A Pragmatic Study of Strategic Maneuvering in Selected Political Interviews ()

1. Introduction

Undoubtedly, argumentative practices appear to be closely related to the specifics of human language and communication ( Bermejo-Luque, 2011: p. 2 ). Pragmatics is distinguished as the discipline of strategies, intentions and speakers’ conveyed meaning. Pragmatics is interested in the way meanings can be inferred from conversational acts. Justification, constitutive and regulative constraints used to decide good argumentation turn out to be linked to pragmatic conditions that make a given piece of behavior an attempt at showing illocutionary aspect of a claim to be correct ( Bermejo-Luque, 2011: p. 53 ).

Hence, the researcher will shed light on related pragmatic issues: speech act, hedges of the cooperative maxims, conversational implicatures, and politeness for their indispensable contribution in explaining and understanding the process of strategic maneuvering in the analysis of the data in this study.

According to Wodak (2007: p. 203) various pragmatic devices such as presuppositions, implicatures, speech acts, etc. can be analyzed in their multiple functions in political discourse where they frequently serve interviewers and interviewees certain goals.

Put differently, the role of pragmatics can emerge in revealing the real intentions of the speaker that are sometimes obscure, and thus, may lead to a sense of misunderstanding on the part of the listener. As a result, as the case in politics, the political outcomes can be unaccepted. However, it should be stressed that some specific pragmatic aspects occupy mostly the core of political discourse as in the case with the use of speech acts, implicatures, etc. Malmkjar (1991: p. 476) defines pragmatics as “the study of rules and principles which govern language in use”.

The concept of strategic maneuvering has been defined by van Eemeren and Houtlosser as:

The balancing of people’s resolution-minded objective with the rhetorical objective of having their own position accepted regularly gives rise to strategic manoeuvring as they seek to fulfill their dialectal objectives without sacrificing their rhetorical potentialities ( Van Eemeren & Houtlosser, 2000: p. 1 ).

In trying to balance both interests, in a genre (political interview) which is completely argumentative ( Lauerbach, 2007: p. 1394 ), the participants to a discussion engage in strategic maneuvering ( van Eemeren & Houtlosser 2000, 2002, 2003 ; van Eemeren, 2010 ).

Strategic maneuvering can be appropriately explicated with reference to Leech’s (1983) interpersonal rhetoric model which brings pragmatics and rhetorics together. According to Leech (1983: p. 16) conversational cooperation maxims and politeness are required beside rhetorical pragmatic strategies such as irony, overstatement, understatement, etc. to preserve a successful conversation. He adds Leech (1983: p. 56) that the interpersonal function influences the attitudes of the hearer. Plus, he moves to say Leech (1983: p. 149) that rhetorical devices as irony, overstatement, understatement, etc. can be integrated into the Gricean conversational principles and implicatures, thereby helping in ways to complement the maxims of the CP and the PP. Put differently, Leech’s interpersonal rhetoric includes interpersonal role of cooperative principle, the interpersonal role of politeness principle, that of the irony principle, and etc. Leech (1983: p. 15) . This means that exploiting the Gricean maxims generates conversational implicatures which may be utilized by the interviewee to maintain the exchange, resorting to politeness strategies to sustain interaction and rhetorical tropes to strengthen the strategic maneuvering.

This is because the pragmatic components of this speech genre, viz. political interviews and the pragmatic strategies employed for realizing them have not been fully investigated by other researches. Consequently, the present study makes its appeal to tackle strategic maneuvering from this angle. This study concerns itself with a purely pragmatic approach to strategic maneuvering. Precisely, this study attempts to shed light on the most problematic areas in political maneuvering. These fuzzy areas must be delineated and made clear because they impinge upon understanding how political speeches appeal themselves to the readers and how in turn these readers could find out the impetus behind these maneuvering. As such, the problem of this study is to be dressed in the form of the following questions:

1. What is the pragmatic structure of strategic maneuvering?

2. What are the most common pragmatic strategies employed by the interviewer at the initiating stage of the process of strategic maneuvering?

3. What are the most common pragmatic strategies exploited by the interviewee at the response stage in the interviews selected?

4. What are the most common pragmatic strategies utilized by the interviewer at the evaluation stage in the selected interviews?

5. What are the pragmatic strategies manipulated by the interviewers and the interviewees to achieve each of the aspects of strategic maneuvering i.e. topic potential, audience demand, and presentational devices?

The present study aims at investigating the concept of strategic maneuvering, its strategies, and processing stages when dealing with it from a pragmatic perspective in political interviews. It also develops a model for the analysis of strategic maneuvering pragmatically in political interviews.

To achieve the above mentioned aims, it is hypothesized that: speakers tend to use particular strategies more than others to express strategic maneuvering in the political interviews selected. To reach out strategic maneuvering, three stages of the process should be taken into account: initiating, response, and evaluation stages.

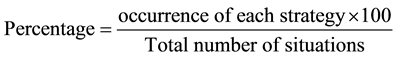

Some procedures are introduced to establish a general view of the phenomenon in question: Reviewing the literature about strategic maneuvering, its definition, related theories, etc., collecting data from political American figures, analyzing the strategic maneuvering situations in the political interviews selected by means of the model which is developed for this purpose, and using a mathematical statistical method, represented by the percentage equation, to calculate the results of the analysis and statistically verify findings of the analysis.

This study is limited to investigating strategic maneuvering in terms of certain pragmatic strategies, i.e., speech act, hedges of the cooperative maxims, conversational implicatures, and politeness. It seeks its aims in all the strategic maneuvering situations in a number of randomly selected political interviews between 2002 and 2009. These interviews have been found representative to what is required by the data of the study.

2. Strategic Maneuvering: Literature Review

This section is concerned with reviewing the literature related to strategic maneuvering. It provides a theoretical background about the three inseparable aspects of this concept. It will also shed light on the pragmatic issues relevant to attain strategic maneuvering in the domain of political interviews. They are all summarized below.

2.1. Definition of Strategic Maneuvering

Van Eemeren and Houtlosser’s concept of strategic maneuvering has three “inseparable” aspects: “… in trying to be effective, an arguer naturally summons the best available arguments, considers their acceptability with the audience addressed, and tries to present or frame them in the best way possible given the outcome desired” ( van Eemeren, 2010: pp. 98-99 ).

The Amsterdam School has made attempts to extend the pragma-dialectical theory by reconciling the dialectical perspective with rhetorical insights. For this purpose, they developed the concept of strategic maneuvering, which helps understand the relationship between the arguers’ complying with dialectical obligations and their aiming to achieve rhetorical effectiveness by means of persuasive argumentative moves ( van Eemeren, 2010 ; van Eemeren et al., 2012 ).

Maneuvering comes from the verb “maneuver”, which has performing maneuvers as its first meaning. The noun “maneuver” can refer to a planned movement or a movement to win or do something.

The term strategic is added to maneuvering because the goal aimed for in the maneuvering has to be reached by a skilful planning, doing optimal balance between reasonableness and effectiveness. To Drucker (1974) , strategy is purposeful action; to Moore (1959) design for action, in essence, conception preceding action.

According to Eemeren et al., the tools used in maintaining the balance between effectiveness and reasonableness may be referred to as (argumentative) “techniques”. This means that there is a communicative gap between a dialectical approach and a rhetorical approach to the study of argumentation (cf. Leeman, 1992 ; Toulmin, 2001 ). Bridging the gap is by using these pragmatic techniques, and showing that rhetorical and dialectical approaches are, in fact, complementary from the perspective that both aim at persuasion (cf. Krabbe, 2002 ; Leff, 2002 ).

The concept of strategic maneuvering can be used to understand how the arguers’ various choices contribute to achieve reasonableness while trying to obtain at the same time an advantageous outcome of the discussion. Reasonableness is truth seeking according to Aristotle. To obtain advantageous outcome of the discussion, arguers tries to be effective. By making use of this concept, the analysis of an arguers’ argumentation does explain both the dialectical interest in maintaining reasonableness and the rhetorical interest in being effective ( van Eemeren & Houtlosser, 2000, 2002, 2003 ; van Eemeren, 2010 ).

As far as pragmatics is concerned, Jacobs (2002) states that normative pragmatics conceptualizes argumentative effectiveness in a way that integrates notions of rhetorical strategy with dialectical norms. He also adds that all arguments involve rhetorical strategies and all rhetorical strategies involve language use. And all language use is organized by inferential and strategic principles―the domain of pragmatics.

As to Riker (1986) , strategic maneuvering is important in politics to win a point by means of an argument. To Renkema (2009) , Strategic maneuvering means that in all stages of a critical discussion, from confrontation to conclusion, the participants resort to the best rhetorical result. The arguers make use of strategic maneuvering aimed at reducing the potential tension between the two endeavors: effectiveness and reasonableness. To Kennedy’s (2007: p. 27) , even those who just try to establish what is just and true need the help of rhetoric when they are faced with a public audience. To express a communicative intention, effectiveness is one of the communicative strategies ( Fetzer & Lauerbach, 2007 ).

Participants share a common goal and cooperate to achieve it by means of conversation. Cooperation is characterised either by means of a set of imperatives or by imposing constraints on what parties are expected to do in the interaction ( Walton & Krabbe, 1995 ; Matheson et al., 2000 ).

From a rhetorical point of view, it can be said that arguments are effective and thus good ( Johnson, 2000: 189 ). It is the use of signs for communicating effectively in political practical discourse ( Booth, 2004 ). They are not only interested in maintaining and getting on with others in mutually cooperative way and aiming at the truth ( Misak, 2000 ).

As far as it is pertinent to pragma-dialectics, rhetoric is the potential effectiveness of argumentative discourse in convincing or persuading an audience in actual argumentative practice.

2.2. Aspects of Strategic Maneuvering

According to the latest exposition (Eemeren, 2010), the analysis of strategic maneuvering divides the rhetorical dimension into three inseparable aspects: topic potential, audience demand and presentational device. Strategic maneuvering manifests itself in argumentative discourse in the choices that are made from the topical potential available at a certain stage in the discourse, in audience-directed framing of the argumentative moves, and in the purposive use of presentational devices. In actual argumentative practice these aspects usually work together (cf. Kauffeld, 2002 ; Tindale, 2004 ).

In the actual argumentative practice of a political interview, the politician will make an attempt at reaching the dialectical aims and the rhetorical aims by coordinating in his move the three inseparable (though analytically distinguishable) aspects of strategic maneuvering: topical choice, audience adaptation and presentational means ( van Eemeren, 2010: pp. 93-127 ).

Together the aspects are instrumental for the rhetorical functionality of argumentative discourse, which means that all three aspects contribute to the acceptance of a standpoint.

2.2.1. Topical Potential

The first condition every strategic maneuver should meet to be considered reasonable pertains to the topical choice ( van Eemeren & Houtlosser, 2009 ).

Van Eemeren and Houtlosser explain that in their attempt to remain dialectically reasonable and at the same time rhetorically effective, arguers make a topical selection that is most favorable to their position. That is, arguers will select materials from those available according to what they believe best advances their interests.

When entering into a discussion with the interviewee, a certain policy defended by pragmatic argumentation an interviewer takes to maneuver strategically in advancing his criticisms. He needs to decide which critical questions are advantageous for him to raise.

For example, argumentation by a politician to maintain and defend a standpoint is regarded as outcomes which may be unfavorable to an interviewer who is making an accusation ( Mohammed, 2009 ).

2.2.2. Audience Demand

Walton suggests that different models should be considered for conflict resolution. Derailments of strategic maneuvering are those arguments that would fail to persuade the audience (cited in Johnson, 2000: p. 243 ).

In a political discourse, politicians do not present their face to the interviewer only. In fact, they present their faces to a bigger audience―an entire listening or viewing public, or indeed an entire nation or the world at large. Ivir (1975: 206) states that a speaker adapts his language to achieve his goals (cited in Larson, 1984: p. 336 ). Larson adds that the audience plays a significant role and should be taken into account ( Larson, 1984: p. 336 ).

Generally, politicians’ responses are appealing to audience demand. Thus, Politicians use these strategies which are regarded as indirect. Indirect responses demonstrate that the interviewees are paying close attention to their own face needs. Obeng (1994, 1997) and Wilson (1990) point out that due to the cancellable nature of implicatures, politicians cannot be accused of any statement they make in a political interview if it is made indirectly. Obeng (1994: p. 42) defines verbal indirectness as a strategy used to communicate “difficulty”. Any potential face-threatening act can be seen to communicate difficulty. Indirectness is therefore a face-saving or face-maintenance strategy. It protects the interviewee’s face needs from both the interviewer and the listening audience.

2.2.3. Presentational Devices

Another variety of strategic maneuver of special interest to pragma-dialectics is what van Eemeren and Houtlosser have called a “presentational device”, “the phrasing of moves in light of their discursive and stylistic effectiveness” ( van Eemeren & Houtlosser, 2001: p. 152 ; see also van Eemeren & Houtlosser, 2000, 2005 ). A presentational device an arguer exploits is to present an argumentation in one way rather than another so as to gain rhetorical advantage.

Eemeren (2010: 225) elaborated that in making presentational choices that manifest themselves in the discourse in a specific way, the Gricean Maxims ( Grice, 1989 ) are exploited in a specific way, often in combination with each other, to achieve certain communicative and interactional effects that serve a strategic function.

Anscombre and Ducrot (1983) identifies that, as Anscombre (1994: 30) puts it, guiding the discourse into a certain direction is something that can be achieved not only by “formal” presentational means, but also by “informal” presentational means, whose effect depends on the content, or by a combination of both types of presentational means (cited in Eemeren, 2010).

Obvious examples of formal devices are repetition, subordination, and paratactic, and hypotactic constructions (Eemeren, 2010); of informal devices are the tropes, the various kinds of metaphors, rhetorical questions, etc. Based on their pragmatic significance which can help achieve the aims of the present study done, only informal devices will be tackled.

Making use of presentational choices as manifestation of strategic maneuvering refers to utilizing the pragmatic strategies as a variation to steer the discourse toward the achievement of certain communicative and interactional effects (Eemeren, 2010: 119).

An argumentation, for instance, that is made in a political interview may be explicitly presented, but its communicative function is implicit. In other words, Implicit presentations are indirect if the communicative function or the propositional content of the speech act conveying the move is only a secondary function or content of the speech act that is literally performed whereas the primary function or content of the speech act is a different one.

Finally, it is worth emphasizing that combining rhetorical insight with dialectical insight is not unproblematic ( van Eemeren, 2001 ). However, pursuing effectiveness at the expense of dialectics can’t be understood properly only if it is viewed pragmatically.

3. The Models Related

This section is intended to develop the pragmatic model which will be adopted for the analysis of the data of the study. Different models have been developed for analyzing political discourse, however. These models serve the purposes of their approaches. Thus, the models will be reviewed and utilized to serve the purposes of this study.

3.1. Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson’s Model (1974)

Schegloff and Sacks (1973) offer a characterization that adjacency pairs are sequences of two utterances that are produced by different speakers and ordered as a first part and a second part so that a particular first part requires a particular second, e.g. offers require acceptance or rejections, greeting requires greeting, and so on (cited in Levin- son, 1983: pp. 303-304 ; Coulthard, 1977: p. 70 ; Cook, 1989: pp. 53-54 ; Yule, 1996: pp. 76-77 ; cf. Goffman, 1976 ).

According to Sacks et al. (1974: 696) , APs (henceforth) are parts of a conversation which consists of at least two turns. APs are produced successively by different speakers; they are ordered in the sense that the first must belong to the class of first pair parts while the second to the class of second pair parts; and they are related, not any second pair can follow any first pair part, but only an appropriate one. Sacks et al. (1974) also add that the types of the first pair part may be one of these types: greeting, question, challenge, offer, request, complaint, invitation, announcement, criticism, accusation and blame. They mention that the second pair may be reciprocal such as greeting-greeting or non-reciprocal such as questioning-answer.

Accordingly, what will be adopted from this model is the pragmatic strategies used at the first parts of the adjacency pairs represented by speech acts, viz. (question, request, accusation, and blame). These strategies adopted are liable to modification (which includes making some change to an already existing strategy or adding some possible one) and this is to be done in accordance with the data of the present study.

3.2. Jucker’s Model (1986)

According to Jucker’s (1986: p. 47) flow-chart, a political interview has a structure. Its structure consists of opening, body, and closing. The opening and closing phases of interview are routine and obvious practices: announcing the topic of discussion, introducing the guests, and thanking them at the conclusion for taking part. They constitute the boundaries of the interaction. They are etiquette practiced at the beginning and the end of interviews.

3.2.1. Opening

The interviewer introduces the topic of the interview and gives introduction about the interviewee. Openings are the utterances that precede the first question. They are absent from the adjacency pairs of ordinary conversation ( Schegloff, 1986: p. 123 ). Interview openings have three functions, each within a separate segment. Those functions are: headline, background, and lead-in. (cf. Clayman & Heritage, 2002 ).

3.2.2. Body

Beside the opening and closing, the most significant feature of the interview is that it appears as a series of questions and answers. This phase begins by the initiating move that is followed by the interviewee’s first answer. There is a social norm that participants have to restrict themselves to the actions of questioning and answering.

The interviewer asks the questions, and the interviewee supplies answers. These roles do not usually reverse ( Yoell, 2003: p. 2 ). However, the question and answer format is not a straightforward process in all types of interviews. For example, an answer may be implied in the politician’s response but not explicitly stated, or the answer is only in part, or the interviewer interrupts the interviewee that it is not possible to say whether or not an answer has been given ( Bull, 1994: p. 126 ).

This phase begins by initiating a move that is followed by the interviewee’s first answer. Interviewees normally produce turns at talk as responses to interviewer questions. Interviewers have the power to evaluate the interviewees’ answers whether they are supporting, i.e., answering the question, or not. When the answer is supporting, the interviewer has to decide whether the topic is exhausted or not. If the topic is not exhausted s/he will extend it (topic extension). If it is exhausted, s/he will introduce a new topic within the sphere of the overall topic of the interview (topical shift). When the answer is non-supporting, the interviewer produces a “reformulation”, or a challenge.

3.2.3. Closing

The interviewer ends the interview by addressing the interviewee by name and thanking him. The interviewer’s response is optional according to the flow chart.

On the basis of these points, what will be adopted from this model by this study is the terminology only, viz. the initiating stage, the response stage which is substituted for answer stage as that when politicians are not answering the question, they attempt to act responsively while not providing the information requested ( Fetzer, 2007: p. 179 ) and thus answers and non-answers are included within the response tactics ( Fetzer, 2007: p. 180 ), and finally the evaluation stage will follow the above model in that if the answer is supporting, the interviewer will resort to either topic shift or topic extension and if the answer is not supporting, the interviewer will resort to either reformulation or challenge. The eclectic model will adopt the number of stages, viz. three: initiating stage, response stage, and evaluation stage.

3.3. The Eclectic Model

The model which is intended to be developed by this study is based on what has been adopted through surveying the aforementioned models, alongside with the observations made by the researcher himself. The model of this study can be illustrated as follows:

3.3.1. Pragmatic Structure

With comparative reference to a conversational process, the eclectic model involves three stages: the initiating stage (IS), the response stage (RS), and the evaluation stage (ES). These three stages are built upon certain pragmatic components composing the pragmatic structure of strategic maneuvering. The process can be illustrated as follows:

The initiating stage triggers the topic potential of strategic maneuvering through the speech acts used. It is realized by various speech act strategies, viz. question, request, accusation, blame, etc.

The response stage comprises three pragmatic components, viz. hedges of the cooperative principle, conversational implicature and politeness principle. These pragmatic elements occupy two different complementary parts (sub-stages) that can be illustrated as follows. The first sub-stage is composed of two pragmatic elements. The first pragmatic constituent is hedges of the cooperative principle which is realized by hedges of the four maxims, the second is conversational implicature generated by violating the Gricean maxims of quality, quantity, relation and manner and is realized by different kinds of implicatures, viz. generalized conversational implicature, scalar implicature, particularized conversational implicature, and finally conventional implicature, and the third is the politeness principle which is recognized by observing the politeness strategies of Brown and Levinson. The second sub-stage is composed of the conversational implicature which is produced by violating the Gricean maxims mentioned above. The violated maxims are presented in the form of pragma-rhetorical tropes.

Finally, the evaluation stage comprises only one pragmatic element that is speech acts. These speech acts are used to effectuate topic shift, or topic extension, or reformulation, or challenge strategies to release the evaluation that concludes the whole process of strategically maneuvering situation.

In conclusion, the strategic maneuvering process actualized by the eclectic model developed by this study reveals that the pragmatic structure of strategic maneuvering incorporates four components, viz. speech act, hedges of cooperative principle, conversational implicature, and politeness principle over three stages.

3.3.2. Pragmatic Strategies

The three stages mentioned above have their own pragmatic strategies which are used to realize each of the aforementioned pragmatic components involved in the process of strategic maneuvering, as such each will be briefly discussed.

1) Initiating Stage

Generally, this stage comprises one pragmatic element (viz. speech act) distributed over the sub-stage topic potential. This sub-stage is triggered by one of the following speech acts: question, request, accusation, and blame.

1.1) Speech Act Strategies

It can be stated that speech acts play an essential role so as to pragmatically meet the interviewer goals. The interviewer’s goal is to tackle the topics that are adapted to audience demands. In order to get their strategic maneuvering goals accomplished, interviewers might employ the strategy of issuing one of the following speech acts:

1.1.1) Speech Act of Question

In Searle’s (1969: p. 66) terms, this SA is a subtype of directives. It is an attempt by S to get H to answer, i.e., to perform a SA.

Questions primarily have the illocutionary force of inquiries. Yet, they are often used as directives conveying requests, offers, invitations, and advice. ( Quirk et al., 1985: p. 806 ) The central topics of inquiry include implicature, presupposition, speech acts, and inference (Huang, 2007: p. 6). Put in this way, questions can be shaped to prefer particular responses ( Clayman & Heritage, 2002: p. 209 ).

1.1.2) Speech Act of Request

This is another speech act that is included within Searle’s (1969: p. 68) directives. There is a preference for agreement in political discourse. Thus, on making a request interviewers expect that others will fulfill the request; if this is not done, i.e. in refusing, for example, to perform the request, politicians will hurt the other’s positive face by failing to show consideration for his/her wants, and this drives participants to get into ineffec- tive argumentation ( Searle’s, 1969: p. 64 ). Figure 1 shows how the pragmatic structure of strategic maneuvering

![]()

Figure 1. A pragmatic structure of strategic maneuvering.

is designed.

1.1.3) Speech Act of Accusation

Accusations are that kind of acts that attack the person’s face. Accusing someone of something amounts to performing an assertive illocutionary act implying that the speaker commits himself to the truth, or more generally, to the acceptability of the proposition expressed and is supposed to have good grounds for putting it forward ( Searle, 1969 ). Accusations are made to serve a communicative purpose of bringing about illocutionary effects and an interactional purpose of realizing perlocutionary effects ( van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1984 ).

1.1.4) Speech Act of Blame

The speech act of blame can be defined as “the act of disapproving or condemning something bad” ( Searle & Vanderveken, 1985: p. 191 ). They ( Searle & Vanderveken, 1985: p. 182-183 ) label blame under assertive.

2) Response Stage

The second stage of the process of strategic maneuvering involves two elements: the audience demand which encompasses hedges of cooperative principles, conversational implicature, and politeness principle, and the presentational devices which contains the conversational implicature embodied in the pragma-rhetorical tropes.

2.1) Audience Demand

This sub-stage can be accomplished by resorting to the following pragmatic strategies: hedges of cooperative principles, conversational implicature, and politeness principle.

2.1.1) Cooperative Principle

According to Leech (1983) , the cooperative principle opens the channel of communication and the politeness principle keeps it opened. Fetzer and Weizman confirm these hypotheses and point out that political discourse― requires an investigation of language use in context and thus the accommodation of pragmatic principles. ( Fetzer & Weizman, 2006: p. 148 ) Politicians in a conversation frequently say less than they actually mean, which is, of course, true in case of politicians and their language. This distinction between literal and implied meaning is the basis of the Cooperative Principle (CP), which was defined by H. P. Grice (1989) . Within the framework of the CP, Grice suggested four maxims that―should ensure that the right amount of information is supplied in a conversational exchange. At the same time, H. P. Grice is conscious of the fact that discourse participants do not always fully cooperate in the flow of interaction and fail to observe the maxim (Kozubikova Sandova, 2010: p. 89).

2.1.1.1) Hedges of the Cooperative Principle

Austin’s (1962) and Searle’s (1969) work on the theory of speech acts and Grice’s conversational maxims are defined within the framework of the Cooperative Principle (1989). Politicians frequently say much less than they actually mean and in this way they are indirect. This phenomenon is connected with non-observance of the maxims of the Cooperative Principle defined by Grice (1989) .

2.1.1.2) Conversational Impilcature

Implicature is something that left implicit in the actual language use. Yule (2000: p. 35) states that speakers use implicature to convey additional meaning more than that stated by the words themselves. This means that for speakers to create more communicative effects, they tend to violate the cooperation maxims in order to decode their messages and hearers to recognize those meanings via inferences to adhere to the maxims. Yule (2000: p. 44) also stresses that implicatures are, on the one hand, deniable because the intended meaning with implicatures is part of what is communicated and not of what is said, therefore speakers can deny since they are not actually say it and on the other hand speakers are considered cooperative and thus maintain communication ( Yule, 2000 ). Yule (2000) lists three kinds of implicatures; they are generalized conversational implicatures with a sub branch called scalar implicature, particularized conversational implicatures, and conventional implicatures.

The conversational implicatures is produced by violating the Gricean maxims of quality, quantity, relation and manner. The violated maxims are presented in the form of the clarification.

2.1.1.2.1) Generalized Conversational Implicature

In this kind of implicatures, no special background knowledge of the context of utterance is required for their interpretation. In other words, when no special knowledge is required in the context to catch the additional conveyed meaning, it is called GCI (henceforth). A common example of this kind of implicature in English involves the use of the indefinite articles (a\an) in any phrase.

2.1.1.2.1.1) Scalar Implicature

Yule (2000: pp. 40-41) states that certain information can be communicated by choosing a word which expresses one value from a scale of values. This is most obvious in terms of expressing quantity, as in the use of one of the following listed terms from the highest to the lowest values (all, most, many, some, few) and (always, often, sometimes).

The effectiveness lies in that when any form in the scale is used the negative of all forms higher on the scale is implicated. That is when producing an utterance; a politician selects from the scale a word which is the most informative and truthful (Quantity and Quality).

2.1.1.2.2) Particularized Conversational Implicature

Unlike the aforementioned types, these implicatures can only be worked out with knowledge of context, i.e. they are highly context dependent. In order to preserve the assumption of cooperation in these implicatures to be relevant and effective, the meaning has to be inferred on the basis of the knowledge of the linguistic context that surrounds the utterances and on some background knowledge. The discourse of political interviews is a form of language that is produce in a political context, so the identification of particularized conversational implicature needs the knowledge of that context and knowledge of some background regarding the politics of USA.

2.1.1.2.3) Conventional Implicatures

Conventional implicatures are different from all other mentioned kinds. They are different in that they don’t rely on the maxims of the cooperative principle, they don’t have to occur in conversation and they do not depend on special context for their interpretation. Rather, they are associated with specific words resulting in additional conveyed meaning.

2.1.2) Politeness Principle

Brown & Levinson adopt the notion of face as a corner stone to their theory of politeness (see 2.4.3). They define face as “the public self-image that every member wants to claim for himself” ( Brown & Levinson, 1978: p. 66 ). Their strategies can be exploited by interviewees to maintain cooperation as part of their process of strategic maneuvering.

2.2) Presentational Devices

Presentational devices are utilized intentionally by interviewees in order to achieve certain aims.

Many rhetoricians, like McQuarrie and Mick (1996) , maintain that any proposition can be expressed in a variety of ways. One of these ways is the use of rhetorical figures of speech.

・ Among presentational devices, the figures of speech have often been identified in the rhetorical tradition as vehicles for particular lines of argument or for pragmatic adjustments between arguer and audience ( Fahnestock, 1999 ).

2.2.1) Pragma-Rhetorical Tropes

Of presentational devices, pragma-rhetorical tropes are pragmatic devices adopted by interviewee to persuade the audience of the interviewees’ responses. To do so, interviewees exploit those involving clarification: metaphor, simile, irony, and those involving emphasis: rhetorical question, understatement, overstatement ( Abu Krooze, 2012 ).

2.2.1.1) Metaphor

According to Carver and Pikalo (2008: p. 221) , a metaphor is to use an unusual term to describe a usual term, for example, “axis of evil” and thus “a word or a phrase establishes a comparison between one idea and another”. Unlike simile, the comparison is not made explicit by using “like” or “as” ( see Larson, (1984: p. 493) ; McGlone (2007) ; Sperber & Wilson (2008) ; Rozina & Karapetjana (2009) ; Mey (2009) ).

2.2.1.2) Simile

Cruse states that simile represents a comparison between two things of unlike nature that yet have something in common ( Cruse, 2006: p. 165 ). Larson affirms that these two things are compared by using explicit markers: like or as ( Larson, 1984: p. 493 ) (see also Kuypers, 2009: p. 97).

Despite the use of explicit markers, comparisons might be used effectively to leave the desired impact on the listeners of interviewees convincing them of their stands and certain facts.

2.2.1.3) Irony

The term irony as indicated by Roy (1981: p. 407) is a strategy that is sometimes used by the speaker to say totally the opposite of what he means (cited in Larson, 1984: p. 486 ). It is intended to criticise or to praise in an indirect, off record way ( Albaajuez, 1994: p. 10 ). In their attempt to define irony, Brown and Levinson consider irony as conveying criticism (1987: 262-3).

Shelley (2001: p. 776) is commonly used either as verbal irony or as situational irony. Only verbal irony will be tackled due to its importance to the advancement of the ideas of the present study.

2.2.1.4) Rhetorical Question

Unlike genuine questions, rhetorical questions are meant to be heard as questions and understood as statements. Rhetorical question is generally a question that neither seeks information nor elicit an answer ( Larson, 1984: p. 470 ). It is regarded as effective pragma-rhetorical trope that interviewees might utilize to persuade their audience of their beliefs and opinions. Rhetorical questions are argumentative strategies in which the speaker is not expecting to be answered. The purpose is to bring a problem to people’s minds and make them think of it ( Larson, 1984: pp. 474-475 ).

2.2.1.5) Overstatement

Hyperbole is a form of extremity, an exaggeration that either magnifies or minimizes some real state of affairs. It says more than what the speaker wants the listener to understand ( Beekman & Callow, 1974: p. 118 ). Sert asserts that it is the most common trope ( Sert, 2008: p. 3 ). Thus, it might be adopted by interviewees so as to magnify the bad actions of others and accordingly their position can be evaluated positively by the audience.

2.2.1.6) Understatement

The last pragma-rhetorical trope that is tackled by the present study is understatement. It represents a deviation from conventional communication and thus flouts the maxim(s) of cooperative conversational interaction ( Levinson, 1983: p. 110 ). According to Ruiz (2006: 2), an understatement is a statement which is because conspicuously less informative than some other statements can express the meaning of the more informative statement (cited in Hasan, 2012). Harris (2008: p. 9) assures that understatement purposely shows an idea as less important than it actually is.

3) Evaluation Stage

Interviewers have the power to evaluate the interviewees’ answers whether they are supporting, i.e., answering the question, or hedging. For instance, when the answer is non-supporting, the interviewer produces speech acts denote “reformulation”, or challenge.

For more clarification, the above discussed model (which will be adopted for the analysis of the data selected interviews later on) is systematically introduced in Figure 2, where each arrow (→) is to be read as “by means of”. Thus, the initiating stage is initiated by means of speech acts, and this leads to the Response stage and this, in turn, leads to the evaluation stage which can be either supportive or non supportive.

4. Data Analysis

This section deals with the practical side in this thesis, namely: data collection, description and analysis. However, it is worth mentioning the methodology of the analysis. Then, there will be some selected examples from the data to be analyzed.

4.1. Methods of Analysis

The developed model presented in Section Three will be used for analyzing strategic maneuvering in the selected political interviews under study.

The data collected for analysis are represented by (20) strategic maneuvering situations chosen from the two interviews as a whole. The interviews are chronologically ordered. The mathematical statistical tool that will be used for calculating the results of the analysis is the percentage equation.

The symbols that will be used through the analysis are presented in the below:

Inter.1 = Russert-Cheney interview 2002

Inter.2 = Lehrer-Obama Feb. 28th interview 2009

4.1.1. Selected Examples for Pragmatic Analysis

Due to the fact that the situations representing the data are too many, and analyzing all of them will occupy a large space in this work; only some illustrative examples will be presented viz. two examples from each interview. The choice of the situations is based on the conviction of the researcher that these are the most apparent, appealing and illustrative examples.

Inter.1

Situation (2): Mr. Russert: When we last spoke some eight months ago, you said it was not a matter of if, but when, the terrorists would strike again. Are you surprised they have not struck again within the past year?

Vice Pres. Cheney: I can’t say that I’m surprised, Tim. There’s sort of two ways to look at it. One is that there have oftentimes been long periods between major attacks. You know, World Trade Center in ‘93, Cole bombing in 2000, before that in ‘98 East Africa embassies, 2001, the New York and Washington attacks. On the other hand, we’ve also done a lot to improve our defenses. And we’ve been on the offensive with respect to the al-

![]()

Figure 2. An eclectic model for the pragmatic analysis of strategic maneuvering.

Qaeda organization. We’ve wrapped up a lot of them. We have a lot of them detained. We’ve totally disrupted their operations in Afghanistan, took down the Taliban. We’ve made it much more difficult I think for them to operate. Now, did they have a major attack planned in that intervening period? I don’t know. I suspect they probably did and I suspect we probably deterred some attacks. But does that mean the problem’s solved? Obviously not.

Mr. Russert: Leading up this September 11, 2002, are we hearing an increase in chatter? Are intelligence folks picking up conversations amongst the al-Qaeda cells around the world? (Inter.1: 2-3)

In this example, the Initiating Stage (Henceforth IS) consists of one pragmatic component, viz. speech act. The Topic Potential (Henceforth TP) as the only sub-stage of the IS contains the speech act element realized by releasing a question (Are you surprised they have not struck again within the past year?) that has the illocutionary force of accusation where the interviewer triggers strategic maneuvering through initiating the topic that appeals to audience. The topic, Russert triggered, is about terrorists impendent attacks that Cheney expected to happen. It is implied that Cheney was inconsistent.

The immediate Response Stage (Henceforth RS) is composed of three pragmatic components distributed over two sub-stages: the audience demand (Henceforth AD) and the presentational devices (Henceforth PDs). The first sub-stage represented by the AD consists of three pragmatic components: hedging the cooperative maxims, conversational implicatures and politeness principle. Hedging the Cooperative Principle is represented in the above situation by (I can’t say that) where the interviewee equivocates because a direct and explicit reply is impossible. It is also symbolized by the utilization of other hedges of the quality maxim like: I think, they probably, I suspect, we probably which all convey that the interviewee evades saying the truth. The truth resolves around Taliban operations, though that’s not to be taken for sure, have been taken down and it has been made difficult

for them to operate (see the example itself). Cheney also hedges the quantity maxim by lessening what is needed through employing (you know) where he equivocates to support his stand on the basis that the hearer knows the long periods between the major attacks (see the example for more information). He adds using the adverb (obviously) to suspect that some attacks still do not deterred yet and that the problem isn’t solved in spite of America defenses improvement. Next, to fulfill the same effect employed by hedging above and to leave things unsaid and not explicitly expressed, Cheney in the AD sub-stage uses the Conversational Implicatures represented by (oftentimes, some) as scalar implicatures and (but) as a conventional implicature. Plus, to serve his interests in mitigating the interviewer’s proposition and the hearer’s reactions towards him, the politeness principle is utilized by Cheney through giving a free rein to positive politeness strategies (Tim) (strategy 4), (we) (strategy 12), (you know) (strategy 7), negative politeness strategies (you know, I think, I can’t say, I suspect, they probably, we probably) (strategy 2), and off record strategies (sort of) (strategy 4), (totally disrupted) (strategy 5), (did they have a major attack planned … does that mean…) (strategy 10). These politeness strategies are brought into play to raise the idea that the American administration has done a lot to improve their defenses to prepare the ground for a safe American Nation against the terrorists imminent attacks. The second sub-stage is represented by the PDs which comprises the conversational implicatures brought forth by the use of the rhetorical tropes of overstatement and two rhetorical questions. The interviewee develops accentuated statement (we’ve totally disrupted their operations) as a way of generating an implicature by saying more than necessary (violating the Quantity Maxim), i.e., exaggerating or choosing a point on a scale which is higher than is warranted by the actual state of affairs to augment the positive side of their operations against al-Qaeda. Additionally, the two rhetorical questions (did they have a major attack planned…? does that mean…?) are used by Cheney to isolate himself from responsibility through violating the quality maxim and generating the conversational implicature which implicates that he is not sure and thus they have to continue their operations against al-Qaeda. Though these conversational implicatures violate the quantity and the quality maxims, the use of the presentational devices is to strengthen the purposes employed by the strategies at the audience demand sub-stage. It is worth mentioning that the answers supplied above in the example i.e. I don’t know and obviously after the two rhetorical questions by the interviewee himself are intended to reinforce the implication of the rhetorical questions. Such responses are not meant to answer the rhetorical questions, but to emphasize their implicit message as seen by the interviewee (Ilie, 1996: 104).

Finally, at the Evaluation Stage (Henceforth ES), the interviewer considers the interviewee’s answer as supportive. The positive pragmatic component is realized by issuing the speech act of question (Are intelligence folks picking up conversations amongst the al-Qaeda cells around the world?) which is regarded as an extension of the topic potential. The interviewer wants the interviewee to elaborate on the status of al-Qaeda organization around the world. Topic extensions are, as heritage (1985: 105) states, means used by the interviewer to prompt the interviewee to elaborate and reconfirm the prior inferences or statements (cited in Jucker, 1986: p. 128 ).

Situation (12): Mr. Russert: If Saddam did let the inspectors in and they did have unfettered access, could you have disarmament without a regime change?

Vice Pres. Cheney: Boy, that’s a tough one. I don’t know. We’d have to see. I mean, that gets to be speculative, in terms of what kind of inspection regime and so forth.

Mr. Russert: But what’s your goal? Disarmament or regime change?

Vice Pres. Cheney: The president’s made it clear that the goal of the United States is regime change. He said that on many occasions. With respect to the United Nations, clearly the U.N. has a vested interest in coming to grips with the fact of Saddam Hussein’s refusal to comply with all those resolutions. He pledged, you know, to give up all his chemical and his biological and his nuclear weapons and his ballistic missile capabilities beyond a certain range. And the danger here is that the United Nations and the Security Council will become to look like a toothless tiger; that they pass resolutions, addressing a major international problem, but then there’s never any action. There’s never any follow-through. There’s nobody providing any leadership to move forward.

Mr. Russert: So you don’t think you can get disarmament without a regime change?

Vice Pres. Cheney: I didn’t say that. I said the president’s objective for the United States is still regime change. We have a separate set of concerns and priorities with the U.N. And given the international community’s involvement with respect to the United Nations over the years in addressing this issue, we think that’s one of the places he needs to go to address this issue. We’re trying very hard not to be unilateralist. We’re working to build support with the American people, with the Congress, as many have suggested we should. And we’re also, as many have suggested we should, going to the United Nations, and the president will address this issue on Thursday of this week. Now, that’s all-doesn’t mean that we’re prepared to ignore the realities. I spoke about inspections as I did. And I don’t want to undercut the serious efforts that were made by a lot of good people. I’ve known and worked with some of the inspectors. The fact of the matter is, as long as he’s not willing to cooperate, as long as he’s doing everything he can to hide, what we’ve seen in the past is that in the end, the inspectors were not able to uncover everything. And we know he was able to hide materials, programs and keep it secret, even while the inspectors were in the country.

Mr. Russert: The foreign minister of Turkey said, “Any change in Iraq’s government system should be carried out by that country’s people.” Dick Armey, Republican, said that, we as a nation should not be doing pre- emptive strikes. International law-where is our right to remove or topple another country’s government? (Inter.1: 27-28)

In the above lengthy example, the interviewer proposes an accusation speech act (If Saddam did let the inspectors in and they did have unfettered access, could you have disarmament without a regime change?) to ignite the TP, i.e. it is possible to make Saddam let the inspectors in so that they have unfettered access and thus the United Nations can disarmament without indulging the American tropes in a regime change war which the USA government seems resolved on as the interviewer implies.

The AD, as the only sub-stage of the response stage in this situation, embraces two pretence strategies. First, the interviewee maneuvers using hedges of the quality maxim (I don’t know), of the quantity maxim (so forth) and of the manner maxim (I mean). They all have been used to equivocate answering the question indicating that they have to be suspicious about inspecting the regime true powers. Then, he makes the use of (have to) as a scalar conversational implicature. Besides hedging the cooperative maxims, the interviewee draws upon a positive politeness strategy (we) (strategy 12) to tackle strategically the incongruity of being uncooperative.

In the ES, the interviewer challenges this non-supportive response by recourse to stipulating the following implicit speech act (But what’s your goal? Disarmament or regime change?) to accuse the interviewee of not admitting that it is a regime change. Challenges are considered, as Heritage (1985: 108) explains, as means to test and probe the interviewee’s actions, attitudes and intentions. Heritage adds that they involve formalizing some presuppositions (the true intent of the Americans in this situation), as the interviewer proposes, implied in prior talks (cited in Jucker, 1986: p. 131 ).

The interviewee, at the second RS, puts onward, a hedge of quantity (you know) to limit the information conveyed by him and therefore prevent the breaking of the maxim of quantity i.e. all know that there is no need to explain that though Saddam Hussein promised to give up his chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons, he refused to comply with United Nations and his ballistic missile capabilities beyond a certain range. He also benefits from kinds of conversational implicatures: (a vested interest, a certain range, a major international problem) as generalized implicatures, (many, all) as scalar implicatures, (a toothless tiger) as a particularized implicature, (but) as a conventional implicature. They have all been advanced to attain the same result concerning hedging above. Next, by means of the politeness principle, the interviewee backs up his AD sub-stage. He utilizes a positive strategy (you know) (strategy 7), negative strategies (you know) (strategy 2), (there’s never any follow- through, there’s nobody providing any leadership to move forward) (strategy 3), (the goal of the United States) (strategy 8), and off record strategies (never, nobody) (strategy 4), (all) (strategy 5), (a toothless tiger) (strategy 9). The politeness strategies, in this situation, are all intended to express that the aim of the United States is to stop Saddam who refuses to obey the United Nations resolutions and therefore he represents a threat to the American Nation. At the PDs sub-stage, the interviewee makes use of the conversational implicatures effectuated by means of two rhetorical tropes, as indirect pragmatic strategies, to enhance the AD sub-stage. He makes use of simile (the United Nations … look like a toothless tiger) where the quality maxim is violated to stress the weakness of United Nations. He advances another trope viz. overstatement (there’s never any action and there’s nobody…) where the quantity maxim is violated to emphasize that there isn’t any action against Saddam regime and nobody is providing any leadership to stop him.

In the second ES, as the response is considered as non supportive and not enough, the interviewer unleashes the speech act of stating his viewpoint (So you don’t think you can get disarmament without a regime change?) as a reformulation of the previous question to leave the interviewee no room to evade the question. Reformulations are requests for the interviewee to be more explicit and clearer ( Jucker, 1986: p. 52 ).

The interviewee reformulates, at the third RS, his response resorting to different pragmatic strategies. First, he begins with hedging of the quality maxim (I didn’t say that, we think) to state that the United Nations is one of the places the USA president may need to go to address the issue about disarmament of Saddam without a regime change and then he utilizes a quantity maxim hedge (we know) to assert that one needs to suspect Saddam’s capability of hiding materials, programs and keep it secret even while the inspectors were in Iraq. Secondly, Cheney benefits from implicatures: a generalized implicature (a separate set of concerns and priorities) to denote that the UN and the international community are involved in addressing this issue, scalar implicatures (many, should, some) to implicate that many American people suggested we should go to the United nations, and a conventional implicature (even) to indicate that Saddam was able to hide weapons while the inspectors were in Iraq. Thirdly, the politeness principle is utilized through the use of positive strategies (I’ve known and worked with some of the inspectors) (strategy 7), (we’re… going to the United Nations, … the president will address, we’ll not ignore the realities) (strategy 10), (we) (strategy 12), the use of negative strategies (the serious efforts that were made by a lot of good people) (strategy 7), (I said the president’s objective for the United States is still regime change) (strategy 8) and the use of an off record politeness strategy (everything) (strategy 5). His use of the politeness strategies aims at cementing his ideas and supporting his pleas. Moreover, at the second PDs sub-stage, strategic maneuvering is strengthened through breaching the maxim of quantity. This is achieved by (everything) which is employed here as an overstatement strategy to reinforce interaction and to persuade and influence the hearer about the interviewee’s words and actions. Again, his maneuvering asserts his stand against Saddam military weapons.

The ES is terminated by a supportive evaluation whereby they both agree about what has been raised earlier. As such, the interviewer extends the topic through introducing the speech act of request realized via a statement (The foreign minister of Turkey said… we as a nation should not… topple another country’s government) so as to demand the interviewee to elaborate on what others have said.

Inter.2

Situation (15): Jim Lehrer: You have just been with 2000 U.S. Marines. Some have been in harm’s way, some are about to go in harm’s way, Iraq or Afghanistan, under orders from you as the commander in chief. Was this difficult for you this morning?

Barack Obama: Well, it wasn’t difficult because my main message was, number one, thank you. And the easiest thing for me to do is to express the extraordinary gratitude that I think all Americans feel for young men and women who are serving in our armed forces. And the second was to be very clear about our plans in Iraq, and that we are going to bring this war to an end. But I will tell you that the most sobering things that I do as president relate to the deployment of these young men and women. Signing letters of those who have fallen in battle, it is a constant reminder of how critical these decisions are and the importance of the Commander in Chief, Congress, all of us who are in positions of power to make sure that we have thought through these decisions free of politics and we are doing what’s necessary for the safety and security of the American people.

Jim Lehrer: These specific Marines that were in this hall that you were talking to, as you said, you said in your speech that some of these kids are going to be going to Afghanistan soon as part of the...

Barack Obama: That’s exactly right.

Jim Lehrer: And you also said in your speech that it’s―one of the lessons of Iraq is that there are clearly defined goals. What are the goals for Afghanistan right now? (Inter.6: 1-2)

The IS is triggered in the above situation through utilizing the speech act of accusation (You have just been with 2000 U.S. Marines. Some have been in harm’s way, some are about to go in harm’s way, Iraq or Afghanistan, under orders from you as the commander in chief. Was this difficult for you this morning?). The sense of accusation is traced on the basis that 2000 US Marines who are about to go in bad conditions are going, under orders of the interviewee as the commander in chief, to Iraq or Afghanistan soon in spite of his announcement that the US combat mission will end next year.

The RS is engendered by bringing in the AD which is realized by employing a hedge of quality (I think) to reduce the impact upon the audience concerning sending the marines to Afghanistan. Obama also utilizes a hedge of relation (well) to effectively adapt the AD sub-stage via sending a thank message to those young men and women who are serving in the American armed forces. Afterwards, the word (all) as a scalar implicature is used in order to implicate that he is supported by the entire American Nation. And, (but) as a conventional implicature is set forth by the interviewee to implicate that the deployment of those young men and women is the more critical decision ever made. The politeness principle is also employed via making use of positive strategies (we are going to bring…) (strategy 10), (we) (strategy 12), (because my main message…) (strategy 13); negative strategies (I think, well) (strategy 2), (have fallen in battle) (strategy 7), (It’s a constant reminder) (strategy 8); and off record strategies (wasn’t difficult) (strategy 4), (the easiest thing, extraordinary, all, the most sobering things) (strategy 5). These politeness strategies come forth to competently support the RS i.e. the American administration is doing what’s necessary for the safety and security of the American people. Finally, the PDs sub-stage used to strengthen the AD sub-stage is represented via the use of understatement and overstatement. The interviewee uses an understatement (wasn’t difficult) to minify the effect of the situation i.e. those Marines are going to Afghanistan and then he uses another one (the easiest thing) to demonstrate that the easiest thing for him is to express gratitude to those men and women. He in addition employs overstatements (extraordinary, all, the most sobering things) to make sure that the positive side of his stand is implemented (see the example itself).

The ES is challenged by the interviewer through setting free the speech act of question (… these kids are going to be going to Afghanistan soon…) with the illocutionary impact of criticism where he demonstrates that those marines are going to Afghanistan and thus they are going to be in bad conditions in spite of Obama’s announcement that the American Administration is going to bring this war to an end.

In the RS, the interviewee winds up the interviewer’s proposition by using a quantity hedge strategy (exactly) to indicate that he has just mentioned the reasons behind sending those marines to Afghanistan. A positive strategy (that’s exactly right) (strategy 5) is also employed to defend his stand that his move is to secure the USA.

This prompts a positive evaluation where the interviewer extends the topic through issuing the speech act of question (What are the goals for Afghanistan right now?).

Situation (16): Jim Lehrer: And you also said in your speech that it’s―one of the lessons of Iraq is that there are clearly defined goals. What are the goals for Afghanistan right now?

Barack Obama: Well, I don’t think that they’re clear enough, that’s part of the problem. We’ve seen a sense of drift in the mission in Afghanistan, and that’s why I’ve ordered a head-to-toe, soup-to-nuts review of our approach in Afghanistan. Now, I can articulate some very clear, minimal goals in Afghanistan, and that is that we make sure that it’s not a safe haven for al-Qaida, they are not able to launch attacks of the sort that happened on 9/11 against the American homeland or American interest. How we achieve that initial goal, what kinds of strategies and tactics we need to put in place, I don’t think that we’ve thought it through, and we haven’t used the entire arsenal of American power. We’ve been thinking very militarily, but we haven’t been as effective in thinking diplomatically, we haven’t been thinking effectively around the development side of the equation, you know, what are we doing to replace poppy crops for Afghans that allow them to support themselves. Obviously, we haven’t been thinking regionally, recognizing that Afghanistan is actually an Afghanistan/Pakistan problem, because right now the militants, the extremists who are attacking U.S. troops are often times coming over the border from Pakistan. So that’s why we’ve assigned an envoy, Richard Holbrooke, to work comprehensively in the region, and this review that we’re talking about should be completed by the middle of next month. I will then be reporting to the American people and Congress about how exactly we are going to be moving forward in Afghanistan.

Jim Lehrer: As you know, Mr. President, there’s a traditional language for these kinds of conflicts, and its victory, or its loss, you win a war or you lose a war. Is there a victory definition for Afghanistan now or is that part of your thinking at this moment? (Inter.6: 2-4)

In this example, the IS is triggered by the TP which is realized through performing the speech act of question (What are the goals for Afghanistan right now?).

In the following RS, the interviewee uses a hedge of quality (I don’t think) to indicate that the goals for Afghanistan are not clear and this leads Obama to order a completely assessment of the American administration ideas and actions in Afghanistan. He also utilizes hedges of quantity (you know, obviously, exactly) to indicate that they [the American administration] haven’t been thinking regionally i.e. the extremists who are attacking US troop are coming over the border from Pakistan and not from Afghanistan. And, Obama makes use of a hedge of relation (well) to show the reason behind sending those Marines to Afghanistan. Subsequently, he uses, for the purpose of discourse continuity, a generalized implicature (a sense of drift) to depict that the mission in Afghanistan is somehow drifted and thus the goals of American in Afghanistan are not clear. Moreover, the interviewee applies a scalar implicature (some) to implicate that they [American administration] can abide by new very clear minimal goals in Afghanistan i.e. to make sure that al-Qaeda extremists are not able to launch attacks against American homeland or American interest. Furthermore, he puts forth (a head-to-toe, soup-to-nuts) as particularized implicatures to delineate that there is a need to reconsider the American mission in Afghanistan. As well, he uses another particularized implicature (a safe haven) to indicate that the extremists are no longer able to attack the American Nation. In addition, he brings in a conventional implicature (but) to explicate that the American administration is going to behave diplomatically from now on. The other part of the AD sub-stage is represented by the politeness principle which is realized by the use of positive strategies (we) (strategy 12), (that’s why, because) (strategy 13), (they are not able) (strategy 11), (I will be reporting, we are going to be moving forward in Afghanistan); negative strategies (I don’t think, you know, obviously, exactly, well) (strategy 2), (should be completed) (strategy 7); and off record strategies (entire) (strategy 5), (a head-to-toe, soup-to-nuts, a safe haven) (strategy 9), (how we achieve that initial goal, what kinds of strategies… to put in place) (strategy 10). These politeness strategies are employed here to efficiently transfer his message i.e. they [the American administration] are going to reconsider their goals in Afghanistan and they are going to spark the diplomatic side. Finally, the same tools used earlier, as particularized implicatures, are also used as rhetorical tropes i.e. realized by series of metaphors (a head-to-toe, soup-to-nuts, a safe haven) in the next PDs sub-stage to effectively strengthen the same purpose aimed at the aforementioned AD sub-stage; two rhetorical questions (How we achieve that initial goal, what kinds of strategies… to put in place) with an effort to implicate that they [American administration] are thinking of using another kind of weapon realized through diplomatic maneuvers; and an overstatement (entire) to exaggerate the Americans ability of tackling the problem of the extremism in Afghanistan and to indicate that they are going to achieve progress in Afghanistan.

The ES is supportive i.e. the interviewer extends the topic by emancipating the speech act of question (… Is there a victory definition for Afghanistan now or is that part of your thinking at this moment?).

This situation is regarded as supportive since the interviewer ends it with the speech act of thanking (prime minister, thank you very much indeed. Thank you).

4.1.2. Findings and Discussions

After analyzing the selected situations in the data, the findings of the analysis are to be tested in order to meet the aims and to verify or reject the hypotheses of this study.

The findings reveal that strategic maneuvering is an interpersonal process which consists of three stages: the initiating stage, the response stage, and the evaluation stage. These stages are composed of certain pragmatic strategic components forming the pragmatic structure of strategic maneuvering.

In the first stage, the findings in situations 2, 12, 15, and 16 in the examples analyzed are compatible with the findings of the situations listed in Table 1, 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 17, 18, and 19. Together, they fulfill the first aim in this study (i.e. investigating the most common strategies used by the interviewer at the initiating stage). These findings also verify the first hypothesis (i.e. interviewers tend to use particular strategies more than other strategies).

As for stage two, situations 2, 12, 15, 16 as well as those in Table 1, are compatible with the finding. They fulfill the second aim as well as the second hypothesis.

Finally, in the third stage, situations 12, 15 as well as those in Table 1, agree with the finding. Together they achieve the third aim and verify its third hypothesis.

4.1.3. Mathematical Statistical Analysis of the Interviews

The aim of this sub-section is to verify, in a mathematical statistical method, the findings which accord with the aims and hypotheses of this study, as in the following formula (Cited in Wikipedia.org):

Thus, the occurrence of each strategy in the process of strategic maneuvering in the two political interviews, which are (20) in number, is stated in Table 2:

The following results in the interviews are demonstrated in Table 2:

1. In the intiating stage, question and accusation have the highest percentage (that is, question 45% and accusation 30% respectively). Accordingly, the second hypothesis in this study is verified.

2. In the response stage, hedging of the quality and quantity maxims, generalized and scalar implicatures, positive and negative politeness, and the two rhetorical tropes, viz. overstatement and understatement have the highest percentage (that is, 81% and 59%, 61% and 65.9%, 93% and 84%, and 50% and 34% respectively) among other strategies. Accordingly, this verifies the third hypothesis.

3. In the evaluation stage, the pragmatic strategy of challenge has the highest percentage (that is 36.36%) among the others. This verifies the fourth hypothesis of the study.

![]()

Table 1. Analysis of the remaining situations.

Key: IS = Initiating stage, TP = Topic potential, RS = Response stage, AD = Audience demand, CP = Cooperative principle, HCP = Hedges of the cooperative principle, CIs = Conversational implicatures, QL = Quality, Qn = Quantity, R = Relation, Mn = Manner, GI = Generalized implicature, SI = Scalar implicature, PI = Particularized implicature, CI = Conventional implicature, On R = On record, Off R = Off record, PP = Politeness principle, NN = Negative politeness, PD = Presentational device, ES = Evaluation stage, O = overstatement, U = understatement, M = metaphor, I = irony, CP = comparison, S = supportive, NS = Non supportive, TS = Topic shift, TE = Topic extension, Rf = Reformulation, CH = Challenge, Q = question, Rq = request, AC = accusation, B = blame, CR = criticism, SU = suggestion, ST = stating.

Given all the percentages of these three stages, one can say that the process of strategic maneuvering can only be conveyed through stages represented by the three stages of initiating, response and evaluation. Accordingly, this verifies the first and the fifth hypotheses.

5. Conclusion

On the basis of the findings of the analysis, the study has come up with the following conclusions:

![]()

Table 2. The three stages of strategic maneuvering calculated in percentages in the interviews.

Key: IS = Initiating stage, RS = Response stage, ES = Evaluation stage, HCP = hedges of the cooperative principle, CIs = conversational implicatures, Ql. = quality, Qn. = quantity, R. = relation, Mn. = manner, GI. = generalized implicature, SI. = scalar implicature, PI. = particularized implicature, CI. = conventional implicature, On R. = on record, Off R. = off record, pp = positive politeness, NP = negative politeness, Sm = simile, M = metaphor, O = overstatement, RQ = rhetorical question, U = understatement, I = irony, CP = comparison, Q = question, Req = request, AC = accusation, B = blame, CR = criticism, SU = suggestion, ST = stating.

The pragmatic structure of strategic maneuvering is made up of a speech act, hedges of the cooperative principle, conversational implicatures, and politeness.

The speech acts of question and accusation are the most pragmatic strategies of initiating the topic potential of strategic maneuvering in the selected interviews. This finding is evident in the percentages of their high use (that is, 45%, and 30% respectively) in the six interviews as a whole.

Hedges of the quality and the quantity maxims, generalized and scalar implicatures, and positive and negative politeness are the most pragmatic strategies by which the second aspect of strategic maneuvering is adapted. This is clearly shown by the high percentages of the employment of these strategies, (81% and 59%), (61% and 65.9%), and (93% and 84%) in that order.

By using overstatement and understatement, the third aspect of strategic maneuvering is accomplished and this is evident in the high percentage of the usage of these strategies (50% and 34%).

Challenge is the most common pragmatic strategy of evaluation in the evaluation stage in the six interviews with a ratio of 36.36%.

The interviewers’ non-supportive evaluation of the interviewees’ responses dominates and this is supported by the overall result of non-supportive evaluation that is, 53.96%.

Interviewees have made their discourse pragmatically effective by using the hedges of the cooperative principles just to convince the audience that they are observing what they are saying. They also evade responsibility of the issues that may put them in a negative characterization, mostly, by using the different kinds of implicatures where they indicate that they are indeed being responsive to a given question.

Keeping to the Politeness Principle is also very important. This is evident when revealing that in the majority of the situations this principle has been appealed to by the interviewees.

Hedging the cooperative maxims and the use of conversational implicatures do not mean that the interviewees have not been cooperative. Rather, they have been employed to be imposed by politicians upon the audience as truthful, informative, unambiguous and relevant so that their moves could be estimated as cooperative and effective.

The strategic maneuvering aspects: topic potential, audience demand and presentational devices accordingly play an indispensable role in creating persuasive and manipulative political discourse especially in the selected political interviews. Besides, strategic maneuvering aids a better understanding of the political interviews selected.

The eclectically developed model has been found to be useful and adequate for pragmatically analyzing strategic maneuvering in the selected interviews.

Web Sources

https://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/bush/cheneymeetthepress.htm

http://www.nbcnews.com/id/4179618/ns/meet_the_press/t/transcript-feb-th/

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/newsnight/4482015.stm

http://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/frostovertheworld/2006/11/2008525184756477907.html

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/politics_show/7877564.stm

http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/politics-jan-june09-obamainterview_02-27/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Percentage