1. Introduction

Regional disparities in development have been the focus in many discussions on development issues in the developing world during the past four decades. Currently, Sri Lanka’s HDI value for 2019 was 0.782, which put the country in the high human development category, positioning it at 72 out of 189 countries and territories (UNDP, 2020). As a country, while the HDI value of Sri Lanka has increased from 0.629 to 0.782, during the period of 1990-2020, the life expectancy at birth has increased by 7.5 years and Gross National Income has increased by 229.4% during the last 30 years. Meantime, in common with other developing countries, the regional disparities of development have been an inherent and perpetuating development issue in Sri Lanka. The economic growth and modernization are skewed in favour of megalopolis core area in the Western Province of Sri Lanka due to numerous historical and geographical factors. The Colombo Megalopolis encompasses three districts in the Western Province viz., Colombo Gampaha and Kalutara. The remaining eight administrative provinces that are sub divided into 22 administrative Districts constitute the periphery. Figure 1 depicts the Provincial contribution of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and it clearly shows that the contribution of Western Province was 48.7% in 1998 and 41.2% in 2015. The Western Province has benefited from the concentration of infrastructure investment with the Colombo Port, Financial city, Bandaranaike International Airport better road networks than the rest of the country and more reliable power and water supply than the other regions of the country. Consequently, the regional development disparities of Sri Lanka have been continuously widening. This paper investigates and discloses the major reasons for widening the reginal disparities of development during the last 70 years of Sri Lanka.

The details in Table 1 show that the smallest province of Sri Lanka is Western and represents 5.7% of total land area and 41.2% of GDP. The data in Table 2 illustrated the contribution to GDP by manufacturing sector of Sri Lanka in 2002. The Western Province of Sri Lanka had been working as the main industrial hub of the country since independence in 1948, and it had been formed

![]()

Table 1. Relationship among population, Land area, and GDP by province.

Data sources: Source: Central Bank of Sri Lanka (2017).

![]()

Table 2. Distribution of GDP by manufacturing sector.

Sources: National planning department, Sri Lanka, 2002/Wanasinhe, 2002.

during the colonial period from 1505 to 1947. Even after the independence, Sri Lanka has continued the same economic strategies. Consequently, the western province has become the economic core and other provinces have developed as the periphery. According to the data, the core area of the county (Western Province) represents 72.4 percent of the manufacturing sector. 80% of the manufacturing industries and 88% of workers in the industries have been agglomerated in the Western Province (Wanasinghe, 2002). Manufacturing industry accounts nearly 35% of the western province GDP, while in most other provinces it is less than 10% in 2002.

Figure 2 shows the Employed populations by economic sectors and provinces in 2019 and it proves that the largest service sector and the smallest agriculture contribution is represented by the Western Province. This is also another cause

for widening the development gap between the regions and communities. The rural economy is more significant in all the peripheral provinces and depending on the government subsidies. specially, irrigation water and land rent of traditional farmers are mostly free and fertilizer subsidy has been continuing since 1970s. On the other hand, all the successive governments have motivated the private sector investment in manufacturing sector in the Western Province. Consequently, the Western province has become the core of the economy and development as well.

2. Methodology

This is an inductive study under mixed method. Both qualitative and quantitative data have been collected and provided evidences for regional development disparities of Sri Lanka. The study mainly depends on the secondary data and provides the results as evidences of some case studies in relevance to the regional development disparities of Sri Lanka. This article summarizes widely developed classic and modern literature on regional development in Sri Lanka.

In this literature-based study, selected reputed articles, books and reports have been considered. The Human development reports of Sri Lanka, Income and expenditure survey of Department of Census and statistics, Central Bank Reports of Sri Lanka, the policy agreements of political parties and implemented policy agreements of the successive governments, National Physical Plans of Sri Lanka, Population Census Reports and scholarly works of G. H. Peiris, M. M. Karunanayake, Mick Moore, have been scrutinized to make the conclusions.

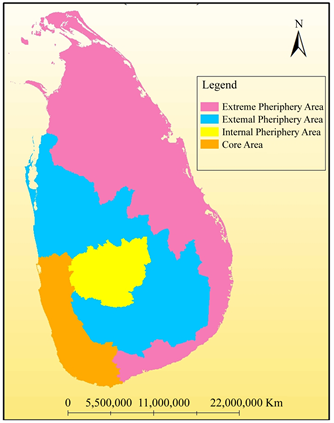

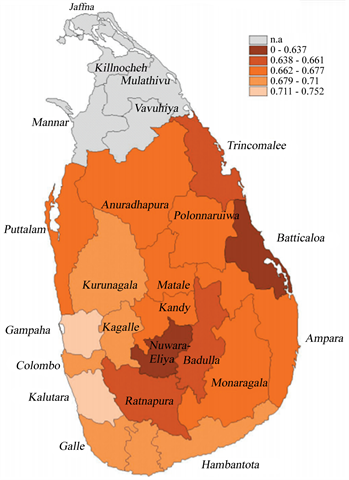

The main research problem of the study is about the major pertaining reasons of chronic regional development disparities in Sri Lanka even being achieved the high standards of Human Development Index (HDI). Map 1 shows the regional disparities of development in 1983 by Mick Moore and Map 2 shows the spatial pattern of HDI in 2012. Map 3 shows the regional development projects which are being implemented by the last and current successive governments of Sri Lanka covering all the provinces and the districts of the country. The main

Map 1. Distribution of core-periphery areas in Sri Lanka by Mick Moore in 1985.

Map 2. The Study area, Sri Lanka; Human Development Index 2011: Sub-National Variations. Note: This is the latest and the last updated HDI Report of Sri Lanka. Sources: Computations by the report team of the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka using Department of Census and Statistics of Sri Lanka 2010 and Central Bank of Sri Lanka 2011. Note: Regions with lighter colors have higher levels of human development; darker colors signify lower levels.

Map 3. Regional development project in Sri Lanka, since 2005.

argument brought out through this study is that the politically biased government policy programs and projects, racism, and nearsighted strategies, lack of monitoring and evaluation processes are the main reasons of the chronic regional development disparities in Sri Lanka.

The Rural Periphery in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka can be basically considered as a rural community where more than 70 percent population depends on agriculture sector. Although there are similarities of basic elements, there are diversities among different regional subsistence of rural sector. In spite of some rural areas have been directly integrated with modern urban sector, there are villages which are being isolated marginalized and deprived from the mainstream of development. As a response to this peripheral condition, increasing censuses for poverty alleviation on rural development has been a trend in the development policy of the country. There are volumes of literature not only on the basic issues and underlying causes at rural development, but also on the experiences of different countries including Sri Lanka.

The rural sector has at times been identified and distinguished from the urban sector in terms of its institutional characteristics by Weitz (1971), Dias and Silva (1981) and Wijedasa (2001). The urban sector has been defined to include those areas that come under the jurisdiction of the municipal council and urban councils. Except the above council areas and large-scale estates, all the other areas have been classified as rural.

Though, most of the people are engaged in agriculture for their livelihood the rural sector also includes some craftsmen engaged either full-time or part-time in small industries, trades and other different services. The term “rural” has been used in the present study according to these clarifications.

According to the data in Table 3, there is a significant development gap between rural and urban areas of Sri Lanka between 1980 and 2002. This view through based mainly on the Consumer Finances Surveys (CFS) can be seen a significant gap between rural and urban sectors. This situation is reiterated in previous CFS conducted in 1953, 1963 and 1973. Wages, and other impacts of various equity-oriented reforms (Lee, 1977) , and have thus found general acceptance. The subject of income distribution trends from the early 1970s to the early 1980s have, however been controversial. What may be regarded as the view to which most critics explicitly subscribe is that there was a significant growth of disparities since the 1973 (Peiris, 2006) . It has, for instance, been pointed out that while in 1973 the average income of the highest income decile was 16 times more than that of the lowest decile, by 1978/79 this ratio had increased to 33 times, and by 1981/82 to 36 times. A careful examination of the various viewpoints on this issue suggests that, while the notion of widening income differences between the rich and the poor which followed closely on the heels of “liberalization” cannot be discounted, a fairly large share of the increase in the disparities reflected in the CFS data in Table 5 should be attributed to the mutual incompatibility of the different data sets than to genuine changes in household incomes between urban and rural areas. According to the data in the table, average monthly income per person and the household have increased. However, the figures of percentage of income received by poorest 40 per cent of households to total income show the differences of the income gap between rich and poor.

The data in Table 4 show the changes of the percentage of poverty head count and poverty gap ratios from 1980s to 2002. These data emphasize the poverty gap between urban and rural population. Within the last two decades, percentage of poverty headcount has declined from 30.7 to 24.7. Percentage of the poverty gap ratio has declined from 8.9 to 5.6. This situation clearly emphasizes the

![]()

Table 3. Income distribution in Sri Lanka; 1980-2002.

Sources: Household income and expenditure survey reports, 1981/82, 1995/96, 2002 Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka.

![]()

Table 4. Poverty headcount and poverty gap ratios, mid-1980s to 2002.

Source: Peiris, G.H. (2006) Sri Lanka: Challenges of the New Millennium, Kandy Books, Kandy p.195. The source of the data for 2002 is a compilation by the Department of Census and Statistics titled “Statistics on Poverty Trends in Sri Lanka (2005)”.

insufficient change of the village economies. Poverty head count ratio of the country is 4.1% in 2020, and problem is the regional variations of the poverty. The lowest rate of poverty head count has reported in Colombo (0.6%) while Mulativu (11.2%), and Killinochchi (15.0%) districts have recorded the highest rates of poverty head count of Sri Lanka.

3. Results of the Study

The regional development disparities depict in different ways in Sri Lanka. According to the study, rural-urban development gap is the major problem in the country, and this gap has been widening continually. The development inequalities between the provinces and districts are one of the major development issues in the country for many decades and it is also widening. Consequently, the different types of negative results have been emerging at different levels and they also contributed to widening the gaps. All the successive governments of Sri Lanka have addressed the issues and this section of the article analysis the selected strategies of governments to reduce the development gaps between the regions and communities.

3.1. Rural-Urban Development Gap

Among the scholarly works on rural change in Sri Lanka, there are different perspectives and approaches followed by social scientists. A socio-economic survey in an Up-country village of Patha Dumbara revealed the process of disintegration of traditional village economy mainly through fragmentation of land holdings (Sarkar & Tambiah 1957) . Traditional land inheritance practices, scarcity of land and increase pressure of population has been accountable for this situation. Farmer (1957) also emphasized that the rural community of upcountry did not enjoy high living conditions. The World Bank (2014) discovers the accessibility of rural areas of Sri Lanka is still significant. Due to the poor road conditions, the infant mortality rate is higher and poor school attendance and school drop-out rate are also higher than the urban areas.

Some segment of the community was pride of cultural behavior and harmony, but the majority showed backwardness, low level of education and unsatisfactory health condition were stamped. Sociologist like, Ryan (1958), Leach (1961), Yalman (1967) and Obeysekara (1967) have attempted to identify the social structural pattern (caste, kinship and land tenure), Social organization, and Politics in the rural areas of Sri Lanka (Karunathilake, 2004) .

In 1958, Bryce Ryan researched on secularization and its pattern and process in Sinhalese village of Pelpola in Kalutara District. He has mentioned that the traditions and the beliefs of the villagers affect to slowdown the social development. As a result, village economy, technology marketing and their livelihood pattern were changing very slowly. These things really impact on the social development of a village.

Obeysekara (1967) argues that there is a close relationship between the land tenure and size of land of the villagers and their socio-economic condition. He gave a good example from Madagama, which is in the northern tip of the Southern Province of Sri Lanka. According to the population growth in the family and the village, the lands have been divided among family members. Through generations, it has created many of social and economic problems in the villages because, the land-man ratio has gone down, and the fertility of the land and the income also has decreased. The land tenure and the size of the owned land have affected the development of backwardness in rural areas of Sri Lanka.

Theodor von Fellenberg has done a research to identify the process of dynamics in rural Sri Lanka with special reference to a Kandyan Sinhala villge (Higgoda) in 1966. As explained by Figure 3, the exogenous impulses created the main theme of the village study, forced by a deteriorating man-land ratio, changed from a traditional way of living to a transitional plural society. Fellenberg has mentioned that the process of dynamics in Higgoda received its main impulses from the dynamic neighborhood first in an earlier period from the estate economy, and the national extension scheme of the government (See Figure 3).

![]()

Figure 3. The process of dynamics. Source: Fellenberg von Theodor (1966). The process of Dynamics in Rural Ceylon, with Special Reference to a Kandyan Village in Transition, Druck, A. E. Bruderer, Bern. p. 42.

Exogenous dynamics may be considered endogenous when Higgoda people took to innovations without compulsion or propaganda and even against resistance. The reaction of the villagers towards innovations has been generally positive if these were not against tradition or religious values. Absence of practical knowledge and lack of cheap credit were strong inhibitions, while the threatening land scarcity, free government aid the rising level of felt needs is incentives for dynamics. The assimilation of the new practices required a long period of time and a strong leadership.

Under the new commercial agricultural system, land became a marketing good, the growth of infrastructure facilities introduced the new institutional system of commercialization of the economy, Growth of financial exchanges, new system of law, growth of new cities, the migration patterns had influenced the creation of the backward and prosperous areas in Sri Lanka under the colonial period (Roberts & Wikramarathne, 1973) . They especially mentioned that these factors really caused the development backwardness in Up-country.

Dias and Silva (1981) mentioned several failures of rural development in Sri Lanka. They give evidence from Kalutara district in Sri Lanka. The failure of the development policies to generate rural development could be attributed to the lack of a clear policy or ideology of rural development that could have formed a framework or model for rural development. According to them the communication gap between people and the government has increased the development gap between rural and urban. The institutional hierarchy and the services also have affected to enhance the underdevelopment of rural areas of Sri Lanka. They emphasized the necessity of alternative development strategies and methodologies to advance the living quality of the people in rural areas.

Wijedasa (2001) has explained the factors that have affected the development backwardness in the hillcountry especially the villages of Poddalgoda (Kandy District), Raitalawa (Matale District), Harasbedda and Madulla (Nuwara-Eliya District) and Matigahatenna (Badulla District). Unequal growth of infrastructural facilities in colonial period, traditions and attitudes against modernization, High competition of education and economic opportunities, Traditional agriculture, and physical landscape issues are the main factors that affected the backwardness of the study areas.

Perera (1984) who discussed the relationship between social change and rural development in Sri Lanka, explains the concepts of “social change” “modernization” and “incorporation” refer as three interrelated social process. According to him two distinct processes, as the penetration of the state into rural areas, and the politicization of rural masses, can be regarded as interrelated processes of incorporation. Although Sri Lankan villages had never been isolated entities, it was reasonable to believe that they stayed relatively unchanged until the turn of 20th century. In 2020, the proportion of the population with access to electricity of Sri Lanka is 97.5%. The gap between rural and urban is not significant. The positive changes in the distribution of economic benefits and of life chances in general have been a by-product of changes in the political sphere primarily.

The importance of the political process as the prime mover of social and economic change in the rural sector has also resulted in a change in the status of the peasant from a producer of agricultural surplus to a politically manipulative income. This has also contributed to the emergence of a new dimension of social stratification in Sinhalese rural society and is seen in terms of the dominance of regional political elites in village affairs. It goes without saying that with the acceleration of the political influence of the state, the village has also lost its importance as a unit of social and economic action (Perera, 1984). According to Morrison et al., the basis of rural economy in ancient Sri Lanka was traditional and intensive subsistence paddy cultivation, and the culture and the other related rural livelihoods were closely integrated with the system of paddy production.

According to them, the long run effect of the opening of the plantations on the village was equally disruptive. The accompaniments of plantation were better roads, English education, a money economy, and a modern form of government, which provided health services to the people. The death rate was reduced and the population in the rural areas increased. The colonial system did not provide much scope for the expansion of employment. This situation was made worse by the destruction of cottage and rural industries, which followed the importation of cheap foreign goods.

Karunanayake and Narman (2002) attempts to provide some preliminary remarks on the manner in which political forces acting on ecological processes that contribute to create and perpetuate poverty in rural Sri Lanka. It explores the relationship between political ecology and rural poverty with reference to forest management and management of Wildlife Reserves, in Sri Lanka. He emphasized that some of the conservation strategies do not provide choices and opportunities for the rural poor to sustain their livelihood. Hence, the political ecology of protected area management and the way it impacts on the rural poor are ultimately tied up with the larger issues that concern the Sri Lankan policy.

Ryan (1958) and Jabbar (2005) have attempted to explain whether there is a caste dimension to poverty in Sinhalese society. The higher and lower castes, a large percentage of people have no evidence to suggest that open discrimination against the lower castes has almost disappeared. However, the popular view that caste no longer matters in Sinhalese society may not be accurate when considering the condition of the lower caste poor.

Jabbar (2005) has examined the relationship between caste and poverty in Districts of Kegalle and Kalutara. According to the study, most of the lower caste respondents were also of a lower socio-economic status and they continue to experience difficulties in accessing employment opportunities, with a substantial number still engaged in low status jobs. The low caste villagers feel that their class is partly to blame for their inability to move out of poverty and speak of discrimination in accessing employment as well as the education system. Caste may matter more or less depending on one’s caste position in the hierarchy and weather one lives in rural areas, but the findings of their study indicate that if one is poor, being from a lower caste is an added obstacle to overcome poverty.

Chandrasena (1981) has analyzed the inter-area transactions and income flow of village economies from Moragala and Kaluagala in Kalutara district. He proved that a village area is a viable unit for analyzing rural economies to identify villagers’ problems. Low inter household flows of resources do not make a significant impact of income flows into villages on the income structure within the villages, similarly low rate of multiplier effects are major causes for slow economic growth. The main problem in the villages is the accessibility. Still, this situation really disturbs the dynamism of the villagers.

The deployment, on an immense scale of resources, technology, skills, and expertise, from the urban to the rural sector, is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for the development of the rural productive forces. Equally necessary is a transformation of the economic relations within the framework of which these productive forces operate. The basic cause of rural economic backwardness is that these economic relations have become a fetter impeding the growth of the rural productive forces. They must accordingly be changed into relations which are conducive to faster growth.

Dangalle (2002) has mentioned that Sri Lanka was among the pioneer countries in Asia to attempt development planning with an emphasis on social development. The objectives of improving the standard of living of the people living in the periphery have been a major contributory factor to the adoption of this approach. According to Dangalle, even after more than half a century of development planning with two decades of intense region-specific development efforts, spatial imbalances in development have not disappeared. Giving an example from Hambantota district, he mentioned that to worsen the situation, the country is engulfed in an ethic conflict, which not only consumes a large amount of funds which could have otherwise been invested in development work, but also making it increasingly more difficult to implement development programs at a regional level specially in the North and East. Also, an ever-increasing unemployed labor force, a large majority of them well educated, creates frustration among the youth and their dissatisfaction has already been demonstrated in 1971 and 1989. In the context of globalization process on the other hand, and increasing the demand for localization on the other, it has been made clearer than ever before that regional development is an essential strategy.

There is a growing body of literature on post-conflict development throughout the developed and developing world. Sri Lanka also has been experiencing an ethnic issue during the last two decades. Any kind of war or conflict situation would directly disturb the development process of the country or area. Shanmugarathnam (2002) has pointed out that the ethnic issue of Sri Lanka has widened the regional development disparities. Most of Sri Lankans are facing increasing economic hardships and social insecurity. They are tired of the war as shown by the popular, spontaneous participation of hundreds of thousands of people in a recent campaign across the country against the war and for a negotiated settlement. However, the obstacles to a fair resolution of the national question are formidable indeed. They are a challenge to the forces that stand for peace, human dignity, and equitable development in Sri Lanka.

As mentioned in the first part of this chapter, there are many development strategies, which have been implemented to minimize the regional development disparities and enhance the living quality of the people. The IRDP and REAP strategies have been implemented under the patronage of the government. According to Karunanayake and Abhayarathna (2002) , the IRDPs had depended on low productive economic activities for employment and income generation. Unfortunately, the program did not permit the rural poor to go beyond the point of economic stagnation. It is crucial that REAP does not get caught in the same trap. The issue of the sectoral and spatial linkages is of crucial importance in promoting economic development on the lines envisaged by REAP.

About spatial linkages, it is necessary that REAP provides for an institutional arrangement that would facilitate cross-border planning in order to realize “comparative” and “competitive” advantages. The manner in which the REAP strategy relates to the poorest segments of rural society, who have hitherto been supported by IRDP social and welfare-oriented programs initiated by the IRDPs led to a reduction in the levels of human poverty in the rural peripheral areas. IRDP had not been able to make a significant dent in alleviating income poverty in the rural sector. Clearly the attempt in REAP is to bring about a change in the situation of the poor through the generalization of economic advancement (Karunanayake & Abhayarathna, 2002).

Peiris (2006) has also observed the factors and causes of rural backwardness in a study of Meedeniya Village Expansion Scheme in Kegalle district. According to the field investigations he has mentioned that the scheme needs to be reiterated. Conditions in the village are certainly not unique, although they could well be exceptional. He has emphasized that the village dwellers in village are poor and suffer many disadvantages; Yet the Meedeniya community, placed against the backdrop of the general conditions that prevail in the rural area in which the scheme in located, does not appear as one, which consists of social outcasts who suffer from the abject poverty.

Spatial zones of urbanization in the Gampaha district have been identified by Dangalle and Narman (2006). They mentioned, Negombo, Katana, Ja-Ela, Wattala and Kelaniya DSDs on the urban core of the district. Gampaha, Mahara and Biyagama DSDs have been identified as a peri-urban area.

Foregoing discussion clearly states that there are many complex factors that affect the socio-economic development and even after half a century of development planning, there remains considerable variation in the spatial distribution of economic and social development in Sri Lanka. It is well evident that considerable spatial imbalances exist in rural and regional development in Sri Lanka. As a result of urban biased development, the more developed and highly urbanized Colombo Metropolitan Region (CMR) that is approximate to the Western province of the island has emerged as the hub of gravity in the national economy.

Government of Sri Lanka unveiled a major reorganization of economic development. Among other reforms, the Government established several Regional Development Ministries to concentrate on the development of specifically identified contiguous areas of the country. The Ministry of Western Region Development (MWRL) was established to undertake this function in the Western Region. The Western Region covers the area of the politico administrative Western Province. The Region thus constitutes Colombo, Gampaha, and Kalutara Districts.

Examining the data and indexes that are presented in the tables and maps from 01 to 04, Gampaha District is the second most developed district in Sri Lanka, but two indicators have shown the underdeveloped situation in Gampaha District. Percentage of Income received by poorest 40% of household from total income of the District in Gampaha is 15.6%. Gini coefficient also shows (0.44) the District is therefore not in good position by the development standards. As a result of those conditions, Gampaha district has fallen into 8th place in the development rank. I think these indexes give an idea about the development disparities within the Gampaha District. Examining these development conditions, Gampaha District was selected as the study area of this research.

3.2. Economic Circuits in Rural areas in Sri Lanka

Hettige (1990) attempted to examine the relationship between the urban poor and the macro-urban system in the light of an empirical study of a community of urban poor in the city of Colombo. Hettige examined the position of the urban poor against the wide-ranging conceptual discussions that have taken place in recent years. As was also mentioned there, the subsistence activities in which the urban poor are engaged in reveal a wider system of exchange relations, which extends very much beyond the boundaries of the city. So, what Milton Santos called the “lower” and the “upper” circuits of the urban economy are by no means summoned to the city economy.

Hettige has examined how these urban-rural exchange relations can be discussed in terms of the conceptual classification of upper and lower circuits. In doing so, he argued that rural urban exchange relations can be visualized as taking place at two different levels, namely those of the upper and the lower circuits. The implication of the above argument is that the circulation process that links the village with the city and beyond is not simply dominated by large capitalist and state enterprises but gives way to a whole range of small entrepreneurs scattered throughout the country. This pattern has largely been the result of the nature of the urbanization process itself. It might, therefore, be useful to have a brief look at the urbanization process as it has unfolded in the Third World with reference to Sri Lanka.

Urbanization in the context of developed Western countries was a process that was closely associated with industrialization. Even though the lower strata of urban, society existed under appalling conditions during the early stages of industrialization in those countries, with technological advancement, increased productivity, social reforms and increasing international division of labor, conditions changed steadily and the disparities between the lower classes on the one hand and the more affluent strata of society on the other became increasingly narrowed.

Despite limited urban growth, Sri Lanka’s main urban center, Colombo, has not been able to accommodate all its inhabitants within the “formal urban economy”. In other words, a sizable segment of the urban population is dependent on informal income sources. So, the urban economy remained polarized between larger establishments, both public and private sectors are on the one hand and those small enterprises and activists on the other.

With the expansion of urban-based economic activities over the last decade or so due to the liberalization of the economy, not only the larger establishments have expanded their operations, but the informal urban economy has recorded a considerable increase in its activities as well. Since most of the new and expanded informal economic and, service activities are located in and around Colombo, the Colombo metropolitan Region which includes the district of Colombo as well as parts of the adjacent districts like Gampaha has attracted people from the other parts of the country. The resultant increased demand for consumer goods and services in the metropolitan region has created opportunities for informal activists engaged in tertiary activities such as personal services, retail trade, construction, and transport

An increase in economic activities in the metropolitan region has also meant an intensification of the flow of goods and services between the former and the rural hinterland. The concentration of a mass of wage-earning people in the metropolitan region has led to a rapid increase in the demand for food that is mostly produced in the rural areas. The resultant increased flow of goods attracted not only formally organized, larger establishments but, also informal activists. In other words, goods, continued to flow not only through the upper circuit but also through the lower circuit. However, before an attempt is made to examine the relative significance of the two circuits in the process of production circulation, a brief look at the nature of rural agrarian production seems to be in order.

In spite of significant changes in the composition of Sri Lanka’s GDP over the last few decades, rural agricultural production continues to be the largest sector in terms of employment and subsistence in the country The vast majority of rural producers are peasants engaged in the small holding sector for production of both food crops and cash crops. Given the fact that rural production units are mostly small-scale, those who operate the circulatory process related to such production also tend to be largely informal small-scale operators who either wholly or partly operate the chain of activities associated with the circulatory process. The actual composition of the actors depends to a large extent on the type of commodities produced and the nature of the production organization.

Nevertheless, it is possible to identify certain general patterns pertaining to the processes of production and circulation. As is well-known, rural economic production in countries like Sri Lanka takes place in both plantation and peasant settings. The division is not simply a distinction between two types of produce as the same commodity may be produced in both settings as cash crops such as tea, coconuts, and rubber. It is also true that almost exclusively the peasants produce certain commodities.

Many writers who have conducted research on urbanization in the underdeveloped countries have highlighted the fact that a typical Third World city consists of two inter-woven sub-systems in economic, social, and even cultural terms. Elsewhere, the author has discussed some of the concepts that have been introduced by different writers over the years in their attempts to grasp the complex empirical reality involved (Hettige, 1990) .

Upper circuit consists of banking export trade and industry, modern urban industry, trade and services, and wholesaling and trucking. The lower circuit is essentially made up of non-capital-intensive forms of manufacturing, non-modern services generally provided at the retail level and the non-modern and small-scale trade. What appears from the above description is that the two circuits have many parallels with the other conceptual distinctions made by other writers such as formal and informal economy, farm-centered and bazaar economy, capitalist production, and petty commodity production, etc. The flow of goods and services between the urban center and the rural economy is an equally complex process. Yet, it is not difficult to identify its main features in both empirical and conceptual terms. The following diagram is an attempt in this direction (Figure 4).

As indicated above, there are two channels through which goods and services flow between the urban center and the rural economy. The two channels are not mutually exclusive as a certain amount of goods and services moves from one channel to the other at different points, of the chain. The interchange of commodities takes place due to various reasons such as processing requirements and problems associated with collection and distribution. The interchange of commodities between channels does not always follow the same pattern (Figure 5). If we take commodity 1 (Cl), it leaves channel 2 into channel one again. In this movement of a commodity, the latter may go through a transformation or

![]()

Figure 4. Inter-linkages between rural and urban economies. Source: Hettige, S. T. (1990) “Upper and lower circuits in the context of urban-rural exchange relations” Sri Lanka, J. S. S. NARESA, p. 22.

![]()

Figure 5. Interchange of commodities between circuits. Hettige, S. T. (1990) “Upper and Lower Circuits in the Context of Urban-Rural Exchange Relations” Sri Lanka, J.S.S. NARESA, p. 23.

remain the same throughout its journey from one end to the other. Examples for the former are tea, tobacco (C1, C2, etc. = Commodity 1, 2, etc.).

The green tea leaves produced by the small holders reach modern, large factories either directly or through informal middlemen. Factory produced tea is transported to the urban center for bulk sale at public auctions. While a major part of it is purchased and exported by large trading firms, the rest is released to the local market. It is at this stage that part of the finished product enters the lower circuit and reaches the consumer through informal activists. When it goes through the Lower circuit, it may subject to certain minor changes such as blending and packaging.

In example for a commodity, this travels through the above channels, yet does not undergo a transformation. In underdeveloped economies like that of Sri Lanka, such perishable commodities go through the channels’ quickly and reach the consumers without being subjected to processing or packaging. A commodity like natural rubber, produced by both large planters and small producers, enters the formally organized, upper circuit, and remains there until it reaches consumers as finished products. On the other hand, certain commodities remain within the confines of the informal economy from production to consumption i.e. certain hand-made household utensils.

Since the flow of commodities between the city and the countryside is essentially a physical movement of goods, two decisive factors influencing the process are the distance and the nature of the means of transportation involved. Transportation of large quantities of goods between two points that are located far away from each other is beyond the means of those who do not possess heavy transport equipment such as trucks and lorries. On the other hand, short distance transportation of small quantities of goods is the prerogative of informal, small-scale operators. In this regard, it is also important to note that the type of commodity is also a major factor. A useful distinction can also be made between high value indivisible goods and low value divisible goods (Figure 6).

3.3. City of Colombo, the Circuits, and the Rural Hinterland

Colombo as the capital city of a developing country shares many features in common with most cities of the ex-colonial world. Its economy is polarized

![]()

Figure 6. Urban rural commodity flows. Hettige, S. T. (1990) “Upper and lower circuits in the context of urban-rural exchange relations” Sri Lanka, J. S. S. NARESA p. 24.

between modern, capital intensive production and service establishments on one hand and the informal urban economy on the other hand. Its social structure is characterized by a sharp distinction between the disadvantaged urban population concentrated in slums and shanties and the affluent social strata occupying the residential quarters of the city. In the absence of broad-based industrial production, most city dwellers are compelled to subsist on tertiary activities largely focused on the urban informal economy. This is a major factor reinforcing the parasitic nature of the city, which by and large generates its, wealth by playing the dominant role in the circulatory process linking the rural economy with its external environment, both national and international.

Given the fact that the economy of the city of Colombo is essentially an integral part of a wider system of production and circulation, any conceptual model dealing with it should encompass that wider system. This is the rationale for the extension of the analytical scope of the concepts of “upper” and “lower” circuits to deal with urban rural exchange relations. An empirical analysis of the city would also indicate the need for such a broad conceptual framework.

An analysis of the economic structure of the city, therefore, should also focus attention on the wider system of production and exchange relations because an understanding of the former is virtually impossible in isolation of the latter. Similarly, the urban informal economy cannot be meaningfully examined in isolation from its environment (Hettige, 1990) .

3.4. Evolution of Regional Development Strategies in Sri Lanka

It is quite evident that considerable spatial imbalances exist in rural and regional development in Sri Lanka. As a response to the diversity of physical features, the human activities vary by regions. Besides, there remain considerable variations in the spatial distribution of economic and social development in Sri Lanka.

During the second half of the 20th century, since Sri Lanka gained her independence in 1948, diverse strategies and approaches have been experimented to achieve development in the country. With some expectation of attaining a decent level of living for her people (Dangalle, 2002) . Depending on the political ideologies and policies of the successive governments in power and backed by the development thinking of the international community involved, these strategies and measures have been changed from time to time.

The measures adopted to ensure that the results of the development efforts in Sri Lanka would reach the people can be divided mainly into two types; namely administrative and developmental (Dangalle, 2002). Administrative system of the Sri Lanka has been revised as a requirement to minimize the regional disparities in the country from time to time. The major changes of the administrative system were the development strategy of the country. Even of power devolution in Sri Lanka is closely merged with regional development disparity. Tamil terrorist organizations including the LTTE have been emerging the regional disparities have caused the marginalization of the Tamil people. Most of political parties in the country suggest devolution of power to diminish the ethnic issues.

Even before the independence a decentralized administrative system was in operation in Sri Lanka to facilitate the central government in implementing its activities at the regional level. Under the Kachchery system, the country had been divided into districts. A Government Agent was appointed as the chief executive officer of each district. The district was divided into DRO divisions and later to Divisional Secretariat Division (DSD) headed by Assistant Government Agents. In turn, the DSD divisions also were divided into smaller divisions headed by village level officers. The main duty of these officers was to coordinate various sectoral programs implemented by the central government. The designations of all these officers representing the central government at the regional level were changed from time to time. The establishment of District Coordinating Committees and Divisional Coordinating Committee in 1954 at district and divisional levels respectively greatly facilitated the coordinating roles of these institutions. Also, with the introduction of the District Coordinating committees an attempt was made to recognize the principle of participation of people’s representatives in the coordination and review of District Development Plans.

The 1970s a chain of changes in the administrative system was introduced with a view to accelerating the implementation of development activities at sub national level. The establishment of the District Political Authority (DPA) system in 1973 was a significant step in the process of decentralization and politicization of the sub-national level development planning. Under the DPA system, a leading member of parliament of the ruling party headed the planning machinery of the district. In 1978, with the change of government, the DPA system was replaced by the District Ministry (DM) system, again, a dominant member of parliament of the ruling party was appointed as District Minister to head the development planning and implementation machinery in the district.

Another measure adopted to decentralize the development administration was the establishment of District Development Councils (DDC) through the DDC Act of 35A 1980. The DDC comprised all members of the parliament in the district. The establishment of Provincial Councils (PC) in 1987 with the 13th amendment to the constitution of Sri Lanka, although aimed mainly at solving the ethnic problem in the country, helped to further decentralize development activities. A Chief Minister heads the PC, comprising of elected members from the province. Four ministers appointed from the members assist the CM. In the PC, a governor appointed by the country’s president represents the central government.

Another institutional approach facilitated the development activities at regional and local levels were the local government structure. The present local government structure was first introduced in 1931 with the recommendations of the Donoughmore Commission and a hierarchy of local government institutions comprising of Municipal Councils, Urban Councils, Town Councils and Village Councils were established. These local bodies were comprised of people’s representatives and they were entrusted to plan and implement program aimed at providing the people’s basic utilities. All these attempts could be termed as peripheral administrative measures aimed at facilitating the implementation of the central government’s sectoral development programs and these were not region specific or aimed at eliminating spatial variations in development.

3.5. Land Development and Settlement Schemes

The policy makers of Sri Lanka have felt the need for regional level strategies to development and this has mainly been due to the electoral representation system that has been in operation since the early 1930s. Prior to the 13th century the Dry Zone Lowlands had flourished as the cradle of the ancient Sinhala civilization. After 1235 AD due to various physical political and other factors there commenced a period of settlement desertion of the Dry Zone and gradual drift of population towards the Southwest. Despite the efforts of the state at the turn of the 20th century people could not be induced to migrate to the Dry Zone. Considering this situation, during the first phase of passant settlement development in the Dry Zone in 1939 that state aided colonization became attractive to settlers. The focus of development was on the restoration of ancient irrigation works that could be restored at relatively low costs. The earliest among these efforts were the colonies established in the late 1920s at Nachchaduwa in Anuradhapura District, Beragama in Hambantota District, and Tabbowa in Puttlam District, which involved not more than the rehabilitation of the existing reservoirs and channels.

In the 1930s, soon after the Donoughmore reforms, the government established colonization scheme through restoration of ancient irrigation works. The irrigation system in the Minneriya, which had fascinated, the British writers of the 19th century, was the first scheme to be implemented in the Dry Zone. Largely as a result of the efforts of late D. S. Senanayake and despite the setbacks, which had arisen out of the bleak economic conditions of the depression, Minneriya scheme was restored and the colonists began to settle by early 1936. Several other large schemes such as Iranamadu, Minipe, Prackrama Samudra and Elahera, which had the advantage of low-cost restoration, followed closely on the heels of the Minneriya scheme.

With the spectacular success achieved by the anti-Malaria drive launched in 1942, within a short span of four years, Malaria, one of the most formidable obstacles to resettlement of the Dry Zone, was eliminated. Thus by 1948, eleven major colonization schemes with an aggregate of about 16.000 peasant families has been established in the Dry Zone. The colonization program contained a number of components vis-à-vis land settlement, provision of irrigation, agricultural development, food production, and infrastructure development, all targeting area development at on gigantic scale, A prime objective of the colonization program was to make a self-sustaining population by a self-reliant “rural gentry”. All these development approaches can be identified as area development programs.

The spatial pattern of colonization, which was developed during the 30 years following independence because of restorations of ancient irrigation works, has shown certain regional diversities within the Dry Zone (Table 5). They could be explained with reference to spatial variation in both environmental conditions as well as the nature of the legacies from the past that was available for resuscitation.

As an area development program, Gal Oya Multi-Purpose River Valley Project was one of the large-scale interventions of area development in Sri Lanka. A technical survey which was conducted in 1936 indicated that Gal Oya, if systematically regulated, could not only lower the frequency and intensity of its flooding, but also irrigate a vast extent of land in its middle and lower reaches. This survey was followed by further investigations by 1946, culminating in the formulation of a Plan for the entire Gal Oya catchment area and commenced in 1949. This development program was a replication of “Tennessee Valley Development Program” in United States of America.

Irrigation and land alienation in the low country Dry Zone brought about a considerable expansion of area under agriculture. Between 1952 and 1962, there was a 212% increase of agricultural lands in the north Central Province from

![]()

Table 5. Peasant colonization scheme based on restored irrigation works up to the end of 1978.

1. Central Region: Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, and Matale District, Western part of the Trincomalee District, the North Eastern periphery of Kandy District. (The region includes, almost entirely the areas that were served by the gigantic hydraulic works of the Rajarata period. 2. Northern Region-Jaffna, Mullaitive, Vavuniya and Mannar (physical conditions for irrigation are distinctly inferior to those of the Central Region). 3. Eastern and South-Eastern Region-Batticaloa, Ampara, Monaragala, Badulla, Hambantota. 4. North-Western Region-Puttlam and Kurunegala. Source: Development and Change in Sri Lanka.

29,770 ha. to 110,990 ha. In addition to the extension of area under paddy and other crop yields have increased in the areas served by the major colonization schemes due to the extensive use of high yielding seed varieties, fertilizers, pesticides, and weedicides. In the Eastern and North Central Provinces, the average annual paddy production increased by 1696% and 917% respectively between 1944/45 and 1946/47 to 1987/88 and 1989/90.

One of the main objectives of Colonization schemes was to promote the migration from rural to rural. As a result of that, city-ward migration was reduced and retains the people in the Dry Zone. Colonization scheme led to the emergence of a new migration stream, which transferred 128,000 persons to the low country Dry Zone between 1946 and 1953. Thus two main destinations of migrants could be observed in the country after 1946 viz., a rural to urban migration to the core especially Colombo District and a rural to rural migration to the Dry Zone especially North Central and North Western Provinces in the periphery of the country. During the inter census decade of 1953-1963 and between the inter census period of 1963-1971 internal migration followed the same pattern. At the census of 1981 too, two areas that had major net gains of over 200,000 migrants were Colombo and Gampaha Districts in the core of the country (203,000) and the North Central Province (228,720) (Wanasinghe 2002).

3.6. Mahaweli Development Project

In the early 1970s, another massive River Basin Development program, The multi-purpose Mahaweli Development Project, was launched covering approximately 40 percent of noncontiguous land area under a number of irrigation systems mainly in the districts of Central, North-Central, and Eastern Provinces of the periphery of Sri Lanka (Wanasinghe, 2002).

The Mahaweli multi-purpose Development project aimed to supplying irrigated water to new lands of 260,000 ha and augment the water supply of existing 400,000 ha croplands, increase agricultural production, provide land to farmer and non-farmer families, generate hydro power and create new employment opportunities. Apart from generating 56% of the power requirements for the whole country, it has settled 193,120 farmer and non-farmer families by 1995; provided physical and social infrastructure for settlers; increased the area devoted to paddy and other field crops and attempted to diversify the economy through livestock farming and enterprise development. The extent of land under paddy in the region increased by approximately 128,250 ha, which amounts to 16% of the total paddy lands in the country.

The Mahaweli lands yielded 20.9% of paddy production and had a marketable surplus of 85.3% of the total. The area under the field crops as well as their share in the total household income had increased thus reducing the excessive dependency on paddy (Wanasinghe 2002). In order to facilitate the provision of services and facilities to the settler population and to provide off-farm employment opportunities, three-tier hierarchies of service centers or central places such as hamlets, village, centers and townships have been introduced to irrigation systems. About 8 townships and 20 village centers have been established to serve 31,000 settler families in project area. On the other hand, the number of service centers for people in the other parts of the North Central Province is grossly inadequate and essential rural-urban linkages are either weak or absent.

Within the Mahaweli Project itself certain problems have arisen in recent years that tend to prevent the Mahaweli Project area from playing a more significant role in regional development. Although there was an equitable distribution of land at the inception and the average income of farmers has increased in the different irrigation systems there has been a wide variation in income levels as highlighted by Siriwardana and Wanigarathne. Further about 85% of the paddy and about 90% of other food crops in the Mahaweli is sold outside of the project area. Wanigarathne noted that distress sales amount to over 60% of the market surplus. According to Wanigarathne, employment opportunities in the non-farm sector for the second and third generation of farmer families would become a major issue in the near future.

Alienation of land in the periphery for agriculture and settlement has been another type of state intervention that aided in ameliorating excessive polarization. In the more densely populated Wet Zone where there was a considerable number of landless families during the early decades of the 20th century land was provided from within the region itself under Village Extension Schemes and Highland Colonization Schemes. By 1948, and 65,000 ha of Crown land or land purchased from the private sector had been subdivided under Village Extension Schemes, among 125,000 rural families. By 1973, the total land area redistributed under Village Extension Schemes amounted to 315,000 ha. Although these two schemes benefited poorer landless families in the Wet Zone, however majority of these families did not have enough access to basic education, health and other facilities.

3.7. The Integrated Rural Development Program (IRDP)

The Integrated Rural Development Program (IRDP) commenced in 1976 with the planning of the Matara and Kurunegala IRDPs and the subsequent launching of those respective projects in 1979 with donor assistance to develop areas not covered by the three lead projects undertaken by the state viz., the rural based Mahaweli Project in the periphery, the urban based Urban development and Housing Program and the Free Tread Zones (export Promotion Zones) located in the Western Province or core which focused on industries (Wanasinghe, 2002). The objectives of the IRDP can be summarized as flows.

1) Enhance the general quality of living standards and expand the economic opportunities.

2) Focus development efforts specially to meet local needs and to encourage local initiatives.

3) Trim down inter-district and intra district disparities and hence prop up more balanced growth.

4) Encourage quick responsive, mutually supportive, low cost productive investments along with necessary institutional improvements.

5) Assist in the removal of bottlenecks and constrains, thereby contributing to the better utilization of the districts’ resources.

6) Improving the planning process in the District (Wanasinghe, 2002; Ramakrishnan, 1987).

By 1999 the cumulative expenditure for IRDPs and projects in former IRDP areas such as the Matale Regional Economic Advancement Project (REAP), North Central Participatory Rural Development Project (PRDP) and Batticaloa Development and Rehabilitation Project (BDRP) was as high as Rupees 11, 680, million. The foreign aid commitment is approximately 83% of the total. The major achievements have been in social mobilization and in the delivery of social and economic infrastructure to the district concerned (Lindahl et al., 1991; Moore, 1995; Amarasinghe, 1996) but as explained by Wanasinghe (2002) IRDPs have not made a positive impact on the overall development of each district. The main thrust of the IRDPs in other developing countries too was on agricultural change while little consideration was given either to industrial growth or to the vital role service centers can play in the rural economy as pointed out by Baker and Pedersen (1992). Asian Development Bank points out that the food and nutrition are serious health problems in the civil war conflict areas of Sri Lanka. On the other hand, there is high rate of unemployment rate. Economically inactive people of the estate sector and rural sector of Sri Lanka are 25.5% and 33.5% at the first quarter of 2021.

The IRDPs in Africa according to Baker and Pedersen, attempted to change the rural urban balance by bypassing the small towns, which led to an even greater centralization of decision-making. A similar situation has arisen in Sri Lanka too (Wanasinghe, 2002). Thus, IRDP represented the first explicit countrywide program of regional development in Sri Lanka and its development and implementation was entrusted, professionally. Until IRDP functioned as the main vehicle for addressing regional development concern with project has been implemented in 18 of the 25 District in Sri Lanka.

3.8. The Regional Economic Advancement Program (REAP)

The need to shift away from welfare and infrastructure-based development strategy of the IRDP and to focus on economic growth and income generation in the different districts has been felt for some time. Hence in 1997, a new concept, Regional Economic Advancement Program (REAP) was initiated with the objectives of generating economic growth and creating employment opportunities in rural areas.

Sri Lanka unveiled a new approach to regional development. Sought to capitalize on the achievements of IRDP and to mitigate the latter’s shortcoming. IRDP has reflected a general rural development approach to regional concerns with major emphasis on rural infrastructure creation and mobilization of the rural people as well as a somewhat palliative approach to poverty alleviation. While paying due attention to the board concerns of IRDP, aims for each regional project to concentrate on a limited and manageable number of activities that promote regional growth through the expansion of regional production and the generation of increased regional income and employment opportunities. As a successor to IRDP, REAP, aims to assist farmer to move from fully or partly subsistence agriculture farming, through improved production process Markets and other facilities. REAP also aims to help local people and outsiders to identify and develop local no-frame enterprise. REAP will also help to develop detailed local economic development plans because of which regions and associated sub-regions can advance to new levels of prosperity.

The redirection of the approach is from an essentially rural to integrated rural/urban development; poor rural area focus to entrepreneur focus; primary subsistence to market oriented production and value addition and government dominated programs to private sector led programs (Karunanayake & Narman, 2002). To achieve these objectives, REAP concentrates on market-based farm enterprise development and specialization; rural non-farm enterprise development; integrated village development and the regional development plans. Unlike the IRDPs, REAP expects to focus more on balanced regional development but in the absence of comprehensive regional plans for districts or provinces, the question arises whether REAP can make a worthwhile contribution to regional development. Another major issue highlighted by Karunanayake and Abhayarathna (2002) is the way the REAP strategy relates to the poorest segments of rural society who have hitherto been supported by social welfare-oriented programs of the IRDP’.

3.9. Special Area Development

There are some issues that, especially owing to the nature of their externalities, which cannot be readily solved through the planning regions that are defined through the administrative system (Province, District, Division, etc.). An example may be the case of a port that is located in one Province, but serves areas beyond the Province where it is located. Another example may be that of externalities arising from shared resources such as watersheds. In the mid-1990s, RDD began to identify special area development programs which provide a regional framework within which to address such concerns, and to coordinate respective provincial and sub-provincial initiatives. So far, the Southern Development Area under the Southern Development Authority (SDA) has been identified. It is a functional area based on the Problems of economics malaise that have plagued the Southern Area of Sri Lanka for some decades. Today, there are several special regions and the government, Uda Rata, Central Province, Eastern, North and eastern among them have identified ministries. After the Tsunami devastation, the Tsunami affected areas have been identified as an especial development region by the government and international community too. Regionalization continues mostly in an ad hoc manner. Many different such programs may be introduced at varying spatial levels.

3.10. Poverty Alleviation Programs

The government has been supporting the poorer segments of the population through income transfers in cash or kind. Janasaviya is a giant pro-poor program; it had been in operation since 1989. Janasaviya assisted approximately 420,000 families who lived below the poverty line of Rs. 700 monthly family income. Approximately each family receives Rs. 2000 income transfer of which 1458 for consumption and savings. The objective was to promote self-reliant development of the poor and to upgrade their quality of life.

The most recent pro poor national program Samurdhi has benefited nearly 1,973,200 families in 1998, which is approximately 51% of the total families. This proportion is estimated to be considerably higher than the percentage of deserving low income families which amounted to only 30% - 40%. In addition to income transfers, opportunities are being provided by Samurdhi to promote savings and to obtain credit for the establishment of enterprises or other income generating activities as well as to assist the recipients to meet their social obligations. Nearly 50 percent of the families of the country are below the poverty line today even after 50 years of independence.

3.11. Regional Industrialization

Decentralization of industries in Sri Lanka exhibits a market concentration in the Western Province (Core region of the country). This region has attracted the majority of private sector entrepreneurs with the exception of raw material-oriented industries such as processing of tea and other agro based products and the manufacturing of porcelain and chinaware, pottery, bricks, wood craft and market oriented industries such as the preparation of food items for a localized market. Other enterprises located in the periphery include traditional handicrafts based on skilled labor and service the preparation of food items for a localized market. Other enterprises located in the periphery include handicraft based on skilled labor and service industries. In the central province for example the majority of the industries are medium, small and micro-enterprises or 52% of which are agro-based industries while others are either mineral-based, wood based or metal-based industries.

In the area of low land Dry Zone, small and micro-level rice mills and food processing industries are very common, especially in the districts of Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa and Hambantota. However, majority of the large-scale industries, which are managed by both government and private sector, are concentrated in the core or Western Province of the country. Under the patronage of foreign and local investment launched two Investment Promotion Zones (IPZ) at Katunayaka in 1978 and Biyagama in 1982 both zones have been located in the core, especially in Gampaha District. In 1992, third IPZ was located at Koggala in Galle district of Southern Province. In 1999, three mini Investment Promotion Zones called Export Processing Zones have been established at Malwatta, Meerigama, Wathupitiwala in Gampaha District.

In decade of 1990, the garment industry in the country had long-drawn-out rapidly, providing employment to over 150,000, as it was a highly labor exhaustive industry but was mainly concentrated in the core area. To reduce this regional imbalance, government decided to deconcentrate the industries to periphery too. Thus in 1992, the government launched the 200 Garment Factories Program. 200 Pradeshiya Sabha areas were identified as appropriate for locating the new garment factories. It was expected that each factory would employ at least 500 persons who were to be recruited from Janasaviya recipients in the Pradeshiya Sabha areas in which factory was to be located. By 1998 the Central Bank reported that only 160 factories opened under the 200 Garment Factories Program was functioning. Of this number 128 were located outside of the core area, which provided employment to approximately 67,000 persons. However, after the quota period in 2005, garment sector of Sri Lanka faces many problems.

Under the promotion Act No. 46 of 1990 and the new Industrial Strategy for Sri Lanka announced in 1995 special emphasis was placed on regional industrial development. Yet in spite of the incentives and benefits offered, entrepreneurs are more attracted to Industrial Estates, Industrial Parks, and mini–Export Processing zones that have been opened in the core area such as Seethawaka Mathugama, Homagama Minuwangoda, Kalutara, Wathupitiwala, Meerigama and Malwatta.

There are systematic attempts at regional development in Sri Lanka that appear to be grounded in the growth pole growth center concept. This is the main paradigm that underpins the work in urban/municipal development, Industrial parks etc. There is some validity to the observation that the Wet Zone of Sri Lanka with its higher concentration of towns (growth poles/centers) is more developed than the Dry Zone. The strengthening of growth centers in the Dry Zone therefore seen as a valid national developing strategy.

4. Conclusion

As a continual process of urban biased development since 4th century BC, the first kingdom of Anuradhapura was based on the Anuradhapura city which was the capital of Sri Lanka for 1400 years continuously. Even during the colonial period, the infrastructural development was based in Colombo port and Colombo city. Colombo Megalopolis development is one of the mega projects of contemporary Sri Lanka and the master plan of the Western Region Megalopolis (WRM) has been presented in 2016. The main objective of the project is to upgrade the Colombo City for high income developed country in near future. The WRM aims to implement 150 mega projects in the Western Province and to create 500,000 new jobs. On the other hand, the infrastructural facilities will be expanded for providing services for 8.5 million population in the city.

Consequently, even in the next decade, the regional development disparities will continually be widened. Simultaneously to the urban biased development, the rural sector of Sri Lanka highly depends on the government subsidies, and there are no significant projects to increase the non-agricultural sector economic activities. In the current trends, the young generations of the rural areas plan to migrate to the cities for better livelihood. Both well-educated skilled laborers and the less educated non-skilled laborers are pulled into the cities. The hopeless rural employees are disgusted, and they are in huge unrest. This may cause unexpected conflicts which will be based on different reasons depending on the consequent contexts. Therefore, the government should pay the quick attention with short term to long term strategies to make balanced human wellbeing in both cities and the villages in Sri Lanka.