Exploring the Relationship between Work Engagement and Turnover Intention among Nurses in the Kingdom of Bahrain: A Cross-Sectional Study ()

1. Introduction

In the recent decades, shortage of healthcare workers has become a major attention across the world. In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) published the Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth report to lessen the loss of 18 million health workers. The report recommended the creation of 40 million new jobs for health and social care staff by 2030 [1]. The WHO projected the need of 9 million more nurses and midwives to grasp the Sustainable Development Goal number 3 on health and well-being by 2030; specially that 50% of global healthcare personnel consist of nurses and midwives [2].

In the advent of the current global pandemic, retentive actions for nurses and midwives should be kept at the utmost priority to maintain hospital operations, productivity, better quality outcomes to patient care, increased revenues, and enables the organization to further improve their services to the community. High nurse’s turnover rate does not only compromise quality of care, but also lead to economic loss [3]. Furthermore, it’s found that the estimated cost of nursing turnover from different divisions is around to $64,000 USD [4].

Turnover intention (TI) ranges between thoughts of leaving and the action of leaving and is considered the most important variable preceding actual turnover [5]. TI has been emphasized as an important predictor of voluntary turnover behavior. Multiple causal factors have been proposed as antecedents to it, including demographic characteristics, personal characteristics, and contextual characteristics [6]. Educational level, work status, marital status, the type of work, experience, and salary are reportedly related to TI [7]. A recent meta-analysis study done in Korea summarized the antecedents of TI in hospital settings and other industries; including but not limited to: work attitude, job strains, industry contexts, role stressors and coworker support [8].

Work engagement (WE) is defined as “a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” ( [9] p. 74). “Vigor” means high energy levels while working and assertiveness in the face of difficulties; “dedication” means being deeply engaged with sense of inspiration and pride; while “absorption” is being deeply immersed in work without sense of time passing [9]. Aboshaiqah and his colleagues justified the need of engaging nurses in their work to retain them; especially due to the fact that most nurses working in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) are expatriates and their recruitment is somewhat costly [10].

Studies have supported the relationship between WE and the nurses’ desire to leave the organization. For instance, Rafiq et al., support the negative association between WE with the TI, which means higher Engagement induces lower employees TI [11]. According to Saks [12], employees who are engaged, experience a reciprocation of positive interactions with the organization. They have a positive relationship with the employer; and hence are more intention to stay. To the best knowledge of the study authors, there is a lack of research on the nurse’s engagement and its relationship to TI in the Kingdom of Bahrain, which may demonstrate its significance to the national and international healthcare workforce.

Study questions

This study addressed the following questions:

1) What is the level of nurse’s work engagement and nurse’s turnover intention?

2) What is the relationship between selected demographic variables (namely gender and workplace division), and the level of employee engagement and turnover intention?

3) What is the magnitude of the relationship between the score of work engagement and the turnover intention among nurses?

2. Methods

2.1. Design, Sample and Setting

A cross-sectional descriptive correlational design was used to conduct this study. A “convenience sample” of 922 registered nurses from all units in a major 330 bedded tertiary hospital in the in the Kingdom of Bahrain was invited to participate in this study. The sample size needed for this study was computed using power analysis software. To obtain a power of 0.8, confidence interval of 95%, and estimated medium effect size, a sample size of 385 nurses is required for the study. The participants received an invitation sent through the hospital e-mail to fill an electronic self-administered survey along with the electronic consent form in December 2019. Nurses who have a work tenure in the hospital of less than 6 months, and those who are in a managerial position were excluded.

2.2. Data Collection and Ethical Consideration

Approval for this study was issued by The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at King Hamad University Hospital (KHUH) (ref. no. 20-314). Nurses were informed of the purpose of the study and had to acknowledge the electronic consent form before participating in the survey which ran from December 01, 2019 up to December 31, 2019. Respondents were assured that their participation will be kept voluntary and anonymous; all data will be kept in secured electronic files and that the data will be used only for research purposes. In total, 610 electronic questionnaires were completed with response rate of 66.2%. No missing data were found; one response was excluded due to a strange pattern of filling up the electronic survey form. The EQUATOR checklist (STROBE) was followed to write this manuscript.

2.3. Measures

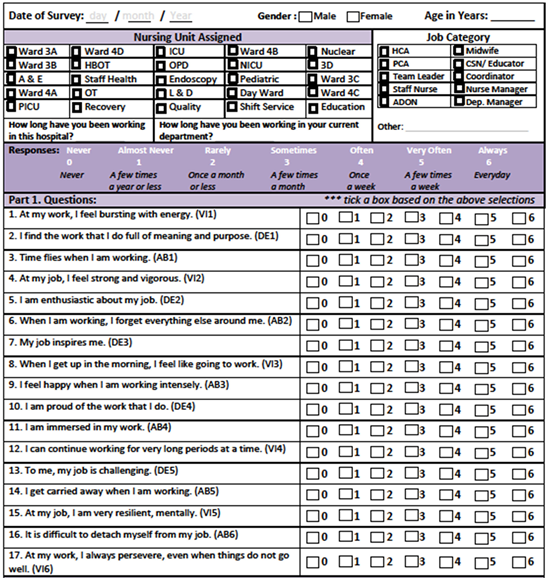

The questionnaire involved demographics that were developed by the main researcher based on the existing literature. The WE was assessed using the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) (Appendix 1). It is a valid and reliable instrument; with Cronbach alpha ranges between 0.91 and 0.96. The scale is composed of 17 items measure three subscales: “vigor (six items), dedication (five items), and absorption (six items)”. All items are scored on a seven-point Likert ranging from 0 answering “never” to 6 answering “always”. The Higher score on all three dimensions indicates higher WE. Cronbach alpha in this current study for this scale was 0.84. The (UWES) is free for use for non-commercial scientific research [13].

The 3-item TI Scale based on the Mobley et al. survey was used to assess the nurses’ TI [14]. The scale includes three self-reported items; First, often have the idea of leaving the organization. Second, want to seek employment elsewhere. Third, always want to leave the organization within a year. By asking the respondents to answer the degree to which they agree with the given three items, the TI level of the research objects is acquired. The scale is scored on a 5-level Likert scale with “1” representing “strongly disagree” and “5” representing “strongly agree”. The average score of all items reflects the overall TI. The higher the score is, the higher intention to quit from a job [14] [15]. The scale is reported to be valid and reliable [16]; with Cronbach alpha of 0.95 indicating the TI scale has good reliability [17]. Cronbach alpha in this current study for this scale was 0.82.

2.4. Data Analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 25 (SPSS 25) [18] was used to analyze data. Descriptive analysis was employed to describe the demographic data of the respondents. Composite scores of the UWES and the Turnover Intention Scale were obtained. T-test and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test were run to detect the differences between groups’ sociodemographic and the (TI and WE) variables. Pearson’s r was computed to determine the magnitude of the relationship between the WE and TI.

3. Results

The study sample composed of 609 participants. Majority of the study participants are females (72.9%). The age group 28 - 39 years formed 68.8% of the study sample. The participants work in four clinical divisions, critical Care (30.4%), in-patient units (37.4%), ambulatory services (24.6%), and perioperative services (7.6%). Most of the participants are Staff Nurses (81.9%), while the rest of the participants are team leaders and midwives. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics about the sample.

The total mean WE score using the (UWES) was [M = 4.85, SD ± 0.70]; The highest WE dimensions was Dedication [M = 5.40, SD ± 0.76], and the lowest WE dimension score was Vigor [M = 4.59, SD ± 0.85], while the Absorption dimension level was [M = 4.64, SD ± 0.85].

The total mean TI was [M = 2.29, SD ± 0.94]. Analysis of individual item percentage responses is presented in Figure 1; (we calculated the average number of positive responses (4 and 5) over the total number of items, the average number of negative responses (1 and 2) over the total number of items, responses at the midpoint kept as neutral)

An independent samples t-test was performed to assess whether mean TI and UWES differed significantly for group of male participants compared with female group participants.

The assumption of homogeneity of variance was assessed for both scales by the Levene’s test of homogeneity, F = 1.16, p = 0.28 for the TI scale; while F = 0.26, p = 0.61 for the WE that’s measured by UWES. This indicated no significant violation of the equal variance assumption; therefore, the pooled variances version of the t test was used.

![]()

Table 1. Frequency and percentage distribution of nurses according to sociodemographic characteristics (N = 609).

![]()

Figure 1. The percentage of turnover intention scale among nurses (N = 609).

The mean TI differed significantly, t (607) = 0.28, p = 0.001, two-tailed. Mean TI for the male group [M = 2.50, SD ± 0.98] was higher than mean TI for the female group [M = 2.23, SD ± 0.91].

There is no significant difference in the mean of UWES between male and female groups t (607) = 0.29, p = 0.77.

A one-way between-S ANOVA was done to compare the mean scores on TI and UWES scales with staff work in different clinical divisions (Group 1 = critical care, Group 2 = in-patient, Group 3 = ambulatory and Group 4 = peri-operative). Prior to the analysis, the Levene’s test for homogeneity of variance was used and no significant violation was found: F (3, 605) = 0.08, p = 0.97 for the UWES. And F (3, 605) = 1.10, p = 0.349 for the TI.

The overall F for the one-way ANOVA testing the difference between the unit’s division and the UWES was statistically significant, F (3, 605) = 3.44, p = 0.02.

In addition, all possible pairwise comparisons were made using the Tukey HSD test (using α = 0.05); it showed that the critical care and ambulatory divisions differed significantly; other groups were not significantly different from others. The mean UWES score for the ambulatory division [M = 5.00, SD ± 0.74] was significantly higher than the mean UWES score for the critical care division [M = 4.77, SD ± 0.69]. There is no significant difference in the mean of TI between groups by division F (3, 605) = 0.67, p = 0.572.

Pearson’s correlation was performed to assess whether the nurses’ WE level has a relationship with their TI. Table 2 shows negative correlation between the two scales (r = −0.325; p < 0.01).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate a relationship between nurses’ WE and TI among nurses in a tertiary hospital in the Kingdom of Bahrain. The study found a significant negative relationship between the staff WE and TI. This means higher levels of WE are associated with decreased TI. The

![]()

Table 2. Correlation measures of work engagement score and turnover intention (N = 609).

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). * (UWES) = Utrecht Work Engagement Scale.

nurses in the present study perceived a high level of WE to the hospital they are working in Bahrain as compared to other hospital in the (GCC) states [10]. Around two thirds of the participants reported low level of TI. Male staff have higher intention to leave, while those working in ambulatory division have higher WE than nurses working in critical care division.

The negative relationship between the WE and TI supports existing literature as numerous studies reported the negative relationship between WE and TI [11] [12] [19] [20].

There are various organizational factors that might have contributed to the high staff engagement score including favorable work environment, which is linked to higher engagement levels [21] [22]. Organization work environment factors like staff development, equal opportunities for training and promotion, safe staffing levels, and relaxed duty schedule with no mandatory overtime hours might play a crucial role in increasing the WE and lowering nursing staff intention to leave. Wan and his colleagues used a structural equation modelling to test a theoretical model of WE to address nursing shortage, the findings showed that work environment had a significant direct effect on TI and a significant indirect effect on TI via WE [23]. The competitive facilities provided for the staff like best accommodation and competitive scale salaries increase their satisfaction which found to be a mediator for staff engagement in several studies. Work resources, work characteristics and organizational support affect WE [24] [25]. Al-Nawafleh [26] supports that career advancement/professional education, salary, and benefits are major incentives for nurses to migrate to GCC region. Other factors include the adoption of transformational leadership style and decentralized decision making process that affect employee engagement which might influence their motivations [24] [27].

The TI was noted to be low when compared to a study conducted in GCC [28] and China [29]. The TI in the studied institution was lower than those reported by Chan Yin-Fah et al., [15] which used the same scale in a private sectors and investigating the difference in the TI of expats and non-expats. This could be related to higher satisfaction levels noted with most nurses working in gulf region [30]. Studies supported that low job satisfaction leads to intent to leave the workplace or the profession [31] [32]. Others studies support that high job satisfaction leads to low intention to leave [20] [29], In Bahrain, Ebrahim et al., [33] conclude the negative significant relationship between job satisfaction and TI among CCU nurses. Work environment and job satisfaction also linked to the intent to stay in work among nurses [34]. Furthermore, strong work support leads to lower TI [3]. Nonetheless, contrary to our expectations, there is still a notable percentage of nurses in the study who intend to leave, with 14.4% being regarded high TI by the researchers.

The TI among male nurses noticed to be higher than the female nurses; this finding is consistent with other study [32], on the other hand, no significant difference between male and female groups in WE, Even though, these results differ from previous published study that found female nurses have a higher score in one of the engagement subscales [10].

Nurses in critical care areas experience moral distress level that is negatively correlated with their WE [35] which might explain the present study findings where nurses in critical care division have significantly lower WE than those working in the ambulatory division.

5. Study Limitations

The use of a self-report survey and cross-sectional design could be said to be a limiting factor for this study. The mentioned does not allow drawing a direct causal relation, therefore, longitudinal study would be beneficial. Furthermore, as the results are limited to one public hospital, the generalizability of this finding may be limited and may not be applicable to private hospitals.

6. Conclusions and Implications

Considerable attention should be made on the fact that intention to quit is the immediate antecedent of actual propensity to leave behavior [14]. Highlighting the relationship between the two variables will be considered as serious implications for workforce planning and key retention strategies for nurse managers. Highly engaged employees tend to enjoy their work environment and are likely to assure their loyalty to the organization, aside from improved patient care outcomes. Nowadays, increase demand on health care providers due to the current pandemic, force the nurse mangers to think of innovative measures to promote WE. Further researches are needed for identification and intensification of WE strategies and to examine the relationship between self-expressed TI and the actual nurse’s turnover rate.

This study provided empirical results about nurse staff turnover intention and its correlation to their work engagement. It’s paramount to focus on work engagement dimensions, and developing effective interventions to improve it, which eventually decreases nursing staff’s turnover intention. Retention is preferable than recruiting, employing, and training new staff.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for all the nursing managers, team leaders and nurses who generously shared their time, for the purpose of this study.

Authors’ Contribution

Francis Opinion conceived the study, participated in its design, collected the data, and drafted the manuscript. Dr. Fairouz Alhourani wrote the discussion section and edited the final draft. Maha Mihdawi and Dr. Tareq Afaneh conducted the statistical analysis, wrote the results section, and provided substantial contribution in editing drafts of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript to be published.

Appendix 1: Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES)