1. Introduction

Advertisement is a very common social cultural product in the highly developed commercial world of late capitalist society. Although it’s at the disposal of advertisers to employ all possible proper forms like video clips, fascinating pictures and pleasant sounds to convey and spread their information of products, it is language that plays the foremost role to put advertising information across. And in advertisements, the gender phenomenon has its significant representation too. Advertisements have taken advantage of the gender stereotype for a long time ever since it came into existence when the target consumer is one particular gender. And the study of the female representation of women in advertising is hardly possible if it was approached from a single point of view. As visual representation, it is connected with the issue of meaning and is approached mainly from the perspective of cultural studies in the postmodern consumer society. On the one hand, there is Baudrillar’s declaration of the implosion of meaning and hyperreality, the end of the social in the shadow of the silence of majority, which results in the view that audiences are the passive objects of media representation. On the other hand, there is Stuart Hall’s assertion of the production and contest of meaning in media representation and the generation of social difference by the imbalance of power relationship. To study the meaning of women in advertising, it is necessary to approach postmodernism in which power is located in discourse―the socially constituted language through forms of representation. When we consider advertising as one of the important forms of marketing in the process of consumption in the postmodern consumer society, it is inevitable to consider the consumption and meaning production, the economy of symbolic exchange in the postmodern world. Multicultural studies surged up in the 1990s around the issues of race, gender, sexuality, class and identity in especially the media or popular culture. It is connected with the intellectual work of British Cultural Studies since the 1960s. The key figures are Richard Hoggart, Raymond Williams, E. P. Thomson, who engage culture in the sense of mass or working-class culture as the genuine expression of the people in contrast to high culture or cultural elitism. Stuart Hall is another important cultural studies critics who constantly raised new issues of contest and has facilitated cultural studies into a political strategy over issues of race, gender, class, sexuality and identity, articulating for the cultural positions of the marginalized and the dis-empowered. Hall’s most important theorization is the idea of contingent negotiation of cultural products as a result of encounters and conflicts between different positions of culture, depending on Volosinov’s dialogism of cultural consciousness and Gramsci’s notion of cultural hegemony, incorporating semiotics into neo-Marxism. Specific examples are examined to have a deeper understanding about women’s images in modern markets from the perspective of post-modernism to give us a better picture about the great importance of women’s cultural images in our lives, how they are created to appear as realistic as possible, and how difficult it becomes for us today to distinguish between reality and illusion.

2. Literature Review

The literature concerning women’s culture representation shows that advertisers have traditionally exhibited a preference for using physically attractive models in advertising (Joseph, 1982) [1]. Research has revealed an overall “beauty is good” stereotype and advertising effectiveness is also positively affected by the attractiveness of the models used (Halliwell and Dittmar, 2004) [2]. Some global companies have promoted new ideas of femininity. Dove ever launched a communication program themed with “Real Women Campaign” which focused on real beauty, aiming to challenge the way in which women were portrayed in mainstream advertising (Howard, 2005) [3]. This campaign increased the sales of advertised items by 700% in just seven months. Following this success, the company even decided to make women feel beautiful everyday by challenging today’s narrow, one dimensional view of beauty and presenting a multidimensional view of beauty.

Women’s image in media advertising has actually explored by many scholars from various angles. Cortese (2007) [4] discusses the image of attractive women typically featuring on printed advertisements and argues that “she is a form or hollow shell representing a female figure”. He considers the images of women featuring in advertisements to be distant from reality, and discusses the negative implications of this situation to self-confidence of representatives of ordinary female population. Ross and Byerly (2008) [5] argues that traditionally media advertisements have positioned women as passive and submissive. Cheng and Chang (2009) [6] relate to women’s image in media advertising to sex appeal and it is not likely to change as long as the future we can see. Abel et al. (2010) [7] holds that attempts to study integrated images of women in advertisement in various forms increase significantly nowadays. McAllister and West (2013) [8] studies the reasons why women’s images are more often used more than their counterparts in opposite gender in media advertisements. And it is believed to be much easier to communicate human being’s emotions like happiness, anger, curiosity, etc. through female images than images of men. In the research done by Ali (2014) [9] entitled “Women’s Objectification by Consumer Culture”, women feel more at risk towards their physical appearance in a culture. Women are the most portrayed in and advertisement to show the meaning of beauty to consumers (Das and Sharma, 2016) [10]. What’s more, women’s traditional roles were stereotyped to be at home and uneducated as those who are inferior in terms of judgement and knowledge than men (Kumar, 2017) [11]. And, quite often, women’s beauty is used to promote cosmetics by highlighting the sexiest and most crucial parts of women’s body to the target consumers. However, a research by Zachari et al. (2018) [12] states that new generation are not looking forward with advertisements that showing only physical appearance of the models without including any other important information about the services or products offered. Other than stereotyping women as definition of beauty, women were as well stereotyped as weaker than male whom were seen as more dominant creature and believe to be able to handle women’s personality (Hust, Rodgers, Cameron and Li, 2019) [13].

3. Theoretical Foundation

In a commercial society in which all kinds of powers struggle for its existence and dominance, women as a cultural representation and an importance social force witness the gradual change concerning its culture identity and social construction, which indicates that the social and cultural meaning of women is a dynamic, fragmented construction due to the destabilization of social production. It is widely accepted in critical discourse analysis and post-modernism that the in-depth decoding of language structure helps the deciphering of cultural signs and the structure of social reality. Thus, in the theoretical construction of cultural analysis, there does emerge a linguistic orientation. Language, as a system of social signs and cultural representation, has been rendered as the focus of philosophical concern. The social and cultural meaning of women is not only a question of how women are spoken and understood but a question should be explored from the linguistic/semiotic point of view. In other words, the cultural representation of women should be approached within the framework of the notion of representation―the use of language to express meaning. Representation is considered as the production of meaning through language according to the constructionist mode in the contemporary world. It is a symbolic practice and a process in which language operates to form meaning. “language and systems of representation do not reflect an already existing reality so much as they organize, construct, and mediate our understanding of reality, emotion, and imagination” (Sturken & Cartwright 2001: p. 13) [14].

The study of cultural representation should be historically specific. Thus it is important to map out the historic condition in which advertising is studied so that their meanings can be better explored. With the postwar affluence and the rise of the middle-class as the main body in late capitalist society since the 1950s, the late capitalist society has entered the postmodern period. There occurred a shift of focus from production to consumption. Meanwhile, new technologies provide more possibilities for the prosperity of cultural industry or media simulation.

4. Women’s Image in Cultural Representation

4.1. Women’s Image in Commercial Discourse

Cultural representation prevails and visual signs can easily be spread all over the world with the global market. Goods have become “commodity-signs” (Baudrillard, 1998) [15] that embody meanings in late capitalist society. With the stylization of life and the promotion of leisure, there is the pleasure of consumption, of dreams and fantasies, desires and social status. Cultural products are being justified by the utility or efficiency for profit or wealth. As Jean-Francois Lyotard says, “The games of scientific language become the games of the rich, in which whoever is wealthiest has the best chance of being right. An equation between wealth, efficiency, and truth is thus established.” And as Stuart Hall acknowledges: the postmodernist society is essentially controlled by cultural power. The capitalist society has witnessed great transformations since the 1960s. Social, political and cultural disturbances erupted in the sixties to sweep through the whole capitalist world such as: environmentalist movement, black civil rights movement, the Feminist movement, gay and lesbian right movement, student protestation, anti-vietnam war strikes, youth rebellions, etc.

Moreover, Judith Butler, in her famous Gender Trouble (1990), based on Foucauldian discourse, sees representation, especially media representation, as playing the key role in forming gender identity: first forming the core of femininity and then compelling women to act as represented. According to her, women are culturally constructed and gender identity is performatively formed. As she specifies (1990: p. 25) [16],

gender proves to be performative…that is, constituting the identity it is purported to be. In this sense, gender is always a doing, though not a doing by a subject who might be said to preexist the deed…. There is no gender identity behind the expressions of gender; that identity is performatively constituted by the very expressions that are said to be its results.

Women are objects of socio-cultural construction. Without cultural construction women are but a void. As Butler is strongly anti-essentialist, she denies any solidity of the meaning of women. Women are seen as products or subjects as subordinate to patriarchal culture.

When exploring the power relationship in constructing the cultural representation of women in advertising, a major objective is the study of the identity of women. While the identity of women as the white heterosexual body of sexual appeal is examined, it is argued that the identity of women represented in advertising is fragmented, not only because of the multiple identity of resistance politics but also due to the increasing power of the audience/consumers, who construct their own meanings/identity according to their needs, pleasure and social conditions in relation to race, gender, identity. Consumption becomes the crucial process for meaning construction, which offers the opportunity for the reconstruction of the meaning for individual woman in everyday life. Therefore, the female identity is more fluid than rigid. Different meanings constructed in advertising are measured in relation to race, gender and sexuality and identity. Women in advertising are found out to be represented as white, heterosexual pretty body with presumably sexual appeal. Female images other than this category are marginalized: they are characterized by fetishization, sexualization, fragmentation, objection, underrepresentation, trivialization, negation, commercialization, in addition to a racialized and gendered representation. Female representation in advertising is saturated with the power of domination by the social institutions which represent the white supremacist capitalist patriarchy of late capitalist society, which attempts to maintain its social, cultural, economic and political power by fabricating and dominating the Other Half. As we all know, advertising is also a realm where multiple powers contest for existence. The voices of the oppressed and marginalized are also articulated in the representation of advertising. Not only are there changes in the representation of women, but there also appear new elements which represent resistance to the dominant discourse of women in advertising by the subculture images, lesbian images, transgender images as well as female images of multiple, ambivalent meanings, which are commercialized by capital in order to magnify the market. In addition, this characteristic of power politics in advertising illuminates the empowerment of women in consumer society as well as the resistance strategies to stereotypical representation of advertising.

4.2. Women’s Image in Commodities

To understand the meaning of advertising, it is important to understand photography as a new visual code (Sontag 1977: p. 1) [17] signifying meanings. First, photography is cultural representation which produces meanings instead of reflecting the truth or reality. And Stuart Hall once said: “There is no such a thing as photography; only a diversity of practices and historical situations in which the photographic text is produced, circulated and deployed.” Photographic images are not only discourse, but they are also for the pleasure of consumption. This is another feature of advertising images, like other forms of western visual art. Annette Kuhn first links photographic representation with the discourse of women and the consumption of female images.

It is no coincidence that in many highly socially visible (and profitable) forms of photography women dominate the image. Where photography takes women as its subject matter, it also constructs “women” as a set of meanings which then enter cultural and economic circulation on their own account. …Cultural meanings centered on the signifier “woman” may become relatively fixed in use: but a certain range of meaning is still available (1985: p. 19) [18].

What Kuhn means is that in visual representation or in advertising women are not only signified with cultural meanings as man’s other half, but also for the pleasure of sight, that is, for male consumption. Annette Kuhn summarizes the power of body images in advertising (and other visual forms) as revealed through the objectification, and the commercialization of women. Not only does she critique the representation of the female body as the male object of consumption, but she also highlights the commercial concern for sales in relation to these body images: while the consumption is dubious, there is the imbalance that it is more of the consumption of the female image than that of the product it sells. In other words, advertising depends on the meaning of women to promote consumption just like selling goods by selling femininity. That is why Donald M. Lowe (1995) [19] says late capitalism depends on the exploitation of the female body for capitalist accumulation. The representation and consumption of the female body becomes the most important feature in contemporary advertising.

Visual images of women in the contemporary society are not only for the pleasure of male look, females also have the pleasure of looking at females, as claimed by Jackie Stacey [20] in Desperately Seeking Audience. This is, of course, connected with the rising power of women due to feminist articulations. The female body, sexually presented as body ideal, good for male look as presented, also meets women’s need and pleasure of looking (due to lesbian experience, sense of self fulfillment, the need in social and professional life, or simply the pleasure of looking/consuming). The need and pleasure may be various, but women’s sense of power and autonomy is important. In other words, what to consume depends on women’s individual choice. So in studying the representation of female images and the specularization of the female body, the female body is not treated as merely patriarchal discourse of the Other Half for male look, but as plural language embodying complex power relationship through photographic construction. The female body also speaks of female experience, the rebellious language and the transgressive pleasure. It may as well be the embodiment of women’s empowerment in the postmodern society characterized by ambivalence and uncertainty.

Robert Goldman’s commodity feminism (1992) [21] stresses the pluralism of meanings, as accounted in detail by Mike Featherstone when he describes the meaning of the body in one ad:

This advertisement demonstrates how women are now being portrayed as choosing to be sexual objects because it suits their liberated interests. Power imbalances are redressed in terms of commodity consumption, in this case, in terms of underwear and personal appearance choices. Freedom and choice are conjoined with images of sexuality and commodities. (Johnson ed. 2001: p. 70) [22]

The female body in advertising entails both power domination and selfempowerment, a norm and a free choice, as an object of consumption and for women’s consumption. This ambivalence of the female body shows the complex meanings of the body and complicated power relationship in postmodern society.

As we take advertising as a particularly thriving phenomenon in late capitalist society, a society of affluence and apparent prosperity, and in the process of consumption (circulation of goods), we have to take into consideration products, and their role in representation, as advertising basically, as Judith Williamson remarks, “has a function, which is to sell things to us” (1978: p. 11) [23]. Baudrillard gives an elaboration of the symbolic aspect of the product/goods, in the process of consumption. Methodologically, the meaning of products can be investigated by the analysis the product types. The total sample of advertisements is rearranged according to types of products. They are roughly classified in ten types (Table 1).

The result gives a very clear message that the cultural representation of women is mostly associated with fashion and beauty products. The numbers also clearly tell the readers that women are often connected with domestic products and household affairs. The theory of association denotes that women are first defined by their physical feature: a beautiful body, striving for youth and body attraction. On the other hand, the cultural connotation can be pointed out that women are understandably disconnected with the formal work, technology or

![]()

Table 1. Ten types of commodities advertised by women.

(From Baudrillard, Jean, (1998) [15] ).

intelligence. To summarize, advertising presents woman primarily as body of attraction and then as domestic creature with low intelligence and power, which means primarily a body of appeal, and man’s subordinate.

4.3. Women’s Image in Post-Modernism Perspective

In the perspective of post-modernism, female images can produce much informative meaning combined with cultural factors. The female images are taken as signs which have the underlying the meanings in late capitalist society. There are more complicated ways in cultural representation to connote the images and social meanings of women of different ethnicity, age groups and sexuality preferences. Various ways of representation are employed in advertising such as: sexualization, marginalization, racialized representation, fetishization, fragmentation, negation or underrepresentation, etc.

Women are displayed as objects which can be taken advantage of sexually. All beautiful and sexy parts of female body are fragmented, highlighted and framed in close-ups to indicate tempt. An ad for moisturing lotion is a very good example in point. A close-up of a nude without a head of a well-chosen female image to highlight the shiny moist skin. Women are interpreted as something with no brain or intelligence but a sign of desire. Koebel brand champion is another good example. Woman’s body is directly used to sell the lure to man’s consumption. Women accounts for a majority of fragrance consumers. In a fragrance ad, the shape of bottle container of Chanel fragrance simply duplicates the woman’s body to exaggerate of the flow of the female desire. As we all can easily notice, the female images of women are usually attractive, nudes or half-nudes for sexual attractiveness in many ads. (e.g. Figure 1 and Figure 2 in Appendix). The cultural representation featured by women as an object of temptation and desire shows the visual entertaining, sexual consumption, body-commercialized tendency, and the dehumanizing reality of women. In another ad for advocating diet, a slim, beautiful and charming female figure is lively presented to show it is a sure bait for man (boyfriend) while a bulging baggy body is displayed as something undesirable. The sharp comparison gives its audiences much information for their dietary choices and the female body is presumably considered as something transformable to meet the commonly-held social norms and men’s tastes. And bodybuilding and training business usually make attractive women their spokesperson and a method to promote their business. The healthy and fit women’s bodies are invariably displayed as sexy attractions. In late capitalist society, everything is regarded as consumable. Although, there have been much progress in society concerning gender equality, women are generally taken as decorative objectives, as beauty for man’s pleasure and an allurement for men to spend money.

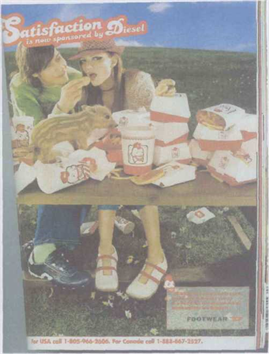

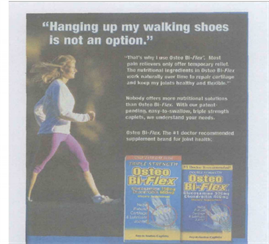

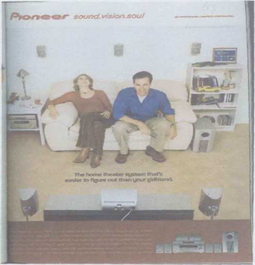

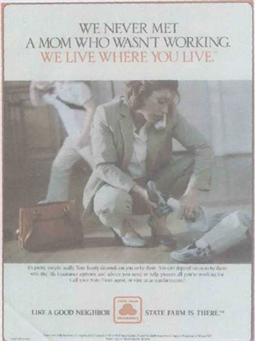

It’s well-known that the female images in most cultures are always associated with flowers, showing women’s cultural equivalence of woman to flower, which is sensual, inviting, and pleasurable, as decoration and for consumption. Women are also quite often portrayed as something changable like water or other fluids, green-colored, yellow or orange-colored, indicating fluidity, instability and irrationality while male images are mostly connected with mountains, rocks, deserts indicating roughness, firmness, and stiffness. Women can also be depicted as negative images. In the ad (Figure 3 in Appendix) for the Hidden Bailey brand ranch, the female model surely enjoys the food, but the white taint beside her mouth can be interpreted by postmodern linguists as greediness and uncivilizedness. What’s more, women are sometimes even demonized. In the ad entitled “Satisfaction is now sponsored by Diesel”(Figure 4 in Appendix) which highlights the Diesel brand footwear worn by the male and female characters, the woman model is pictured as with a tigerish mouth and monster-like eyes. She is being fed by a man with a spoon. Mountains of chips are put just before her on the table, gazed by a squirrel. The linguists can easily read the connotation of the ad. The woman is equivalent to the squirrel and the feeding man suggests the greediness and laziness of women and their dependence on men. Women are also culturally labeled as inferior, vulnerable, and in need of some special medical treatment. There are some diseases like arthritis, aching joints, heart disease, allergy, depression which surely affect both men and women. But in most medical ads, we usually find that women are represented as sick (Figure 5 in Appendix) and need medicine. And almost in all ads for anti-allergy medicine female models are used for advertising, meaning that women are sensitive and easily attacked (Figure 6 in Appendix). Here, women are labeled as an inferior and vulnerable group and medicine becomes their support to a better life, which can be culturally deciphered as the power of controlling and curing. In another sense, women are defined as incapable or as a useless object in terms of their connection with modern science and mechanic technology. In the ad “Pioneer, sound, visual, soul”, the man, taking up most part of the sofa, leaves his girlfriend aside pretending to sleep and totally indulged himself in the pleasure brought by the Pioneer brand cinema system, with the comments in the middle: the home theater system is easier to figure out than your girlfriend (Figure 7 in Appendix). Watches are also very popular commodities all over the world even in a modern society in which watches cannot hold their practical value like what they ever did in the past. In the ad (Figure 8 in Appendix) for Citizen watch, a woman is shown to be attracted by a battery and look at the other side while, as a matter of fact, the watch never needs one. The cultural amplification of the power in machines and the negative images of woman ties women to images of being technology-void, useless, less capable and marginalized in the modern society. As we can see, technology is the first power and it is presented as the symbols for power or masculinity in late capitalist society. The late capitalist society also witnessed more and more career women in many industries and families. They surely make their own contribution to the society in their own ways, but career or working women still tend to be trivialized. They are still culturally represented as unable to strike a balance between doing a good job and taking care of their families (Figure 9 in Appendix). On the other hand, housewives are purposely depicted as happy and contented with their place at home taking care of their children. In particular, active young women are represented as sexually aggressive instead of professionally competent. And the young active professional women, are usually doing low-position jobs (Figure 10 in Appendix) with a high-position male manager. In late capitalist society, racial problems can never be ignored but they usually won’t come up with a result desired by all the involved sides. In many ads, black women are racialized culturally. Racial discrimination reveals itself in the camera technology with the ad portrayal of images. Even in some pictures of ads with women of different culture backgrounds and skin colors, black woman shall be marginalized such as being placed in the distance with the centering of the white. The ad “Holiday Pleasure” (Figure 11 in Appendix) aims for Newport brand cigarette with a number of people of different skin colors, but the black man and woman are taken as background or at the margin with a white male smoking a cigarette in the center of the picture, which clearly implies the marginalization of blacks. The racialized position can also be enhanced by showing white privilege in ad portrayals. In Figure 12 in Appendix, a white respectable woman is delivering an academic award to a young black woman who smiles happily and gratefully for the honor granted her. The white woman is clearly in the dominant position. Furthermore, a large-sized white male body with solemn faces is presented as the background for the awarding ritual. This ad simply represents the white, male-dominated academic world in the late capitalist society as well as the hierarchical relationship of race and gender.

The society shows much negative biases against the old and middle-aged women. The overrepresentation of young beautiful female body itself is good evidence to show the underrepresentation of the mid-aged and the old, especially the black old women. Aging is thought as a negative quality in life. Some problems will come along with age. Wrinkles is a good example but they are represented as something hateful instead of something natural in an ad for anti-wrinkle oil (Figure 13 in Appendix). The images of the middle-aged or the elderly are most likely to be employed for medicine products, the medical service or insurance services. And only one case of lesbian representation is collected in the course of data searching. Lesbians are assumed not as happy as heterosexuals. The absence of the images of lesbians of different complexion indicates racial prejudice. The meaning of woman is constructed as unbalanced in advertising: there is the over-representation of young, white, traditional, middle-class, heterosexual women of body attraction, on the one hand; the under-representation of woman other than these stereotypes. And women are not presented as independent and autonomous beings, but are presumably depicted as sexual objects with only body appeal for male consumption.

Images portrayed in advertising are seen as a process of meaning production. Judith Williamson (1978) says, “advertising creates a structure of meaning” [23]. Both Williamson and Sut Jhally (1990) [24] see advertising images as codes which produce meaning as the use value of products which functions determinately in the process of circulation. The British Cultural Studies critic Stuart Hall sees advertising/media images as a process of encoding at the moment of production--a process of the organization of knowledge from social relations and then distributed to audiences and preferred to be accepted. To Hall, discourse is necessary in media representation. Language mediates representation and reality: reality as both source of representation and a constitution as a result of it. As Hall clarifies, the production process is not possible without its discursive aspect: it, too, is framed throughout by meanings and ideas: knowledge-in-use concerning the routines of production, historically defined technical skills, professional ideologies, institutional knowledge, definitions and assumptions, assumptions about the audience and so on frame the constitution of the programme through this production structure (Hall et al. eds. 1980: p. 129) [25]. In other words, discourse/language plays the key role in visual representation, as an articulation of social relations and a tactic for social control.

Furthermore, Hall sees the representation of advertisements as completely a discursive process which is historically and culturally specific rather than a reflection of truth or reality:

Discursive knowledge is the product not of the transparent representation of the “real” in language but of the articulation of language on real relations and conditions. Thus there is no intelligible discourse without the operation of a code. Iconic signs are therefore coded signs too, even if the codes here work differently from those of other signs. There is no degree zero in language. Naturalism and realism―the apparent fidelity of the representation to the thing or concept represented―is the result, the effect, of a certain specific articulation of language on the “real”. It is the result of a discursive practice.

(Hall et al. eds. 1980: pp. 131-132) [25].

Hall’s view of representation can be used to study female representation in advertising, to discover discourse/language embedded in advertising images by sorting out codes―the visual signs or the traits of femininity. To Stuart Hall, discourse is necessary in media representation. Language mediates representation and reality: reality as both source of representation and a constitution as a result of it. As he ever stated: “The production process is not possible without its discursive aspect and it is also framed by meanings and ideas such as knowledge-in-use, historically defined technical skills, professional ideologies, institutional knowledge, definitions and assumptions, assumptions about the audience and so on frame the constitution of the programme through this production structure (Hall et al. eds. 1980: p. 129) [25].

With an all-round analysis of female images in advertising, we can conclude that meaning construction is a complex process in the late capitalist society. The cultural representation and social meaning of female images is more than a mere construction by the supremacist capitalist patriarchy. There are multifaceted, ambivalent meanings in the images, which are heavily dependent on the decoding activities of the audience in the process of consumption. Female consumers are also supposed to be active readers who can construct their own meanings of images. There is surely more than one contributor in meaning construction: advertisers first construct meanings on their own consumption which are intended to be consumed by their target audiences. Meanwhile, consumers will create their meanings or identities while rejecting the socially imposed meanings or identities. These meanings or identities created by audience or consumers are then appropriated in advertising by social institutions in order to maximize the market.

5. Conclusion

After the statistical and semiotic research, the discourse of women in the representation in advertising is argued as the identity constructed to normalize female images in late capitalist society. And the female identity naturalized through discourse is seen as the dominating power over women for capitalist social, cultural and economic control. The two-way flow of meanings indicates two processes of negotiations. The first process of negotiation takes place in the process of decoding where audience or female consumers construct the meanings of advertising images by positional reading based on their own needs, pleasure and social circumstances. On the other hand, negotiation made by the advertisers in dealing with the meanings or identities created by consumers also plays a very important role. And the negotiations in two sides show power as dynamic. Those in dominant power cannot always secure its power of domination, because it is in dominant position at present. To be specific, the various social forces are in a dialectical and symbiotic relation: coexisting but contesting, negotiating, incorporating, and possibly cooperating with each other while mutually rejecting, each with its own position. That’s why the female images in advertising cannot be summarized by any abstract essence, but, in nature, it is diversified and fragmented. Women are far from being spoken by this discourse but are able to construct their own meanings of self according to their positions as well as their need and pleasure in life. The process of decoding/reading connotes their power in constructing their identities in relation to race, gender, class, and sexuality. Power falls at the micro-level in contemporary society in the everyday experience instead of being imposed from the upper macro-level. Culture in late capitalist society is not characterized by any one fixed center but is a culture of multiple centers with different forces mutually influencing each other. All in all, female images in late capitalist society cannot be defined by the dominant discourse such as supremacist capitalist patriarchal culture, imposed by ruling social institutions. It is multi-centered and full of resistance and articulations of positional politics in relation to race, gender, class, sexuality and identity. Individuals and ethnicities are articulating for their own end from their own circumstances. Dialogues are occurring everywhere at the site of individual consumers who are active creators of meanings. Power politics reigns supreme. It can be seen that capitalism plays the key role in incorporating this cultural politics. Advertising is the promotion of goods through the consumption of meaning. Cultural representation of female images is the utility value in consumption.

6. Limitations

The study develops a cultural and reception analysis based understanding of images of women in advertising. It must be pointed out that the study is an empirical study in nature and intends to offer a market perspective in understanding women’s image in advertisements rather than to prescribe how women’s image should be portrayed or understood. And the data collected in the research are quite limited due to the small scale of the research. We still have to point out it’s quite understandable that the same advertisements generate multiple readings, and we just explore them from one perspective. Furthermore, actually not only the female images in the ads but the overall stories of the ads can be decoded differently by various interpretive communities. Further studies need to examine an overall image and those advertisements that motivates opposite interpretations from the traditional views.

Appendix

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13