How Do Background Factors Influence Children’s Attitudes toward Gays and Lesbians? ()

1. Introduction

Many researches have been focused on adults’ attitudes and prejudice toward gays and lesbians. However, due to the sensitive and complex nature of this topic, children’s perspectives have yet to be thoroughly analyzed. To truly understand the existing prejudice and attitudes that the society holds toward gays and lesbians, the source has to be traced back to the early formation of prejudice, if there is any, during children’s early developmental stage. Though the inclination of choosing and favoring ingroup members than outgroup members has been proved to arise early in the infant stage (Jin & Baillargeon, 2017) , the formation of prejudice seems to be influenced by infants’ contact with the world. A research by Carol Lynn Martin and Diane Ruble indicates that young children are always actively searching for gender cues to form gender cognitions including gender identity and gender stereotypes to help them understand and make sense of the world (Martin & Ruble, 2004) . Through gender socialization and contact with the outside world, children categorize the information that they gathered to make broad assumptions about each gender as a starting process of the formation of gender prejudice and attitudes. This information gives rise to our research question of whether the same result of societal influences can be applied to children’s formation of attitudes and prejudice toward lesbians and gays. In this paper, we will be analyzing six background factors as potential influences on children’s attitudes and prejudice toward gays and lesbians: age, gender, religion, media exposure, parents’ attitudes, and teachers’ attitudes (influence of education) toward gays and lesbians.

Research objectives:

1) To investigate whether there is a relationship between children’s attitudes toward lesbians and gays and their surrounding environment, such as religious beliefs, their parents’ attitudes and teachers’ attitudes toward gays and lesbians.

2) To investigate whether children’s age and gender have a relationship to their attitudes toward lesbians and gays.

3) To investigate whether the amount of media exposure children received is related to their attitudes toward lesbians and gays.

4) If there is an relationship, which factor or factors have stronger relationships with their attitudes toward lesbians and gays.

2. Literature Review

During the developing age, children’s perspective toward the world changes rapidly as they constantly learn and observe the society around them. This is a critical period for analyzing any prejudice that they form. Baker and Fishbein observed that older students were less negative toward gays and lesbians than were the younger ones (Baker & Fishbein, 1998) . This developmental trend is explained by Martin and Ruble as they analyze the developmental patterns for the formation of gender cognitions. Developmental changes, especially children’s changing cognitive abilities in understanding of gender and their evolving understanding of concepts, is a major aspect of cognitive theories of gender (Martin & Ruble, 2004) . Evidence shows a developmental pattern that can be characterized by three overall phases (Trautner et al., 2003) . Figure 1 shows

![]()

Figure 1. A model of phase changes in the rigidity of children’s gender stereotypes as a function of age.

their suggested idea that the learning of gender categories associated with the broad generalization of different genders leads to stereotype formation, thus resulting in a period of very rigid beliefs toward certain groups. This is followed by more flexible beliefs as the children continue to learn about the different groups (Martin & Ruble, 2004) . Applying this developmental pattern theory on attitudes and prejudice toward gays and lesbians explains the phenomenon that Baker and Fishbein observed on children’s change in attitudes toward gays and lesbians as they age. We thus hypothesize that an increase in children’s age will show a reduce in their prejudice and negative attitudes toward gays and lesbians. In this case, we are only analyzing children from age 6 to 10.

Many literatures have shown that heterosexual men show more hostile attitudes toward gay people than heterosexual women (Herek, 1994) ; and each sex has generally more negative attitudes toward homosexual person of their own gender (Holler, 2012) . One explanation for this phenomenon is that females have greater tolerance than males for discrepancies from socially prescribed gender roles (Fishbein, 1996) . Thus, we are analyzing different genders’ attitudes toward gays and lesbians separately, hypothesizing that boys will show a more negative attitudes toward gays; girls will show a more negative attitude toward lesbians; and boys will generally show more negative attitudes toward gays and lesbians than girls.

Furthermore, Stover and Morera suggest that increased religious involvement is an indicator for higher sexual prejudice. In the study, people who identified themselves as very religious do not have distinct level of prejudice toward gays and lesbians. As individuals become less religious, the statistics suggest that there is a difference between the level of prejudice toward gays and lesbians (Stover & Morera, 2007) . To investigate whether religious affiliation serves as an influential background factor on children’s attitudes toward gays and lesbians, their religiosity was assessed. We hypothesize that religiosity has a direct relationship with the level of children’s prejudice and attitudes toward gays and lesbians.

With the prevalence of technology and lower ages of access to social media and media in general, the younger generations have distinctly different experience from generations before them. The more open publicity of gay culture TV shows, movies, and celebrities combined with children’s increasing exposures to the media result in an increase in media exposure of the topic of gays and lesbians. Contact hypothesis suggests that the contact with multiple gays and lesbians and the closeness of the relationships are important predictors of positive attitudes (Herek & Capitano, 1996) . The increase in contact with gays and lesbians “normalizes” the minority group, making it less stigmatized. With the extensive availability of pop culture among young children, we hypothesize that the increase in media exposure including gay and lesbian celebrities, TV shows, and movies to children will decrease the level of their prejudice and negative attitudes toward lesbians and gays.

Moreover, studies show that family members can influence children and contribute to the development of prejudice for children between the ages of 6 to 16 years, a critical stage of the development of prejudice in human (Allport & Kramer, 1946) . Prejudice that develops in childhood may potentially matures into adult prejudice and discriminatory practices (Holler, 2012 ) . Since during the age range from 6 to 10, parents and caregivers are likely to spend most of the time with their children, thus having a greater influence on children’s development of prejudice. Parents’ and caregivers’ attitudes toward gays and lesbians might subconsciously influence the children’s attitudes toward these groups. Thus we hypothesize that caregivers’ attitudes toward gays and lesbians will have a positive relationship with their children’s attitudes toward the groups.

Similarly, another group of people that spend a large proportion of time with the children during the critical prejudice developmental stage is teachers at school, who might also have significant influences on children’s attitudes toward gays and lesbians. Thus we expect that the analyzation of teachers’ attitudes toward gays and lesbians would yield a positive relationship with children’s attitudes toward these groups.

Overall, we expect that age and media exposure will have negative relationships with children’s attitudes toward gays and lesbians. Religiosity, parents’ and teachers’ attitudes toward gays and lesbians will have positive relationships with children’s attitudes toward these two groups. We expect that media exposures and teachers’ attitudes toward gays and lesbians will have the most significant influences on children’s attitudes.

3. Methods and Materials

The participants of this experiment were sampled from one local elementary school in United States. Researchers got permission from the school, teachers, and parents to proceed the experiment. The parents’ of the recruited participants signed the Informed Consent Form (Appendix A) to let their children participate in the study. Participants were informed of their right to decline to participate in the study.

3.1. Participant

The total recruited participants are 100 children, with the age of 6 to 10 years old. Each of the five ages has sample size of n = 20 participants. The total number of male and female participants is 50 children each. This study will only be discussing about the participants’ biological gender (male or female) since the children in our sample are too young to answer their gender identity. Table 1 displays the demographic factors of the participants’ age and gender.

3.2. Design

A questionnaire will be used in this study. Part one of the questionnaire is designed for the children to answer, while the second part of the questionnaire includes the questions for their parents to answer. Pictures in Appendix D will be provided with the questionnaire for children to look at then answer the questions related to media exposure category. Pictures in Appendix E will be provided with the questionnaire for children to look at then answer the questions regarding their general attitudes toward lesbians and gays, serving as a demonstration of the scenarios mentioned in the questionnaire.

3.3. Measure

A new survey (Appendix B and C) is generated for this study to measure children’s attitudes toward lesbians and gays. This survey includes demographic measures of age and gender, social exposure measures, educational measures, and children’s attitudes measures. Most of the measures are answered by a 5-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate more positive attitudes toward gays and lesbians.

Social exposure is measured by children’s religiosity and social media exposure that the participants have received. Children participants were asked two questions assessing their religiosity: 1) “Do you think you are a very religious person?” The children were asked to choose an answer from the 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 2 = a little bit, 3 = moderate, 4 = quite a lot, 5 = very). 2)

![]()

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants (n = 100).

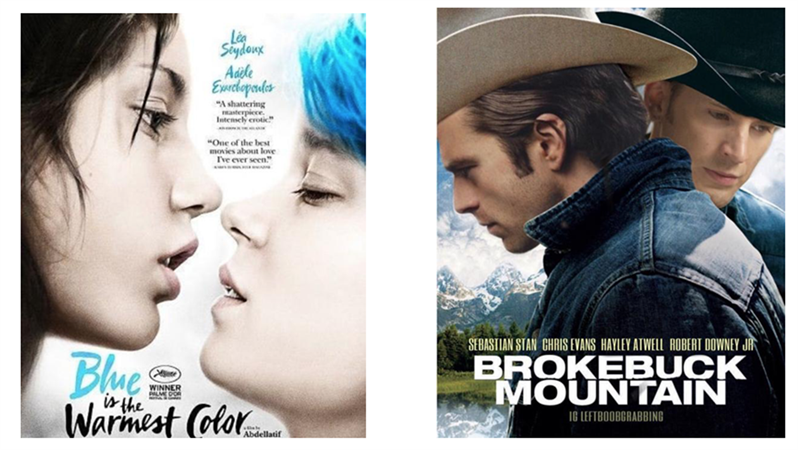

“How many religious events do you take part in a month?” The children were asked to choose an answer from the 5-point Likert scale (1 = 0 event 2 = 1 - 3 events, 3 = 4 - 6 events, 4 = 7 - 9 events, 5 = more than 10 (include 10) events). To evaluate children’s levels of social media exposure on the topic of gays and lesbians, the participants were asked to identify how many gay and lesbian celebrities they know out of 10 celebrities provided in the questionnaire and how many TV shows and movies about gays and lesbians they have watched out of the 10 provided TV shows and movies (Appendix D). The number of the items they identified will be added up together and correspond to a 5-point Likert scale (1 = 0 - 4 items identified, 2 = 5 - 8, 3 = 9 - 12, 4 = 13 - 16, 5 = 17 - 20).

Educational measure was evaluated through teachers’ attitudes and parents’ attitudes toward gays and lesbians. Children were asked two questions to assess teachers’ attitudes toward gays and lesbians. “If a book contains gay/lesbian characters or scenes, do you think your teacher will recommend this to you?”. Children responded based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly not, 2 = maybe not, 3 = not sure, 4 = maybe yes, 5 = strongly yes). The second question is “Compare to heterosexual classmates, what is your teacher’s attitude toward students in gay/lesbian group?” Children responded based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = surely prefer heterosexual students, 2 = may prefer heterosexual students, 3 = not sure, 4 = may prefer gay/lesbian group, 5 = surely prefer gay/lesbian group). In this questionnaire, the expression of “gay/lesbian” indicates that children respond to the same question twice, acquiring their attitudes toward gays and lesbians separately. Parents’ attitudes toward gays and lesbians were assessed by asking two questions to the children participants’ parents directly. “If a book contains gay/lesbian characters or scenes, do you think you will recommend this to your children?”. Parents responded based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly not, 2 = maybe not, 3 = not sure, 4 = maybe yes, 5 = strongly yes). The second question is “How willing are you to make a gay or lesbian friend?” Parents responded based on a 5 point Likert scale (1 = strongly refuse, 2 = may refuse, 3 = not sure, 4 = may willing, 5 = strongly willing).

Finally, children’s attitudes toward gays and lesbians separately were evaluated by showing several pictures (Appendix E) to help the children to understand and answer the 4 questions in the questionnaire. 1) “If there are two gay men, a man loves another man, and they want to get married. What is your feeling about this?”. 2) “If there is a gay couple, two men get married, and they want to adopt a baby. What is your feeling about this?”. 3) “If there are two lesbians, a woman loves another woman, and they want to get married. What is your feeling about this?”. 4) “If there is a lesbian couple, two women get married, and they want to adopt a baby. What is your feeling about this?”. All four questions were answered based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly don’t like, 2 = may not like, 3 = not sure, 4 = may like, 5 = strongly like). A picture about a gay couple and a picture about gay couple got married and want to have a baby were used to illustrate the first two questions. A picture about a lesbian couple and a picture about lesbian couple got married and want to have a baby were used to illustrate the last two questions. A colorful scale (Appendix E) will be used for children to answer all of the 5 point Likert scale questions in the questionnaire.

3.4. Analysis Method

After gathered the data, we categorized and plot the data to calculate and compare the correlation of different measures.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Age

By plotting the age of the boys and girls against their score of prejudice toward lesbians and gays, we get a linear regression of the relationship between age and score of prejudice as shown in Figure 2. The average prejudice score of girls toward lesbians and gays is 3.305, while the average prejudice score of boys toward lesbians and gays is 2.945. The correlation coefficient of the relationship between age and girl’s prejudice score toward LG group is 0.608, having a higher correlation coefficient than the relationship between age and boy’s prejudice score toward LG group, which is 0.438. The correlation indicates that the relationship between girl’s prejudice score and age is stronger than the relationship between boy’s prejudice score and age. Both of these relationships show a positive linear relationship, suggesting that the greater the age, the higher the score of prejudice. Higher score of prejudice indicates a more positive attitudes toward lesbians and gays.

This result shows that the greater the age, the less prejudice the children will be toward lesbians and gays. This result is consistent with what Baker and Fishbein observed in their study. One explanation of this phenomenon can be inferred from the result that Hood (1973) , MacDonald (1974) and Smith (1971) concluded for adult participants, which stated that high rigidity is associated with more “anti-homosexual” sentiment. The developmental pattern theory that

![]()

Figure 2. Correlation between age and score of prejudice.

Martin and Ruble suggested for children’s formation of gender cognition supported this result. They concluded that in early childhood, children are constantly searching for gender cues and absorbing information to categorize different gender groups in order to distinguish and make sense of the world (Martin & Ruble, 2004) . Similar with gender cognition, if children are surrounded by more heterosexual people, heterosexual relationships are social norms for them. Any ambiguity in gender categorization or sexuality norms in this case could serve against children’s categorization, thus resulting in a higher rigidity of beliefs and a higher prejudice toward lesbians and gays in this early stage. However, as children keep learning about different groups and their characteristics, they gain more understanding of the different groups (heterosexual and homosexual), which allows more ambiguity in terms of categorization, followed by a decrease in prejudice toward lesbians and gays. Moreover, the phenomenon of girls having a higher correlation than boys could be explained by Baker and Fishbein’s discussion that “females relative to males become more flexible about sex roles with increasing age” (Baker & Fishbein, 1998) . In our study, we believe that the previous statement could be extended from sex roles to sexuality.

4.2. Gender

Table 2 shows the attitudes of girls and boys toward gays and lesbians separately. Girls’ average prejudice score toward lesbians is 3.45, higher than their average prejudice score toward gays, which is 3.28, indicating that girls possess a higher average prejudice score toward lesbians (their own sex) than toward gays (their opposite sex). Similarly, boys have an average prejudice score of 3.13 toward gays (their own sex), higher than their average prejudice score of 3.02 toward lesbians (their opposite sex). The result shows that children hold more prejudice and negative attitudes toward homosexuals of their opposite sex than of their own sex. Moreover, the average score of prejudice for girls against lesbians and gays is 3.305, while the average score of prejudice for boys against lesbians and gays is 2.945. Since boys show a lower prejudice score than girls, this indicates boys show stronger prejudice toward lesbians and gays. One possible explanation for this pattern is that males have more to lose than females by challenging traditional sex roles (Fishbein, 1996) , while females are more acceptable to the discrepancies in gender role (Baker & Fishbein, 1998) .

4.3. Religion

Figure 3 shows the relationship between children’s religiosity and their score of prejudice. The graph shows a relatively strong negative correlation with a correlation coefficient of r = −0.682. Higher score of religiosity represents children are more religious, and lower score of religiosity represents children are less religious. Higher score of prejudice represents more positive attitudes toward lesbians and gays, while lower score of prejudice represents children holds more prejudice toward lesbians and gays. In the relationship shown in Figure 3, higher score of religiosity correlates with lower score of children’s prejudice. This

![]()

Table 2. Average score of girls’ and boys’ attitudes toward lesbians and gays separately.

![]()

Figure 3. Correlation between prejudice and religiosity.

indicates that the more religious the children are, the more prejudice they hold against lesbians and gays, showing actually a positive correlation between the two factors. One possible explanation for this result is that the values of the predominant religions in the United States are against homosexuality and see homosexuality as guilty. Though the values and opinions around the topic of homosexuality have been progressed, there are still many people deeply under the influence of the religion and the religious values that they practice. Under such influence, it is easy that people hold negative opinions and more prejudice against lesbians and gays.

Moreover, the more frequent one participate in religious events, there are more opportunity for the child to get exposed to the values of the religious people around them. The religious people that they contact with are likely to hold strong beliefs in their religion, thus holding negative opinions toward lesbians and gays. The years of the young children that we sampled are too young to fully understand the religious values that they practiced. As a result, to simply follow their innate instinct and tendency of following ingroup rules, they are more likely to also hold negative opinions toward lesbians and gays.

4.4. Media Exposure

The score of social media exposure and the score of children’s prejudice show a strong positive relationship, with a correlation coefficient of r = 0.851 (See Figure 4). Among all the background factors that we analyzed, media exposure shows the strongest trend. The greater the score of social media exposure, the greater the score of children’s prejudice, indicating that an increase in social media exposure correlates with a decrease in children’s prejudice toward lesbians and gays.

![]()

Figure 4. Correlation between social media exposure and prejudice.

4.5. Parents’ Attitudes

Figure 5 shows the relationship between the score of parents’ attitudes toward lesbians and gays and the score of children’s prejudice. The relationship shows a strong positive correlation of r = 0.744, meaning that the more positive the parents’ attitudes toward lesbians and gays, the more positive the children’s attitudes toward lesbians and gays. One possible explanation of this result is that parents serve as role models for children as they grow up. Children are likely to imitate their parents as a way of learning. As a result, if parents hold strong prejudice and negative attitudes toward lesbians and gays, this could also greatly influence their children’s attitudes toward LG group, resulting in more negative attitudes. Moreover, parents who hold strong prejudice toward LG group are more likely to expect their children to stay in their traditional gender roles and sexuality. This could result in children’s formation of negative attitudes toward lesbians and gays as a result of strong gender role beliefs. In addition, contact theory could also be applied here. If the parents are more friendly and accepting to lesbians and gays, their children might have greater contact with LG people in their parents’ social circle. More contact suggests more positive attitudes toward LG group (Costa, Pereira, & Leal, 2014) .

4.6. Teachers’ Attitudes

Similar to parents’ attitudes toward lesbians and gays, teachers also serve an important role in children’s development. Figure 6 shows a strong positive correlation of r = 0.826, meaning that the more positive the teachers’ attitudes toward lesbians and gays, the more positive the children’s attitudes toward lesbians and gays. Contact theories and modelling can also be applied here. At primary school, teachers also spend most of the time with the children, playing a critical role in their education and development. Teachers’ attitudes toward lesbians and gays can greatly and subconsciously influence children’s attitudes toward LG group. Teachers who hold more prejudice toward lesbians and gays might subconsciously force their students to follow the traditional gender role, resulting in children’s formation of prejudice toward the LG group.

![]()

Figure 5. Correlation between prejudice and parents’ attitudes.

![]()

Figure 6. Correlation between prejudice and teachers’ attitudes.

5. Conclusion and Outlook

In general, for both boys and girls, the greater the age, the more positive attitudes toward gays and lesbians. Boys show more prejudice toward lesbians than gays; girls show more prejudice toward gays than lesbians. Compare to girls, boys show overall more negative attitudes toward lesbians and gays. The more religious the children are, the more prejudice they hold against lesbians and gays. Media exposure has the strongest influence within the six background factors that we analyzed on children’s opinion toward gays and lesbians. An increase in social media exposure correlates with a decrease in children’s prejudice toward lesbians and gays. The more positive the parents’ attitudes are toward lesbians and gays, the more positive the children’s attitudes are toward LG group. Similarly, the more positive the teachers’ attitudes are toward lesbians and gays, the more positive the children’s attitudes are toward lesbians and gays. Overall, age and media exposure have negative relationship with children’s levels of prejudice against gays lesbians; religiosity, parents’ and teachers’ attitudes toward gays and lesbians have a positive relationship with children’s attitudes toward these two groups. Media exposures have more significant influences on children’s attitudes.

For the limitations of this study, firstly, it is geographic limitation, as we only sampled children from one primary school in one state of the United States, which is not a comprehensive representation of all primary schools in the country. Future design should take the political stances of each state into account, which could potentially influence the accuracy of data. Considering the age of the participants, there is a chance that the children at the age of 6 - 10 have difficulties understanding the questions in the questionnaire. Misinterpretation of the questions might introduce confounding variables and inaccurate results to the study. Future design should improve on the clarification of the questionnaire. Secondly, children’s change of their attitudes might not solely because of age, instead, the changes could be resulted from the rapid circulation of information in the society.

Furthermore, in this study, we assumed that the participants do not have a clear idea about their sexuality due to their age and the sensitivity of the question. However, there could be exceptions, which could potentially result in ingroup bias that homosexual individuals possess toward homosexual groups.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Yarrow Dunham from Yale University who provided insight and expertise that greatly assisted the research. We thank CIS program for their assistance with the review of the manuscript.

Appendix A

Informed Consent Form

This is an invitation to participate in a research study. We ask you to read this form and ask any questions you may have before agreeing to help us complete this study.

The purpose of this study is to understand children’s attitudes towards gays and lesbian. If you agree with this, please sign this informed consent, then we will invite your kids and you to answer some questions. You can have a look at the questions your kids need to answer in advance. You and your kids have right to quit anytime during this process if you feel uncomfortable.

With confidentiality, the record will only be used for our study and we promise we will keep it private. We won’t record you and your kids name and other private information. Only researchers in this study can access the records.

If you want to know the result of our study, please check here and we will send the result to you through email.

If you read the above information and agree to let your kids and you participant our study, please sign here.

Signature: _________________ Date: _______________

Appendix B

Questionnaire (for researchers and children’s use)

Part one (ask children)

NO.___________

Age:

Sex: □ male □ female

If there are two gay men, a man loves another man, they want to get married. What is your feeling about this?

□ strongly don’t like □ may not like □ not sure □ may like □ strongly like

If there is a gay couple, two men get married, and they want to adopt a baby. What is your feeling about this?

□ strongly don’t like □ may not like □ not sure □ may like □ strongly like

If there are two lesbians, a woman loves another woman, and they want to get married. What is your feeling about this?

□ strongly don’t like □ may not like □ not sure □ may like □ strongly like

If there is a lesbian couple, two women get married, and they want to adopt a baby. What is your feeling about this?

□ strongly don’t like □ may not like □ not sure □ may like □ strongly like

Religiosity:

Do you think you are a very religious person?

□ not at all □ a little bit □ moderate □ quite a lot □ very

How many religious events do you take part in a month?

□ 0 □ 1 - 3 □ 4 - 6 □ 7 - 9 □ more than 10 (include 10)

Social media exposure:

□ 0 - 4 □ 5 - 8 □ 9 - 12 □ 13 - 16 □ 17 - 20

How many celebrities do you know in these pictures? ____________

How many TV shows or movies you have watched before? ___________

Teachers’ attitudes:

If a book contains gay/lesbian characters or scenes, do you think your teacher will recommend this to you?

□ strongly not □ maybe not □ not sure □ maybe yes □ strongly yes

Compare to heterosexual classmates, what is your teacher’s attitude toward students in gay/lesbian group?

□ surely prefer heterosexual students □ may prefer heterosexual students □ not sure □ may prefer gay/lesbian group □ surely prefer gay/lesbian group

Part two (ask parents)

Parents’ attitudes:

If a book contains gay/lesbian characters or scenes, will you recommend this to your children?

□ strongly not □ maybe not □not sure □ maybe yes □ strongly yes

How willing are you to make a gay or lesbian friend?

□ strongly refuse □ may refuse □ not sure □ may willing □ strongly willing

Appendix C

Questionnaire-P (for parent use)

NO.___________

1) If a book contains gay/lesbian characters or scenes, will you recommend this to your children?

□ strongly not □ may not □ not sure □ may yes □ strongly yes

2) How willing are you to make a gay/lesbian friend?

□ strongly refuse □ may refuse □ not sure □ may willing □ strongly willing

Appendix D

Pictures of Celebrities and TV Shows

Celebrities

TV Shows

Appendix E

Illustrations of Gays and Lesbians Scenarios