Determinant of Health Care Utilization Behavior in Households in the City of Abidjan during an Episode of Illness ()

1. Introduction

According to Picheral (1984) [1], the use of health care is the expression and manifestation of individual and collective behaviors that are a function of socio-economic and socio-cultural determinants (age, gender, family and social background, income, religious affiliation, level of education, health education, etc.), medico-social determinants (reception capacity, health care facilities, etc.) and geographic determinants (urban, rural or peri-urban environment, space, and place of living, distance/time relationship with the service provider, etc.).

Studies of healthcare-seeking behavior in sub-Saharan Africa have emphasized the notion of care, therapeutic habits, and therapeutic pluralism. This research also refers to the multiple strategies implemented by the population to make the best use of the full range of available therapies (Fainzang, 1986 [2]; Willems et al., 1999 [3]; Lovell, 1995 [4]; Locoh et al., 1999, p. 17 [5]; Ryan, 1998 [6]; Goldman et al., 2000 [7]; Adjamagbo et al., 1999 [8]; Amat, 2003 [9]; Caldwell et al. [10]).

In these studies, the research framework is general and takes little account of the specificity of morbid episodes and social, cultural, economic, anthropological, and epidemiological contexts. This research identifies universal determinants of the use of health structures and sometimes traditional medicine and neglects the diversity of therapeutic practices that may exist, particularly in a large city.

They do not reflect the major role that place of residence can play in the choice of treatment.

In Côte d’Ivoire, and particularly in Abidjan, authors have also been interested in studying the use of care or the demand for care by households (M. Ymba, 2013 [11]; M. Mariko, 1999 [12] and 2003 [13]; Kouassi, 2008 [14]; Y. Kéoula, 2000 [15]; B. Touré, 1993 [16]). These studies have looked at the monetary and non-monetary aspects of the demand for health care and also at the quality of health care services. Very few studies have taken into account the social, environmental, economic, and cultural dimensions in the same study in Côte d’Ivoire and the entire city of Abidjan. These studies have also neglected certain important aspects of health care behavior, such as the different actions or steps (therapeutic itinerary) undertaken by households in the event of illness to care for the patient, the impact of the characteristics of the living environment on health care behavior, and the different health insurance systems that cover household health care expenses.

We propose to focus our study on the analysis of household health care utilization behavior in the city of Abidjan during an episode of illness. Our analysis takes into account the different social spaces of life, which is rare in studies of health care use in Côte d’Ivoire. The aim here is to highlight the specificities of the city in terms of healthcare use. It is not a question of describing and analyzing only the behavior of households’ use of health care, but of providing explanatory elements that make it possible to understand this use, as well as the different steps and actions, were undertaken by households to treat themselves and their patients: this is the therapeutic itinerary, taking into account the places of residence and the characteristics of the households themselves.

The therapeutic itinerary refers to the different routes used by individuals to obtain care (M. Harang, 2007) [17]. It is therefore the decisions that individuals make in terms of seeking care. The first stage of this therapeutic pathway is the subject’s perception of a health problem that is likely to be interpreted in terms of a disease. More simply, therapeutic itineraries can be considered as a succession of health care recourse, from the beginning to the end of the illness (Diakité et al., 1993) [18]. Several authors have emphasized therapeutic pluralism as one of the main characteristics of large cities in Africa (A. Dorier, 1995) [19]. This is why, on a smaller scale, we are interested in the place of the various resources used by city dwellers: the hospital, the pharmacy, the public health center, the private nurse, etc. The study of the therapeutic itinerary in this work focuses on the modern health care offer on the one hand, and the overall healthcare offer on the other.

Our study seeks to analyze other new determinants and focus on a more detailed study of the use of care. The study aims to analyze the determinants of health care seeking in households in Abidjan during an episode of illness.

This broader approach to disease-related behavior will make it possible to understand the basis of the care practices acquired by the populations of the city of Abidjan. On the other hand, by comparing health care utilization behaviors, we will be able to determine possible specific populations and territories of health care utilization.

2. Methodology Approach

2.1. Survey Sites

It is a survey of a sample of the population whose characteristics, opinions, attitudes, behaviors, and intentions in therapeutic practices are to be known.

To select the survey neighborhoods, we relied on the stratification of the city that was performed by demographers from the National Institute of Statistics (INS, 2014) [20]. To classify the neighborhoods, they used the environmental profile of the neighborhoods by the municipality as a stratification criterion. The typology of neighborhoods takes into account the type of habitat, the level of viability in terms of facilities, density, promiscuity in the neighborhoods, the level of urbanization, the level of social facilities, the type and construction materials of housing, the type of subdivision, the density of the built environment (dense habitat, sparse habitat), the profile of the population (standard of living, socio-economic activity, level of education, unemployment rate, etc.). The analysis identified four subsets, each of which contains neighborhoods that are homogeneous in terms of these criteria. These four strata are urban sub-spaces of the places of residence of the households: the residential neighborhoods, the evolving neighborhoods known as popular or modest, and the Ebriés villages, known as the traditional zone, which belong to the regular city and the precarious neighborhoods known as poor, which belong to the irregular city. We did not want to take into account only the central or peripheral position in the choice of neighborhoods, but the social and cultural characteristics that define them. We wanted to respect the heterogeneity of the city’s spaces, which can be a determining factor in the behavior of households.

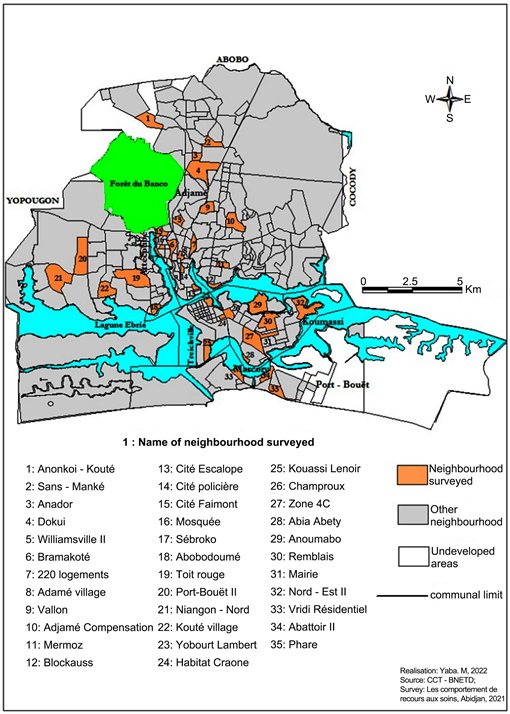

Subsequently, we drew lots in each stratum to survey the neighborhoods. This operation took into account the ten communes. In the end, we retained 35 neighborhoods corresponding to 35 different visions of the economic capital, including 10 residential neighborhoods, 10 working-class neighborhoods, 9 precarious neighborhoods, and 6 Ebriés villages, distributed in the 10 communes of the city of Abidjan (Table 1; Map 1).

2.2. Conceptual Models for Analyzing the Use of Health Care by Households in the City of Abidjan

Beginning in the 1950s, various conceptual models emerged to analyze the determinants of health care utilization and treatment pathways. In 1974, Anderson and Newman [21] presented a theoretical model that is still used today as the basis for many studies on the determinants of illness behavior. The model is based on groupings of determinants of healthcare utilization within a simple structure aimed at linking individual variables to healthcare utilization behaviors. They distinguish several categories of determinants.

![]()

Table 1. Neighborhoods selected for home surveys.

Source: Household Survey, Abidjan, 2021.

Map 1. Location of neighborhoods selected for the household surveys.

“Predisposing factors” are key demographic characteristics of the individual such as age, gender, and marital status. They reflect the propensity of each individual to use care. Social factors such as level of education, ethnicity, and occupation also measure the individual’s organization to cope with health problems (Andersen, 1995) [22].

“Enabling factors” (we will refer to them as “facilitating” or “enabling” factors) constitute the capacity of an individual to obtain care. These factors refer more to the attributes of the individual and the community in which he or she lives (level of household income, place of residence, household size, integration into urban life, membership in social networks, etc.). Enabling factors also include the distribution of care facilities, availability, quality, cost of care, travel time, possession of health insurance, etc. All of the “enabling” factors affect the individual’s ability to access the health care system.

Finally, the nature of the illness, its frequency, duration, severity, and the effectiveness of certain remedies determine the set of “needs factors” (which we will also call “needs factors”) which are the characteristics and perceptions of the individual’s state of health or illness.

These three groups of factors influence individuals’ therapeutic practices. According to Wyss (1994) [23], all of these factors exert limits on health practices and guide individuals’ choices. The actual strategies of recourse thus result from the superposition of the expected benefits and the obstacles encountered by the individual.

In 1983, Kroeger [24] [25] proposed a version of this system adapted to developing countries. He articulates his thinking between the meeting of the demand for care shaped by predisposing factors, the characteristics of the disease, and a supply of care characterized by its diversity, its quality, and its accessibility. This encounter gives rise to four main types of recourse: traditional self-medication, modern self-medication, recourse to a modern healthcare structure, and recourse to a traditional healthcare structure.

Other models have followed, in particular, those oriented toward behaviorist approaches the “health belief models” inspired by the work of Becker (1977) [26]. The hypothesis underlying the implementation of this model is that “every individual is likely to take action to prevent an illness or an unpleasant situation if he or she has a minimum knowledge of health and if he or she considers health to be an important aspect of his or her life” (Godin, 1988) [27].

We will rely on these models, particularly the one developed by Aday and Andersen (1974) [28], but we will adapt it to our study because this model is too complex and ambitious because of the numerous data required for its implementation that we do not have.

2.3. Data: Household Survey in Abidjan

The data collected in this study came from a household survey. It remains the only way to obtain information on the health status of users, of the actual use of modern medicine and non-users of health care services, and to provide data on the perceived and felt morbidity of a population, which leads to “health care research” (Develay, 1993) [29], a precept that we will analyze.

We hope to be able to identify the main factors that limit risk behaviors in populations when seeking care and the representations, knowledge, attitudes, and practices of populations in the face of disease.

The household surveys were conducted in two periods, the first at the beginning and end of the dry season in February (12 weeks) and the second at the beginning and end of the rainy season from June 15 to August 15, 2021 (8 weeks), to test the effect of the seasons on certain pathologies and therapeutic behaviors.

For the selection of the persons to be surveyed, we proceeded by quota sampling, applying the following mathematical formula

N = t2 × p (1 − p)/m2 with N: Sample size, t: 95% confidence level (standard value 1.96), p: Proportion of deaf people assumed to have the desired characteristics. This proportion varies between 0.0 and 1 and is a probability of occurrence of an event, and m: margin of error at 5% (standard value 0.05). Thus defined, the number of persons to be interviewed amounts to 758 (Table 2).

A questionnaire is used to collect qualitative and quantitative information on the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the household (age, sex, level of education and literacy, employment, etc.), the most frequent illnesses in the last two weeks, the use of general health care, and the therapeutic itineraries during a morbid episode. To collect information following a disease episode that may or may not have resulted in actions that are expected to lead to recovery, a two-week recall period is most often recommended (Kroeger, 1985 [30]; Ross and Vaughan, 1986 [31]; Timaeus et al., 1988 [27]). This recall period is short enough to limit inaccuracies and underreporting bias.

We then asked these questions in succession:

• Have you had a health problem in the last 15 days?

• What signs made you think that something was wrong?

• Following this problem, did you go to a health care facility?

• If so, what type of structure did you consult?

• If not, what have you done to treat yourself?

These questions allowed us to identify a body of knowledge about therapeutic behaviors in the specific context of an urban setting in a developing country.

To interview households, we selected concessions or blocks from the cadastral map of the neighborhoods studied. We obtained the cadastral plans of all the neighborhoods from the Bureau National d’Étude et du Développement (BNETD) in Côte d’Ivoire. The concessions were drawn at random from these cadastral plans using the GIS tool.

In the selected concessions, the household was eligible if, and only if, the head of the household was over 30 years old and had resided in Abidjan for more than 5 years. The inclusion of a minimum duration of residence in the neighborhood appeared essential if we wished to measure the influence of the characteristics of the neighborhood of residence on the health and behavior of individuals. This restriction makes it possible to exclude individuals who have recently arrived in the neighborhood and for whom it would have been incorrect to look for any influence of the neighborhood of residence on their therapeutic use. The five-year time limit seems sufficient to give adults time to integrate into their neighborhoods and adopt the urban lifestyle. Within each eligible household, adults over 30 years of age were interviewed.

![]()

Table 2. Sample of the household survey in Abidjan.

Source: Field Survey, Abidjan, 2021.

Before we began interviewing households, we had to find interviewers to help us carry out this work. Ten interviewers were trained to familiarize themselves with the questionnaire. In each commune, two interviewers were assigned to submit the questionnaire to the various households (head of household or any other person likely to answer the questions validly) selected in the neighborhoods. Our research respects all ethical considerations suggested in human and social science surveys. Indeed, our approach does not involve any risk for the participants, whose consent was obtained before any data collection activity. This being said, we discussed with the heads of the neighborhoods or villages to obtain their consent to collect health information from households in the neighborhoods concerned at the time of the activities with other investigators, who had received prior information about our visitors from them. The anonymity of the participants and the confidentiality of the data collected were assured.

2.4. Analysis Methods

To analyze disease behavior and identify determinants of health care utilization, we used conceptual models and statistical techniques. The completed questionnaires for the cross-sectional household survey were quality controlled. The data were then entered into a data entry mask developed in Epi Data and transferred to SPSS and Excel for statistical processing. The analysis strategy is based on three successive, interrelated steps that provide complementary knowledge. First, we conducted a general analysis of the most frequent diseases and therapeutic practices in the neighborhoods. Secondly, we looked at the therapeutic itineraries and the individual determinants of therapeutic practices, analyzing their influence at the univariate level.

To understand the weight of the different factors on the use of care, we will multiply the univariate and correlational analyses. These univariate analyses aim to describe the impact of multiple parameters grouped into thematic fields. To do this, we will draw on Andersen and Kroeger’s model by defining three categories of variables: predisposing factors, facilitating factors, and factors related to representations of one’s health and the characteristics of the disease (need factors). Using cross-tabulations and statistical associations, these latter analyses will help to study the role of these factors in the process of determining healthcare-seeking behavior.

We assessed the significance of the statistical relationships by subjecting the consequences assumed to be induced by them to Pearson’s chi-square test. The degree of significance of the associations was indicated by Pearson’s p-value.

Third, we conducted a spatial and contextual analysis based on neighborhood characteristics. Finally, at the end of this descriptive exploration, we built multi-variate analysis models.

After describing and characterizing the overall use of health care, it will be necessary to understand the mechanisms and determinants of this use and to examine the relative contributions of the various factors. For these reasons, we opt for logistic regression analysis. Binary logistic regression is a statistical technique for establishing a relationship between a dependent variable and explanatory variables. In the analysis of the determinants of health care use, logistic regression remains the most widely used method in the sense that the coding of data between use and non-use lends itself to this choice. We have noted many examples in the literature on this precise theme (Leyva-Flores et al., 2001 [32]; Taffa and Chepngeno, 2005 [33]).

This model distinguishes the factors that play a role in the use of care and allows us to deduce the decision processes that govern the use of care.

We want to study more precisely the influence of the context of residence on the logic of care use through this multilevel analysis. We will know whether the geographical disparities in the use of health care observed between neighborhoods are due “solely to the characteristics of individuals, which vary from one place to another, or whether the characteristics of the context of residence have their effect” (Chaix and Chauvin, 2002) [34]. This analysis will highlight the factor(s) that explain(s) the choice made by the household to care for itself or a patient.

3. Results

3.1. Description of Episodes of Reported Morbidity in Youth and Adults

During the 15 days before the survey, 32.3 of youth and 42% of adults experienced a health problem. Table 3 summarizes the main health problems reported by youth and adults during our visit. Malaria was the most common health problem for both adults (32%) and youth (29%). Digestive and respiratory problems are less important among youth (6% and 8% respectively), but slightly higher among adults (8% and 23%), and fatigue, aches, and pains are more frequent among adults (16% and 20% versus 10% and 12%). Adults also suffer more from fever than youth. The health problems identified are more important and diversified among adults. Skin problems, eye problems, coughs, cholera, and reproductive tract problems were more common among adults in the “other” category.

![]()

Table 3. Most common diseases in youth and adults.

Source: Field Survey, Abidjan, 2021.

3.2. The Different Types of Therapeutic Resources Used by Youth and Adults to Treat Themselves

Three (03) health care behaviors were identified in the therapeutic use of youth and adults. Thus, 29% of adults went to a health professional, 54% used self-medication and 17% did nothing (Table 4). While the proportion of adults who used a modern health care service was almost the same as for youth, adults used less self-medication (54% vs. 61%) and gave up seeking care more (17% vs. 11%). Among adults, it seems that ailments must be long-lasting and recurrent to be considered serious and require recourse to modern service. In many cases, before a real and official recourse, the adult will exhaust the resources that he/she has mobilized in his/her environment: advice, traditional medicines, etc. The recourse to a care structure must be justified and most often the inability to go to work will be a triggering element. Thus, as in the case of young people, the severity of morbid episodes appears to be a more important factor in encouraging adults to seek care than young people.

Modern self-medication was favored by 83% against 20% of traditional treatments. These treatments came mainly from the private pharmacy (51.8%). Like young people, few drugs were purchased directly from the generic essential drug store. On the other hand, adults more often used street medicine vendors (14.5%).

Lack of financial means was the main reason given by adults for not seeking care, followed by the lack of seriousness of the problem (28%) and its spontaneous recovery (13%). Other reasons given for not seeking care were lack of time or lack of transportation. Several adults also pointed to the knowledge of a nurse or doctor in their network of acquaintances who could provide care at home.

Finally, like young people, adults turned more to public health care facilities. However, unlike young people, adults made greater use of private facilities (22.1%) than of religious facilities (14.8%). Despite the higher cost of care, the use of private facilities is on the rise, a sign of a change in health care in the city. Adults also use the university hospital more frequently than young people (4.9% versus 1.9%). This is justified by the fact that adults only use the facilities when the illness becomes very serious, thus requiring a higher level of care than can be provided by the university hospitals.

On the whole, adults are also more mobile, they can consult at their place of work, leisure, or residence, which explains why their care practices are more diversified.

Because population behaviors differ by type of care, distances to care are not an obvious problem.

3.3. Determinants of Treatment-Seeking Behavior Studied

In this section, we analyze the determinants of health care utilization using univariate and multivariate analyses. The objective is to provide explanatory elements to the care-seeking behavior of the populations, and the use and non-use of health services.

![]()

Table 4. Distribution of ill youth and adults by primary care.

Source: Abidjan Health Survey, 2021.

3.3.1. Univariate Analysis of the Determinants of Health Care Use Behavior

1) Population characteristics as a determinant of care-seeking behavior among adults: Care-seeking behaviors about predisposing factors

In our sample, women used a modern health care service more often than men, and men used self-medication more often than women (Table 5). A large number of women’s use may be explained by their physiological condition. Indeed, women are more familiar with the health care system than men, particularly because pregnancy, gynecological visits, or family planning sessions lead them to seek medical care more often. However, they have also given up care more often than men. Women are proportionally almost 1.9 times more likely than men to do nothing in case of illness (4.4% and 2.5% respectively). This difference is just statistically significant (p < 0.049). Not seeking care decreases with age. While 27.3% of young women (15 - 19 years old) have given up any treatment, only 12.2% of those over 55 have done so. These results, therefore, show a more serious awareness of health problems, but also the appearance of more serious health problems with age. It can be said that the age of the patient plays an important role in the choice of therapeutic recourse in the face of the disease.

With strong significance, the level of equipment is related to the care-seeking behavior of adults: the higher the level of equipment in the household, the more the members of the household consulted a care service.

Among the socio-professional categories, housewives, shopkeepers, and transporters were more likely to forego care, while office workers, civil servants, and young executives were more likely to use care services. The state mutual insurance system from which civil servants benefit could have an impact on the use of health care.

Civil servants are by far the most frequent users of modern and traditional medicines together to treat themselves from the start of self-medication (15.7%, p < 0.0003), whereas the other professional categories do so very little (shopkeepers) or not at all (transporters, craftsmen). On the whole, civil servants were less inactive in the face of illness.

![]()

Table 5. Behaviors of ill adults according to selected predisposing factors.

Source: Household Survey, Abidjan, 2021 *: Not significant.

Regarding the type of housing, we find that living in a permanent building or a villa or apartment building seems to be linked to higher use of modern care.

Household position, household size, or ethnicity does not appear to affect health care utilization behavior. Finally, Muslims were more likely than Christians (21.8% vs. 15.4%) and adults with no schooling to have foregone care compared to those with primary or secondary schooling and above.

The set of variables representing the adult’s socioeconomic level largely supported the therapeutic choice.

2) Care-seeking behavior according to the characteristics of the patient and the disease: needs factors

Therapeutic action is highly significantly associated with the perceived severity of illness (p = 0.0001). The same was true for each of the three therapeutic actions taken separately (p = 0.043 for therapeutic inaction and p = 0.0001 for self-medication and external resources).

Everywhere, there is a gradation in the frequency of therapeutic behaviors, depending on the perceived severity of the disease (Table 6(a)). But the differences between very severe and fairly severe cases are minimal. They are, on the other hand, important between these two categories on the one hand and those of little or not serious illnesses on the other hand.

Therapeutic inaction decreases as the perceived severity of the disease increases (4.6% for diseases of little or no severity, versus 1.9% for very severe diseases). The same is true for self-medication (77.9% versus 63.2%).

On the other hand, the frequency of recourse to health services doubles for very serious illnesses (34.9% versus 17.5%).

A significant recourse to traditional medicine is also noted for serious cases.

The therapeutic latency period (time between the first symptoms and the start of treatment) was significantly longer before external recourse than before self-medication (p = 0.0001).

81.5% of patients initiating therapeutic action on the same day as the symptoms are noticed choose self-medication, which nevertheless constitutes only 71% of all first treatments. However, as soon as the therapeutic latency exceeds 1 day, the relative frequency of self-medication drops (68.2% for a latency of two days, 51.6% for five days, rising to 63.6% after one week).

Regardless of the length of therapeutic latency, self-medication is still more frequently chosen than external recourse.

There is therefore a tendency to resort to self-medication more quickly than to a health specialist. This is probably a consequence of the greater geographical and financial accessibility of self-medication.

Most treatments begin on the second day when the disease is well established and arrangements for treatment have been made.

The proportion of external recourse then increases sharply, then stabilizes, and even tends to decrease.

(a) ![]() (b)

(b) ![]()

Table 6. (a) Behaviors of ill adults by selected factors characteristic of perceptions of health status and reported health problem; (b) Continued behaviors of ill adults according to selected factors characteristic of perceptions of health status and reported health problem.

Source: Household survey, Abidjan, 2021 p: Significance test.

Source: Household survey, Abidjan, 2010-2011 *: Not significant.

It can be said that there is a tendency to turn to a health specialist relatively more often with the increase in the duration of the disease, but this does not imply that the most rapid effective action is sought, whether by the relative overuse of modern drugs or by the choice of service of medium to high hierarchical level.

More than the length of time since the onset of the illness as such, it is what has already been undertaken during this period that influences the continuation of the therapeutic itinerary.

Among the variables characterizing adults’ perception of health status, feelings of health and fatigue were, as expected, significantly associated with illness behaviors (Table 6(b)), in the sense that adults who felt tired and unhealthy used more care. In contrast, and as with children, feeling sad was not associated with these care behaviors.

Finally, the variables related to the characteristics of the disease (pain, worry, cessation of activities) are correlated with behaviors towards the disease. If the morbid episode is not painful, if it does not cause concern, or if it does not lead to limitation of daily activities, self-medication will be favored.

3) Care-seeking behaviors about facilitating or enabling factors

Regarding location variables, adults living in residential, working-class, or village neighborhoods were more likely to use health care services than those in poor neighborhoods (Table 7).

![]()

Table 7. Behaviors of ill adults according to selected facilitating factors.

Source: Household survey, Abidjan, 2021 *: Not significant.

At the stratum level, the differences widen between adults in the precarious area who used a health care service much less (18.2%) than the others (from 30.2% to 35.5%). This trend is confirmed at the neighborhood level, where only 16.5% of adults in the precarious southern neighborhoods consulted a health care structure, compared to 35.9% in the southern residential neighborhoods. The poor level of education (more than 47% uneducated) and the high unemployment rate (49%) could justify the low use of modern health services by households in precarious neighborhoods.

The length of residence in Abidjan also seems to have an impact on health care behavior. New residents (between 0 and 4 years of residence) were much more likely to forego care (29.8%) than those who had been living in Abidjan for more than 20 years (13.9%).

Active participation in a network, whether associative, confessional, or economic, reinforces the adult’s capacity to consult a modern care structure, but the degree of significance remains relatively low (p < 0.08).

Finally, owning a family pharmacy and knowing about the healthcare services available in the area are factors that facilitate the use of healthcare services. On the other hand, owning a motorized vehicle (moped, car) or being born in Abidjan is not significantly associated with health care utilization behavior.

The links between facilitating factors and health care utilization behaviors confirm that the socio-economic level of households is a barrier to the use of a modern health care service.

The cross-sectional analyses revealed numerous correlations between disease-related behaviors and a multitude of socio-demographic variables characterizing the child or adult and his or her household, the disease, and the contextual framework understood at the level of the concession, the neighborhood, and the housing stratum. However, at this stage of the analysis, it is still impossible to highlight the role and weight of socio-economic or spatial variables, whether they are predictive or enabling, in health care utilization behavior. This is why we chose logistic regression models to determine the relative contributions of the different explanatory variables.

3.3.2. Multivariate Analysis of Determinants of Household Health Care Use Behavior

The use of logistic regression provides a better understanding of the factors involved in the use of modern care and measures their importance while controlling for the effect of confounding factors that may have been identified in the univariate analyses.

Two main research questions will be addressed. What are the primary factors in defining the intention to seek care? What are the factors that act as barriers to seeking care? To do this, our logistic regression model will be based on a dependent variable: the use of a care facility. Logistic regression aims to predict the probability of a phenomenon, so here we are trying to predict the probability of using a modern care service based on a set of individual and contextual socio-demographic variables.

Several logistic regression models were tested. We worked on all the independent variables that were significant at the 20% threshold (Bouyer et al., 1995) [35] and now exclusively on the adult population.

The religion of the adult, the level of education, the knowledge of the surrounding health care offer, the presence of medicines in the household (family pharmacy), but also the perception of the disease through pain and anxiety are independently associated with the use of a modern service (Table 8). On the other hand, as we had already shown in the univariate analyses, the age and sex of the adult did not have a significant influence on the fact of going to consultation.

While the subdivision criterion was significant in the crude analysis, in the adjusted model, residing in a subdivided area did not significantly increase the chance of using a health care service.

Our results show that being a Christian increases the likelihood of visiting a modern health care service in case of a morbid episode.

The link between health knowledge (level of education, hygiene practices) and healthcare-seeking behavior is not always linear and straightforward, since the adoption of modern therapeutic behaviors does not fundamentally reflect progress in terms of health knowledge. On the other hand, knowledge of the surrounding health care offer appears to be an indispensable element in the care process. Lack of knowledge of the surrounding health care offer reduces the control of one’s neighborhood and one’s healthcare territory. Beyond strict knowledge of the health care supply, it is important to understand that the integration of the individual into the city, his or her neighborhood, and social networks play an increasingly important role, particularly in the city where family structures are changing, where the “large” African family is scattering and with it certain forms of solidarity and mutual aid.

The analyses also show that the existence of a small pharmacy in the household, as evidenced by the presence of paracetamol, aspirin, or nivaquine, significantly increases the probability of using care. Households already familiar with self-medication are therefore more likely to use a modern facility.

![]()

Table 8. Logistic regression on factors associated with the use of a modern health care service.

Source: Household Survey, Abidjan, 2021.

However, it should not be forgotten to mention that individuals primarily modulate their choice of treatment according to the illness, its duration, and its severity. The results of the logistic regression underline this trait. The greater the pain experienced, the greater the stress related to this illness, and the greater the probability of consulting a doctor.

Finally, while economics was often dominant among the constraining variables, we were unable to show it in this model. The lack of association between the economic factor and the use of the health care system in the multivariate analyses indicates that the majority of the households surveyed belong to a disadvantaged class.

4. Discussion

The study of therapeutic behaviors in the use of care underlines the predominance of home management of morbid episodes, particularly through self-medication. Patients, especially adults, administer traditional self-prescribed treatments that they alternate with treatments prescribed by the doctor or nurse until recovery. The predominance of self-medication in the management of an episode of illness has been noted in several studies on the use of health care in Africa (Richard, 2001; M. Harang, 2006 [17]; M. Ymba, 2022 [36]). The mix of behaviors makes this type of study complex. The recourses are varied, complementary, and sometimes contradictory, but do these practices constitute urban specificities? It is difficult to talk about specifically urban therapeutic practices without having conducted a similar survey in rural areas. Nevertheless, new care practices are emerging in the choice of facilities. While public sector facilities still play a major role in the choices of urban dwellers, as well as traditional medicine, recourse to modern health care services is diversifying, with care trajectories oriented towards the private and religious sector, particularly among the new bourgeois class in the city, and traditional services towards modern traditional medicine. However, in this context characterized by a plural offer, the use of self-medication is increasing. Self-medication limits the propensity to consult a health facility and delays the provision of care. It is due in part to poor knowledge of the surrounding health care offer, which has diversified and expanded in a context of rapid urban growth, but also to the precarious situation of many households. Self-medication thus appears to be a practice that competes with the use of a health care service.

The use of healers or traditional practitioners and dispensaries should not be considered in terms of rivalry, but rather in terms of complementarity in therapeutic practices, as our study has shown and as Fainzang (1986) [2] has stated.

These evolving practices are therefore proof of the existence of both complementarity and competition between the different types of care-seeking behavior. They are far from being archaic or irrational, as they are above all the expression of pragmatic choices because of the economic context of the majority of households.

When studied, the perceived meaning of illness is an important determinant of treatment choices (Sauerborn et al., 1996) [37].

We distinguished three degrees of severity: very severe, somewhat severe, and little or no severity.

We hypothesize that the relative frequency of therapeutic inaction and self-medication is greater the less or less serious the illness is considered to be, whereas the frequency of external recourse increases with the increase in perceived seriousness. In addition, there should be a preference for using the most appropriate health services in the case of serious illnesses.

In addition, modern medicines should be used more in cases of very serious diseases.

However, the patterns found are consistent with our hypothesis: the use of a modern health service is most frequent for the most serious illnesses.

Traditional recourse is reserved for serious to very serious illnesses. Therapeutic choices are therefore influenced by the perceived seriousness of the disease.

The almost total absence of recourse to traditional medicine for cases that are not very serious could also be explained by the fact that almost all recourse to traditional practitioners occurs after a stage of self-medication.

Thus, our initial hypothesis is verified: therapeutic inaction and self-medication decrease with the increase in the perceived severity of the disease, while external recourse becomes more frequent. This shows that a large proportion of patients consider that consulting a health specialist is a plus compared to treatment at home.

As noted elsewhere, the population is generally stoic towards illness. As a result, even illnesses that are considered very serious do not lead to immediate recourse to health services.

In addition, the diagnoses perceived by the patients influence the choice of treatment. According to Table 6(a), Table 6(b), self-medication as recourse is high for these diseases, but health services are used for care, particularly for ARI and malaria.

It is also widely accepted that the causes cited by families play a key role in the choice of care.

According to Richard (2001), “the identification of the disease is crucial, it allows us to understand its cause, but also to determine the most appropriate treatment to cure its clinical manifestations and to identify the resource person to provide care”. The symptom is the sign of a biological disorder, but it can also be the sign of a social disorder and this is why the patient’s entourage always looks first for the cause of the illness (Richard, 2001). However, it is difficult to demonstrate these links between the signs, symptoms, and causes reported by the families on the one hand, and the places of care used on the other.

Urban health care practices are therefore the product of multiple factors from different explanatory categories (predisposing factors, enabling factors, factors related to the characteristics of the disease), all of which contribute to the explanation of disease behaviors.

We focused on residential location throughout the analysis because we believe that this factor influences household use of care. The results of the univariate analyses often highlighted the role of the “neighborhood” factor at the expense of the subdivision and building density criteria. To continue this approach, we constructed a logistic regression model with this location variable. If at first the fact of residing in a given neighborhood was associated with the use of health care, by integrating other independent variables such as religion, level of equipment, etc., the association disappeared. The association disappeared. With the same level of equipment or the same religious affiliation, there is less of a neighborhood effect. We have therefore demonstrated a composition effect (individual socio-demographic factors) rather than a context effect (location factors). Further multilevel analyses would be necessary to investigate this question further and to assess the actual role of contextual factors in the use of health care in Abidjan.

Finally, although the economic aspect has often been dominant among the constraining variables, we have not been able to show it in this model. However, several studies have also shown the weight of these factors independently of the severity of the disease (Ayé et al., 2002 [38]; Taffa and Chepngeno, 2005 [33]; Baltussen and Ye, 2006 [39]). In other models we have tested, belonging to a household with a high equipment index has been associated with health care use. Belonging to a household with a medium equipment index, on the other hand, was never associated with the use of care service. The absence of an association between the economic factor and the use of the health care system in the multivariate analyses indicates that the majority of the households surveyed belong to a disadvantaged class. Taken together, these results lead us to draw several conclusions about health care utilization behavior.

First, we have seen that these behaviors are determined by the socio-demographic characteristics of the individual, his or her family, and contextual parameters, but also by the characteristics of the morbid episode, knowledge of the surrounding health care system, and attitudes towards the health care system. In this multifactorial context, it, therefore, appears “difficult, if not impossible, to attribute a univocal role to one factor” (Fournier and Haddad, 1995) [40].

5. Conclusion

All these results lead us to draw several conclusions about healthcare-seeking behavior. Firstly, we have seen that these behaviors are determined by the socio-demographic characteristics of the individual and his/her family and by contextual parameters, but also by the characteristics of the morbid episode, knowledge of the surrounding health care system, and attitudes towards the health care system. The study of therapeutic behaviors underlines the predominance of home management of morbid episodes, particularly through self-medication. We focused on residence throughout the analysis, because we believe that this factor influences the use of household care. The results of the univariate analyses often highlighted the role of the “neighborhood” factor to the detriment of the subdivision and building density criteria. To continue this approach, we constructed a logistic regression model with this location variable. If at first the fact of residing in a given neighborhood was associated with the use of health care, by integrating other independent variables such as religion, level of equipment, etc., the association disappeared. The association disappeared. With the same level of equipment or the same religious affiliation, there is less of a neighborhood effect. We have therefore demonstrated a composition effect (individual socio-demographic factors) rather than a context effect (location factors). Further multilevel analyses would be necessary to investigate this question further and to assess the actual role of contextual factors in the use of health care in Abidjan.