researchers will keep the information collected about you for the research unless you ask us to delete it from our records. If the researchers have already used your information in a research analysis it will not be possible to remove your information.

A7. Protecting and Sharing Research Information

1) How will the researchers protect my child’s information?

Research data is collected anonymously so none of your child’s information will be needed and none of the questions require answers that will identify your child.

2) What will happen to the information collected in this study?

We will keep the information we collect about your child during the research [for future research projects/for study recordkeeping or other purposes (describe)]. Your child’s name and other information that can directly identify your child will be stored securely and separately from the research information we collected from your child.

A8. Contact Information

Who can I contact about this study?

Please contact the researchers listed below to:

· Obtain more information about the study

· Ask a question about the study procedures

· Report an illness, injury, or other problem (you may also need to tell your regular doctors)

· Leave the study before it is finished

· Express a concern about the study

Principal Investigator: SumaliJunuthula

Email: sumali.junuthula.900@k12.friscoisd.org

Phone: 469-407-0337

Faculty Advisor: Gabrielle Candice Sinclair

Email: sinclairg@friscoisd.org

Phone: 469-633-5400

If you have questions about your rights as a research participant, or wish to obtain information, ask questions or discuss any concerns about this study with someone other than the researcher(s), please contact the following:

Candice Sinclair

AP Research Instructor (FISD)

sinclairg@friscoisd.org

A9. Your Consent

Consent/Assent to Participate in the Research Study

By signing this document, you are agreeing to be in this study. Make sure you understand what the study is about before you sign. I/We will give you a copy of this document for your records and I/we will keep a copy with the study records. If you have any questions about the study after you sign this document, you can contact the study team using the information in Section 9 provided above.

I understand what the study is about and my questions so far have been answered. I agree to take part in this study.

Print Legal Name: ________________________________________________

Signature: _______________________________________________________

Date of Signature (mm/dd/yy): ______________________________________

Parent or Legally Authorized Representative Permission

By signing this document, you are agreeing for your child’s participation in this study. Make sure you understand what the study is about before you sign. I/We will give you a copy of this document for your records. I/We will keep a copy with the study records. If you have any questions about the study after you sign this document, you can contact the study team using the information provided above.

I understand what the study is about and my questions so far have been answered. I agree for my child to take part in this study.

__________________________________________________________________

Print Participant Name

__________________________________________________________________

Print Parent/Legally Authorized Representative Name

Relationship to participant:

· Parent

· Spouse

· Child

· Sibling

· Legal guardian

· Other

__________________________________________________________________

Signature Date

Reason second parent permission was not collected:

· Parent is unknown

· Parent is deceased

· Parent is incompetent

· Only one parent has legal responsibility for care and custody

· Parent is not reasonably available*; explain:

*Note: “Not reasonably available” means the other parent cannot to be contacted by phone,mail,email,or fax,or his or her whereabouts are unknown. It does not mean that the other parent is at work or home,or that he or she lives in another city, state,or country.

Date of Signature (mm/dd/yy): ______________________________________

Appendix B

Full Survey Taken by Participants

Survey: Fear of Failure and Its Impacts

1) How old are you?

13

14

15

16

17

18

2) Have you ever had expectations placed on you? (by peers, friends, family, community, society, etc.)

Yes

Maybe

No

3) Who’s placed expectations on you?

Parents

Friends

Siblings

Relatives

Community Members

Peers

Teacher

Other: ___________

4) What kind of expectations do they place on you?

Gender stereotypes (such as girls have to be pretty and boys have to be strong)

Good grades

Going to college

Doing well in school

Having manners

Doing chores

Being pretty

Popular

Being likable

5) What other significant expectations have been placed on you?

6) How much have these expectations affected you?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

(Not at all) (A lot)

7) How much would you say these expectations restrict you?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

(Not at all) (A lot)

8) Are the people around you supportive? Do they respect your dreams and ambitions and help you strive for them?

Yes

Maybe

No

9) Who’s supported you?

Parents

Friends

Siblings

Relatives

Community Members

Peers

Teacher

Other: _____

10) How supportive would you say they are?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

(Not at all) (A lot)

11) Have you ever had a fear of not living up to those expectations?

Yes

Maybe

No

12) How big would you say that fear is?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

(Not at all) (A lot)

13) Has that fear affected you?

Yes

Maybe

No

14) How much has that fear affected you?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

(Not at all) (A lot)

15) Would you consider this fear as a fear of failure?

Yes

Maybe

No

16) If not, why?

17) What effects has this fear had on you?

Self-doubt

Stress

Depression

Anxiety

Loneliness

Rapid heart rate

Chest tightness

Trembling

Dizziness

Lightheadedness

Sweating

Digestive problems

Medical problems

Other: _____

18) What are the biggest effects this fear has had on you?

19) Has this fear changed the decisions you’ve made?

Yes

Maybe

No

20) How has a fear of not living up to those expectations affected the decisions you’ve made? (Please specify)

21) Have you made bad decisions from that fear?

Yes

Maybe

No

22) If so, what were they?

23) Have you made good decisions from that fear?

Yes

Maybe

No

24) If so, what were they?

Appendix C

Expectations Placed on Participants (M-S Question)

Question: What kind of expectations do they place on you?

Appendix D

Expectations Placed on Participants (Open-Ended Question)

Question: What other significant expectations have been placed on you?

Reponses:

Being responsible and “lady-like” learning how to cook etc

Being thin, being good and acting a certain way, wearing certain clothes

n/a (everything was mentioned already)

lightskinned and fair

being expected to go to medical school

Being a smart student

Not sure

Being able to grasp concepts quickly

N/A

n/a

Expectations to give more to others when the same energy is not being given to me

Setting an example

Expectations to take up opportunities in the community and serve others.

opening up more to people and reducing anxiety

Good grades

respectful

Appendix E

![]()

Figure E1. Responses when participants were asked who’s placed expectations on them (M-S question).

![]()

Figure E2. Responses when participants were asked how much expectations have restricted them (Likert-scale Question: 1-Not at all; 10-A lot).

![]()

Figure E3. Responses when participants were asked who’s supported them (M-S Question).

![]()

Figure E4. Responses when participants were asked how supportive they were (Likert-scale Question: 1-Not at all; 10-A lot).

![]()

Figure E5. Ages of participants (Answer Choices: Yes, Maybe, No).

![]()

Figure E6. Responses when participants were asked how big their fear of failure was (Likert-scale Question: 1-Not at all; 10-A lot).

![]()

Figure E7. Responses when participants were asked whether fear of failure has affected them (Answer Choices: Yes, Maybe, No).

![]()

Figure E8. Responses when participants were asked how much fear of failure has affected them (Likert-scale Question: 1-Not at all; 10-A lot).

Appendix F

Effects of Fear of Failure (Open-Ended Question)

Question: What are the biggest effects a fear of failure has had on you?

Reponses:

Sometimes I feel scared for my future and if it will work out

Loneliness and anxiety are the major things

Not being happy

It led to feelings of self-doubt and less confidence + more sadness at times

By making me think I am not good enough.

Not being able to participate in activities i like because it doesn’t uphold our “standard”

Self-doubt

stress/anxiety is the biggest affect

skin problems

Just some stress senior year. It’s mostly the stress of the year on top of the expectations.

The doubting of my abilities

No effect

constantly thinking if I’m worthy enough of my own dream and not someone else’s (my parents)

Stress

Anxiety and doubting myself a lot

Crippling mental illnesses

constantly being yelled at

anxiety

Extreme stress during tests

It’s a healthy fear that keeps me in check.

a bit of anxiety

This fear makes me feel like pursuing dreams that I am truly interested in or putting myself first in life is considered selfish. Therefore, I often prioritize others or do things that don’t give me personal happiness as a result of this fear.

Pressure

Being in a very heightened state of anxiety.

I tend to stress more and it affects my mood. I usually end up trying my best to reverse those fears.

Negative affect on self identity and confidence

Appendix G

Effect of Fear of Failure on Decision-Making (Answer Choices: Yes, Maybe, No)

Question: Has this fear changed the decisions you’ve made?

![]()

Appendix H

Effects of Fear of Failure on Decision-Making (Open-Ended Question)

Question: How has a fear of not living up to expectations affected the decisions you’ve made? (Please specify)

Responses:

I make all my decisions very carefully so as not to derail my future when I ideally would like to be doing something else that would be more fulfilling to me.

I also have to triple check my actions in case I would be disrespected someone or not maintaining the image they see me as

Every single decision has to go through like 5 different filters to see what each group of ppl like friends and family would Say about it.

I may or may not choose to participate in something

Trying to study more

The fear has caused me to shelter myself at times and pushed me to copy the actions of my peers.

I had to say no to certain activities because my parents wouldn’t approve

I’ve made choices to do extreme things that were not healthy for me to stay thin or study for tests.

actually I haven’t tried harder to meet their expectations because doing so causes more stress but it’s still in the back of my mind and causes anxiety

made me rely on other ways to comfort myself, wear clothing and act like someone thats not what my personality is really like

It allowed my to actually achieve success because it helped me realize the importance of my actions

I have taken many courses in high school to compensate for the future ahead but looking back I would have liked to do things I enjoyed more, things that interest me.

A fear of not getting good grades have affected my decision by making me make more immediate decisions.

Changing my career path.

Crippling anxiety

I would choose not to hang out with my friends in order to study so i can meet expectations

I am somewhat fearful of going outside of my comfort zone

Having a fear of failure academically causes me to sometimes believe that I do not deserve to hang out with friends even if I am ahead on work because I could be using that time to be productive in my studies.

When you lie, you automatically let down those expectations, so its a factor that forces me to stay honest.

It motivates me to live up to those expectations.

I have made several decisions to take classes that I do not enjoy or pursue steps ahead in dreams that are not mine.

I often decide how I spend my time on the weekends around my homework.

Yes, I was not very confident and often failed in the tasks I was to carry out.

Partially, I usually don’t think about probable solutions of expectations unless it’s life stimulating.

Motivate me to work harder

Hard to explane

Appendix I

Negative Effects of Fear of Failure on Decision-Making (Open-Ended Question)

Question: What bad decisions have you made from a fear of failure?

Responses:

Hurting myself

I went behind my parents back and did things they didn’t approve of

the fear of not getting good grades or SAT score should make me study more, but the expectation is so high that I feel like I can’t reach it so I give up and procrastinate studying and stuff, which is a bad decision

being someone im not

This fear is not forceful, its more like if you don’t do it, you won’t be successful. So I want to do it, it’s not necessarily a fear.

Not studying enough.

Rejected and not tried things I love.

I can’t tell you because they’re illegal <3

I may not attempt given opportunities that may have helped me out of fear.

I usually perform worse when doing a task if someone is looking over my shoulder for example

I made a decision to remain in orchestra because I was expected to show commitment. I made a decision to take classes that I truly do not enjoy because I was expected to go into the medical field.

Being irrational, spontaneous, lashing out on others. v

Give up when things get too hard

Appendix J

Positive Effects of Fear of Failure on Decision-Making (Open-Ended Question)

Question: What good decisions have you made from a fear of failure?

Responses:

I don’t do drugs and engage in other self destructive behavior so my future stays secure.

I achieved a lot of good things like winning DECA and stuff b but if I fail in anything it seems like everyone judges me immediately and it makes me feel worthless so I always try harder

Studying for a long period of time before a test instead of last minute

By pushing myself harder to achieve better grades and higher positions.

I applied for programs that my parents approved of

study and work harder to meet those expectations

Again this helps me take more rational decisons.

For example, I have taken harder classes, I have pushed myself to learn more. Secondly I have participated in extracurriculars that interest me, so that I know what I would like to do in the future. Therefore this “fear” furthers me in life.

studying

Focusing more on my tasks and deadlines I have to meet.

I prioritized my school work

Prioritizing my studies, being productive, studying more often, etc.

idk

It motivates me to accomplish certain things, as I’m a relatively unambitious person

I have also made decisions to stop procrastinating and focus on schoolwork, which has allowed me to experience hard work and perseverance.

Studying, making good grades

I have worked hard and got my tasks done quick.

I took risks and ultimate received great relationships and trust.

Work harder when things get difficult