Driving Forces towards the Adoption of Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices: Empirical Evidence from Manufacturing Industries in Ethiopia ()

1. Introduction

Throughout the world, sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) is an emerging concept and its popularity has been growing and received great interest both in the practitioners and in the academic world in the last few decades. Carroll & Shabana (2010)stated that“...today,one cannot pick up a newspaper,magazine or journal without encountering some discussion of the issue,some recent or innovative example of what business is thinking or doing about corporate social responsibility (CSR),or some new conference that is being held”on sustainability or social responsibility activities. This statement clearly and boldly depicted that, a sustainability issue is a hot and contemporary world agenda.

The concept of sustainability was first acknowledged at the global level through the report of the World Commission on Environment and devolvement Brundtland (1987) which is known as the Brundtland Commission. By coining, the term sustainable development, Brundtland Commission, defined sustainability, as the “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs”. As stated by Dyllick & Hockerts (2002) later on the 1992 Earth summit, which is held in Rio de Janeiro, increased the wide acceptance of this definition by politicians, business leaders, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

According to Seuring & Müller (2008) because of customer pressure and legislation in developed countries, firms take the sustainability of the supply chain as the main goal that to be achieved. Further Fabbe-Costes et al. (2011) stated that most countries in the world are interested in environmental issues and large-scale industries are developed to increase their production capacity in order to respond to free markets. Therefore, balancing the conflicting pressure, which is often created by firm-level sustainable development among economic performance, environmental degradation, and social disruption, is a main challenging task for firms (Matos & Hall, 2007).

An empirical study conducted by Rasool et al. (2016), on Pakistan textile firms stated that green supply chain management (GSCM) has great implications on environmental, corporate social responsibility, firms’ profitability, and strong completion across the globe. As stated by many scholars (Li & Toppinen, 2011; Morali & Searcy, 2013; Rasool et al., 2016) in the course of few recent decades, the enhanced government regulations and the extent of public awareness, customers, employees, investors, NGOs, and other stakeholders have intensified pressures on firms and incited them towards sustainability to effectively balance economic, ecological, and social ramifications of their activities. Accordingly, many firms have adopted a certain level of dedication to sustainability practices. According to Carter & Rogers (2008), for the last three decades, better attention was given to sustainability, as it is an indispensable condition for long-lasting profitability and for being competitive enough for firms in their business environment. This major consciousness is often initiated from both internal and external pressures, such as legislative factors, different stakeholder actions and pressures (Winter & Knemeyer, 2013).

This article is organized into nine sections. Accordingly, the first section is an introduction which highlights the concepts and backgrounds of sustainability. The second section discusses a detailed literature review on driving forces and practices of sustainable supply chain management practices. The third section presents materials and methodology applied in order to address the objective of the study. The fourth section covers results and discussions on the level of integration among the supply chain members in moving towards the adoption of SSCM. The fourth section covers, results and discussions on driving forces towards the adoption of sustainable supply chain management and sustainable supply chain management practices. The fifth section presents results of inferential statistics on driving forces and sustainable supply chain management practices. The rest (sixth, seventh, eighth, ninth and tenth) sections present conclusions, limitations, direction for future research, acknowledgments, and conflict of interest statement respectively.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Driving Forces towards the Implementation of Sustainable Supply Chain Management

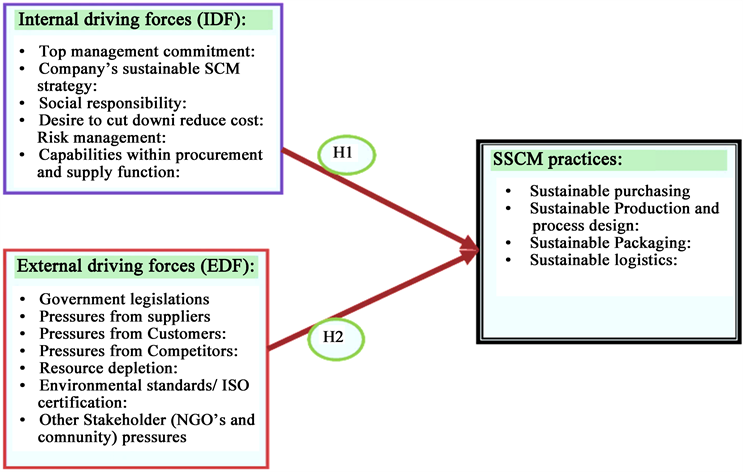

Even if different driving forces influence firms towards the adoption of SSCM Walker et al. (2008) broadly grouped the major driving forces that have been influencing firms for promoting sustainability practices into two (internal and external) main categories. According to Shultz & Holbrook (1999), external pleasures such as competitive pressures from competitors, government regulations, and pressures from customers are very critical for balancing both environmental and economic performances by organizations. An empirical study conducted by (Zhu & Geng, 2013) in China shows that, the government has been developing different approaches for environmental management like promoting technologies of cleaner production, more strict environmental regulations, and encouraging environmental management systems (ISO1401) certification.

2.1.1. Internal Driving Forces

Different kinds of literature reviewed showed that various internal driving forces influence firms towards the adoption of SSCM practices. The most common and widely identified are:

1) Top management support and commitment

According to Hunt & Auster (1990) for the development and implementation of environmental resource management (ERM) senior managements are chief in motivating and guiding the organization. According to (Carter et al., 2000; Niemann et al., 2016)top management commitment and support are critical in driving and enabling firms towards the successful implementation of SSCM practices. Previous scholars (Walker & Brammer, 2009) finding depicted that top management commitment is positively associated with the introduction of environmental policy/GSCM. According to Hanna et al. (2000), employee and middle management involvement also creates positive results on firms’ environmental and social sustainability. McMurray et al. (2014) stated that the implementation of green procurement is related to the influence of organizational leadership, policy, organizational strategy and finance which needs top management commitment and support. According to Carter & Jennings (2004) environmental development programs necessitate high resources support that is influenced by top management commitment.

2) Company’s sustainable supply chain management strategy

The establishment of SSCM strategy by companies can influence firms towards the implementation of SSCM. According to González-Benito & González-Benito (2010) as it will be essential for firms to break down corporate sustainability strategy into appropriate supply chain sustainability strategies to achieve maximum performance. Further, the study conducted by Li & Toppinen (2011) suggested that a strategy that is based on corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a differentiating factor and its implementation would improve the relationship of a given company with its stakeholders and improve companies’ profitability.

3) Social responsibility

According to Bhool & Narwhal (2013) social and environmental responsibility is one of the driving forces, which influences firms to evaluate and get the responsibility of their operational negative impact on the social and environmental aspects of sustainability. Maloni & Brown (2006) stated that to adopt sustainability, firms are highly influenced to show that as they have a concern and social responsibility. For instance according to Wang & Sarkis (2013) implementation of GSCM practice depicts that how much concerns are given by the firms to the society and it is an indication of they are worried about the social aspects of sustainability such as labours justice, health care, and safety.

According to (Jones et al., 2005; Rehman & Shrivastava, 2011) various firms build their reputation and brand image by organizing charity fundraisers and giving donations in the best interest of the less-privileged people. Furthermore, as per Agan et al. (2013) corporations those interested to enhance their image, frequently make public their activities regarding environmental protection to give a picture of their commitment and concern for their stakeholders and the public at large.

Now a day, many firms are engaged in CSR and feel socially and environmentally responsible. Matten & Moon (2008), stated that recently corporations’ particularly in Europe, Australia, Southeast Asia, South America, and Africa have begun to adopt the practice of CSR. Andersen & Skjoett-Larsen (2009) in their study by visiting one trading area called Trading Area South East Asia (TASEA) headquarter in Bangkok, which covers Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam stated that for practicing CSR supply chain needs the involvement of entire organizations. They also stated that experience sharing, training both employees and key personnel at the supplier level, placing a large purchase order and forming long term contracts with suppliers as an incentive and regularly auditing supplier’s performance has to be required for effective implementation of CSR. An empirical study conducted in India by Sriyogi et al. (2013), depicted that,CSR is the one being practiced by the majority of manufacturing firms of their study.

4) Desire to cut down/reduce cost

According to Lee (2008), every firm has a desire to reduce its costs for fetching business gains to increase profit. From earlier studies (Carter & Dresner, 2001) stated that the aspiration to cut down costs by firms is one of the driving forces for green/environmental sustainable supply chain projects. Further Porter & Van der Linde (1995) discussed that, in the form of wasted materials and efforts, pollution reflects hidden costs throughout the product life cycle. Therefore, according to Handfield et al. (1997) a desire to cut down costs, elimination of wastes, and quality improvements are the main initiatives that drive firms towards the implementation of green supply chain activities.

5) Risk management

Seuring & Mueller (2008) identified competitive advantages and prevention of organizations’ reputation loss (risk), as key driving forces for SSCM. According to Walker et al. (2008), the inability or unwillingness of the company to become environmental-friendly could directly cause reputational damage. Rasool et al. (2016) stated that by producing green products for consumers that protect the natural environment, firms can build their brand image and increase market demands for their products. Golicic & Smith (2013)’sfinding froma meta-analysis on environmentally SSCM practices and firm performance by examining a research work of over 20 years (from 1990-2011) depicted that, a positive and significant link between overall environmental supply chain practices with firm performance.

From many empirical studies conducted on driving forces, an investigation conducted on89 China automotive enterprises by Zhu et al. (2007) finding shows that, internal driving forces highly influence Chinese automobile supply chain enterprises to practice GSCM. Moreover, (Holt & Ghobadian, 2009) identified that in UK internal driving forces highly influence manufacturing organizations towards GSCM practices than external driving forces.

Consequently, in view of many scholars (Handfield et al., 1997; Hanna et al., 2000; Carter et al., 2000; Carter & Jennings, 2004; Zhu et al., 2007; Walker & Brammer, 2009; Holt & Ghobadian, 2009; Bhool & Narwhal, 2013; Golicic & Smith, 2013; Niemann et al., 2016) empirical and theoretical literature the researchers hypothesized that:

H1.Internal driving forces have a positive and significant effect on sustainable supply chain management practices.

2.1.2. External Driving Forces

After an extensive literature review, the most dominant and widely stated external driving forces are presented here below.

1) Government legislations

Luthra et al. (2011) stated that government legislations set the rule of game and organizations are obliged to follow international, national, and regional regulations and fulfill customer requirements. According to Sathiendrakumar (2003), the beginning of extreme global warming and change in climate has enforced governments to enact laws on the environmental and social impacts of organizations by intending to control pollution and reduce environmental damages. Even though different meetings were held and formulated legislation on climate change at an international level, the United Nation Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which is held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, and the Kyoto Protocol, that held in Japan in December 1997 are the two distinguished examples (Lenssen et al., 2008). These legislations and treaties require far-reaching sustainability reporting and auditing of pollution, as well as emission control and look forward to encouraging companies to incorporate sustainability within their core business processes.

According to Jaffe et al. (2005)government, rules and legislation are external driving forces that encourage organizations to reduce the use of non-renewable resources and limit green gas emissions. Chaabane et al. (2012) in their study on “Design of sustainable supply chains under the emission trading scheme” in Canada, indicated that in order to have a significant drive on environmental strategy at the global level, the existing Emission Trading Schemes (ETS) and legislation must be strengthened and synchronized.

According to Zhu et al. (2007) Chinese automotive supply chain managers have been enforced to consider and start the implementation of GSCM practices in order to enhance their environmental and economic performances due to high pressures from different bodies at different levels in different directions. They identified that regulative (legislative) pressures are the major driving forces/ pressures for GSCM practice adoption followed by market pressures.

An empirical study by Holt & Ghobadian (2009) depicted that, on average government legislation highly influence UK manufacturing firms towards GSCM. According to Biehl et al. (2007) statement, the implementation of the legislation has been making industrials responsible for the collection, treatment, recycling and environmentally safe disposal of their products. Further (Rehman & Shrivastava, 2011) presented that government regulatory pressure is one of the external driving forces that highly influence the adoption of SSCM by firms. Because regulations increase the threats of fines for non-compliance companies, which results in increasing organizations’ costs in the form of penalties and fines (Bhool & Narwal, 2013).

2) Pressures from suppliers

Different scholars stated their views as suppliers play key roles in the implementation of sustainability. For instance, Carter & Dresner (2001) stated that suppliers through providing valuable ideas can help firms in the implementation of green projects but they do not directly drive firms towards sustainability.

3) Pressures from Customers

According to Walker et al. (2008), the more reputed the organization, the more it becomes sensitive to customer pressure since the company’s bottom line is impacted directly by the customers’ attitudes. Therefore, the inability or unwillingness of the company to become environmental-friendly could directly cause reputational damage. Brammer & Walker (2011) in their study entitled “Managing sustainable global supply chains” identified and ranked consumer pressure, government regulation and legislation, pressures exerted from the public, and NGOs are the four most significant and prevalent driving forces in pressuring firms towards SSCM. Further (Carter & Jennings, 2004; Giunipero et al., 2012) discussed that, the end customers pressure and demand for green product design and manufacturing highly influences firms towards SSCM.

4) Pressures from Competitors

According to, Ferguson & Toktay (2006) organizations must realize a competitive advantage for themselves in order to be more watchful to the needs of customers. For instance, Gold et al. (2010) stated that green purchasing policy may not be undertaken only due to a desire to ‘save the world’ rather as it is one of the ways through which companies achieve a competitive advantage and enhance their financial performance. According to Giunipero et al. (2012), offering sustainable products by firms proactively can enable them to have a competitive advantage in the market place than their competitors. Further, McMurray et al. (2014) stated that, firms’ ability to compete against their competitors is positively strengthened through improving financial performance, by setting better labour standards and improving working conditions for employees’ safety and health. Therefore, competitors’ pressure is one of the main driving forces that influence firms towards the adoption of SSCM.

5) Resource depletion

According to (Hodge, 2009) since there is a battle between supply chains for natural resources, it is indispensable to launch proactive measures in order to safeguard these resources for the coming generations. The main objective of most firms is to make economic returns as much as possible within a short time scale. Cost reduction would be realized by the means of efficiency in energy usage, recycling wastes, competent use and reuse of raw materials, and improvement in safety standards.

6) Environmental standards/ISO certification

The International Organization for Standardization introduced ISO 14001 in 1996 to assist organizations in mitigating risks resulting from the environmental impacts of their actions (Nawrocka et al., 2009). According to Kannan et al. (2008), ISO 14001 does not set targets for industries rather it was only intended as a benchmark to assist organizations to achieve their environmental objectives. ISO 14001 recommends information gathering and open communication between trading partners to standardize processes in an environmentally friendly manner (Curkovic & Sroufe, 2011). Viadiu et al. (2006) stated that for suppliers to meet their current selection, the main requirements are environmental related policies, health and safety standards, appropriate working conditions and code of conduct.

According to Zhu et al. (2005) fulfillment of international standards and regulations such as ISO14001, “Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment” (WEEE), “Restriction of Hazardous Substances” (RoHS) and others are among the main external driving forces in influencing firms to adopt SSCM practices. Both WEEE and RoHS are requirements/rules laid down at the European level that firms who are interested and wish to sell their products in the European Union must fulfill. The purpose of WEEE is to prevent the build-up of electrical and electronic waste by encouraging waste minimization through reuse, recycling, and other forms whereas, RoHS is used to restrict the use of certain hazardous substances such as lead in electronic equipment.

Many scholars, (Handfield et al., 2001; Montabon et al., 2007) finding reveals that due to the release/introduction of voluntary and international standards such as ISO 14001 certification and growing pressures of the government emphasis on west reduction highly influences firms towards the movement of environmental responsibility. Handfield et al. (2001) stated that the desire to be environmentally friendly is commencement to influence the decision regarding product design, process design, green purchasing, and manufacturing practices. Klassen & Vachon (2003)’s finding shows that companies’ efforts to invest more in environmental management practices are significantly associated with ISO 14001 certifications.

7) Other Stakeholder (NGO’S and community) pressures

As was discussed by (Zhu et al., 2005; Giunipero et al., 2012), one of the main external driving forces is the public movement towards higher environmental responsibility which increases pressures on firms in the adoption of SSCM practices. According to Appolloni et al. (2014), when the firms do not consider green procurement practices, it may result in public/community resistance and negatively affects organizational reputation.

According to Wang & Lin (2007), pressures by NGOs on firms are through boycotting or through designing adverse publicity campaign to shame companies that offer unsustainable products. González-Benito & González-Benito (2010) presented that both governmental organizations and NGOs were found as the most important drivers for the execution of sustainability strategies for corporate firms. However, Holt & Ghobadian (2009) empirical finding shows that, community and individual customers’ pressure is low in influencing UK manufacturing firms towards GSCM practices.

Some scholars in their empirical studies collectively illustrated the impact of external driving forces on the adoption of SSCM practices. For instance, Ageron et al. (2012) finding depicted that external driving forces do have a positive impact on the development of sustainable supply management than internal driving forces. Another empirical survey study conducted by Meera & Chitramani (2014) on 155 manufacturing Industries in Tamilnadu, India to find out the implementation of GSCM practices and the extent of driving forces influence on GSCM practice depicted that, GSCM practices are positively related and significantly influenced by both internal and external driving forces.

Therefore, based on the above empirical and theoretical literature reviewed such as (Zhu et al., 2005; González-Benito & González-Benito, 2010; Ageron et al, 2012; Giunipero et al., 2012; Meera, & Chitramani, 2014; Tay et al., 2015) and other scholars works on major external driving forces towards the adoption of SSCM practices, the researchers hypothesized that:

H2.External driving forces have a positive and significant effect on sustainable supply chain management practices.

2.2. Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices

Even though some authors classify SSCM practices into two broad categories i.e., sustainable purchasing practices, and sustainable manufacturing and logistics practices, as stated by different scholars in many works of literature reviewed under this study the main SSCM practices were classified into four sub-groups based on their function all the way throughout the supply chain.

1) Sustainable/green purchasing practices

One of the key aspects of the green and sustainable supply chain is the use of green procurement practices (Varnäs et al., 2009). The sustainable supply chain is affected by the purchase practices of raw materials that are either reusable or recycled (Rasool et al., 2016). The manufacturer has to create awareness among its suppliers and assist them to establish environment-welcomed practices to reduce air emissions, solid and liquid wastes, and discharge of hazardous chemicals and effluents into the environment (Shi et al., 2012). An empirical study conducted by Beyene (2015) in Ethiopia, shows that green purchasing, organizational commitment and marketing practices are not well considered by the Ethiopian Tanneries to green the supply chains.

2) Sustainable product and process design

Lenvis & Gretsakis (2001) stated that the main reason why we need a focus on product design is that different types of products have different environmental, social and economic impacts at all stages of the product life cycle. For instance product disposition highly depends on actions taken at its design stages (Liew et al., 2006). According to Chaabane et al. (2012) integrating principles of life cycle assessment (LCA) at the supply chain/process, the design phase maximizes long-term sustainability. Many studies conducted by different scholars elucidated that green supply chain practices and environmental decision tools positively affect environmental and corporate/commercial performance (Handfield et al., 1997; Darnall et al., 2008). However, an empirical study conducted by Beyene (2015) depicted that, eco-design and environmental practices are not well considered by the manufacturing firms under Ethiopian tanneries industry groups to green their supply chain.

3) Sustainable Packaging

Conceptual framework.

According to, Zhang & Zhao (2012) now a day’s in society there is a shortage of resources and the accessibility of resources for use has turned out progressively rare. Nevertheless, most of the packaging items are single-use, and swing to squander after use and the item life cycle of them is short which leads to extensive usage of resources for packaging which threats the natural condition through extraordinary danger. Zhang & Zhao (2012) stated that the consumption of resources and packaging in a large amount will generate a lot of waste.

Therefore, packaging materials should be minimal and light in weight and be recyclable. In other words, it has to be used as many times as possible before its disposal and bio-degradable (Zhu et al., 2012).

4) Sustainable Logistics

In supply chain transportation has many potential negative impacts on the environmental, economic and social aspects of SSCM and these impacts can be presented in monetary values by estimating and calculating all direct, indirect and avoidance costs (Cetinkaya et al., 2011). As cited by Cetinkaya et al. (2011) according to Kågeson (1993) in Europe the external costs related to transportation such as noise, accidents, and pollution are estimated from 3% - 5% GDP of Europe. According to Cetinkaya et al. (2011), one of the major transportation negative impacts on the social aspects of SSCM is its accidents. From its negative environmental impacts, carbon dioxide (CO2) contains many harmful gases and particles which negatively impact the environment. Reverse logistics is one of sustainable logistics practices considered as a process that guarantees the use and re-use of the value put into products (de Brito, 2004). Based on the above literature reviewed, the above conceptual framework was developed by the researchers to portray the effect of driving forces on SSCM practices.

3. Materials and Methodology

3.1. Research Design, Approach, and Strategy

According to Saunders et al. (2009) based on the purpose of the study most often the research design can be classified into threefold namely, exploratory, descriptive, and explanatory. Therefore, based on the purpose of the study both descriptive and inferential types of research designs were used and found more appropriate for this study in order to address the pre-determined objectives.

According to Creswell (2014), quantitative, qualitative or mixed approaches are the three research approaches in social research. As primary data was collected in a close-ended questionnaire, which is developed in five (5) point-Likert-scale types, a quantitative research approach was used for this study. Furthermore, as presented by Saunders et al. (2009) the most common and subsequently considered research strategies are (experiment; survey; case study; action research; grounded theory; ethnography; and archival research). As this study was conducted throughout the country on large-scale firms of the selected manufacturing industries in Ethiopia, survey type of research strategy was used and found more appropriate.

3.2. Sources and Methods of Data Collection

According to Kothari (2004),the researcher should keep in mind, the two sources of data (primary and secondary) sources when deciding the methods for collecting the data used for the investigation undertaken. Therefore, both primary and secondary sources of data were used in this study. Accordingly, primary data was collected through questionnaires while articles, books, journals were used as secondary sources of data. The items used in this study were adopted from various previous studies and developed by the researchers from theoretical and empirical literature. To mention few of these sources (Carter et al., 2000; Niemann et al., 2016; González-Benito & González-Benito, 2010; Walker et al., 2008; Giunipero et al., 2012; Meera & Chitramani, 2014) are the major ones.

3.3. Sampling Methods

According to the Ethiopian Central Statistic Agency (CSA, 2016), based on the nature of products produced the manufacturing industries in Ethiopia were stratified into fifteen categories. The scope of this study is limited only to four major large-scale manufacturing industry groups namely: 1) Food products and Beverage; 2) Manufacturing of Textile; 3) Tanning and dress of Leather; 4) basic Iron and Steel manufacturing industries groups. The total number of large-scale manufacturing firms in the aforementioned four industrial categories throughout the country in the year 2014/15 is 405 (CSA, 2016). According to Kothari (2004), the size of the sample should neither be excessively large, nor too small. According to Cooper & Schindler (2008), the ultimate test of a sample design is how well it represents the characteristics of the population it senses to present. Therefore, Yamane (1967)’s formula as provided below was applied to determine the sample size for this study.

where: n = sample size; N = population size; and e = precision level/sampling error. Note: with a precision level (sampling error) of e = 5%, and N = 405 firms. Therefore, through proportional stratified simple random sampling technique, 201 sample firms were selected by Yamane’s formula and then from each sample firm by using a purposive sampling technique three top and middle managers (respondents) were selected. Therefore, in total 603 questionnaires were distributed to 201 sample firms (i.e., 3 * 201 = 603). However, out of 201 sample firms, only 146 firms filled and returned questionnaires. Finally, valid questionnaires used for analysis were 420, because about 18 questionnaires were invalid and rejected by the researchers. The collected data was analyzed using mean, standard deviation, and regression statistical tools. The summary of the number of firms in each industry, the number of sampled firms, the number of firms returned questionnaire and the valid response rates were shown in Table 1 below.

3.4. Reliability and Validity Test

Regarding validity, content validity was checked before the distribution of questionnaires. According to (Straub et al., 2004) content validity is a judgment, by experts about the extent to which, the observed variables/summated scales accurately/fully contain and evaluate the domain of the concept intended to measure. They also stated that content validity could not be determined statistically. That means the content of validity can be tested or evaluated through referring literature and asking experts in the area.

Therefore, based on the recommendations forwarded by the above-mentioned scholars’ to determine the content validity of this study both literature and experts’ opinion was used. Accordingly, after reviewing much literature, several questions were formulated and adopted from previous studies. Then, experts in the fields of (supply chain management, procurement, and logistics) in both academics and practical environments were asked to review and put their comments on this initial questionnaire. Based on their recommendations, from the initial questionnaire, a small number of items were added, deleted, and to some extent modified and the questionnaire was finalized.

There are a variety of methods for calculating internal consistency (reliability), among them the most commonly used one is Cronbach’s alpha (α) (Saunders et al., 2009). Moreover, as stated by Eisinga et al. (2013) the acceptable Cronbach’s

![]()

Table 1. Distribution of firms in the population and actual participants.

alpha (α) value is (≥0.70) which proves the dependency of instruments. Therefore, after the relevant data was collected from the sample respondents, the reliability (internal consistency) test was conducted by using Cronbach’s alpha (α). Accordingly, the result was illustrated in Table 2.

As it can be seen from Table 2, all of the reliability tests of Cronbach’s Alpha values are (≥0.70) which shows that the reliability of all the variables under this study is acceptable.

3.5. Methods of Data Analysis

Finally, the collected data was analyzed quantitatively by using different descriptive and inferential statistical tools such as, mean, standard deviations, correlations, and regression.

4. Results and Discussion

This part presents both internal and external driving forces for the adoption of SSCM practices descriptive, the Pearson correlation coefficient, and regression analysis. All items were collected by 5 points Liker-type-scale which represents 1 = very low, 2 = Low, 3 = Moderate, 4 = high, and 5 = very high. Therefore, based on the given response by the sample respondents the descriptive part was analyzed by mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) statistics.

Even though there is no hard and fast rule for Likert-type-scale items to determine the cut point or range of values, the cut point or mean value range used for this study is supported by other previous scholars’ work for instance (Beyene, 2015; Muangpan, 2015). Accordingly, an item or group mean (sub-grand mean) that achieved a mean score value of (M > 3.5, M ≥ 2.50 but < 3.50, and M < 2.5) depicts that high, moderate, and low respectively. Besides the mean score values an item that scored a standard deviation greater than one (SD > 1.0) implies as there is a significant difference/inconsistency among respondents.

![]()

Table 2. Result of reliability test.

4.1. Internal Driving Forces for the Adoption of SSCM Practices

In order to examine the internal driving force category, about seven items (driving forces) were adopted by the researchers from various preceding studies. Accordingly, the sample respondents’ response mean, and the standard deviation was presented in Table 3 below.

As illustrated in Table 3, the first driving force what the sample respondents were asked to rate is about top management support and commitment towards SSCM implementation. According to the sample respondents’ response, the mean score value (M = 3.46) with the standard deviation of (SD = 1.095) was obtained. Nevertheless, its standard deviation bared a significant difference among the sample respondents the mean score value gives a picture that large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia were moderately influenced by their top-level management support and commitment in moving towards embracing SSCM practices.

From earlier studies, Walker & Brammer (2009) identified that the top management’s personal commitment positively affects the introduction of environmental policy, and Carter & Jennings (2004), boldly stated that due to environmental development programs requires strong resource, top-level management support is an indispensable driving force. Moreover Beyene (2015)’s finding on“Green supply chain management practices in Ethiopian tannery industry” revealed that top management commitment towards “greening” the whole supply chain in the Ethiopian tannery industry is carried out to some extent. Therefore, the above analysis indicates that on average the top management support and commitment moderately influenced or pushed large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia towards the adoption of SSCM practices along their supply chains which is highly consistent with (Walker & Brammer, 2009; Beyene, 2015).

In the same Table 3, regarding the 2nd, and 3rd driving forces i.e., the extent of employees’ involvement and firms’ sustainability strategies the mean score value of (M = 3.35 and M = 3.45) with a standard deviation (SD = 1.047 and 1.084) was obtained respectively. Even if, there is a significant inconsistency among the sample respondents on both driving forces among the respondents the mean score values indicate that on average employees’ engagement, and SSCM strategies

![]()

Table 3. Internal driving forces towards SSCM.

were found moderately drives large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia towards the adoption of SSCM practices in their supply chains. Therefore, what can be understood and concluded from this analysis is that the extent of companies SSCM strategies in Ethiopia large-scale manufacturing firms is somewhat promising but it needs more concerns and engagement of the firms in developing and adopting well organized and documented SSCM strategies.

From the seven internal driving forces, the highest mean score value (M= 3.69) was obtained on social responsibility with a standard deviation value of (SD = 0.882). This denotes that one of the top major internal driving forces that highly influence large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia towards the adoption of SSCM in their supply chains is their social responsibility. The standard deviation shows that no significant difference among the sample respondents regarding social responsibility is being a top internal driving force that enforces their firms towards the adoption of SSCM. This finding is highly supported by the preceding studies, (Jones et al., 2005; Rehman & Shrivastava, 2011) stated that various firms build their reputation and brand image by organizing charity fundraisers and giving donations in the best interest of less-privileged people. Therefore, what can the above finding indicates that large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia are engaged in corporate social responsibility that can build their brand image.

In order to generate better profit, every business firm has the aspiration for reducing its costs. The mean score value obtained from the sample respondents on the extent of desire to cut down/reduce costs is (M = 3.55) with a standard deviation of (SD = 0.671). The standard deviation indicates that no significant difference among the sample respondents regarding a desire to cut down costs being highly influencing their firms towards SSCM. The mean score value implies that a desire to cut down costs is one of the internal driving forces that highly push large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia towards the implementation of SSCM practices. From this analysis, what can be understood is that cost shrinkage/reduction could enable firms to have a competitive advantage through cost leadership and fetch better profit from their business. Among the preceding studies, this finding is consistent with (Handfield et al., 1997; Lee, 2008) as they identified a desire to cut down the cost as one of the main internal initiatives that highly influence/drive firms towards the adoption of green supply chain activities.

Concerning risk (reputational and environmental risk) management internal driving force the second highest mean score value (M = 3.66) next to corporate social responsibility with a standard deviation of (SD = 0.762) was scored. This noticeably depicted that on average risk (reputation and environmental-related risk) management highly motivates large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia towards the adoption of SSCM practices. This is since once firms lose their reputation it is very difficult to rebuild their image easily. From earlier studies, this finding is highly consistent with Seuring & Mueller (2008) who identified competitive advantages and prevention of organizations’ reputation loss, as key driving forces for the adoption of SSCM. Further, Rasool et al. (2016) discussed that by producing green products for consumers that protect the natural environment, firms can build their brand image and increase market demands for their products.

Regarding capabilities within purchasing and supply function mean score value (M = 3.46) and standard deviation of (SD = 1.131) was obtained. This implies that on average the purchasing and supply function capability of large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia to some extent influenced them towards the adoption of SSCM practices in their supply chain. From prior studies, Krause et al. (2009) boldly stated that a firm is no more sustainable than its suppliers because the purchasing function of any firm becomes fundamental in the realization of their sustainability effort.

Finally, the amassed mean score value (M = 3.52) was obtained. This shows that collectively on average large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia particularly (Food and Beverage, Textile, Leather, and Basic Iron and steel) industries were found highly influenced by internal driving forces towards the execution of SSCM practices in their supply chain.

4.2. Analysis of External Driving Forces for the Adoption of SSCM Practices

In order to examine or asses, this category of deriving forces about seven external driving forces was adopted by the researchers from previous studies. Accordingly, the mean and standard deviation of the sample respondents’ was presented in Table 4 below.

As it was illustrated in Table 4, the sample respondents were requested to rate the extent to which these external driving forces have been influencing their firm towards the implementation of SSCM. Accordingly, government regulation and legislation scored a mean value of (M = 3.62) with the standard deviation of (SD = 1.093). Even though the standard deviation shows a significant inconsistency

![]()

Table 4. External driving forces towards SSCM.

among the respondents the mean score value symbolizes that on average government rules, regulation and legislation (pressures from the government) have been highly enforcing large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia towards the implementation of SSCM practices in their supply chains. Many earlier studies were found highly consistent with this finding. For instance, an empirical investigation conducted by Zhu et al. (2007) in China and a literature review conducted by Tay et al. (2015) in India depicted that the government regulative (legislative) pressure is the first and the highest driving forces for the execution of SSCM. Additionally, (Walker et al., 2008; Seuring & Mueller, 2008; Walker & Brammer, 2009; Brammer et al., 2011) findings also confirmed that the government rules and regulation compliance, as highly influence firms towards the adoption of SSCM practices. Therefore, it can be concluded that government regulations do have a great impact on enforcing manufacturing firms to adopt SSCM practices in their supply chains.

Regarding the suppliers’ green program in driving the manufacturing firms towards the adoption of SSCM mean score value (M = 3.29) with a standard deviation of (SD = 1.024) was obtained. It implies that on average suppliers greening program to some extent drives/pushes large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia towards the execution of SSCM practices.

The mean score value of respondents on customers’ pressure in driving firms towards SSCM is (M = 3.85) with a standard deviation of (SD = 0.971). As we can witness in Table 3, the highest mean score value, with the lowest SD (no significant difference) among the sample respondents was obtained on customers’ pressures. This elucidates that customers’ pressure is one of the top important external driving forces that highly pressurized large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia to execute SSCM practices. This finding was highly supported by many earlier studies’ findings. For instance, Walker et al. (2008) boldly discussed, the more reputed the organization is, the more sensitive the company becomes to customer pressure since the company’s bottom line is impacted directly by the customers’ attitudes. Further, (Seuring & Mueller, 2008; Brammer & Walker, 2011; Tay et al., 2015) finding showed that consumer pressure is one of the most significant and prevalent external driving forces (pressures) on the organizations in moving towards the execution of SSCM practices in their supply chains.

The mean score value obtained from the sample respondents on competitors’ actions (pressures from competition) is (M = 3.62) with a standard deviation of (SD = 0.973). This shows that pressure from competitors is one of the external driving forces that highly persuade (influence) large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia towards the adoption of SSCM in their supply chains. From preceding studies, Ferguson & Toktay (2006), in their study entitled “The effect of competition on recovery strategies” stated that fundamentally an integration of sustainability in the supply chain among the supply chain partners was undertaken in order to improve competitiveness among rivals. Therefore, based on the above analysis, it can be concluded that the existence of competition among the competitors’ (pressures from competitors) plays a great role in influencing firms to implement SSCM practices.

Regarding resource depletion/reduction in resources, the mean score value of (M = 3.11) with a standard deviation of (SD = 1.176) was obtained. This elucidates that the reduction/depletion of resources to some extent persuades large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia towards the implementation of SSCM practices. According to Hodge (2009) since there is a battle between supply chains for natural resources it is indispensable to launch proactive measures in order to safeguard these resources for the coming generations. However, the result obtained in this study does not reflect as such strong concerns were given by Ethiopian large-scale manufacturing firms regarding the depletion of resources and its pressure in influencing them to adopt SSCM practices was found moderate.

The sixth external driving force that was rated by the respondents in this study is compliance with international standards and regulations. The mean score value of the respondents regarding compliance to standards such as ISO Certifications is (M = 3.54) and the standard deviation is (SD = 1.221). This indicates that the existence of compliance to standards (ISO Certifications) requirements highly influences manufacturing firms towards the execution of SSCM practices. The hard-line truth is that when firms are involved in international trade, some countries request suppliers to present different ISO or equivalent certificates. For instance, suppliers must present “Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment” (WEEE), “Restriction of Hazardous Substances” (RoHS) to sell their products in European Union markets (Zhu et al., 2005). Montabon et al. (2007) stated that environmental management practices are becoming popular since the existence of voluntary and international environmental standards. In addition, (Zuckerman, 2000) discussed that to address environmental performance through the use of environmental management systems (EMS) the release of ISO 14001 standard is used as additional pressure on some industry supply chain. This finding was found consistent with the aforementioned scholars.

Regarding exposures from other stakeholders (NGOs, local community, and other pressure groups) in impelling the large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia towards the adoption of SSCM mean score value of (M = 3.06) with the standard deviation of (SD = 1.075) was scored. Relative to other external driving forces other stakeholders (public, NGOs, and other pressure groups) were found feeble/weak in driving large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia towards the adoption of SSCM practices. From previous studies, Brammer et al. (2011) identified pressures exerted from the public, and NGOs play a very significant role in moving firms towards the execution of SSCM. Therefore, based on the above analysis it can be concluded that, even if NGOs, the public, and other pressure groups have abundant opportunities in influencing organizations towards the adoption of SSCM, in case of Ethiopia their level of pressure is not adequate. The reasons for its low pressure in Ethiopia might be a lack of community awareness about SSCM, lack of interest and commitment by NGOs, and other pressure groups. This finding was found consistent with an empirical finding of Holt & Ghobadian (2009) which signified the society/community and individual customers’ pressures are least in influencing UK manufacturing firms in moving towards the adoption of GSCM practices.

Finally, the amassed mean score value of external driving forces was conducted and it is (M = 3.44) which implies that collectively external driving forces influence large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia moderately.

4.3. Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices

As stated in the literature review section, SSCM practices were grouped into four major categories. These are green purchasing, sustainable product and process design, sustainable packaging, and sustainable logistics. Each of these SSCM practices was assessed by different items or observable variables.1

As it was illustrated in Table 5, sustainable packaging practices scored a mean value of (M = 3.54) with a standard deviation of (SD = 0.690). This denotes that large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia were highly considered and well practicing sustainable packaging practices. Regarding green purchasing, sustainable product and process design, and sustainable logistics practices scored mean value of (M = 3.30, 3.42, and 3.40) with a standard deviation of (SD = 0.610, 0.703, 0.651 and 0.690) respectively. This implies that, large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia have been moderately adopted green purchasing, sustainable product and process design, and sustainable logistics practices. All practices standard deviations demonstrated that there is no significant disparity among the sample respondents. Finally, the amassed mean score value of (M = 3.42) indicates that collectively on average large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia

![]()

Table 5. Sustainable supply chain management practices.

were moderately adopted SSCM practices which is auspicious progress. Therefore, it can be inferred from the analysis is that, even though the current SSCM practice is somewhat promising a lot of tasks have to be undertaken and firms have to go afar distance to enhance their SSCM practices in their supply chains.

For more elucidation, SSCM practices were demonstrated graphically in orderto exhibit the sample respondents’ responses concerning the adoption of the SSCM practices by large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia.

As we can see from Figure 1 below, sustainable packaging practices with a mean value of (M = 3.54) is highly practiced whereas, green purchasing is not well considered by large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia that needs ever more emphasis for realizing SSCM along the supply chains. Relatively product and process design and logistics practices are somewhat promising practices adopted by large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia.

5. Results of Inferential Statistics on Driving Forces and Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices

Besides the above descriptive (mean and standard deviation) analysis, inferential statistics such as correlation analysis were conducted to assess the association between internal driving forces (IDFr), external driving forces (EDFr), and sustainable supply chain management practices (SSCMpra). Furthermore, in order to examine the extent of the explanatory (internal and external driving forces) variables explain the variance in the explained (SSCMpra) variable, multiple regression analysis was performed.

5.1. Correlation Analysis

For this study, the researchers used Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient in order to determine the relationship among internal driving forces (IDFr), external driving forces (EDFr), and sustainable supply chain management practices (SSCMpra). Accordingly, the correlation matrix table was presented in Table 6.

As illustrated in Table 6 above, the Pearson correlation coefficient result shows a positive and significant relationship between sustainable supply chain management practices (SSCMpra) with internal driving forces (IDFr) by (r = 0.574, at 1 percent significant level). The correlation coefficient between external driving forces (EDFr) and sustainable supply chain management practices (SSCMpra)

![]()

Figure 1. Mean distributions of sustainable supply chain management practices.

![]()

Table 6. Correlation between SSCM practices, internal, and external driving forces.

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

is positive and significant as the value at r = 0.582, at a 1 percent significance level. At the same time, the correlation coefficient between internal and external driving forces also indicates a positive and significant relationship since the (r = 0.665, at a 1 percent significance level). Therefore, as demonstrated in the above correlation matrix table, there is a positive and significant relationship among SSCM practices, internal, and external driving forces.

5.2. Regression Analysis of Internal and External Driving Forces on SSCM Practices

The most common and highly recommended regression assumptions such as collinearity, normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity were conducted before running the analysis and testing the hypothesis. Therefore, all of these assumptions were found fit and satisfied as presented in Table 7.

![]()

Table 7. Summarized regression assumptions and results.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Table 8. Regress internal and external driving forces as an independent variable on sscm practices as a dependent variable.

aPredictors: (Constant), EDFr, IDFr.

aDependent Variable: SSCMpra; bPredictors: (Constant), EDFr, IDFr.

aDependent Variable: SSCMpra.

Therefore, after all these assumptions were tested, the statistical regression was conducted. The regression results were presented in Table 8.

In order to evaluate the statistical significance of the regression model, it is very important to look into Table 8 of the ANOVA part. Therefore, the multiple regression analysis results above clearly depicted that, F = 139.835 at 2 and 417 degrees of freedom is statistically significant which implies that, the model is statistically significant. The determination coefficient (R2) for the SSCM practices of this model is 0.401 (40.1%) which indicates that about 40.1% of the variance of a dependent variable (SSCM practices) was explained by the linear combination of explanatory variables (internal and external driving forces).

The test outcome as shown in Table 8, which represents coefficients, that reveals the sustainable supply chain management practices (SSCMpra) and internal driving forces (IDFr) is strongly supported by the collected data by unstandardized regression coefficient of (β = 0.219, significant at 1 percent significant level). This implies that an increase in internal driving forces collectively have positive and significantly improves the adoption of SSCM practices by large-scale manufacturing firms. This finding is consistent with several prior studying for instance (Handfield et al., 1997; Jones et al., 2005; Maloni & Brown, 2006; Lee, 2008; Seuring & Mueller, 2008; Walker & Brammer, 2009; Rehman & Shrivastava, 2011).

In the same table, the collected data also depicted that external driving forces have a positive and statistically significant impact on the implementation of SSCM practices by (β = 0.293, significant at 1 percent significant level). A change or an increase in the extent of external driving forces is positive and significantly improves the adoption of SSCM practices by large-scale manufacturing firms. This inferential finding is highly supported by other previous studies to mention few (Zhu et al., 2005; Seuring & Mueller, 2008; González-Benito & González-Benito, 2010; Ageron et al., 2012; Giunipero et al., 2012; Meera & Chitramani, 2014; Tay et al., 2015). This implies that the existence of driving forces either internal or external significantly and positively influences manufacturing firms in adopting SSCM practices in their supply chains. Therefore, the finding of the above statistical tests of regression outcome strongly supported the (H1) and (H2).

6. Conclusion

Social responsibility, interest to manage reputational and environmental-related risk, and desire to cut down costs are the three top major internal driving forces whereas, pressure from customers, Government regulation and legislation, pressures from competitors, and international standards (ISO certifications) requirement are the top four major external driving forces those highly coercions large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia towards the adoption of SSCM practices. The statistical test confirmed that both internal and external driving forces have a positive and statistically significant effect on the adoption of SSCM practices. Concerning SSCM practices, sustainable packing was highly emphasized while green purchasing practices are not well considered in Ethiopia.

7. Limitations of the Study

Despite the valuable contribution of this study to the SSCM body of knowledge and practitioners, like other previous studies this study was not without any limitation, even if the impact of such limitations does not compromise the reliability and validity of the study output. The major limitations of this study are: First, the scope of this study was limited to only four large-scale manufacturing industries (Food and Beverage, Textile, Leather, and Basic Iron and steel) it does not incorporate medium and other large-scale manufacturing firms. Second, the data used in the study was collected by using only Likert-scale type which is perception based. Third, the respondents were only from manufacturing firms i.e., it does not include suppliers and customers’ perceptions. Therefore, the above mentioned shortcomings may be limits to generalizing about driving forces towards the adoption of sustainable supply chain management practices on overall Ethiopian manufacturing industries and to some extent, it limits the quality of the findings.

8. Directions for Future Research

Despite the above limitations based on the foundation provided by this study on driving forces towards the adoption of SSCM practices, some more important and attention-grabbing areas suggested for further research works are: the future researchers shall incorporate other manufacturing industry categories. Furthermore, apart from the Likert-scale, other methods of data collection tools have to be used. Future researchers are also recommended to incorporate both suppliers’ and customers’ perceptions to provide an encompassing elucidation on the effect of driving forces on the adoption of SSCM practices.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to all sample participants (respondents) in the surveyed organizations for their cooperation by spending their invaluable time in filling up the survey questionnaires.

NOTES

1For more elucidation on each items or observable variables, refer Balda & Singh (2020). Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices in Ethiopian Manufacturing Firms, International Journal for Research in Engineering Application & Management, 5(1), 235-243. DOI: 10.18231/2454-9150.2019.0304.