Assessment of Psychological Distress among Parents of Children with Cancer ()

1. Introduction

Childhood cancer is relatively rare and accounts for only 1 to 3% of cancers in children under the age of 15 [1].

It is the second leading cause of death for children above the age of 3 years, after a mortal accident [2].

Significant biomedical advances over the past several decades have increased the survival rate for children with cancer to over 70% (SEER 2007).

However, improved prognosis and survival require prolonged, complicated, and intensive treatment protocols specially the chemotherapy and also radiotherapy, surgery and bone marrow transplantation. These procedures and the many side effects of treatment, impact quality of life not only for the child with cancer, but also for the whole family [3].

When a child is diagnosed with cancer a process known as psychological stress starts which interferes with the family daily’s life for a long period of time [4].

The family adaptation to this diagnosis, its treatment and its prognosis has been the focus of some scientific research in the last years [3].

In addition, the data in the literature in terms of the mental health of parents of children with cancer is contradictory and inconclusive. Some studies report the absence of risk of additional psychological damage [5]. However, the majority of studies report worsening symptoms of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder compared to the general population [6]. These studies also identified several risk factors for the development of psychological disorders in parents of children with cancer.

Moreover, this subject remains little studied in our Tunisian context. This is why we deemed it appropriate to carry out this study to describe the prevalence and type of psychological problems faced by parents of children recently diagnosed with cancer and to identify the risk factors inducing these disorders among these parents.

2. Ethical Authorization

The verbal and informed consent of the parents was obtained before the questionnaire and after a detailed clarification of the objectives of the study and its conduct.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Patients

This is a descriptive study carried out on parents of children diagnosed with cancer in the department of medical oncology at the Habib Bourguiba Hospital in Tunisia over a period of four months, from the beginning of December 2020 until the end of March 2021. Given the absence of studies addressing this subject in Tunisia, we conducted this preliminary study that we will be the basis for a further study of a larger sample by estimating the number of subjects required.

We interrogate the parents of children aged less than 18 years old who are undergoing curative or palliative treatment and we excluded the parents of children who refused to be part of the study.

3.2. Methods

The parents were interviewed during the hospitalization of their children.

We have collected primary the data about sociodemographic status of the parents and the clinical information about the child in particular the age, the gender, the date of diagnosis, the type of cancer, clinical and histological stage and the treatment options and secondary we have carried a psychometric assessment using various tools:

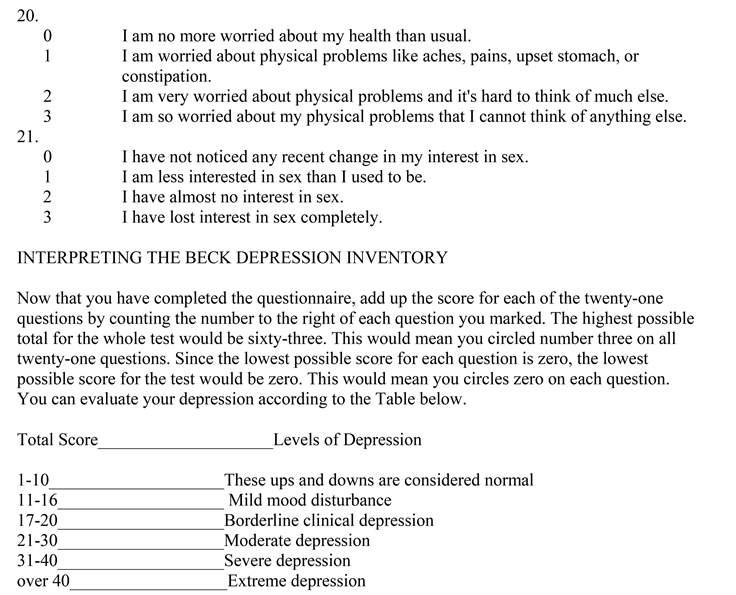

- The Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R):

IES-R is the most widely used instrument for the assessment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and acute stress disorder (ASD). [5] The authors currently choose to take a total score above 22 less than one month after the event as being in favor of significant symptoms of acute stress and a score above 36 more than one month after the event as suggesting the presence of post-traumatic stress disorder.

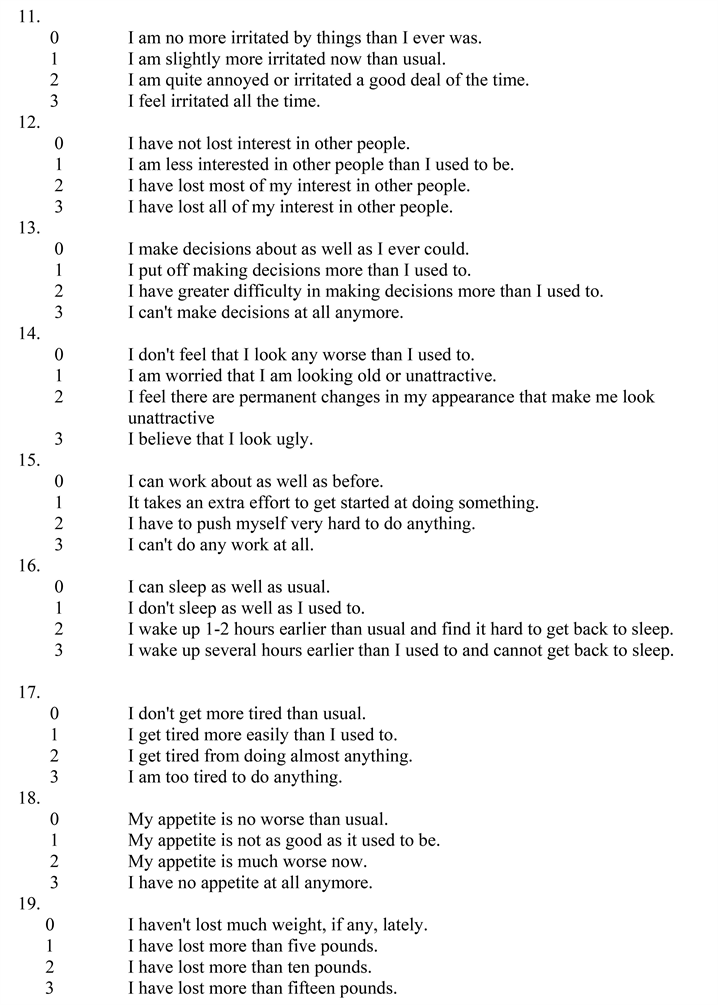

- The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI):

BDI is designed to assess the subjective aspects of depression: it is a subjective measure of depression, initially consisting of 21 items, the form of which was reduced by the original author to 13 items. The inventory measures depressive thinking’s by providing, for each item, a series of four statements representing increasing degrees of symptoms. For each item, the score ranges from zero to three. The higher the global score, the more depressed the subject is (0 to 39). It alerts the clinician, who uses the different severity levels, to the diagnosis of depression from a score of four and to judge the intensity of this depression:

- 0 to 3: no depression.

- 4 to 7: minor depression.

- 8 to 15: moderate to severe depression.

- 16 and over: severe depression.

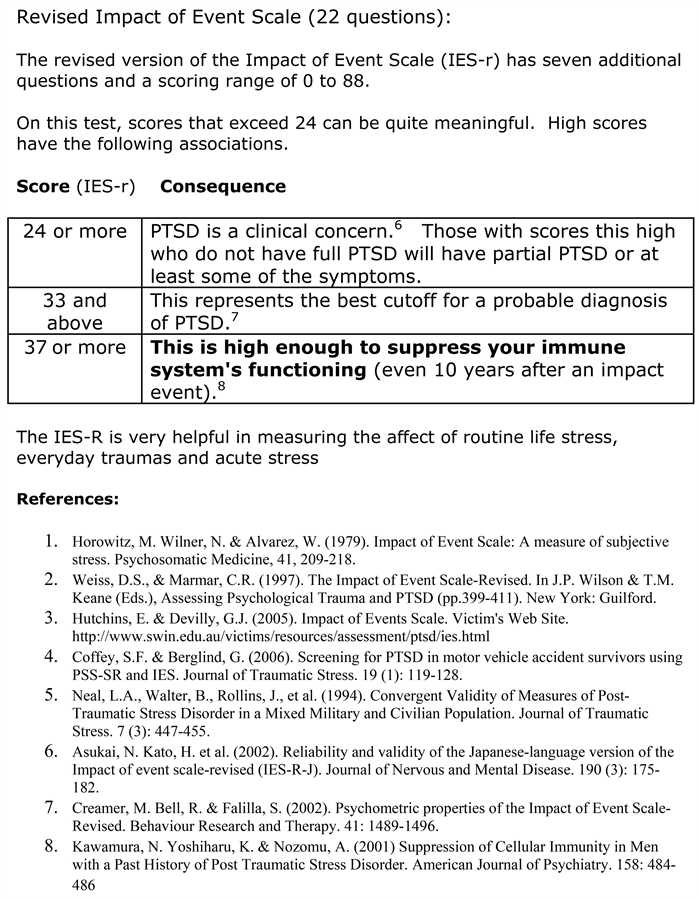

- The Hamilton anxiety rating scale (HAM):

Is one of the first rating scales developed to measure the severity of anxiety symptoms. The scale consists of 14 items, each defined by a series of symptoms, and measures both psychic anxiety (mental agitation and psychological distress) and somatic anxiety (physical complaints related to anxiety). Although the HAM-A remains widely used as an outcome measure in clinical trials, it has been criticized for its sometimes poor ability to discriminate between anxiolytic and antidepressant effects, and somatic anxiety versus somatic side effects. Despite this, the reported levels of inter-rater reliability for the scale appear to be acceptable [6].

3.3. Statistical Assessment

Data input and statistical treatment was done with SPSS software Version 20. To identify the relationship between the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the parents and the psychological disorder we have used the correlation test which concludes the significance when the p is <0.05.

4. Results

This is a descriptive trial carried out on 43 parents of children with cancer undergoing treatment at the medical oncological department of the Habib Bourguiba Hospital in Tunisia over a period of four months.

4.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

Table 1 illustrates the socio-demographic characteristics of the study population (age, sex, and marital status, and geographic origin, level of scholarity, professional activity, and number of children).

As for the clinical characteristics of the study population and their children, Table 2 illustrates their different features.

4.2. The Psychiatric Assessment

According to the IESR-R score, 37% of the parents had scores in favor of significant symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. Sixteen percent of the parents assessed before one month had acute stress and 21% of the parents assessed after one month had post-traumatic stress. The majority of parents have scores not suggestive of post-traumatic stress disorder (63%).

Then, according to the BDI depression score, 87% of the parents had minor to severe depression of which: 34% had minor depression, 46% had moderate depression and 7% of the parents had severe depression only 14% had a BDI score that did not suggest depression.

For the psychiatric assessment of anxiety, it was according to the Hamilton test and it showed minor anxiety in 34% of the parents and major anxiety in 61% of the parents. Only 5% of the parents had scores that did not suggest anxiety.

Table 3 illustrates the psychiatric assessment using different scores.

![]()

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the study population.

![]()

Table 2. The clinical characteristics of the study population and their children.

4.3. Correlation between Psychiatric Assessment and Clinical and the Sociodemographic Parameters Used in the Study

The analysis of the different socio-demographic and clinical factors that could be predictive of the occurrence of post-traumatic stress disorder in parents of children with cancer showed that only the female gender was a risk factor (p = 0.045 < 0.05). However, there was no significant relationship between the other factors and the occurrence of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Using the correlation test, our study did not show a significant association between the different parameters investigated and the occurrence of depression.

Among the socio-demographic parameters studied, only female gender was significantly correlated with anxiety levels in our parents (p = 0.006 < 0.05).

Significant correlations were also found between post-traumatic stress scores and symptoms of depression and anxiety (p = 0.04 and p = 0.003 < 0.05).

Table 4 detailed the correlation between psychiatric assessment and some sociodemographic and clinical factors.

5. Discussion

Pediatric cancers are rare and heterogeneous diseases representing 1% to 3% of cancers. They are characterized by the heterogeneity of their primary site and histological type. The major progress in cure rates, from 25% before 1970 to more than 75% currently in developed countries, is the result of therapeutic advances, and the development of multi-center clinical trials [7].

In Tunisia, the incidence of childhood cancer is estimated at 400 new cases per year, i.e. 18/100,000 children under 15 years of age according to World Health Organization statistics [8].

The most common types of pediatric cancer are leukemia, brain cancers, lymphomas and solid tumors such as neuroblastoma and Wilms’ tumor [9].

In our study, the neuroblastoma is described as the most common tumor (28%) followed by nephroblastoma, which represent 22% of cases and after that follow the diagnostic of meduloblastoma and Ewing sarcoma each of which represents 16% of cases.

When parents are confronted with the diagnostic of cancer in their child, a process starts, involving the appraisal of the stressor, followed by strain, and stress reactions, or the manifestations of strain, which become manifest as uncertainty, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and PTSS.

These feelings are, especially identified at critical moments (initial diagnosis, treatment, but also relapses) [10].

Learning that one’s child has a life-threatening disease is a qualifying event for PTSD or PTSS [11]. Approximately 68% of mothers and 57% of fathers of children currently in treatment report PTSS in the moderate to severe range [12].

![]()

Table 4. Correlation between psychiatric assessment and some sociodemographic and clinical factors.

In our study, only 16% of parents report a PTSS.

Sub-clinical PTSS such as intrusive thoughts about cancer, physiological arousal at reminders, and avoidance of treatment-related events have been found to be even more prominent [13].

Acute stress disorders occur in the first month after the trauma event. Their criteria are based on intrusive symptoms (such as involuntary rememorize of the traumatic event, also known as reliving), negative mood, dissociative symptoms (such as second state) the avoidance and waking disorders (ranging from sleep disruption to hyper vigilance).

These disorders are often associated with concentration difficulties.

In the case of post-traumatic stress disorder, there are also cognitive alterations (such as forgetting of the features of the trauma) [14].

In our study, a 21% report a PTSD.

Table 5 illustrates the prevalence of stress in parents of children with cancer in the comparison with the results of the literature.

In our trial, the prevalence of acute stress is relatively high, about 37% of the parents (2% of the fathers against 35% of the mothers).

This prevalence of acute stress significantly exceeds that of parents of injured children, which is still the leading cause of pediatric mortality which does not exceed 25% [18].

This is due to the parents’ perception of cancer as a source of childhood suffering, pain (disease, treatment, medical procedures) and its high associations with death [19].

In our study, 21% of the parents assessed after one month of diagnosis had scores in favor of post-traumatic stress. These findings are comparable to those cited in the literature, particularly those of Dunn et al. [20] and McCarthy [17].

These results may be attributed also to the fact that the parents in our study were predominantly represented by mothers and, following the results of the literature, the prevalence of post-traumatic stress symptoms in mothers is 2.49 times higher than in fathers [15].

It is considered that the chronicity of the disease, both in term of treatment and possible relapse is probably the most important stressor [21].

The therapeutic procedure for the acute stress include the Cognitive-behavioral therapy, which is particularly efficient in the treatment of acute stress and the antidepressants, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which are sometimes prescribed to reduce the severity of PTSD symptoms.

![]()

Table 5. Prevalence of stress in parents of children with cancer in the literature.

Parents may show depressive symptoms in reaction to their child’s cancer diagnosis.

These symptoms may include: a depressed mood; persistent sorrow, anxiety or emptiness, feelings of hopelessness or pessimism, feelings of guilt or helplessness, tiredness or low energy, significant decrease in interest or pleasure, difficulty in concentration or in making decisions, agitation, insomnia or hypersomnia [14].

Our study showed a high prevalence of depression in parents of children with cancer. About 86% of our parents had mild to severe depression (67% of mothers and 19% of fathers). Our results indicate that about 7% of the parents had scores in favor of severe depression and 46% had scores in favor of moderate depression. These findings are similar to the results of previous studies including that of SK Al-Maliki in Iraq which found an estimated prevalence of 70.5% (77.2% among fathers and 57.1% among mothers) [22] and Battcharya K in India which found a prevalence of depression about 78.3% [23].

This prevalence was lower in the study by K. Dietrich in Germany, which found significant depression scores in about 42% of the parents [24]. These results were similar to those of Kostak’s study in Turkey which found depressive symptoms in about half of the mothers and one third of the fathers [25]. This difference may be due to the difference in the assessment tools employed and the delay after the announcement of the diagnosis [7].

Table 6 detailled the comparison between our results and the findings in the literature in terms of depression in parents of children with cancer.

The announcement of a child’s cancer is a difficult moment. The family lived in a world of confusion and anxiety where all the members take care obsessively with their unique child in order to heal his suffering and thus to decrease their distress and anxiety.

In our study, we found a significant increase in anxiety among parents of children with cancer after the diagnosis (95%) using HAM scale.

We found that the majority has major anxiety (61%) and 34% has minor anxiety.

Our results are similar to those of Lichtenthal, who assessed the need of parents of children with cancer for mental health support and reported that 85% of parents had high anxiety scores [27].

![]()

Table 6. Prevalence of depression in parents of children with cancer in the literature.

![]()

Table 7. Prevalence of anxiety in the parents of child with cancer in the literature.

Moreover Boman K found high levels of anxiety in two thirds of the parents [28]. Similarly, Dietrich K found 54% of the parents have the diagnostic of anxiety [24].

These findings differ from those observed by Dunn et al., Dahlquist LM where only 37% and 13% respectively of parents have scores in favor of anxiety.

Anxiety is variable over time; it most often occurs at the time of diagnosis and decreases over time. Parents of children newly diagnosed or in active therapy report more anxiety symptoms than parents of children not in treatment, in remission, or in relapse [29] [30] [31].

Parents of relapsed children show higher levels of anxiety than parents of survivors or dead children [32].

Most anxiety reactions in parents occur at the time of diagnosis, with predominance in mothers. It can persist even up to five years or more after diagnosis [33].

Table 7 illustrates the prevalence of anxiety in our trial in comparison with the findings in the literature.

In our study, among the socio-demographic factors, female sex of parents was correlated with a significant risk of stress and anxiety with a p < 0.05.

Our sample of mothers was large enough this is because we have found a significant correlation.

Our findings are similar to several trials reporting an increased risk of psychological distress in mothers [35].

Our study has certain limitations. One of these limitations is the number of fathers which is significantly underrepresented.

6. Conclusions

The diagnosis of pediatric cancer is a potentially traumatic event and a major source of psychological distress for parents.

The objective of our study was to evaluate the psychological distress in parents of children with cancer. Our results showed a high prevalence of anxiety and depressive disorders among parents of children diagnosed with cancer and a significant correlation between stress and anxiety with the female sex of parents.

Our results were similar to several studies although other risk factors for psychological distress in parents of children with cancer have been described in the literature.

These results suggest also that psychosocial support should be offered to parents of children diagnosed with cancer in order to optimize cancer management.

Appendix

Appendix 1. Impact of Events-Scale-Revised

Appendix 2. Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A)

Appendix 3. The Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI)