Influence of Body Dissatisfaction in the Choice of the Career of Student’s New Entry to Nutrition ()

1. Introduction

Several studies have shown that there is an association between students of the degree in nutrition and the presence of symptoms of eating disorders (EDs), revealing mainly higher rates of Body Dissatisfaction (BD) and restrictive and purgative risk behaviors (RB) compared to students of other bachelor’s degrees (Crockett & Littrell, 1985; Kinzl et al., 1999; Torresani, 2003; Cruz et al., 2008; Kolka & Abayomi, 2012).

The factors that influence its development are multiple and these have evolved as technology and society are modernizing. Gender stereotypes are part of these factors as, in most cultures and since ancient times, women have been valued primarily for their physical attributes, these being the core of their identity, as well as the object of desire for others; on the other hand, what makes men more attractive has been based on their abilities and access to power than their physical appearance (Bustos Romero, 2011).

Over time, the canons of beauty in both sexes have been modified, eliminating and integrating concepts and meanings; both men and women have adopted beauty care actions that range from the use of cosmetics, clothing and accessories, to the monitoring of different eating habits and physical activity, however, in some cases they have taken radical measures such as undergoing cosmetic surgeries, monitoring of extreme feeding regimes, risky eating behaviors and performing strenuous exercise (García, 2010).

The theory of social comparison suggests that individuals evaluate themselves by judging others with similar biological characteristics (sex or age), and identifying favorable and unfavorable differences (Festinger, 1954); physical appearance comparisons are the most common and often derive from the influence of other people, including friends, family and the influence of mass media that demand adherence to the standards of ideal beauty and have taken a very important role in the issues of image, because advertising has “sold” the notion that in order to be successful, you need to look like body models that are outside the recommended health standards, these women being slim, and men muscular, so that the population, in their desire to achieve the “ideal” body, is on the verge of following obsessive and health risky behaviors (Bustos Romero, 2011; García, 2010; Fox & Vendemia, 2016).

At the same time, the use of social networks in adolescents and young adults has been widespread in modern times; there are networks based on images such as Instagram, Snapchat and Facebook, which allow you to share and edit visual content as well as find thematic publications through “hashtags” (#); the popularity of users in social networks is measured through followers, friends or by the feedback given in the form of likes or comments (Brea Folgar, 2019); since social networks provide instant access to “selfies”, photos and videos that, in turn, promote thin or muscular bodies as a new lifestyle, ideal of beauty, popularity and acceptance, which may favor social comparison with known, unknown or famous users, as well as the idealization of unreal beauty models, all this can lead to BD (Fox & Vendemia, 2016; Brea Folgar, 2019).

One of the most vulnerable groups to suffer from EDs is university students, since they are subject to various factors that can favor the appearance of BD and even development from various RB, because their lifestyle is modified by the new college environment, where the student first acquires responsibility for their food and is subjected to greater stress, which has been associated with the increase in body weight and unhealthy eating habits, as well as other harmful eating such as skipping meal times, eating snacks between meals, preference for fast food and frequent alcohol consumption (Arroyo Izaga et al., 2006; Gottschalk, Macaulay, Sawyer, & Miles, 1977).

Studies have been found where the relationship between career choice and the EDs, mainly in those professions in which there is sociocultural pressure to maintain a lean and aesthetic body, including: physical education, dance, communication, psychology and nutrition (Torresani, 2003).

In a study conducted by Feitas et al., in 2017 in Portugal, where the objective was to compare the eating behavior of the students of the degree in nutrition with the students attending other courses, a Dutch food behavior questionnaire was used to measure food restriction and emotional and external food consumption; the results showed that there was greater food restriction in nutrition students of both sexes compared to students in other majors; the women of the nutrition career were those who presented higher levels of bingeing compared to those of other courses (Freitas et al., 2017).

Verde Flota et al., 2006 conducted a study where they analysed the responses of 437 surveys for new students in 2004 of medical, nursing, dentistry and nutrition major of the Autonomous Metropolitan University-Xochimilco, in Mexico; it had as an independent variable the introjection of gender stereotypes and as a dependent variable the perception of the chosen degree. The results concerning the degree in nutrition consisted of obtaining statistically significant masculinity traits compared to the nursing and dental degrees, in addition, among the reasons for choosing the degree, where the option “learn to stay healthy” was mainly chosen by the nutrition students in relation to the students of the other majors included in the study (Verde Flota et al., 2006).

For nutrition students, the mastery of knowledge about the properties of nutrients from different foods used to maintain health, prevent and treat diseases placed them in a special place before society, where they are also pressured to comply with impositions related to body image, that is, they must have a thin figure, under the assumption of walking the talk, but from the social configuration, where the thin body image is linked to success and not in the context of health in such a way that, in the published literature, at different times, places, contexts, objectives and methodology similar results are described, where nutrition students have been considered as a risk group for EDs (Torresani, 2003; Kinzl et al., 1999; Crockett & Littrell, 1985; Behar, Alviña, Medinelli, & Tapia, 2007; Gili et al., 2015; Chávez-Rosales, Camacho Ruiz, Maya Martínez, & Márquez Molina, 2012).

It is not known if these RB develop because people were already predisposed before being accepted into the bachelor degree in nutrition and dietetics due to their personal and/or family experiences of weight control, or arise due to increased knowledge on the subject and the belief that appearance is important for future professional success, questioning which resulted in the present study whose aim is to identify the influence of body dissatisfaction (BD) in the career choice of new students of the bachelor’s degree in nutrition compared to those new students of the bachelor’s degree in psychology of Higher Education Institutions (HEI) in Merida, Mexico

2. Methodology

The project to be carried out was presented to the authorities of each HEI and a request authorization to carry it out was filed. The newly admitted students to the bachelor’s degree in nutrition and psychology were grouped in the facilities offered by each institution where the purpose of the research was explained; those who agreed to participate signed the Informed Consent Letter and the Privacy Notice (SEGOB, 2013). Subsequently, the registration of general data: age, sex, degree and institution of origin were registered, as well as six questions related to the reasons why the student chose the career were asked, choosing the three main putting the progressive number from highest to lowest degree of importance.

The Body Image Questionnaire (BSQ) was also applied to identify the presence of BD (Cooper, Taylor, Cooper, & Fairburn, 1987), which consists of 34 questions with 6 answer options: never, almost never, sometimes, quite a few times, almost always and always. Being the international cut-off point of 105, this questionnaire has been validated for Mexican women (Unikel Santocinni, Díaz de León Vázquez, & Riviera Márquez, 2016; Vázquez-Arévalo et al., 2011) where two factors arise: 1) regulatory discomfort, which refers to discomfort with the body shape that is considered normal and does not cause risk for health and 2) pathological discomfort, which is one that causes the appearance of unhealthy behaviors (fasting, vomiting use of laxatives, diuretics, etc.) and that put health and life risk. From this validation, the cut-off point of 110 for the Mexican population was determined.

The Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to analyze the correlation between the BD and the reasons for the career choice, with the support of the STATA v.13 program.

3. Results

Seven Higher Education Institutions from Merida city participated in the study with a total population of 501 new entry students to the degrees of nutrition and psychology; of these, only 471 (94.0%) voluntarily agreed to participate in the research, 60.2% are bachelor’s degree in nutrition, with 40.4% women and 19.8% men. 39.8% were bachelor’s degree in psychology, with a greater number of women (26.3%) than men (13.5%).

Table 1 shows the distribution of the study population according to the

![]()

Table 1. Prevalence of BD in the study population by sex and degree.

M: male; F: female. Source: result of application in Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) study population.

presence of BD was identified through the application of the Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ). It was found that 324 students exceeded the cut-off point of the instrument, which represents an overall BD prevalence of 68.8%.

It can be observed that the prevalence of BD was higher in the students of the degree in nutrition (41.9%) compared to those in psychology (26.9%).

To identify the prevalence by sex, the male results of both bachelor’s degrees were added, as well as the results of the female, finding higher prevalence of BD in women (43.1%) than in men (25.7%).

Table 2 shows the reasons that the students considered most important to the career choose, distributed by degree, sex and the presence or absence of BD.

They choose three options from the six reasons that were in the “General Data”, marking with number one what they considered most important and number two and three in order of less importance.

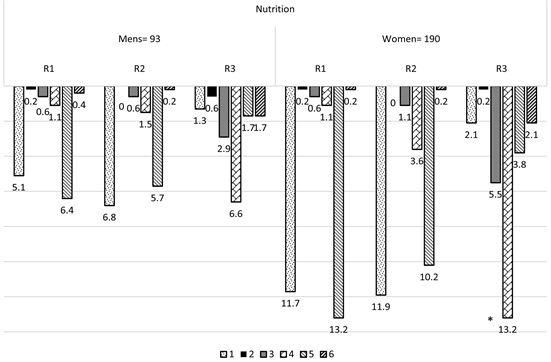

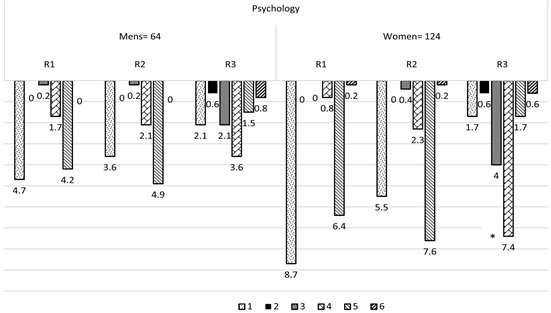

The students who presented BD, who attend the bachelor’s degree in nutrition, both men (6.4%) and women (13.2%) they chose as the most important reason question number five, “Because I like the activities performed by the professional in this degree (providing therapy, learning to eat healthy, preventing diseases, etc.)”, while those of the degree in psychology, men (4.7%) and women (8.7%) chose the first question as more important: “Because I like helping other people (improving their health, solving their problems, etc.).”

As a second reason, the students of the degree in nutrition and dietetics, both men (6.8%) and women (11.9%), chose the first question “Because I like helping other people (improving their health, solving their problems, etc.)” and those of the degree in psychology, both men (4.9%) and women (7.6%) chose as the second most important reason question five “Because I like the activities performed by the professional in this degree (providing therapy, learning to eat healthily, preventing diseases, etc.).”

As a third reason, both the students of the bachelor’s degree in nutrition, men (6.6%) and women (13.2%), as well as those of the bachelor’s degree in psychology, men (3.6%) and women (7.4%), chose four question “Because I don’t feel good myself and expanding my knowledge during the career, I may improve what bothers me (my relationship with others, my self-esteem, my weight, my

![]()

Table 2. Reasons for choosing the career according to the presence of CI, by sex and agree.

Source: result of the application in the study population of the Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) and “General data”.

physical appearance, my silhouette body, etc.).”

It can be observed that there is a coincidence between the students of the two bachelor’s degrees when considering this option among the three most important, which means that 30.8% of the study population with BD, does not feel good about themselves and chooses the profession to use the knowledge of the career to improve what bothers you.

The frequency was higher in students of the bachelor’s degree in nutrition (19.8%) compared to those in psychology (11.0%), being highest in women (20.6%) than in men (10.2%) and higher in women of nutrition (13.2%) compared to psychology (7.4%).

On the other hand, the students who did not present BD, chose as the most important reason question one, “Because I like to help other people (improving their health, solving their problems, etc.)”; This result was presented in the same way in men (2.1%) and women (5.5%) of the bachelor’s degree in nutrition than the bachelor’s degree in psychology (1.1% and 4.7% respectively).

As a second reason they chose question five “Because I like the activities performed by the professional in this degree (providing therapy, learning to eat healthily, preventing diseases, etc.)”, coinciding in men and women of the two bachelor’s degrees in nutrition (2.1% and 4.7%) and in psychology (1.1% and 4.7% respectively).

As a third reason, men (2.3%) and women (6.1%) of nutrition as men (1.1%) and women (5.1%) of psychology career choose question four “Because I don’t feel good about myself and when expanding my knowledge during the career, I can improve what bothers me (my relationship with others, my self-esteem, my weight, my physical appearance, my silhouette, etc.)”, presenting a 14.6% higher frequency students in nutrition (8.4 %) than students in psychology (6.2%) and with higher frequency in women of both degrees (6.1% and 5.1%) respectively.

It is noteworthy that the two groups with BD and without BD, have chosen question four within the three main reasons for choosing the career, presenting a general frequency of 45.4% of the population, being higher in students with BD (30.8%), so it could be said that the BD has an influence on the choice of the career.

The reasons (R) for choosing the career by sex were compared, using the Pearson’s Chi-square test. In Graph 1, shows that there is a significant difference (p = 0.001) in reason three (question four) “Because I don’t feel good myself and by expanding my knowledge during the career, I can improve what bothers me (my relationship with others, my self-esteem, my weight, my physical appearance, my silhouette, etc.)” between men and women of the bachelor’s degree in nutrition.

In Graph 2 the comparison was made with the students of psychology, finding significant difference (p = 0.001) between men and women also in reason three (question four), “Because, I do not feel good about myself and when expanding my knowledge during the career, I can improve what bothers me (my relationship with others, my self-esteem, my weight, my physical appearance, my silhouette, etc)”.

Therefore, it can be inferred that the presence of BD in women has a significant influence on the choosing of careers in both degrees’ nutrition and psychology. This is possible to opt for this type of careers because they have symptoms of BD with what they do not feel comfortable and consider that they may improve with the knowledge and skills they acquire during their bachelor’s degree.

4. Discussion

Much has been said about the relationship between the presence of BD and the symptomatology of EDs degree in nutrition, as a result of research that has been conducted in groups of students from different universities around the world,

Graph 1. Comparison percentage of the reasons (R) of the choice of the nutrition race by sex. Reasons for choosing the race: 1. Because I like to help other people (improve their health, solve their problems). 2. Because my Parents forced me. 3. Because I consider that I did not find another option. 4. Because I don’t feel good about myself and by expanding my knowledge during the race I can improve what bothers me (my relationship with others, my self-esteem, my weight, my physical appearance, my silhouette). 5. Because I like them the activities of the professional of this career (provide therapy, learn to eat healthy, prevent diseases). 6. To follow the profession of my parents or another family member. *p = 0.001.

Graph 2. Comparison percentage of the reasons (R) for the choice of the psychology career by sex. Reasons for choosing the career: 1. Because I like to help other people (improve their health, solve their problems). 2. Because my parents forced me. 3. Because I consider that I did not find another option. 4. Because I don’t feel good about myself and by expanding my knowledge during the race I can improve what bothers me (my relationship with others, my self-esteem, my weight, my physical appearance, my silhouette). 5. Because I like them the activities of the professional of this career (provide therapy, learn to eat healthy, prevent diseases). 6. To follow the profession of my parents or another family member. *p = 0.001.

some of them only considering women, others women and men and sometimes contrasting the findings with other careers as a comparison group (Crockett & Littrell, 1985; Torresani, 2003; Cruz et al., 2008; Laus, Moreira, & Costa, 2009; Chávez-Rosales, Camacho Ruiz, Maya Martínez, & Márquez Molina, 2012; Kolka & Abayomi, 2012; Mealha, Ferreira, Guerra, & Ravasco, 2013; Meza Peña & Pompa Guajardo, 2013; Nergiz-Unal, Bilgic, & Yabanci, 2014; Harris et al., 2015). However, it is still unclear whether the presence of BD and EDs symptoms were present before entering to the career or developed as a result of the knowledge and skills learned during the course of their professional preparation.

This study included new students entering of both sexes from the nutrition degree of seven universities in the City of Merida and as a comparison group to those of the psychology degree of the same participating universities.

It was found that 68.8% of the participants present BD, higher bachelor’s degree in nutrition (41.9%) compared to bachelor’s degree in psychology (26.9%) and higher in women (44.1%) than in men (25.7%), especially in nutrition career. This prevalence is highest than that reported by Bosi et al., in a study conducted in 2006 where it found a prevalence of 59.6%; research by Laus, Moreira, & Costa (2009) reported 42%, while Garcia Ochoa in 2010, found prevalence of 60.5%. A study conducted by Salgado Espinosa & Álvarez Bermúdez in 2018, was presented a prevalence of 63% and Medina-Gómez et al. (2019), in a study with university students found a prevalence of 61.4%, higher in women than in men. Only the study conducted by Sampaio, Parente, Carioca, & Jiménez Rodríguez, conducted in 2018, reported a higher prevalence, 89.5%.

The results of most research coincide in the prevalence of BD in female, therefore, it is thought that although the social pressure for ideal beauty models has gained strength in the male population, it is the women who it continues to affect more, so they are still the most likely to develop EDs (Soto et al., 2013; Trejo Ortíz et al., 2010; Zagalaz, Romero, & Contreras, 2002).

BD is a predisposing factor for EDs as stated by different studies carried out throughout the world (Sansone, Wiederman, & Monteith, 2001; Lameiras Fernández, Calado Otero, Rodríguez Castro, & Fernández Prieto, 2003; Casillas-Estrella, Montaño-Castrejón, Reyes-Velázquez, Bacardí-Gascón, & Jiménez-Cruz, 2006; Lim, Thomas, Bardwell, & Dimsdale, 2008; Meza Peña, & Pompa Guajardo, 2013). It is considered a mediating variable between the social pressure that exists in women to maintain a certain body image and the establishment of EDs and has come to be considered as a previous factor, in addition to being used internationally as a criterion for its diagnosis, which is reinforced by the mass media and the fashion industry, which have an impact the self-esteem on adolescent’s until they are thought that not being thin or beautiful, they will not be accepted in society (Baile Ayensa, Guillén Grima, & Garrido Landívar, 2002; Derenne & Beresin, 2006).

According to statistics, 23% of women in Latin America have BD (Rodríguez & Cruz, 2008); this may be due to the fact that there is socio-cultural pressure on the profession to maintain healthy habits, such as performing physical exercise, bring a correct diet, maintaining the body slender, interpreting together as a synonym for “professional success” (Chávez-Rosales, Camacho Ruiz, Maya Martínez, & Márquez Molina, 2012).

The highest prevalence of BD in students who have just started the nutrition career, the result of this research, suggests that their choice of profession might be influenced by the presence of BD.

As the first reason to choose the bachelor’s degree in nutrition who presented BD chose “Because I like the activities performed by the professional in this degree (providing therapy, learning to eat healthily, preventing diseases, etc.)”, reason that the psychology students chose Secondly. The option “Because I like helping other people (improving their health, solving their problems, etc.)” was chosen as number one in bachelor’s degree in psychology and two in nutrition degree; this coincides with a study conducted in 2005 by Hughes & Desbrow (2005), who state that the reasons for studying nutrition and dietetics were “interest in nutrition, health, helping people and disease of family, personal or other important people such as their mothers and teachers”. It also coincides with the study conducted by Coronel Núñez, Pineda Sales, Díaz García, & Reyes Méndez (2019) where the most commonly chosen reasons for nutrition students were “The interest in helping people” and “The taste for the career”, while the option “To improve your body image” was found in the third order of importance, which coincides with the present investigation in which, both the nutrition and psychology degree chose as a reason three “Because I don’t feel good about myself and by expanding my knowledge during the race, I can improve what bothers me (my relationship with others, my self-esteem, my weight, my physical appearance, my silhouette)”.

It is noteworthy that, of the three reasons, that the nutrition degree presented more frequently in the third (19.8%): “Because I don’t feel good about myself and by expanding my knowledge during the race, I can improve what bothers me (my relationship with others, my self-esteem, my weight, my physical appearance, my silhouette)”. while in psychology degree it was the lowest (11.0%). Presenting in the two degrees has significant difference between women and men.

Students who did not present BD both nutrition and psychology degree, their chose the same reasons as those who presented BD but at very low frequencies, so it could be affirmed that BD has an influence on the choosing of the nutrition career, which coincides what they said Korinth, Schiess, & Westenhoefer (2010), in their study, finding that students who have problems with food are admitted to the nutrition career. Other authors, such as Hughes & Desbrow (2005), found that the main reasons that motivated to 30% of applicants to study nutrition at a university in Australia were: family experiences (me, family or friends) with obesity, eating disorders or both of them; this leads to approaches related to the profession and ethics, because it represents a risk for the student who has these unsolved problems and for the trainers of professionals, since previous experience with these disorders compromises the student’s competence for the care of these patients in the future.

Lordly & Dubé (2012), conclude in a study by people with eating disorders are peculiarly interested in food and are always worried about it and that they are usually interested in careers in the field of nutrition.

5. Conclusion

The results of the present study, where the prevalence of BD and the choice within the main reasons to pursue the career are personal situations such as dislike with weight, physical appearance and silhouette, offer a more robust support to affirm that 41.9% of the aspirants to nutrition degree of the HEI from the city of Mérida who participated in the study, chose the career under the influence of BD.

This situation places the candidates for the bachelor’s degree in nutrition as a vulnerable population, so the selection process for entering the career must be more careful, giving the opportunity to further assess the student’s motivation for the career and their expectations regarding the profession, since the ethical implications regarding whether it is appropriate or not for a student detected with BD or symptomatology of EDs to be admitted, may take incalculable dimensions from a legal and professional point of view due to the repercussion that can have from a personal aspect, if you have not solved the problem, as in the care of your patients.

Limitations

- The study is only valid for the population under investigation. It is not representative for any population.

- The fact that participation in the study is voluntary may favor the exclusion of individuals with risk behaviors or bodily dissatisfaction, who may refuse to participate.

- There may be other reasons for the choice of the career; in the present study the most common previously identified in students of the health area was included.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Nutrition and Psychology undergraduate students who collaborated in the data collection, the academic and administrative authorities of the Faculty of Medicine of the Autonomous University of Yucatan, for all their support and facilities granted in the making of this project, specially the anthropologist teacher Erick Padilla Lizama; the academic authorities of Higher Education Institutions in Mérida, Yucatán, Mexico; as well as the parents and students who participated and were the reason for this study.