Effects of Mandating Audits for Egyptian SMEs on Their Financing Opportunities-Analyzing the Egyptian SMEs Audit Market ()

1. Introduction

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are the cornerstone of a strong economy and create jobs for millions. Their capacity for innovation and their ability to adapt to a continuously changing business environment makes them a critical building block for economic prosperity. SMEs are essential in Egypt, which has long been the largest SME hub in the MENA region (the Middle East and Northern Africa).

Lending from banks is the most common source of external finance for many entrepreneurs and SMEs, which are often heavily reliant on straight debt to fulfill their start-up, investment needs, and cash flow. While small projects commonly use it, traditional bank finance poses challenges to SMEs and may be inappropriate at specific stages in the firm life cycle (OECD, 2015).

Egypt’s SMEs face many challenges despite their substantial economic value, including poor financing options. The shortage of access to appropriate financial products hinders the growth and expansion of SMEs. Only about 50% of all SMEs have a banking relationship, and only 20% have access to credit (GIZ, 2021). Securing formal financing often requires SMEs to undergo lengthy and tedious procedures, causing many to go for informal funding channels—i.e., borrowing from relatives or friends. The decision to grant credit for SMEs is affected by the information asymmetry between the SME demanding credit and the bank granting the credit; because available information about those SMEs is often unreliable due to not being audited. Most banks are at risk towards SMEs as there is a lack of data about their credit history, business transactions, financial performance with no official documents to trace. Hence, banks depend much on credit employees’ efficiency and experience for enterprises assessment in the lending process (Boushnak et al., 2018).

The non-availability of financial information is partly due to the lack of owners’/managers’ awareness of the importance of the accounting and auditing functions and the resulting information. Also, many countries exempted SMEs from auditing their financial statements to ease the burden on these entities without regard to the benefits of preparing and auditing financial statements (e.g., Shen et al., 2009; Zambaldi et al., 2011; Saleh, 2017).

The originality/value of this paper, as the authors know, is considered one of the first studies to study, analyze, and test the expected effects of mandatory audits for the Egyptian SMEs on their financing opportunities besides its’ impact on the bank officers’ credit-granting decisions. Also, this paper took a deep look at the Egyptian SMEs auditing market to represent the whole story from both sides, supply, and demand, hopefully helping future researchers in that area.

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. The Evolution of the Egyptian Definition for SMEs

Till recently, before the new Micro, Small, and Medium-sized Enterprises Law (MSMEs law—Law no. 152 for 2020), there was no unified definition for SMEs in Egypt. That is why SMEs were suffering from finance which was an essential factor that may explain the low rates of access to finance. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2018), before the new MSMEs Law, there were three definitions, and each institution applies a different definition as follows:

1) The Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics (CAPMAS) is the primary statistical arm of the Egyptian government. It defines SMEs based on the number of employees; hence micro-enterprises employing less than 5 workers, small firms employing between 5 and 49 workers, medium firms employing between 50 and 99 workers, and large firms with 100 workers or more (Loewe et al., 2013; Rashed & Sieverding, 2014; OECD, 2018; Mona & Irene, 2021).

2) The Egyptian Small Enterprise Law No. 141 of 2004, called the Small Enterprise Development Law, provides the legal framework for such projects. It defines SMEs by several criteria, such as the number of workers, capital size, or a combination of the two criteria. For example, a small enterprise is each enterprise engaged in an economic activity whose paid capital is not less than 50,000 EGP and not more than one million EGP and employs no more than 50 workers (OECD, 2018; Mansour et al., 2019).

3) The Central Bank of Egypt (CBE) defined small enterprises with annual sales between 1 million and 50 million EGP and medium enterprises between 50 million and 200 million EGP. The CBE definition for SMEs also includes the number of employees, yet the latter is only indicative and should not use as the binding definition for SMEs.

Recently, in 2020, as part of the state’s efforts to encourage the Egyptian economy, the Egyptian President issued Law No. 152 for 2020 regarding the development of the MSMEs. The law repeals the previously enacted Law No. 141 for 2004 regulating the same subject matter. According to the new law, the definitions of MSMEs Projects are as follows (Youssry, 2020):

1) Micro enterprises: Each enterprise has an annual business volume or an annual turnover of less than 1 million EGP or every newly established enterprise whose paid-up capital or invested capital is less than 50 thousand EGP.

2) Small enterprises: Each enterprise has an annual business volume or an annual turnover of 1 million EGP and less than 50 million EGP, or every newly established industrial project with paid-up capital or invested capital between 50 thousand EGP and less than 5 million EGP. Alternatively, every newly established non-industrial project with paid-up capital or invested capital, between 50 thousand EGP and less than 3 million EGP.

3) Medium-sized enterprises: Every enterprise with an annual business volume or an annual turnover of 50 million EGP and not exceeding 200 million EGP, or every newly established industrial project which has paid-up capital or invested capital according to conditions of 5 million EGP and does not exceed 15 million EGP or every newly non-industrial project incorporation paid-up capital or the invested capital of which, according to the circumstances, is 3 million EGP and does not exceed 5 million EGP. The Egyptian MSMEs Definitions in Egypt According to Law No. 152 for 2020 can be summarized as follows in Table 1.

![]()

Table 1. MSMEs definitions in Egypt according to Law No. 152 for 2020.

Source: Made by authors.

In the context of the semi-structured interviews/phone calls, by a phone call with Mr. Gharib Hindawi—a board member of the Federation of Egyptian Economic Development Associations and who participated in drafting the Egyptian MSME law. He explained that the new law relied only on capital criteria to classify enterprises into micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises. This classing is inaccurate enough, unlike many countries that depend on several additional criteria as the number of employees. The reliance only on the capital criterion may avoid inconsistency and duplication in defining enterprises, which was already in place before applying this law.

2.2. Egyptian SMEs’ Auditing Market and Public Interest

Egyptian public interest in SMEs’ auditing is less than the European, which studied and determined the critical factors of maximizing the usefulness of SMEs audits. Moreover, accounting practices operating in the Egyptian SMEs’ audit market face significant challenges; they must achieve sustainable financial results with audit service revenues that exceed the total cost of delivering high-quality audit services. Cost-cutting directly reflected in the quality of the services performed is not sustainable (John & Kalina, 2016).

IFAC identifies two public interest considerations regarding the applicability and relevance of international standards on Auditing (ISAs) to the audits of SMEs (UNCTAD, 2016):

• The first consideration is the importance of having an audit of financial statements associated with one consistent level of assurance, regardless of the size of the entity audited or the firm’s size performing the audit.

• The second consideration is SMEs’ assurance needs, on a benefits and costs basis, and whether an audit, an assurance service other than an audit, or no assurance is required.

Results from UNCTAD’s questionnaire show that 22 out of 39 respondents (56%) indicated that SMEs were required to have their financial statements audited. While only two countries modified their answers as follows.

• No audit is required if the entity is not a public interest entity (Lithuania).

• The United States responded that there is no mandatory audit requirement for non-public company financial statements. The decision to audit those financial statements is based on the reporting entity’s circumstances.

According to Saleh, S. (2017), one of the most critical and dangerous limitations facing the development process of Egyptian SMEs is the lack of basic skills related to accounting and records management, and owners are poorly educated and think that accounting is infeasible. Even if financial information is available, a lack of accounting expertise will make it difficult to use, and SMEs’ owners will not adopt appropriate information systems to make informed decisions.

In Egypt, the relationship between SME owners and audit firms is limited to non-assurance services only if necessary when dealing with other parties such as banks. Moreover, they are limited to requesting what is needed to perform tax affairs or obtaining the licenses required for activities, preparing for feasibility studies, and tax advice. In Egypt, the importance of Egyptian auditing standards in regulating auditors’ duties for the SMEs sector is unknown. However, these standards contain principles and guidelines that can apply to any company, regardless of size or legal form, the structure of ownership and governance, or the nature of its activities (e.g., Nagwa, 2020; Mohamed, 2020; Mohsen, 2019; Shaimaa, 2016).

In 2008, the Egyptian Minister of Investment issued Ministerial Resolution No. 166, including auditing standard no. 1005 entitled “Egyptian Guidance No. 1005 Special Considerations for Auditing Small Enterprises”, this guidance aims to describe the common characteristics in small enterprises and explain how they affect the application of Egyptian auditing standards. Haney, E. and Hanan, A. (2014) aimed to investigate and analyze the efforts of the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) in SMEs accounting development, whether about developing the conceptual framework or standards that govern the accounting practices of SMEs. The study has shown that the obligation to maintain regular accounting for SMEs has disappeared. There is a lack of tax and accounting awareness among Egyptian accountants and auditors, especially those dealing with SMEs. Shaimaa, E. (2016) also considered measuring the impact of applying Egyptian auditing standards on SMEs auditing. She concluded a lack of accounting and tax awareness among SMEs owners due to the lack of a conceptual framework for accounting and auditing. Bahaa, E. (2018) also addressed the determinants of the application of SMEs auditing standards in Egypt and applied these determinants by investigating the auditing issues facing SMEs in Egypt and any barriers. The study found a statistically significant association between using the guidelines contained in the Egyptian SMEs Auditing Standard (1005) and the quality of the Egyptian SMEs auditing process when applied. Mohamed E., et al. (2018) aimed to verify the degree of compliance of Nilex-listed SMEs with accounting disclosure requirements. The study concluded that there is no obligation on the part of SMEs within the accounting disclosure requirements contained in the Standard for SMEs. Ebrahim, A., et al. (2019) also aimed to analyze the content of the “2015” Egyptian Accounting Standards for SMEs and compare them with the Egyptian Accounting Standards. The study concludes that the Egyptian Accounting Standard for SMEs “2015” has less recognition, evaluation, and disclosure requirements than the Egyptian Accounting Standard and may apply to SMEs. Abd El Nasser M. (2019) also addressed the importance of external auditing on the reliability of financial statements issued by Egyptian SMEs. He concluded that managers/owners and auditors have a shared curiosity to reduce audit risk and emphasized the importance of developing the right costing system components for SMEs. Ahmed H. (2013) tested the awareness of financial managers and auditors of the considerations related to auditing SMEs when applying the Egyptian auditing standards compatible with international auditing standards. The study showed that auditors in Egypt indicate in their reports that auditing SMEs carried out considering the enriching auditing standards and the laws in force. Also, the study confirmed that Egyptian auditors are more aware of the considerations related to SMEs’ audits and proved a significant difference between financial managers and auditors regarding the terms of the Consultancy services other than auditing.

Egyptian SMEs minimize records and hold some invoices and important documents; this leads to a double burden on auditors to obtain the required information. In the context of the semi-structured interviews/phone calls, within a semi-structured interview with Mohamed Mortada Khalil, a former undersecretary of the Egyptian Central Auditing Organization and a current auditor authorized to audit SMEs explained that the Egyptian audit market is full of irregularities. He added that some companies might prepare multiple budgets for different purposes. For example, SMEs seeking loans ask external accountants to prepare a balance sheet that inflates profits to gain the bank’s confidence in their financial solvency. On the other hand, in the case of taxes, it presents another balance sheet with low profit to avoid taxes.

2.3. Mandatory Audits

A mandatory/statutory audit is a legally required review of the accuracy of a company’s or government’s financial statements and records. The purpose of a mandatory/statutory audit is to determine whether an organization provides a fair and accurate representation of its financial position by examining information such as bank balances, bookkeeping records, and financial transactions (Investopedia, 2020).

Some literature finds that regulation is quite positive and necessary for the audit profession to thrive. In contrast, others state that the research demonstrates that regulation is not favored and is quite constricting. The conclusion’s strength also varies; some come to a firm conclusion, whereas other literature sources state that the findings are not conclusive as there is room for improvements.

The literature that found the regulation to be positive is Vinten (1999), Eldaly and Abdul-Kader (2018), and Quick et al. (2008). Vinten (1999) and Quick et al. (2008) agree that introducing regulatory bodies and independent regulation improved transparency and effectiveness. Eldaly and Abdul-Kader (2018) came to a firm conclusion and found that three strategies would improve auditing in the UK. These three strategies were increased transparency, which would allow the public more access to audit information, an improved quality so that audits become higher efficient, and a reduction in entry barriers, which would allow for more firms to enter the market.

On the other hand, Dewing and Russell (2002) and Dewing and Russell (1997) concluded that regulation did not always create positive outcomes. Dewing and Russell (1997) stated that regulation might be sufficient and carry out its intended use. However, excessive regulation can create a negative public perception and lead the public to believe that auditors are not self-sufficient enough to be ethical without regulation. That means that Dewing and Russell (1997) found too much regulation to be negative. Dewing and Russell (2002) support the notion of disagreeing with regulation. That was due to the research involving participants in the auditing profession who stated that they felt they could be independent in governing themselves and preferred weaker regulation methods, such as non-statutory bodies.

In the literature of mandatory audits for SMEs, we can find studies that indicate that it is preferred to mandate SMEs’ audits. For example, the European Federation of Accountants and Auditors for SMEs (EFAA) noted that European Commission (EC) and national regulators might have gone too far in exempting SMEs from having an audit and raising thresholds as part of reducing the regulatory burden on SMEs. Also, it recommended that regulators reassess the existence and extent of audit thresholds given potential risks to the economy and the public interest. The setting of thresholds deserves a thorough and robust evaluation of SMEs’ audits’ costs and benefits (EFAA, 2019). Hanh and Anh (2020) research results suggested that Vietnam Government should make a mandatory audit of SMEs’ financial statements rather than make it an option for SMEs. Also, they recommended auditing firms actively take their audit services to SMEs rather than wait for their managers to contact them for their services. In their study, Haw I.-M., et al. (2008) examined the effect of mandated interim audits. They reported that voluntarily audited firms’ earnings response coefficients (ERCs) are more significant than mandatorily audited firms. That suggests that investors perceive voluntary audits to be more informative than audits required by the regulators. Cautious is critical of such an interpretation; however, the effect of mandatory audits may be attributable to the firm-specific economic circumstances underlying mandated audits. Lennox and Pittman (2011) indicated that requiring independent audits is a vital policy mechanism accessible to governments to regulate the supply of reliable information to investors. Also, a study for ICF & BMG (2017) aimed to assess the scale of take-up of audit exemptions. This study compared companies eligible for audit exemptions before changing the eligibility criteria in 2012 and those eligible because of those changes. These findings suggest that larger companies may be less likely to take up audit exemptions if this option is only likely to be available in the short term.

Finally, from previous literature, we can admit that information is a public good, and there is a concern that companies would supply a little under private contracting. According to this market failure argument, the authorities should compel enterprises to audit their financial statements to ensure that outsiders access reliable information. In the other aspect, requiring audits suppresses the signal when companies exercise discretion in choosing whether to be audited (e.g., Watts, 1977; Chow, 1982; Melumad & Thoman, 1990; Sunder, 2003). For several reasons, the researchers stress that the research cannot provide a definitive answer to policymakers on whether audits should be mandatory or voluntary.

2.4. Theory behind Obliteration of Mandatory Audits for SMEs

The rationale behind regulators imposing mandatory/statutory audits is that companies have insufficient private incentives to provide reliable financial information voluntarily. Therefore, mandatory/statutory auditing may be socially optimal. The theory implies that information underproduction can arise because of positive externalities (Admati & Pfleiderer, 2000) and because financial statements constitute a public good that will be under-supplied in a free market (e.g., Gonedes & Dopuch, 1974; Beaver, 1998). The arguments in favor of regulation rather than the free market were influential in many European countries where private companies must publicly make their financial statements available. Those statements also had to be autonomously audited (Aranya, 1974; Dedman & Lennox, 2009). On the other hand, it remains unclear whether private incentives for the demand and supply of audits are insufficient, mainly as private markets for other forms of certification services are ubiquitous in the economy (Jamal & Sunder, 2008; Lennox & Pittman, 2011). Two principal theories can explain the demand for an audit:

1) Agency theory. Addresses the relationship wherein the principal engages another person to accomplish some service that involves deputing some decision-making authority to the agent. The segregation of ownership and control leads to information asymmetry that affects the owner’s ability to effectively monitor if the management has acted in their best interests (Jensen & Meckling, 1976).

2) Stewardship theory. Additionally, it documents that owners hire management to act in its owners’ best interest. Chae, Nakano, and Fujitani (2020) stated that the effect of audit quality is verified. Auditors can reduce risks by playing a corporate governance device mechanism to decrease agency costs. The improvement of technology and product innovation is positively related to the total productivity growth rate, which suggests that auditors play an important role in controlling an entity’s performance (Lee & Xuan, 2019).

One of the best ways to explain the role of auditing and its impact on lenders is agency theory (e.g., Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Watts & Zimmerman, 1983). Such problems can persist in complex and diverse SMEs (e.g., Ang, 1992; Eisenhardt, 1989; Hope et al., 2012), SMEs also have a high degree of information asymmetry (e.g., Fenn, 2000; Santos, 2006; Hope et al., 2012), especially SMEs which want to raise money through external debt financing, as a result, there is a principal-agent relationship between SMEs and lenders (e.g., Eisenhardt, 1989; Pentland, 1993; Power, 1999); SMEs seeking to raise funds through external debt are actively seeking ways to improve their quality accounting information (Burgstahler et al., 2006), thereby reducing the asymmetry of information between the SME and the lender (Jensen & Meckling, 1976).

Companies must acknowledge an audit’s benefit and value to reduce the information asymmetric and enhance the management’s financial statements’ verifiability. Kamarudin, Zainal, and Smith (2012) provide evidence that countries such as the United Kingdom, United States, Australia, and several European countries have exempted SMEs from the annual mandatory audit requirement. For instance, there is no mandatory audit requirement for SMEs other than listed companies in the USA and Egypt. In the case of the ASEAN region, other countries have different legislation of audit exemption. Effective June 2004, Singapore exempted its companies with a turnover of less than $5 million. On the other hand, Malaysia legally requires all companies to be audited annually, with no exemption.

The agency theory costs cited as one reason for the obliteration of mandatory audits for SMEs in other countries. Since SME is owner-managed, “it appears meaningless for an auditor to report to the shareholders that the directors have produced a true and fair picture of the financial statement of the business ... (Audit) is a great waste of money and resources” (Salleh et al., 2008). On the other hand, many studies proved that SMEs’ mandatory audits exemption adversely affects the SMEs themselves and the national economy (e.g., EFAA, 2019; Lennox & Pittman, 2011; Dedman & Kausar, 2012; Clatworthy & Peel, 2013; ICF & BMG, 2017; Eldaly & Abdul-Kader, 2018; Downing & John, 2018).

2.5. Cost-Benefit Analysis for Mandatory Auditing the Egyptian SMEs

A cost-benefit analysis (CBA) is a systematic process enterprises use to analyze which decisions to make and which to forgo. A CBA involves measurable financial metrics such as revenue earned, or costs saved because of the decision to pursue a project. The CBA sums the potential rewards expected from a situation or action and then subtracts the total costs of taking that action. A CBA can also include intangible benefits and costs or effects from a decision, such as an employee’s morale and customer satisfaction (Investopedia, 2021).

Any form of CBA implies that financial reporting decisions are guided by economic rationality. The model proposed by Weber M. (1968) suggests financial reporting is based on formal rationality, which is influenced by substantive rationality, which may reflect legal action (based on custom) and affective action (based on emotion).

From the CBA perspective, SMEs can feel the benefits of auditing by reducing other costs beyond the cost of SMEs’ auditing itself. It can be huge and can be a barrier to SME growth, such as the cost of debt (e.g., Blackwell et al., 1998; Kim et al., 2011; Minnis, 2011; Huguet & Gandía, 2014; Kausar et al., 2016; Huq, 2022) found that auditing decreases the cost of debt, while (Koren et al., 2014) found the opposite.

Some SMEs may not immediately perceive the value of audit and other services. So, it is vital to understand and respond to what the stakeholders need. The profession should better promote users’ understanding of audit and other services that meet those needs and develop new offerings or modify existing ones as the demands arise (EFAA, 2019).

Mandatory audits for Egyptian SMEs have many benefits. Although the audit process is not designed to detect fraud, there is no doubt that in the absence of an audit, fraud and errors are more likely to occur and go undetected without any independent examination (MIA, 2016). Independent audits provide far more than “public accountability” and have a crucial role in promoting ethical business practices throughout the economy. Moreover, an audit is crucial to guiding good governance in SMEs before they become economically significant, reducing the risk of business failure (Don & Dianne, 2010).

Through analyzing previous literature and investigating the actual Egyptian SMEs’ auditing market by questioning both auditors and SMEs’ owners/managers throw questionnaires and semi-structured interviews/phone calls to obtain a comprehensive vision of SMEs’ Audits (supply/demand). This study found that auditors support that mandating the Egyptian SMEs to audit financial statements will positively impact the audit market for SMEs and reduce audit costs. Also, in terms of cost and profit, the authors found that SMEs’ owners/managers support that the benefits of auditing for SMEs can outweigh the costs of auditing.

2.6. Mandatory Audits for Egyptian SMEs and Their Financing Opportunities

The International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) defined financial auditing as “the purpose of an audit (financial audit) is to fortify the degree of confidence of intended users in the financial statements, which is achieved by the expression of an opinion by the auditor on whether the financial statements are prepared, in all material respects, following an applicable financial reporting framework” (IFAC, 2018). The audit of financial statements reflects the accuracy of the company’s financial position.

In Europe, for a few years now, the deregulation of mandatory assurance of SMEs has been on the rise, while so too has the regulation of audits of broader entities (i.e., public interest entities). This deregulation for SME audits is mainly caused by governments raising audit thresholds and requiring fewer audits to be performed by law in response to calls to reduce the regulatory burden for small businesses. Although statutory demand for audit services decreases, demand for voluntary audits continues (IFAC, 2018; John & Kalina, 2016; Tesar & Zsuzsanna, 2017). While extensive proprietary and public companies are legally required to have their financial statements audited, the same does not apply to SMEs. However, there are times when it is desirable and sometimes mandatory for SMEs to undergo an audit.

Despite the importance of SMEs’ benefits for the economy, these companies face difficulties getting bank funding for their expansion and access to new markets. In Egypt 2009, in cooperation with the concerned authorities, the Egyptian Exchange established “Nile Stock Exchange” or NILEX. The first market in the region allows more financing opportunities for SMEs. Listed SMEs must get their financial statements audited in Egypt. The same does not apply to other SMEs. Although regulatory demand for all SMEs’ audits is not required, voluntary audits are increasing.

In alignment with “Egypt vision 2030”, the CBE obliged Egyptian banks to give out 20% of their total loans portfolio to SMEs, which is expected to provide 350,000 SMEs with 200 billion EGP within the upcoming four years at an interest rate of 5%. The loans’ interest rate is fixed at a 5% annual decreasing rate payable in 5 years (Yulia, 2019). Moreover, the CBE, in collaboration with the European bank for rebuild and development (EBRD) and the European investment bank (EIB), has availed funds to the banks to be “channeled unto SMEs and lowered requirements SME loans”. The qualifying companies under the program are SMEs with annual revenues ranging from1 million EGP and not exceeding 20 million EGP.

From an agency theory perspective, and according to literature. Arguably, mandatory audits for the Egyptian SMEs could affect the bank officers’ credit-granting decisions, subsequently affecting their financing opportunities by providing a reasonable assurance reducing information asymmetry between SMEs and lenders thereby, the first hypothesis becomes:

H1: Mandatory audits for Egyptian SMEs positively affect their financing opportunities.

2.7. Mandatory Audits for Egyptian SMEs as an Access to Finance

This study reached a generalization based on 11 semi-structured interviews/phone calls with Egyptian bank officers. Auditors’ reports—when available—significantly affect bank officers’ credit-granting decisions because of the Egyptian SMEs’ sector irregularities; it is comfortable to rely on a neutral opinion about the SMEs for credit-granting decision-making. However, they added other factors used in the credit-granting decisions, such as the SME’s reputation, experience with the client, the SME’s business goals, and the financial institution’s general risk policy.

By analyzing literature and discussions with bank officers, the authors determined four factors that mandatory audits can play a role in and affect the bank officers’ credit-granting decisions. These factors are confidence in SMEs, preferences among SMEs, borrowing eligibility for SMEs, and lowering the cost of debt. These factors together represent the SMEs’ financing opportunities.

2.7.1. Confidence

Confidence in credit clients plays a significant role in the credit-granting decision. The availability and reliability of financial statements are considered one of the fundamental factors influencing the confidence in SMEs (e.g., Kalya, 2013; Fatoki, 2014; Youssef, 2014; Gamage, 2015; Saleh, 2017; Boushnak et al., 2018). SMEs experience a phenomenon commonly known as “credit rationing” when low confidence. Credit rationing addresses situations where a company has difficulty obtaining the required bank loans and sufficiently favorable credit terms (e.g., Stiglitz & Weiss, 1981; Beck et al., 2005, 2006, 2008; Palazuelos et al., 2020). SMEs can voluntarily use auditor’s assurance and related services to assist in preparing reliable financial statements that meet the needs of both internal and external interested users. However, most Egyptian studies on accounting SMEs have ignored the need for and the importance of audit services and focused on the extent to which these companies need accounting standards that match their needs and skills (Saleh, 2017). While several studies (e.g., Carey et al., 2000; Tauringana & Clarke, 2000; Allee & Yohn, 2009) examined the demand for assurance services provided by auditors to SMEs, others (e.g., Wright & Davidson, 2000; Miller & Smith, 2002; Kim & Elias, 2007) examined the relationship between assurance services provided by auditors and the credit-granting decisions for SMEs. Additionally, the verification of the financial statements by an independent expert improves financial information credibility and assures different users (Defond & Zhang, 2014), so it may also influence lending decisions (Duréndez Gomez-Guillamon, 2003; Palazuelos et al., 2020). According to previous literature, it is arguable that SMEs’ mandatory audited financial statements affect the bank officers’ confidence in SMEs. Thereby, the hypothesis becomes:

H2a: Confidence positively affects bank officers’ credit-granting decisions.

H2b: Mandatory audits for Egyptian SMEs positively affect bank officers’ confidence.

2.7.2. Borrowing Eligibility

Many prior studies discussed the borrowing eligibility for SMEs as a vital consideration on lending SMEs. Most banks mainly follow the financial statements lending; in financial statement lending, a bank funds a loan founded on the solidity of an SME’s financial statements. Banks analyze an SME’s expected future cash flow to assess its loan eligibility. This method requires informative and dependable financial statements (CFRR, 2017; Berger & Gregory, 2006). The core of a successful loan is to overcome the problem of information asymmetry between the borrower and the lender that would otherwise create incentives for borrowers to default on their loans (Petersen & Rajan, 1994; Goldberg & White, 1998; Palazuelos et al., 2020). Fatoki, O. (2014) argued that banks require audited financial statements before lending to SMEs to assess their creditworthiness and mitigate the risk of defaults. Gamage, P. (2015) confirms that Sri Lankan SMEs face severe restrictions on bank lending access due to the lack of reliable financial information that banks need to make lending decisions. Zeneli, F. and Zaho, L. (2014) state that banks could not assess the applicant’s performance because the restrictions on funding for SMEs were due to the lack of factual financial information from SMEs in Albania. Kalya, E. (2013) acknowledged that the internal factor associated with the valuation of SME loans is the audited financial statements that can predict the ability to repay debt. Banks aim for reliable financial statements because they are sure that the company will generate enough income to pay off its debt. In their study in the US, Allee and Yohn (2009) found that enterprises with audited financial statements are less likely to be denied credit than those without, and these enterprises with accrual-based financial statements benefit in the form of a lower cost of capital. According to previous literature, it is arguable that SMEs’ mandatory audited financial statements affect their borrowing eligibility. Thereby, the hypothesis becomes:

H3a: Borrowing eligibility positively affects bank officers’ credit-granting decisions.

H3b: Mandatory audits for Egyptian SMEs positively enhance their borrowing eligibility.

2.7.3. Preferences

The reason for bank officers’ preferences among SMEs in the credit-granting decision is that SMEs are at high risk of default, and their financial statements are ambiguous (Yoshino & Taghizadeh-Hesary, 2016), this is what the literature understands by “opaqueness” referring to the difficulty SMEs face in providing reliable information about their actual status and performance (Berger et al., 2001; Berger & Frame, 2007; Hyytinen & Pajarinen, 2008), that explains why lenders may have preferences among SMEs in credit-granting decisions. Prior literature available in the credit-granting decisions field postulates that when the risk perceived by lenders is potentially very high, they may prefer to restrict their supply of funds or apply more stringent financing conditions for SMEs (Hodgman, 1960; Stiglitz & Weiss, 1981; Petersen & Rajan, 1994; Elsas & Krahnen, 1998; Palazuelos et al., 2020). So, lenders’ preferences go forward to audited SMEs in many cases.

In Egypt, some studies were done and addressed some remarkable findings. For example, Youssef I. (2014) reported that Egyptian SMEs are not targeting bank customers because no financial statements reflect the company’s solvency. Another study by Boushnak E. et al. (2018) found a significant relationship between the availability and credibility of audited Financial Statements with Credit Decisions for lending SMEs. Furthermore, the research provides knowledge for SMEs to know what banks’ preferences are. Additionally, Saleh, S. (2017) concluded that auditors’ services add value and preferability for SMEs by increasing the credibility of those SMEs’ financial information to get credit. That helps credit officers better grant credit decisions, thus getting the necessary funds to develop its operations and enhance its economic development role.

However, despite all formal procedures to support the credit-granting decisions, in many cases (or most), they are eventually based on the judgment and perceptions of bank officers (De la Torre et al., 2010; Palazuelos et al., 2020). For this reason, many authors argue that behavior is determined not by objective risk but by the impression, perception, and preferences that an individual has of it (Bauer, 1960; Mitchell, 1999; Palazuelos et al., 2020).

According to previous literature, it is arguable that SMEs’ mandatory audited financial statements give them a Preferability on credit-granting decisions. Thereby, the hypothesis becomes:

H4a: Preferences among SMEs positively affects bank officers’ credit-granting decisions.

H4b: Mandatory audits for SMEs positively affect preferences in favor of them.

2.7.4. Cost of Debt Assessment

The cost of debt is one of the main constraints for SMEs in borrowing from banks. Prior literature investigated the effects of auditing on lowering the cost of debt (e.g., Blackwell et al., 1998; Kim et al., 2011; Minnis, 2011; Huguet & Gandía, 2014; Kausar et al., 2016; Huq, 2022) found that auditing decreases the cost of debt, while (Koren et al., 2014) found the opposite. Huguet and Gandía (2014) investigated how mandatory or voluntary audits affect debt costs in the Spanish market where some, but not all, companies can reject the auditing. Kausar et al. (2016) mainly investigate the impact of voluntary audit decisions. However, Blackwell et al. (1998), Kim et al. (2011), Koren et al. (2014), and Minnis (2011) all limit the analysis to the part of the market where the choice of auditing is optional for the enterprise, Huq, A. (2022) found that enterprises with audited financial statements can reduce the cost of debt rather than other non-audited enterprises.

Evidence from the literature suggests various reasons for explaining business decisions to undertake voluntary audits. Dedman et al. (2014) examined the determinants of voluntary audit in a sample of 6274 companies recently dispensed with audits. Their results indicated that companies are more likely to purchase voluntary audits if: 1) have higher agency costs; 2) riskier (measured as those with lower accounting performance and riskier types of balance sheet assets); 3) wishing to raise capital; and 4) purchase non-audit services from their auditor. Overall, their results strongly support the idea that companies choose to audit when it is in their interests. Saleh, S. (2017) found that there are multiple motives behind the Egyptian SMEs’ voluntary demand for assurance and related services, such as: 1) the agency problems both between owners and management, and those between owners and creditors, 2) cost and benefit analysis of those services, 3) there is an agreement on the importance of the SMEs’ financial statements for getting credit, and 4) the audited financial statements are more reliable than those attached with limited review report or report on the compilation of financial statements. From antecedent submitting, it is arguable that SMEs’ mandatory audited financial statements influence the bank officers’ assessing the cost of debt. Thereby, the hypothesis becomes:

H5a: Lowering the cost of debt for SMEs positively affects financing opportunities.

H5b: Mandatory audits for Egyptian SMEs positively affect lowering the cost of debt.

Figure 1 summarizes the theoretical model according to the study’s hypotheses.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Approach

The study adopted an inductive strategy associated with a qualitative research approach was. The authors used the inductive strategy to discuss the research hypotheses because it is the best approach that links research methods to discuss the research hypotheses. The authors aimed to investigate the impact of mandatory Audits for the Egyptian SMEs on increasing their financing opportunities. The research depends on assessing Egyptian public interest in the SMEs Audits. Also, understanding and explaining the motives of increasing mandatory Audits for the Egyptian SMEs, rather than describing and testing a theory, is why an inductive approach is more suitable for this research.

3.2. Sampling Design

The universe of the study is made up of 1) Egyptian banks officers with different levels of responsibility in credit granting decision-making. Also, this study is concerned about 2) SMEs owners/managers and not focused on a specific industry or geographic area. Additionally, an overall view was needed to investigate 3) SMEs’ Auditors and 4) Academics/Economists about their opinions.

3.3. Sampling Approach

The authors had chosen the “snowball” sampling approach had been chosen, which means sending the electronic questionnaire (google forms) directly to respondents who asked to fill out the questionnaire and forward it to others they know to match the survey requirements. Also, the authors used social media specialists’ groups on Facebook, WhatsApp, and LinkedIn.

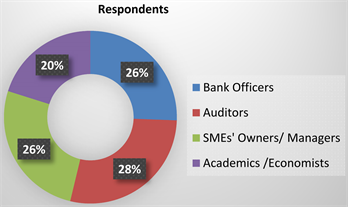

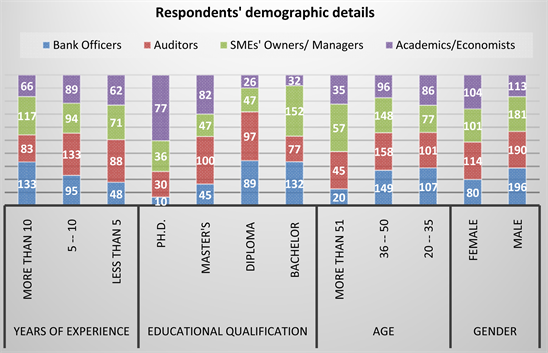

3.4. Collecting Data Methods

The authors used questionnaires and semi-structured interviews/phone calls to collect data. The questionnaires were four focused surveys designed and directed to four respondents: bank officers, auditors, SMEs’ owners/managers, and academics/Economists, as shown on Chart 1. Questionnaires for the SMEs’ owners/managers, auditors, and academics/economists consist of two main sections. The first included questions about the respondents’ demographic details as shown on Chart 2, and the second—depending on the occupation—had focused questions about the expected economic consequences of Egyptian SMEs’ mandatory audits. For reliability test the authors used Cronbach’s Alpha test as in Table 2 and the Likert interval range scale as in Table 3.

Bank officers’ questionnaire consists of three sections. The first included questions about bank officers’ demographic details as shown on Chart 2. The second consisted of four questions representing four factors as dependent variables theoretically assumed to affect the bank officers’ credit-granting decisions, thereby affecting SMEs’ financing opportunities. The third section included mandatory audits for SMEs Egyptian SMEs as an independent variable.

Chart 1. Respondents’ numbers.

Chart 2. Respondents’ demographic details.

![]()

Table 3. Likert interval range scale.

Most of the questions were close-ended questions anchored on a five-point Likert scale (Likert, 1932), ranging from “1”, “Totally Disagree”, to “5”, Totally Agree” Table 4 and Table 5 except two “Yes/No” open-ended questions Table 6.

The authors followed the most basic principles in designing the questionnaires such as comprehensibility, clarity, and neutrality.

3.5. Statistical Analysis and Results

Using the snowball sampling method, the authors obtained 1079 responses; the authors obtained empirical evidence from a survey of 276 bank officers, 304 auditors, 282 SMEs’ owners/managers, and 217 Academics/Economists in Egypt. Additionally, the authors conducted 41 semi-structured interviews/phone calls; 11 bank officers, 8 auditors, 13 SMEs’ owners/managers, and 9 academics/economists asked their opinions about the economic consequences of mandating auditing for the Egyptian SMEs. The authors used Microsoft Spreadsheets and SPSS V. 20 to get results, as shown in Tables 4-7.

To ascertain the validity of the questionnaire, the authors consulted some experienced academics and made modifications according to their recommendations.

![]()

Table 4. Descriptive statistics for mandatory audits for the Egyptian SMEs and effects on their financing opportunities.

![]()

Table 5. Do mandatory audits for Egyptian SMEs increase their chances of obtaining financing from banks?

![]()

Table 6. Open-ended yes/no questions.

![]()

Table 7. Correlation between mandatory audits for Egyptian SMEs and their financing opportunities.

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

The authors changed the sequence and wording for some questions to make them more understandable and relevant to the purpose of the study. These changes improved the face validity of the questionnaire (Taherdoost, 2016; Aithal & Aithal, 2020).

Moreover, the authors conducted a pilot survey test on some participants before being broadly circulated to the research sample. Some of the received comments from these early participants related to the wording of the questionnaire. For instance, they observed that some questions were not readily understood, so the authors simplified these questions’ wordings.

3.5.1. Cronbach’s Alpha Test

For Cronbach’s alpha test of reliability, the generally accepted rule is that α of 0.6 - 0.7 indicates an acceptable level of reliability (i.e., George et al., 2015; Creswell, 2005, 2010; Pallant, 2001; S ekaran, 1992), from Table 2 for all questionnaires α > 0.6 that make it acceptable.

3.5.2. Descriptive Statistics

As a result of using a five-point Likert scale (Likert, 1932), the authors took the decision according to the following scale interval range in Table 3.

Table 4 shows descriptive statistics for the mandatory audits for the Egyptian SMEs and effects on their financing opportunities. We find that the highest average belongs to question 3: (auditor’s report adds more confidence to the financial statements of SMEs that apply for loans) with a mean of 4.66 and Std. Deviation 0.683, followed by question 4: (auditor’s report enhances the chances of SMEs obtaining financing from banks) with a mean of 4.63 and Std. Deviation 0.740, followed by question 5: (mandatory audits for the Egyptian SMEs will increase their chances of obtaining financing from banks) with a mean of 4.54 and Std. Deviation 0.858, followed by question 1: (it is preferable to deal with SMEs that do financial auditing for their financial reports) with a mean of 4.53 and Std. Deviation 0.668. Finally, the lowest average belongs to question 2: (SMEs with audited financial statements have a lower cost of debt than others) with a mean of 3.77 and Std. Deviation 1.281.

The weighted average for SMEs’ financing opportunities (Section 1) was 4.39 with Std. Deviation 0.565, which indicates that the trend of (factors of financing opportunities as dependent variables) is “totally agree” as a general trend according to 5-point Likert scale as shown in Table 3 since laying in the interval (4.20 - 5.00).

The total weighted average was 4.42 with Std. Deviation 0.552, which indicates that the trend of (mandatory audits for Egyptian SMEs and effects on their financing opportunities) is “totally agree” as a general trend according to the 5-point Likert scale as shown in Table 3 since laying in the interval (4.20 - 5.00).

So, the average for (mandatory audits for the Egyptian SMEs and effects on their financing opportunities) is 4.42, which considers a high level since Table 3 shows the level intervals.

Table 5 shows descriptive statistics for “Do mandatory audits for Egyptian SMEs increase their chances of obtaining financing from banks?” among respondents, from which we find that the highest average belongs to auditors with a mean of 4.61 and Std. Deviation 0.837, followed by bank officers with a mean of 4.54 and Std. Deviation 0.858, followed by academics/economists with mean 4.47 and Std. Deviation 0.793. Finally, the lowest average belongs to SMEs’ owners/managers with a mean of 4.33 and Std. Deviation 0.902.

The weighted average was 4.49 with Std. Deviation 0.857, which indicates that the trend of (mandatory audits for SMEs can increase their financing opportunities) among respondents is “totally agree” as a general trend according to the 5-point Likert scale as shown in Table 3 since laying in the interval (4.20 - 5.00).

So, the average of “Do mandatory audits for Egyptian SMEs increase their chances of obtaining financing from banks?” among respondents is 4.42, which is considered a high level since Table 3 shows the level intervals.

The results obtained from Table 6 show that most SMEs’ owners/managers respondents, with 78.4%, see that the benefits of SMEs’ audits outweigh the costs of auditing. In contrast, two of the respondents think that it depends on the supply and demand, and perhaps other factors have an effect, such as the geographical area.

On the other hand, most auditors respondents with 89.5% see that Mandating the Egyptian SMEs to audit financial statements will positively impact SMEs’ audit market and reduce audit costs.

The results illustrate that the respondents had a high degree of knowledge and confidence in auditing in activating the Egyptian SMEs’ sector and their tendency towards mandatory auditing for this vital sector of the national economy.

3.5.3. Tests of Hypotheses

The results of spearman’s correlation coefficient between mandatory audits for Egyptian SMEs and their financing opportunities are in Table 7.

Spearman’s correlation coefficient showed positive associations between mandatory audits for Egyptian SMEs and their financing opportunities in Table 7 with Rs = 0.432 and p-value = 0.000. Also, it showed the strongest relation is with borrowing eligibility with Rs = 0.484 and p-value = 0.000, and the weakest is with preference with Rs = 0.185 and p-value = 0.002 as shown on Figure 2.

Given the above, the results of Testing the hypotheses are as follows in Table 8.

![]()

Figure 2. Research model correlation results.

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

4. Conclusion

This study empirically explores the role that mandatory audits for Egyptian SMEs can play on bank officers’ credit-granting decisions consequently SMEs’ financing opportunities. Additionally, it considers the perceptions of involved parties about the capability of Egyptian SMEs’ mandatory audits on their financing opportunities amongst the irregularities of that vital economic sector. Original data on bank officers, auditors, SMEs’ owners/managers, and academics/Economists’ perceptions of the variables mentioned above, collected using an online questionnaire additionally with semi-structured interviews/phone calls.

Some literature finds that regulation is quite positive and necessary for the audit profession to thrive (Vinten, 1999; Eldaly & Abdul-Kader, 2018; Quick et al., 2008; Hanh & Anh, 2020). In comparison, others state that the research demonstrates that regulation is not favored and is quite constricting (Dewing & Russell, 2002; Dewing & Russell, 1997). In the literature of mandatory audits for SMEs, we can find studies that indicate that it is preferred to mandate SMEs’ audits. For example, the European Federation of Accountants and Auditors for SMEs (EFAA) noted that European Commission (EC) and national regulators might have gone too far in exempting SMEs from having an audit and raising thresholds part of reducing the regulatory burden on SMEs.

One of the best ways to explain the role of auditing and its impact on lenders is agency theory (e.g., Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Watts & Zimmerman, 1983). Such problems can persist in complex and diverse SMEs (e.g., Ang, 1992; Eisenhardt, 1989; Hope et al., 2012). SMEs also have a high degree of information asymmetry (e.g., Fenn, 2000; Santos, 2006; Hope et al., 2012), especially SMEs which want to raise money through external debt financing. As a result, there is a principal-agent relationship between the SMEs and the lender (e.g., Eisenhardt, 1989; Pentland, 1993; Power, 1999).

From a theoretical point of view, by analyzing literature and discussions with bank officers, the authors determined four factors that mandatory audits can play a role in and affect the bank officers’ credit-granting decisions. These factors are confidence in SMEs, preferences among SMEs, borrowing eligibility for SMEs, and lowering the cost of debt. These factors together represent the SMEs’ financing opportunities.

Firstly, confidence in credit clients plays a significant role in the credit-granting decision. The availability and reliability of financial statements are considered one of the fundamental factors influencing the confidence in SMEs (e.g., Kalya, 2013; Fatoki, 2014; Youssef, 2014; Gamage, 2015; Saleh, 2017; Boushnak et al., 2018). SMEs experience a phenomenon commonly known as “credit rationing” when low confidence. Credit rationing addresses situations where a company has difficulty obtaining the required bank loans and sufficiently favorable credit terms (e.g., Stiglitz & Weiss, 1981; Beck et al., 2005, 2006, 2008; Palazuelos et al., 2020).

Secondly, borrowing eligibility for SMEs is considered a vital consideration for lending SMEs by many prior studies. Most banks mainly follow the financial statements lending as a bank fund a loan founded on the solidity of an SME’s financial statements. Banks analyze an SME’s expected future cash flow to assess its loan eligibility. This method requires informative and dependable financial statements (CFRR, 2017; Berger & Gregory, 2006). The core of a successful loan is to overcome the problem of information asymmetry between the borrower and the lender that would otherwise create incentives for borrowers to default on their loans (Petersen & Rajan, 1994; Goldberg & White, 1998; Palazuelos et al., 2020).

Thirdly, preferences among SMEs in the credit-granting decision are because SMEs are at high risk of default, and their financial statements are ambiguous (Yoshino & Taghizadeh-Hesary, 2016), this is what the literature understands by “opaqueness” referring to the difficulty SMEs face in providing reliable information about their actual status and performance (Berger et al., 2001; Berger & Frame, 2007; Hyytinen & Pajarinen, 2008), that explains why lenders may have preferences among SMEs in credit-granting decisions. Prior literature available in the credit-granting decisions field postulates that when the risk perceived by lenders is potentially very high, they may prefer to restrict their supply of funds or apply more stringent financing conditions for SMEs (Hodgman, 1960; Stiglitz & Weiss, 1981; Petersen & Rajan, 1994; Elsas & Krahnen, 1998; Palazuelos et al., 2020). So, lenders’ preferences go forward to audited SMEs in many cases.

Fourthly, the cost of debt is one of the main constraints that make SMEs restrained from bank loans. The Prior literature investigated the effects of auditing on the cost of debt (e.g., Blackwell et al., 1998; Kim et al., 2011; Minnis, 2011; Huguet & Gandía, 2014; Kausar et al., 2016; Huq, 2022) found that auditing decreases the cost of debt, while (Koren et al., 2014) found the opposite. Huguet and Gandía (2014) investigated how mandatory or voluntary audits affect debt costs in the Spanish market, where some companies can reject the auditing. Huq, A. (2022) found that SMEs with audited financial statements can reduce the cost of debt rather than other non-audited enterprises.

The results obtained confirm that mandatory audits for the Egyptian SMEs positively affect their financing opportunities. Also, mandatory audits for the Egyptian SMEs positively affect the bank officers’ credit-granting decisions.

Finally, for limitations and further research, it must take into account that the geographical scope of the study is limited to Egypt. Also, the authors focus on the bank officers’ credit-granting decisions, which may not precisely match their effective behavior. In any case, bank officers face daily decisions on whether to give credit, so their responses to the survey likely reflect their perceptions and behavior in past real situations. Moreover, bank officers’ perceptions and intentions are essential indicators for understanding SMEs’ cognitive processes underlying credit-granting decisions.

Based on the study’s interviews/phone calls, it is helpful in future research to examine the effect of other variables which increase SMEs’ financing opportunities and influence bank officers’ credit-granting decisions. Such as the SME’s reputation, experience with the client, the SME’s business goals, and the financial institution’s general risk policy.