Deviant Realization of Foreign Vowels in the Speech-Form of Yoruba-English Nigerian Bilinguals ()

1. Introduction

A plethora of studies has established that the differences that exist in the inventories of vowels of English and Yorùbá are greater than the similarities (see Salami, 1969; Ufomata, 2004; Adeniyi et al., 2004; Bamisaye, 2007). Awoniyi (1978) identifies twelve vowels in Yorùbá and divides them into seven oral vowels, namely, [ì u e o ε ͻ a] and five phonetically realized nasal vowels, this include [ї ũ ἓ ă ]. Out of these twelve vowels that are present in Yorùbá, only three vowel sounds are common to both languages, such vowels include [u, ε, ͻ]. The implication of this is that, deviant outputs of vowels are highly ranked than faithful outputs. These faithful and deviant outputs are the major concern of this paper.

Cross-linguistic findings have shown that tongue positions are liable to changes; therefore, in English words borrowed into Yorùbá, such changes may be observed in segmental adaptation of foreign vowels.

In his study of borrowed words, Miao (2005) observes that the interface between local phonological constraints and faithfulness constraints of various segmental features produces both faithful and deviant outputs. This study only examines the deviant realization of vowels in the speech of Yorùbá-English bilinguals through phoneme mappings.

Though Steriade’s (2002) P-map proposal maintains that the perceptual exclusivity determines whether a phoneme is retained or deleted, the situation is quite different in the case of Yorùbá adaptation of English vowels. Since there is a wide gap between the inventories of vowels of the two languages, all but the three vowels which are similar to the two languages are absolutely deleted and replaced with their closest alternatives in the speech of Yorùbá-English bilinguals. In other words, Yorùbá-English speakers always rely on what they actually perceive before sourcing for the available alternative vowels that suit the purpose of their communication.

Deletion of a vowel in a donor language is therefore determined by the non-availability of the corresponding vowel in the recipient language which automatically leads to deviant realization of the vowel. Such foreign vowel is either substituted with the closest alternative or completely deleted and replaced.

The thrust of this study therefore, is to find out the phonological evidences that account for the deviant realization of foreign vowels when they are borrowed by Yorùbá-English bilinguals and to see whether this has any negative implication on the Received Pronunciation.

This study investigates the alternation of foreign vowels in Yorùbá―one of the three major languages spoken in Nigeria. It has been shown by various studies that the variability in segmental mapping is controlled by phonology so that the modified form will retain sufficient similarity with the source form. The study therefore intends to examine how Yorùbá speakers nativize foreign vowels that are incompatible with their native phonology.

This study analyzes the phonemes borrowed into standard Yoruba language from the English language. It focuses on the substitution and adaptation of vowels that are not permissible in Yoruba language.

2. Literature Review

Reports from various studies carried out on deviant realization of English vowels borrowed into local languages reveal that when foreign phonemes are processed in native phonology they manifest two possibilities; a foreign phoneme is either substituted with its closest alternative in the recipient language or it is realized as an entirely different output (cf Miao, 2005; Ojo, 2014) . The argument of these scholars is that as long as linguistic activities exist in the world, languages will continue to either make contact or crisscross and hence, modifications of phonemes cannot be underestimated whenever a foreign sound enters into a local language.

Since there is no way two languages can manifest the same inventory of sounds, the only way for them to co- exist when they contact is for the foreign phonemes to look for their alternatives in the recipient language. The results of the findings from various languages have shown that when a foreign word is phonologically processed by the recipient language, the outcome always manifests just minimal changes from its originality. For example, in phoneme substitution, which is a phonological process that takes place at the segmental level, there is manifestation of minimal modifications in the sense that foreign sounds are substituted by their closest phonemes in the inventory of the recipient language (see Silverman, 1992; Broselow, 1999; Ufomata, 2004; Kenstowicz, 2007) .

3. Methodology

The data for this study were gathered from the English words borrowed into Yorùbá, all of which are foreign lexical items introduced into Yorùbá during and after the colonial era. Furthermore, the majority of the borrowed words entered into Yorùbá language particularly for commercial purpose.

The data were drawn from Yorùbá-English bilinguals who freely mix English codes with their native language. These speakers include the artisans, businessmen and women, traders, hawkers, contractors, broadcasters, etc. Data collection includes unscheduled oral dialogues with the selected members of Yoruba speech community. Different dialogues with these selected groups were recorded on a Digital Tape Recorder (DTR) and the tapes were later played back for analyses. The dialogues that involved Yorùbá-English bilinguals who employed English loanwords in their day-to-day linguistic activities were done discreetly so as to ensure their objective participations. The data demonstrated in this study were gathered from Yorùbá speakers of English spread all over Southwestern part of

Nigeria

.

4. Findings and Discussion

In this section, the data and the analysis of data are divided into four groups, namely: substitution of foreign vowels with direct native alternatives; substitution of a foreign vowel with two different native alternatives; substitution of a foreign vowel with three different native alternatives and the vowels that motivate the choice of consonants.

Before we go further, it is expedient that we present diagrammatically these various forms of substitutions between English and Yorùbá vowels. These diagrams represent the summary of the multifarious substitutions that take place in the speech-form of Yoruba-English bilinguals. The diagrams are presented below.

Following the pattern of Chang (2009) , the diagrams below describe the various substitutions between English vowels and Yorùbá vowels.

From the diagrams (Figure 1 & Figure 2) below, it is obvious that when English vowels are adapted into Yoruba, they take on their closest alternative phonemes. In some cases, two or three monophthongs in English become one phoneme that is entirely different from the input when they are processed in Yorùbá (i.e. x3 → y). Whereas, reverse is the case with diphthongs. Some of the English diphthongs, when they are adapted into Yoruba, an input of a diphthong resulted into two different outputs of the recipient language (x → y2).

4.1. Substitution of Foreign Vowels with Direct Native Alternatives

As pointed out earlier on, the two languages (i.e. English and Yorùbá) share only three vowel sounds in common. Whenever these three vowels [u, ε, ͻ] are borrowed into Yorùbá, they preserve their lip positions. In other words, they are faithfully realized when they are processed by the recipient language. This is demonstrated in the following examples:

![]()

![]()

Figure 1. Substitution between English monophthongs and Yorùbá vowels.

![]()

Figure 2. Substitution between English diphthongs and Yorùbá vowels.

From the examples 1 - 3, the words in the first column are underlying representations [UR] of British English; those in the second column are their Yorùbá outputs, while those in the final column are the actual words in English.

It is noteworthy that the tone marks that the outputs bear do not really affect their pronunciation in Yorùbá language. This shows that even after the local phonological process(es) that might have occurred on the borrowed words, their lip positions are still maintained, hence, they are resistant to change. In this wise, this common feature adduces a strong reason the three vowels are correlated in the two languages.

4.2. Substitution of a Foreign Vowel with Two Different Native Alternatives

Some English vowels manifest differently from the vowels that are discussed above. This is because, sometimes, when these foreign vowel sounds enter into Yorùbá, they have two different alternative outputs in local phonology, depending on the word and the environment of their occurrences. This is formulated in Figure 3.

It is demonstrated in Figure 3 above that a foreign input becomes two different outputs in the recipient language. This phonological change is a common phenomenon in the speech of Yorùbá-English bilinguals in Nigeria. The following English borrowed words further confirm this assertion.

1) Monophthongs

![]()

![]()

Figure 3. A foreign input becomes two different outputs in the recipient language.

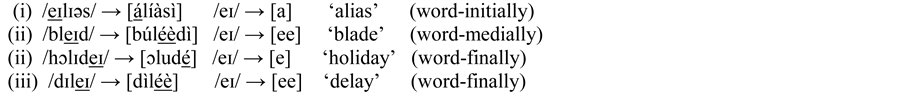

2) Diphthongs

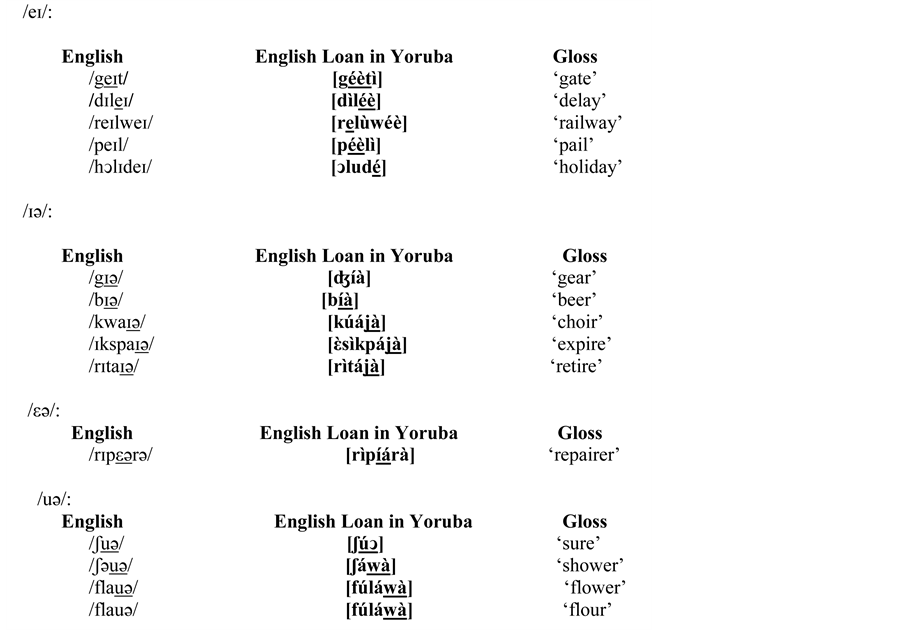

Diphthongs are sounds which consist of a glide of one vowel to another and the two vowels are realized as one. There are eight sounds in this category in English namely: /eɪ, aɪ, ͻɪ, ǝu, au, ɪǝ, eǝ, uǝ/. None of these diphthongs is present in Yorùbá language, therefore, it is predicted that a foreign diphthong will be matched to two Yorùbá phonemes that have the closest alternative features with it (Miao, 2005; Yip, 2006; Lin, 2008a; Ojo, 2014) .

The adaptation patterns observed in the data chiefly conform to the above prediction. Examples of realizations of diphthongs are demonstrated below.

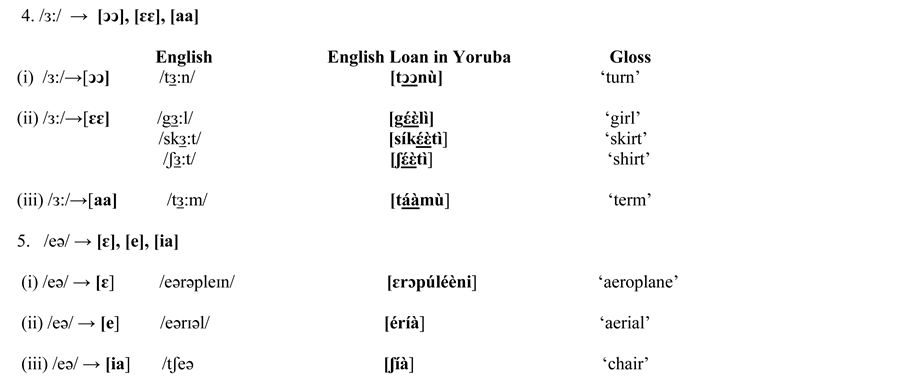

4.3. Substitution of a Foreign Vowel with Three Different Native Alternatives

Two foreign phonemes are in this category, namely, /з:/, /eǝ/. When these vowels are processed phonologically in Yorùbá, they display segmental variation in that they are sometimes substituted with three different native alternatives. This is demonstrated in the formal phonological rule formulated in Figure 4.

This rule explains that in the speech-form of Yoruba-English bilinguals, speakers always look for the closest substitutes in their language that can replace the foreign alternatives. And not only that, they also take into consideration, perceptual relationship between the foreign and local phonemes. This is demonstrated in the following examples:

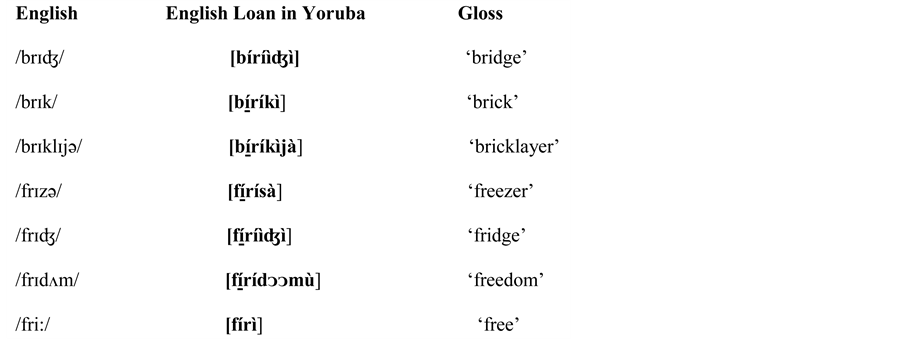

4.4. Epenthetic Vowels That Motivate the Choice of Consonants

In the adaptation of foreign words, the choice of some vowels is determined by the consonants that precede them. One of the possibilities by which foreign vowels are processed in local phonology is through consonant integration (Yip 1993; Uffmann, 2006; Lin, 2009) . This is a process by which a vowel shares the place feature of the consonant that precedes it. This is usually the pattern of foreign words when they are processed in the phonology of the recipient language. It is however observed in the data for this study that some foreign words in the speech of Yoruba-English bilinguals manifest a different pattern of vowel adaptation. Data analysis reveals a noticeable

![]()

Figure 4. A foreign input becomes three different outputs in the recipient language.

departure from the standpoint of the above scholars, which holds that the epenthetic vowel shares the place feature of the preceding consonant. This is not always so in some cases. The foreign vowel behaves differently depending upon the cluster in which it is adapted. For example, there are some borrowed words with /br/ and /fr/ clusters that do not assimilate the features of the preceding consonant; rather, they share the place features of the consonant after them. This is demonstrated below.

Again, it is important to note that apart from the two “popular” epenthetic vowels [i; u] adapted in loanword cross-linguistically, I predict that vowel [e], with the continuous influx of foreign lexical items into Yoruba, will function well as epenthetic vowel in the adaptation of English loans in Yorùbá. Though, in this study, I have limited data to justify this claim for now but as long as science and technology is prevalent in our modern society, some foreign words will unavoidably flow into Yoruba lexical items that will employ [e] as an epenthetic vowel to resolve English consonant cluster. In the data, there are two instances; they are “crayon” /kreɪͻn/ → [kereyᴐᴐnù] and “frame” /freɪm/ → [férémù].

5. Conclusion

This study shows that only three vowels are similar to the two languages―/ɛ, ͻ, u/. By implication, the inventories of vowels of both languages differ greatly from each other. This dissimilarity between the inventories of sounds of both languages advanced reasons for their deletion or substitution when they are phonologically processed in Yoruba.

It is observable in data analysis that some foreign segments which are absent in native phonology are substituted with their closest alternative phonemes. This process is common in the substitution of foreign vowels with native vowels because of the higher rate of differences that exist between the two languages.

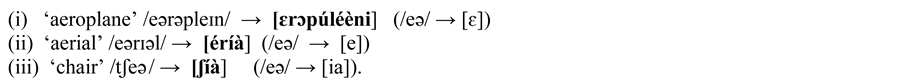

Variations in the adaptation of foreign vowels are also noticeable in the speech of Yoruba-English bilinguals. A foreign segment (vowel) can have two or more alternative outputs when it is processed in Yoruba (cf Miao, 2005) . For instance, /eə/, an English segment, can have three alternative outputs when adapted in Yoruba as follows:

Also, /eɪ/ is adapted as [a], [e], [ee] depending on the word and the position of occurrence in the following words:

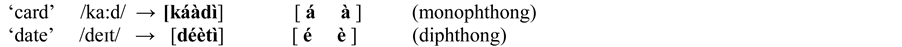

Vowel doubling is also a common occurrence in the adaptation of some English monophthongs and diphthongs (cf Ufomata, 2004) . This process seems to be operational in English words that end in closed syllables before being borrowed into Yoruba. The instances of this are shown below.

Finally, it is worthy of note that when the input segment is processed in local phonology, the output is consequential to the speaker’s perceptibility. For instance, the horizontal tongue positions (front and back) are preserved (Lin, 2009; Yip, 2002, 2006; Lin, 2007, 2008) . This simply suggests that some features of the foreign vowels are similar to the local phonemes.