A Corpus-Based Study: A Comparison between Native Speakers and Chinese EFL Learners in Using Adjectives in Argumentative Writings ()

1. Introduction

Writing is an important productive ability for EFL learners (Zhai, 2016), and according to many kinds of research, one of the major problems on EFL/ESL learners’ academic writing lies in vocabulary, especially in the simplicity of the lexical features, accuracy and vocabulary richness (Francis, 1994; Parrott, 2010; Hinkel, 2002, 2003). For instance, Read (2000) states that many FEL learners rely on a very restricted range of vocabulary and grammatical structures in academic writing, which could limit them from expressing meaningfully and clearly. Research on 33 EFL Learners at a University in Indonesia finds that some students have difficulties in choosing a correct word for certain sentence context in Essay writing. In addition, some students used nonacademic words to express their ideas in their academic essay (Ariyanti & Fitriana, 2017). However, a large amount of research on lexical parts of academic writing is conducted on nouns and verbs (Goulden, Nation, & Read, 1990; Chafe, 1994; Hinkel, 2002, 2003; Bhatia, 2014), and the adjectives, although accounting for a large amount of proportion in English academic writings, the functions of which receive inadequate attention (Deveci & Ayish, 2021) and are insufficiently introduced to students, and therefore requires more research.

Besides, as a series of Chinese national opening up policies bringing English learning to the public attention, a rapidly increasing number of Chinese EFL learners attend standard international English tests such as TOFEL and IELTS, and large-scale Chinese EFL writing data are becoming more obtainable for collection, which might attribute to insufficiency of the publicly available extensive Chinese EFL learner corpora with standardized analysis and assessment criteria (Abe, Kobayashi, & Narita, 2013).

The study aims to explore differences in using adjectives between Native Speakers and Chinese Learners at two different levels of EFL proficiency in academic writing by comparing and analyzing research data taken from three sub-written corpora of The International Corpus Network of Asian Learners of English (ICNALE). With the findings, this research hopes to gain a deeper understanding of vocabulary learning practices of Chinese learners and provide some implications for both the learning and teaching of academic writing in English as a foreign language (EFL) context.

2. Literature Review

2.1. English Adjectives

Although not as numerous as other lexical elements such as nouns or verbs, adjectives in English appear frequently in academic writing (Biber et al., 1999), on account that they usually work as modifiers of nouns, noun phrases and pronouns, and to give information about people or things (Cobuild, 2005; Parrott, 2010; Hinkel, 2002, 2003). Hence the adjectives, somewhat share the similar importance with nouns that they describe (Hinkel, 2003). The adjectives have two major syntactical structures: the attributive adjective and the prescriptive adjective, of which the former structure is often used before a noun or noun phrase as a modifier (Hinkel, 2002, 2003). For instance, the adjective in the sentence “Lily is making a beautiful dress” functions as an attributive adjective, and the main purpose of the sentence is to state that lily is making a dress, while the adjective “beautiful” is for giving extra information about the dress. Similar examples are as follows:

1) He was wearing a white T-shirt.

2) …a technical term.

3) …a pretty little star-shaped flower bed.

(Examples are from the Collins Cobuild English Grammar, the digital edition)

The latter syntactic structure, namely, prescriptive adjective, works as the subject compliment and comes after a linking verb such as be verbs or become (Collins Cobuild English Grammar, the digital edition). For example, the adjective used in the sentence” The dress Lily is making is beautiful” is a prescriptive adjective, the purpose of which, unlike the descriptive adjective, is to describe the dress, and thus the focus is on the adjective “beautiful”. Similar instances are as follows:

1) The roads are busy.

2) The house was quiet.

3) He became angry.

(Examples are from the Collins Cobuild English Grammar, the digital edition)

Both descriptive and prescriptive adjectives function as lexical and strategic hedges in academic writings (Hyland, 1998). According to Francis (1994), to employ attributive adjectives in academic texts always requires a wider range of lexical resource, on account that the descriptive adjectives often serve as the attitudinal and classificatory element for textual cohesion; while the employment of prescriptive adjectives, according to Chafe (1994), seems to restrict the information to convey, as this kind of adjective usually follows the linking verbs, and thus the sentence structures are always simplified.

2.2. CIA and Corpus-Based Study

The establishment of International Corpus of Learner English (ICLE) accelerates the development of Contrastive Interlanguage Analysis (CIA), which is a learner’s corpus research with the purpose to examine learners’ L2 use by comparing and contrasting what native and non-native speakers do under a controlled situation (Granger, 1996). CIA, as Granger et al. (2009) state, is a powerful interlanguage analysis framework as it uncovers some L2 features that have not been focused on in the past but could be noteworthy for L2 learning. Since then, a lot of research on L2 learning are conducted under this framework, especially on the aspect of academic writing, which appears to be very important yet problematic for the increasing number of EFL/ESL students. For instance, Granger & Tyson (1996) explore the features of discourse connectors in French ESL writings by comparing which with writings of native English speakers adopting a button-up discourse research methodology, and the result shows that the French L2 writings don’t appear to have a significant overuse of connectors compared with the native speakers yet another qualitative analysis reveals that individual connectors are overused. Hinkel (2002) conducts research between native American English speakers and non-native speakers by analyzing written data from a writing corpus of 242 native and 1457 non-native writing samples, and the analysis result reveals that compared with the native American English speakers, the non-native learners coming from Japan, Korea, Vietnam and Indonesia have significantly low frequency rates in using attributive adjectives, with medians from 2.86 to 3.62 compared with a median of 4.05 of the native writers. Another CIA research on academic writing explores the various linguistic features of the native and non-native writing samples by comparing the writing samples of Native speakers and four groups of Asian speakers from The International Corpus Network of Asian Learners of English (ICNALE), and the result reveals that the Japanese English learners use less attributive adjectives compared with the native speakers (Abe et al., 2013).

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Questions

The study aims at investigating the differences between native speakers and Chinese EFL learners in using adjectives in argumentative writing. Towards this end, we seek answers to the following questions:

1) Do Chinese EFL academic writers and native academic English writers significantly differ with reference to the use of adjectives?

2) Do Chinese EFL academic writers of different language levels significantly differ with reference to the use of adjectives?

3.2. Data Collection

The data used here comes from The International Corpus Network of Asian Learners of English (ICNALE), a learner corpus with 5600 writing samples of 200 English native speakers as well as 2600 college students from 10 Asian countries and areas, learning English as a second language (ESL) or foreign language (EFL) (see Table 1) (Ishikawa, 2013). The ICNALE strictly controls the writing conditions such as topics, length, and time, so as to keep the corpus data as homogeneous as possible for the contrastive interlanguage analysis (CIA) of different writing groups (Granger, 1998; Ishikawa, 2013). This written database categorizes the language proficiency of the EFL and ESL participants, with reference to their scores in the standard English tests such as ETS, Cambridge ESOL and VST, into four levels: A2 (Wastage), B1_1 (Threshold: lower) and B1_2 (Threshold: higher), B2+ (Vantage or higher), which, as the developer claims, is more in accordance with the variety of Asian Learners’ English proficiency (Ishikawa, 2013; Hu & Li, 2015).

Since the purpose of this study is to explore the differences in the use of adjectives between the native speakers and Chinese EFL writers, hence only the writing data of the three sub-corpus will be used, namely, ENS, referring to the native writing corpus; CHN_A2_0, which is the corpus of the Chinese EFL writers

at beginner level; and CHN_B1_2, the Chinese EFL writing corpus of the intermediate level.

The argumentative writings in ICNALE have two set topics:

1) Is it important for college students to have a part-time job?

2) Should smoking be completely banned at all the restaurants in the country?

In order to make a reliable comparison between different writing groups, it is of necessity to strictly control the writing conditions and to make the corpus data as homogeneous as possible (Ishikawa, 2013). Therefore, the research only takes the writing data of topic 1 as the study corpus.

The searching adjectives for comparison of range and frequency are selected from the English Vocabulary Profile (EVP), which is an online vocabulary resource focusing on presenting plenty of words, phrases and idioms that worldwide English learners actually know rather than they should know (Capel, 2012). This online database classifies vocabulary from level A1 to C2 based on the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR), and referring to extensive authoritative linguistic sources such as the Cambridge Learner Corpus and Academic Word-lists, as well as the practical ones such as exam word lists and word lists in classroom materials (Capel, 2012).

3.3. Data Analysis

The study employs the UAM Corpus tool, version 3.2 (O’Donnell, 2008; Crosthwaite & Choy, 2016; Hu & Li, 2015) for assessing the overall frequency of using adjectives between native speakers and Chinese EFL learners by compiling all written data of the ICNALE into the UAM Corpus tool. The searching words are 200 one-word adjectives taken from the EVP website from the A1 to C2 level, which are input into the UAM corpus tool. The selection criteria of the searching adjectives are as follows:

1) Compound adjectives, including adjectives with hyphens are excluded from the selection in order to decrease the complexity of data processing as well as reduce the workload.

2) Polysemous adjectives with same forms only count as one word to avoid ambiguity in data analysis.

3) Comparative and superlative adjectives are also excluded from the searching list, on account that they are used merely in a limited range in academic writing (Hinkel, 2003) and mostly have fixed structures, hence can be taught with further focused pedagogical instructions.

After selection, 75 A1 leveled adjectives along with other 125 adjectives from level A2, B1, B2, C1, C2 are input into the UAM Corpus tool as the searching words for the comparison interlanguage analysis. The output data is then coded with a qualitative analysis in order to ensure that each searching word is used as an adjective in the data. For instance, the searching words “well”, “first”, “next”, “back”, “last” are in fact used as adverbs, and “fun”, “contrary” as nouns, as presented below in the three comparison writing groups, and hence are excluded from the result.

1) As is known for all, having a part-time job requires us to balance study and part-time job well (CHN_PTJ0_210_A2_0).

2) More importantly, working together with the employees, …they can learn how to get on well with the colleagues (CHN_PTJ0_311_B1_2).

3) I hope that they are not finding themselves so busy with their part-time job that they no longer can have enough time to do their homework well and… (ENS_PTJ0_044).

4) With a little bit of caution, you can acquire money, friendship, practice and fun in the same time (CHN_PTJ0_374_B1_2).

5) First of all, you can improve your comprehensive ability by taking part-time job…Next, you can make many friends during the job (CHN_PTJ0_015_B1_2).

6) Next, it would be interesting to see if there have been any studies upon how many hours they students can work before they begin to negatively affect their performance in school (ENS_PTJ0_063).

7) … he will never feel tired and on the contrary he will try his hard to do it (CHN_PTJ0_350_B1_2).

8) On the contrary, the college is a place where students can show their talent (CHN_PTJ0_064_A2_0).

9) As the saying goes, no man is an island, and having a part-time job is kind of like having a bridge back to the mainland (ENS_PTJ0_018_).

10) Last but not least. Of course we can earn… (CHN_PTJ0_033_B1_2).

4. Results and Discussion

The results and discussion are presented with comparison of three sub-corpus groups in two parts according to their frequencies distribution and over/under-used wordings.

4.1. Frequencies Distribution in Three Corpora

1) The overall frequencies

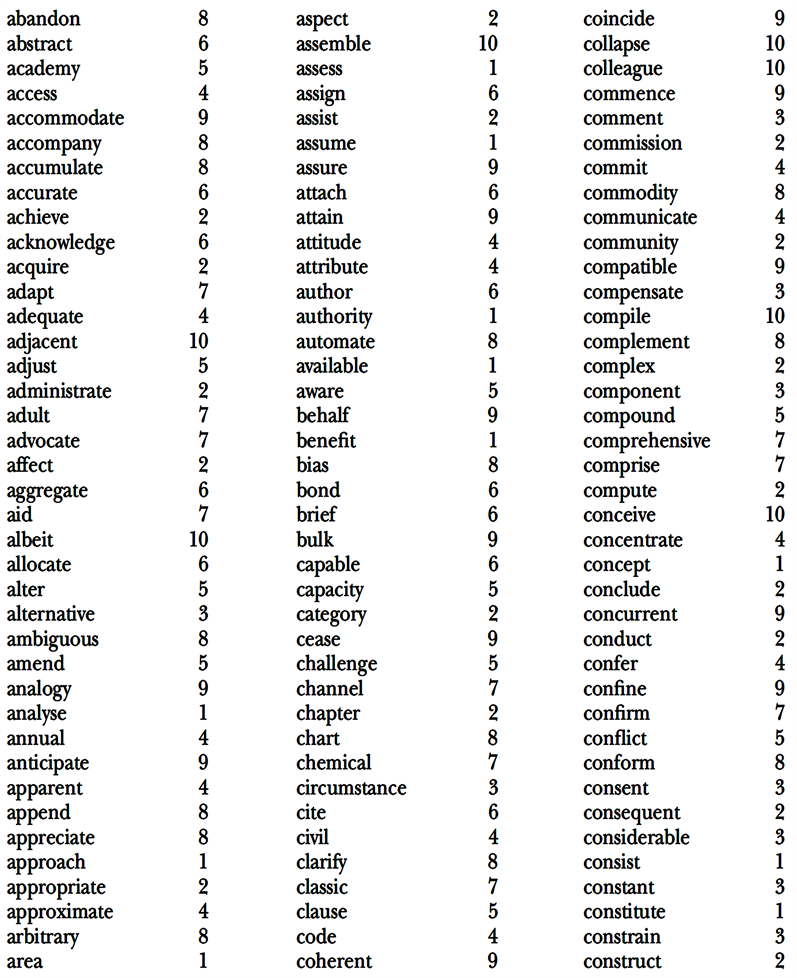

To calculate the overall frequencies in using adjectives between native speakers and Chinese EFL writers, the data is presented in the form of percentage according to token in Table 2, where “Beginner” refers to the sub corpus of Chinese EFL writings at level A2_0 in ICNALE, which contains 11029 words, and” Intermediate” is the sub corpus with Chinese EFL writings at level B1_1, B1_2 and B2+, with 26341 words in total, and the Native sub corpus includes 22,362 words.

As it is shown in the table, the Chinese EFL writers at beginner level accounts for the largest proportion of A1 level adjectives, with a number 33.18 per 1000 tokens; and the second most hits come from the native speakers, with a number of 32.83 per 1000 tokens, which is very close to that of the Chinese EFL beginners. For adjectives at A2 level, the most frequent users are native speakers, with a number of 13.02 per 1000 tokens, and the second largest users of words in this level are the Chinese intermediate EFL learners, with a number of 11.73 per 1000 tokens. For B1and B2 level adjectives, the most frequent users are from the intermediate EFL learners, with the percentage of 11.8 and 5.03 per 1000 tokens. The second frequent users of B1 level adjectives are beginners, with 10.63% per 1000 tokens. For C1 level adjectives, the most frequent users still, are the intermediate EFL learners, which accounts for 3.16 per 1000 tokens, and for C2 level adjectives, the native speakers take the largest proportion, with 1.08 per 1000 tokens.

2) The T-test of Frequencies Distribution of adjectives in Three Corpora

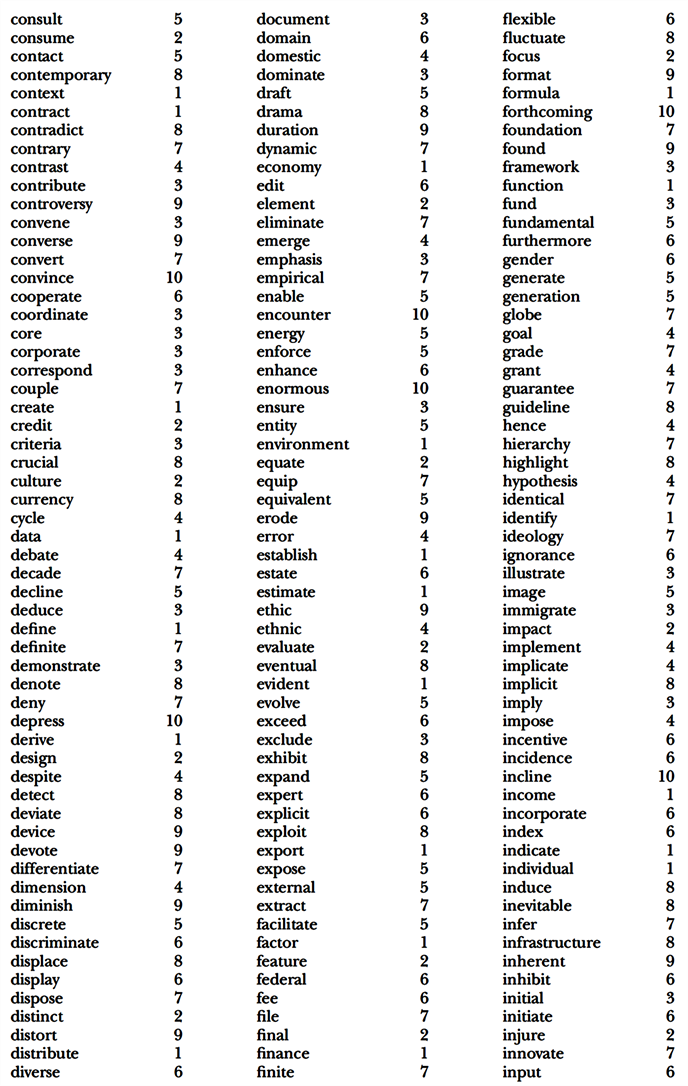

The research employs the T-test to examine whether the differences among three groups are significant, and the result is presented in Tables 3-5.

The T values in Table 3 indicate that the most significant difference between intermediate and beginner writers in frequency of using adjectives comes at level A1, with a high significant value of 4.119, which illustrates that there are many more Beginner writers who use the fundamental A1 level adjectives than intermediate learners. There is also a medium significance at level B2, with a T Stat value of 2.275, showing that intermediate learners tend to use much more adjectives at B2 level of CEFR than the beginner writers.

![]()

Table 2. Frequencies of using adjectives from level A1 to C2 in each writing group.

![]()

Table 3. The T statistics and the difference significance values between the beginner and intermediate level Chinese EFL learners.

Note: as Capel (2012) states, in the UAM Corpus tool, version 3.2, the symbol “+” represents the weak significance (90%), “++” is the medium significance (95%) and the “+++” stands for high significance.

![]()

Table 4. The T statistics and the difference significance values between the Chinese EFL intermediate writers and native speakers.

![]()

Table 5. The T statistics and the difference significance values between the Chinese EFL beginner writers and native speakers.

Seeing from the result in Table 2 and Table 3, the Chinese EFL intermediate level writers are capable of using higher leveled adjectives in a broader range when compared with the beginner level learners. According to the research on several standard English language proficiency tests, the application of the “lexical richness”, which refers to the relatively low-frequency vocabulary appropriate to the writing topic and style, plays an important role in overall written scores (Frase et al., 1998; Read, 2000).

As it is indicated from the data of Table 4, the NS group uses much more A1 level adjectives than their Chinese EFL intermediate counterparts, with a high significance and a T stat value of 3.769, while the EFL intermediate writers adopt many more words as B1level than the native speakers, with a T stat value of 4.184.

According to the T stat value in Table 5, the native speakers use more adjectives at A2 level compared with the beginner users, while the beginner writers apply more B1 level adjectives than the natives. For C2 adjectives, the natives only have a weakly higher significance value compared with their non-native counterparts.

The result of Table 4 and Table 5 is clearly different with the findings in previous studies in that “the native speakers adopt more sophisticated vocabulary than their non-native counterparts” (Frase et al., 1998; Hinkel, 2002), which may indicate that the native speakers don’t necessarily employ a larger range of adjectives than the Chinese EFL writers. However, the overall frequency rate alone may not be adequate enough to give information of all differences, and therefore it is of necessity to analyze the specific over/under-used wordings.

4.2. Overused and Underused Adjectives in Three Corpora

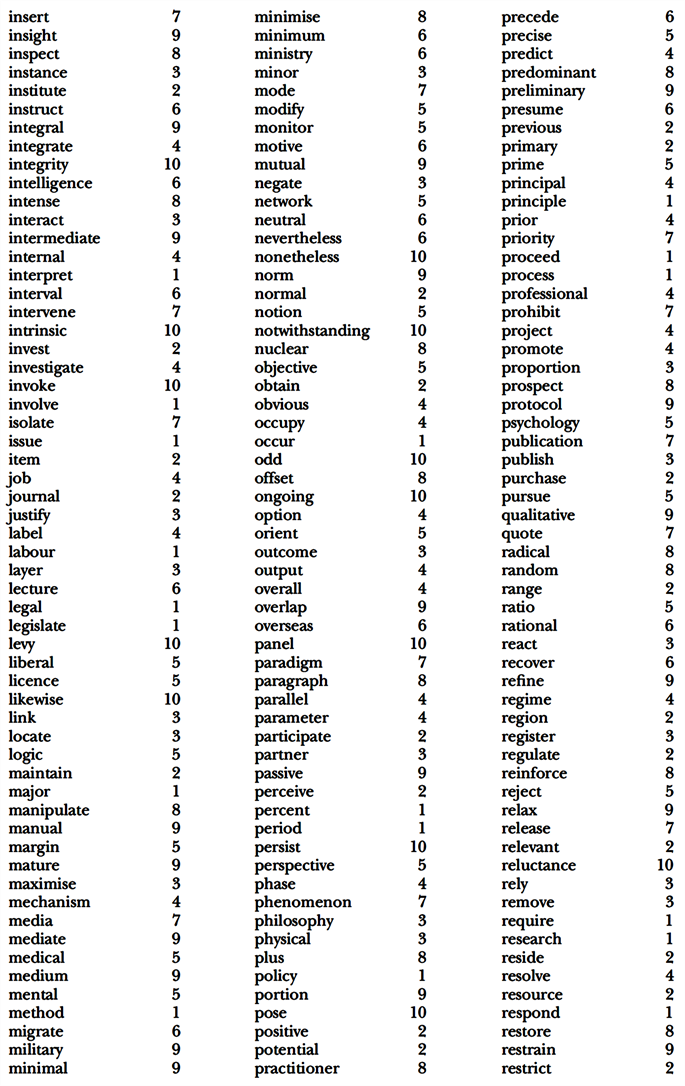

Tables 6-8 present the over/under-used adjectives by Chinese EFL writers comparing with the native speakers, using the Log-likelihood ratio test (LL = 6.63, p < 0.01).

At level A1, the beginner writers tend to overuse adjectives “important”, “good”, where the mostly overused word is “important”, with an LL value of 10, and at Level A2, the beginners seem to under-use the word “kind”, with a LL value of −7.20.

Examples of the over/underused adjectives are as follows:

I agree with the point that it is important that college students have part-time jobs (CHN_PTJ0_071_A2_0).

![]()

Table 6. The over-used and under-used adjectives by the Chinese EFL beginners comparing with the intermediate level writers.

![]()

Table 7. The over/under-used adjectives by the intermediate level Chinese EFL writers comparing with the native speakers.

![]()

Table 8. The over/under-used adjectives by the beginner level Chinese EFL writers comparing with the native speakers.

Finding work is good way to stop this from happening (CHN_PTJ0_058_A2_0).

What we can get from this kind of work is no more than a tiny bit of money, because this kind of work doesn’t involve any thinking or cooperation (CHN_PTJ0_362_B1_2).

When compared with the native speakers, there are many under-used adjectives by the intermediate learners, including “same”, “new”, “ready”, “fun” and “lucky”, with most of which coming from the A1 level. Among these words the most underused one is “new” at A1 level, with a LL value of 21.01, the second most underused adjective by the intermediate writers is “same”, with a LL Value of 15.71, which appears 60 times in the native writings while only 30 time in the intermediate writings.

The result indicates that the native speakers tend to use more fundamental adjectives than Chinese intermediate EFL learners.

The examples of these over/underused key words are as follows:

1) This will not only enable you to forget about all the painful things in university and also provide you with a great chance to meet more people in different careers and a new, special horizon to think about the world.

(CHN_PTJ0_350_B1_2)

2) Many of them tell me that they have made a lot of new friends through their part-time jobs, …

(ENS_PTJ0_044_)

3) At the same time, gaining some working experience and sharpening their skills before graduating can be helpful in this competitive society.

(CHN_PTJ0_261_B1_2)

4) At first, I had the same plan as they did but as time went on I found I was losing interest in studying and always tired. (ENS_PTJ0_004)

5) So a part-time job is not necessary, of course except the guys who are really in bad conditions.

(CHN_PTJ0_370_B1)

6) The bad part of this is that it will place unnecessary stress on students who are already buried with schoolwork, and as a result of their actual educational experience may be negatively affected.

(ENS_PTJ0_036_)

7) The employer feels that if a student is focused only on school, and excels, they may be a poor candidate for employment.

(ENS_PTJ0_083)

8) …, it is a good choice for the college students especially someone who is from a poor family to take part-time jobs.

(CHN_PTJ0_364_B1_2)

9) It gives college students a chance to experience the world which helps them be ready for the future, it also provides a platform to let students show their abilities…

(CHN_PTJ0_294_B1)

10) I am not ready to work at a real company yet, and right now my job as a waitress is good enough for me.

(ENS_PTJ0_041)

11) Students must be able to focus on their studies and they should weigh carefully the impact of extra-curricular activities on their academic performance.

(ENS_PTJ0_090_).

12) In a nutshell, it isn’t a yes-no question but a complex phenomenon that reveals a lot of potential problems of our mode of college education.

(CHN_PTJ0_345_B1)

As it is presented in Table 8, the Chinese EFL beginner learners have many over-used adjectives comparing with the native speakers, including “important”, “good”, “poor”, “useful”, “necessary”, “independent”, “present” and “practical”, among which the most significant over-used adjective is “useful” at level A2. With an LL value of 19.94, it appears 9 times in the beginners’ writings while 0 time in the native ones. The second most underused word is “local” oat level B2, with a LL value of 17.64, which appears 22 times in the native sub corpus and 0 time in the beginner one. The third over-used word is “practical” at level C1, which has an observed frequency of 10 times at the beginner level learners’ writings and only 1 time at the native ones. The LL value of under-used adjectives are also of high significance, among which the most under-used one is “local”, with a LL value of 17.64, it is used 22 times by the native speakers but 0 times by the beginner writers. The result indicates that the beginner learners tend to use different adjectives with the native speakers under the similar writing conditions such as topic and length.

The following sentences are excerpted from the native and non-native writing samples in the ICNALE, and each one contains the over/under-used adjectives, which are shown in bold italics.

1) For modern college students, it is useful to have a part-time job.

(CHN_PTJ0_134_A2_0)

2) … part-time jobs can get the students out of the ivory tower and give them the opportunity to get along with different kinds of people, get useful working experiences and learn the value of labor.

(CHN_PTJ0_216_A2_0)

3) … before I began my master degree, I found a first job at a local restaurant.

(ENS_PTJ0_068_XX_1)

4) As far as I’m concerned, doing part-time jobs is not only important but necessary for college students.

(CHN_PTJ0_097_A2_0)

5) … so I think it is not really necessary for college students to be working.

(ENS_PTJ0_011)

6) Having a part-time job also allows you to appear more responsible to adults, and they will respect what you are saying more if you show them that you understand at least a bit about the real world.

(ENS_PTJ0_024)

7) …getting a part-time job is a good way to learn more about the real society earlier.

(CHN_PTJ0_064_A2)

8) This will make you more employable and develop practical skills outside the classroom.

(CHN_PTJ0_188_A2_0)

9) Secondly, having a part-time job allows students to develop practical skills…

(ENS_PTJ0_089_XX_1)

10) It enables him to be independent and builds up his self-confidence.

(CHN_PTJ0_216_A2)

11) In New Zealand, it is common for teenagers after graduating from high school and going onto university to move out of the family home and to spread their wings and become independent.

(ENS_PTJ0_085)

12) As a present university student, personally, I think university students should do some part-time job.

(CHN_PTJ0_323_A2)

13) Disrupting this involving relationship with academic study by saddling …, by interfering with the ceaseless cogitation that is a student’s meet and proper burden with all institutions of high learning, …

(ENS_PTJ0_100)

14) There are many advantages for students to have a proper part-time job. (CHN_PTJ0_198_A2)

The result of the overall over-used and under-used adjectives reveals that compared with the native speakers, the Chinese EFL writers tend to adopt general and vague expressions such as “it is good to…” and “it is important to…”. Moreover, the Chinese EFL learners’ writing excerpts show many inappropriate uses of the adjectives, for example, the adjective “proper” is misused in the sentence “there are many advantages for students to have a proper part-time job” (CHN_PTJ0_198_A2); and “present” in “as a present university student, personally, I think university students should do some part-time job” (CHN_PTJ0_323_A2). In terms of using attributive/descriptive adjectives, the result conforms with the previous finding that there are no significant differences between Chinese EFL learners and native speakers (Hinkel, 2002).

5. Conclusion

The study explores the differences in using adjectives between native academic writers and Chinese EFL academic writers at beginner and intermediate levels, which is investigated using a quantitative analysis method with the research data taken from three sub-written corpora of ICNALE, namely, the written corpus of native speakers and the written corpus of Chinese EFL learners at A2_0 and B1_2 level. The study results are presented in two aspects, namely, the overall frequencies of the three sub-written corpora and the specific overused and underused wordings. This section includes the evaluation of research questions, the pedagogical implications and suggestions for further research.

5.1. Evaluation of Research Questions

The first research question is to find out whether Chinese EFL academic writers and native academic English writers significantly differ with reference to the use of adjectives, and the findings indicate that the native academic English writers use much more beginner and intermediate level adjectives than their Chinese EFL counterparts, which is validated by the results of statistical analysis (p < 0.05).

The second research question is whether Chinese EFL academic writers of different language levels significantly differ with reference to the use of adjectives, and the results reveal that the Chinese EFL intermediate level academic writers are capable of using higher leveled adjectives in a broader range when compared with the beginner level learners with the confirmation of the statistical analysis (p < 0.05), which is a major marker in many standard English writing tests.

Besides, the result of the overall over-used and under-used adjectives reveals that compared with the native speakers, the Chinese EFL writers tend to adopt general and vague expressions; moreover, their writing excerpts show many inappropriate uses of the adjectives.

Study reveals that compared with the native speakers, the Chinese EFL writers employ adjectives that are vaguer and general. More importantly, the Chinese EFL learners’ lexical accuracy needs to be improved, as the results of the specific wordings show that some adjectives are used inappropriately in the writing excerpts. In terms of lexical richness, the native speakers don’t show a significant variation in using adjectives, as the frequency results reveal that the most frequent adjectives adopted by the native speakers are at level A2 and C1, which differs from the findings of previous studies, and the reason could be that the writing samples of the native speakers are not qualified representatives of academic writing style; or the lexical variety is limited by the settled topic. The result of using attributive adjectives subject to the previous research in that there is no significant difference between native speakers and Chinese EFL learners. The comparison between the beginner and intermediate Chinese EFL learners shows that the intermediate writers employ a wider range of higher leveled vocabulary, which is a major marker in many standard English writing tests.

5.2. Pedagogical Implications

Seeing on the research results above, it is of necessity for EFL/ESL teachers to attach importance to learners’ vocabulary extension and vocabulary accuracy. The former term refers to using sufficient low-frequency words that are appropriate to the writing topic and style (Read, 2000), and the latter means precise use of the wordings in the context.

As Jordan (1997) states, lexical variety and lexical accuracy should be highly valued in the teaching of EFL/ESL academic writings as the lack of both always leads to the reduction of test scores. That is why the writing band descriptions of the IELTS (The International English Language Testing System) attach importance to the wide vocabulary richness and variety by setting “using a wide range of vocabulary with very natural and sophisticated control of lexical features.

1) On expanding vocabulary

Hinkel (2002) suggests employing a “focused instruction”, where students are taught with the most essential adjectives in academic writings, such as new academic word list (Coxhead, 2000) (see appendix Headwords of the Word Families in Academic Word List), which contains 570 word families that account for around 10.0% of the total words in academic texts collected from academic journals, university textbooks as well as academic written English copra, and is designed to show learners with the words that are “most worth studying” (Coxhead, 2000).

2) On improving lexical accuracy

As N ation (2001) states, words are not isolated units, they are interconnected with other syntactic and grammatical systems. Hence, acquisition of the form of the most used adjectives alone does not necessarily increase the EFL learners’ academic writing proficiency, it has to be learned under certain syntactic and grammatical contexts. (Nation, Clarke, & Snowling, 2002) proposes three aspects for knowing a word, namely, the form of the word, the meaning and the use. Each aspect contains several specific questions. For example, the category of the use involves the questions like “in what pattern does the word occur?”; “what words or types of words occur with this one?” and “where, when and how often can we use this word?” The framework is typically useful instructions for classroom teachers to help students recognize the use of different adjectives.

5.3. Suggestions for Further Research

The research only conducts a comparison between English and Chinese EFL learners, therefore further research on other languages could be conducted; besides, due to the limitation in author’s time and energy, the research only examines the result of 200 English adjectives within 5600 writing samples, the further research might be conducted on a much broader scale of research corpus and research subject.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge support from the Project of Blended Teaching Reform of Zhejiang Yuexiu University (No. JGH2007).

Appendix

Headwords of the Word Families in Academic Word List

(Coxhead (2000) )Extracted