Factors Associated with Tobacco Use among Community Dwelling Older Adults in Jos South, Nigeria ()

1. Introduction

Tobacco use poses an enormous threat to public health worldwide, killing more than eight million people every year [1].

It has been predicted that tobacco will kill one billion (1,000,000,000) people this century, if nothing is done in the form of prevention. It is the world’s leading preventable killer, driving an epidemic of cancer, heart disease, stroke, chronic lung disease and other non-communicable diseases. The health hazards are well documented [1] - [6].

While the disease burden of tobacco is higher in Europe and South East Asia as against Alcohol which is known to have largest burden in Africa, the Americas and Western Pacific, it causes enough preventable death to warrant attention [7].

Although the developing countries still have to grapple with infectious and communicable diseases, Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) cause more than two thirds of deaths in developing countries, and tobacco use is a major risk factor for NCDs such as cancer and heart disease [1]. It seems that the tobacco epidemic is shifting to the developing world, where less well-resourced countries find themselves unable to counter tobacco industry exploitation of new markets, often through blatant interference with public health policy-making [1].

In Nigeria, more than 16,100 people are killed by tobacco-caused disease annually [6]. Still, more than 25,000 children (10 - 14 years old) and 7 488,000 adults (15+ years old) continue to use tobacco each day. Notwithstanding that on the average as compared to other low-HDI countries, fewer men and women in Nigeria smoke, yet more than 7,086,300 men (13.7%), 402,600 women (0.8%), 19,500 boys (0.17%) and 6100 girls (0.06%) who smoke cigarettes each day, making it an ongoing and dire public health threat [4].

Similarly, on the average fewer men 246 (1.75%) every week, fewer women 64 every week (0.53%) die from Tobacco in Nigeria as compared on average to other low-HDI countries, and these deaths are huge enough to require action from policy makers.

Although economic costs of smoking in Nigeria are not known, the total economic cost of smoking globally amounts to 2 trillion dollars, when adjusted for 2016 purchasing power parity (PPP). This includes direct costs related to health care expenditures and indirect costs related to lost productivity due to early mortality and morbidity [4].

Successful aging includes three main components: low probability of disease and disease-related disability, high cognitive and physical functional capacity, and active engagement with life. All three terms are relative and the relationship among them is to some extent hierarchical. Successful aging is more than absence of disease, important though that is, and more than the maintenance of functional capacities, important as it is. Both are important components of successful aging, but it is their combination with active engagement with life that represents the concept of successful aging most fully [2].

As individuals age, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) become the leading causes of morbidity, disability and mortality in all regions of the world, including in developing countries [8].

NCDs, which are essentially diseases of later life, are costly to individuals, families and the public purse. But many NCDs are preventable or can be postponed. Failing to prevent or manage the growth of NCDs appropriately will result in enormous human and social costs that will absorb a disproportionate amount of resources, which could have been used to address the health problems of other age groups [8].

Studies on smoking and tobacco use in Nigeria have been more on youths and general adult population. [9] [10] [11] [12]. We therefore set out to determine the factors associated with tobacco use and use disorders among the community dwelling elderly in Jos South LGA, Plateau State, Nigeria.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design

A community based cross-sectional survey.

2.2. Study Setting

Kuru is a conglomerate of several villages and hamlets located about 20 km to Jos, the capital of Plateau State. While Hausa is generally spoken and is the language of business, the indigenous language spoken in Jos South is Berom, the name by which the ethnic group is called. The estimated population of Kuru in the last National Population censors of 2006 was 36,054. The predominant occupation of the town’s residents is farming.

The study was part of a larger project examining alcohol and other psychoactive substance use and disorders among community-dwelling elderly population in the context of a general health survey.

2.3. Participants

The study population comprised of elderly men and women, aged 60 years and above residing in Kuru, Jos South Local government, Plateau State, Nigeria, at least not less than 6 months preceding the commencement of the study. Elderly Patients who are too acutely ill to get into meaningful clinical engagement were excluded from the study.

2.4. Sampling/Sample Size

Using a prevalence of 45.2% = 0.452 [13] and absolute standard error of 0.05 and standard normal variance of 1.96, a minimum sample of 381 was calculated using appropriate formula for proportions but increased to 419, to allow for a 10% non-response or attrition rate [14].

Kuru was purposively selected based on anecdotal reports of high rates of use of alcohol and other psychoactive substances by her residents. However, there was no documented study on the rate of use and its effects in the community.

According to data obtained from the office of National Population Commission in Jos from the last censor conducted in 2006, the estimated population of the elderly 60 years and above in Kuru was 1530.

A total house mapping of the community was done to identify all the houses where the elderly resides. Subsequently, all elderly members of the community who met the inclusion criteria and gave consent were recruited into the study until the sample size was achieved. Using the above process, a total of 422 elderly community dwellers were identified. Out of this number, 16 declined consent and 3 were too ill to respond while 3 others gave very scanty information that their responses could not be used leaving 400 participants analyzed.

Data collection was with the aid of a composite questionnaire which was administered by interviewers. The questionnaire was translated to Hausa language and back translated to the English language by two professionals (a linguist and a psychiatrist) fluent in English and Hausa, so as to ensure content validity of the tool.

2.5. Instruments

Socio-demographic questionnaire capturing gender, age, education, income (personal and family), work/occupation (including current regular professional work, other occupations in retirement, non-professional work, voluntary), ethnicity, religion, marital status, living status.

· Social Network (existence of a person who participant can count on in difficult moments)

· Lifestyle, physical activity, self-reported health status

· History of chronic physical or mental illness

· Functional status: assessed by a five-item scale eliciting basic household independency, ability to take medicines, bathe/comb hair/dress, ability to eat without support, and physical functioning—walk, sit, lie down, get around indoors, and go upstairs.

· Use of health service: number of doctor visits in the last 12 months and/or hospitalizations in the last 12 months.

General Health Questionnaire 12-item The GHQ-12 was chosen because of its brevity and ease of completion. The validity of the GHQ-12 has been reported to be comparable with that of the longer versions of the GHQ in the identification of minor psychiatric disorders. For the purpose of this study, the GHQ scoring method (0-0-1-1) was chosen over the simple Likert scale of 0-1-2-3, as this particular method is believed to help eliminate any biases which might result from the respondents who tend to choose responses 1 and 4 or 2 and 3, respectively [15]. The GHQ-12 had been previously validated [16] and extensively used in Nigeria [17] [18].

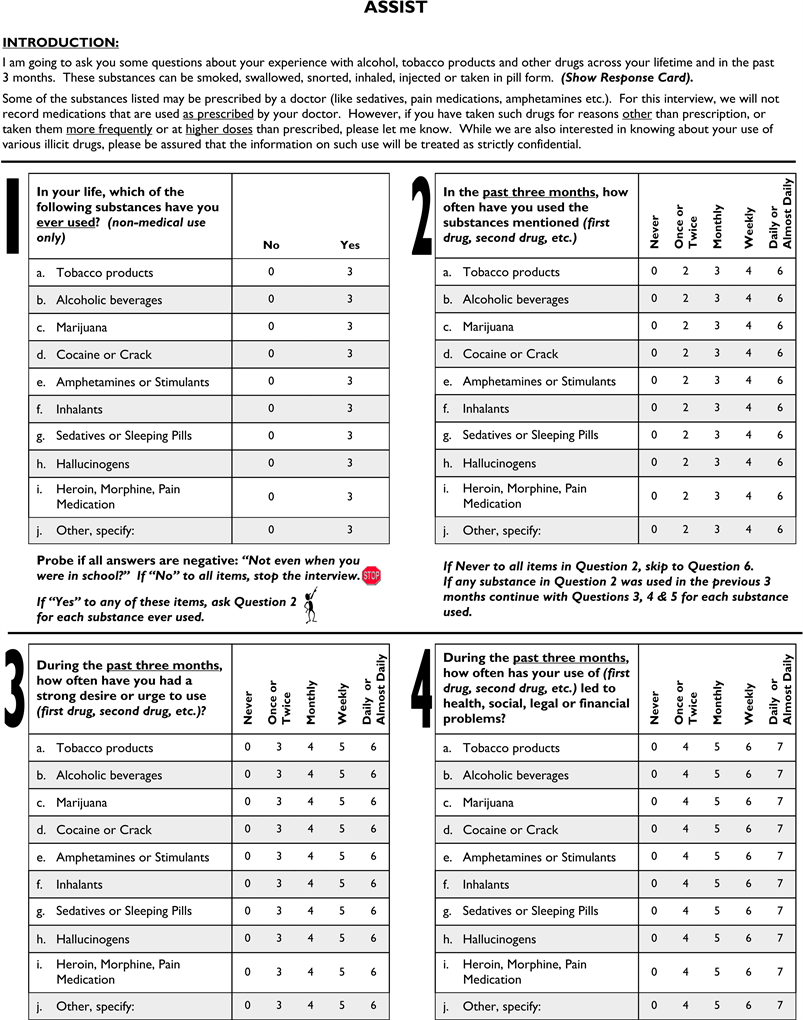

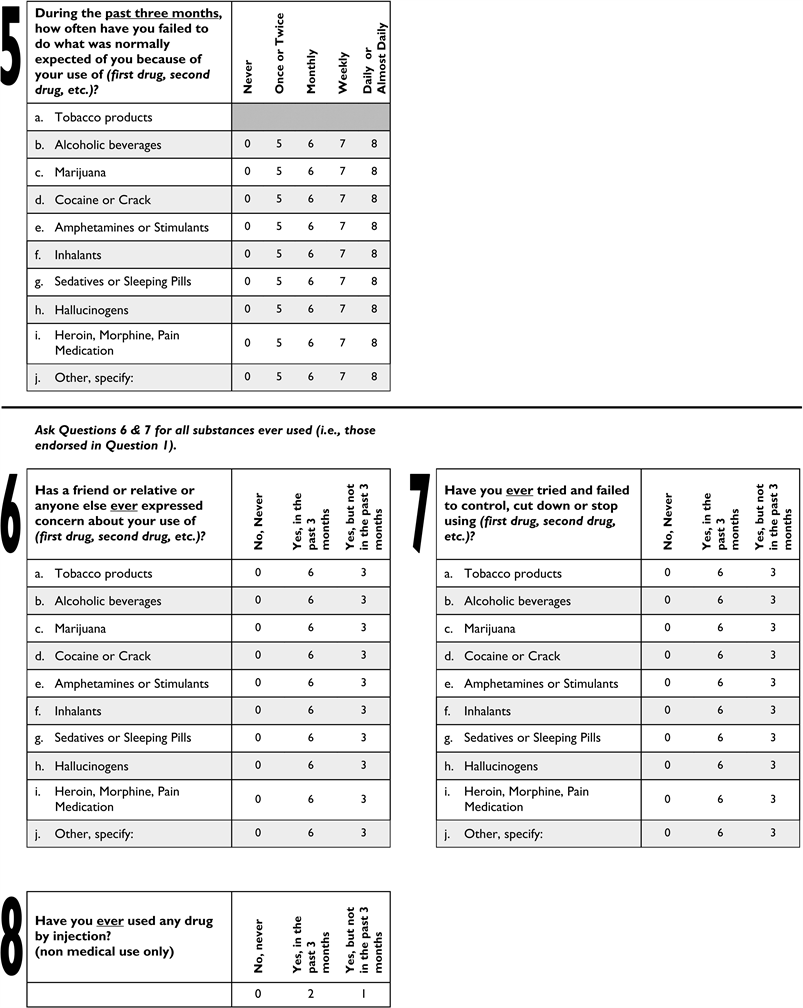

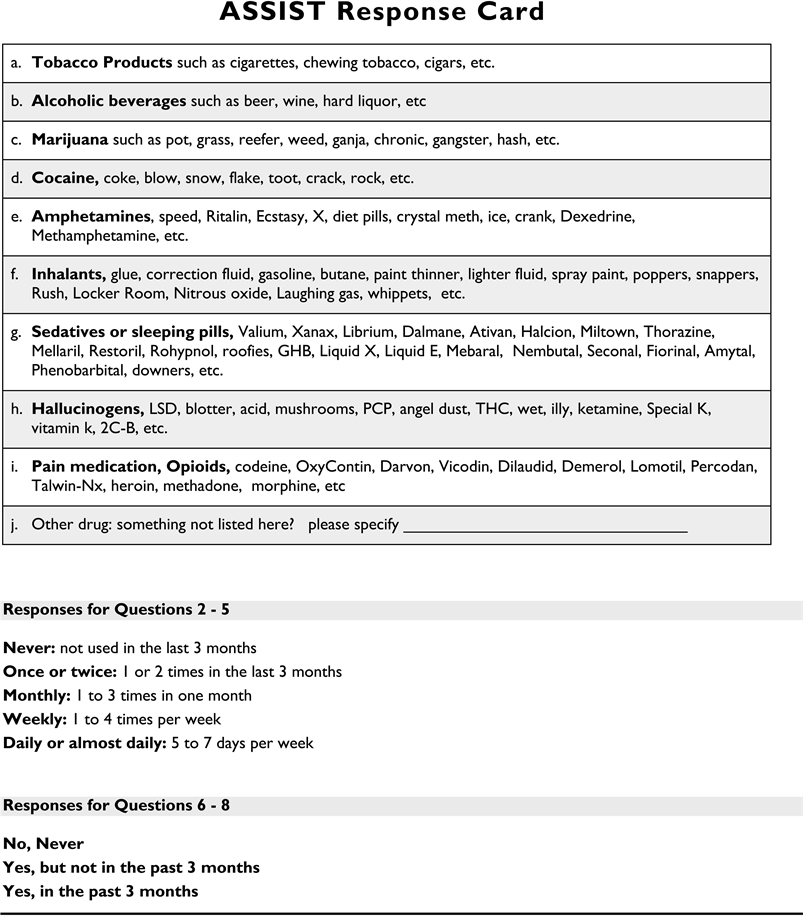

The Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): The ASSIST was developed by the World Health Organization for screening in primary and general medical care settings and has since been considered as an instrument of choice when the goal is to address a range of different psychoactive substances [19]. The instrument asks about lifetime use of substances (lifetime or ever used) or current use (in the last three months). This test categorizes respondent’s substance use into low, moderate and high risks on the bases of their scores. With scores of 0 - 10 for alcohol and 0 - 3 for illicit drugs, participants are considered as having low risk for health and other problems from their use of alcohol and other drugs (AODs), 11 - 26 for alcohol and 4 - 26 for other drugs indicate moderate risks while >26 indicates high risk for health and other problems from their current use of alcohol and other drugs and are likely to be dependent. The ASSIST was used in a previous study and took an average of 3.85 - 6 minutes to administer to the research participants [20].

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Drugs Sections): The MINI was used in this study. Responses were rated at the right of each question by circling either “Yes” or “No”. The MINI is a short structured clinical interview that helps researchers to make diagnoses of psychiatric disorders according to DSM-IV or ICD-10. The MINI was designed for epidemiological studies and clinical trials and is divided into modules identified by letters, each corresponding to a diagnostic category [21]. At the beginning of each diagnostic module, screening question (s) are made to the corresponding main criteria of the disorder, after which diagnostic box(es) permit the clinician to indicate whether the diagnostic criteria are met. This module took approximately 1 - 2 minutes to administer in this study.

The ASSIST Feedback Report Card was used in this study to provide substance-specific involvement scores based on calculated standard ASSIST scoring procedures. The scores ranged from 0 - 10 = low, 11 - 26 = moderate, and 27+ = high. Research participants within the low score range on the ASSIST are interpreted as being at “low” risk of health and other problems related to substance use. Finally, participants whose scores falls within the “moderate-high” range will be evaluated as being at “moderate-high” risk of experiencing severe problems as a result of their current use and are likely dependent on the psychoactive substance.

2.6. Data Collection

A total of eight (8) trained research assistants; psychologists, social workers and interns were involved in the data collection which took place from 17th to 31st August, 2018. They were previously trained in the content and administration of the components of the questionnaire. They also got acquainted with the objectives of the study and on how to conduct the interview in a non-judgmental way. The research assistants could speak English, Hausa and Berom. Pretesting of the questionnaire was conducted among elderly people in another community but of the same ethnicity and characteristics as the study setting. This enabled us to detect and correct minor ambiguities and to ascertain the average time of administration of the questionnaire.

2.7. Data Analysis

Data was analyzed using SPSS version 23 statistical software after imputing into an excel sheet and exporting to the SPSS. The dependent variable was substance use/disorder (present/absent). Independent variables were: socio-demographic characteristics, social network, self-reported health status, psychiatric morbidity and use of health services.

Frequencies and percentages were used to calculate the prevalence of psychoactive substance use/disorders. The Chi-squared test categorical associations with level of significance set at p < 0.05.

2.8. Ethical Consideration

Approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Jos University Teaching Hospital (JUTH). Permission was sought from the district head of Kuru after explaining the nature and purpose of the study. Due to limited formal education in most of the cohort, the purpose of the study was read out to participants in the presence of a significant other, and informed verbal consent or thumb-printed signed forms were obtained.

All participants who screened positive on ASSIST and those diagnosed with SUDs on Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) were counseled adequately, given brief intervention or referred to the Psychiatry clinic of the hospital for management as the case may be.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

A total of 400 out of a total of 422 elderly community dwellers identified were interviewed.

Elderly males were in the minority (n = 158; 39.5%), but most were aged between the 60 - 69 years’ age group (n = 249; 62.3%) with a mean age of 69.19 years. Most lived with a family member or other close relative (n = 389; 97.2%). Majority of respondents were married (230, 57.5%) and a total of 157 (39.3%) respondents were widowed.

Over half (59%) had no formal education, but nearly half had regular or occasional employment (n = 198; 49.5%). Majority of the respondents (n = 235, 58.8%) were farmers. Seventy-nine percent of respondents earned between N1000 to N10,000 and only 12.8 % (n = 51) earned above N21,000. See Table 1.

![]()

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants.

3.2. Clinical Characteristics

Over a third (36.0%) reported their current health status as “very good”. While a majority of participants reported having a chronic pain condition (n = 267, 66.8%), those with cardiovascular (n = 58, 14.5%), respiratory (n = 15, 3.8%), digestive (n = 172, 43%) conditions were in the minority. Over half screened positive on the GHQ-12 with probable psychiatric morbidity (n = 224, 56.0%). See Table 2.

3.3. Prevalence and Correlates of Tobacco Use

The lifetime and current prevalence of tobacco use were 17.5% and 15.8% respectively. See Table 3.

![]()

Table 2. Clinical related characteristics of participants.

![]()

Table 3. Prevalence of tobacco use and use disorder among participants.

Tobacco use disorders was not significantly associated with gender (X2 = 0.10, p < 0.75), or living status (p = 0.22).

Participants who used tobacco were more likely to report cardiovascular (X2 = 0.03, p = 0.96), respiratory (X2 = 0.21, p = 0.65), digestive (X2 = 3.86, p = 0.05), difficulty ambulating (X2 = 0.34, 0.56), probable psychiatric co-morbidity (X2 = 0.12, p = 0.72) and chronic pain conditions (X2 = 0.74, p = 0.39), and have more hospital visits (X2 = 1.18, p = 0.40), and admissions (X2 = 0.03, p = 0.96) but the relationships did not attain statistical significance.

4. Discussion

The small difference between the lifetime prevalence of tobacco use (17.5%) and the prevalence of current use (15.8%) could be due to the fact that tobacco is considered to be one of the most addictive substances of abuse making it more difficult for smokers to quit even with increasing age. This contrasts greatly with the marked decline in the prevalence of current alcohol use (45.5%) as against the lifetime use (69.8%) seen in the same population [22]. The prevalence of current use of 15.8% is similar to that obtained in a previous study in Malaysia where the prevalence of current smokers was 15.2%. However, the lifetime prevalence of 17.5% was markedly different from 28.3% (current smokers plus ex-smokers of 13.1%) in that study [3].

Another study has also not found significant decline in the prevalence of use of tobacco with advancing age [23].

The lifetime prevalence rate of 15.8% was not markedly different from the prevalence rate of 13.3% found among participants of a community outreach programme in Jos North Local government, a neighboring local government to the present study site [20].

In the study conducted by Gureje et al. among people in 21 out of 36 states in Nigeria, they reported a lifetime use of Tobacco of 29.7% among older adults 65 years and above. There was also a decline to only 2.2% when the last 12 month was used to calculate the current prevalence of use [24].

Nicotine dependence may be more severe in old smokers compared to young smokers. The motivation to quit smoking may be also different between old people and young adults.

Tobacco use disorders was not significantly associated with gender (X2 = 0.10, p < 0.75), or living status (p = 0.22). This is contrary to previous similar studies which found that males, being married and lower educational status were associated with smoking [3] [23] [25]. This is also contrary to what obtains in the adolescents and younger adults where tobacco use is associated with male gender in particular [9] [12] [26].

However in a study among outdoor smokers in Nigeria, the authors found that age, sex, employment, marital status, and income level were not associated with smoking just like in this study [11]. We also noted in our study that elderly males were in the minority (n = 158; 39.5%), among the respondents as compared with females. This may be because males might have died before reaching the age of 60 years which is the age for inclusion in the study. This may be a plausible explanation for sex and other demographic variables not being associated with tobacco use in this elderly population.

Literature supports that tobacco use affects older adults by exacerbating existing diseases, causing poorer physical functioning, increasing functional impairments, increasing psychiatric morbidities and increasing mortality due to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases [27] [28] [29]. Similarly we found that participants who used tobacco were more likely to report cardiovascular (X2 = 0.03, p = 0.96), respiratory (X2 = 0.21, p = 0.65), digestive (X2 = 3.86, p = 0.05), difficulty ambulating (X2 = 0.34, 0.56), probable psychiatric co-morbidity (X2 = 0.12, p = 0.72) and chronic pain conditions (X2 = 0.74, p = 0.39). We also found that they have more hospital visits (X2 = 1.18, p = 0.40), and admissions (X2 = 0.03, p = 0.96) which means that there is increase in health care consumptions with attendant strain on health care resources and cost. However none of these relationships attained statistical significance.

The study is limited by a number of factors. Firstly, there was no distinguishing the different types of tobacco products; cigarette, snuff and chewing tobacco. Secondly, the cross sectional design at best shows association but cannot confirm causality. Thirdly, the screening instrument, ASSIST and diagnostic instrument MINI were all based on self-reports and participants could have denied the use of tobacco and other substances and their complications when actually they do. There may also be recollection bias.

Lastly, self-report of chronic health conditions might have been affected by a lack of awareness of the presence of a particular health problem by the participants.

5. Conclusion

We conclude that tobacco use is highly prevalent among older adults living in the community. While there is a slight difference between the lifetime prevalence and current prevalence among participants, the difference is too slight and gives reason for concern about the presence of cessation programs for the elderly or the effectiveness of such if indeed it is present.

6. Recommendation

We recommend a more aggressive attitude toward designing and implementing tobacco smoking cessation programs so as to prevent avoidable death and improve the quality of life.

Tobacco control advocates must reach out to other communities and resources to strengthen their efforts and create change.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Center (FIC); Office of the Director (OD/NIH); National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS/NIH); and the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR/NIH) of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number. D43 TW010130.

Acknowledgements

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health.

We also like to acknowledge the staff of Netwealth Centre for Addiction Management and Psychological Medicine, Rantya, Jos, Plateau State Nigeria for the data collection and providing Brief Intervention where appropriate.

Appendix I

Section 1 Socio-demographic Questionnaire S/No…………..

1. Sex _______________________

2. Age (in years) ____________________

3. Religion: 1.Islam………. 2. Christianity……… 3.Traditional………. 4. No Religion…… 5. Others (Specify)________________

4. Nationality: Nigerian…………. Others (Specify)________________

5. State _________________________

6. Ethnicity/Tribe _________________________

7. Living status: Alone?

(a) Yes o (b) No o

With whom: 1. With spouse/partner o 2. family or relatives o 3.With friends (no family relation) o 4. With children (no spouse) o 5. Other o (specify)____

8. Marital status: 1. Single (never married) o 2. Married o 3. Divorced/separated o 4. Widowed 5. Other o (specify) ________

9. Highest educational level completed:

1. Some (Never completed) primary school o

2. Completed primary school o 3. Some secondary school o

4. Completed secondary school o 5. Some tertiary/graduate o

6. Completed tertiary/graduate o

10. Employment status (last 30 days):

1. Regular employment o 2. Occasionally employed o

3. Volunteering o 4. Unemployed o

5. Housewife o 6. Retired o Others

11. Exact Occupation (Please be specific)___________________________

12. Monthly income_______________________

Section 2: Physical Health Status

13. How is your health? 1. Very good, 2. Good 3. Regular. 4. Bad 5. Very bad

14. Has your doctor told you that you have any of the following?

a. Vascular Conditions: 1. Hypertension 2. Heart Disease.

3. Diabetes 4. Stroke, 5. Vericose Vein

b. Respiratory Conditions 1. Bronchitis 2. Pneumonia 3. Asthma

4. Tuberculosis 5. Others

c. digestive conditions 1. Irritable bowel syndrome 2. Ulcer

d. chronic pain: 1. back Pain 2. neck pain, 3. arthritis,

4. frequent headaches

5. chronic pain in any other body parts

e. Bone Fracture (By minimal Trauma)

f. Others: 1. Cancer 2. Epilepsy 3. Kidney disease

15. Functional Status: Describe how best you can do the following activities.

a) without difficulty b) with some difficulty, c) only with assistance, d) unable to do

i. Cleaning (domestic)

ii. Maintenance (house)

iii. Cooking

iv. Taking Medicine

v. Bathe

vi. Comb Hair

vii. Dress

viii. Eat

ix. Physical Func (Ambulation)

16. Use of Health Services

a. No of visit to the doctor in the last 12 months

b. No of hospital admissions in the last 12 month

Section 3. Mental Health Status

Have you recently?

Appendix II