Effect of Gender of Tunisian Teachers on Teaching Practice during Gymnastics Sessions ()

1. Introduction

Author collectors (Lenoir, 2009; Lenoir, Larose, Deaudelin, Kalubi, & Roy, 2002) demonstrate that the educational intervention is multidimensional, combining the didactic, psychopedagogical, organizational and institutional and social dimensions. The authors explain that the educational intervention is based on a device linking the interaction between two types of constituent mediations of the teaching-learning relationship. Cognitive mediation, for which the subject is responsible for establishing it with the pupil, and pedagogic-didactic mediation, which is the responsibility of the teacher, this mediation is qualified as an educational intervention. It is on this mediation that the work of this research is based. Following these multidisciplinary works on the analysis of the teaching practice, Altet (2002) affirms that this analysis deserves to take into consideration, at the same time, the pedagogical and didactic management of the contents as well as, the interactivity in the context where produces the teaching practice (in situation) and to understand the meanings that emerge in situ. These are taken into account by the actor. What is played out in situ during the course of the teaching-learning situation must be taken into consideration to understand the educational intervention of the teacher. Pelletier and Jutras (2008) and Visioli and Petiot (2015) consider improvisation to be “a creative action” and argue for improvisation training or what Perrnoud (1999) calls training in dealing with the unexpected. For these authors, it is wise or even necessary to learn how to manage the unexpected and adapt to the reality of the professional situation. The context and the object of the teaching of physical education (PE) are particular, on the one hand, the places of teaching are multiple (sports field, sports hall, swimming pool) and on the other hand, the contents taught are also part of a particular context, linked, on the one hand, to the various fields of knowledge (psychology, sociology, physiology, etc.) and on the other hand, they are part of the social practices of reference (Martinand, 1981). For Sarthou (2003) teaching PE is certainly teaching physical and sports activities (SPA) to induce, on the one hand, to the educational and didactic reflections of the teacher and on the other hand, to contribute to the education, psychomotor, socialization and autonomy in students. According to Saury, Ria, Séve, and Gal-PetitFaux (2006), to achieve targeted transformations in students, the PE teacher prepares environments likely to allow student learning. Thus, whatever the reference learning theory is used, the preparation of appropriate and effective spatiotemporal and material devices is at the heart of his professional activity. For Brun and Gal-Petitfaux (2006), it is on the temporal and spatial organization that the lessons are strongly based. The dynamics of teacher-student and student-student social interactions are organized by the topography of the premises. The architectural configuration, the spatial arrangement of the students and the objects present are likely to orient the form of the activities taking place in the classroom. Classroom management appears more and more at the “heart of the teacher effect” (Martineau, Gauthier, & Desbiens, 1999), student learning depends on it and is not limited solely to didactic dimensions. The classroom management skill turns out to be a complex, dynamic and multidimensional activity (Legoult, 1999). Chouinard (1999) states that academic success is mainly influenced by classroom management and that the latter’s efficiency makes it possible to optimize the time devoted to learning and ensuring the smooth running of educational activities. So, therefore, you have to manage your class in such a way as to meet the needs of the learners. Lessard and Schmidt (2011) state that the teacher must establish a certain balance between several tasks and functions in order to really help the student to develop his skills. The teacher must take into consideration the class group but also the individual differences, he must also allow the cognitive and socio-emotional development of the pupils he must promote and maintain a climate conducive to learning while using pedagogical approaches fulfilling the various student needs. Generally, the action of the PE teacher, during his daily professional practices, has two primary aims of a didactic and pedagogical order (Doyle, 1986; Leinhardt, 1990; Shulman, 1986a, 1986b; Vors & Gal-PetitFaux, 2008). An aim of building knowledge and know-how among the pupils on the one hand, an aim of management and organization of the class, on the other hand, Coordination and complementarity are compulsory between these two aims (Gal-PetitFaux & Vors, 2008). In addition to pedagogical and didactic management, there is the management of the distance of the teacher’s placement during the practical sessions (BenChaifa, Naceur, & Elloumi, 2018a), and his emotional management (BenChaifa, Naceur, & Elloumi, 2018b). The non-verbal communication of teachers in the field translating and expressing, emotions, feelings, to assist the verbal communications of the speakers towards their learners (Boizumault & Cogérino, 2010). By non-verbal communication, Genevois (1992) designates facial expressions, gestures, gaze, postures, clothing that accompany the verbal communication of the individual. The PE teacher uses his body to communicate certain information (Boizumault & Cogérino, 2010, 2012), during his interactions with his students. He uses verbal non-verbal communication to ensure student learning. According to Genevois (1992), it is within verbal and non-verbal elements that learning is constructed. Burel (2014a) affirms that other than the mission of the PE teacher to improve the motor skills of the pupil which is played directly on the body by the physical contact is added to the evolution of the pupils according to spatial configurations, complex temporal patterns favoring more proxemics categorizations. For Boizumault and Cogérino (2012), the body of the teacher is often used, during his didactic-pedagogical interventions, at various distances. Sensevy, Forest, and Barbu (2005) define didactic distance as “a function of Euclidean distance, body orientation and gaze orientation” (Forest, 2006: p. 78; Sensevy et al., 2005: p. 266). The educational environment is an environment rich in interpersonal interactions, thus promoting the birth and development of emotions (Cuisinier & Pons, 2011; Rusu, 2013). “Teaching is an emotional practice” (Hargreaves, 2000). Emotions influence learning processes and interpersonal relationships (Cuisinier & Pons, 2011; Gendron, 2004; Hargreaves, 2000; Rusu, 2013). Cuisinier and Pons (2011) go so far as to consider emotions the hidden face of the didactic triangle. Emotions, either positive or negative, are known, respectively, to facilitate or hinder learning (Cuisinier & Pons, 2011) and to engage or hinder the development of interpersonal relationships (Rusu, 2013). Hargreaves (2001) recommends taking emotion into consideration during the learning process and academic success. Several authors (Cuisinier & Pons, 2011; Gendron, 2008; Hargreaves, 2000, 2001; Lafranchise, Lafortune, & Rousseau, 2007; Letor, 2006; Puozzo, 2013), confirm that teachers’ emotions impact their students’ results. Chevallier-Gaté (2014) insists on the fact that the teacher must mark an authentic presence, by articulating its different facets, cognitive, affective and bodily, and make them practically manifest, to oneself and to the other. Letor (2006) confirms that by a good management of these own emotions, of those of these pupils, the teacher can favor a good climate of learning, attracts the attention of the pupils, contributes to their commitment, maintains their effort, manages their behavior and makes them understand the material. Several studies (Boizumault & Cogérino, 2010; Burel, 2014b; Ria & Chaliés, 2003; Ria & Durand, 2001; Ria, Saury, Séve, & Durand, 2001; Visioli & Ria, 2007; Visioli, Trohel, & Ria, 2008) have been carried out on the emotional dynamics of teachers in the field of physical education, underlining the omnipresence and the dynamics and the role of emotions in and on the daily professional action of teachers. Visioli et al. (2008), confirm that the PE lesson is a favorable environment for the birth, development and exchange of feelings and emotional expressions, whether positive or negative, between the teacher and his students. The propagation of emotional expressions is basically done through the body of the actors. Physical engagement is an important source of exacerbating emotions to consider during PE lessons. These authors insist that emotions should be considered as a “relational phenomenon”. Practically in physical education, for several authors (Visioli & Ria, 2007; Visioli, Ria, & Trohel, 2011; Visioli et al., 2008), it is by continuous adjustments of their professional gestures: postures, gestures, displacement placement and a particular interpersonal proximity, that teachers exploit a wide range of emotions and disseminate, in particular, through these non-verbal behaviors what they expect from students and they obtain various effects on the latter. Hess (2004) draws the gap between voluntary deception and the display of simulated emotion, which is none other than the will to cheat. During a deception, the emphasis is on the sender’s desire to deceive the receiver, but the simulation occurs for several healthy reasons among others, to increase self-esteem or hide an emotion, to raise appropriate behavior, without having this desire to cheat. or Visioli and Ria (2007) teachers stage their emotions to have an impact on students, it is a kind of “theatricalization” of emotions, over time they learn to camouflage and put on scenes that express emotions that do not correspond to what is actually felt (Visioli et al., 2011). The use of emotions to have an impact on students for educational purposes allows several authors (Visioli & Ria, 2007; Visioli et al., 2008), to consider emotions as pedagogical artifacts for educational purposes.

2. Methodology

During this research, the main questions are: the gender of the teacher intervenes in the teaching practice during the course of the gymnastics sessions? At what level is the difference between the teaching practice of a male teacher and a female teacher? To answer these questions, thirty PE teachers were involved in this study, divided into 15 men and 15 women. The voluntary criterion was essential here and the participants were all informed in advance of the framework and the conditions of the research. To make this study a reality, two investigative techniques were used: firstly, gymnastics sessions were recorded at the rate of two sessions per teacher. These sessions had an average duration of 55 minutes. The teachers’ interventions were filmed in situ, using three digital cameras, one of which was placed on the teacher’s head but which allows him total freedom of movement, in order to collect all verbal communications and all the angles targeted by the teacher. A second camera is manipulated by the researcher who follows all the movements of the teacher at a respectable distance, thus guaranteeing wide shots capturing all the interventions of the teacher with his students. A third camera mounted on tripods, in a corner of the gymnasium, provides very wide framing shots, making it possible to view the teacher and all the students at all times. Secondly, self-confrontation interviews, which serve to document the pre-reflective experience of the actor (Theureau, 1992), were carried out immediately after the practical session. A laptop computer and a video projector allowed the viewing and projection of the videotape of the recorded lesson. A tape recorder allowed the audio recording of the post-lesson interviews. The playback of the videotape is interrupted by the pause, advance, rewind functions at any time at the request of the teacher or on the part of the researcher. The teacher is confronted, at every moment, with his actions which he is invited, by semi-open questions and based on the video, to explain what he was doing, thinking, taking into account to act, perceived, felt (Vermersch, 1994), without asking him for justifications. For data processing, there were transcripts of self-confrontation interviews. Then the transcripts of the practical sessions in the form of a two-part table, for part 1 actions of the teacher and students and for part 2 verbatim of the teacher., Finally, the MB-Ruler software was used to measure the interpersonal distance according to the different placements of the teacher in relation to the student during four moments of intervention defining the different placements of the teacher. In a second step, the verbatim of the recordings as well as the answers of the interviews have been submitted to the content analysis technique in the form of grids containing the pedagogical, didactic and emotional management according to the gender of the teacher. In the last step, the data collected was submitted to the calculations of the percentages for, as well as, the calculation of the average for the interpersonal distances.

3. Results Analysis

3.1. Detailed Analyses of Pedagogical Management According to the Gender of the Teacher

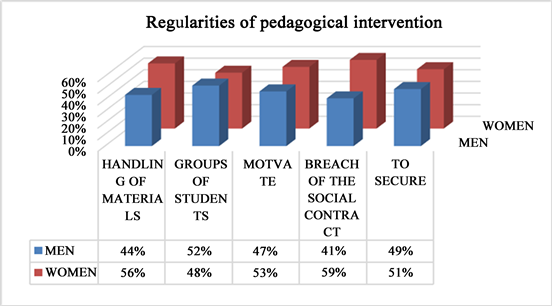

The parameters used by all the teachers, during their daily practices as being regularities of intervention for the pedagogical management, were subjected to the percentages. The results are schematized by the following histogram:

According to Histogram 1, the female teachers use to move and handle the teaching materials reassure and motivate the pupils more than the male teachers

Histogram 1. Regularities of pedagogical intervention.

during the practical sessions. They are more confronted with the breach of social contract and they use devious means to have the class in hand. During the self-confrontation interview, a woman commented “I have to get closer to the students, tap on the shoulders for encouragement, it gives them a lot of work to do, I try to give the maximum so that the students manage to succeed, I get closer where something can affect the safety of my students when I address the students from afar I feel that they are not motivated look there, I got closer and I even changed the language I encourage them more and there was a positive response and better performance from the students, if not for discipline, I always remind by the note by what I know very well is the pet peeve of the student is the grade, the student will put more effort into improving his execution, he becomes more motivated, to tell the truth it does not work all the time, in this case, I try to take the student aside to convince him or else I make him responsible if not, it’s not easy to master today’s young people”. On the other hand, men change shape and manipulate student groups more than women. One man commented while viewing the videotape of his practice session “if you give a lot of time dealing with deviant behavior or setting up materials or transitioning between situations you can’t finish the content planned for the session, you have to act quickly, you have to give more time to student learning and rehearsals, you have to help the students more to overcome their problems; there the exercise for two is still difficult at their level so I have added a student to each workshop it has become accessible”. The teachers used the same regularities of intervention for pedagogical management but at different percentages. The female teacher acts more on the environment and the work climate and she encounters more discipline problems with the students and they sometimes use tricks and twisted and devious ways and empathy sometimes the threat with the note for the mastery of students. On the other hand, the male teacher acts more on the student and his disposition in order to achieve successful learning. The female teacher puts more energy and provides more physical effort than the male teacher for the pedagogical management of the practical sessions in gymnastics.

3.2. Didactic Management According to PE Teacher Gender

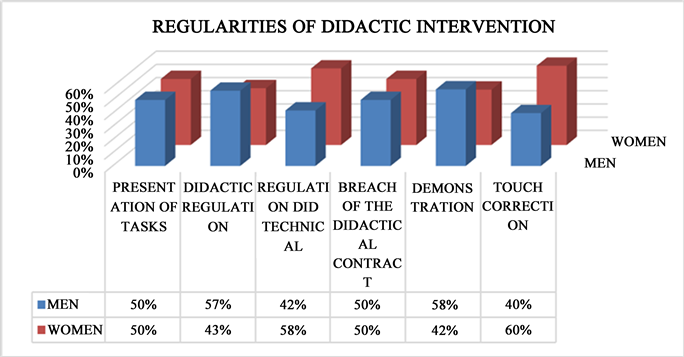

The regularities of teachers’ interventions during the gymnastics sessions for the didactic management, were subjected to the percentages. The results are schematized by the following histogram:

According to Histogram 2, the percentages of presentations and explanations of tasks and the percentages of breaches of the didactic contract are equal for men and women. Male teachers bring more didactic regulations and demonstrate more than female teachers. During the self-confrontation interview, a man commented, “In the beginning, I explain the work required and I even demonstrate it, and then the student is there, I don’t intervene, I’m always there, distance you have to let the student act before intervening, sometimes I change a whole situation to avoid wasting time if the student doesn’t succeed, it’s good I change, I even replace elements with others”. While the women bring more corrections to the technical gestures during the practical sessions than the men and they exploit more the touches to act on the execution of the student in order to bring him concrete modifications. During the self-confrontation interview, a woman replied “the student must perform a sequence at the end of the session. He must get used to linking the elements, I repeat the sequence each session by adding a new element with that and again the student finds the time to make parasitic gestures, like pulling his sweater touching his hair so he must learn to avoid these gestures little by executing a sequence, I insist too much on the beauty of the gesture for the girl, I tell them that for you it’s not like for the boys, you have another aesthetic side, coordination and the beauty of the gesture and not a virile work like the boys based on force. Look there, this girl wants to do the parade for her buddy, she does it badly, the risks breaking her neck, yet

Histogram 2. Regularities of didactic intervention.

I’ve explained it quite a few times, that’s why I prefer to do the parade myself, I make corrections as I go, I approach, especially girls, to avoid accidents, the student must return home safe and sound”. Thus, men and women used the same regularities of didactic interventions during gymnastics sessions. The women act more on the correction of the technical execution of the student on the other hand the men bring more modifications to the learning contents and they correct more by bringing demonstrations of the technical gesture. The female teacher acts more on the student and the male teacher acts above all on the content of knowledge. Men and women act in different ways to achieve the same goal of improving student performance. The female teacher acts more physically during teaching practice. She is more tactile than the male teacher.

3.3. Management of Mobility According to PE Teacher Gender

3.3.1. Didactical Distance vs Gender of PE Teacher

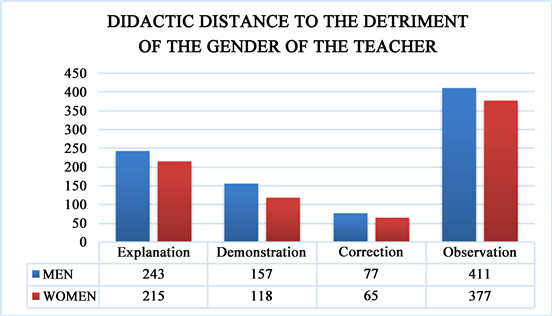

The average distances observed during the practical sessions to the detriment of the gender of the teacher are schematized by the following histogram:

According to Histogram 3, male and female teachers use the same proxemics categorizations during gym sessions. The participants in this experiment place themselves at a great distance from their pupils during the observation of the progress of the work. This distance decreases during the explanation and the demonstration to allow the students to listen well and see the teacher well. This distance decreases again during the correction until having the possibility of correcting the pupil by the physical contact and the touch. A slight difference in the length of the distances which does not exceed 40 centimeters in the placements of the female teachers is noticed, which makes them closer to the students than the men. This can be explained by the affectionate and reassuring nature of the woman. However, teachers, men and women, remain vigilant for the safety of students and especially that of girls except that women remain more awake

Histogram 3. Didactic distance to the detriment of PE teacher gender during practical sessions.

and more sensitive to this safety. During the self-confrontation interview on their placements at the time of viewing the videotape of the practical session, a male teacher commented “You have to be careful with the placement when you work in workshops, I put myself in the gap to see how it goes, good look there, I’m approaching to parry the girls myself for safety”. A female teacher commented “I withdrew to see there and then I moved closer to make this student feel safe, I helped her and she succeeded”.

3.3.2. Teacher Mobility

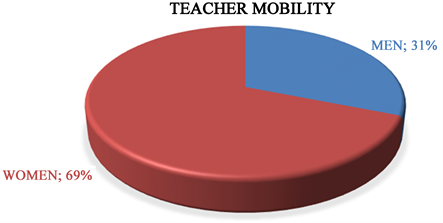

The mobility of the teachers participating in the present study is put in percentages. The results are schematized by the following diagram:

According to Histogram 4, female teachers move during gymnastics sessions more than double the displacements of male teachers. During the self-confrontation interview, a female teacher commented “I come closer to avoid fear and the student feels safe, I help him and he succeeds and my end goal is for the students to work and come home safe and sound, there, look, I’m afraid for these students, there I turned my back on this group then I quickly realized, and I turned to them, for their safety, because they can do everything, you have to expect everyone from the student even if I go away to observe from afar I come back quickly to intervene I circulate from one workshop to another always their safety first, uh, the preventive side accidents, if you like, I’m careful moving between the groups and I put myself closer to the workshop where there is more risk or where the students have not yet managed to learn so for my case this workshop where I placed a rug against the wall”. A male teacher commented “The student is there, he is working, I do not intervene, I am always at a distance, if it is necessary to get closer I intervene closely, but often I place myself far away and I do it on purpose to see how he behaves, being very close is watching him all the time, I approach when the student needs my help when he is not able to perform the exercise correctly, we can direct him even from afar, the student must be allowed to act before intervening”. Thus, women are more dynamic and active during their teaching practice than men. On the other hand, the latter are more distant and much less mobile than the female teachers. This dynamism and this activity cost a lot of physical and mental energy to women teachers.

Histogram 4. Teacher mobility during gymnastics sessions.

3.4. Management of the Teacher’s Simulated Emotions during Gymnastics Session

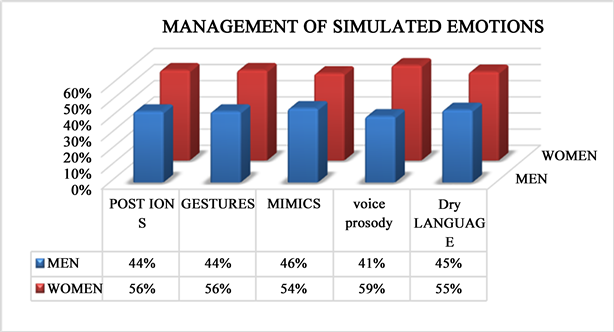

The emotional expressions simulated by the teachers to mark their positions and their opinions vis-à-vis the students, during the gymnastics sessions, were put to the percentages. The results are schematized by the following histogram:

According to Histogram 5, the percentage of body postures marked by women during PE sessions is greater than the percentage marked by men. Women use body language more to influence students than men. As well as the percentage of the use of gestures marked by women to express their positions, during gymnastics sessions, is higher than that of men. Women score the highest percentage for the use of facial expressions than men. The percentage of use of voice prosody during PE sessions by women is in the majority compared to the percentage of men. Women marked the highest percentage for the use of dry languages to communicate their positions to students during PE sessions. In practice, male and female teachers mobilize their emotions for good class management and to encourage the student to invest and improve his performance, but at different percentages. Women play more with his emotions and they put more energy and provide more mental and physical effort in the course of teaching practice to renew the didactic and social contracts in order to succeed in passing on the information. The results according to the percentages of the parameters of management of the emotions of the teachers during the teaching practice reveal that the gender influences the expression of the simulated emotions (posture, mimicry, gesture, language and prosody) and that the women play more of their emotional reactions than men. The testimonies of teachers, of different genres, are taken for this section during the self-confrontation interview. One man commented “I’m making faces and laughing at this student outright out loud to humiliate him maybe scare him just to put him in his place and line you know, it disrupts the session; and it’s contagious such behavior if I don’t

Histogram 5. Percentages of simulated emotions managed according to the gender of the PE teacher.

act immediately as I did there with the deviant students, you have to set limits and call order on the spot if not they won’t stop, the student tries testing the teacher all the time there I pretended to be pissed when I actually wasn’t just to get him back to work you see everyone is calm and working a good lesson for everything the world”. A woman commented “ah there, I pretended that I’m not satisfied with the fact that after a week of vacation, a little breakup, the students lost everything, the week before last we worked the wheel well today there is nothing despite the fact that we used a whole progression. My reaction activated their little brains watch they get to work and suddenly they remember the details of the execution of the wheel in addition to absolute silence what more do I want?”.

4. Discussion

The main results of this study tend to demonstrate that teachers present stable forms that the dynamics of classroom activity can take. Men and women teachers used the same regularities of didactic pedagogical interventions during gymnastics sessions. And they used the same simulated emotional expressions and the same proxemics categorizations. Except that in the deadlines lies the difference. Male and female teachers marked different percentages for the regularities of pedagogical and didactic intervention, emotional and proxemics management. For the pedagogical management of gymnastics sessions, the female teacher acts more on the environment and the work climate and she encounters more problems of discipline with the students. The results of this research do not coincide with the results of previous research by Couchot-Schiex (2007a), which demonstrates that teachers strictly manage student activity, therefore women are found to be more flexible on this point. This research shows that women teachers sometimes use twisted and devious tricks and ways and sometimes empathy, threats with the mark for the mastery of students. The results of the present research for classroom discipline corroborate with the results of Couchot-Schiex (2005), who demonstrated that during PE sessions, student control remains used more by women by adapting means of control inconspicuous and more diverted. Female teachers maintain silence during work and maintain control of the class by approaching or threatening with the grade (sanctions or threats). In this research, the male teacher acts more on the student and his disposition in order to achieve learning success. These results are not in congruence with the results of Couchot-Schiex (2007a), who assert that the grouping distribution says little about the gender of the teacher. For the didactic management of gymnastics sessions, the results show that women act more on the correction of the technical execution of the student, this means that they are more technical. On the other hand, the men in this study make more modifications to the learning content and they correct more by providing demonstrations of the technical gesture. Thus, the female teacher acts more on the student and the male teacher acts above all on the content of knowledge. These results coincide with those of Roux-Perez (2004), for male teachers but not for female teachers. The author underlines that according to men, the ideal profile of the teacher is to master the activity taught and to be a technical expert. While for women the main reasons that lead them to choose this profession are the desire to be a teacher and success in PE. For this study, the results show that teachers, men and women, remain vigilant for the safety of students and especially that of girls except that women remain more awake and more sensitive to this safety. These results are in congruence with the results of Couchot-Schiex (2007a), who affirms that, within the framework of gymnastics, women remain more vigilant concerning the safety and the assistance of the student, which reveals female stereotypes. To note that teachers, without considering their gender, alternate their placements. They approach the students for correction but above all to ensure their safety. There are even those who parade themselves, always for safety reasons, and they move away to observe the whole class. Except that female teachers observe the closest distance to the student and they are more tactile. These findings are consistent with previous research findings by Vinson (2013), who asserts that PE teachers use the same proxemics categorization (social, personal, and intimate distance), and that the use of intimate distance is dominated by the female teacher. While, these results do not coincide with the results of previous research by Boizumault and Cogérino (2010) which demonstrated that touches in PE motivate the student and encourage his participation and investment in the lesson. These authors assert that both the teacher and the teacher exploit touch in similar ways. In practice, the teachers, men and women in this research, mobilize simulated emotions for good class management and to encourage the student to invest and improve his performance, but at different percentages. These results are in congruence with the results of previous research by Boizumault and Cogérino (2012), who asserted that the “staging” or “theatricalization” of the body, through professional gestures that develop into action, turns out to be effective in promoting pedagogical management and learning in PE. To note, too, that women play more with their emotions and they put more energy and provide more mental and physical effort during teaching practice to renew didactic and social contracts in order to succeed in passing the information. The results according to the percentages of the parameters of management of the emotions of the teachers during the teaching practice reveal that the gender influences the expression of the simulated emotions (posture, mimicry, gesture, language and prosody) and that the women play more of their emotional reactions than men. These results corroborate with the results of previous research by some authors such as the results of (Couchot-Schiex, 2005, 2007b) who confirmed that gender affects aspects of verbal and non-verbal communication Couchot-Schiex (2005) and affective climate, women use devious forms and means to control their classes like affectionate relationship or physical closeness. As well as the results of previous research by Vinson (2013) which confirmed that the non-verbal is used by both the male teacher and the female teacher, except that it is not exploited in the same way, the female teacher manipulates the students while the male teacher never or exceptionally uses this manipulation procedure. On the other hand, the results do not coincide with the case of the men in this study.

5. Conclusion

During this research, the results note that teachers present stable forms that the dynamics of classroom activity can take. The male and female teachers used the same regularities of pedagogical and didactic interventions during the gymnastics sessions and they used the same proxemics categorizations during their teaching practice. They also exploited the same emotional expressions to simulate their feelings and influence the student’s performance. The difference lies in the percentages scored by male and female teachers. For the pedagogical management of the practical sessions in gymnastics, the female teacher acts more on the environment and the working climate, on the other hand, the male teacher acts more on the student in order to achieve learning success. During the didactic management of the gymnastics session, the female teacher acts more on the student and the male teacher acts above all on the content of knowledge. For proxemics management during teaching practice, the female teacher moves, during gymnastics sessions, more than twice the displacements of the male teacher. For the management of the emotions of the teacher during the practical sessions of gymnastics, the teacher men and women mobilize their emotions for a good management of class and to encourage the student to invest and improve his performance but, with percentages different. Women play more with their simulated emotions during teaching practice. Thus, the female teacher is more motivating, reassuring, tactile technical, mobile, affective, dynamic and active during the teaching practice than the male teacher. The female teacher puts more energy and provides more physical effort and dissipates more mental energy, during the teaching practice, to renew the didactic and social contracts and to succeed in passing on the information. The gender of the physical education teacher impacts his teaching practice. The female teacher is involved and invests more physically and mentally than the male teacher during the educational intervention.