Bank Lending Channel of Monetary Policy: Dynamic Panel Data Evidence from Sierra Leone ()

1. Introduction

Since the pioneering work by Bernanke and Blinder (1988) and later explored by other authors (see Bernanke (1993a, 1993b), Bernanke and Gertler (1995), Hubbard (1995) and Kashyap & Stein (1995) among others), there has been a great deal of empirical work in both developed and developing countries trying to investigate the credit view of monetary policy transmission mechanism. In the literature, two sub-channels have been identified through which the credit view of monetary policy transmission operates: First, the balance sheet channel which impacts the net worth of borrowers and therefore their capacity to contract loans and Second, the bank lending channel which operates through the response of loan supply to the economy to changes in the monetary policy stance. Earlier empirical attempts at addressing the question of the validity of the credit channel of monetary policy transmission have largely relied on the use of statistical techniques such as VARs, SVAR, VECMs, and single-equation estimation (see Sims (1992), Christiano et al. (1996), and Kim and Roubini (2000)). This strand of research using aggregate data within a vector auto regression framework was found to be inconclusive due to the identification problem, which makes it difficult to evaluate the impact of monetary policy stance (Bernanke & Gertler, 1995; Kashyap & Stein, 1995; Oliner & Rudebusch, 1995). These authors suggest that a fall in aggregate lending after a tight monetary policy stance may be driven by decrease in the demand rather than supply of credit. According to Bernanke and Blinder (1992), other transmission channels including changes in interest rates or the exchange rate may cause an economic downturn and bank lending follows passively.

Motivated by this identifications problem inherent in using aggregate data and coupled with significant reforms and liberalization of the financial sector in both developed and developing economies, the debate on the role of banks in the transmission of monetary policy has seen renewed interest in the literature. This has engendered a new generation of research on the transmission mechanism of monetary policy using micro level data (disaggregated data set). In particular, studies within this class, investigate whether banks’ loan supply during monetary policy shocks depends on different banks characteristics, namely size, liquidity, capitalization and ownership structure. There are many studies in the literature that have tried to identify the relevance of the bank lending channel of monetary policy transmission using disaggregated bank-level data (see Kashyap and Stein (1995), Kashyap and Stein (2000), Worms (2001), Hosono (2006), Ehrmann et al. (2003), Gambacorta (2005), Chibundu (2009), Zulkefly et al. (2011), Sichei and Njenga (2010), Opolot (2013) and Farajnezhad and Ramakrishnan (2019) among others). The general conclusion in most of these studies is that a tight monetary policy leads to a decline in bank loan supply, which in turn has a negative impact on the economy.

In 2006, a joint IMF/World Bank team undertook a comprehensive review of the financial sector in Sierra Leone under the Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP). The review identified a number of weaknesses in the financial system such as institutional, administrative, legal, and physical impediments. To address these weaknesses, the Sierra Leone authorities developed and implemented a comprehensive strategy-the Financial Sector Development Plan (FSDP)—for the reform of the financial sector, drawing on the recommendations from the FSAP. Resultantly, these reforms led to considerable institutional reforms, including the promulgation of new laws and regulations governing the financial sector and the restructuring and privatization of banks. In addition, the financial sector reforms engendered significant growth in the financial sector, with total assets of the financial system increasing to Le 10.7 trillion as at 31 December 2018 compared to LeLe 5.9 trillion as at 31 December 2014, representing a growth of about 80 percent over the period 2014-2018 (Bank of Sierra Leone Financial Stability Report 2018).

Notwithstanding the significant growth in the financial system since the financial sector reform, the financial system remains shallow, when measured in terms of assets as a percentage of gross domestic product and the limited menu of instruments available in the financial markets. Commercial banks continue to dominate the financial system in Sierra Leone, with total assets amounting to Le8.5 trillion, about 80 percent of the total assets of the financial system. This is followed by the state run National Social Security and Insurance Trust (NASSIT) about 17 percent, Other Financial Institutions (credit-only MFIs (COMFIs), discount houses, financial services association (FSAs) and Apex bank) about 3 percent and community banks less than 1 percent. This characterization of the financial sector points to a possibility of banks dominating the sources of funding for the private sector, strengthening the case for the bank lending channel. In addition, the banking industry in Sierra Leone remains relatively concentrated, with big banks dominating asset and deposits in the industry (Financial Stability Report 2018). This situation has implications for competition in the Industry as banks with a high asset share may be less sensitive to monetary policy shocks as opposed to small banks that highly depend on borrowing from the central bank.

Given that the financial sector in Sierra Leone is dominated by banks, the role of banks in the propagation of monetary policy shocks merits a deeper research. Therefore, this paper seeks to address three fundamental questions: 1) is there a bank lending channel of monetary policy transmission in Sierra Leone? 2) which bank characteristics affect the efficacy of monetary policy shocks in Sierra Leone? and 3) how strong is the monetary transmission via the bank lending channel in Sierra Leone. Understanding how the Bank of Sierra Leone’s policy actions are transmitted to the rest of the economy through the bank lending channel is crucial for appropriate design and efficient conduct of monetary policy. Therefore, the objectives of this paper are to investigate the relevance of the bank lending channel of monetary policy transmission in Sierra Leone and the extent to which bank-level characteristics-size, liquidity and capital-affect the effectiveness of the monetary policy.

A number of studies have examined the importance of different channels of monetary policy transmission in Sierra Leone (Tucker, 2005; Kadima et al., 2008; Ogunkula & Tarawalie, 2008; Lavally & Nyambe, 2019). However, these papers utilized aggregated data within the vector auto regression framework. To the authors’ knowledge, so far there is no empirical study in Sierra Leone that has investigated the transmission mechanism of the monetary policy using bank level data, despite the dominance of banks in the financial sector. Against this backdrop, this study fills the gap in the empirical literature by empirically investigating whether or not changes in the monetary policy stance in Sierra Leone influence bank lending behaviour, i.e. existence of a bank lending channel. It also examines the extent to which bank-level characteristics-size, liquidity and capital-affect the effectiveness of the monetary policy. This is done by utilizing a dynamic panel data method namely generalized method of moments (GMM) procedure, employing quarterly bank-level data of 11 licensed commercial banks in Sierra Leone spanning the period 2014-2018.

Our results indicate that the monetary policy rate significantly and negatively influence banks’ loan supply. This lends support for the existence of the bank lending channel of monetary policy transmission in Sierra Leone and that banks do play a role in Sierra Leone’s monetary transmission mechanism. This result is consistent with the previous findings in a developing country context. Furthermore, commercial banks’ loan supply in Sierra Leone is also explained by past loan supply, economic activity (Real GDP), inflation and the interaction term between bank size and monetary policy rate. However, we find that liquidity and bank capital do not influence banks’ loan supply.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Following this introduction is a presentation of some stylized facts on the structure of the financial sector and monetary policy framework that could aid us with better understanding of the monetary policy transmission in Sierra Leone. Section 3 reviews the existing theoretical and empirical literature. Section 4 describes the data and methodology used in this paper. Section 5 presents the empirical results. Finally, the conclusions and policy implications are presented in Section 6

2. The Structure of the Financial Sector and Monetary Policy Framework in Sierra Leone

2.1. Structure of the Financial Sector and Bank Lending

Architecture of the Financial System

The current financial sector landscape in Sierra Leone is an offshoot of the broad set of reforms initiated by the Sierra Leone government in the early 1990s within the context of the structural adjustment programs. This was complemented by the financial sector reforms which was intended to create a financial system that was competitive, efficient and practice sound corporate governance. These reforms together led to the liberalization of the financial sector and saw the emergence of more financial institutions into the sector. There is broad consensus in the literature that the structure of the banking system and the depth of the domestic financial markets have a significant bearing on the speed and effectiveness of monetary policy transmission. Based on this premise, this paper would attempt to scan the financial sector landscape in Sierra Leone.

Sierra Leone’s financial sector as at 2018 comprised the Bank of Sierra Leone as the apex body, 14 commercial banks, 17 community banks, 11 insurance companies and 68 exchange bureaus, 25 Credit-only microfinance institutions (COMFIs), 4 deposit-taking microfinance (DTMFIs), 1 Apex Bank, 59 financial service associations (FSAs), 2 mobile financial services providers and a nascent stock exchange. There are also 28 National Cooperative Credit Union Association (NCCUA), with 610 groups operating in the financial system.

Asset composition of the Financial Sector

Total assets of the financial system as at end December 2018 stood at 10.70 trillion compared to Le5.90 trillion as at end December 2014. This represents a growth of about 80 percent over the study period 2014-2018 (Financial Stability Report 2018). Commercial banks continue to dominate the financial system in Sierra Leone, accounting for 80 percent (Le8.50 trillion) of the total assets of the financial system. The National Social Security and Insurance Trust (NASSIT) accounts for about 17 percent, Other Financial Institutions (comprising of credit-only MFIs, discount houses, Financial Services Association (FSAs) and Apex bank) about 3 percent and community banks less than 1 percent. Although the contribution of Other Financial Institutions (OFIs) to total assets is relatively small, the implementation of the National Strategy for Financial Inclusion in 2015, designed to accelerate access to financial services, improve the transmission of monetary policy to the real economy and support inclusive growth, has led to a steady increase in their contribution to the financial system. OFIs in recent years have provided crucial services to rural communities that lack access to the formal financial sector thereby facilitating sustainable economic development in the country (Figure 1).

Although Sierra Leone has recorded significant improvements in the banking sector since the financial sector reform started in the 1990s, the sector remains relatively underdeveloped. In terms of GDP, the banking sector assets is on average equivalent to about 26 percent of GDP over the period 2014-2018 (Financial Stability Report 2018). As shown in Figure 2, the total banking assets as a share of gross domestic product grew from 21.23 percent in 2014 to 27.65 percent in 2017 before falling to 26.36 percent in 2018. Figure 2 reflects the trend in banking sector assets as a share of nominal GDP 2014-2018.

![]()

Source: Bank of Sierra Leone.

Figure 1. Assets composition of the Financial System 2014-2018.

![]()

Source: Authors’ computation and Bank of Sierra Leone.

Figure 2. Banking sector assets as a share of nominal GDP 2014-2018 (Percent).

Concentration in the Banking Sector

In spite of the significant growth in the banking system since the financial sector reform, the banking industry in Sierra Leone remained relatively concentrated, with big banks dominating asset and deposits in the industry. The banking sector in Sierra Leone experienced an increase in deposit and asset concentration in 2018, when expressed as a ratio to total assets and total deposits. For the five largest banks in the sector, the banking concentration level increased to 43 per cent and 65 per cent in 2018 from 38 per cent and 64 percent of total assets in 2017, respectively (Financial Stability Report 2018). The share of the three largest banks in total deposits moved from 45 per cent in 2017 to 46 per cent in 2018. A similar trend was observed for the five largest banks with their share to total deposits moving from 67 percent in 2017 to 69 percent in 2018. This development has implications for competition in the Industry as banks with a high asset share may be less sensitive to monetary policy shocks as opposed to small banks that highly depend on borrowing from the central bank. The top five banks, in terms of asset base, controlled 57.03 percent of total banking assets in 2018, up from 52.07 percent in 2012 indicating their significance in the sector (Financial Stability Report 2018).

Structure of the Assets for Commercial Banks in Sierra Leone

As shown in Figure 3, the asset composition of commercial banks remained relatively unchanged over the period 2014-2018. Cash and balances with other banks and investment portfolio continue to dominate the liquid assets of commercial banks accounting for 36 percent and 35 percent respectively of total assets. Loans continue to be moderate contributing on average 19.76 percent over the review period. On the asset side, commercial banks rely heavily on investment in treasury securities and credit to the private sector continued to be subdued.

Structure of Liabilities for Commercial Banks in Sierra Leone

Deposits are the main source of funds for commercial banks accounting for over 80 percent of total liabilities of the banking sector in Sierra Leone over the period 2014 to 2018. This is followed by shareholders’ funds, which accounts for about 13 percent of the total banking sector liabilities and the other liabilities category accounts for the rest. The composition of the banking sector deposits is shown in Figure 4.

Structure of Deposits

In terms of product mix as shown in Figure 5, demand deposits dominate the deposit structure with an average of 64 percent of total deposits, followed by savings deposits with an average of about 26 percent. The dominance of demand deposits in the deposit structure of banks in Sierra Leone may have implications for lending and liquidity management of the commercial banks, as demand deposits are highly volatile. This could be partly responsible for high precautionary reserve holdings in the banking sector in Sierra Leone, which indirectly has

![]()

Source: Authors’ computation and Bank of Sierra Leone.

Figure 3. Structure of assets of commercial banks in Sierra Leone 2014-2018 (Percent).

![]()

Source: Authors’ computation and Bank of Sierra Leone.

Figure 4. Structure of liabilities of commercial banks in Sierra Leone 2014-2018 (Percent).

impacted negatively on the ability of banks to provide long-term funding to productive sectors. Exacerbated by the limited access to offshore credit lines has resulted in lending being skewed towards government, short-term working capital facilities and lending for consumption. This has engendered a vicious cycle of low credit to the productive sector resulting in low underperformance of these sectors and thereby leading to low deposit mobilization from them.

Distribution of Commercial Bank Lending

There has been a significant growth in bank credit over the past decade. However, the bulk of the credit of the banking sector is channeled to the public sector (including state-owned enterprises) and significantly lower share of credit to the private sector, suggesting that the macro-financial landscape in Sierra Leone is characterized by fiscal dominance (Figure 6). In terms of composition, commercial banks invest heavily in Government treasury bills and credit to the private sector is of secondary importance. Around 65 percent of commercial banks’ credit is channeled to the central government while only about 35 percent of credit funds the private sector (Bank of Sierra Leone Annual Report 2018).

![]()

Source: Authors’ computation and Bank of Sierra Leone.

Figure 5. Structure of deposits with commercial banks 2014-2018 (Percent).

![]()

Source: Authors’ computation and Bank of Sierra Leone.

Figure 6. Distribution of commercial bank lending.

2.2. Evolution of the Monetary Policy Framework

Since its inception in 1964, the monetary policy framework and the associated operating procedures of monetary policy of the Bank of Sierra Leone have evolved considerably. The monetary policy strategy can be categorized into two broad phases: the era of direct controls (1964-1992) and the market-based era (1993-date).

Pre-reform Era (1964-1992)

In the pre-reform period (1964-1992), the conduct of monetary policy in Sierra Leone was driven by multiple objectives, which included the provision of cheap credit mainly to state owned enterprises and promotion of economic growth. In addition, the central bank provided significant support to the government’s development goals through direct financing of the government‘s budget. During this period, monetary policy relied mainly on direct monetary control, establishing a ceiling for the expansion of credit by banks, selective sectoral credit allocation, with interest rate guidelines issued to banks and imposing reserve requirements and using moral suasion. The main policy trust was the pursuit of exchange rate stability rather than the control of inflation.

Market-based Era (1993-date)

In the early 1990s, Sierra Leone embarked on a raft of reforms under the World Bank Structural Adjustment Programme. Resultantly, these reforms led to a shift in the macroeconomic and financial policies through the removal of exchange controls regulations on current account transactions, move to a more flexible exchange rate regime replacing the fixed peg, decontrolling interest rates and eliminating credit limits. Furthermore, there were considerable institutional reforms, including the promulgation of new laws and regulations governing the financial sector and the restructuring and privatization of banks. As the financial sector landscape evolved, the Bank of Sierra Leone set in motion a gradual transformation of its monetary policy framework by adopting the monetary targeting framework with a shift from direct instrument to the use of indirect market-based instruments in the conduct of monetary policy. Under this regime, broad monetary aggregate (M2) is used as intermediate target and reserve money as the operating target. The targeted growth in money supply is pursued by setting an intermediate target on the growth of reserve money (RM) which, through a money multiplier, is directly linked to money supply. The target is set for the growth of money supply that is consistent with the projected inflation and real GDP growth. Targets on reserve money are achieved through open market operations conducted through the sale and purchase of government securities and Repurchase Agreements (REPOs) with commercial banks. These operations are complemented with the use of reserve requirements, the Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR), the Liquidity Ratio (LR) and the purchases and sales of foreign exchange as a tool of monetary policy. These instruments are used to influence the quantity-based nominal anchor (monetary aggregates) used for monetary programming. As the economic and financial landscape evolved, the monetary targeting framework was deemed more backward-looking in formulating, implementing, and communicating monetary policy. In this framework, policy analysis focused on recent economic developments rather than underlying or forward-looking pressures that drive inflation. Furthermore, the policy horizon is short, typically focusing on the end-year inflation forecast without a comprehensive assessment of the economic outlook, future risks, the consistency of the policy path with the inflation objective, and contingency plans in the event of large shocks. Given the highlighted drawbacks of this framework, the Bank of Sierra Leone initiated a reform towards a more forward-looking monetary policy framework.

Hybrid framework/Eclectic framework

As the financial sector became more liberalized and more foreign banks entered the commercial banking space and introduced innovative digital products, there were questions in policy circles around the likely instability of the money demand function and the weakening relationship between broad money and inflation, as the association between money aggregates growth and inflation became less than clear (see Figure 7), conditions which are fundamental for the efficacy of the monetary targeting framework. These developments partly motivated the Bank of Sierra Leone to search for an alternative forward-looking monetary policy framework. To this end, the Bank started the move towards modernizing its monetary policy framework by adopting a Hybrid /Eclectic framework.

The first step in the modernization of the monetary policy framework was the introduction of the Monetary Policy Rate (MPR) in February 2011 and narrowing the central bank‘s objective to price stability. One of the motivations for the introduction of the monetary policy rate was to enhance market participants understanding of the monetary policy stance. Under a monetary aggregate targeting framework, it is usually difficult for market participants and other economic agents to understand the central bank‘s monetary policy stance as the monetary aggregates (reserve and broad money) used in conducting monetary

![]()

Source: Authors’ computation and Bank of Sierra Leone.

Figure 7. Inflation and growth in broad money.

policy may convey opaque signals.

This is because price signals (interest rates) are better understood by the market than monetary aggregates. This rate is reviewed every quarter by the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) and has progressively become a tool for the BSL to signal its monetary policy stance. In this case, an increase in the policy rate is a clear indication of the tightening of monetary policy while a reduction in the policy rate signals the loosening of monetary policy. Second, the BSL was accorded operational independence. Meaning, once the inflation target has been set by the Government, the Bank of Sierra Leone had the discretion to use monetary policy instruments at its disposal in managing liquidity conditions with the aim of achieving the inflation target. The other motivations behind the need to modernize the monetary policy framework include strengthening of the monetary policy transmission channel, particularly the interest rate channel; reducing interest rate volatility, which tends to characterize monetary aggregate targeting frameworks; anchoring market expectations with regard to interest rates and inflation; and, promoting transparency in the way banks set the lending rates by making the policy rate the reference rate for pricing of credit products. Finally, the institutional arrangement was enhanced through the introduction of the monetary policy technical committee which was later transformed into the monetary policy committee.

Although the BSL introduced a price-based framework, monetary aggregates are still discussed and agreed in the context of the Extended Credit Facility (ECF) program with the IMF. To achieve reserve money target, the Bank applies monetary policy instruments to influence changes in the level of its lending to banks and central government which together constitutes the Bank’s Net Domestic Assets (NDA). The Bank may also adjust its foreign exchange reserves to influence bankers’ deposits consistent with foreign exchange reserves policy. Thus, in the ECF program, a ceiling is set on the Bank’s NDA and a floor is set on Net Foreign Assets (NFA).

In September 2016, the Bank of Sierra Leone further enhanced its monetary policy operating framework through the introduction of an asymmetric corridor around the monetary policy rate. This was aimed at increasing the efficiency of the transmission of monetary policy and enhancing the transparency and competitiveness of the interbank money market. The corridor consists of the Standing Lending Facility at which the Bank of Sierra Leone will supply liquidity as the lender of last resort and the Standing Deposit Facility at which commercial banks can place excess reserves on an overnight basis. In addition, the introduction of the corridor was aimed at enhancing the effectiveness of monetary policy through better alignment of money market rates, while fostering the development of alternative money market instruments. Under this framework, the success of monetary policy is determined by the strength of the link between the interbank rate and the monetary policy rate. In this context, after five years of implementation of the corridor system, the transmission from the MPR to the

![]()

Source: Bank of Sierra Leone.

Figure 8. Trends in monetary policy and money market rates.

interbank has been supported by a robust liquidity forecasting framework, which has over the years been used to determine optimal market intervention (see Figure 8).

3. Review of Theoretical and Empirical Literature

3.1. Theoretical Foundations

In the theoretical literature, five channels have been identified through which monetary policy impulses are transmitted to the real economy. To better understand the workings of the various channels, we assume that the central bank pursues an expansionary monetary policy by either increasing monetary aggregates under its control or reducing its policy interest rate. A theoretical discussion on each of the channels is presented below:

The Interest rate channel

In the macroeconomic literature, the interest channel has been the traditional channel through which monetary policy impulses are transmitted to the real economy. It relies on the link between changes in the short-term nominal interest rate (induced by changes in the policy rate) and the long-term real interest rate that ultimately affect components of aggregate demand such as consumption and investment in an economy. For example, an expansionary monetary policy leads to a fall in the real interest rate (Keynesian assumption of sticky prices), thus decreasing the cost of capital and stimulating investment, which then results in an increase in aggregate demand. The shift in aggregate demand is eventually reflected in aggregate demand and prices.

The Credit channel

The credit channel explains the impact of monetary policy via the effects of informational asymmetry between the lender and the borrower (Mishkin, 1995). The credit view proposes that as a result of these informational asymmetries, two channels of monetary transmission arise: those that operate through the effects on bank lending as well those that affect the firms and households’ balance sheets. The bank lending channel is based on the assumption that financial intermediaries are best suited to solve problems of informational asymmetry in credit markets while the balance sheet channel is based on the effects of monetary policy on the net worth of firms and hence their collateral. The bank lending channel operates through the influence of monetary policy on the supply of bank loans, that is, the quantity of loans supplied by the commercial banks to firms and households rather than the price of credit. An expansionary monetary policy increases excess reserves in the banking system. This makes loans available to bank dependent economic agents to increase. Increased supply of loans makes it possible for bank dependent economic agents to increase investment as well as consumption spending which result in increased economic activity. This channel is likely to be more effective in economies where there are many small firms with little capacity to raise capital on stock markets. Further, an under-developed capital markets as is the case in most developing or underdeveloped economies makes the bank lending channel stronger. The balance sheet channel operates through the impact of monetary innovations on the net wealth and credit worthiness of households and companies. In other words, like the bank lending channel, wealth effects influence consumption demand through changes in real money balances of households and firms that rely on borrowed funds (Mishkin, 1996).

An expansionary monetary policy increases the net worth of a firm through its cash flows and the value of its collateral, thus leading to a lower external finance premium associated with more severe moral hazard problems. This in turn would increase the level of lending, investment, and output.

The Asset price channel operates through the impact of monetary shocks on yields, equity shares, real estate, and other domestic assets, operating through changes in the market value of corporate and household wealth. A policy-induced change in the nominal interest rate affects the price of bonds and stocks that may change the market value of firms relative to the replacement cost of capital, affecting investment. Moreover, a change in the prices of securities entails a change in wealth which can affect the consumption of households. Mishkin (1995) singles out two main mechanisms through which monetary policy shocks are propagated by changes in equity prices. First, the theory of Tobin’s q suggests that when the value of equities increases relative to the replacement cost of capital, firms would be motivated to issue new equities to purchase investment goods, leading to an increase in investment. Second, equity prices may have substantial wealth effects on consumption because of the permanent income hypothesis. A rise in stock prices increases the value of financial wealth, thus increasing the lifetime resources of households as well as the demand for consumption and output.

The Exchange rate channel

The exchange rate channel is an important transmission channel for small open economies that have adopted a flexible exchange rate regime. The extent to which monetary policy can affect movements in the exchange rate is largely influenced by the theory of uncovered interest rate parity (UIP). Particularly, this channel is concerned with the interrelationships between net private capital inflows and monetary policy following liberalizations in the financial market. In theory, the UIP enables the monetary policy authority to influence the exchange rate, which in turn affects the relative prices of domestic and foreign goods, thus affecting net exports and output. For example, an expansionary monetary policy reduces the domestic real interest rate and this leads to an outflow of capital (i.e., deposits denominated in domestic currency become less attractive compared to deposits denominated in foreign currencies). As a result, domestic currency depreciates and this depreciation of domestic currency makes domestic goods less expensive for foreigners, therefore exports will increase. Simultaneously, imports become expensive and thus domestic imports decline. Overall, an expansionary monetary policy leads to an increase in net exports and aggregate output.

The Expectations channel

This channel is based on the economic agents’ expectations of the future prospects of the economy and likely stance of the monetary policy, given that expectations influence the inflation dynamics. According to this “expectations channel”, most economic variables are determined in a forward-looking manner and are affected by the expected monetary policy actions. Thus, a consistent, credible, and transparent monetary policy can potentially affect the likely path of the economy by simply affecting expectations.

3.2. Some Empirical Considerations

Literature focusing on the application of dynamic panel technique using disaggregated data to capture the relevance of the bank lending channel of monetary policy transmission dates back to 1995 (Kashyap & Stein, 1995). Furthermore, there are recent evidences of the existence of bank lending channel in the context of developing countries (Sichei & Njenga, 2010; Opolot, 2013). Thus, this empirical review will focus mainly on studies that have used bank level data to investigate the bank lending channel of monetary policy transmission.

For instance, Ferri and Kang (1999) examined the existence of the bank lending channel in Korea using a panel of micro-level individual bank data. The result of their study concluded that the bank lending channel played a large role in the transmission of the Korean crises. Based on the quarterly data of US commercial banks from 1976 to 1993, Kashyap and Stein (2000) found that the impact of monetary policy on lending is stronger for banks with less liquid balance sheets. Ehrmann et al. (2001) found the existence of the bank lending channel, with the effects most dependent on the liquidity of the individual banks. In another study, Sengonul and Thorbecke (2005) sought out to evaluate how monetary policy affects bank lending in Turkey using monthly balance sheet data for a sample of 60 banks over the period 1997:01-2001:06. They found that restrictive monetary policy stance significantly impact banks with less liquid balance sheets. By allowing for fixed effects across banks and using GMM method with quarterly data covering the period 1986:1-2001:4, Gambacorta (2005) tried to address the question whether banks react differently to monetary policy shocks in Italy. The study found that the bank lending channel is operative in Italy. Hosono (2006) examined how banks’ responses to monetary policy vary according to their balance sheet using yearly Japanese bank data covering the period 1975-1999. Estimating a fixed bank effect model using GMM two-step method, he found evidence that supports the lending channel for banks that are smaller, less liquid and more abundant with capital. Pruteanu-Podpiera (2007) used a panel of quarterly time series data for 33 Czech commercial banks for the period 1996:1-2001:4 to estimate the effects of monetary policy changes on loans and characteristics of loans supply. The result supports the validity of the bank lending channel. Asbeig and Kassim (2014) examined monetary policy via the bank-financing channel in Malaysia. The finding displays insignificant variances across banks, created on size, capitalization and liquidity levels, and therefore do not support the existence of a bank-financing channel in Malaysia. Farajnezhad & Ramakrishnan (2019) studied the credit channel of monetary policy transmission in Malaysia for the period 2008 to 2017. Using a static panel technique (OLS, random effect model and fixes effect model), the result found evidence of credit channel in the case of Malaysia.

There are few studies from African that have also found evidence of bank lending channel. Sichei (2005) investigated the existence of bank lending channel of monetary policy transmission in South Africa. Sichei regressed the total stock of gross loans on their lag, real GDP, and indicator of monetary policy, a vector of bank characteristics (size and capitalization) and the interaction of monetary policy and the bank characteristics. The findings supported that the joint effect of monetary policy and bank characteristics were statistically significantly and positive, implying banks with stronger balance sheets could cushion the effects of a tight monetary policy on their loan portfolio. Moreover, Sichei and Njenga (2010) investigated existence of bank lending channel in Kenya by using data from banks annual audited balance sheets. They employed an IS/LM model with bank credit. As a measure of capitalization, they used the ratio of excess capital to total risk-weighted assets; and for liquidity, they used the ratio of excess liquid assets to total liabilities. They found that, monetary policy had a more pronounced effect on banks with less liquid balance sheets and on those less capitalized. Chibundu (2009) examined existence of bank lending channel in Nigeria by regressing total loans on its own lag, a measure of policy rate, GDP, inflation and bank characteristics, namely, size, liquidity and capitalization. The results revealed that the bank lending channel for Nigeria was weak. The size and liquidity positions of banks were found to act as a source of information asymmetry that influenced banks’ behavior on loan supply following changes in monetary policy. Opolot (2013) examined the relevance of the bank lending channel of the monetary policy transmission mechanism in Uganda using micro-level data. To capture the impact of bank specific characteristics on the banks’ loan supply function, individual bank characteristics of size, liquidity, and capitalization were also utilized. Using a dynamic panel data framework using a generalized method of moment (GMM) dynamic panel estimator of Arellano and Bond (1991), the study found the presence of the bank lending channel of the monetary policy transmission mechanism in Uganda. In addition, individual bank-characteristics of liquidity and capitalization also plays a significant role in influencing the supply of bank loans.

A number of studies have also examined the importance of different channels of monetary policy transmission in Sierra Leone with contrasting results. Tucker (2005) employed a Vector Autoregressive (VAR) approach to identify the main channels through which monetary policy impulses are transmitted to the real economy. His findings suggested that the exchange rate and credit channels are the most potent channels through which monetary actions impact the real economy. In a study based on a VAR approach, Kadima (2008) estimated monetary policy transmission mechanism in Sierra Leone using monthly data for the period February 2002 to December 2007. His result finds evidence to support the existence of the exchange rate channel in transmitting monetary policy impulses to the real economy, while interest rate and credit channel were found to be insignificant. Ogunkula and Tarawalie (2008) applied a vector error correction (VEC) model for Sierra Leone data for the period 1990Q1 to 2006Q2. The study finds strong evidence that monetary shocks significantly impacted the banking lending channel via private sector credit, ensuring the banks acted as an important conduit for the transmission of monetary policy to the real economy. In addition, the exchange rate channel was found to have a significant effect on inflation with the interest rate channel being insignificant. Lavally and Nyambe (2019) use a Vector Auto regression (VAR) approach to estimate the effectiveness of monetary transmission in Sierra Leone with a focus on the interest rate, exchange rate, and credit channels. The result showed that output responded positively to monetary shocks, as interest rate increase. For exchange rate and private domestic credit, output showed that even in the long run, the effects of the shocks might not be transitory in order to converge towards a steady state. Overall, they concluded that there is evidence of ineffectiveness of the channels of monetary transmission in the Sierra Leone economy.

From the foregoing literature review, there is general conclusion that a tight monetary policy leads to a decline in bank credit (loans), which in turn has a negative impact on the economy and that bank specific characteristics are relevant in gauging banks’ reaction to monetary policy impulses. In addition, few studies have attempted to utilize bank level data to investigate monetary policy transmission in the African context. More importantly in Sierra Leone, there have been a few academic accomplishments made to estimate monetary policy transmission. However, these studies largely relied on the use of aggregate data and use of econometric techniques such as VARs and VECMs. To the authors’ knowledge, so far there is no empirical study that has investigated the transmission mechanism of the monetary policy using bank level data in Sierra Leone. In particular, empirical investigations about the relevance of the bank lending channel for a small open economy like Sierra Leone is lacking, despite the dominance of banks in the financial sector. Therefore, based on this backdrop, this study makes a novel contribution to the existing literature by extending the issue of monetary policy transmission mechanism via the bank lending channel using disaggregated bank-level data. This is the gap this study aims to fill.

4. Methodology and Data

4.1. Model Specification

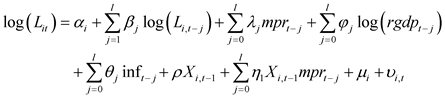

This study follows previous literature on monetary policy transmission using the bank lending channel (see Kashyap and Stein (1995) and Ehrmann et al. (2001)) which has also been utilized by several other researchers in the developing country context e.g. Sichei (2005), Opolot (2013), and Chileshe (2018). Hence, the model is appropriate for analyzing the bank lending channel in a developing country like Sierra Leone. The model is specified as follows:

(1)

(1)

From Equation (1), the supply of bank loans ( ) is determined by lagged dependent variables (

) is determined by lagged dependent variables ( ), monetary policy rate defined by (mpr), gross domestic product (rgdp), inflation (inf), bank specific characteristics (Xi) and the interaction of monetary policy rate and the bank specific characteristics (Xi * mpr). In addition,

), monetary policy rate defined by (mpr), gross domestic product (rgdp), inflation (inf), bank specific characteristics (Xi) and the interaction of monetary policy rate and the bank specific characteristics (Xi * mpr). In addition,  is the bank specific effects, where

is the bank specific effects, where  ~ IID (

~ IID ( ) and

) and  are the remainder error terms, which is

are the remainder error terms, which is .

.

4.2. Estimation Technique

Since the bank lending model presented in Equation (1) includes the lagged dependent variable among the explanatory variables, using a static panel estimation technique (OLS, fixed or random effects) would lead to violation of the strict exogeneity assumption of fixed estimators. According to Nickell (1981), the use of fixed effects estimators for dynamic panel model would produce biased and inconsistent results. In addition, given its dynamic specification, the model is characterized by two sources of persistence over time; autocorrelation due to the presence of a lagged dependent variable among the regressors and bank-specific effects characterizing the heterogeneity among the commercial banks (Baltagi, 2001).

To take account of the dynamic structure of the model and to address the endogeneity problem and inconsistent estimators, we use panel GMM (instrumental variable) estimators. The first, differenced generalized method of moments (GMM) estimator as suggested by Arellano and Bond (1991) has been one of the most popular methods used to address the challenge in estimating dynamic panel data. However, Blundell and Bond (1998) have said that the instruments used in the first difference GMM estimator become less informational and therefore perform poorly. In their 1998 paper, Blundell and Bond suggest the use of System GMM which includes more instrumental variables. In addition, system GMM is designed for dynamic short panels which minimizes the data loss by applying forward orthogonal deviations rather than first difference. System GMM also takes care of endogeneity, heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation. Given the shortcomings of the differenced GMM estimator highlighted above, in this paper we have used Blundell and Bond (1998) system GMM estimators as the preferred estimation method. In addition, Monte Carlo simulations and asymptotic variance calculations by Blundell and Bond (1998) suggest that this extended (System) GMM estimator offers dramatic efficiency gains in the situations where the basic first difference (Arellano & Bond, 1991) GMM estimator performs poorly. Therefore, we use the system GMM approach which maximizes both the consistency in addition to the efficiency of the applied estimator.

Following Zulkefly et al. (2011), this study adopts two techniques to remedy the problem of instruments proliferation. First, not all available lags for instruments are used (for the endogenous variables we used their third to fifth lags as instruments). Macroeconomic variables were assumed to be strictly exogenous and uncorrelated with individual effects; therefore we used their first differences as instruments.). Second, combining instruments through addition into smaller sets by collapsing the block of the instrument matrix. This technique has been used by Calderon et al. (2002), Carkovic and Levine (2005) and Roodman (2009), among others.

To check whether the instruments were chosen properly and the assumptions underlying the model hold, a few tests were proposed (Arellano & Bond, 1991). First, we test the assumption of no serial correlation in error terms. More importantly, we focus on investigating whether second-order serially correlation is absent in the residuals. Under the null hypothesis of no second-order correlation, the statistic associated with this test has a standard-normal distribution. Failure to reject the null hypotheses of both tests confirms the validity of our specifications. Second, we check the validity of the employed instruments with the Sargan test.

4.3. Data Source and Description of Variables

In this paper, quarterly micro-bank level and macroeconomic data spanning 2014-2018 are utilized to test the validity of the bank lending channel of monetary policy transmission in Sierra Leone. The bank level data is sourced from returns of 11 commercial banks out of the 14 licensed banks in Sierra Leone, while macroeconomic variables such as inflation and the monetary policy rate which signal the stance of the monetary policy are extracted from the Bank of Sierra Leone data warehouse. Data on real gross domestic product is sourced from the International Financial Statistics of the IMF. However, since GDP data is compiled on an annual frequency, we utilized the Eviews10 software to convert the “low frequency” time series data to “high frequency” quarterly data using the quadratic match sum method.

There is broad consensus in the theoretical literature on bank lending channel that variables capturing heterogeneity (size, liquidity, capitalization) among banks is important for the observed asymmetric lending behavior of commercial banks. This is even more important for empirical estimation in developing countries (Mishra, Montiel, & Spilimbergo, 2010).

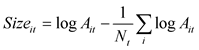

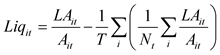

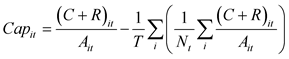

Thus, bank specific characteristics (size, liquidity ratio and capital ratio) included in the empirical estimation of the model are defined as below:

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

Drawing from similar studies on bank lending channel of monetary policy transmission, Size is measured through total assets variable (A). Liquidity is measured by the ratio of liquid assets to total assets (LA variable), and capital adequacy is given by the ratio of capital to total assets (C variable). The three measures are normalized to make the average measure of a characteristic to add up to zero over all the observations.

This allows us to interpret the coefficients of the monetary policy indicator directly as the overall measure of monetary policy effect on loans. It is worth noting that size is normalized with respect to the average of a specific time period, while the other two measures are normalized with respect to the entire sample average.

5. Empirical Results

The results obtained from the empirical estimation of the model are summarized in Table 1. The analysis focused on the results from the two-step system GMM since it presents more statistically significant variables. In addition, Windmeijer (2005) postulated that the two-step GMM performs better than the one-step GMM in estimating coefficient, with lower bias and standard errors. The result revealed that commercial banks’ loan supply in Sierra Leone is jointly explained by past loan supply, economic activity (Real GDP), inflation, monetary policy rate and the interaction term between bank size and monetary policy. The coefficient on lagged loan supply is positive and statistically significant at 1 percent level of significance. The result suggests that loan supply has a tendency to persist over time. The coefficient of the lagged dependent variable is 0.65 indicating the persistence of loan supply in the banking sector in Sierra Leone.

The coefficient for the monetary policy rate is significantly negative, which is

![]()

Table 1. System GMM estimation results of determinants of Bank's Loan Supply Function in Sierra Leone.

Source: Authors’ estimation using STATA16.

consistent with the interest rate channel and shows that bank loan supply falls with tight monetary policy stance. Specifically, a 100 basis point increase (decrease) leads to a 0.43 percent decrease (increase) in loan supply to the economy. This indicates that the bank lending channel is relevant for monetary policy transmission in Sierra Leone and that monetary policy is effective in influencing economic activity through bank balance sheet position, in particular bank loan. This result is expected and is line with study findings by Opolot (2013) who found similar results for Uganda.

The interaction term between monetary policy variable and size has the positive sign and is statistically significant. The positive sign of the interaction term with size is consistent with the theoretical explanation of the bank lending channel, which assumes that lending volumes of larger banks are less sensitive to monetary policy conditions than that for smaller banks. This result also supports the prediction of Kashyap and Stein (1995) that the lending volumes of smaller banks are more sensitive to monetary policy than that of larger banks. This effectively confirms the presence of bank lending channel in Sierra Leone. However, the interaction between monetary policy and bank capital and liquidity have an unexpected negative sign and are statistically insignificant in explaining the supply of bank loans. The statistical insignificance of the interaction term with capital and liquidity suggest that bank capital and liquidity are not a source of asymmetric response of banks to monetary policy stance.

Turning to macroeconomic variables, the result indicates that macroeconomic variables are critical in the loan supply function of Sierra Leone. The coefficient of real GDP is significant and has the expected positive sign. Implying that growth in real GDP growth raises lending, which is suggestive of procyclicality in banks’ credit extension behavior. This is consistent with expectation since a booming economy would tend to have many economic agents with excess savings, which commercial banks can mobilize to extend credit. Specifically, an increase in economic activity by 1 percent would lead to an increase in loan supply by 0.22 percent. Inflation is also significant in explaining loan supply in the Sierra Leone economy but with a negative sign.

This could be partly explained by the fact that the central bank usually responds to inflation by tightening the monetary policy stance. This is therefore expected to affect the commercial banks loan supply contemporaneously.

In order to test the validity of our study, we conducted robustness checks on instrument validity and second order autocorrelation. The test of over-identifying restrictions (i.e. Sargan test) cannot reject the null hypothesis that the instruments are uncorrelated with the error term. In addition, we can reject the null hypothesis of no first order autocorrelation, but it is not possible to reject the null hypothesis of no second order autocorrelation. In conclusion, these tests taken together, suggest that the model is well specified.

6. Conclusion and Policy Recommendation

This paper is the first attempt at estimating monetary policy transmission in Sierra Leone using bank level data. Conducting a micro-level analysis, this paper attempts to find out whether banks’ loan supply adjust to monetary policy shocks and whether banks’ reaction to monetary policy differs depending on certain bank specific characteristics like size, liquidity and capitalization of a bank. In addition, the paper further investigates how loan supply adjusts to macroeconomic shocks (real gross domestic product and inflation). The data cover bank level data and macroeconomic variables during the period 2014 to 2018.

The result revealed that in Sierra Leone, commercial banks’ loan supply is jointly explained by past loan supply, economic activity (Real GDP), inflation, monetary policy rate and the interaction term between bank size and monetary policy. Specifically, the findings suggest that, the coefficient of the policy rate is negative and statistically significant, as expected. These findings lend support to the hypotheses that, bank lending channel operates in Sierra Leone, suggesting that bank loans are important channel through which monetary policy shocks are transmitted to the economy. The findings are consistent with the stylized facts that the banking sector still dominates the financial system in Sierra Leone.

In addition, monetary policy in Sierra Leone can be propagated by the banking sector, depending on the size of the bank. The interaction term between monetary policy variable and size has the positive sign and is statistically significant. The positive sign of the interaction term with size is consistent with the theoretical explanation of the bank lending channel, which assumes that lending volumes of larger banks are less sensitive to monetary policy conditions than those for smaller banks. This further confirms the presence of bank lending channel in Sierra Leone. Finally, real GDP is significant and has the expected positive sign. This is consistent with expectation since a booming economy would tend to have many economic agents with excess savings, whose commercial banks can mobilize to extend credit. Inflation is also significant and has a depressing impact on loan supply. This could be partly explained by the fact that the central bank usually responds to inflation by tightening the monetary policy stance. This is therefore expected to affect the commercial banks loan supply contemporaneously.

The main policy implications from this study are that since bigger banks are able to insulate their loan portfolio from monetary contraction, the Bank of Sierra Leone should monitor the micro-dynamics of individual bank behavior in order to enhance the efficacy of monetary policy impact on the real sector in Sierra Leone. In addition, the information on the banking sector could be used as an input to form judgment about the likely impact of future interest rate changes on the economy.