1. Introduction

If we were to follow the precepts laid out by Charles Rosen in The Classical Style, we would have to consider the works of Haydn—and those of other composers—written before 1780 as stylistically hybrid. In a fitting criticism of Rosen’s hardy dating for the emergence of the Classical style, James Webster insists that the “[supposedly] flawed production before 1781” be assessed in its own right and not be seen as “historiographical explanations of the development of Classical style” (Webster, 1991). That works ought to be seen in their own right and not part of a teleological course is indeed a sound argument. Nevertheless, the gulf that some musicologists see between the String Quartets Op. 20 of 1772 and the Quartets Op. 33 of 1781 has been exaggerated by Rosen, and, to be fair, even by Haydn himself. The set of six keyboard sonatas (Hob. XVI: 21-26, in C, E, F, D, E-flat and A, respectively) written in 1773 for his employer, Prince Nikolaus Esterházy, represent an ideal example against a supposedly ‘amorphous style’ as well as an essential post for Haydn’s writing of this period; and yet it was James Webster, in his just apology for the musical output preceding 1780, who questionably discounted the Esterházy Sonatas’ importance by labeling them as, “lighter in style” (Webster, 2001).

Webster himself has remarked that the problems of style must not be “dependent on crudely reductive applications of the concept of evolution to stylistic development in the arts” (Webster, 1991). Such consideration surely must be afforded to the sonatas of 1773. By looking more closely at these sonatas, I believe the periodization of the Classical style may—and should—be recast. Furthermore, aspects of the Classical tradition itself should also be revisited, since, as we shall see, Rosen’s description is at times debatable. To elucidate issues of periodization and to put forth additional features of the Classical style that might enhance our understanding, I shall focus on a few key movements from the set, for they present a number of outstanding passages that not only challenge their being relegated to the category of hybrid or even minor works, but also display, either in germ or full-bloom, a number of singular melodic, harmonic, structural, and formal devices employed in compositions by later composers. This shall charge Haydn’s Esterházy Sonatas as authentic precursors of peculiar innovations generally associated uniquely with Beethoven, and shall draw fresh attention to their significance.

2. Sonata No. 23 in F Major, Hob. XVI/23

The second movement of the F-major Sonata Hob. XVI: 23 is a Siciliano in the key of F minor with a poignant melodic line over a steady accompaniment in the bass. (The reader is invited to observe the striking similarity of its theme with the second movement of Mozart’s Piano Sonata in F Major, K. 280, written at least a year later, probably in early 17751.) Rosen describes what in his view is the indeterminant nature of the music of this period:

It is the lack of any integrated style, equally valid in all fields, between 1755 and 1775 that makes it tempting to call this period ‘mannerist’. […] The neoclassicism of Gluck, with its willful refusal of so much traditional technique, the arbitrarily impassioned and dramatic modulations and syncopated rhythms of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, the violence of many of the Haydn symphonies […] much of this is the manner that tries to fill the vacuum left by the absence of an integrated style. But so is the sophisticatedly smooth and flat courtly style of Johann Christian Bach; the effect is often chic rather than expressive, and the elegance is chiefly one of surface, as we are always conscious of what is being deliberately renounced for the sake of this grace […] (Rosen, 1971).

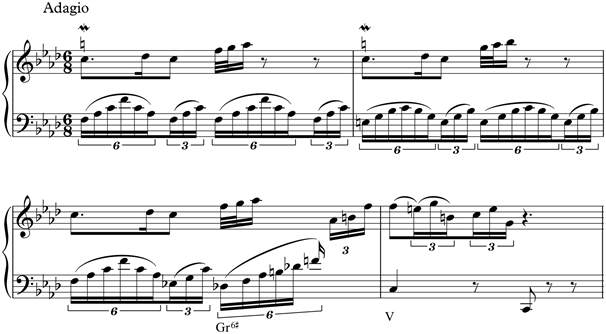

Contrary to Rosen’s pronouncement, the second movement of Sonata No. 23 displays an absence of stylistic uncertainty and slight musical inspiration as well as a pronounced expressivity: this movement’s intense, earnest Stimmung within a balanced phrasal structure is altogether different from Rosen’s description. All such features within this movement—indeed the most striking ones—situate it unequivocally in a new, non-Baroque, non-mannerist canon. The astonishing cadenza over measures 3 - 4 is paradigmatic in this regard as the accompaniment rises from the bass to become the main melodic line. To be sure, Rosen’s own description of an essential feature of the Classical style is this very alternation between accompanimental and thematic material; in fact, Haydn articulates the end of his initial phrase with an arpeggio that begins in the left hand, ascends up to the right, surprisingly becomes melodic, and is then punctuated with a German augmented sixth that gives prominence to the cadence on the dominant as it ends with a rest (Ex. 1(a)). The surprising appearance of such a chromatic chord so early in the movement, markedly arpeggiated in the melody throughout a full beat, clearly draws attention to the ensuing cadence, whose urgency is further highlighted with just a short, low C in the bass and a two-beat rest. This is stylistically antithetical to earlier music, for, as William Rothstein has indicated, “the disguising of cadences through continuous surface motion is a common Baroque characteristic” (Rothstein, 1989). Here, texture, harmony, melody and silence all emphasize the cadence.

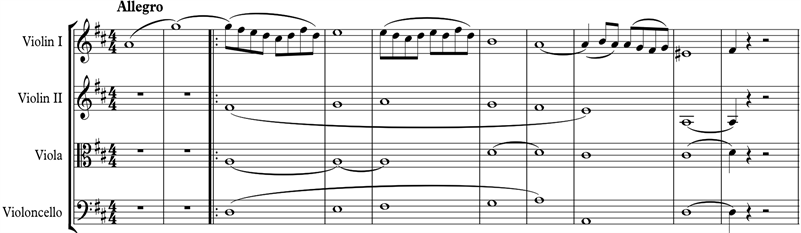

Another principal characteristic of this movement is its vocal temperament: the slurs over the descending cadence and the absence of a slur over the last

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

Ex. 1. (a) Haydn, Sonata No. 23, second mvt., mm. 1 - 4; (b) Haydn, Sonata No. 23, second mvt., mm. 5 - 12; (c) Haydn, Sonata No. 23, second mvt., mm. 18 - 20; (d) Haydn, Sonata No. 23, second mvt., mm. 32 - 39.

triplet (suggesting these notes should be performed with portamento). The sudden appearance of the second theme’s relative A-flat major and the discursive nature of its incipit (mm. 5 - 6) are also typically Classical, as are the repeated A-flats of measures 7 - 8 set over the intensifying harmonic background. After rousing unisons (m. 10), characteristic of a Siciliano, a descending chromatic motion appears in the melody (m. 12). Such unaccompanied, poignant inflections are quintessential operatic conventions, a chief influence on the formation of the Classical style (Ex. 1(b)).

The prominence of this vocal poise found in a number of slow movements of the Esterházy Sonatas is not coincidental. In September 1773 Empress Maria Theresa arrived at Esterháza from Vienna on an official—and grandiose—state visit, and Haydn as Court composer was commissioned to write the opera L’Infedeltà delusa (“Deceit Outwitted”, Hob. 28/5) by Marco Coltellini (1724-1777), of which he was very proud, and at the time regarded as his greatest vocal music composition (Robbins Landon, 1978). In fact, contemporary accounts of the royal visit highlighted the success of L’Infedeltà delusa, mostly in a specially printed brochure in French, which described Maria Theresa’s visit, and in which we read:

[…] les Musiciens du Prince ont eu l’honneur d’exécuter avec beaucoup de succès un Opéra Italien de la composition du Sr. Heyden [sic] Maitre de chapelle; dont les talens sont connus dans toute l’Europe par la composition de plusieurs autres morceaux de Musique […]2 (Robbins Landon, 1978).

For this occasion, Haydn also set Metastasio’s Alcide, for which he had composed an earlier version in 1763; so naturally, operatic and vocal patterns were very much on Haydn’s mind during this period, as is projected throughout in these sonatas. Other sections of this movement betray passages that are instrumental in character as well: the figurations of measure 18 are typical of keyboard writing, while measure 20 has figurations that recall the cello (Ex. 1(c)), which render this stirring Adagio vocal in temperament while instrumental in achievement—a hallmark of the Classical period.

Bipartite form looks toward earlier instrumental forms, but the harmonic design of the second section conforms prophetically to later evolutions. Haydn briefly reiterates the A section’s second theme in the dominant, C minor (mm. 24–26), in order to return to the F-minor tonic by way of a fleeting augmented sixth chord on C major (m. 27). This functions as a structural dominant and is prolonged until measure 32, where a return of section A’s thematic material in the tonic intimates the sensation of recapitulation (Ex. 1(d)). Thus, in the Siciliano Haydn is operating a polarization of the tonic/dominant relationship. This, according to Rosen, and quite correctly I believe, demonstrates another key feature of the Classical style. The impression of recapitulation is further intensified by discovering in section B (mm. 32 - 39) much of the thematic material in the tonic, drawn from section A. These measures, however, are more dramatic than the corresponding passages in section A, both harmonically and melodically; all such aspects evince another influence at play, namely vocal music, and specifically the Aria (A-B-A’) with its customary expansion of earlier material: measures 35 and 37 are intensifications of measures 17 and 12, respectively. In earlier bipartite sonatas—such as Scarlatti’s—B sections usually only exhibit partial material from section Α, that though recognizable, is often not literal and is only evident in the tonic at the very end. And so, this movement is transitional in that it combines earlier formal elements with later thematic and harmonic ones.

In recalling Rosen’s epithet of this period’s music as ‘mannerist’, I should like to asseverate the contrary and insist that at no point is this movement ‘chic rather than expressive’; and the elegance is never ‘one of surface’, nor are we ever ‘conscious of what is being deliberately renounced for the sake of this grace’ as we saw Rosen assert above. What he is suggesting is the Empfindsamkeit that some might associate with a mid-seventeenth-century ‘mannerist’ period and which actually, as the word conveys, is a sentimental vein insufficiently discussed by Rosen. Instead, this movement is a salient illustration of Haydn’s model during these years: guise is indissolubly tied to expression, with supreme clarity of harmonic, rhythmic, and phrasal articulation, all poised for a stirring, even dramatic mien, as we can verily recognize in this Siciliano.

Referring to Haydn’s earliest compositions Rosen fittingly remarked that, “expressive intensity had previously caused Haydn’s rhythm to clot; and rich, intricate phrases had been followed all too often by a disappointingly loose cadence” (Rosen, 1971).

That time had passed.

3. Sonata No. 22 in E Major, Hob. XVI/22

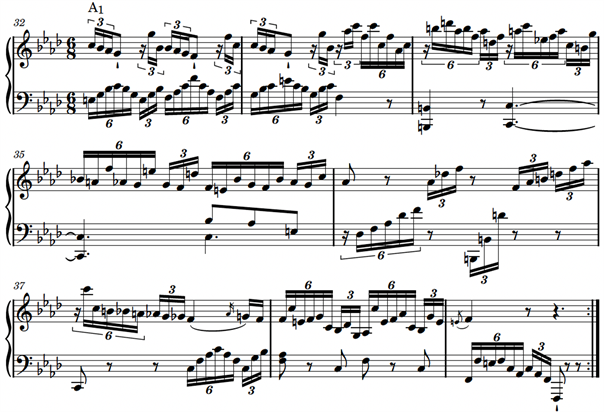

The next passage I shall examine (Ex. 2(a)) is the one in measures 9-12 of the first movement from the Sonata in E major, Hob. XVI: 22.

Here, in what appears to be a second theme, we find a chromatically ascending bass line from D to G. Such a bass—even in this narrow scope—is momentous because its first appearance in a sonata, whether as a harmonic, thematic, sectional, or structural component, has usually been linked to Beethoven: Donald Francis Tovey has posited that, “it is one of the most cogent affairs of dramatic destiny to be found in any music. […] A gradually rising bass produces tension and excitement, if only because it is in the general case of a rising voice […] and I do not know of anything in Haydn or Mozart that seriously anticipates its principle” (Tovey, 1944). Since Tovey’s testimony, theorists have sought earlier examples of a chromatically ascending bass line. Carl Schachter pointed out to me two instances—in Mozart’s E-flat major Piano Concerto, K. 449 (mm. 2293 - 234) and Cherubino’s aria “Voi che sapete” (mm. 53 - 58), in Le Nozze di

(a)

(b)

Ex. 2. (a) Haydn, Sonata No. 22, first mvt., mm. 9 - 12; (b) Haydn, Sonata No. 22, first mvt., m. 53.

Figaro; I have found another keen example leading to the dominant in the Adagio introduction of Mozart’s D-major “Prague” Symphony, K. 504 (mm. 18 - 26).

Haydn’s passage which precedes by over a decade all the above-cited works by Mozart, is homologous to a well-known passage in Beethoven’s Sonata in A major, Op. 2 No. 2 (Ex. 3). In both works, the theme in the right hand is repeated and transposed sequentially, while the bass rises chromatically in the left hand’s accompaniment. Moreover, the rising bass emerges at the same spot in both pieces—a seemingly secondary subject that turns out to be the transition. In both instances, too, the expositions are deeply anchored in the tonic and struggle to move away from it. When they do, a firm rooting of the dominant is delayed; and it is this rising bass that affords the departure from the tonic and arrival at the dominant. In Haydn’s Sonata No. 22, the dominant is promptly reached but remains unstable until a closing theme, revealing a “continuous exposition” that is very common in Haydn. In Beethoven’s Op. 2, No. 2, however, the rising bass is on a much larger scale, with the climbing bass acting as a propulsive force that moves to the dominant, out of the tonic, thus giving the transition’s repeated subject the sensation of a secondary subject. Beethoven’s exciting expedient is due to its dimension: a diatonic ascending bass lasting 11 measures (mm. 58 - 68) precedes the five-measure, chromatic bass rise (mm. 70 - 74) that surges to a V/V medial caesura (Ex. 3). The latter appears late in the exposition and what follows is but a closing theme, revealing that here, too, we are before a continuous exposition, a feature rarely employed by Beethoven. (Haydn’s influence may be at hand here, for the Op. 2 sonatas were dedicated to him.)

Beethoven would later famously stretch a chromatic ascending bass to extreme dramatic consequences in the development of the F-minor Sonata Appassionata, Op. 57. (Another example is the ‘fugato’ passage in the third movement

Ex. 3. Beethoven, Sonata Op. 2 No. 2, first mvt., mm. 58 - 76.

of the Piano Concerto No. 3, Op. 37 in mm. 245 - 255.) Still, despite its smaller compass, Haydn’s procedure in this context represents a significant precedent inasmuch as it escaped even a thorough analyst as Tovey, and is, as far as I know, the first instance of a chromatically-rising bass line arranged structurally. Haydn’s device is clearly relevant to him, since he employs it throughout the movement by various means and in various circumstances: throughout the development Haydn reiterates the chromatic surges in both bass and melody; in the recapitulation we find the same chromatically-rising transition, as expected, a fifth below; and finally, just before beginning the transition in the tonic Haydn further accentuates the process by repeating the very same chromatic rise, D to G, as it first appeared in measures 9 - 12, this time recast melodically and compressed in just one measure (Ex. 2(b)).

4. Sonata No. 24 in D Major, Hob. XVI/24

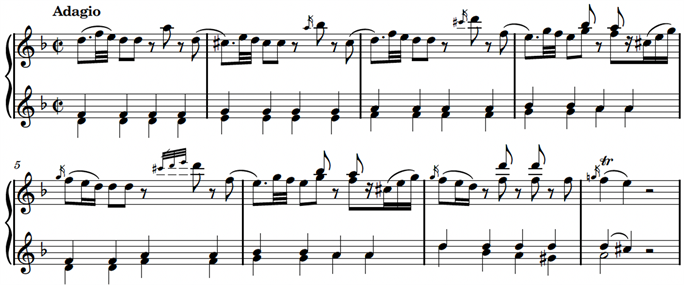

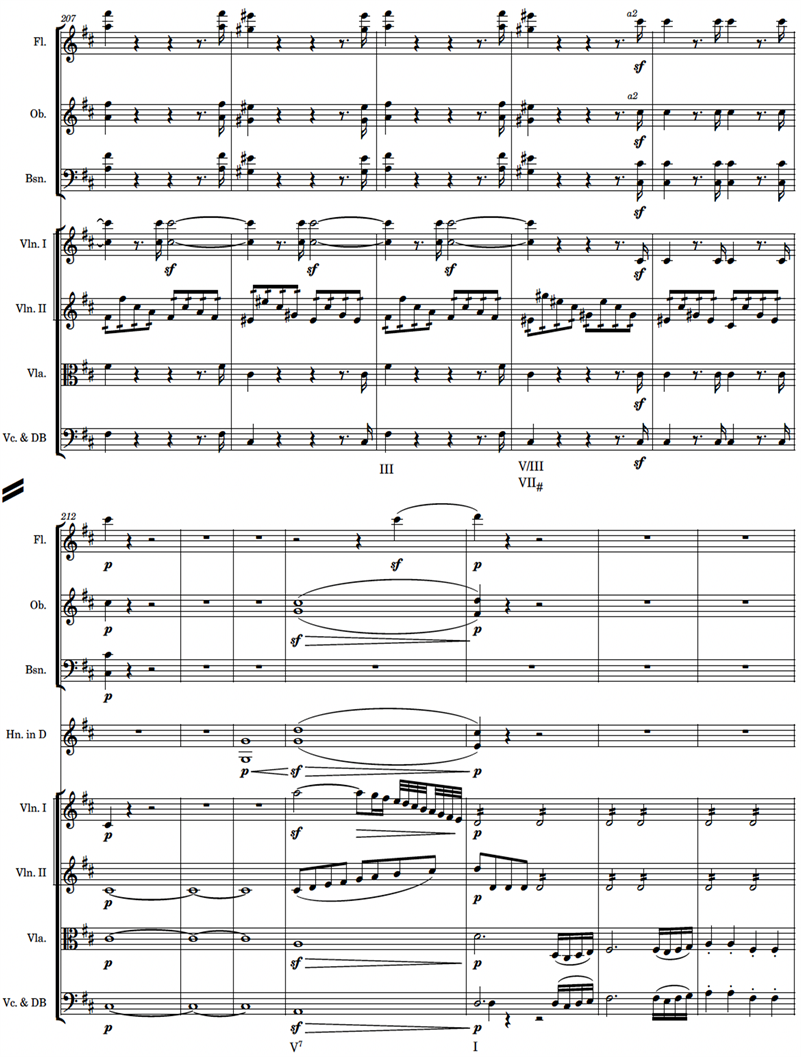

The D-major Sonata Hob. XVI/24 includes a D-minor Adagio, a slow-movement sonata form without development, paradigmatic of Classical sonatas’ middle movements. As the Siciliano of Sonata No. 23, this movement has a decidedly vocal trait; and it, too, is built on a first theme (mm. 1 - 8) that halts conspicuously, without delay, on the dominant (Ex. 4(a)). A considerably longer theme in the key of the relative major (F major) ensues with a lyricism that is perhaps even more pronounced than the Siciliano examined above.

The theme in F major (mm. 9 - 22, Ex. 4(b)) is a melodically developed version of the first theme, which prefigures the monothematicism Haydn employed in so many Sonata-Allegro movements and that was to became a hallmark of Haydnian works. The undulating accompaniment and the F-major theme’s melodic figurations much resemble an aria, which culminates on a high F (m. 21) and ends on a trill on the dominant that leads to a deceptive cadence (m. 22). A two-measure codetta springs from the latter, attenuating the intensity accrued throughout the preceding measures, and ending section A on a full crotchet rest.

But then, the unexpected occurs at the beginning of the recapitulation (m. 25), the most suggestive moment of the entire movement: the main theme moves to G minor (iv) by becoming a dominant seventh with a C-natural appearing in the theme’s second measure over an F-sharp that resolve in the next measure on the same G-minor thematic cell (Ex. 4(c)), driving the doleful mood to an even more pungent extent.

The key of G minor sets in motion a harmonic journey (Ex. 4(d)), which though not remote, is emphasized by a series of dissonances in the accompaniment. Intervals of seconds pierce the first beat of measure 28, are repeated throughout the measure, and are resolved in the following one; then again, minor seconds appear in the first and second beats of measure 30 to be resolved in the third and fourth beats. The impact is further increased in the melody by syncopations, chromatic passages, and a final Neapolitan harmony, which resolves on an applied dominant of V in measure 34 (I6-♭II6-V65/V-V). The concluding dominant lasts for the final three measures in the form of an alternating cadential 6/4, ending the movement on the dominant with a descending arpeggio leading to “[attacca] subito [il]Finale”.

A harmonically shifting retransition theme is unusual and telling in two respects. The first is a matter of musical form that affords an originality to the Esterházy batch which alone would suffice to reverse Rosen’s temporal classifications of the Classical style: anyone would agree that the Classical style is the heyday of sonata form; so a recapitulation’s fluctuating harmony signals a successive stage of that idiom we call ‘sonata’, since such an idiom must already be extant if a change in its harmonic design is to be wielded. (Hence other later examples of ‘unorthodox’ harmonic recapitulations in sonatas by Mozart and Beethoven.4) This is analogous to a Shakespearean sonnet whose structure of three quatrains and one final couplet departs from the original Italian sonnet consisting of two quatrains and two tercets, while keeping the basic framework of 14 verses.

The second implication of a modulating theme in the retransition is a matter of dramatic innovation, for it bears a shift of emphasis on the recapitulation. The dramatic possibilities of a climax in the recapitulation were exploited fully by

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

Ex. 4. (a) Haydn, Sonata No. 24, second mvt., mm. 1 - 8; (b) Haydn, Sonata No. 24, second mvt., mm. 9 - 22; (c) Haydn, Sonata No. 24, second mvt., mm. 25 - 27; (d) Haydn, Sonata No. 24, second mvt., mm. 27 - 37.

Beethoven. (The overcited example of the “Eroica” should suffice, though I would add the almost coeval Piano Concerto N. 4, Op. 58.) Nevertheless, to find Haydn prefiguring such developments is both fascinating, and, concerning his position in music’s history, thought-provoking. (Of course, the hackneyed view of Haydn’s conservatism has long been dispersed.)

5. Sonata No. 25 in E-Flat Major, Hob. XVI/25

Lastly, I should like to turn our attention to the most progressive of the Esterházy sonatas, Sonata No. 25 in E-flat major, Hob. XVI: 25. Paradoxically, it is the only sonata of this set that is comprised of just two movements, yet it is the most radical of the group. In this sonata, Haydn appears to be investigating harmonic valences. We should not forget that during the course of Haydn’s long life, one whose works spanned sixty years, his stylistic and formal evolution traversed the High Baroque into the late Classical era by way of the Rococo; thus, the main genres which he composed—particularly string quartets, symphonies, piano sonatas—reflect his stylistic and emotional evolution, perfectly incarnated by the sonatas of 1773.

The first movement’s exposition has a few formal peculiarities that are indicated in James Hepokoski’s and Warren Darcy’s Elements of Sonata Theory, though they are by far not the most consequential aspects of the Sonata. Nevertheless, the opening Moderato of Sonata No. 25 displays one of the most remarkable harmonic experiments in all of Classical literature by any composer5. At the end of the development (Ex. 5), the key of G minor (III) is prolonged for two measures (mm. 48 - 50), mainly through its dominant D major (VII#). After a firm half-cadence ending with a pause, much like a ‘medial caesura’, we are led to the recapitulation abruptly, directly from the D-major chord, in the following measure (m. 51), thus consigning the pivotal structural passage of development-recapitulation, to the highly unusual harmonic slide to the tonic, VII#-I.

Ex. 5. Haydn, Sonata No. 25, first mvt., mm. 48 - 51.

Haydn’s startling harmonic progression (VII#-I) has been surveyed in Poundie Burstein’s article, Surprising Returns:The VII# in Beethoven’s Op.18,no.3,and Its Antecedents in Haydn (Burstein, 1998). Burstein finds the retransition of Haydn’s Sonata No. 25 to be an antecedent for “the dramatic possibilities of this ungainly harmonic maneuver involving the VII# chord” (Burstein, 1998) employed by Beethoven in his Quartet. Among the antecedents that Burstein lists, is an exhaustive and rather large inventory by Haydn; and in it, this sonata is the very first instance of this remarkable harmonic shift. But let us see how Beethoven wields the VII# chord to lead to the tonic, for doing so shall reveal much about Haydn’s Sonata.

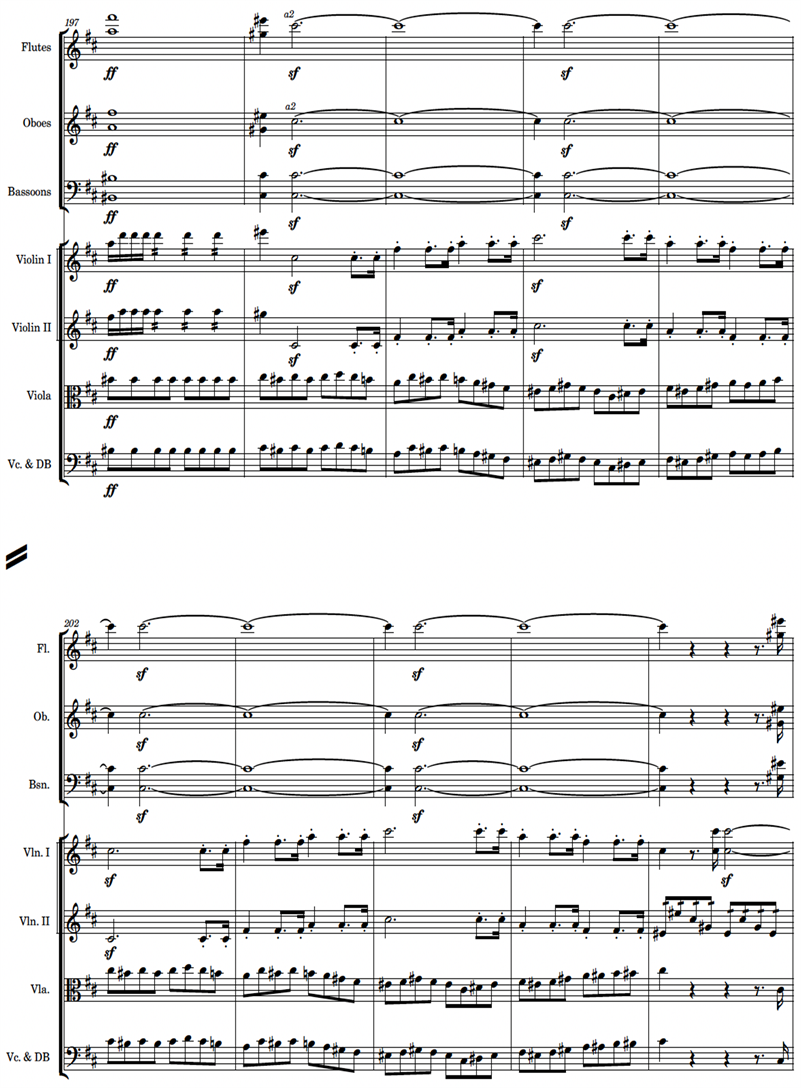

Beethoven’s chief use of the VII# is in two works: the quartet analyzed by Burstein and the Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 36 (1801 - 1802). In both works, we find this ‘ungainly harmonic maneuver’ at the end of the development leading to the recapitulation. In Beethoven’s Quartet (Ex. 6(a)) the VII# chord,

(a)

(b)

Ex. 6. (a) Beethoven, String Quartet Op. 18, No. 3, first mvt., mm. 150 - 169; (b) Beethoven, String Quartet Op. 18, No. 3, first mvt., mm. 1 - 10.

locally, is really a V/III, the dominant (C-sharp major) of the mediant (F-sharp minor), that is reached through an augmented 6th (m. 151) and extends on a fortissimo for 6 measures (mm. 152 - 158) only to dissipate, leaving the root of the chord, a C-sharp in the bass that, having served in a mediant capacity as the V6 at mm. 160 - 161, then acts as the leading tone to D for the return of the recapitulation (m. 160).

Unlike Haydn’s sonata, Beethoven’s return to the tonic is not curt. This is over two main circumstances: firstly, as is evident from Ex. 6(a), the C-sharp-major chord has vanished, leaving us with just a unison piano C-sharp in both the cello and viola for two full measures, and at best, with only the memory of the chord; but the second and more salient reason for the gentle homecoming is that the first theme of the exposition does not begin on the tonic, but rather, on the dominant as a melodic V7 leap (A-G) that reaches the tonic in measure 3, and only resolves fully at the end of the phrase in measure 10 (Ex. 6(b)).

Beethoven employed this exact progression once more in his Symphony No. 2, Op. 36, with as much emphasis (the same ff dynamics) and in the very same spot—the end of the development. This alone is revelatory about the apparent influence of Haydn’s 25th Sonata. In fact, under the caption, “a case for influence”, Burstein states:

It seems likely that the gesture at the end of the development in Beethoven’s Op. 18, No. 3 was inspired by Haydn. After all, the use of a VII# at the end of a development seems too unusual to be accidental. This odd harmonic twist can hardly be considered a standard part of the musical language of the time. After a long search, I have only been able to find three pieces by other eighteenth century composers that use this strategy, including only two by Mozart (the finales of his Piano Concertos K450 in E♭ major [sic6] and K451 in D major, both written in March 1784) and one by the obscure composer Friedrich Witt (the last movement of his Symphony No. 2 in D major).

There is no documentary evidence confirming whether or not Beethoven knew any of the pieces cited in Table 1. [Burstein is referring to a list he compiled of Haydn’s pieces with the use of the VII# chord.] Nevertheless, it would be hard to believe that he was unfamiliar with any of them (Burstein, 1998).

At the end of the development of Beethoven’s D-major Symphony (Ex. 7), we find the mediant key of F-sharp minor lasting fourteen measures (mm. 198 - 211). Again, this is prolonged mostly through its dominant, C-sharp major (VII# chord). The timbre of C-sharp (7^) is obviously accentuated, for it is extended in the flutes at the very top of the stave for eight measures (mm. 198 - 205), and in the last measures of the development, it is additionally laid firmly in the bass on a VII# chord that once again disbands leaving just the C-sharp in the bass—contrabass, violoncellos, violas, second violins—for three full measures (212 - 214) before the recapitulation begins at measure 216. Yet, unlike Quartet Op. 18 No. 3, the first theme of the Symphony is anchored in the tonic, which outlines a D-major triad; and thus here Beethoven adds an A in the bass to form a pronounced dominant-V7 througout the very last measure of the development (m. 215) in order to usher in the recapitulation. Interestingly, the A is heralded by the horn in the previous measure, right as the solitary C-sharp in being prolonged in the bass.

And so, in his uses of the VII# chord for approaching the important structural site of the recapitulation, the dominant is never omitted by Beethoven, for the dominant is either part of the first theme, as the Quartet, or as in the Symphony, it is imposed as its polar opposite in the measure immediately preceding the arrival of the first theme in the tonic.

This is not the case with Haydn’s Sonata No. 25. As we have seen, the recapitulation and the first theme and the tonic are preceded by a VII# chord followed by a stark pause, whose effect is indeed brusque.

A theoretical assessment is necessary here: the chord I have been labeling as VII# has been identified by some theorists actually as a V/III, an understandable and legitimate determination. Nevertheless, we ought to be discerning and judge each case as it occurs. In the passages we observed by Beethoven, we found the harmony at the end of the development anchored on the mediant. Thus, while the latter harmony was substantially extended and resting under distinct thematic material, the chord at the end of the mediant had the specific effect of a half-cadence on the dominant (V/III, in fact). In Haydn’s Sonata, however, we hear as the primary harmony a D-chord, since the bass is really on D, impelled by a constant shift between C-sharp and D; the mediant (G minor) is therefore not prolonged nor sustained by thematic material, but is rather just the continuation of the circle of fifths occurring throughout the development. Thus, when the development ends on a D-chord followed by a pause, and, eventually, followed by the abrupt emergence of the E-flat tonic of the recapitulation7, the sensation is indeed that of a VII# chord rather than a V/III. Here, perceiving this

Ex. 7. Beethoven, Symphony No. 2, Op. 36, first mvt., mm. 197 - 218.

chord as a VII# is not only seemly, but also indicates Haydn’s clear intention for testing a precise harmonic progression: the notion behind the sequence, or slide, VII#-I rests upon the principle that the leading tone is the fulcrum of the dominant-tonic resolution, and that its presence (as the root of the VII# chord) alone can support this odd harmonic succession. This is the inference Haydn and Beethoven have of it. Hence, in his test with this progression, Beethoven prolongs the root of the chord (7^), or the leading tone of the succeeding tonic (1^), by adding a 5^ in the bass and transforming the VII# chord (or V/III) into a V7 chord: “Beethoven shows that he, like Haydn, was willing to grapple with a seemingly intractable tonal scheme and struggle to work it into the logical foundations of a composition.” (Burstein, 1998).

Burstein, however, does not stress the audacity of Haydn with respect to Beethoven. In fact, Beethoven, to whom one would surely not associate compositional timidity, always dilutes the jarring impact of the VII#-I progression with an added V7, so that the ‘ungainly harmonic maneuver’ of a direct VII#-I is omitted: Beethoven’s progression is actually VII#-V7-I, or quite rightly understood in the quartet and the symphony as, V/III-V7-I.

Haydn’s utilization is more radical. Burstein states that an actual V chord is implied during the pause in measure 50 in order to conciliate the unceremonious return to the tonic. But such suggestion is untenable on various accounts: firstly, there is no hint whatsoever of a dominant; secondly, the leading tone or the bass of the VII# chord is not in the least extended by Haydn; thirdly, the prolongation of the mediant that precedes it with demisemiquavers and semiquavers culminates on a half-cadence with the VII# chord on a whole-beat crotchet; fourthly, a whole-beat pause follows the chord, further causing a startling impact at the reappearance of the tonic at the recapitulation. Due to the oddity of this concatenation, it is impossible for the ear to fill in an intermediate V7 by itself in an undeniable VII#-I progression. With the insertion of the dominant after the VII# chord, Beethoven’s treatment of the progression is lenient, whereas Haydn’s is uncompromising; his experimental vein is more pronounced, and, the transition, sharp. As to the successfulness of the result, it is for the listener to decide, but the experiment remains a bold one indeed.

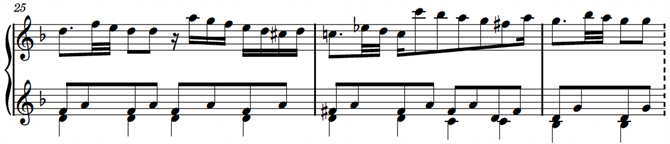

The second movement of this Sonata exhibits a somewhat more relaxing—but no less original—instance of Haydn’s formal quests. This short movement is a canon at the octave in sonata form: exposition, mm. 1 - 14; development, mm. 15 - 25; recapitulation, mm. 26 - 44. The result of this combination is noteworthy: the amalgamation of canon in sonata form is, as far as I can think, unique, and, in the case of this movement, it is pertinent to evoke Bertram Jessup’s indispensable concepts of “intensive aesthetic size” versus “extensive aesthetic size” (Jessup, 1950). The second movement of the A-major Sonata Hob. XVI: 26 displays this intensive compositional vein most, for it is a Minuet and Trio “al Rovescio” (that is, to be played backward from the end, as well as from the beginning).

The appropriation of the ‘old’ contrapuntal tradition was an essential step in the Classical period, one with which Mozart and Beethoven struggled to succeed to integrate into their works successfully; and one can well speculate that Haydn’s delicate, deliciously ear-teasing minuet might have inspired the grander, more explosive fugal offerings of Mozart and Beethoven as they assembled sonata form with the marrow of fugues and canons. The latter are not easily incorporated in sonata form (Beethoven’s Sonatas Op. 101, 106, 110 are also, in part, formidably different solutions to this problem), yet the return of contrapuntal techniques, has fittingly been indicated by the noted musicologist and pedagogue Elvidio Surian as another fundamental characteristic of the Classical style:

The ground on which the musical language of classicism germinates is the ‘gallant style’ based on communicative immediacy. New, however, is the tendency to consider musical construction as something more than just an accompanied melody, but as a dialogue among 2 or more sections, having its own internal coherence that imbues musical speech in all its components (texture, melody, rhythm, harmony, phrase structure). […] The revival of contrapuntal techniques with its standard of parity in the various voices of the polyphonic fabric […] indicates the overcoming of the melodic/harmonic dualism and the possibility of enhancing the compositional structure through variation techniques and the motivic-thematic expansion applied to all parts (Surian, 1991)8.

In other words, the reintroduction of contrapuntal procedures nourished the maturation of later styles, for it sanctioned the principle of developing variation9 in all the parts.

6. Conclusion

The task of this paper has been to reassess the Esterházy Sonatas, and in so doing, (re)establish their deserved merit and move them out of their relative oblivion. The two-fold drawback evinced by this essay has, I should hope, been settled. Firstly, I feel a secure stand has been made with regard to Webster’s assessment that the sonatas of 1773 are slight in inspiration and in content; Haydn’s numerous feats in these works—ranging from radical innovations to expressive verve—demonstrate the contrary. (From this point of view, the artistic relevance of these sonatas is divested from the question of style.) Secondly, the question of placement of ‘Classical style’ ought to be reformulated. I would argue, as Elaine Sisman did in a conversation with me, that though Rosen’s description of its features is thorough enough, his periodization is faulty; she proposed that the beginning of Classical style be placed well before Rosen’s delimitation of 1780; I would propose c.1770. This would comprise works as the Esterházy Sonatas in addition to works such as the Farewell Symphony, an argument Webster has justly implied, when, speaking of Symphony No. 45, he stated that, “many aspects of Haydn’s music can be appreciated only by ignoring the concept of ‘Classical style’” (Webster, 2001).

Arguments of style are restless, protean, yet always fascinating and fecund. For example, contrary to Rosen’s judgement, we may view the six Quartets Op. 20 (1772) as already Classical, despite, or, because of their fugues in the finales of Quartets 2, 4 & 6; therefore, although these fugato finales are Rosen’s main argument against Op. 20 belonging to the Classical style, Webster’s discernment is diametrically opposed10. In fact, the integration of fugue and sonata form (and also in sonata form, such as the transition of the exposition of the last movement of Mozart’s Symphony K. 551 or the development of Beethoven’s finale of Sonata Op. 101) is viewed by both Webster and Surian as an achievement of the Classical period, expressly found in some of Mozart’s and Beethoven’s most assertive masterworks.

The Esterházy Sonatas are thus an important step between the Quartets Op. 20 and the ‘revolutionary’ ones of Op. 33. Of course, we ought to keep in mind the implications in considering different genres. William Rothstein’s words in this regard are revealing: “The differences between these subspecies [genres] are overshadowed by the larger compositional intelligence that informs all.” (Rothstein, 1989). The inconsistency among genres is highlighted by Rothstein with even more catching words when he noted that, “This [musical genres] is a complex issue and one that can only be addressed here in a very cursory way. At different periods of Haydn’s career, the various instrumental genres in which he composed differed from each other by varying degrees. In the period before 1766, for example, there are obvious differences in phrase rhythm between Haydn’s keyboard sonatas and his divertimenti for string quartet, and between both of these genres and the symphony. By and large, the differences diminish over time. By 1785 there is relatively little difference in phrase rhythm between a Haydn symphony and a Haydn string quartet. But in the 1790s, however, the differences increase again: as in the years 1766-72, the string quartet becomes more adventurous than the symphony (though not to the same degree as before) while the piano sonata and piano trio become more relaxed and improvisatory than other genres.” (Rothstein, 1989).

In conclusion, with the Esterházy Sonatas we experience the advance of Haydn’s third (of five) creative periods, as he continues to evolve into the mature, senior master of the simultaneously fluctuating and evolving Classical style. The Sonatas of 1773 exhibit lessons drawn from Op. 20 as well as Op. 17 and Op. 9 (1772, 1771, 1770, respectively) and reveal Haydn’s experimental vein perspicuously, for in these string quartets it is concealed in the polite exterior of ‘society music’, while the less ‘officious’ guise of the keyboard sonata admits exploration forthrightly. The Esterházy Sonatas, as much as the more famous string quartets of 1772 and 1781, disclose Haydn’s genius for incorporating the ‘old’ into the veritably ‘new’. That same genius, best described by Kant, invests consequence to Haydn’s Esterházy Sonatas: “Genius is the talent (natural endowment) which gives the rule to art11.” (Kant, 2007).

Acknowledgements

I should like to thank Paul-André Bempéchat and Michael Linton for their advice, guidance, encouragement, and above all, friendship. I am also grateful to our esteemed colleagues Jonathan Bellman, Simon Keefe, and Denis McCaldin for their valuable insights.

NOTES

1The entire set of the Esterházy Sonatas was printed in Vienna by Kurzbock in 1774, and likely to have circulated in Salzburg, for we have evidence of their appearance soon after in Paris, London, and Amsterdam. See ‘Introduction’ in (Hinton, 1995).

2[…] the Prince’s musicians had the honor of performing, with much success, an Italian opera composed by Mr. Hayden [sic], the Kapellmeister, whose talents are known throughout Europe for the composition of several other pieces of music […] (My translation.)

3The prolonged B-flat starts on measure 219.

4Mozart’s Sonata in C major, K. 545 (1788) and Beethoven’s Sonata in F major, Op. 10 N. 2 (1796-8).

5See Hepokoski & Darcy, 2006, pp. 105, 137 & 177.

6The concerto is in B-flat major.

7In fact, we can read the base as a chromatic ascent: C-sharp/D/E-flat.

8“Il terreno su cui germina il linguaggio musicale del classicismo è lo ‘stile galante’ fondato sull’immediatezza comunicativa. Nuova però è la tendenza a considerare la costruzione musicale come qualcosa di più di una semplice melodia accompagnata, bensì come un discorso tra 2 o più parti, dotato di una propria coerenza interna che investe il linguaggio musicale in tutte le sue componenti (tessuto sonoro, melodia, ritmo, armonia, struttura delle frasi e dei periodi.) […] Il ripristino della scrittura contrappuntistica col suo ideale di eguaglianza tra le voci del tessuto polifonico […] significa il superamento del dualismo melodi-armonia e la possibilità di arricchire la struttura compositiva mediante la tecnica della variazione e dell’elaborazione motivico-tematica applicata a tutte le parti”. (My translation, p. 503.)

9See Walter Frisch. Brahms and the Principle of Developing Variation. (Berkley: University of California Press, 1984).

10See (Rosen, 1971: p. 119) and (Webster, 1991: pp. 294-300).

11§46 “Genie ist das Talent (Naturgabe), welches der Kunst die Regel gibt.”