The Right to Physical Activity in Italian Prisons: Critical Considerations on Official Data ()

1. Introduction

Speaking of prison means talking about the sense of punishment and, therefore, about human being. Penalty is the only sanction that affects the primary good of the person: freedom, which has to do with dignity. Conceptions of punishment are essentially divided into two strands: on the one hand, that of the sense of retribution, which remunerates the malum actionis with the malum passionis, and finds its explanation in an absolute sense in the relation crime/sanction, according to the Hegelian conception for which the penalty is the denial of the crime and therefore the reaffirmation of the State. On the other hand, the paradigm of the preventive sense, which instead bases its essence on the ultimate goal: the good of society; it arises in the ambit of the eighteenth-century utilitarianism of Beccaria, but finds its epistemological basis in the well-known “maxim” of Seneca, who in “De Ira” (I, 19) writes: “Nemo prudens punit quia peccatum est sed ne peccetur”. According to this paradigm, the malum actionis must be answered not with the malum passionis but with bonum actionis. So, according to the multifunctional concept of punishment, it is possible to distinguish various functions of the same:

1) General negative prevention (dissuading from committing crimes);

2) Positive general prevention (inducing not to commit crimes);

3) Negative special prevention (neutralizing the offender);

4) Positive special prevention (reeducating the offender).

The Italian Constitution embraces this last function, clearly saying in the art. 27 that: “the penalties must tend to the rehabilitation of the condemned” and thus reaffirming the centrality of human dignity, of the dignity of every person. The law reforming the Italian penitentiary system (L.354/1975) establishes on this line that “the penitentiary treatment must be in conformity with humanity and must ensure respect for the dignity of the person” (art. 1). This reform introduced a series of fundamental principles of extreme importance; among these, the introduction of the figure of the penitentiary educator. One of the pillars of the Law was that of penitentiary treatment, inspired by the principles of humanity and dignity of the person. This treatment, according to article 13, must be individualized, that is to respond to the particular needs of the personality and to the resilience of each subject. In this context, the paradigms of security and treatment have equal value and equal dignity: the performance of activities that recognize the rights of prisoners to training, work, religious practices, physical activity is assured by justice policies at an international level.

The research problem in this study concerns the analysis of the adherence between the international and national regulatory provisions that ensure timing and modalities for the management of physical activity in prison and the real activation of them in Italy: the sport in prison is actually guaranteed and carried out? Is it implemented as a rehabilitation activity or only as a mere self-managed and “onanistic” exercise? What distance is there between the signed memorandums and the projects actually in place? These and other questions will try to answer this article.

Before, it seems appropriate to introduce now some international codes that provide for and ensure the performance of physical and sports activities in prisons a fundamental right for the prisoners.

2. International Rules on Sport in Prison. A Comparative View

Many codes provide for the recognition of human rights in the prison trough physical and sport activities. In this section, we will deal with the main provisions at an international comparative level, with a particular reference to English, Romanian, French and Italian contexts.

Art. 27 of the “Prison Rules” (1964 No. 388), issued in England, refers to the “daily exercise” that must be insured to prisoners: “a prisoner […] shall be allowed to exercise in the open air for no less than one hour in all, each day, if weather permits”. The subsequent and more current Prison Rules (1999 No. 728) assume re-education of the prisoner as a priority; in fact, in various articles of the law, the need to maintain external contacts is established, as well as the need to follow the prisoner also in the post-release phase and after his return to society, implementing projects and activities for treatment purposes. And so:

Outside contacts

4. 1) Special attention shall be paid to the maintenance of such relationships between a prisoner and his family as are desirable in the best interests of both.

2) A prisoner shall be encouraged and assisted to establish and maintain such relations with persons and agencies outside prison as may, in the opinion of the governor, best promote the interests of his family and his own social rehabilitation.

After care

5. From the beginning of a prisoner’s sentence, consideration shall be given, in consultation with the appropriate after-care organisation, to the prisoner’s future and the assistance to be given him on and after his release.

Specifically, regarding the possibility of carrying out physical activity and spending time outdoors, the conditions for participation in such activities (age of prisoner, time of activity) are specified in detail:

Physical education

29. 1) If circumstances reasonably permit, a prisoner aged 21 years or over shall be given the opportunity to participate in physical education for at least one hour a week.

2) The following provisions shall apply to the extent circumstances reasonably permit to a prisoner who is under 21 years of age

a) provision shall be made for the physical education of such a prisoner within the normal working week, as well as evening and weekend physical recreation; the physical education activities will be such as foster personal responsibility and the prisoner’s interests and skills and encourage him to make good use of his leisure on release; and

b) arrangements shall be made for each such prisoner who is a convicted prisoner to participate in physical education for two hours a week on average.

3) In the case of a prisoner with a need for remedial physical activity, appropriate facilities will be provided.

4) The medical officer or a medical practitioner such as is mentioned in rule 20(3) shall decide upon the fitness of every prisoner for physical education and remedial physical activity and may excuse a prisoner from, or modify, any such education or activity on medical grounds.

Time in the open air

30. If the weather permits and subject to the need to maintain good order and discipline, a prisoner shall be given the opportunity to spend time in the open air at least once every day, for such a period as may be reasonable in the circumstances.

Even in Romania1, prisoners are given the right to practice sports, (…) in this particular case on a voluntary basis:

Practicing sports

Access to sports activities is guaranteed to all prisoners who are medically fit and wish to attend them.

Depending on existing possibilities, the penitentiary administration provides prisoners, in specially equipped spaces, with individual or group games or sports and recreational activities, in order to maintain their physical and mental condition, taking into account their health, skills, age and preferences.

Prisoners kept in open, semi-open and closed regime can attend sports activities performed outside of the prison.

At least one competition is organised in each prison every month, attended by prisoners.

At least one sports competition is organised in each prison every quarter, attended by prisoners, taking into consideration seasons and existing material basis.

Similarly, in France2, art. 27 of the Loipénitentiaire of 24 November 2009 stipulates that the detainee should be proposed activities aimed at reintegration, and in particular:

“Anyone sentenced is required to perform at least one of the activities proposed to him by the head of the establishment and the director of the prison service as soon as it is intended for the reintegration of the person concerned. (Activities are) adapted to his age, abilities, disability and personality” (my translation).

Furthermore, in the transalpine country, the type of sport activity offered varies according to the type of structure; in the scenario of the prison structures, two important categories can be found: the “maisonsd’arrêt” (literally the “short-stay prison”) and prisons. The distinction between these two types of structures is based on various criteria: the criminal “category” of individuals, the specific regime of detention and the level of security. The “maisonsd’arrêt” include people whose detention is a precautionary measure, people awaiting transfers or convictions, or prisoners whose residual sentence is less than 2 years.

A specific feature of these structures is the frequent “turnover” of prisoners and an often very high average occupancy. Sports activities play an essential role, both for their playful nature (such as football or body building), and their educational character: sport for health reasons and to learn the rules by preparing for freedom. In “MA”, only convicted individuals can benefit from exit permits, but there are few activities organized outside, as prisoners are often simply waiting to be transferred or about to be released. Instead, many events are organized by welcoming teams from outside (local clubs) or during sports championships.

Therefore, prisons are divided up into detention centres and maisoncentrales: the “detention centres” (CD) accommodate individuals convicted with sentences of a variable duration. Prisoners can leave their cell for most of the day. For this reason, this type of structure favours the development of sport activities as well as socio-cultural and training activities.

One of the objectives of this type of detention facility is to develop contacts with the external society, allowing, on the one hand, civil society actors to penetrate the prison environment more easily, through the organization of different events and, on the other hand, granting individuals with exit permits more frequent and longer-lasting external sporting opportunities, in order to facilitate their reintegration. In detention centres, the sports offer is certainly more interesting and diversified than in the other two types of detention facilities. This type of structure includes every form of participation in sporting events: from sports activities accessible to all, to specific events such as Téléthon or the Sports Festival; from competitions to exit permits for sporting reasons. The “maisonscentrales” (central prisons) welcome prisoners whose criminal profile is risky, convicted to very long sentences and whose prospects of reintegration are not immediate. The typical custodial regime of these structures focuses on reinforced security. The average age is generally higher than in the “MA”. Incentralprisons, prisoners have easier access to sports facilities, with much more free time outside the cell than the one expected in MA’s. Regular sporting events can be organized, although the participation of prisoners, or in local championships, as well as access to the structure by external teams, are very complex operations. Sports activities in this type of structure are often focused on individual activities (body building) or group activities (football) among prisoners; several regular events are organized, such as “friendly” competitions.

In Italy, as far as sport is concerned, the first article that reference is made to is article 15 of law 354/1975: “Treatment of the convict and of the prisoner is mainly carried out using education, work, religion, cultural, recreational and sports activities and promoting timely contacts with the outside world and relations with the family. […]. If they so request, the accused are allowed, to participate in educational, cultural and recreational activities. […]”. And therefore art. 27 states:

“Institutions should promote and organise cultural, sports and recreational activities as well as any other activity aimed at forming the personality of each prisoner and convict, also with a view to re-educational treatment. A Commission formed by the Prison Warden, educators and social assistants and prisoner and convict representatives deals with the organization of the activities as indicated above, also maintaining contacts with the outside world necessary for social reintegration”.

The legislator therefore foresees that the institutes will carry out all of the activities that may be useful for the development, evolution and growth of the personality of prisoners (see Chalat, 2012). First of all, the task of administration is not only to organize the activities, but also to promote their conception and realization, stimulating participation of the prisoners themselves in these operations. From a programmatic point of view, the legislator just outlines some of the preferential guidelines of the activities indicated herein, according to their beneficiaries: the context must be characterized by various initiatives favouring the possibility of differentiated expressions (see Young, 2019). Secondly, planning and implementation of the activities are expected to be organized by a commission that also includes prisoners.

A strong element of socialization, integration and overcoming of the difficulties that the prisoner faces in prison life can be easily found in these fields of participation. Finally, it is important to emphasise that execution of the activities mentioned above should not be conceived solely as a specific element within the prison institution (UNICEF, 2011). The objective of the legislator is, in fact, to conceive the action carried out within the prison structures according to contacts with the outside world, useful for the purpose of reintegration into society and, in any case, capable of breaking down the wall that separates the prison from the rest of society (see Cashin, Potter, & Butler, 2008).

Beyond their intrinsic value, the aforementioned activities constitute a cornerstone of the treatment process: in fact, participated collaboration in the organization and in the performance of the mentioned activities represents a positively evaluated element in order to grant rewards and prizes. Furthermore, art. 10 mentions the possibility of practicing physical activity in district prisons: “[…]. Time spent outdoors (…) is dedicated, if possible, to physical exercise”. This article defines the minimum content of the right to stay outdoors which must last a “minimum” of two hours per day. It is important to remember that time spent outdoors by the prisoner is never an act in itself but it clearly satisfies the desire to contain, in some way, the negative effects of imprisonment whose can almost always be seen on an individual level from a health and psychological point of view.

More recently, Article 59 of the Public Reg. Dec. 230/2000 states that:

“1) Cultural, recreational and sports activities are organised so as to favour the possibility of differentiated expressions. These activities should be organized to favour the participation of working and student prisoners and convicts. 2) The sport activity programmes focus, in particular, on youngsters; the collaboration of national and local boards in charge of organizing sports activities should be encouraged. […] 4) Through the collaboration of convicts and prisoners […], the Commission deals with the organisation of various activities according to the scheduled programmes […]. 6) In the organisation and execution of activities, Management can use the services of volunteers and individuals indicated in art. 17 of the law”.

Furthermore, art. 16 of this Regulation states that sports activities are practiced outdoors:

“1) Besides the objectives indicated in article 10 of the law (Law 354/75) outdoor spaces are used for treatment activities and, in particular, for sports, recreational and cultural activities according to the programmes prepared by Management. 2) Time spent outdoors (…), should be guaranteed (…), as an instrument to limit the negative effects of deprivation of personal freedom (….)”.

3. The Main Memorandums of Understanding in France and Italy for Sport in Prison

In addition to international regulations and national laws, the memorandums of understanding that regulate the use and the objectives of sport within prisons also deserve attention. These are documents confirming an agreement between the parties (often between public bodies, less frequently with the participation of private individuals), normally of a political rather than legal nature, binding the parties to undertake and observe the respective commitments contained therein.

We will consider in a comparative way the realities of France and Italy: in the first case, the memorandum of understanding between the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Sport; in the second case, the existing protocols between the Ministry of Justice and third sector associations. As far as France is concerned, the various protocols, dating back to 1986 but subsequently updated, reflect the willingness of numerous institutions to consider sporting practices as an instrument to fight social exclusion. “Doing sport” implies the involvement of an individual in the development of a personal project, and his “involvement” in dynamics and interpersonal relationships. Currently, about 17 sports associations have signed memorandums of understanding with the French Ministry of Justice aimed at the conciliation of social reintegration activities intended for prisoners.

In the context of a partnership between the Ministry of Justice and the Sports Movement since 2004, the sporting practices proposed are diversified and are decisive both for responding to the physical needs of prisoners and for applying educational approaches that are elaborated in conciliation with external youth support services, with territorial communities and with the associative sector.

In this sense, the French Ministry of Justice affirms its willingness to promote action aimed at facilitating the release of prisoners as well as an effective fight against recidivism, in accordance with the law of 22 June 1987. It considers physical and sporting activities intended for prisoners as an essential factor in achieving personal balance and facilitating their reintegration. The practice of physical and sporting activities, simultaneously representing a practice and an instrument of education, contributes towards safeguarding of the health and social reintegration of prisoners, be they juveniles or adults, helping them to structure themselves and reassert themselves as individuals (Esposito, 2012; Meek, 2014).

For all of this to be possible, especially to facilitate the recovery of those in difficulty, the Ministry of Justice attempts to establish relationships with entities able to support the activities that it plans to promote and that may help towards preparing a high-quality offer, enhanced by the diversification of practices and with reference to the world of associations3.

In Italy, there are many memoranda of understanding that the Ministry of Justice has stipulated with Third sector associations. The memorandum of understanding between the Department of Penitentiary Administration (DAP) and the Italian Association of Culture and Sport (AICS) dates back to December 1986 and is the oldest form of collaboration between the prison world and the promotional sports reality. Ever since then, the number of opportunities has multiplied; almost all Italian prisons have opened their gates to the sporting members of AICS, UISP, CSI and ACLI Sport. The most important protocols implemented between the Ministry of Justice and sports associations, presented here for the first time and based on official information provided by the DAP, are as follows4:

CONI (Italian National Olympic Committee)

A protocol elaborated in 2010. The text was revised in 2013 and renewed on 29 November 2017 with the new CONI presidency. It is a form of collaboration that plans sports and training courses through which CONI athletes involve prisoners in initiatives with a high educational value: sport-related values but undertaking a re-educational value in prison. It is important to underline the DAP’s commitment to undertake actions aimed at the redevelopment of environments and spaces for sports activities, as well as the creation of suitable and functional places for planned sporting activity.

The collaboration involves the implementation of an annual sports programme for prisoners, including both team and individual sporting activities, in activities with congenial characteristics for the objectives of re-education and training of the prisoners as well as the structures and equipment already available in the prison institutes, offering the possibility of contributing to the acquisition of sports equipment (individual and team equipment) as well as the supply of material and equipment needed in sports facilities.

UISP (Italian Union Sport for All)

The Protocol signed with the Penitentiary Administration Department for the first time in 1993 and renewed both in 2007 and 2012; expired in 2015 and renewed again on February 10th 2016.

The Protocol aims at improving the offer of opportunities to promote the development of the prisoner through the implementation of sports activities, in order to enhance physicality, to promote the acquisition of skills and contribute towards the reduction of tension induced by detention through the promotion of subjective and relational potential also with a view to future social reintegration.

The network model is chosen as the most suitable method for implementation of joint projects to improve educational and social assistance initiatives and to pursue shared objectives that involve the various institutional actors.

There are many points according to which the DAP and the UISP intend to carry out intervention of a sporting nature intended for prisoners; acquiring a sports culture founded on the values of continuity of practice, self-discipline and aggregation is a very important goal; the expansion of physical and sport activities also offers, wherever possible, the involvement of families; training activities, including professional activities, in the specific sector, in order to provide opportunities for social reintegration, compatibly with safety requirements; activities that promote communication between everyday prison life and the outside environment, promoting tournaments and sporting events, with the joint participation of the prisoners as well as external athletes. The experience and the routes adopted involve education towards legality through sport, the insertion of individuals on a detention and not detention level in educational circuits of sports clubs and UISP regional committees, also with the objective of promoting professional training, integration and work support initiatives.

AICS (Italian Association of Culture and Sports)

The Memorandum of Understanding between the Ministry of Justice-Juvenile Justice Department and the Italian Association of Culture and Sports (AICS), was signed in December 1986 and renewed on April 14, 2007 in Castellammare di Stabia. A long-standing collaboration has been active for several years, both in the external penal area and in the internal criminal area. The protocol states that the association undertakes to guarantee the activation of initiatives of a cultural/recreational nature and of a sporting nature. Furthermore, the reintegration of projects is envisaged through the benefits of law to foster continuous paths for transition to the free world.

CSI (Italian Sport Centre)

The Department of Juvenile Justice and Community and the Italian Sports Centre have started a profitable collaboration since 2005/2006; on 1st August 2007 the protocol between the Juvenile Justice Department and the Italian Sports Centre, a sports and social promotion body, was signed.

The Memorandum of Understanding with the Penitentiary Administration Department was signed on 11 June 2015. The protocol includes sports activities aimed at the acquisition of a sports culture based on the values of community life, self-discipline and aggregation. Furthermore, the organisation of sporting activities, possibly with the involvement of families and external agencies, aimed at social reintegration, is expected.

US ACLI (Italian Christian Workers Association)

A Memorandum of Understanding between the Penitentiary Administration Department and ACLI Sports Union has been in place since October 26, 2016. The construction of a solid relationship between institutes and the reference territory is envisaged, through the promotion of activities involving the joint participation of prisoners and athletes.

One of the key points of this protocol is the promotion of an intercultural, inter-ethnic, inter-religious coexistence of the prisoners. Beyond natural contextual differences, some fixed points can be attributed to the Justice Policies of both countries: formal attention to sport as a vehicle for social inclusion and work reintegration, formal attention to contacts with the outside world and to socialisation agencies, formal attention to the cathartic, inclusive and aggregative role of sport, formal attention to the re-socializing and personalizing function of sport participation, formal attention to sport as a limiting factor for recidivism.

4. Sports Activities and Projects in Italian Prisons

In order to respond to the research problem reported above, we now present data on sports activities in Italian prisons, to try to understand the level of adherence between international codes, memorandum of understandings and actual presence of physical activity in prison settings. The data provided by the Department of Penitentiary Administration of the Ministry of Justice, updated in 2017 and presented here to international readers for the first time5, show the picture of a rather heterogeneous sports treatment reality.

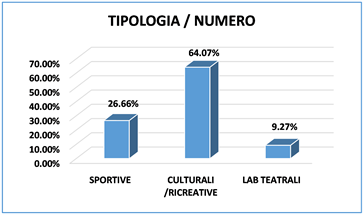

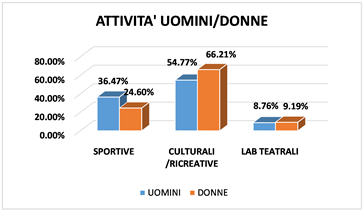

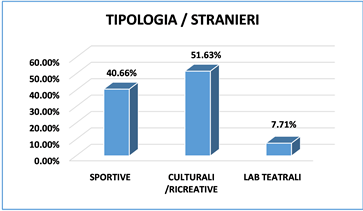

From Table 1, and related Graphs 1-3, in fact, it emerges that only one in four prisoners in Italy participate in sports activities, while participation in cultural and recreational activities involves two out of three prisoners. This gap is attenuated a lot with reference to foreign prisoners, who participate in sports activities in 40% of cases, probably in consideration of the fact that almost all of them are male. In fact, Graph 2, which deals with gender differences, shows how most female prisoners participate in cultural/recreational activities and theatrical workshops, while this proportion is the opposite in the male sub-sample, which in most cases (36% vs. 25%) take part in sports activities.

Several projects are conducted in Italian prisons. Among the virtuous examples of projects, it is worth mentioning “Sport for all in prison” and the “Icaro Project”, implemented by the UISP. These are projects that involve the practice of gymnastics, gentle exercise, oriental disciplines, team games and chess with the main objective of providing opportunities for social recovery of prisoners through total involvement:

The project “Ovaleoltre le sbarre”, developed by the Italian Rugby Federation (FIR) and CONI, has introduced rugby in over 15 national prisons. FIR’s mission is above all to transmit the values of rugby to favour future reintegration into the social reality: the “Progetto Carceri” foresees three Clubs directly

![]()

Table 1. Treatment activities. Year 2017. Absolute values and percentage values on the total. Official data Ministry of Justice.

Graph 1. Type of treatment activities.

Graph 2. Gender comparison for treatment activities.

Graph 3. Participation of foreign prisoners in the treatment activities.

connected to prisons in order to participate in the Italian Serie C Championship and foresees that many others Clubs are committed to spreading the game and the typical style of the “oval ball” in many prison institutions and juvenile institutions throughout Italy.

As stated by a member of the Rugby Union Lawyers: “this sport has taught us that no matter who you are, what you did good or bad in life, the important thing is to be aware that you are practicing a noble sport, with very simple rules, basically knowing how to pass a ball to a partner. Back and then moving forward. The oval ball derives from suffering of the fray and passes from hand to hand, up to the three-quarters area, it goes out, free, in the goal”. And again, the captain of the “Bisonti Rugby”, the rugby team of the prison of Frosinone (who plays in the C league, always in home games), for ten years imprisoned in the Italian institute, explained how “rugby represents a fundamental part of life inside the prison to us. The training sessions, individual and team responsibilities, the obligation to respect the rules of the field are an important moment of growth for us, as athletes and individuals. Rugby has become fundamental in our daily life”. After an interview, another one of them, Renato, says: “Up until now we were on TV for bad things. At least now we can be proud of what is shown. My problems fly away with the ball”.

The “Sport in carcere” project, developed from a collaboration between DAP and CONI following undersigning of the Memorandum of Understanding of 3 December 2013, is also of great interest, aiming at improvement of conditions of life of the prisoners through sports practicing and training. The goal is to promote health and wellbeing thanks to the benefits of physical activity by collaborating in a re-education process through sports. Sport activity can also represent a positive element to contribute not only to the maintenance of a satisfactory state of psycho-physical health, but also to improve cohabitation within the institute, contributing to lowering the level of tensions and conflicts.

Following this orientation, the activities are designed and organized in such a way as to represent an “educational tool”, which allows the beneficiaries of the activities to work on relationships, rules, values such as legality and cooperation; to work on the meaning of defeat and victory and on the management of frustrations. Sport, therefore, becomes a useful transversal tool for operators in the educational strategy of prevention and recovery of prisoners. The main objective to be developed in prisoners is to succeed, through sports activities, in increasing self-confidence, because through the body and movement, players increase awareness of their abilities and realize they can face even complex situations.

To achieve this goal, educators offer exercises commensurate with the skills of learners and with progressive difficulties, using a gradual approach, allowing prisoners not to face obstacles that they are not able to overcome. The social impact of the project is fundamentally connected to returning free citizens to the community who, through a path of re-education, cognition and experience, can enjoy concrete prospects of integration.

In an empirical sense, verifying ex post the results of the projects described, we carried out an interview with the referent of the Educational Area of “Rebibbia Casa di Reclusione”, who told us about a great heuristic experience in order to understand the importance of sport in prison, aimed at social inclusion and reintegration of the prisoner in the “free” society. Below, a brief extract of the interview:

A.N., an Albanian prisoner sentenced to life imprisonment for multiple homicide, in 2010 obtained the “fair play” award from CONI. Captain of the “5-a-side” team of the Rebibbia prison house, the “Roman Internati”, stood out with his teammates for never having been given a warning during the annual participation at the “Palio Roma”, the football tournament that, from 2003 to 2011, included the participation of 400 teams in the capital. The team was awarded three silver medals and one bronze in the 7 years of participation. Accompanied by two AICS operators, he went to collect the prize in the ForoItalico Hall of Honour, obtaining his first “award permit” after 18 years spent in jail. This was one of the many situations that demonstrate the importance of the value of sport in prisons. Above all, the value of the relationship with the external community has been favoured by using sport as a socializing tool.

The history of Penitentiary Pedagogy provides us with the image of young men from the oratory of “Nostra Signora di Guadalupe” in Rome ready to play a football match with the minors of “Casal del marmo”. The story dates back to one Sunday in April 1960. The experimentation was carried out, in strict accordance with the new educational standards of the time, by the Director of that rehabilitation centre, Dr. Luigi Turco, who with a futuristic approach had sensed the educational objective of a relationship that could make the under-aged children of the institution feel as “normal” as possible, confronting their peers. It is a proven fact that sport is the “container” of compliance with the rules. Young drug addicts and drug users rediscover a part of themselves in their relationship with the sporting event. Dismantling of one-self, at the base of deviant processes, is traced back to a renewed identity dimension, thanks to the observance of respect: respect for a code or regulations characterising all sports disciplines.

Through this excerpt of narration, it is possible to return to the most eminently theoretical assumptions, previously evoked: against every cliché, the “fair play” award is won by the unexpected athlete, who is a prisoner guilty of numerous murders; against the clichés, running into a field, can create socialization, can recreate the social roles forgotten for too long in a structure that imprisons; against all odds, kicking a ball (if included in a programme aimed at real individual effectiveness and social impact) can result in the fulfilment of codes of mutual respect and observance of social rules of cohabitation.

5. Findings and Results

The low presence of sports activities in Italian prisons can be attributed to several factors: sport in Italy has been assimilated for a long time—above all because of the narrative that it is made during fascism era—with the competitive spirit of excellence, thus conveying over the years a consequent penalization of the practice in pedagogical and educational terms, areas instead of priorities in the penitentiary sphere. Thus, from a long-term perspective, this marginalization can be attributed to a current assimilation of sporting practice and to the use made of it in the regime in terms of propaganda and militarization.

One hypothesis that can be proposed here is that sport and its practice in Italy is a truly anomalous case, due to the fact that the fascist regime affirmed a dichotomous paradigm of sporting discipline: on the one hand, a “mobilization of bodies” that is expressed in the cult of gymnastic choreographies (with a strong symbolic and ideological imprint) and in the “militarization” of physical activities and skills aimed at combat (shooting, fencing, motoring, etc.). On the other hand, an impressive organizational and financial investment in the top sport whose successes—which took place both in the Olympic competitions of 1932 and 1936 and in professional team sport with the 1934 and 1938 Soccer World Cup, in addition to the most popular individual sports such as cycling and racing—had to exalt national pride and celebrate the regime. Competitive activities and selection of talents were entrusted to a fierce and powerful specialized institute effectively established itself in Italy (the CONI was literally re-founded with this mission in 1926). Inevitably, this cast a shadow over the same CONI, which in the post-war period was equated with the regime organizations and condemned to a dissolution, which never occurred for political strategies; with benefit, it must be recognized, of competitive excellence, but with a further penalization of the practice with educational and preventive purposes.

One of the weak point to be underlined is that very often these activities are oriented more in terms of tournament organizations or occasional meetings (even better if in the presence of authorities), rather than integrated health promotion paths and projects or actions of individual empowerment through sports practices (see Esposito, 2010; Arana, Uriarte, & Bravo-Cucci, 2018). A separate discussion must be made for the female population; as reported by Antigone (2018), in the institutes and in the women’s prison sections we see how the sports offer, although present, is characterized by a contraction in the choice of activities. Among the Institutes visited by the association, volleyball is practiced only in 3 structures, dancing in 7 (including zumba and flamenco); then there is an institute, Rebibbia, where running and fitness are practiced (also in Pesaro). Yoga is practiced in Nuoro. This list seems to return a somewhat stereotypical image of women, so the only team sport practiced is volleyball. But men are victims of the same stereotypes, who seem to be practicing almost exclusively football.

6. Conclusions

Sport in prison is essential for various reasons: physical, to improve the health status of prisoners and to reduce the possibility of contracting diseases (see Talleu, 2011; Vaiciulis, Kavaliauskas, & Radisauskas, 2011; Francis, 2012); psychological, to combat boredom and increase the possibilities of coping and the level of resilience (see Durcan, 2008; Ozano, 2008; Breslin & Leavey, 2019); social, to increase social capital and improve the chances of social and job reintegration (see Coalter, 1996; Balibrea & Santos, 2011; Meek, Champion, & Klier, 2012). Of course, it all depends on how it is planned, managed and implemented: it is not enough to organize meetings, tournaments and matches, but sport must become a true vehicle for new relational and social opportunities (Conley, 2004). Therefore, we need to radically change the thinking around sport, and start interpreting it rather than as a playful pastime, and beyond the professionalism that involves the masses just in terms of audience, as an activity tool for direct expression of one’s personality and as human right, as defined by UNESCO in 1978 in the International Charter of Sport and Physical Education.

The last few years have seen prison become closer to that concept of “social aspirator”, well described by Loic Wacquant (2009), born thanks to the increasingly disruptive criminalization of social marginalization. And so, we must ask ourselves: does prison today make sense as it is? Is the penitentiary system as it is useful to the people who “inhabit” it, and to the whole society? Reducing the basic needs of movement, privacy, autonomy, affectivity, relationships, make the prisoner a better person? The natural response to these rhetorical questions is a negative one. The main theme that emerges from the pages of this article is that of the humanization of punishment: the rights of detained persons must always be respected and protected, not only at the level of empty lexical formality. The right to sport and physical activity, to education, to participate in treatment activities, to socialization and so on are not frills to “flaunt” on public and formal occasions, but must become a true ground zero for a new “penitentiary community” (see Hsu, 2004; Esposito, 2016).

In conclusion, beyond the populistic plans that foresee the construction of new institutes to reduce the phenomena of overcrowding, we believe here that the real problem is the overcoming of the idea of prison, and its replacement possibly with that of “prison community” and with other solutions—even radicals—who disregard the sense of distress experienced today; moving instead towards alternative de-carceration programs, thus overcoming the very concept of “total institution” (Goffman, 1961) and replacing it with alternative social institutions of the Third sector.

NOTES

1https://www.europris.org/wp-content/uploads/Romania-EN-prisoner-information-sheet.pdf.

2http://www.justice.gouv.fr/prison-et-reinsertion.

3http://www.justice.gouv.fr/prison-et-reinsertion,.

4Notes provided by the Penitentiary Administration Department in January 2018.

5Notes provided by the Ministry of Justice, Penitentiary Administration Department, in January 2018.