*We have decided to put in the title: “The Fox and the Stork”, attending to the frequency of their use. In the tale of Andalousie it appears “hopona”, which means fox. We have decided also to put in the title stork because it appears in the fables of Fedro, La Fontaine and Samaniego and in the tales of Burgos and Italia, in total on five occasions; while crane appears in the Esopo fable and in the tale of Russia, raven in that of Murcia and jackdaw in that of Andalousie.

1. Introduction

We consider and believe that it is convenient to carry out the study mentioned in this article because it makes clear that there are existencial and behavioural subjects that worry the human beings from the beginning. One of these subjects is the abuse and prepotence which the strong one exerts on the weak one, which is manifested with different intensity degrees and with different causes and reasons. The fact that authors like the fable writers Esopo, Fedro, La Fontaine and Samaniego have addressed this subject, and that the same subject is addressed in folkloric tales of Spain, Italy and Russia, which are the environments addressed in this article, justify and give support to this assertion.

The “Fox” and the “Stork” give examples of human behaviours and show how the stronger and more cunning one can offend the one that is considered weaker. The subject has been chosen, furthermore, because of the reasons what have been exposed in the previous paragraph: because a transcendent fact is presented, i.e. that the weak one is not able to tolerate the offence and decides to have revenge on the strong one, as is stressed in the different phases of this study.

Starting with the attentive and critical lecture of the texts that form the corpus of this article we can affirm that, even though very extended geographical zones are being handled, which have very different cultural and linguistic characteristics, the behaviour of the players, the studied subject, the plot, the development and the conclusions are identical. The objective of this study is to verify that this assertion is effectively accomplished. The novel contribution of this article consists in handling at the same time two narrative forms, the fable and the folkloric tale, and verifying that the elements are the same.

When the “Fox” and the “Stork” are handled as a fable, it always gives a moral that appears at the end. Although it is not usual, the tale that we present, which belongs to the Andalousian ambient, also ends with a moral conclusion.

The authors of the fables that we use as sources: Esopo, Fedro, La Fontaine and Samaniego express the moral like this:

Esopo: “According to the treatment we will give, so will be the treatment that we will receive.”

Fedro: “No one must be damaged, but if anyone would do it a deserved punishment will be suffered.”

La Fontaine: “Mister fox had to return fasting to its home, with ears down, with the tail down and ashamed, as if, with all its cunning, it had been deceived by a hen.”

Samaniego: “There is also a deceit for the mischievous.”

And from our side we could say: “Tit for tat is fair play”, phraseological unit that refers to the same meaning as the morals given by the fabulists, which is of frequent use and which appears in the andalousian tale which belongs to this corpus.

In the four fables and the five tales that we analyse a conflicting situation appears, which has as origin the mocking and offence that the “Fox”, an animal characterized by its malign cunning, makes to the “Stork” in order to enjoy itself.

In all cases, from the acting point of view, the “Fox”, which appears to be the helping one, actually behaves as opponent.

The “Fox” invites the “Stork” to have a meal. The problem is that the “Fox”, both in the fables and in the tales that we study, gives food quite inappropriate to a recipient that has inappropriate characteristics for the physical characteristics of the “Stork”, which prevents the “Stork” to take it, even when trying it many times, so that the difficulties suffered give to the “Fox” a lot of enjoyment.

When the “Stork” decides to revenge, it invites the “Fox” to have a meal, and will serve the meal to a recipient that will not allow the “Fox” to take it. The “Stork” would appear to be the helping one, but in fact it acts as opponent, the reason being for revenge from the mocking and offence suffered.

The fables and tales that we analyze, according to the classification of Aarne-Thompson, belong to the type 60: “The fox and the crane invite themselves. The crane (heron) has the food in a deep dish, the fox has the food in a flat dish. The crane hurts its beak (Aarne-Thompson, 1995: p. 15).”

As we will see in the Semiotic Study, from the symbolic point of view, all authors agree in characterizing the fox as symbol of the cunning, but always a malign cunning. It knows how to offend the stork and, in all cases, it achieves its aim. However the stork represents the filial pity, the good luck, the meditation and the contemplation.

The starting point, the development and the conclusions are identical in the four fables and the five tales that we analyse. The relationship between the fables and the tales is evident.

In our case, the subject of the fox and the stork has its origin in Esopo, it would be taken by Fedro and subsequently by La Fontaine and afterwards by Samaniego.

It is frequent that certain fables are folklorised and spread in a traditional way. Many animal tales seem to come from literary esopic sources as it happens in our case. It should be distinguished, however, between fables and animal tales. The moral purpose is the fundamental characteristic which distinguishes the fable from the animal tales. Other distinctive traits are: the antiquity, the continuity and the orality.

As Rodríguez Adrados signals: “Few literary classes, if ever someone exists, present a higher continuity along the history as the fable (Rodríguez Adrados, 1979: p. 11).” And later he says:

The fable was presumably told with words improvised by the table companion, even though (s)he sticks to usual forms as when we narrate a tale. (…) The basis for the diffusion of the fable is oral. (…) Esopo gives birth to the true fable, at least in the aspect of a short narration in which, from the fact affecting some animals, a lesson or story is drawn which is useful for the human life (Rodríguez Adrados, 1979: p. 392).

García Gual says:

In the structure of the simple esopic fable several indispensable elements can be distinguished: 1) A basic situation, in which a certain conflict is exposed between two figures which are generally animals; 2) The actuation of the characters, which results from a free decision of them; 3) The evaluation of the chosen behaviour as it is reflected in the pragmatic result of the action, which is then considered as clever or stupid (García Gual, 2016: p. 30).

All these elements are found in the fables that we study.

Among the characteristics of the fable class we can mention the brevity and, in some occasions, to be in verse.

Emilio Pascual, editor and author of the Appendix and the notes of the edition of the Samaniego Fables (see the References), in the Appendix, page 280, says “The fable as class entered in Spain in the XVIII century, the century of the Illustration, the century in which the literature appreciated above all things the utility, the didactics, the educative capacity.”

In general there is an evident relationship between the fable and the animal tales. Many animal tales have a thematic which is identical to that which appears in the corresponding fable, as we can observe in our case.

But as García Gual says: “In the historical practice there may be interferences and contaminations between the tales and the fables, but in the theory it is easy to draw a general distinction between one and another class, which are diverse in their origin and intention” (García Gual, 2016: p. 22).

In the opinion of Anderson Imbert: “The tale would be a short narration in prose which, as much as it may be based on a real situation, reveals always the imagination of an individual teller (Anderson Imbert, 1972: p. 40).”

The popular tales have very old roots grounded to folklore, to customs and to religion. Through the researches of the ethnologists we know that the tale is subsequent to the legend, and they are considered as narrative inventions for the amusement of human beings. Normally the tales are not to be believed and generally they are not localized nor situated in space nor time.

Menéndez Pidal (Menéndez Pidal & Rico, 2002: p. X) in the introduction says:

The tale of popular tradition is born and lives as an essentially oral species. (…) it passes without any obstacle from one mouth to another. (…) Because of this the tale is the by excellence most emigrant literary species. It is infiltrated through the most strange linguistic territories, through the most unequal cultural spheres (Menéndez Pidal & Rico, 2002: p. X).

Thompson arrives to the following conclusion: “An even most tangible evidence of the ubiquity and the antiquity of the folkloric tale is the high similitude in the content of the narratives among the most different peoples (Thompson, 1972: p. 40).”

We have decided to study the subject of the “Fox” and the “Stork” as a fable in Esopo, in Fedro, in La Fontaine and in Samaniego, and as folkloric tale in three zones of Spain (Burgos, Murcia and Andalousia), in Italy and in Russia.

Fables.

We insert in the following the texts of the Fables and the Folkloric Tales that are being studied

ESOPO 364—The fox and the crane.

A fox invited a crane for dinner and did not supply nothing special for his invited one except a vegetable soup, which was served in a very flat and large stone dish. Because of the amplitude of the dish and the length of its neck the crane could not take the soup every time that it tried, and its anguish for the inability of eating gave the fox a lot of fun.

The crane, when it had its opportunity, invited the fox for dinner, and set before it a jug with a long and narrow opening, so that the crane could insert easily its neck and enjoy at will its content. The fox, however, was not able even to taste it, finding thus an appropriate compensation for the kind of its own hospitality.

According to the treatment we will give, so will be the treatment that we will receive.

(Fábulas de Esopo, 2010) Format and edition by J. Renato Rodríguez Rudín. Costa Rica: Ed. Educación y Desarrollo Contemporáneo S.A. San José.

FEDRO—The fox and the stork.

A fox invited first a stork for dinner and put only broth in the dish, which the hungry stork could not taste in any way. After a few days, the stork asked the fox to have lunch, and then presented it a long flask full of minced meat, in which the fox could not insert its head. But the stork, introducing its beak, could consume the meat satisfactorily, leaving its invited one quite hungry; and mocking the fox it said: “Each one must suffer resignedly the consequences of its own examples.”

No one must be damaged, but if anyone would do it a deserved punishment will be suffered.

(Méndez, Sánchez, & Inglada, 1978) La fábula a través del tiempo.De Esopo a Andrés Bello. Barcelona: Editorial Ramón Sopena, S.A.

LA FONTAINE (First Book XVIII) The Fox and the Stork.

Míster Fox decided to make a great day, and invited for lunch the Stork companion.

All the foods reduced to a very thin soup; the host was very frugal. The thin soup was served in a very flat dish. The Stork could not eat anything with its long beak, and mister Fox could sip and lick perfectly all the bowl.

To have a revenge of this mocking, the Stork made an invitation to the Fox shortly after. “With pleasure!” answered the Fox; “with good friends I do not make ceremonies”. At the agreed time the Fox went to the house of the Stork; it made a thousand reverencies, and found the food well prepared. The Fox was hungry, and the meal seemed glorious, which was a samalgundi of exquisite fragrance. But, how was it served? In a flask with a long neck and narrow opening. The beak of the Stork entered very good in it, but not the muzzle of mister Fox. Who had to return fasting to its home, with ears down, with the tail down and ashamed, as if, with all its cunning, it had been deceived by a hen.

(Fábulas de La Fontaine, 1984) Madrid: El Museo Universal (literal reproduction of that of Montaner y Simón, Barcelona, 1885).

SAMANIEGO—The fox and the stork. (First Book. Fable X)

The Fox insists

in giving a meal to the Stork;

the invitation had such expressions,

that announced doubtless provisions

of the most excellent and exquisite.

The Stork accepts joyful, goes with appetite;

but only found in the table

clear broth in a flat platter.

Useless the meal it struck with the beak,

since it was, for the meal it saw,

a useless fork its long beak.

The Fox with the tongue and the muzzle

cleaned so well its platter, that could well

serve as dishwasher if it travelled to Holland.

But shortly time after, being invited

by the Stork, found quite ready

a long flask full of minced meat;

there came its affliction and its pain;

the wishful muzzle quickly shows

to the neck of the long phial,

but in vain, as it was so narrow

as if by the Stork it were made.

By envy of seeing that at its will

with the beak sucked the Stork in its presence,

returns, tries, reflects,

sniffs, is confused, finally gets bored;

went out with the tail among the legs, so ashamed

that not even had the exit

of saying “They are green”, as long ago.

There is also a deceit for the mischievous.

Emilio Pascual says, it its footnote 2: “Merry adjective: the long flask was paunchy and full.”

(Pascual, 1982) Félix María Samaniego,Fábulas. Madrid: Edicions Generales Anaya.

Tales:

The Fox and the Stork invite each other. (p. 93) (Tordomar) (Burgos, Spain)

The stork was fishing, and said to the fox that it would give it a fish, and then the fox said to the stork that it would give the stork something that could be pleasant for the stork. And said that yes, that they would get invited for the day of each saint. And the day of the saint happened first for the fox, and the fox set a dish in which the fox could eat the chops quickly. And said to the stork: Eat, eat!

And the stork, with its beak, went and picked in the sauce. And what could it eat? Nothing! The stork could eat nothing. And afterwards came the saint of the stork, and the stork said that the fox was invited. And it had good and fine fishes, but set it in a demijohn with narrow opening, and the stork inserted its beak and extracted the fishes and ate them, and to the fox it said:

- How are they?

And said:

- Good, good!

The same as what the fox had made to the stork, the stork made to the fox.

(Marcos, Pedrosa, & Palacios, 2002). Cuentos burgaleses de tradición oral Burgos: Gráficas Aldecoa, Sdad. Coop.

The Fox and the Raven (page 299) (Sangonera La Seca, Murcia, Spain).

Once upon a time there were a fox and a raven who were companions. The fox invited the raven for lunch and said to itself:

- How funny I will be! I will make groats and put them in a slab, in this way my companion will not be able to eat it and I with my tongue will be able to eat everything.

When the raven arrived the fox said:

- Well, the banquet is ready, let’s start eating.

The raven could not eat anything with its peak and the fox was laughing internally.

- How did you fare, companion! Did you eat well?

- Yes, very well, said the raven, now it’s my turn to invite you to my home to have lunch some other day.

Then the raven thought:

- Now it’s my time to enjoy myself. I will make crumbs and will put them in a long cruet, in this way my companion, with its tongue, will not be able to eat while I, with my long beak, will eat all of them.

When the fox arrived, the raven said:

- Well, the banquet is ready, let’s go for lunch.

The raven, with its long beak, could eat in the cruet, while the fox, since it could not enter its tongue, could only lick all around.

The companion raven asked:

- Are the crumbs nice?

And the fox said:

- Yes, they were very nice, but I could not taste them. Still, the banquet is excellent.

(Carreño Carrasco, 1993) Cuentos Murcianos de tradición oral. Murcia: Universidad, Secretariado y Publicaciones.

The “Hopona” (=Fox) and the Jackdaw (p. 118) (Andalousian unpublished version facilitated by J.A. del Río and M. Pérez Bautista)

There was a fox (always a rascal) and a jackdaw. Then they became good friends. And then the fox said to the jackdaw to come, as they were to make a christening; and the fox made an invitation to the jackdaw. And then the lunch was served in one of these flat dishes…so that the jackdaw could only be there… the fox always eating with its tongue, and the jackdaw made like this with its beak and tried to sip, but did not gain anything. And the fox said:

- What! Did you get satisfied?

And the jackdaw said:

- I remained…so satisfied, that I am up to burst! For next Sunday, now, I invite you.

And the Sunday it invited the fox. And then the lunch was served in a bottle, so that the jackdaw inserted it beak and was satiated, but the fox could only look at the jackdaw. And then the jackdaw said:

- What! As you see, tit for tat is fair play.

(Camarena Laucirica & Chevalier, 1997) Catálogo tipológico del cuento Folclórico español. Madrid: Gredos.

The Fox and the Stork (p. 108-109) (Italy)

Once upon a time…there was a fox that made a friendship with a stork and thought that it would be good to invite it for lunch. In the moment of deciding what could it serve to the invited one, had the idea of making a joke. It prepared an exquisite soup which was served in two flat dishes. When it received its friend, it said:

- Accommodate yourself, my friend! In your honour I have prepared something that will please you. Frog soup with ground persil. Very rich, as you will see!

- Thank you, thank you! The stork answered as it sniffed the delicious scent. But suddenly, it realised that it had been deceived. In spite of all of its efforts, its long peak did not succeed in taking that soup from the dish, while the fox said:

- Drink! Drink! Does it satisfies you?

The stork decided to be patient and had no other remedy than following the joke.

- I have such a headache that I lost suddenly the appetite! Said with feigned indifference.

- Oh! I regret this much! A so nice soup! A pity, maybe next time! The fox answered.

It was then when the stork carried out its stratagem.

- I agree, my dear friend! But next time you will be my invited one!

The following day, the fox found in front of its door a note written very courteously in which its friend stork invited the fox for lunch.

- How graceful! Thought the fox. Not even seems to have been offended by having made a joke on it. It is really a nice friend!

The house of the stork was not as tidy as that of the fox, but the house master made soon its excuses.

- As you see, my house is not as tidy as yours, but in compensation I have prepared a special food based on craw-fish in white wine with juniper grains.

The fox, presuming in advance the taste of such exquisiteness, approached its muzzle to the jar that presented its stork friend. But, in spite of its intents, it could not reach the food that was at the bottom of the recipient, because its muffle could not pass through the narrow opening of the jar. However, the stork could eat it at will thanks to its narrow peak.

- Taste it! Taste it! Does it please you?—shouted the owner of the house without stopping devouring. The poor fox, mocked and confounded, had not enough courage to invent an excuse which justified its involuntary fasting. That night made turns and more turns in its bed without being able to seep, thinking on that succulent food that it could not swallow. Resigned, it repeated always:

- It could be expected!

(Sirena, 1991) El gran libro de los cuentos. Barcelona: Molino.

The Fox and the Crane (p. 47, volume 1)

A fox had made friendship with a crane. The were even midwifes, since in one occasion they had behaved as accoucheurs.

Then, one day the fox crossed its mind and invited the crane to eat. It went to see the crane and said:

- Dear midwife, come to eat with me, I beg you. You will see how I regale you!

The crane accepted the invitation, and the fox served in a flat dish a milk soup that it had prepared. The dish was then put over the table, saying:

- Here you have, midwife. Eat as much as you wish. I made it myself.

The crane tried to eat something with its beak, but of course! It could not get a single drop. The fox, meanwhile, was sucking the soup with its tongue until eating everything. When it finished, said:

- You will have to pardon me, dear midwife, but this is all what I can offer you.

- Thanks anyway, midwife. Now I will invite you.

The following day the fox went to the house of the crane. It had prepared okroshka (a typical summer dish, which indispensable ingredient is kvas (=refreshing beverage having few degrees made by fermenting bread of rye together with yeast and sugar), and served it in a jar with a very narrow neck, saying:

- Eat, my midwife, eat, because this is all what I can offer you.

The fox began to go around the jar, sniffing it and licking it in one side and the opposite one. But no way; it could taste no drop: its head could not go through the neck of the jar.

Meanwhile, the crane could eat everything, because with its beak it could arrive to the bottom. Then the crane said:

- Excuse me, midwife, but I cannot offer you anything more.

The fox, who had thought to have eaten for a full week, went away very disappointed and returned home exactly as it had went to crane’s house. The crane had paid the fox with the same coin. From that moment on, the fox and the crane have ceased to be friends.

Afanásiev (1985) Cuentos Populares Rusos. Madrid: Ediciones Generales Anaya (second edition) (Annotated by Afanasiev in the Kalinin region)

2. Semiotic Study

We follow the method proposed by José Romera Castillo (Romera Castillo, 1978: pp. 113-152) since from the semiotic point of view it seems us vey complete and well organised. This semiotic method created by Romera Castillo, founder of the Asociación Española de Semiótica (=Spanish Semiotic Association) and with recognized international prestige, has as starting point of view the examination of a concrete narrative in order to carry out a definitive synthesis. In this way we take into account the sequences and the types of sequences, as well as the chaining of the sequences. This allows us to establish the narrative units. The following step is to precise the function classes and finally the actions. All these analysis levels we have followed in the corpus which constitutes the basis of this article and which allow deepening better in the study of the chosen corpus. In addition we have carried out the biologic study as well as the uses and customs and the symbolic study of the animals that appear in the fables and the folkloric tales, because they provide relevant data to know and understand their behaviour.

We complement this study carrying our the scheme proposed by Bal (see the References) which allows us building the behavioural image of the subjects and establishing which is the Minimal Action or summary of all the studied texts, according with the scheme proposed by Prince (see the References) that allows expressing the contents of the studied texts in a synthesized form.

Carrying out the Semiotic Study

1) Quantification and establishment of the acting characters.

The acting characters of the four fables and the five tales are:

- the “Fox”—opponent.

- the “Stork” (crane, raven, jackdaw)—hero.

- recipients with narrow opening—helpers of the “Stork” and opponents of the “Fox”.

- flat recipients—helpers of the “Fox” and opponents of the “Stork”.

The acting secondary elements are:

- flat and ample dish—opponent.

- vegetable soup, very thin soup—opponent.

- broth, clear broth—opponent.

- chops—opponent.

- groats—opponent.

- frog soup, milk soup—opponent.

- jug—helper.

- minced meat—helper.

- samalgundi—helper.

- fishes—helper.

- crumbs—helper.

- craw-fish served in a jar—helper.

- refreshing beverage served in a jug—helper.

The “Fox”, as it was already said in the Introduction, appears to be a helper to the “Stork” by inviting it to eat, but is actually an opponent as it serves an inappropriate food in an inappropriate recipient, with the aim of mocking the “Stork” as the “Stork” cannot take it.

From the formal point of view, all the texts that make the corpus of this study include two sequencies with chaining by continuity:

Establishment of the Sequencies:

S1: The “Fox” invites the “Stork” and laughs at it.

S2: The “Stork” invites the “Fox” and laughs at it.

Classification of the functions:

As distributional functions we have:

1) cardinal functions or nuclei:

- invitation—mocking.

- invitation—reveng.

2) secondary functions or catalysis:

- the specific recipients used by the “Fox” and the “Stork”.

- the specific types of food used by the “Fox” and the “Stork”.

All these elements can be substituted by others which may carry out the same actions; they are necessary, but not essential, they can be replaced.

3) integrating functions:

- 1.—indexes:

- inviting the “Fox” to the “Stork” (cunning).

- putting inadequate types of food in inadequate recipients (wickedness).

- 1. –informations: (space and time).

- the “Fox” invites the “Stork” to its house (space) for a meal (time).

- a short time later the “Stork” invites the “Fox” to his house (space) for a meal (time).

Quantification of the acting elements:

S = “Stork”.

F = “Fox”.

Al. – Rec. (S) foods and recipients used by the “Stork”.

Al. – Rec. (F) foods and recipients used by the “Fox”.

Indication of the acting elements that intervene in each of the sequencies:

S1: F, S, Al.—Rec. (F)

S2: S, F, Al.—Rec. (S)

Concerning the establishment of the acting elements we have:

- The “Stork”, besides being hero as we have said, is subject of ingenuity, object of mocking by the “Fox” and addressee of the insult and offence caused by the “Fox”.

- The “Fox”, besides being opponent as we have said, is subject of cunning and wicknedness, object of vengeance by the “Stork” and addressee of the vengeance by the “Stork”.

- The foods and recipients used by the “Stork” are addressees of the gratefulness by the “Stork”.

In the quantification of the events we have:

A1 = the “Fox” invites the “Stork” to have a meal in its house.

A2 = the “Stork” goes to the meal.

A3 = the “Fox” serves inadequate food in inadequate recipients.

A4 = the “Fox” laughs by seeing the difficulties of the “Stork”.

A5 = the “Stork” invites the “Fox” to have a meal in its house.

A6 = the “Fox” goes to the meal.

A7 = the “Stork” serves inadequate food in inadequate recipients.

A8 = the “Stork” succeeds in having a revenge of the “Fox”.

Resolution of the events (actions)in which each of the actors participate:

F = A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8

S = A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8

As basic predicates we see that:

- The “Fox” knows, wants and is able to mock the “Stork”.

- The “Stork” does not know that the “Fox” wants to mock the “Stork”, and when it knows it, wants to revenge and is able to do it.

3. Biological Study

The biological characterization of all the animals that we show in the following and which appear in the fables and the folkloric tales studied here have been taken from the (Gran Diccionario Enciclopédico Ilustrado de Selecciones del Reader’s Digest, 1972) (see the References). Knowing these characteristics helps to understand better the position described in the fables and in the folkloric tales studied.

Biologically the fox belongs to the canids family, class of carnivorous. It is a mammalian of some 60 cm. in length from the muffle to the beginning of the tail, which has a 30 cm. in length. It has a broad head, a pointy muffle, steep-high ears, the body covered with dark abundant hair and a broad tail. It attacks the fowl corrals and chases all kinds of hunting. These characteristics apply also to the fox that appears in the fable of La Fontaine.

In the title of the Andalousian tale appears the termhopona, that is the usual way to name the fox in Andalousia. It is a derivation of hopo which means very hairy tail, as those which have the fox and the sheep.

Biologically the stork is a long-legged bird of the ciconid family, class of ciconiform. It has large size, long and bulky beak, long and sometimes naked neck, thin and robust feet, with short fingers, with and black and white or grey (or just black) feathers, is carnivorous and migratory. It appears in the fables of Fedro, La Fontaine and Samaniego and in the tales of Burgos and Italy.

The crane appears instead of the stork in the fable of Esopo and in the tail of Russia collected by Afanasiev; it is long-legged and gruiphorm; it is similar to the heron, but flies with an extended neck and not in form of an S as does the latter.

The raven is passeriform, of the corvid family; it is carnivorous, with black feathers (sometimes with bluish colour) and has conic beak longer than the head, strong ankles, wings having up to one meter length and tail with rounded contour. It appears in the tale of Murcia.

The jackdaw is also passeriform and of the corvid family. A bird which is very similar to the raven, with a violet-blackish colour, with red beak and the feet and long and black claws. It appears in the tale of Andalousia.

Usages and habits.

Each one of these animals behaves according to their usages and habits; so it is important to know and have always present these traits as they help understanding the studied texts.

The fox (canis vulpes), according to Claudio Eliano “reaches insuperable levels of malignity and rascality, is a knavish animal and, because of this, the poets usually call it cunning (Eliano, 1984: p. 39).”

In El Fisiólogo we find:

The fox is a crafty animal. When it is hungry and lacks any food, goes to a sunny place; lying on the floor and retaining its breath feigns to be dead, and lies on its back with the eyes open and the legs high. The birds go down to eat the fox, but it seizes them by surprise and devours them with pleasure.

And afterwards the following comment appears: “The fox is par excellence a crafty animal, and is able to fish fishes at the border of the rivers, and can attack hedgehogs by returning them upside down (El Fisiólogo, 1986: p. 112).”

In the Bestiario toscano, in the entry “Of the fox”, we find: the fox has many names: fox, she-fox and others, and /is a very cunning and false beast/ (El Fisiólogo, 1986: p. 130).

Of the stork (ciconia alba) Claudio Eliano says:

The storks chase with much cunning the bats that intend to spoil the eggs, as just a mere touch by the bats makes them barren. This is the way that the storks use against this: they bring banana leaves to the nests and when a bat approaches them, they become paralyzed and are unable to make any harm (Eliano, 1984: p. 37).

He says then:

The storks take care with loving solicitude to their parents when they are old. It is not a human law what exhorts these birds to do so, rather the reason for such behaviour is their own Nature. These birds also love their descent (Eliano, 1984: p. 23).

Another typical behaviour is: “When they are wounded, they crush wild marjoram so that afterwards, placing it on the wounds, they heal the body and have no need absolutely of the medical art of humans (Eliano, 1984: p. 46).”

In El Fisiólogo we find:

The stork is an ash-coloured bird, the life of which is ruled by migration, so that they come in spring and go in winter to warmer lands; but when they return they recognize their nests like humans do with their houses. Their singing is a rattling which is made when its companion arrives, expressing thus its joy, when it wants to protect itself or when it wants to manifest some fears. It is an essentially beneficial animal as it cleans the fields from snakes. The pity and the mercifulness are the dominant virtues in the symbolism of the stork (El Fisiólogo, 1986: p. 46).

In El Bestiario toscano we see:

The stork is a great bird, and has shown the humans many things with its gifts. And has this characteristic: that during the time in which the mother works to feed their sons, also their sons feed and nourish their mother, and still they offer their mothers more: that when they know that it is too old, they work in order to be able to (maintain, attend and) rejuvenate, and they cut the wings with their beaks so that it may renew them. This evidences how the sons care their mother (El Fisiólogo, 1986: p. 40).

For the raven (corvus corax) Claudio Eliano says:

It is said that the raven is a sacred bird and servant of Apollon. For this reason people say that this is a bird appropriate for prophecy, and those who understand the bird attitudes, their shrieks and their flight, either to the left or to the right, can foretell according to the way of croaking. (…) If the raven croaks with garrulity, agitating the wings loudly, it is the first to realise that there will be a storm (Eliano, 1984: p. 48).

In El Bestiario toscano in The Raven, we have:

The raven is a fully black bird, and has this characteristic: that when their kinds are born, they are all white, and when the raven sees that they are not of the same colour, it abandons them and feeds them no more until they become again black; then God feeds them, and nurtures them with the dew of the sky (and of the wind) (El Fisiólogo, 1986: p. 20).

For the crane (grus cinereus) in Claudio Eliano we find:

The croaking of the crane produces violent showers. (…) The cranes are born in Tracia, the most windy and cool of the territories. (…) I know, because Aristote says it, that the cranes come flying from the sea to the land and forecast to the clever persons the menace of a violent storm. If their flight is calm, they forecast good weather and quiet wind, and if they fly silent, they remember with their silence, to those expert in these indispositions, that there will be gentle weather. And if

giving croaks and the flock of birds is smashed because they are agitated, then they foretell a strong storm

(Eliano, 1984: p. 44).

In El Bestiario toscano we have:

The crane is a bird which has a long neck; and before depositing the food in its stomach, it twists three times its neck because of its length. (…) The cranes are birds that have great and long legs (and long neck) and have a very wonderful characteristic: whenever they are all together, there is one who is always awake in the night, and the other during the day (to protect the others); that one who should be awake keeps a stone in one of its legs so that, in case the stone falls, it would return to be awake in case it would become sleepy; and in this way the others can sleep safely, and in this way each one watchs over the cave (El Fisiólogo, 1986: p. 14).

The jackdaw from the point of view of usages and habits is very similar to the rave.

4. Symbolic Study

It is convenient and opportune to take into account the symbolic aspect of all the animals that take part in the fables and in the folkloric tales because, as we have seen in the Introduction of this article, the attitude and behaviour of each one of these animals symbolize the ways and styles of being with a moralizing objective that is mainly characteristic of both the fables and the folkloric tales.

According to Cirlot: “The fox in the Middle Ages was a frequent symbol of the devil. It expresses the lower aptitudes, the tricks of the adversary (Cirlot, 2011: 476).”

In Biedermann we find: “The fox is in many popular traditions the animal symbol of the malign cunning. In general the negative symbolic meanings of the fox predominate (Biedermann, 1993: 491).”

In Chevalier-Gheerbrant we find: “The fox is taken in general as a symbol of cunning, but almost always of a harmful cunning (Chevalier-Gheerbrant, 1991: p. 1090).”

The stork in Cirlot is described like this:

This bird had been consecrated to Juno by the romans, symbolizing the filial pity. It figures also as an emblem of the traveller. In the allegory of the “Great Wisdom”, two storks in fort of each other appear flying in circles around the figure of a snake (Cirlot, 2011: p. 135).

In Biedermann we have:

Although the Bible classifies all the long-shanked birds as “impure animals”, the stork is ordinarily considered as symbol of good luck, mainly because it exterminates snakes. An old legend indicates that the stork feeds its old father, which makes it a symbol of filial love. Its resting position on a single leg causes an effect of dignity, reflection and watchfulness, which also made of the stork a prototype of the meditation and contemplation (Biedermann, 1993: p. 106).

In Chevalier-Gheerbrant we find: “Although the Levitic classifies the stork as filthy, it is almost always a bird of good omen. It is a symbol of filial love, as it is pretended that it feeds its father in its old age (Chevalier-Gheerbrant, 1991: p. 290).”

The raven in Cirlot is described like this: “In the classical cultures it loses certain mystical powers, attributing to it a special instinct to forecast the future, and because of this its croaking was used especially in divination rites. In the Christian symbolism it is an allegory of solitude (Cirlot, 2011: p. 165).”

In Biedermann we find:

In the mythology and in the symbology the raven is mainly interpreted in a negative manner, but is appreciated in some occasions by its cleverness. Plinio mentions the voice of this bird “as strangled”, being a messager of misfortune; and he says that it is the only one among all birds that seems to understand the omens (Biedermann, 1993: p. 139).

Chevalier-Gheerbrant say for the raven: “The colour of this bird, its mournful shriek, and also the fact that it is fed with dead animals make from him for us a bird of bad omen (Chevalier-Gheerbrant, 1991: p. 390).”

The crane in Cirlot is described in this way: “From China and up to the mediterranean cultures, it is an allegory of the justice, longevity and good and solicitous soul (Cirlot, 2011: p. 236)”.

Biedermann says:

In the Antiquity, it was admired because of its unwearied ability to flight, and a crane wing was considered as an amulet against tiredness. It was also a symbol of knowledge, probably because the “contemplating” effect of this animal in its resting position (Biedermann, 1993: p. 217).

Chevalier-Gheerbrant say: “The crane is, in Western countries, a common symbol of stupidity and dullness (Chevalier-Gheerbrant, 1991: p. 543).”

This opinion is contrary to what we have seen in Biedermann.

The jackdaw from the symbolic point of view coincides with the raven.

From the narrative point of view, in what is related to the time, the fables as well as the tales that form the corpus are of the type summary with the typical frequence of the iterative statement.

The narrated facts, from the aspectual point of view, belong to the method Narrator = Character (vision with): the I of the creator (narrator in this case) is confounded with the players/performers so that all people know with the same limitations the unfolding of the action, alternatively creating a fluctuant reasoning that is displacing from I to it.

In our case an implicit narrator is being handled, and each player/performer is its own information source.

In the Modality way what we see is a narrative with a discursive form which is intercalated with dialogues that give it realism and vivacity.

After the study that we have carried our until now, we know the framework which affect to the characters and we can build their images taking into account three fundamental behaviour features, as are the strength, the diligence and the flexibility (as the ability to change of attitude or opinion). For this we follow the scheme of Bal: (Bal, 1985: p. 95).

+ = positive pole; - = negative pole; Ø = not marked.

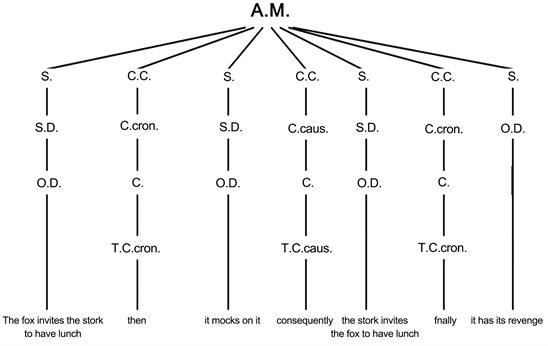

As a complement of all this study we consider very appropriate to make use of the Minimal Action scheme proposed by Prince (Prince, 1973: p. 83).

This scheme allows representing step by step both the grammatical and the narrative levels.

The Minimal Action or summary of the four fables and the five tales studied is:

“The fox invites the stork to a meal,and then it makes mockery of the stork; consequently,the stork invites the fox to a meal,and finally it has its revenge.”

Meaning of the abbreviations of the scheme:

A.M. = Minimal action.

S. = Event, happening.

C.C. = Nexus, association.

S.D. = Dynamic event.

C. cron. = Association of chronological event.

C. caus. = Association of causal event.

O.D. = Dynamic speeches.

TC. cron. = Association of event of chronological order, 1˚ causes 2˚.

TC. caus. = Association of event of causal order, 1˚ causes 2˚.

5. Conclusion

The emphasis and the referential significance of this study consist in having shown, thanks to the semiotic study carried out, how the subject, the argument, the unfolding and the conclusion are identical in the two narrative forms: the fables and the folkloric tales. After carrying out all the steps of the chosen semiotic study method and taking into account the complementary data obtained with the biological study, the usages and habits and the symbolic study of the animal characters, and having carried out the schemes of Bal and Prince, we have verified and can confirm this conclusion: that the statement that we had made both in the Abstract and in the Introduction on the coincidence in content, narrative scheme, unfolding and outcome in both narrative forms, the fables and the folkloric tales (which are included in the texts that make the corpus of this article) are fully correct, even if all these narratives, as we have said, involve a very broad zone which has very different cultural and linguistic characteristics.