Survey of Bereavement Care Provided by Home-Visit Nurses for Bereaved Families in Japan ()

1. Introduction

The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan in 2006 [1] estimated that 1.65 million people would die in 2030, and that about 890,000 people would die at medical institutions, 90,000 at nursing care facilities, and 200,000 at their own homes. About 470,000 people (approximately 28%) were categorized as “Others (Nowhere to be cared for)”. As the number of medical institutions and facilities are unlikely to increase in the future, about 670,000 people (approximately 41%), including the 470,000 immediately above, will die at home served by home-visit nursing care. Hence, promoting end-of-life care at home is important.

Home-visit nurses play an important role as professionals in charge of home care, and pre- and post-bereavement care for bereaved families is included in home-visit nursing services [2]. However, bereaved families are not always provided with care after bereavement. A previous study reported that 37.4% of home-visit nurses always provided post-bereavement care; however, 46.2% only provided this on a case-to-case basis [3].

Among studies on grief and bereavement care published outside Japan, Stroebe and Stroebe reported that 42% of people with spousal loss suffer moderate or more serious depression 4 to 7 months after the death of the spouse [4]. Futterman et al. reported the importance of bereavement care, pointing out that other than depression, psychiatric illnesses due to increased antipsychotic drug intake and increased alcohol intake were related to higher death rates [5].

Kreicbergs et al. conducted a questionnaire survey with 449 parents who had lost their children due to malignant diseases more than four years previously, and investigated anxiety, depression, mental satisfaction, and quality of life (QOL) [6]. They reported that a 4- to 6-year post-bereavement group suffered more from anxiety and depression than a 7- to 9-year post-bereavement group.

Lugton reported that the staff of St. Columbus Hospice, United Kingdom, held weekly follow-up meetings with physicians and nurses who were familiar with the bereaved families to identify families who were particularly distressed and those in need of special support as a post-bereavement follow-up service [7]. Another previous study reported that medical institutions and hospices evaluated bereavement risks of families by investigating whether families accepted the illness and terminal condition of their family member(s) so that these families could receive appropriate support when bereavement occurred [8].

There are other countries where guidelines for psychological and bereavement support are available for family caregivers [9].

A questionnaire survey targeting bereaved families with family members who died in hospice or palliative wards in Japan found that about 40% of those affected experienced poor health conditions after bereavement, and about 50% of respondents complained of physical illness/symptoms that were due to the bereavement [10]. As situational factors related to grief decrease one year after bereavement [11], it is necessary to provide continued support, in particular for older people who show more physical reactions than younger people to grief [12].

Currently, Japan has no established system following the death of a family member. Medical service fees for the bereaved family are not covered by the national insurance program in Japan, and eligibility for medical insurance starts only after symptoms, such as depression, appear and are diagnosed. Regular home-visit nursing is prioritized over bereavement care, which is not covered by the medical insurance, and there are ambiguities in the role of home-visit nurses due to lack of knowledge of such care for bereaved families.

With the revision of medical treatment and long-term care fees (insurance mandated) to promote the regional comprehensive care system in 2018, the importance placed on flexible services for people with high medical dependence has increased. Home-visit nursing stations are required to provide medical treatment for those who need 24-hour attention and everyday homecare to enable these patients to live in the community.

Sakaguchi et al. reported that many nurses experience feelings of sadness, fatigue, and helplessness after the death of patients [13]. Nurses who had little experience in end-of-life care tended to feel “helplessness”, “responsibility”, and “anxiety”, suggesting the necessity of providing support for the mental reactions of nurses including educational support. Leick and Davidsen-Nielsen focused on aid workers as an at-risk group who suffer from a complex grief state, their findings suggested the necessity for nurses to look at their own psychologically unprocessed losses [14].

Sakashita reported that in terminal care, nurses needed mental health care skills to engage in terminal care with a positive attitude because they were subjected to stress every day in the process of dealing with patients, and that it was necessary to create an environment that supports the mental conditions of nurses who feel anxiety and helplessness [15].

These stressors necessitate continuous attention to bereavement care so that terminally ill patients, family caregivers, and medical professionals can proactively realize death at home or end-of-life care without undue stress. We conducted semi-structured interviews with managers of home-visit nursing stations in Japan, and established that the structure of the bereavement care performed by the managers was continuous care with a view to building a family life, and that it involved a series of home-visit nursing processes [16].

For this reason, we focused on the need for continuous nursing care towards bereavement care at the home of patients. We found that there were families who suffered from morbid grief, mental disabilities, and the loneliness of living alone after bereavement at their homes or hospices.

In bereavement care for families of cancer patients provided by medical institutions in Japan, clinical nurses play the main role, particularly in medical facilities with palliative care units [17]. As some nurses become confused as to how to respond to the families of the patients while performing daily tasks in the clinical setting, educational support for nurses in charge of bereavement care is necessary [18].

Worldwide, bereavement care research for families has been conducted for various purposes [19]; however, no nationwide studies reported details of bereavement care services by systematically focusing on home-visit nurses. This study aims to investigate the implementation of bereavement care and the relationship between the demographics of home-visit nurses and bereavement care.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

The study population was drawn from home-visit nurses working at 2200 facilities randomly selected from the member list of the Home-visit Nursing Stations of the National Nursing Business Association.

2.2. Survey

A cross-sectional survey was conducted using anonymous self-rating questionnaires, administered between September and December of 2014. The questionnaires for home-visit nurses were sent to the 2200 facilities by post. We explained that returning the questionnaire would be regarded as consent to participation.

2.3. Surveyed Items

The demographic characteristics were as follows: length of home-visit nursing experience (in years), length of hospital nursing experience (in years), job title, employment type, type of affiliated organization, presence of extra fees for 24-hour-a-day care, date of death (year) of patients, and the method of cooperation between hospitals and community-based homecare.

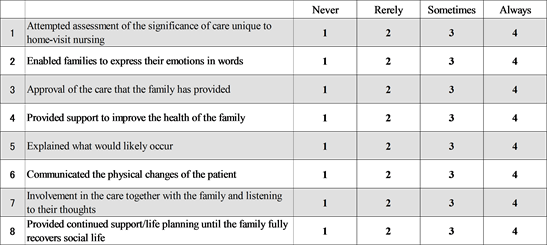

We created 8 question items for care before and 10 items for care after bereavement based on a previous study [20] [21], and the results of discussions with managers of home-visit nursing stations who are experts in terminal care [16] [19]. The validities of these items were examined through a discussion focusing on risk management [22].

Participants were requested to answer by recalling one patient they were in charge of. The responses to questions about care frequency were on a 4-point scale: “Always” (4), “Sometimes” (3), “Rarely” (2), and “Never” (1).

2.4. Analysis

Demographics of home-visit nurses and facilities were analyzed by descriptive statistics. If a participant answered “Always” to the questions regarding the provision of pre- and post-bereavement care, the answer was regarded as “Provided”. The rate of providing care was calculated by the ratio of the answers that were regarded as “Provided”.

Furthermore, we performed a multiple logistic regression analysis to identify the relationship between the rates of provision of bereavement care and the demographics of the home-visit nurses. In the analysis we used the presence or absence of each of the pre- and post-bereavement care items as the dependent variables, and sex, home-visit nursing experience, job title, employment type, and whether the facility provided 24-hour services as independent variables. For the provisions of care for bereaved families and the budget available, the ratio was calculated by simple aggregation. For the statistical processing, SPSS ver. 21.0 was used, and the significance level was set to 5%.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of Nayoro City University and in conformity to the research guidelines of the university that the first author belongs to (approval number 13-012).

The authors explained the data management methods, anonymity, and privacy protections of the participants throughout the entire process of the study in writing. It was also explained that there would be no advantages or disadvantages whether participating or not participating, or discontinuing participation; that the study results would be provided in the form of feedback; and that the returning of the questionnaire would be regarded as consent to participation.

3. Results

Of the 2200 questionnaires distributed, 688 responses were collected (collection rate 31.3%), and 649 that had no missing values in demographic questions were analyzed.

3.1. Demographics of Participants

Details of demographics were as follows: females, 97.4%; mean age, 48.7 years (SD ± 8.0); administrative staff (management staff or chief), 80.4%; and staff nurse, 19.6%.

The mean length of home-visit nursing experience was 10.4 years (SD ± 6.4) and that of hospital nursing experience was 15.2 years (SD ± 9.2). Those who had 15 years or longer home-visit nursing experience accounted for 29.0%.

The mean length after the death of patients (years) recalled at the time of the bereavement care survey was 1.2 years (SD ± 1.4), and 94.8% of the facilities provided 24-hour services (Table 1).

3.2. Bereavement Care for Patient Family: Provision Rates of Pre- and Post-Bereavement Care Units

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the rates of provision of pre- and post-bereavement care for bereaved families.

The highest scores were “Approval of the care that the family has provided” (90.1%), “Involvement in the care together with the family and listening to their thoughts” (84.0%), and “communicated the physical changes in the patient” (82.6%). “Provided continued support/life planning until the family fully recovers social life” had the lowest score (10.9%) (Figure 1).

![]()

Table 1. Demographics of participants.

![]()

Figure 1. Provision rates of pre-bereavement care (%).

![]()

Figure 2. Provision rates of post-bereavement care (%).

For provision of post-bereavement care, the three highest scoring items exceeded 70%: “Tried to convince the family that the care they had provided was good” (80.7%), “Approval of the care that the family has provided” (77.2%), and “Involvement in the care together with the family and listening to their thoughts” (70.9%). However, two items were below 10%: “Provided continued support until the family fully recovers social life” (7.7%), and “Involved in building a life after bereavement” (2.6%) (Figure 2).

3.3. Relationship between the Demographics of Home-Visit Nurses and the Rates of Provision of Bereavement Care by Multiple Logistic Regression Analysis

Table 2 and Table 3 show items that significantly correlated based on the multiple logistic regression analysis. In the analysis, the dependent variables were presence or absence of each of the pre- and post-bereavement care items, and the demographic variables shown in the tables were used as independent variables.

In pre-bereavement care, odds ratios of the following items were significantly different: “Involvement in the care together with the family and listening to their thoughts” was higher in female nurses than in male nurses (3.45 times); “Enabled families to express their emotions in words” was higher in respondents with 15 years or longer home-visit nursing experience than in those with less than 5 years (1.94); and “Provided support to improve the health of the family” was higher in respondents with 10 to 15 years of experience and in those with 15 years or longer experience than those with less than 5 years of experience (1.63 and 1.88, respectively).

![]()

Table 2. Demographic factors related to the rate of provision of pre-bereavement care by multiple logistic regression analysis.

*p < 0.05 **p < 0.01.

![]()

Table 3. Demographic factors related to the rate of provision of post-bereavement care by multiple logistic regression analysis.

*p < 0.05 **p < 0.01.

The response to “Enabled families to express their emotions in words” with facility managers was 1.56 times higher than that of staff. Compared to the participants working in a home-visit nursing station without 24-hour services, those in nursing stations with 24-hour services had higher odds ratios than those without 24-hour services in the following items: “Attempted assessment of the significance of care unique to home-visit nursing” (3.07 times), “Explained what would likely occur” (3.52 times), and “Involvement in the care together with the family and listening to their thoughts” (2.85 times).

In post-bereavement care, participants with 15 years or longer home-visit nursing experience had statistically significantly higher odds ratios in the following items in Table 3 compared to those with less than 5 years of experience: “Attempted assessment of the significance of care unique to home-visit nursing” (1.97 times), “Enabled families to express their emotions in words” (1.93 times), “Explained the physical changes in the patient after death and their reasons” (1.89 times), and “Learned about the regrets of the family, accepted their thoughts, and showed acceptance” (1.76 times). There were no statistically significant differences with other items of demographics.

4. Discussion

4.1. Bereavement Care Provided for Bereaved Families by Home-Visit Nursing Services

The three highest scoring questions advocating provision of pre-bereavement were “Approval of the care that the family has provided”, “Involvement in the care together with the family and listening to their [thoughts] ideas”, and “Communicated the physical changes in the patient”. “Provided continued support/ life planning until the family fully recovers social life” was the lowest at about 10%. The results show that the degrees of provision of care items that needed to be continuously provided after discharge were low. Most home-visit nurses provided psychological support for the family such as assessing the family's efforts and listening to their ideas.

Grande and Ewing reported that the degree of providing mental support (especially psychological support) was more important to the bereavement experienced by caregivers than the help provided to patients prior to death at their preferred place [23]. It is necessary to establish a system that makes it possible to provide detailed multifaceted information, such as about the cost for home-based terminal care, by promoting cooperation among different occupations and care support specialists to decrease the necessity of long-term nursing care for bereaved families [24]. It may be necessary for home-visit nurses to perform risk assessment of the presence of pathological grief before bereavement and provide intervention depending on individual needs.

For the provision of post-bereavement care, “Tried to convince the family that the care they had provided was good”, “Approval of the care that the family has provided”, and “Involvement in the care together with the family and listening to their thoughts” were the three most frequently suggested items; however, “Provided continued support until the family fully recovers social life” and “Involvement in reestablishing daily life after bereavement” scored less than 10%. In post-bereavement care, most home-visit nurses provided psychological support for the family as pre-bereavement care, but continued support for families to return to social life was less frequently provided.

These findings suggest that home-visit nurses do not provide family caregivers with continued support as a “support activity for the family”. A bereavement care survey of 296 home-visit nursing stations nationwide reported that about 80% of valid responses indicated that they provided bereavement care, and 90% visited homes [25]. This study also reported that the support was mainly for mental aspects; “instrumental support”, which directly dealt with daily life problems and “informational support”, which provided knowledge about the process of grief, accounted for less than 50%. In the present study, the support for the mental aspects accounted for more than 70%.

Currently, regular home-visit nursing is prioritized over bereavement care, which is not covered by medical insurance, and there are ambiguities in the role of home-visit nurses due to lack of knowledge of such care for bereaved families. However, even in this situation, home-visit nursing stations visit bereaved families to provide bereavement care. This suggests that home-visit nurses themselves [organize the thoughts and ideas of their own and the families] through interaction with the bereaved families [26] [27]. It is necessary to establish concrete measures to assist home-visit nurses to be able to provide these needs.

4.2. Relationship between the Demographics of Home-Visit Nurses and the Rate of Provision of Bereavement Care

In the comparison of the rates of provision of pre-bereavement care of females and males, the odds ratios of “Involvement in the care together with the family and listening to their ideas” in the female nurses was 3.45, significantly higher than that of the male nurses. This suggests that female nurses were more likely to respond attentively to the perceived feelings of the bereaved families.

In pre-bereavement care, the longer the experience of home-visit nursing, the higher the rate of provision of “Enabled families to express their emotions in words” and “Provided support to improve the health of the family”. In the multivariate analysis that used adjusted demographic factors other than home-visit nursing experience, the odds ratio of care provision in nurses with 10 years or longer experience was significantly higher than for those with less than 5 years.

In post-bereavement care, the longer the home-visit nursing experience, the higher the rate of provision of bereavement care in seven of the 10 items. In the results of the multivariate analysis, the odds ratios of the following items in nurses with 10 years or longer experience were statistically significantly higher than those with less than 5 years of experience: “Attempted assessment of the significance of care unique to home-visit nursing”, “Enabled families to express their emotions in words”, “Explained the physical changes in the patient after death and the reasons for the changes”, and “Learned about the regrets of the family, accepted their thoughts, and showed acceptance”.

In the present study, most participants were facility managers (80%). It can be inferred that facility managers improve their expertise through the complex situations experienced, including through facility management and staff education, and that such experience contributes to the higher scores in the degrees of provision of post-bereavement care than study participants with shorter periods of experience.

Home-visit nurses, who play a part in homecare support, need to have and benefit from a high level of expertise, medical care skills, and communication skills with different professionals. Komatsu, Takiuchi, and Maeda reported that nurses with longer hospital or home-visit nursing experience acquired wider knowledge and skills in four categories covering both the pre- and post-bereavement periods [28].

Home-visit nurses acquire knowledge and skills for care in the period neardeath or bereavement through the experience of providing terminal care. This suggests the necessity of providing support for less experienced nurses in this area.

Unlike the nursing provided by many nurses in wards, the work of home-visit nurses requires them to visit families independently or with a few other nurses, and also to deal with the process of the death of patients. In addition, Shibata, Tomita and Takayama reported that “difficulty due to independent visits” and “anxiety and difficulty due to lack of knowledge and skills of home-visit nursing” were difficulties encountered by nurses [29].

This suggests the necessity of training home-visit nurses. However, the standard regulations for staff allocation in home-visit nursing stations is 2.5 nurses or more, much lower numbers than those required of hospitals. This is due to the difficulties of home-visit nursing stations to assign full-time staff to educate new nurses, and with the managers that are acting in the role of trainer for the home-visit nurses.

It is essential to offer 24-hour services to deal with end-of-life patients.21 The results of the present study show that the odds ratios of items of providing care following bereavement were significantly higher in the home-visit nurses affiliated with facilities with 24-hour services than those without such services.

With the revision of medical treatment and long-term care fees in Japan in 2018, additional fees for 24-hour services were acknowledged and included [30]. However, there are still regions where social resources are insufficient.

5. Limitations and Strengths of the Study

This study has a number of limitations. The valid response rate was low at about 30%, and this presents a limitation to any generalization of the results. As more than 6 years have passed since the survey was conducted, the current situation might have markedly changed. The bereavement care system in Japan remains the same. However, the current situation should be investigated in the future because the bereavement care by home-visit nurses may have changed. In addition, because the findings are based on self-assessment by participants looking back on the care activities they provided, information bias must also be acknowledged. However, as the participants were randomly recruited from home-visit nursing facilities nationwide, the findings provide important data and information about the present conditions and issues of bereavement care provided by home-visit nurses in Japan [31].

This study was conducted with the background that there is no agreed upon standard for bereavement care in Japan. Assisting a family with terminal care conducted at home is considered to be an occasion where the skills of home-visit nurses become an issue. Presently, it is at the discretion of the nurse in charge.

Further studies are needed to clarify details of the problems home-visit nurses are aware of in supporting bereaved families in the general community.

6. Conclusions

The three most frequently provided aspects of pre-bereavement care were “Tried to convince the family that the care they had provided was good”, “Approval of the care that the family has provided”, and “Involvement in the care together with the family and listening to their thoughts”. The lowest score was “Provided continued support/life planning until the family fully recovers social life” at about 10%.

The three most frequently provided aspects of post-bereavement care were: “Tried to convince the family that the care they had provided was good”, “Approval of the care that the family has provided”, and “Involvement in the care together with the family and listening to their ideas”. The two items with the lowest scores were “Provided continued support until the family fully recovers social life” and “Involvement in reestablishing daily life after bereavement” (less than 10%).

The odds ratio of the “Involvement in the care together with the family and listening to their thoughts” of the female nurses was statistically significantly higher than the male nurses. The odds ratios of the “Enabled families to express their emotions in words” and “Provided support to improve the health of the family” were significantly higher in the home-visit nurses with 10 years or longer home-visit nursing experience than in the home visit nurses with less than 5 years of experience. In the comparison between facilities with and without 24-hour services, the degrees of care provision of three items were significantly higher in facilities with 24-hour services: “Attempted assessment of the significance of care unique to home-visit nursing”, “Explained what would likely occur”, and “Involvement in the care together with the family and listening to their thoughts”.

For post-bereavement care, the degrees of provision of more than half of the items were significantly higher in the home-visit nurses with longer home-visit nursing experience, and in facilities with 24-hour services. It is necessary to establish a framework that makes it possible to provide family caregivers with continued support, such as follow-up services that also include physical aspects; training; and a cooperation arrangement, to obtain people who can help or substitute long-term care in the community. Providing 24-hour services is essential to help people with home medical care and family caregivers who take care of family members alone, and at the same time it is necessary to strengthen education to develop the skills of home-visit nurses.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our gratitude to the participating managers for their cooperation.

This paper is a revised version of that presented at the 78th Annual Meeting of Japanese Society of Public Health.

Questionnaires

Please answer by recalling one client you were in charge of

I. How much terminal care do you think you provided before the passing away of the patients?

Pre-bereavement care

II. How much terminal care do you think you provided after the passing away of the patients?

Post-bereavement care

III. Length after the death of patients recalled at the time of the survey

( ) years

IV. Important cooperative measures between hospitals and community-based homecare

(Multiple answers)

1. Discharge summary 2. Pre-discharge joint conference 3. Care service staff meeting 4. Other ( )

V. Demographics of participants