Relative Leader-Member Exchange: A Review and Agenda for Future Research ()

Received 16 November 2015; accepted 26 December 2015; published 29 December 2015

1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, leader-member exchange (LMX) has become a mature construct in the field of organizational behavior [1] [2] . A lot of researches indicate when an employee has higher level of LMX with his or her leader, the reciprocal obligation felt by the employee will be stronger, and subsequently lead to more positive work attitude and better performance [3] -[5] . Even though the results mentioned above have been verified in many studies and have strong robustness, these studies research the influence of LMX on employees separately and neglect the fact that LMX is embedded in a broader team environment. Researching LMX without considering team environment is inadequate and incomplete [6] . In order to make up this deficiency, relative leader- member exchange (RLMX) is put forward. Next, we will introduce RLMX’s definition, distinction with related constructs, measurement method, outcome variables and future research direction.

2. The Definition of RLMX

As an extension concept of LMX, RLMX refers to actual level of one’s own LMX quality as compared with the average LMX within the team [7] . As we all know, Individuals within a team are not static and independent in their existence, they interact with each other, and one will compare his or her own LMX with other members through a series of daily interaction, informal conversation and sharing events. Hogg (2005) puts forward that LMX not only exists in the form of absolute value, but also in the form of relative value [8] . For example, when most members in a team have low level of LMX, an individual with medium level of LMX may get more extra resources, but when this individual belongs to a team with a high average LMX, the situation will not that optimistic.

3. The Distinction between RLMX and Related Constructs

Based on previous theory and empirical research results, Henderson et al. (2008) conclude that LMX can have impact on employees’ cognitive and behavior from multi-level [9] . Specifically, LMX can be divided into three levels: individual level, individual-within group level, and group level. Among the constructs we will discuss below, LMX belongs to individual level; RLMX, LMXSC, and LMXRS belong to individual-within group level; LMX differentiation belongs to group level.

3.1. LMX

LMX refers to the relationship developed by a series of interaction in leader-member dyad [10] [11] . LMX is a concept belongs to individual level. Its numerical value directly represents the quality of relationship between leader and employee. If an employee gets high score through LMX scale, it means he or she has a close relationship with the leader and belongs to “in-group” member, and because of this good relationship, this employee may occupy more leader resources and fringe benefits. At the same time, in order to giving back to leader’s special care, employees with high LMX will try their best to work hard and take part in more extra-role behaviors [12] . Thus, through LMX we can understand the relationship in leader-member dyad, but cannot get relative position of one’s LMX in a team.

3.2. LMX Differentiation

Leader will build exchange relationship with each member within a team, LMX differentiation refers to the difference degree of exchange relationships among all the dyads [13] . LMX differentiation is a concept belongs to group level, there is only one LMX differentiation value in one team. High LMX differentiation represents that LMX qualities among all the dyads vary from very high to very low and form a broad distribution range, in other words, leader form close and stable exchange relationships with some employees, meanwhile form distant and unstable relationships with some others. Conversely, low LMX differentiation represents that LMX qualities among all the dyads are similar and form a narrow distribution range, in other words, leader form similar exchange relationships with all employees within the team, no matter close or distant. Thus, through LMX differentiation we can understand the variance of LMXs, but still cannot get the relative position of one’s LMX in a team.

3.3. LMXCS

Leader-member exchange social comparison (LMXSC) refers to individual subjective comparison between his or her LMX and other team members’ LMXs [14] . The same as RLMX, LMXSC is a concept belongs to individual-within group level, but there is also some difference between these two construct. LMXCS is a subjective evaluation by individual him or herself, sample items in LMXCS scale like “I have a better relationship with my leader comparing to most members in our work team”, “when my leader cannot attend an important meeting, he or she is probably to let me attend instead”, and so on. But for RLMX, it is objectively synthesized by all team members’ LMXs, representing the actual level of one’s own LMX quality as compared with the average LMX of the team, thus only all members finish reporting their own LMX can we calculate every one’s RLMX.

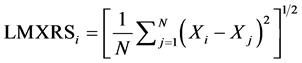

3.4. LMXRS

Leader-member exchange relational separation was raised by Harris and Kirkman in 2014. It refers to the difference degree between individual’s LMX and other team members’ LMXs. The calculate formula is showed as below. First, we get sum of squares of deviations between individual i’s LMX(Xi) and other member’s LMX(Xj); second, we get quotient of the sum of squares of deviations and the total headcount (N); third, we take arithmetic square root of the quotient above to get individual i’s LMXRS. High LMXRS means individual’s LMX is significant different from other members’ LMXs, and low LMXRS means individual’s LMX keeps consistent with others’ LMXs. Even though both LMXRS and RLMX belong to individual-within group level, some differences exist. RLMX not only contains information of difference degree, but also contains direction information, that is to say, the greater the RLMX, the larger the difference, and a positive RLMX represents individual’s LMX is higher than average LMX of the team, a negative RLMX represents individual’s LMX is lower than average LMX of team. However, LMXRS just contains information of difference degree, direction information is not included, numeric value of LMXRS cannot be negative. Both RLMX and LMXRS have their own theoretical and practical significance, researchers need to consider the matching of theoretical framework when choosing appropriate construct and proposing hypothesis. Such as RLMX is normally used in social comparison model, while LMXRS is often applied in group engagement model [15] [16] .

4. The Measurement of RLMX

4.1. Direct Synthesis Method

The calculation of RLMX is based on LMX. Direct synthesis method can be divided into three steps. First, use LMX scale to collect all team members’ LMXs; second, calculate mean of all the LMXs collected at the first step as group LMX(GLMX); third, individual’s LMX minus GLMX is individual’s RLMX [17] [18] .

4.2. Indirect Synthesis Method

Hu and Liden (2013) put forward that LMX is an individual level construct, while GLMX is a group level construct, thus synthesizing RLMX directly has certain problem [7] . They suggest using hierarchical linear model, polynomial regression and response surface analysis [19] to explore the effect of RLMX on result variables indirectly. In indirect synthesis method, RLMX is defined as the inconsistence between LMX and GLMX. When calculating the effect of RLMX on result variable, we use LMX’s regression coefficient minus GLMX’s regression coefficient to get estimated parameter, and examine significance of the parameter by hierarchical bootstrapping. In response surface analysis, slope of the incongruence line represents the effect of RLMX, when the slope is positive, representing result variable increases with RLMX increasing [20] [21] .

5. The Outcome Variables of RLMX

5.1. RLMX and Voice Behavior

As one kind of the extra-role behavior, voice behavior refers to employees point out problems and put forward constructive suggestions in order to do things better. Though voice behavior is good for organizations, it’s easy to make relationships tense because voice behavior usually challenges convention and authority. Thus, employees take some risk when they do voice behavior. Zhao (2014) conducts a research to explore the relationship between RLMX and voice behavior [22] . Result indicates a significant positive correlation. Specifically, when employees have high level RLMX, they will feel more respect from the leader, consequently lead to less sense of risk and higher sense of security when they express their own opinions and concerns. In contrast, when employees have low level RLMX, they don’t have close relationship with their leader, and feel uncertain and unworthy to express their own feeling openly and challenge status quo, consequently lead to less willingness to bear risks and less voice behavior.

5.2. RLMX and Affective Commitment

Meyer and Allen (1984) define affective commitment as positive feelings of identifying with, belonging to and participating in organization [23] . In other words, employees with strong affective commitment have strong sense of identity and belongingness, and are more willing to contribute to the organization. A large number of studies have found that work related experience, which includes perceived justice climate, employee relations, leader support, and so on, are important influence factors of affective commitment. As one aspect of work related experience, RLMX has also been proved to have positive correlation with affective commitment. A tighter affective connection with leader is conducive to increase employees’ affective commitment.

5.3. RLMX and Psychological Contract

Different from formal labor contract, psychological contract is kind of unwritten and implicit contract or expectation between employee and employer. Henderson et al. (2008) find that RLMX has significant positive correlation with psychological contract [9] . In LMX relation, leader plays a dual role: one as a partner interacted with employees, the other as symbolic representation of organization. Compared with other members’ LMXs, employee with high RLMX finds himself or herself get more resources and rewards from the leader, and tends to think the organization fully fulfill its obligations, thus psychological contract is to be satisfied. In addition, the empirical study shows individuals don’t agree that employees with high LMX contribute more than other members [24] . Therefore, low RLMX individuals won’t attribute their differential treatment to their inexertion, they are inclined to believe that organization doesn’t fulfill its obligations, thus psychological contract is not to be satisfied.

5.4. RLMX and Upward Influence

In organization, individuals will adopt some tactics to influence other people’s behaviors and attitudes, so as to achieve their purpose. These tactics are called influence tactics. Upward influence is one kind of influence tactics, refers to the influence of subordinate to the superior. Epitropaki and Martin (2013) choose RLMX and perceived organizational support(POS) as two dimensions, divide organization into resource-constrained type (low RLMX, low POS) and resource-abundant type (high RLMX, high POS), and study how individuals adopt upward influence tactic under above two different situation [25] . The result shows that in resource-abundant organization, individual motivation to use upward influence tactic declines sharply, while in resource-constrained organization, individual motivation to use upward influence tactic strengthens powerfully in order to maximize their own interest.

5.5. RLMX and Work Performance

Extensive researches have been conducted to explore the relationship between RLMX and work performance, almost all the results show a significant positive correlation between these two variables. Li et al. (2014) find individuals with high RLMX perceive their psychological contract is satisfied [26] . Based on the principles of reciprocity, they are more willing to work hard and give back to organization with excellent performance. Tse, Ashkanasy and Dasborough (2012) find individuals with high RLMX have more positive self-concept, they treat themselves as indispensable and distinctly important role in work team, and regard team’s success as their own success, therefore, they are more likely to carry out duties and pull together to achieve brilliant work performance [18] . Besides, Vidyarthi, Liden, Anand et al. (2010) and Verbrigghe (2014) further study internal mechanism of above relationship, find LMXSC and performance expectation play mediation role respectively [14] [27] .

5.6. RLMX and Self-Efficacy

According to social comparison theory, individuals with high RLMX are more likely to activate downward comparison [28] , they believe that they are better than other members within team, enjoy more attention and support from their leader, thus arise high level of self-efficacy. On the other hand, individuals with low RLMX are more likely to activate upward comparison [29] , they think they are inferior to other members in the team, obtain less attention and support from leader, thus suspect their own ability and arise low level of self-efficacy.

6. Future Research Direction of RLMX

We have introduced RLMX’s definition, measurement method and existing research results above. In the future, researchers can consider conducting researches from following directions.

First, so far RLMX mainly synthesizes by individuals’ self-evaluation of LMX. There is a problem in this measurement method: individual perception of LMX lacks unified standard, and different people will give different results when evaluating a same LMX, making the accuracy of RLMX be doubtful. Future researches are needed to explore a more accurate measurement method; for example, let immediate superior evaluate all subordinates’ LMXs, and then synthesize these LMXs to get everyone’s RLMX, etc.

Second, present researches primarily concern RLMX’s outcome variables. Few research pays attention to its antecedent variables. In the future, researchers can consider more about the influence factors of RLMX, which include leadership characteristics, individual characteristics and organization features, etc.

Third, by far the major focus of RLMX researches is its positive impact, such as voice behavior, affective commitment, psychological contract and self-efficacy. Future research may consider focusing on the negative impact of RLMX. For example, individual with high level of RLMX may be easier to induce colleagues’ envy, thus receiving more undermining behaviors, etc.

Forth, existing researches show that RLMX has a significant positive correlation with voice behavior and work performance, etc. But there is no research delving into causal relationship between them. Which variable is the cause, and which one is the effect? Whether high RLMX leads to more voice behaviors and better performance, or individuals’ active voice behaviors and brilliant performance bring high RLMS, or there is a bidirectional effect between both, deserving further research.