Analyzing Direct and Indirect Effects of Economic Sanctions on I. R. Iran Economic Growth: Focusing on the External Sector of the Economy ()

1. Introduction

One of the economic and political means of imposing the demands of a country or in other words, meeting its interests by another country is the use of sanctions. In this case, a great and politically and economically influential country may be able to impose economic and political costs on a smaller state through implementing restrictions on that smaller and less influential country and this can be intensified if other great actors of the world of politics and economy cooperate with that sanctioning country, a situation that may be expected for the sanctions imposed on Iran’s economy. Considering the importance of this issue, in this paper, we will look into the effects of economic sanctions on Iran’s economic growth.

In this article, at first we have a look at economic sanctions against Iran and review research literature. Then, we analyze growth models and so the model for this study is developed based on the theoretical assumptions and frameworks concerning economic growth models. Then in the methodology section, the self-explanatory models with broad intervals and also unit root time series are explained. According to the selected method for estimating the research model, the model is explained as a dynamic, long- term and short-term model. The variables used in the research model are then checked in terms of the existence of unit root using generalized Dickey-Fuller test; the two models are estimated within the system of equations concurrent with dummy variables representing sanctions.

2. History of Sanctions against Iran

2.1. History of United Nations Sanctions

Economic sanctions are mostly known as alternative to war and coercive force. Different countries use limited economic sanctions against target countries to achieve their own political purposes, but this kind of sanctions has been generally ineffective. Diplomatic and economic sanctions have been rarely done on the part of international organizations. The community of nations which during the years between the two world wars had the ruling role in coordination of the world affairs, attempted to impose sanctions only four times that was successful only two times. Also, before sanctions against Iraq in 1990, United Nations has made a comprehensive set of sanctions only for three times. After Iraq sanctions, UN Security Council has imposed other sanctions against countries, people and groups; among those sanctions, the most important are the following ones:

Liberia (2003), Democratic Republic of the Congo (2004), terrorist groups and non- state actors (2004), Ivory Coast (2004), Sudan (2004), The suspects in the murder of Hariri (2005), Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (2006), and then Iran sanctions since 2007 [1] .

In addition to UN sanctions, countries themselves also impose sanctions against other countries unilaterally or multilaterally. US has applied these sanctions more than any other country. Just Clinton’s association made unilateral sanctions against 35 countries. These countries constituted 42 percent of the world’s population and 19 percent of the world’s exports consumers. United States itself has suffered much damage by these sanctions. According to Heritage institute estimations, economic sanctions against 42 countries have decreased United States annual exports about 19 billion dollars and have abrogated 200,000 jobs. Also, the export sector workers have lost a billion dollar of their wages.

2.2. Classifying Sanctions

Sanctions can be classified by different approaches. Here, we just mention a number of classifications.

Regarding the context of economic sanctions, sanctions are classified into two categories:

1) Trade sanctions where exports to and imports from the target country is restricted or cut off.

2) Limit or cut off financial ties.

From the perspective of sanction targets, sanctions are divided into two categories:

1) Economic sanctions with strategic purposes and,

2) Sanctions for other economic or non-strategic purposes.

Sanction for strategic purposes is often an alternative for the war option since it costs less than war and so justified for them.

In other way, sanctions are classified to economic and non-economic ones. Non- economic sanctions start before the economic ones, aimed at encouraging policy change in the target country. Non-economic sanctions are different depending on the country and the situations.

On the other hand, sanctions can also be classified according to their adopting and performing agents. Thus, sanctions can be grouped in three distinct branches:

1) Unilateral sanctions like US sanction against Iran.

2) Sanctions by some countries or unions such as the European Union sanctions against Iran.

3) Sanctions by UN Security Council like Security Council sanctions against Iran.

This latter classification can be of higher importance in terms of universality and efficiency and is more compatible with our study.

2.3. Sanctions against Iran

The greatest sanction against Iran is the nuclear ones which are provided by UN security council and binding to all countries. Besides, American and European Union’s sanctions are applied separately. In the following Tables 1-3, these three groups of sanctions are listed along with their beginning years.

3. Research Literature

Iran’s nuclear sanctions have little background. However, good academic studies have been done on the effect of sanctions on the Iranian economy in recent years; we will refer to these studies.

The effect of sanctions on Iranian economy can be of different natures. A number of experimental academic researches dealing with sanctions against Iran have tried to explore and analyze some of these effects. Now we mention these studies.

Yavari and Mohseni [2] evaluated the effects of US financial and commercial sanctions on Iranian economy in a historical study. They have tried through a statistical analysis to survey the effects of US trade and financial sanctions against Iran in 2000 on oil and non-oil exports as well as on imports of capital goods and foreign exchange facilities. The study concluded that sanctions have reduced non-oil exports and imports of capital goods, but have had no effects on oil exports. It also concluded that financial

![]()

Table 1. UN security council nuclear sanctions against Iran.

sanctions have had a greater impact on the economy and have increased lenders’ expected interest rates. The effect of the above-mentioned sanctions has been estimated through measuring Iranian consumer’s surplus as equal to 1.1 percent of the annual GDP of the country.

Aziznejad and Seyednourani [3] investigated the effects of US sanctions on Iran’s foreign trade until 2008. They have investigated the effects of sanctions on three domains of energy, goods and banking services by statistical analysis of Iran’s economy data. The study concluded that Iran’s energy sect has not been affected by sanctions until 2008. However, since 2007, the price of capital goods imported from Europe has increased 7 to 10 percent. Also, until 2008, Iranian banks had successfully managed sanctions by various techniques and good management so that they had not experienced much effect.

PourebadolahanQuichi, RahnamaiGharamaleki and Hojatkhah [4] investigated the effects of the costs of domestic research and development and capital and mediating goods imports on production in Iran’s industry and then concluded about sanctions.

Valizadeh [5] examined approaches and theories in sanctions’ effectiveness on international political economy. This study attempted to explore some new theories and approaches about the effectiveness of especially economic sanctions from an international political economy viewpoint.

![]()

Table 2. US major sanctions against Iran.

![]()

Table 3. The European union sanctions against Iran’s nuclear program.

ZiaieBigdeli, Gholami and TahmasbiBoldaji [6] investigated the effect of economic sanctions on Iran’s trade using gravity model. The main purpose of this study was to estimate the effect of economic sanctions on Iran’s bilateral trade with its 30 business partners over the period 1974-2005. The results indicate that the sanctions had negative but little effect on Iran’s trade with its business partners.

Alirezaie and RajabiTanha [7] analyzed the productivity growth of regional electricity companies, considering sanction situations and the relevant policies, by using a precise mathematical model.

Department of nation’s insurance economic studies [8] has analyzed the effects of economic sanctions on the country’s insurance industry considering the effects of inflation due to targeting of subsidies and exchange rate appreciation in the context of the possible option and cynical form. According to this study, sanctions increase the risk of the insurance industry in the country. The first immediate effect is the outgrowing of the country’s insurance market. The second indirect effect of sanctions on the insurance industry is through affecting economic growth; the reduction of economic growth in turn brings about the consequent influence on insurance industry.

Ghaffari, Jalouli, and Changi Ashtiani [9] estimated the effects of exchange rate increase and currency shocks in the framework of a macro-econometric model of small- scale structure of o the economic growth of the major sectors of Iran’s economy (1976- 2012).

Torbat [10] estimated the Impact of US’s trade and financial sanctions against Iran in a statistical investigation. The study has tried to estimate direct financial costs of these sanctions in three sections of foreign borrowing, financing oil projects, and costs of financial sanctions. These costs have been estimated for Iran to be 2.1% to 3.6% of GDP and 23.4 to 40.5 dollars per capita in 2000.

Cordesman and Burke [11] analyzed the effects of US sanctions on Iran’s military imports costs. This study also compared Iran with some other countries of the region. It shows that Iranian military imports have increased between 2003 and 2005, but in the long term, from 1993 to 2005, they have decreased.

Hakim and Rashidian [12] estimated the effects of sanctions on Tehran stock market assets and relationship with regional markets (in period of 1998 to 2009). The model for this study was estimated in GARCH method. The results show that sanctions have had a negative impact on returns of Tehran Stock Exchange market and increased capital risk of regional capital stock markets.

Thompson [13] investigated the impact of the fourth round of US sanctions against Iran in 2010. This study has shown that sanctions pressed Iran’s economy, but not enough to stop Iran’s nuclear program.

Cordesman and others [14] in a study named “American-Iranian strategic competition in the game of sanctions: energy, military control, and changing system” which is part of a long-term, multi-year review of the international strategic studies center, investigated the operations of India, Japan, Korea, Russia, China, Turkey and Persian Gulf countries in context of sanctions and evaluated the effects of sanctions on oil and gas imports along with Iran’s efforts to become self-sufficient and deal with sanctions.

Cordesman and others [15] updated the above-mentioned study in 2013 by adding more statistical data and more elaborate analysis. The report indicated that change in government authorities’ views of sanctions and the consequent switching to talks is the result of developing sanctions’ pressure and internal concerns.

Farahani and Shabani [16] have studied the effects of sanctions on Iran’s tourism. They have examined data from 2003 to 2012 using descriptive statistics (some data were until 2008). In this study, data from national, civil, family and global tourism in Iran was employed. The main finding is that sanctions did not reduce tourism and its growth. Data showed that on the contrary, in certain areas, tourism growth rate has increased.

Pour international institute [17] checked the effects of sanctions on Iran’s health and hygiene sects. This study was done via a survey questioning four subject groups of pharmacy owners, managers of drug manufacturing, drug importing and drug distributing companies including also 13 Aban Pharmacy. The findings of this study show that sanction via reduced availability of drug had an adverse effect on the Iranians health.

Cordesman et al. [18] updated the above-mentioned study in 2014 by adding more statistical data and further analysis along with a review of the chapter headings. This report pointed out some new data and issues discussing the consequences of developing pressures of sanctions, as well.

Moret [19] in a documentary analysis based on data from different documents attempted to investigate the anti-humanitarian effects of economic sanctions on Iran and Syria. He concludes that sanctions had many negative effects on humanitarian fields of these two countries. In addition to these studies, there have been done further studies concerning sanctions with different approaches which have little relevance to our review. So, we will not mention them.

As the review of literature suggests, there is no reliable research on sanctions’ effect on Iran’s economic growth so that further studies with experimental data are needed in this field.

4. Data

Variables, except for sanctions, for the period of 1977-2012 are taken from time-series data and economic indicators of the Central Bank of the Islamic Republic of Iran, yearbooks of Statistics Center of Iran and vice president of strategic planning and monitoring.

Sanction variable: A looking at Iran’s sanctions show that these sanctions are very extensive. Furthermore, sanctions have been simultaneously applied by different countries with dissimilar degrees. Hence, making these variables numeric and creating indexes for them is a very difficult task. Also, using a permanent variable as binary (0, 1) data for each sanction is difficult to the same extent. This is so because sanctions started at times close to each other and were approved and applied by three main agents that have much overlap in terms of their beginning years.

For simplicity and interoperability of inserting them into our model, we define sanction years as those years when sanctions have started and the years that followed and accordingly we assume each year that a sanction (or a set of sanctions) has started as our dummy variable so that we may pick a dummy variable for each year inserted in these three tables and allocate the zero value to years before that year and set value one for the following years. We insert each of these dummy variables separately into our model and estimate its effect. On this basis and with a look at years that these sanctions have been applied, we have 20 dummy variables for showing various sanctions; these variables will be entered into the model separately.

5. Model

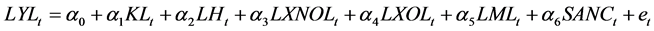

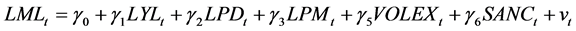

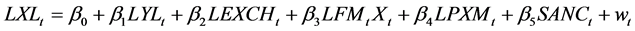

In order to analyze direct and indirect effects of sanctions on country’s economic growth, two concurrent models have been assumed; in the first model, the demand for import per capita of workers has been entered and in the second one, instead of demand for total imports, the imports of capital, intermediate and primary goods have been entered. The first model consists of three equations as follows:

(1.1)

(1.1)

(1.2)

(1.2)

(1.3)

(1.3)

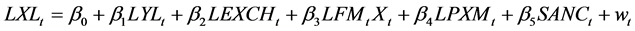

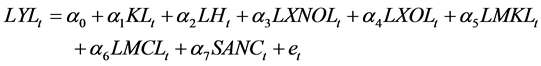

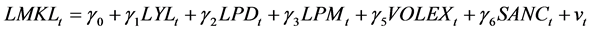

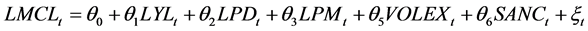

The second model is also formed by four equations as follows:

(2.1)

(2.1)

(2.2)

(2.2)

(2.3)

(2.3)

(2.4)

(2.4)

As it can be seen in the second model, Equation (2.2) is the same as Equation (1.2) so as in both models, the exogenous variables are the same and thus these equations are common to both models.

In equations of both models, we have:

LYL: The natural logarithm of GDP per capita of the labor force (working population).

LKL: The natural logarithm of physical capital per capita of workers.

LH: The natural logarithm of human capital (workers’ average years of education).

LXL: The natural logarithm of exports per capita of the employed workforce.

LML: The natural logarithm of imports per capita of the employed workforce.

LPD: The natural logarithm of the price index for domestic manufactured and consumed goods.

LPM: The natural logarithm of the price index of imported goods.

LPXM: The natural logarithm of the ratio of price index of exported goods to that of imported ones.

LPFMX: The natural logarithm of the ratio of price index of goods in foreign markets to that of Iran’s exported goods.

LEXCH: The natural logarithm of the real effective exchange rate.

VOLEX: The volatility index of the real effective exchange rate (conditional variance of LEXCH variable).

LMKL: The natural logarithm of the demand for capital goods per the employed workforce.

LMKIL: The natural logarithm of the demand for the intermediate and primary goods per the workforce employed.

SANC: a Vector containing dummy variables considered as alternative variables to sanctions imposed by the United States of America, Europe Union and the United Nations (International Security Council) on Iran.

et،vt،wt،ϑtوξt: are disturbance terms of the equations.

As shown in both equations, LYL, LXL, LML, LMKL and LMKIL are endogenous variables and other variables are exogenous.

Statistics related to research variables for the period of 1977-2012 are taken out of time-series data and economic indicators of the Central Bank of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the statistical yearbooks published by the Iran’s Statistical Center, vice-president of strategic planning and monitoring and the World Bank. The two-stage least squares (2SLS) method will be used for estimating the model of the present study.

6. Analyzing the Model and Interpreting the Results

Classical and conventional econometric methods for estimating model parameters using time-series data are based on the assumption that the variables are static. So, before doing any econometric analysis, it’s necessary to determine whether the variables are static. KPSS unit root test results in Table 4 indicate that all variables are stable. As a result, estimations carried out via these variables will have enough credibility and the obtained relationships will not be false. The results of estimating through 2SLS method, the equations of the first model of the research, are presented in Table 5 and the similar results for the second model equations estimated by the same method are presented in Table 6.

The null hypothesis of KPSS test assumes the variables’ stability and the opposite hypothesis assumes that there is a single unit root.

0, c and t represent the extended Dickey-Fuller test modes, respectively: with no intercept and time-trend, with intercept and with time trend.

It should be noted that in all equations estimated, dummy variables of SANC are entered in step-forward way for all the sanctions. Finally, dummy variable or variables which were statistically significant have been preserved in the model and the remaining ones were removed. Also, since the relations (1.2) and (1.4) in the first model are the same as relations (2.2) and (2.5) in the second model, the results of these estimations have been reported only in Table 5.

![]()

Table 4. Results of KPSS unit root test.

![]()

Table 5. Results of estimating the first model equations by 2SLS method.

*, ** and *** show the significance at the probability levels of one, five, and ten percent, respectively.

![]()

Table 6. The results of estimating the second model equations by 2SLS method.

*, ** and *** shows the probability level of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

Based on estimated results of Equation (1.1), we may say that:

By a one percent increase in the physical capital per capita of the working force, GDP per capita of that force will have a 0.539% increase.

By a one percent increase in human capital (average years of schooling of employees), GDP per capita of the labor force will increase by 0.278 percent.

By a one percent increase in the country’s exports per capita, GDP per capita of the labor will increase by 0.363 percent.

By a one percent increase in imports per capita, GDP per capita of the labor will increase by 0.094 percent.

But significant negative coefficient of 1987 sanction of US against Iran shows that after this sanction, Iran’s economic growth has been declined by 0.232 percent. This is normal because this sanction was concurrent with the year 1366 when Iran was at the height of the war , and the country’s infrastructures were damaged; on the other hand, this sanction beside restricting the export of technology to Iran, banned import of all goods and services from Iran to United States of America, too. Since at that time Iran was heavily involved in war and its exports was severely restricted and did not either have significant business relationship with the United States, it can be concluded that this negative impact much beyond indicating the effects of US sanction against Iran shows the impact of the war on the economic growth variable. As a result, it can be stated that the United States sanctions have not directly affected Iran’s economic growth.

Based on the estimated coefficients of Equation (1.2) in the first model and the Equation (2.2) in the second model, we have:

By one percent increase in the real effective exchange rate, non-oil exports of Iran per the workforce declines by 0.219 percent. This coefficient is negative due to the fact that the export industry’s dependence on importing capital, intermediate and primary goods is rooted in the very production process so that as exchange rate appreciates, the costs of importing these industries increase more than their exporting earnings and consequently, industrial production and exporting react negatively to exchange rate appreciation.

Faced with a one percent increase in GDP per capita of the employed people, the country’s non-oil exports increase by 2.274 percent.

With one-percent increase in the ratio of the price index of the goods in foreign markets to the index of export goods, the country’s exports per capita increases by 1.149 percent.

By a one-percent increase in the ratio of the exported goods’ price index to imported goods’ price index, exports per capita of the country will increase by 0.447 percent.

The negative significant coefficient of 2001 and 2004 US sanctions against Iran suggests that after these sanctions, Iran’s non-oil exports were reduced by 0.186 and 0.332 percent, respectively.

According to the coefficients of the Equation (1.3), we can state that:

By a one percent increase in GDP per capita of the employees, the demand for imports per capita increases by 1.691 percent.

With a one percent increase in produced and consumed goods inside the country, country’s demands for imports rises by 0.801 percent.

With a one percent increase in the price index of imported goods, the demand for imports decreases by 0.930 percent.

The significant negative coefficient of exchange rate fluctuation index indicates the negative effects of uncertainty in the exchange rate market on the demand per capita of imports.

But significant negative coefficient of 2009 US sanction against Iran indicates that after this sanction, Iran’s import demand faced a 0.108 percent reduction.

Coefficients of equation (2.1) for common variables are close to coefficients of equation (1.1); thus, only two new variables will be discussed here:

By a one percent increase in the imports of capital goods, the employed people’s GDP per capita increases by 0.045 percent.

By a one percent increase in the imports of intermediate and primary goods, GPD per worker will increase by 0.052 percent.

Based on coefficients of Equation (2.3), we have:

By a one percent increase in GPD per capita of the employed people, the country’s demand for imports of capital goods increases by 1.318 percent.

By a one percent increase in price index of the goods manufactured and consumed inside the country, demands for imports of capital goods increases by 0.916 percent.

By a one percent increase in price index of imported goods, the demand for capital goods imports decreases by 0.915 percent.

Exchange rate volatility index is negative. However, this effect is not significant here.

But significant negative coefficient of dummy variables of US sanction against Iran in 1979, 2001, 2006, 2007 shows that Iran’s imports demand for capital goods has been reduced.

Based on the coefficients of the Equation (2.4), we have:

By a one percent increase in GPD per capita of employees, import demands for intermediate and primary goods will increase by 1.581 percent.

By a one percent increase in the price index of country’s manufactured and consumption goods, import demands for intermediate and primary goods will increase by 1.446 percent.

By a one percent increase in the price index of imported goods, country’s demand for imported intermediate and primary goods is reduced by 1.557 percent.

The significant negative coefficient of the exchange rate variations suggests the negative effects of uncertainty in the exchange market rate on the demand value for imports of intermediate and primary goods of the country.

But significant negative coefficient of dummy variables of US sanctions against Iran in 1979 and 2009 indicates that after these sanctions, demands for imports of primary and intermediate goods has been reduced.

7. Conclusions

In this study, the direct and indirect effects of sanctions on the Iranian economy were examined with an emphasis on the external sector of the economy. In this regard, two models were developed at the same time; in the first model, total imports were considered and in the second model instead of total imports, imports of capital, intermediate and primary goods used in producing jobs have been considered, and were entered into model separately. Estimates from both models simultaneously using two-stage least squares (2 sls) method for the period 1355-1391 indicated that the sanctions has no considerable direct impact on economic growth of Iran; rather, sanctions have affected economic growth indirectly by restricting the total imports, imports of capital goods, intermediate goods, primary goods, and exports leading to slowing down of the country’s economic growth. In general, imports of capital goods were more sensitive to the issue of sanctions compared to other variables. Speaking more specifically, 2012 sanction led to a reduction in the country’s oil export revenues, 2001 and 2003 sanctions led to a reduction in export revenues, 1979 and 2009 sanctions limited the country’s imports of intermediate and primary goods, 1979, 2001, 2006, and 2007 sanctions limited the country’s imports of capital goods and 2009 sanction limited the country’s total import demand.

Also, based on the estimated coefficients of these models, it can be said that the determinants of economic growth in order of importance are physical capital per capita of the workers, exports per capita of the employees, human capital and imports per capita. Also, in exports per capita of workers, variables in order of importance are the workforce revenue per capita, the ratio of price index of export goods to that of import goods, the real effective exchange rate, and the ratio of price index of the goods of foreign markets to Iran’s export goods’ prices index.

In imports field, workers’ income per capita, the prices of import goods, the prices of domestic manufactured and consumed goods are respective determinant factors.

Also, fluctuations in exchange rates limit the demand for total imports, intermediate goods, and capital goods, but these fluctuations have not any significant effect on capital goods import.